Abstract

Purpose

To testthe relative effectiveness of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR) compared with a nutrition education intervention (NEP) and usual care (UC) in women with newly diagnosed early-stage breast cancer (BrCA) undergoing radiotherapy.

Methods

Datawere available from a randomized controlled trialof 172 women, 20 to 65 years old, with stage I or II BrCA. Data from women completing the 8-week MBSR program plus 3 additional sessions focuses on special needs associated with BrCA were compared to women receiving attention control NEP and UC. Follow-up was performed at 3 post-intervention points: 4 months, and 1 and 2 years. Standardized, validated self-administered questionnaires were used to assess psychosocial variables. Descriptive analyses compared women by randomization assignment. Regression analyses, incorporating both intention-to-treat and post hoc multivariable approaches, were used to control for potential confounding variables.

Results

A subset of 120 women underwent radiotherapy; 77 completed treatment prior to the study, and 40 had radiotherapy during the MBSR intervention. Women who actively received radiotherapy (art) while participating in the MBSR intervention (MBSR-art) experienced a significant (P < .05) improvement in 16 psychosocial variables compared with the NEP-art, UC-art, or both at 4 months. These included health-related, BrCA-specific quality of life and psychosocial coping, which were the primary outcomes, and secondary measures, including meaningfulness, helplessness, cognitive avoidance, depression, paranoid ideation, hostility, anxiety, global severity, anxious preoccupation, and emotional control.

Conclusions

MBSR appears to facilitate psychosocial adjustment in BrCA patients receiving radiotherapy, suggesting applicability for MBSR as adjunctive therapy in oncological practice.

Keywords: mindfulness-based stress reduction program, breast cancer, quality of life, psychosocial intervention, radiotherapy, radiation therapy

Introduction

Radiotherapy is considered to be a key component of breast cancer (BrCA) treatment, particularly for reducing tumor recurrence.1 The adverse consequences of radiotherapy are well known, including fatigue, skin toxicity, insomnia, depression, anxiety,2-5and generally poorer quality of life (QOL).6,7

Given that these issues are stress and distress provoking, a stress reduction intervention seems logical to evaluate. Stress management interventions for women with BrCA have been studied in at least 4 randomized controlled trials.8-12 These studies generally showed some decrease in anxiety and depression, with one also finding an improvement in physical function.10,11 However, these studies have been limited by one or more of the following: using a waitlist control, lack of an attention control for nonspecific therapist effects, and/or short follow-up.

Although there have been no studies of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR) for women with BrCA undergoing radiotherapy, there have been several randomized trials using yoga interventions, which is one component of MBSR13-15; guided imagery16; relaxation and imagery17; and a cognitive behavioral therapy plus hypnosis intervention.2,18Benefits were found for general health perception, physical function, QOL, and stress and depression. The studies were limited by small sample size, lack of attention control, use of a waitlist control, short follow-up, and/or use of a single nonspecific assessment measure or measurement of 1 single dimension.

We previously reported on a randomized 2-year study of 172 women with early-stage BrCA that evaluated a standard 8-week MBSR plus 3 extra sessions compared with usual care (UC) as well as a nutrition education intervention (NEP) matched for time and attention to the MBSR intervention.19 At 4 months, the MBSR group showed significant benefit over either UC or NEP on measures of anxiety, unhappiness, meaningfulness, depression, active cognitive coping, need for overcontrol, paranoid ideation, hostility, and spirituality. The study was designed to address some of the limitations of previous studies—namely, short follow-up, lack of attention control, and paucity of larger samples with a randomized controlled design.

The current article looks at the subset of women in our study undergoing radiotherapy during the course of the intervention, comparing MBSR with NEP and UC within this population of patients.

Methods

The Breast Research Initiative for Determining Effective Strategies for Coping With Breast Cancer (BRIDGES) is a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 172 women diagnosed with BrCA. Participants were enrolled from 4 practice sites: The University and Memorial Hospital Campuses of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, now named UMass Memorial Health Care, Worcester, MA; Fallon Community Health Plan, Worcester, MA; and Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI. The institutional review board of each participating institution reviewed and approved the protocol and assessment procedures, and the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School approved all recruitment and measurement procedures.

Eligibility

Women eligible to be in this study had newly diagnosed (within the previous 2 years) stage I or II cancer of the breast; were between 20 and 65 years of age; spoke English; planned to maintain residence in the study area for at least 2 years following recruitment; were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0, 1, or 2; were willing to accept randomization; and had a working home telephone on which they were willing to be contacted. Specific exclusion criteria included a previous diagnosis of cancer in the previous 5 years, except nonmelanoma skin cancer, current chronic substance abuse, and past or present psychiatric or neurological disorder.

Description of the Randomization Conditions

Once enrolled, women were randomized into 1 of 3 study conditions: MBSR, NEP, or UC. Women were block randomized by stage of disease (I or II), age (±5 years) within menopausal group, and institution. Each of the interventions was delivered at a single site.

The MBSR intervention consisted of 3 parts: (1) an introductory meeting for BRIDGES-only participants; (2) 8 weekly 2.5- to 3.5-hour sessions in groups of 25 to 30 women, with an additional 7.5-hour intensive retreat session given in the sixth week; and (3) 3 additional 2-hour sessions at monthly intervals following completion of the MBSR intervention, for the purpose of support and discussing practice issues. The MBSR was delivered by instructors with either masters’ or doctorate degrees and long-term meditation practice. The 3 additional sessions were led by a psychiatrist who had MBSR internship training and long-term meditation practice.

The NEP intervention, led by registered dieticians, was a group intervention focused on dietary change through education and group meal preparation. Practices followed the principles of social cognitive theory20-23 and patient-centered counseling.24,25 The NEP was equivalent to the MBSR in terms of contact time and homework assignments but did not contain any meditation or yoga. The UC condition received no formal intervention but was presented to women as “individual” choice, in that they could choose other activities, excluding the MBSR or NEP.

Measures

Measures were obtained on all study participants (patients with and without radiotherapy) at 4 points: recruitment into the study (baseline) and at 4 months, 12 months, and 24 months from beginning the intervention. Data were collected on demographic factors and medical history and updated quarterly.

Psychological variables were assessed using standardized and validated self-administered questionnaires. Primary outcome measures included cancer-specific QOL, as measured by the BrCA version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-B),7,19,26-28 using the overall scores and additional spirituality items, and coping mechanisms, measured by the Dealing With Illness questionnaire.19,29

Secondary measurements included the following: anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory30); depression (Beck Depression Inventory31); self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale32); resilience to stress and adversity (Sense of Coherence Scale33-35); subjective social support (Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale36); adjustment to cancer (Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale37); emotional control (Courtauld Emotional Control Scale38,39); and general psychological distress (Symptom Checklist 90–Revised40).

Statistical Methods

Outcome variables were measured on a continuous scale. χ2 Analyses for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables were conducted on all study participants to test the effectiveness of randomization. Characteristics that differed by assignment were included for adjustment in statistical models. Univariate statistics were performed on all outcomes to check for adherence to the assumptions of normality and equal variance as well as for the detection of outliers.

Because of the variation between the date of enrollment into the study (recorded as baseline) and the actual start date of the intervention, an adjusted baseline-start date was created as a calculation of the 4-month anthropometric measurement date minus 4 months. The adjusted start-of-study date was used to determine time from diagnosis to intervention initiation as well as the temporal relationship between radiotherapy and intervention initiation.

To test the hypothesis of improved measures in outcome variables with the MBSR intervention versus the control inventions for women undergoing radiotherapy during the intervention, each dependent variable (psychosocial variable) was fit using PROC MIXED for the subset of patients with a history of receiving radiotherapy while controlling for the timing of radiotherapy. Data reported are the least-squares means of the psychosocial factor scale scores generated from the mixed model. This modeling approach adjusts the error mean squared for participant dropout and imbalance caused by missing data.

Assuming 50 participants per randomization group and adjusting for the baseline level of the outcome measure (QOL from the FACT-B), there was 83% power to detect a difference of 2.5 on a 28-point scale in the functional dimension, 99% power for the social dimensions, and 92% power to detect a 7.5-point difference (on a 112-point scale) in overall QOL. Even with a smaller sample resulting from a focus on the radiotherapy subset, we still had >80% power for our primary statistical tests. It is important to note that significance testing was done without any adjustment after the fact.

Results

In all, 199 women were eligible for the study; 180 (91%) enrolled and were randomized. The analytical sample consisted of the 159 women for whom initial radiotherapy status (yes/no) was reported. Of these 159 women, 39 had no radiation therapy, and 120 women underwent radio-therapy; of the 120 women, 77 completed treatment prior to the study, and 40 had radiotherapy (art—actively received radiotherapy) during the 8-week MBSR intervention (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of study design and randomization

Baseline characteristics by intervention group for all study participants (regardless of radiotherapy status) are presented in Table 1. Participants were on average 50 (±8) years old and tended to be white, married, well-educated, and employed. Exploratory analyses of demographic and medical factors indicated adequate control from study randomization. Analysis showed no statistically significant differences between intervention groups that would influence future analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of All BRIDGES Study Participants (Regardless of Radiotherapy Status)

| Usual Care, n = 58 |

Nutritional Education, n = 52 |

Stress Reduction (MBSR), n = 53 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 15 | 26 | 13 | 25 | 9 | 17 |

| Some college | 16 | 28 | 22 | 42 | 21 | 39 |

| Bachelor's degree | 10 | 17 | 7 | 14 | 11 | 21 |

| Graduate school | 17 | 29 | 10 | 19 | 12 | 23 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 15 | 26 | 16 | 31 | 14 | 26 |

| Stable union | 43 | 74 | 35 | 69 | 39 | 74 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 56 | 97 | 48 | 92 | 51 | 96 |

| Other | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| No | 14 | 24 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 19 |

| Part-time | 10 | 17 | 10 | 19 | 14 | 26 |

| Full-time | 34 | 59 | 34 | 65 | 29 | 55 |

| Menopausal status | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 18 | 31 | 21 | 40 | 20 | 38 |

| Postmenopausal | 40 | 69 | 31 | 60 | 33 | 62 |

| Stage of disease | ||||||

| Stage I | 30 | 52 | 31 | 60 | 29 | 55 |

| Stage II | 28 | 48 | 21 | 40 | 24 | 45 |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||||||

| Positive | 34 | 65 | 35 | 76 | 37 | 82 |

| Negative | 18 | 35 | 11 | 24 | 8 | 18 |

| Tamoxifen use | ||||||

| Yes | 22 | 39 | 19 | 38 | 27 | 56 |

| No | 34 | 61 | 31 | 62 | 21 | 44 |

| Chemotherapy use | ||||||

| None | 24 | 46 | 20 | 42 | 22 | 47 |

| Before the study | 21 | 40 | 23 | 48 | 18 | 38 |

| During the study | 7 | 13 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 15 |

| Radiotherapy before study | ||||||

| None | 11 | 19 | 14 | 29 | 14 | 28 |

| Before the study | 32 | 56 | 21 | 43 | 24 | 48 |

| During the study | 14 | 25 | 14 | 29 | 12 | 24 |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||||

| 0 to 6 months | 20 | 35 | 12 | 26 | 14 | 27 |

| 7 to 12 months | 13 | 23 | 14 | 30 | 16 | 31 |

| 12+ months | 24 | 42 | 21 | 45 | 21 | 41 |

Abbreviations: BRIDGES, Breast Research Initiative for Determining Effective Strategies for Coping With Breast Cancer; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction.

Additional χ2 testing indicated adequate distribution for both radiotherapy (yes or no) as well as the timing of radio-therapy in relation to the study start date (completion of treatment before the study or undergoing treatment during the study).

Table 2 shows comparisons of major study outcomes that differ significantly (ie, P < .05) across the MBSR-art, NEP-art, and UC-art groups (ie, all women undergoing radiotherapy during the study). Data are reported as the mean score values ± standard error for the psychosocial factor scales. At 4 months, improvements in several outcome measures were shown for women in the MBSR-art group compared with women in the UC-art and NEP-art groups, notably in the following: (1) On the Dealing With Illness instrument, there was more active-behavioral coping and more active-cognitive coping for MBSR-art versus UC-art; there was less avoidance-coping for MBSR-art versus NEP-art and UC-art; (2) on the FACT, there was significant improvement on measures of emotional well-being and spirituality for MBSR-art versus NEP-art and UC-art and on social-family well-being for MBSR-art versus NEP-art; (3) on the Sense of Coherence Scale, results showed increased sense of coherence or meaning for the MBSR-art versus NEP-art and UC-art; (4) on the Mini Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale, results showed decreased helplessness in MBSR-art versus NEP-art and decreased cognitive avoidance in MBSR-art versus UC-art; (5) on the SCL-90R, there was improvement on measures of anxiety (MBSR-art vs UC-art), hostility (MBSR-art vs UC-art), the Global Severity Index (MBSR-art vs NEP-art and UC-art), depression (MBSR-art vs NEP-art), and paranoid ideation (MBSR-art vs UC-art); and (6) on the Courtauld Emotional Control Scale, there was improvement in anxious preoccupation (MBSR-art vs UC-art) and need for control (MBSR-art vs UC-art).

Table 2.

Description of Significant (P < .05) MBSR Outcomes by Intervention/Control Group Comparison for Women Receiving Radiotherapy During the Intervention Study

| 4 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DWI—Active Behavioral Coping | MBSR (63.1 ± 1.6) | MBSR (62.9 ± 1.7) | |

| UC (58.8 ± 1.5) | UC (56.6 ± 1.5) | ||

| DWI—Active Cognitive Coping | MBSR (64.8 ± 1.4) | MBSR (62.6 ± 1.4) | MBSR (62.8 ± 1.4) |

| UC (58.6 ± 1.2) | UC (58.2 ± 1.3) | NEP (57.8 ± 1.4) | |

| DWI—Avoidance Coping | MBSR (24.1 ± 1.0) | ||

| UC (26.7 ± 0.9) | |||

| NEP (28.0 ± 1.0) | |||

| FACT—Social-Family Well-Being | MBSR (22.2 ± 0.7) | ||

| NEP (19.8 ± 0.8) | |||

| FACT—Emotional Well-Being | MBSR (18.0 ± 0.4) | ||

| UC (16.9 ± 0.3) | |||

| NEP (16.7 ± 0.4) | |||

| FACT—Spirituality | MBSR (8.9 ± 0.4) | MBSR (8.9 ± 0.4) | |

| UC (7.6 ± 0.4) | NEP (7.0 ± 0.5) | ||

| NEP (6.8 ± 0.5) | |||

| SOC—Meaningfulness | MBSR (47.3 ± 1.3) | MBSR (48.1 ± 1.4) | MBSR (48.4 ± 1.3) |

| UC (43.8 ± 1.2) | NEP (44.1 ± 1.4) | UC (44.6 ± 1.2) | |

| NEP (42.8 ± 1.3) | |||

| MMAC—Helplessness | MBSR (10.1 ± 0.6) | ||

| NEP (11.7 ± 0.6) | |||

| MMAC—Cognitive Avoidance | MBSR (8.2 ± 0.4) | ||

| UC (9.4 ± 0.4) | |||

| SCL-90-R—Anxiety | MBSR (0.14 ± 0.05) | ||

| UC (0.28 ± 0.05) | |||

| SCL-90-R—Hostility | MBSR (0.12 ± 0.06) | ||

| UC (0.32 ± 0.05) | |||

| SCL-90-R—Global Severity Index | MBSR (0.22 ± 0.05) | ||

| UC (0.36 ± 0.04) | |||

| NEP (0.36 ± 0.05) | |||

| SCL-90-R—Depression | MBSR (0.31 ± 0.08) | ||

| NEP (0.58 ± 0.08) | |||

| SCL-90-R—Paranoid Ideation | MBSR (0.12 ± 0.05) | ||

| UC (0.26 ± 0.05) | |||

| CEC—Anxious Preoccupation | MBSR (14.1 ± 0.7) | MBSR (14.5 ± 0.7) | |

| UC (15.9 ± 0.6) | UC (16.4 ± 0.7) | ||

| CEC—Overall Emotional Control | MBSR (41.7 ± 1.7) | ||

| UC (46.3 ± 1.5) |

Abbreviations: MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; DWI, Dealing With Illness questionnaire29; UC, usual care; NEP, nutrition education intervention; FACT, Breast Cancer Version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-B) additional spirituality items26,41-43; SOC, Sense of Coherence Scale33-35; MMAC, Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale37; SCL-90, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised40; CEC, Courtauld Emotional Control Scale.38,39

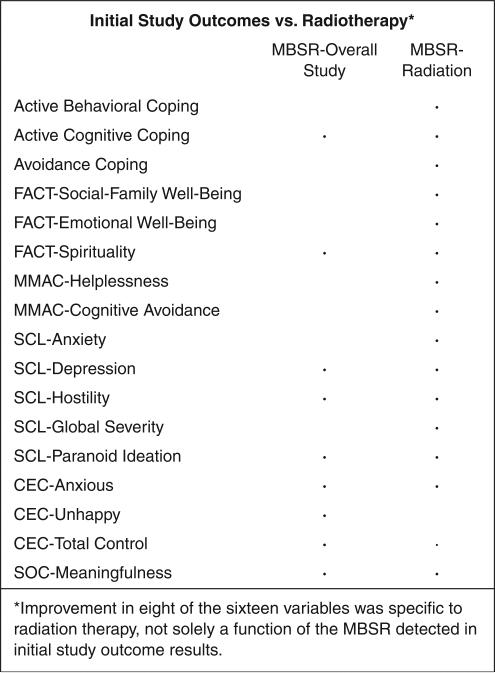

When the 16 significant MBSR-art outcome measures were compared side by side with the outcome measures of the overall BRIDGES study, improvements in 8 of the 16 variables were specific to radiotherapy (Figure 2), not solely a function of the MBSR detected in initial study outcome results (Online Resource 1). In comparison to initial study results, at 4 months, the Courtauld Emotional Control measure of unhappiness no longer showed significant improvement.

Figure 2.

Summary of Table 2: a comparison of significant psychosocial factors at 4 months, initial study outcomes versus radiotherapya

Abbreviations: MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction program; FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; MMAC, Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale; SCL, Symptom Checklist 90-Revised; CEC, Courtauld Emotional Control Scale; SOC, Sense of Coherence Scale.

aImprovement in 8 of the 16 variables was specific to radiation therapy, not solely a function of the MBSR detected in initial study outcome results.

The largest improvements in the MBSR intervention group appeared to be at 4 months (immediately following program completion), involving 16 psychosocial factors (43 factors were measured in total). At 12 months, only the following were significant: active behavioral coping, active cognitive coping, spirituality, and meaningfulness. At 24 months, significant improvement remained for 3 factors: active cognitive coping, sense of meaningfulness, and anxious preoccupation (Table 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first RCT to evaluate the specific effects of MBSR in women with BrCA undergoing radiotherapy. Results showed improvements at 4 months on 16 psychosocial factor outcomes with an MBSR program.

In the evaluation of radiotherapy patients receiving MBSR, results were consistent with previously proven MBSR reductions in cancer-related anxiety,44,45 hostility,19 paranoid ideation,19 and depression19,46; better stress management (as a measure of coping)12,47; improved emotional control19; meaningfulness of life19; and improved QOL,19,48,49especially as related to spirituality. Additional findings specific to the subset of BrCA patients receiving MBSR and radiotherapy included the following: better QOL through an enhanced sense of emotional and social-family well-being, greater coping abilities, decreased feelings of helplessness and need for avoidance, and a larger decrease in general psychological distress, including global factors. Study results did not indicate an improvement in overall levels of happiness in radiotherapy patients participating in MBSR.

Improvements in radiotherapy patients’ overall emotional QOL are similar to findings in postchemotherapy treatment studies.47,50 It is becoming more evident that stress reduction programs designed to teach mindfulness, social-emotional awareness, and deep breathing ease the side effects of treatment (eg, inability to perform usual tasks and social enjoyment of eating and recreational activities)51 and the resulting mental exhaustion52 that inhibits QOL. Also, by unlearning bad habits and applying mindfulness in daily situations, direct improvements are made in QOL while indirectly increasing chances of survival.53,54

Various studies in cancer patients,19,55,56 posttreatment patients,57,58 and fibromyalgia patients59,60 have shown that stress reduction interventions have demonstrated significant improvements in various SOC subscale variables and that practices are effective in training the patient to react by coping and responding rather than avoiding or reacting to emotions and thoughts.50 As patients focus on short-term goals and activities that are meaningful, they avoid unrealistic denial of negative outcomes.61,62 The MBSR's persistent ability to decrease the general psychological symptoms of depression and paranoid ideation, in addition to improvements in anxiety, global orientation (a stress protector that assists the individual in improving health), and mental adjustment, are encouraging. Such improved recognition and coping may be extremely useful if the patient identifies cancer as a perceived threat.

Effects were most strongly evident at the 4-month point but not maintained beyond the immediate posttreatment interval. This may be secondary to a gradual reduction in symptoms of distress over the 1-year and 2-year follow-ups, which would lead to attenuating baseline intervention effectiveness and, possibly, lower compliance levels. In addition, baseline mean levels of distress are well below any clinical cutoffs for depression and anxiety, and as has been noted,63-65 this creates a “floor” effect that makes it difficult to show significant treatment effects.

Positive aspects in the design of the study include the following: the use of 2 control groups, which minimizes nonspecific therapist effects that may be related to social support provided by program participation; a homogeneous patient population in terms of demographics, stage of cancer, and treatment modality; and a 2-year follow-up period. Our study assumes that emotional distress modifications and QOL improvements lead to improved health, and there is growing evidence that psychological factors do result in an overall improvement in health outcomes.66 The demographics of this patient population may limit the study's external validity. Finally, because the study was not designed to specifically address radiotherapy, factors such as side effects were given only minimal consideration in the study's design.

It is important to note that we did not make any adjustment to the significant tests applied to the data. At 4 months, we observed 16 of 43 tests significant at the nominal (about 37% of all tests). At 12 months, we found 4 tests significant at nominal α ≤ .05 (≈9%, or about twice that predicted by chance). At 24 months, we found 2 significant test (≈5%, or about equal to that predicted by chance). One might apply Bayesian statistics67 to assist with interpreting results. However, innovation implies being at the vanguard of the field. So, there is very little “context” in which to place the results. In the absence of established empirical data on which to fit the “priors” (ie, prior likelihood of a relationship), we concluded that it is not realistic to use a Bayesian statistical approach. Likewise, we chose not to apply some arbitrary statistical rule to adjust the level of statistical “significance.” So results are presented without any manipulation or distortion. At this juncture, any inference that a reader draws from this work will be based on the results presented in conjunction with whatever judgment he or she might wish to apply. This work will contribute context to future studies in which Bayesian statistical methods could be applied.

Conclusion

Throughout the various stages of the treatment experience, questions arise pertaining to the meaning of life as well as new strategies for coping with illness and dealing with uncertainty.68 Even though the BRIDGES study was not specifically designed for patients undergoing radiotherapy, results show that a complementary stress reduction program has potential benefits to improve QOL and decrease distress among this particular subset of patients. Because better QOL is associated with better survival rates in cancer patients,69 and stress-reduction practices pose no risk to the patient, there may be relevance to further consideration, research, and refinement of MBSR-based programs as complementary therapy in oncological practice, especially for radiotherapy patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Hébert was supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention and Control from the Cancer Training Branch of the National Cancer Institute (K05 CA136975).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Vinh-Hung V, Verschraegen C. Breast-conserving surgery with or without radiotherapy: pooled-analysis for risks of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:115–121. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery GH, Kangas M, David D, et al. Fatigue during breast cancer radiotherapy: an initial randomized study of cognitive-behavioral therapy plus hypnosis. Health Psychol. 2009;28:317–322. doi: 10.1037/a0013582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnur JB, Ouellette SC, Dilorenzo TA, Green S, Montgomery GH. A qualitative analysis of acute skin toxicity among breast cancer radiotherapy patients. Psychooncology. 2011;20:260–268. doi: 10.1002/pon.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas J, Beinhorn C, Norton D, Richardson M, Sumler S-S, Frenkel M. Managing radiation therapy side effects with complementary medicine. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:65–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg DB. Radiotherapy. In: Holland JC, editor. Psycho-oncology. 1st ed. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dow KH, Lafferty P. Quality of life, survivorship, and psychosocial adjustment of young women with breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:1555–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshields T, Tibbs T, Fan MY, Bayer L, Taylor M, Fisher E. Ending treatment: the course of emotional adjustment and quality of life among breast cancer survivors immediately following radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:1018–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0801-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, et al. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:1143–1152. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lengacher CA, Johnson-Mallard V, Post-White J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1261–1272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Post-White J, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2012;35:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro SL, Bootzin RR, Figueredo AJ, Lopez AM, Schwartz GE. The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction in the treatment of sleep disturbance in women with breast cancer: an exploratory study. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee B, Vadiraj HS, Ram A, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga program in modulating psychological stress and radiation-induced genotoxic stress in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:242–250. doi: 10.1177/1534735407306214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandwani KD, Thornton B, Perkins GH, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:43–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vadiraja HS, Rao MR, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of yoga program on quality of life and affect in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolcaba K, Fox C. The effects of guided imagery on comfort of women with early stage breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridge LR, Benson P, Pietroni PC, Priest RG. Relaxation and imagery in the treatment of breast cancer. Br Med J. 1988;297:1169–1172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6657.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnur JB, David D, Kangas M, Green S, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH. A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral therapy and hypnosis intervention on positive and negative affect during breast cancer radiotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:443–455. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson VP, Clemow L, Massion AO, Hurley TG, Druker S, Hebert JR. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life in early-stage breast cancer patients: a randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:99–109. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1738-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A. Self Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W H Freeman; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A, O'Leary A, Taylor CB, Gauthier J, Gossard D. Perceived self-efficacy and pain control: opioid and nonopioid mechanisms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:563–571. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ockene JK, Ockene IS, Quirk ME, et al. Physician training for patient-centered nutrition counseling in a lipid intervention trial. Prev Med. 1995;24:563–570. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosal MC, Ebbeling CB, Lofgren I, Ockene JK, Ockene IS, Hebert JR. Facilitating dietary change: the patient-centered counseling model. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:332–341. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cella DF. In: Manual: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Scales. Cella David F., PhD, editor. Division of Psychosocial Oncology, Rush Cancer Center; 1725 W Harrison, Chicago, IL: 1992. p. 60612. Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darga LL, Magnan M, Mood D, Hryniuk WM, DiLaura NM, Djuric Z. Quality of life as a predictor of weight loss in obese, early-stage breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:86–92. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.86-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Whyte F, et al. Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for early stage breast cancer: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:517. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39094.648553.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namir S, Wolcott DL, Fawzy FI, Alumbaugh MJ. Coping with AIDS: psychological and health implications. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1987;17:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Clin Consult Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the Sense of Coherence Scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antonovsky A. In: Pathways leading to successful coping and health. Learned Resourcefulness. Rosenbaum M, editor. Springer; New York, NY: 1990. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell D, Peplau L, Cutrona C. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminative validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson M, Greer S, Young J, Inayat Q, Burgess C, Robertson B. Development of a questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the MAC Scale. Psychol Med. 1988;18:203–209. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson M, Greer S. A Manual for the Courtauld Emotional Control Scale (CECS) Cancer Research Campaign Psychological Medicine Research Group, The Royal Marsden Hospital; Surrey, UK: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watson M, Greer S. Development of a questionnaire measure of emotional control. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R (Revised Version Manual-1) Baltimore: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cella DF, Holland JC. Methodological considerations in studying the stress-illness connection in women with breast cancer. In: Cooper C, editor. Stress and Breast Cancer. John Wiley; New York, NY: 1988. pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cella DF, Orav EJ, Kornblith AB, et al. Socioeconomic status and cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1500–1509. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.8.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) Scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, et al. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller J, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J. Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:196–197. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00025-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, Lau MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:615–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:613–622. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loizzo JJ, Peterson JC, Charlson ME, et al. The effect of a contemplative self-healing program on quality of life in women with breast and gynecologic cancers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16(3):30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Field CJ, Fairey AS. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1660–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lengacher CA, Johnson-Mallard V, Post-White J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1261–1272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osoba D, Zee B, Warr D, Latreille J, Kaizer L, Pater J. Effect of postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting on health-related quality of life: The Quality of Life and Symptom Control Committees of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s005200050078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobsen PB, Widows MR, Hann DM, Andrykowski MA, Kronish LE, Fields KK. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after bone marrow transplantation for breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:366–371. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sollner W, Maislinger S, DeVries A, Steixner E, Rumpold G, Lukas P. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients is not associated with perceived distress or poor compliance with standard treatment but with active coping behavior: a survey. Cancer. 2000;89:873–880. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000815)89:4<873::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sparber A, Bauer L, Curt G, et al. Use of complementary medicine by adult patients participating in cancer clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacon A, Caldera Y, Ronaghan C. Mindfulness, psychosocial factors and breast cancer. J Cancer Pain Symptom Palliat. 2006;2:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, Chroniak C, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mathews HL. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matousek R, Dobkin P. Weathering storms: a cohort study of how participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program benefits women after breast cancer treatment. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:62–70. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i4.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobkin P. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: what processes are at work? Comp Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weissbecker SP, I, Studts JL, Floyd AR, Dedert EA, Sephton SE. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and sense of coherence among women with fibromyalgia. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2002;9:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grossman P, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer U, Raysz A, Kesper U. Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:226–233. doi: 10.1159/000101501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carver CS, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:595–598. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vickberg SM, Bovbjerg DH, DuHamel KN, Currie V, Redd WH. Intrusive thoughts and psychological distress among breast cancer survivors: global meaning as a possible protective factor. Behav Med. 2000;25:152–160. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coyne JC, Lepore SJ, Palmer SC. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: evidence is weaker than it first looks. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:104–110. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Linden W, Satin JR. Avoidable pitfalls in behavioral medicine outcome research. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:143–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02879895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: results of two meta-analyses. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1770–1780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Distress reduction from a psychological intervention contributes to improved health for cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:953–961. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou H, Lawson B, Hebert JR, Slate EH, Hill EG. A Bayesian hierarchical modeling approach for studying the factors affecting the stage at diagnosis of prostate cancer. Stat Med. 2008;27:1468–1489. doi: 10.1002/sim.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lethborg CE, Kissane D, Burns WI, Synder R. “Cast adrift”: the experience of completing treatment among women with early stage breast cancer. J Pshychosoc Oncol. 2000;18:73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tannock IF, Ahles TA, Ganz PA, Van Dam FS. Cognitive impairment associated with chemotherapy for cancer: report of a workshop. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2233–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]