Abstract

Objectives

To review the success of barbershops as vehicles for health promotion and outline the Black Barbershop Health Outreach Program (BBHOP), a rapidly growing, replicable model for health promotion through barbershops.

Methods

BBHOP was established by clinicians in order to enhance community level awareness of and empowerment for cardiometabolic disorders such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. At coordinated events utilizing existing infrastructures as well as culturally and gender-specific health promotion, BBHOP volunteers screen for diabetes and hypertension and reinforce lifestyle recommendations for the prevention of cardiometabolic disorders from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Patrons with abnormal findings are referred to participating physicians or health care facilities. We performed a selective review of the literature in order to place this model for health promotion in the context of previous efforts in barbershops. BBHOP is among several successful programs that have sought to promote health in barbershops.

Combining a grassroots organization approach to establishing a broad-based network of volunteers and partner agencies with substantial marketing expertise and media literacy, the BBHOP has screened more than 7000 African American men in nearly 300 barbershops from more than 20 cities across 6 states.

Conclusions

The BBHOP is an effective method for community level health promotion and referral for cardio-metabolic diseases, especially for AA men, one of the nation’s most vulnerable populations.

Keywords: research, African Americans, men’s health

African American men are diagnosed later and die more often from a variety of diseases compared to women and other racial/ethnic groups. These disparities have been acknowledged and well documented within the research literature.1 Emerging studies have even begun to elucidate the reasons for these disparities, including significant barriers to awareness and screening.2 Low priority of health concerns, limited time, poor information/lack of knowledge, perception of treatment as experimental, negative beliefs and mistrust of the health care system, geographic isolation, and cultural insensitivity among many providers have all been implicated in moderating the health-seeking behavior among African American men.3,4 These studies have also demonstrated that educational interventions can significantly enhance improved attitude towards and participation in screening efforts.4,5

The lead author, an independent podiatric surgeon practicing in a predominantly African American area of Los Angeles, California, was motivated to found the Diabetic Amputation Prevention (DAP) Foundation after seeing a continuous influx of patients suffering from podiatric complications of diabetes over the last 20 years—diabetic ulcers, serial amputations, and neuropathic pain. The mission of the DAP Foundation is to increase public awareness of diabetes through culturally specific education, research and community-based programs. Its main goals are to empower the African American community to better understand the disease, its complications as well as the standard of care as it relates to diabetes and its management. Additionally, DAP aims to decrease the amputation rate among high-risk populations both domestically and internationally through providing preventive education, early intervention, state-of-the-art technologies, and applying a multi-disciplinary approach to managing the disease process. Recognizing the importance of engaging communities directly, the Black Barbershop Health Outreach Program (BBHOP), was designed as a national program to address African American men at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes through a combination of screening, education, empowerment, and community capacity-building activities.

In this paper, we explain the rationale for placing health promotion activities in barbershops, examine prior work in the area of barbershop outreach, describe the BBHOP model for health promotion using barbershop outreach, detail the key steps for implementation, and discuss efforts to integrate research into BBHOP.

RATIONALE FOR PLACING HEALTH PROMOTION ACTIVITIES IN BARBERSHOP AND PRIOR WORK IN THE AREA OF BARBERSHOP OUTREACH

Community Outreach and Health Promotion—“Going to the Barbershop”

Recognizing the need to introduce health information in a context that would be both culturally appropriate and trustworthy, health care advocates have traditionally approached churches, community centers, fairs, and other community-based organizations, including beauty salons.6–8 Disseminating health information in this context has paid valuable dividends, but predominantly for African American women and children.

Since the mid 1980s, innovators, such as Eric Whitaker,9 Simons and colleagues,10 Kong and Saunders,11 and others have postulated that barbershops, through their established credibility as forums for indepth discussions, information gathering, and the relaying of shared experiences, provided an opportune venue for health outreach to African American men, a traditionally marginalized population.11–19 Emerging evidence strongly suggests that effectively reaching African American men in medically underserved urban communities in order to influence health-seeking behaviors requires a “bottom-up, community-centered approach, through institutions well accepted within their neighborhoods that can provide culturally credible information.”10 Barbershops are ideally situated to play that role.

In 1986, Kong included barbershops among a consortium of community partners focused on combating the epidemic of undiagnosed hypertension after realizing that outreach efforts in traditional settings were not reaching African American men.11 Eric Whitaker, as founder and director of Project Brotherhood in Chicago, Illinois, merged clinical care with barbershops—bringing medical care to African American men in a trusted environment where they already invest time. Virgil Simons was motivated by the devastatingly disparate toll prostate cancer exacted on African American men to begin raising awareness in barbershops. His efforts begat Prostate Net, an organization started in 1996, which by 2004 began partnering with medical centers serving largely minority communities. Prostate Net trained barbers as lay health educators and peer navigators for African American men. Based in New York, the Prostate Net Barbershop Initiative currently provides culturally appropriate information to African American men in barbershops through interactive, computerized kiosks in more than 20 locations across 6 states.

Concurrently, formative work has evaluated the possibility of performing community-based participatory research (CBPR) in barbershops collaboratively with academic institutions.14,15 TRIM (Trimming Risk in Men) Project out of University of North Carolina, through a CBPR approach, has conducted pilot work suggesting the potential for health promotion in barbershops. Recent barbershop outreach initiatives have tried both to integrate novel technology, data collection, and research designs into educational and screening efforts for a variety of diseases. Cowart et al used trained nurses to provide educational sessions in barbershops using CBPR approaches.12 The Connecticut Cancer Partnership program, Reaching Urban African American Men with Prostate Screening Information, run by Andrew Salner, increased rates of screening by using barbershop outreach to identify cultural barriers to prostate screening among West Indian men in Hartford through barbershop outreach. Using a pre- to postintervention design, Hess et al trained barbers as recruiters and health educators to screen men for hypertension and deliver health promotion messages.16 Similar to Hess et al, Cheryl Holt, at the University of Maryland through the Barbershop Men’s Health Project conducted in Birmingham, Alabama, introduced an experimental design to promote prostate and colorectal cancer awareness.17 This study randomized barbershops to either a cancer-specific informed-decision aid or control group exposed to cardiovascular disease information only. The Office of Cancer Control and Prevention in New Jersey has leveraged its statewide cancer prevention infrastructure to educate men in barbershops statewide about prostate cancer by partnering with Prostate Net as well as evaluating its effectiveness.18 In each of these studies, the researchers relied on barbers to become trained lay health educators or liaisons. Accounts of the sustainability of this method—using barbers—have been questioned by even the investigators themselves. Moreover, there is concern over how to build long-term relationships between barbers and health care providers given the nature of small businesses in already economically tenuous communities and distrust of the medical profession among racial/ethnic minority populations.20 The barbershop appears to be an ideal outreach location, but whether it is the appropriate vehicle to disseminate health information and secure appropriate chronic medical care in a reliable, sustainable manner, remains unsettled.21

The idea to utilize the existing community infrastructure of African American–owned barbershops at a national level has not previously been described. The concept of a national approach originated with a discussion between the lead author and his own barber. After confirmation through consultation with colleagues that this may be an acceptable venue to disseminate and promote health messages, an informal and expanded one-on-one dialogue with local barbers around Los Angeles then took place. Personal accounts of being affected by complications of CVD further cemented the notion that barbershops would be excellent partners in community health outreach. Most, if not all, of the barbers could recall a patron, family member or fellow barber having a heart attack, stroke, or amputation. The community input into the design of the program was critical to informing a prudent strategy for both local and national implementation.

BARBERSHOP-BASED HEALTH PROMOTION CONCEPTUAL MODEL

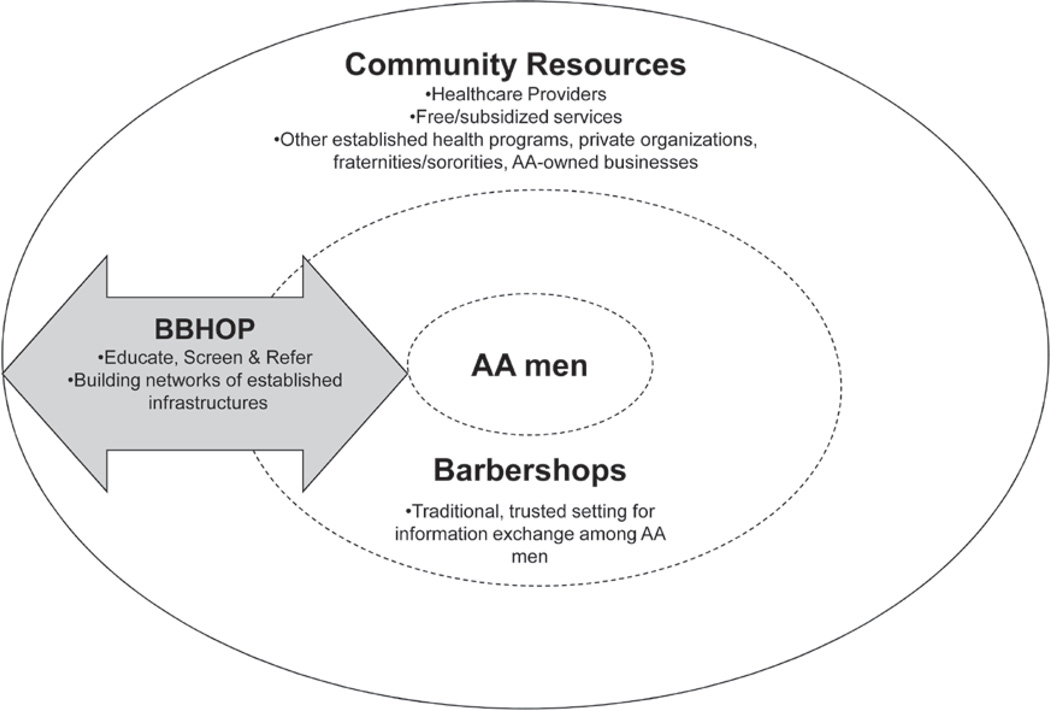

The BBHOP model for health promotion in barbershops addresses both individual-level factors such as self-empowerment skills and health literacy as well as community-level factors such as popular figure-based role modeling22 media campaigns, and political advocacy. Behavioral theorists tend to focus explanatory models of behavior change on either individual or community-level factors. Consequently, interventions often are similarly targeted to a single level of influence. The advantage of the engagement framework adopted by BBHOP rests on its multifaceted, multilevel approach, consistent with the more recent social ecological models of behavior change23,24 and social marketing frameworks.25,26 BBHOP nests culture- and gender-specific strategies addressing individual African American men at barbershops within a broader (nationwide) network that mobilizes volunteers, nurses, health workers, and community members (Figure 1). For example, the model incorporates a captive audience strategy that melds social support and interaction with peer pressure to better penetrate the patron population.27,28 By increasing awareness and connecting African American men with previously untapped health resources through barbershops, BBHOP aims to empower both individuals and communities to work toward health improvement. Simultaneously, it aims to create new leaders in community health and enhances community capacity to address key public health issues.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Barbershop-Based Community Engagement and Health Promotion

Abbreviations: AA, African Americans; BBHOP, Black Barbershop Health Outreach Program.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BBHOP MODEL FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

Outreach Objectives

BBHOP is designed to educate, screen and refer patrons in barbershops nationwide for needed care related to diabetes and hypertension. To do so, BBHOP develops and evaluates culturally sensitive and appropriate educational material in order to educate the African American community about diabetes and hypertension. BBHOP conducts barbershop-based screening with coordinated referrals targeting persons with undiagnosed hypertension and diabetes in order to institute early intervention. Through self-administered surveys, BBHOP also strives to identify behavior, social, and economic barriers that prevent African Americans from adopting healthier lifestyles, which is critical in order to effectively implement successful community programs.

Outreach Sites

Barbershop recruitment

All BBHOP participating barbershops are African American owned. BBHOP begins recruitment by identifying area barbershops using an internal database created from client lists of barber/hair product companies, state regulatory lists, and yellow/white pages of licensed barbers, BBHOP Web site activity, informal suggestions from member barbershops, and enrollment into our network from barbers who visit our Web site (http://www.blackbarber-shop.org). Dedicated staff, some of which are former barbers themselves, then make contact with prospective barbershops, speaking in person to management staff and associate barbers to gauge interest. Barbers are shown a video describing the program. Next, staff evaluates barbershops using formal criteria, including: number of barbers, barbershop size (estimated square footage), accessibility, visibility, cleanliness, safety, longevity, and cooperativeness. The configuration of barbershops will vary significantly. However, the ideal available space to be effective in the screening process is approximately 10 × 10 ft. This will accommodate an 8-ft table and about 3 chairs. Access of the establishment to those who are not familiar with the location is very important. BBHOP selects locations, whenever possible, that promote barbershop patrons and causal observers to participate. Other facility characteristics such as electricity, cleanliness, restroom availability, and parking are important considerations used to determine inclusion in the network. Upon selection, barbers are asked to complete a sign-up form providing permission and signifying enthusiastic support for health promotion in their barbershops on the outreach day. Above all else, barbers serve to encourage participation of patrons in the screening process and reinforce health messages delivered by the volunteers; therefore, staff who are engaged understand the importance of being cordial and accommodating as essential elements to successful barbershop-based health promotion. BBHOP reinforces and rewards their participation with branded t-shirts, capes and donated hair care products. No financial incentives are given; however, participating shops are promoted during community-wide recruitment (e., on radio ads, Web site, etc).

Volunteer recruitment and training

Each barbershop has volunteers that fulfill 3 roles: team leader (TL), medical volunteer (MV), and community health volunteer (CHV). TL is responsible for all activity at each barbershop. TL maintains logistical organization and communication among several barbershops. The TL organizes all personnel at each location. Specifically, TL attends all training and orientation, sets up at designated location per protocol, corresponds with barbershop contact about all aspects of screening effort, and ensures that all materials needed for screenings are on location. The TL is also responsible for: corresponding with media and/or political visitors; promptly reporting any incident by using the provided incident form, and collecting all completed survey forms at the end of the day.

For each barbershop, BBHOP recruits 2-person teams of volunteers consisting of a medically trained personnel (MV) and lay community volunteer (CHV). The MV may be 1 of the following: (1) registered nurse, (2) physician, (3) paramedic/firefighter, (4) PA or medical student under supervision. The MV is responsible for taking and interpreting blood pressure and blood glucose tests, keeping screening area clean and clear of debris at all times, discussing abnormal findings with participants, and attending training/orientation. In some instances, high-volume shops may require up to 2 MVs. CHVs assist MVs while obtaining informed consent, disseminating health information, answering questions posed by patrons, administering surveys, and serving as a liaison between barbers and core event organizers. CHVs and MVs are trained to reinforce lifestyle recommendations for the prevention of cardiometabolic disorders from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.29

Volunteer recruitment begin weeks in advance of the event using established organizational partnerships with health professional organizations, fraternities/sororities, academic institutions as well as local and national community-based organizations. Recruitment strategies range from formal partnerships with national organizations that facilitate participation of local chapters, enlisting organizational leadership to adopt local events and recruiting members to serve as primary volunteers at select barbershops, and directing e-mail blasts to organizational e-mail lists to solicit individual volunteer participation. Volunteer recruitment materials simply explain the mission, objectives, and basic duties ascribed to participants at each event. BBHOP core staff disseminates materials through visually appealing e-mails, flyers, and posters.

Based on a written training notebook, BBHOP conducts volunteer orientation and training for the MV and CHV during the 2 weeks prior to each event. At sessions organized based on group affiliations (eg, sororities, student organizations, etc) and at convenient, low-cost locations, BBHOP staff orient to the barbershop protocol and review roles. BBHOP staff provides intensive training for the MV conducting the blood pressure measurement using an automated blood pressure monitor and blood glucose testing with a glucometer. CHVs review health informational materials, practice consent procedures, go through survey forms, role play potential barbershop-based problem solving, and address frequently asked questions in the barbershop.

For TLs, BBHOP staff schedule regular contact through telephone calls, personal visits, and roundtable discussions where a process is established for prompt response to issues, questions, and concerns raised by TLs. Core staff continuously evaluate and provide feedback to TLs regarding organization and preparedness for the outreach event. After events, volunteers are recognized for their efforts through socials and certificates of appreciation.

Identifying local referral providers

Primary care providers are identified through “medical anchors” in the local community—large multigroup practices, health systems, and medical schools. Through these partnerships, willing providers are identified who will receive patrons referred from the barbershop with abnormal findings by MVs in the barbershop. BBHOP specifically targets federally qualified health centers, free clinics, and providers willing to see low-income adults through sliding-scale payments. For patients who have urgent care needs, MVs direct those patrons to emergency services such as a local emergency room. Relationships with local fire departments and EMTs have facilitated our access to efficient transfer of these patrons when the need arises.

Outreach Participants

BBHOP recruits African American men in barbershops by: (1) soliciting participation from regular patrons and (2) promoting events in advance of the outreach day in order to encourage men to visit local barbershops. In the weeks preceding an event, BBHOP arranges television and radio public service announcements including national and local celebrities, and disperses flyers, postcards, and posters using local community members called “street teams.” On the day of the event, BBHOP conducts panel discussions on morning radio shows with complementary target demographics. In the barbershop, volunteers and barbers encourage all individuals, irrespective of their reason for being in the barbershop, to receive health information and screening. Community volunteers then obtain consent from patrons for screening and survey completion. Those participants found to have abnormal findings are counseled by medically trained volunteers, provided with contact information for participating providers and referred for care.

Promotion planning, timing, and city selection

Three to 6 months in advance, BBHOP staff selects target cities and timing of outreach efforts based on demographics and ongoing local events (eg, sporting, cultural, or health events). Staff members develop relationships with a diverse group of local community partners. These organizational partners assist with the planning, implementation, and evaluation of each event and typically include academic institutions, local departments of health, community-based organizations, health care professional organizations, and individual providers. Community-specific media promotions, including those that are radio, print, and Internet based, begin 4 to 6 weeks prior to the event and intensify as the outreach day approaches.

Outreach Design

Using a small cadre of committed staff, BBHOP coordinates health promotional events within barbershops using teams of medically trained and lay volunteers from the local community. Proceeded by months of planning, promotion, and volunteer training, BBHOP targets dozens of barbershops, recruits scored of volunteers, and reaches hundreds of African American men in single-day events. Conducted on Saturdays in target cities, teams of 2 (1 MV and 1 CHV) volunteers measure provide health education, cardiovascular screenings, and administer surveys in the barbershop. Medically trained volunteers then interpret results and refer patrons with abnormal findings to participating physicians or health care facilities.

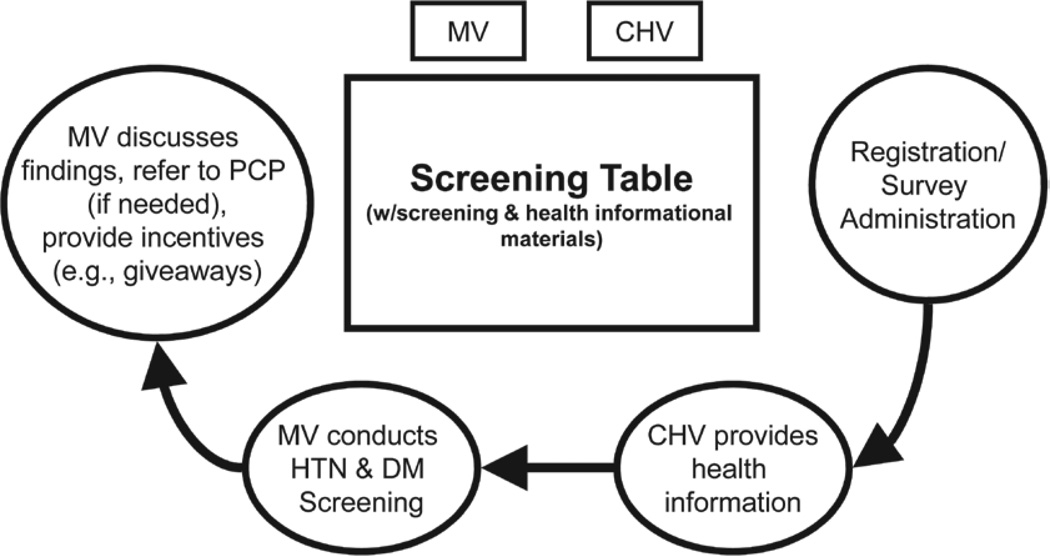

Protocol for barbershops

Each patron who enters the barbershops on the day of events is approached by a CHV, who offers health information and screening for hypertension and diabetes (Figure 2). CHVs then obtain consent, discuss health implication of diabetes and hypertension while providing BBHOP-developed written materials information, and administer a brief survey. MVs then perform and interpret blood pressure and glucose testing. MVs record clinical test results on the survey form and give results to the patron on a referral card. When necessary, patrons found to have abnormal test results are referred to local health care providers for follow-up. Finally, CVHs give each patron a branded bag containing a BBHOP t-shirt, health informational materials, and give-aways (eg, health food samples, etc) as incentives for participating.

Figure 2.

Overview of Barbershop-based Outreach Protocol

Abbreviations: CHV, community health volunteer; DM, diabetes (blood glucose testing using a glucometer); HTN, hypertension; MV, medical volunteer; PCP, primary care physician.

Outreach Measures

Blood pressure and blood glucose

All blood pressure readings are measured in the barbershops with an automated, electronic monitor using an appropriately sized arm cuff with the participant seated comfortably in a chair. All blood glucose measurements are taken using a random finger stick of blood and readings determined using a standard lancet, strip, and glucometer. When possible, rates of screening are determined as a proportion of total number of patrons attending the barbershop during the outreach day.

Survey instrument

During the barbershop screening, CHV assist patrons in completing a brief, written self-administered survey form. Each form solicits information about various factors that might influence cardiovascular health. These include demographic characteristics, health care access and utilization, smoking history, eating behaviors, physical activity, and perceived health. Portions of the instrument (eg, demographics, smoking history, and perceived health) are adapted from items used in California Health Interview Survey and Los Angeles County Health Survey with modifications informed by field experience, outreach staff and partners.

Outreach Materials

BBHOP provides a tool kit to participants containing health information and illustrations explaining population-specific epidemiological data, diagnosis, treatment, and complications resultant from poor care management. Information contained in the BBHOP tool kit is derived from publicly available patient information materials created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This authoritative information is then adapted for an exclusively African American male audience with accompanying race/ethnicity-specific data, language, and illustrations.

Recruitment in Target Cities

BBHOP has recruited 289 barbershops in 19 cities across 6 states representing 4 US regions (west, northeast, midwest, and south). More than 400 nurses, students, and other volunteers supplied by a national nursing organization; 2 African American fraternities and sororities, 8 local universities, 5 health care organizations, and several individual clinicians and government agencies provided in-kind donations of staff time and/or data collection supplies. BBHOP has shown success in its national media outreach efforts featured on television (eg, The View, NBC Nightly News) and in print (eg, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, etc). Live broadcast media coverage was provided in Los Angeles by KJLH, an African American–owned radio station. A local television station in Georgia, Fox News Atlanta, covered barbershop-based screenings held there.

Qualitatively, study participants were fairly representative of barbershop patrons. Public health graduate student volunteers observed fewer than 20% of Los Angeles patrons declining to complete the study enrollment survey after the aims and process had been explained. Notably, the barbers themselves played a major role in facilitating participation. The rate-limiting step was the efficiency of the operation in moving men from one station to the next and the numbers of trained health professionals available to perform screening procedures and collect data.

BBHOP has targeted urban communities with predominantly African American populations in New York, Missouri, Louisiana, Georgia, and California. Los Angeles, California; Chicago, Illinois; St Louis, Missouri; New Orleans, Louisiana; Atlanta, GA; and Harlem, New York (which held BBHOP’s largest health outreach to date) represent some of the most vulnerable and densely populated African American communities in the nation. For instance, in New Orleans, where 67% of the population is African American and 27% live below the poverty level, 1 in 3 residents self-report having had no exercise in the past month and are considered obese, while 1 in 10 have been diagnosed with diabetes.30,31 These communities also have some of the highest rates of uncontrolled or undiagnosed hypertension and resultant disease-related complications.32

To date, more than 7000 African American men have been screened in 6 states to date (Table). In California, where coordinated outreach efforts occurred in 7 cities simultaneously on one day, we recruited 86 barbershops and screened 1722 African American men. On a single screening day in Chicago, 30 participating barbershops reached 698 African American men. On many occasions, screened patrons required immediate medical attention in an emergency department, which underscores the severity of health-related deprivation among African American men. For example, among the 200 African American men screened in New Orleans, nearly 5% were referred to the emergency room for uncontrolled hypertension.

Table.

Black Barbershop Health Outreach Program Screening Across 6 States

| State | City | Participating Barbershops (n) |

Partner Organizationsa | Volunteersb (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | Los Angeles (county) Sacramento, Oakland, Vallejo, Long Beach, Inland, Empire, Fresno | 96 | Charles Drew University, UCLA, American Heart Association, Los Angeles City Government | 192 |

| Illinois | Chicago | 30 | University of Illinois-Chicago, State of Illinois Department of Health and Human Services | 60 |

| New York | Harlem | 50 | Medgar Evers College, Bronx Health Outreach Program, CUNY | 100 |

| Georgia | Atlanta | 25 | Morehouse School of Medicine, School of Nursing, Alpha Kappa Alpha | 50 |

| Louisiana | New Orleans, Alexandria, Baton Rouge, Rustin, Grambling Shreveport, Lafayette | 70 | Xavier, Louisiana State, Tulane University, Alpha Phi Alpha, National Conference of Black Mayors, St Francis Medical Centers, Rapides Resource Center, National Baptist Laymens Movement, Southern University-Baton Rouge | 138 |

| Missouri | St Louis, Kansas City | 48 | Swope Medical, Swope Health Services, Myrtle Hilliard, Comprehensive Health Center, Black Health Coalition, Mark Twain Community Resource Center, Public Health Department, Truman Medical Center | 96 |

| Total | 319 | 636 |

Abbott, Legends of Basketball, California Legislative Black Caucus, WeConnect Foundation, and CalQuits have provided intermittent and/or continuous support in the various cites where screening has occurred.

Included are officially registered and trained—additional volunteers often spontaneously participate and aid in logistics of performing onsite outreach.

EFFORTS TO INTEGRATE RESEARCH INTO BBHOP

Data Analysis and Program Evaluation

The primary aim for data collected is identify African American men at risk for diabetes and hypertension and to determine rates of screening. Secondarily, data collected through the self-administered survey serve to evaluate the population served through barbershop-based health promotion by obtaining demographic, clinical, and health behavioral data. These data will be used to develop a baseline description of the various regions reached through this type of outreach effort. Descriptive analyses will be performed comparing characteristics of this barbershop-based population to that of well-established population-based samples of African American men (eg, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, etc) to gauge the potential for barbershop-based intervention pilot studies.

Each outreach effort is assessed via a postevent focus group conducted by core BBHOP staff. During this debriefing, representatives from the various organizational partners, barbers, patrons, and volunteers provide feedback from the event. BBHOP staff consolidate qualitative feedback into themed areas for continuous program quality improvement (eg, inadequate supply delivery, confusion with survey administration, criticisms of training, barbershop site problems, etc).

DISCUSSION

This program seeks to address cardiovascular health of African American men using a novel approach—going to the barbershop to provide health information, services, and referrals. It does so nationwide, reaching more than 7000 African American men across 6 states by building upon established, trusted, network, organizational, and institutional partners. BBHOP is able to leverage the successes and experiences of its partners to increase the scope and feasibility of outreach efforts.33 Funding for outreach efforts by community-based organizations is scarce. This collaborative approach allows BBHOP to be nimble, adaptable, and flexible to the various environments into which it tours.

As has been suggested by others,10,12,14–19,34 the barbershop can provide an effective environment for outreach. But the sustainability of those outreach efforts must be tempered with the realization that the barbershop is business first and health promotion a secondary goal for the proprietors (Yancey, in press, 2009;256). Interventions, therefore, must be simple: inform, screen, and refer in a seamless and relatively transparent manner. The strategies must be targeted to and add value for the barbers. Including barbershops on promotion materials, providing work materials with BBHOP logos, and increasing business on the day of screening all nurture a symbiotic relationship with participating sites so that health is infused into the barbershop setting.

Beyond the barbershop, investment in developing human capital and community empowerment is a critical element of BBHOP. Operationally, BBHOP is supported by men and women from the communities it reaches. Community outreach workers are hired with specified responsibilities. Volunteerism is an important component of any outreach effort; however, paid and well-trained workers are crucial to seamless operation. BBHOP has embraced the need for better marketing of health messages paying particular attention to graphic design, image, and branding by engaging individual community members and established organizations in the development of these materials. BBHOP solicits local neighborhood businesses to provide services, materials, expertise, or other in-kind contributions that may provide a foundation for long-term relationships. The project also patronizes local African American merchants (eg, t-shirt and other promotional material purchases), exemplifying the grassroots nature of this health outreach. Local media plays a strong role in the success of BBHOP initiatives. Media outlets with predominately African American audiences provide particularly valuable venues for promoting upcoming events. By embracing local businesses (often African American owned), what may be lost with respect to scale is gained with regard to dedication to cause, recognition of community assets, and commitment to community values.

Challenges

Volunteer mobilization

Reproducing the magnitude of volunteer effort in the various cities where outreach is performed can be difficult. The areas in which the greatest disparities exist are often the same areas in which the volunteer effort is the most difficult to mobilize. For example, in Louisiana, while volunteer outreach in New Orleans was overwhelming, getting medically trained volunteers to rural areas is often more difficult. In order to overcome these resource distributional challenges, BBHOP centrally reallocates volunteers from other areas ensuring an adequate distribution of both medical and nonmedical volunteers weeks prior to but as late as the day of events. When coordinating hundreds of volunteers on a singles day, TLs can play a pivot role in ensuring volunteers arrive at locations, addressing late or absentee barbers, and redirect resources and patrons to nearby barbershops when problems arise.

Securing buy-in from key stakeholders

When politicians and community leaders have a vested interest in issues related to African Americans, gaining support both in deeds and resources is straightforward. However, not all community leaders understand or have a stake in the health of African American men. When there is a lack of ethnic representation in key leadership positions, outreach efforts to these groups are often limited. Under these circumstances, resources have gone disproportionately toward raising awareness among leadership as opposed to promoting health in the community. This highlights the importance of diversity among health professionals, politicians, educators, and community leaders in order to have experiential empathy for health disparities. For example, in some communities, leaders have been resistant to endorse a program that appears to target exclusively African American men. In meeting this challenge, BBHOP develops relationships with local community leaders in advance of outreach efforts providing evidence of the health disparities in their local communities and engaging them as ambassadors for the program. Through their support, resistant stakeholders can be better persuaded by community members who have been on the ground in these target communities compared to an “outside” organization.

Sustainability and funding

As with other community-based efforts built upon a patchwork of philanthropy, research grants, and in-kind donations, BBHOP works tirelessly to seek out new funding opportunities to bring resources. While BBHOP initially relied on intervention-focused industry, foundational, and local governmental support, it now, through its academic partnerships aimed at CBPR, is able to compete for research grants through the CDC and National Institutes of Health. A nationwide effort, it remains a challenge to continue building an infrastructure that provides health promotion, maintain a relationship with an ever-changing clinical network, and perform substantive research to inform its own work as well as the work of others in the African American community. However, as national health care reform is being implemented, there will hopefully be new sustainable business models for community-level interventions such as BBHOP that build community capacity for health promotion and disease prevention, ultimately improving health outcomes and reducing hospitalizations as well as premature deaths. Strategies include, but are not limited to, partnering with health maintenance organizations and county health departments to become education resources, retention follow-up reminder sites in exchange for direct or indirect support (eg, black barbershop health insurance program).

Next Steps: Conducting Formal Community-based Participatory Research

BBHOP’s ambitious goal is to screen 500 000 African American men by 2012. BBHOP is also embarking on a campaign to integrate rigorous CBPR into its outreach efforts. Through partnerships with academic institutions and clinicians, BBHOP plans to evaluate various channels of information aimed at aiding African American men in understanding cardiovascular disease. In doing so, we endeavor to introduce scientifically rigorous research methodologies in the form of quasi-experimental designs embedded in culturally appropriate approaches to supplement our ongoing data collection. Nonetheless, research designs must be balanced against outreach goals. The extent to which bureaucratic hurdles of academic progress slows community action needs to be actively moderated. Continually reassessing stated goals and objectives from both perspectives can minimize divergence from intended outcomes.36 Fundamentally, the 2—outreach and research—can be complementary. In fact, outreach plus research (or evaluation) catalyzes progress.

This model for community engagement has the potential to be an effective and innovative means to conduct health promotion and research in minority communities across not only cardiovascular disease but also a variety of other conditions and within other venues. Utilizing the existing infrastructure of the African American–owned barbershops to educate and identify men with health problems may prove to be an efficient and cost-effective model to positively impact a high-risk and medically hard-to-reach group and the communities in which they reside.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Norm Nixon, BBHOP national spokesperson; Donte Kelly, national BBHOP coordinator; Margo LaDrew, BBHOP program director; Courtney White, executive assistant to Dr Releford; Damon Forcey, vice president of community affairs, BBHOP; Dwayne Thomas, vice president of corporate relations, BBHOP; Robert Branscomb, vice president of logistics, BBHOP; Larry Proctor, PhD, Louisiana program director; Carol Adams, PhD, secretary of human services, State of Illinois; California Congresswoman Maxine Waters; Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas; and Danielle Osby, assistant to Dr Yancey.

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by a grant to the Diabetes Amputation Prevention Foundation from the Abbott Fund, to RAND from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars, to Charles R. Drew University from the National Institutes of Health (RR019234, RR003026 and MD000182), and to UCLA from the Centers for Disease Control REACH US Initiative (U58DP000999-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ, Rodgers SG. Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by Black men. J Am Acad Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20:555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor KL, Davis JL, III, Turner RO, et al. Educating African American men about the prostate cancer screening dilemma: a randomized intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2179–2188. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson S, List M, Sinner M, Dai L, Chodak G. Educating African-American men about prostate cancer: impact on awareness and knowledge. Urology. 2003;61:308–313. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor KL, Turner RO, Davis JL, 3rd, et al. Improving knowledge of the prostate cancer screening dilemma among African American men: an academic-community partnership in Washington, DC. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:590–598. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen DJ, Beresford S, Vu T, Shu J, Feng Z. Design and baseline findings for a randomized intervention trial of dietary change in religious organizations. Prev. Med. 2004;39:602. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linnan LA, Ferguson YO. Beauty salons: a promising health promotion setting for reaching and promoting health among African American women. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:517–530. doi: 10.1177/1090198106295531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Cohn JA, White M, Weldon RN, Wu P. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors among African American women: the Black cosmetologists promoting health program. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program: Eric Whitaker. [Accessed July 1, 2009];Publications and Research. http://www.rwjf.org/reports/npreports/scholarseEricWhitaker.htm.

- 10.Simons V, Salner A, Harrington J. In: Personal Communication—Role of Bar-bershops in Health Outreach. Stanley K, Frencher Jr, editors. Los Angeles, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong W, Saunders E. Community programs to increase hypertension control. J Natl Med Assoc. 1989;(suppl):13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowart LW, Brown B, Biro DJ. Educating African American men about prostate cancer: the barbershop program. Am J Health Studies. 2004;19:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake BE, Keane TE, Mosley CM, et al. Prostate cancer disparities in South Carolina: early detection, special programs, and descriptive epidemiology. J S C Med Assoc. 2006;102:241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart A, Jr, Bowen DJ. The feasibility of partnering with African-American barbershops to provide prostate cancer education. Ethn Dis. 2004 Spring;14(2):269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart A, Jr, Underwood SM, Smith WR, et al. Recruiting African-American barbershops for prostate cancer education. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess PL, Reingold JS, Jones J, et al. Barbershops as Hypertension Detection, Referral, and Follow-Up Centers for Black Men. Hypertension. 2007;49:1040–1046. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt CL, Theresa A, Wynn Ivey Lewis, et al. Development of a barbershop-based cancer communication intervention. Health Educ. 2009;109:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight M. The Barbershop Initiative. [Accessed June 30, 2009]; http://www.state.nj.us/health/ccp/index.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnus M. Barbershop Nutrition Education. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004;36:45–46. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DMM. Distrust, Race, and Research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gesler WM, Arcury TA, Skelly AH, Nash S, Soward A, Dougherty M. Identifying diabetes knowledge network nodes as sites for a diabetes prevention program. Health Place. 2006;12:449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action : a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow L. Why health promotion lags knowledge about healthful behavior. Am J Health Promot. 2001;15:388–390. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stokols D, Grzywacz JG, McMahan S, Phillips K. Increasing the health promotive capacity of human environments. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18:4–13. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grier S, Bryant CA. Social marketing in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:319–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maibach EW. Recreating communities to support active living: a new role for social marketing. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18:114–119. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yancey AK. Facilitating health promotion in communities of color. Cancer Res Ther Control. 1999;8:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yancey AK. Social Ecological Influences on Obesity Control: Instigating Problems and Informing Potential Solutions. Obesity Management. 2007 Apr;3:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Bureau of the Census, Urban Institute, GeoLytics Inc. Long form release 3.0 ed. Brunswick, NJ: Geolytics; 2006. [Accessed July 1, 2009]. CensusCD neighborhood change database (NCDB) 1970–2000 tract data: selected variables for US Census tracts for 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 and mapping tool. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US); Behavioral Surveillance Branch. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. [Accessed July 1, 2009]; http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS3714.

- 32.Smith SC, Jr, Clark LT, Cooper RS, et al. Discovering the Full Spectrum of Cardiovascular Disease: Minority Health Summit 2003: Report of the Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Hypertension Writing Group. Circulation. 2005;111:e134–e139. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157743.54710.04. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steckler A, Goodman R. How to institutionalize health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot. 1989;3:34–44. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-3.4.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Victor RG, Ravenell JE, Freeman A, et al. A barber-based intervention for hypertension in African American men: design of a group randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2009;157:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yancey A, Winfield D, Larsen J, et al. “Live, Learn and Play:” building strategic alliances between professional sports and public health. Prev Med. 2009;49:322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for Academic and Clinician Engagement in Community-Participatory Partnered Research. JAMA. 2007;297:407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]