Abstract

Ultrasound application in the presence of microbubbles has shown great potential for non-viral gene transfection via transient disruption of cell membrane (sonoporation). However, improvement of its efficiency has largely relied on empirical approaches without consistent and translatable results. The goal of this study is to develop a rational strategy based on new results obtained using novel experimental techniques and analysis to improve sonoporation gene transfection. We conducted experiments using targeted microbubbles that were attached to cell membrane to facilitate sonoporation. We quantified the dynamic activities of microbubbles exposed to pulsed ultrasound and the resulting sonoporation outcome and identified distinct regimes of characteristic microbubble behaviors: stable cavitation, coalescence and translation, and inertial cavitation. We found that inertial cavitation generated the highest rate of membrane poration. By establishing direct correlation of ultrasound-induced bubble activities with intracellular uptake and pore size, we designed a ramped pulse exposure scheme for optimizing microbubble excitation to improve sonoporation gene transfection. We implemented a novel sonoporation gene transfection system using an aqueous two phase system (ATPS) for efficient use of reagents and high throughput operation. Using plasmid coding for the green fluorescence protein (GFP), we achieved a sonoporation transfection efficiency in rate aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs) of 6.9% ± 2.2% (n = 9), comparable with lipofection (7.5% ± 0.8%, n = 9). Our results reveal characteristic microbubble behaviors responsible for sonoporation and demonstrated a rational strategy to improve sonoporation gene transfection.

Keywords: Sonoporation, Ultrasound, Microbubbles, Intracellular delivery, Gene transfection, High speed videomicroscopy, Aqueous two phase system

1. Introduction

Safe and efficient transport of therapeutic genetic materials across the cell plasma membrane is critical for successful gene therapy. Although viral vectors are efficient for gene transfection, the associated inflammatory and adverse immunogenic responses post safety concerns, motivating development of safer, non-viral delivery techniques [1–3]. Ultrasound techniques have shown potential for non-viral gene delivery both in vitro and in vivo [4–7]. Sonoporation uses ultrasound to excite microbubbles to reversibly disrupt the cell membrane, thereby transporting impermeant agents into cell cytoplasm without the use of viral vectors [8–11]. Since ultrasound application can non-invasively target a tissue volume with a superior safety profile, the technique is particularly advantageous for treating various human diseases including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and thrombosis [12–15]. However, compared to viral or other delivery methods such as lipofection and electroporation, sonoporation generally has relatively low efficiency [12]. Effort to optimize ultrasound parameters to enhance delivery efficiency [16–18] has been limited to empirical screening without detailed knowledge of the ultrasound induced microbubble activities and their roles in sonoporation. This is largely due to the complexity of ultrasound driven microbubble dynamics and the lack of appropriate measurement techniques.

Direct optical imaging has revealed the details of single microbubble dynamics including high speed fluid micro-jet that penetrates cell membrane [8], expansion and contraction of a microbubble that can deform and disrupt cell membrane [11,19]; and compression of bubble against cell by acoustic radiation force that can rupture the membrane [20]. These single cell studies have focused on the dynamic behaviors of single bubbles exposed to short ultrasound pulses, yet typical sonoporation delivery approaches often involve a large number of cells subjected to long ultrasound duration or multiple pulses in the presence of a population of microbubbles. For example, microbubbles and drugs are often co-administered intravenously in vivo while ultrasound is applied for a period of 10–60 s. For in vitro delivery, cells, either adherent or in suspension, are mixed with microbubbles distributed in the bulk solution of extracellular medium. In these cases, long ultrasound application or multiple pulses can induce highly dynamic activities of microbubbles with inter-bubble interactions distinctly different from single bubble exposed to short ultrasound pulses. Detailed and complete understanding of such highly dynamic systems relevant for sonoporation has not been obtained.

The goal of this study is to develop a rational strategy to improve ultrasound-mediated gene transfection using targeted microbubbles. This study includes two parts. First, we used human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) as a model system to investigate the general processes of microbubble dynamic behaviors driven by pulsed ultrasound exposures and experimental conditions for sonoporation mediated intracellular uptake and cell viability. In addition to transmembrane transport, sonoporation gene transfection, like other non-viral gene transfection approaches, faces the limitation of low diffusion coefficient in the crowded cytoplasm and nucleocytoplasmic transport. Non-viral gene transfection is often cell type dependent and particularly difficult for non-dividing or primary cells. Thus in the second part of this study, we used rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs), known as hard to transfect, as a model system to demonstrate our rational strategy to improve sonoporation gene transfection.

Targeted microbubbles incorporate ligands on their encapsulating shells to selectively bind to specific receptors expressed on the cell membrane [21–24], enabling ultrasound molecular imaging by recognizing molecular markers associated with diseases including inflammation, ischemia–reperfusion injury, angiogenesis, and thrombosis [21,25–32]. With the potential to load therapeutic agents [23,24,33–36] and to retain within specific tissue volume [37,38], targeted microbubbles provide a unique opportunity for combined ultrasound imaging and targeted drug delivery with enhanced efficacy and reduced side effects [31,39,40]. We used high speed videomicroscopy to capture the complete dynamic process of the initially cell-bound microbubbles exposed to ultrasound pulses. We quantified the characteristic bubble activities responsible for intracellular uptake and cell survival. Based on detailed investigation of pore size and delivery efficiency in sonoporation affected by ultrasound parameters at the individual cell level, we developed a ramped pulse scheme to improve sonoporation gene transfection.

For typical in vitro transfection, the agents to be delivered are generally mixed in the bulk medium solution with adherent or suspended cells. The large volume of medium required in such systems makes inefficient use of the often expensive reagents. In this study, we implemented a novel sonoporation system using a polyethylene glycol/dextran (PEG/DEX) aqueous two phase system (ATPS) [41,42] to achieve efficient use of plasmid and high throughput operation by confining GFP plasmid in the small volume (e.g. µL) of DEX phase for gene transfection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and targeted microbubbles

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were used for experiments to investigate the details of microbubble dynamics and sonoporation. The cells cultured in flasks in complete human endothelial growth medium (Lonza CC-3124, Walkersville, MD) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were plated into fibronectin coated 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) for one day to reach 90–100% confluency for experiments. Rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs) were used for gene transfection experiments. The cells were maintained in flasks in complete growth medium consisting of DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 3737 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were plated in fibronectin coated glass-bottom 35 mm dish for one day to reach 70% confluency at the time of experiments.

Targestar™-SA (Targeson, La Jolla, CA) microbubbles were used for sonoporation. Biotinylated anti-human CD31 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was used to attach the microbubbles to HUVECs. Biotinylated anti-mouse CD51 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) was used to attach the microbubbles to RASMCs. To allow the Targestar™-SA microbubbles to bind with the specific antibody, 8 µL microbubbles (1 × 109 bubble/mL) was mixed with 2 µL of an tibody (0.5 mg/mL) and incubated for 20 min at room temperature before the addition of 480 µL complete culture medium to reach 1.6 × 107 microbubbles/mL and 2 µg/mL for antibody.

To conjugate the microbubbles with cells, the culture medium from the cell-seeded dish was removed followed by immediate addition of 20 µL of the above solution containing the antibody/ microbubble complexes. Then the petri dish was flipped over so that the attached cells faced downward to facilitate attachment of the microbubbles with the cells via specific ligand–receptor binding. When added to the dish immediately after removal of the culture medium from the dish, the small amount, i.e. 20 µL, of solution containing the antibody/microbubbles allowed the fluid to spread out on the monolayer to form a thin liquid layer covering all the adherent cells on the dish bottom. The small volume of solution made it possible for the thin liquid layer to stay on the cells without dripping when the dish was flipped upside down to allow binding of the microbubbles with cells. After 10 min, the dish was flipped back and gentle washing was performed with complete culture medium to remove unbound microbubbles before experiments.

2.2. Experimental setup and ultrasound system

As shown in Fig. 1A and described before [10], the 35 mm petri dish with cells and targeted microbubbles was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti–U, Melville, NY) equipped with a 20× superfluo objective (Nikon MRF00200, Melville, NY; NA 0.75). A single element planar transducer (1.25 MHz, Advanced Devices, Wakefield, MA), driven by a waveform generator (Agilent Technologies 33250A, Palo Alto, CA) and a 75 W power amplifier (Amplifier Research 75A250, Souderton, PA), was used to generate ultrasound pulses with various acoustic pressure, duration of each pulse (pulse duration), pulse repetition frequency (PRF) or pulse repetition period (PRP), and duty cycle (ratio of pulse duration over PRP). The transducer was pre-characterized in free field using a 40 µm calibrated needle hydrophone (Precision Acoustics HPM04/1, UK). To avoid standing waves in the dish and to accommodate microscopic imaging, the transducer was mounted at a 45° angle with its active surface submerged in medium and ∼7.5× mm (Rayleigh distance) from the cells.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup of ultrasound excitation of targeted microbubbles attached to cells for sonoporation. Fluorescence imaging was used to detect intracellular delivery and cell viability, while high speed videomicroscopy was used to monitor ultrasound-induced bubble activities.

2.3. High-speed videomicroscopy and characterization of ultrasound-induced bubble activities

To capture the evolution of microbubble behaviors driven by ultrasound pulses, we used a high speed camera (Photron FASTCAM SA1, San Diego, CA) with a frame rate of 20 Kframes/s with 512 × 512 pixels in each frame. To characterize ultrasound-induced microbubble behaviors, we first calculate the “average rate of active size change” as 〈|ΔR|/TUS〉, where ΔR is the difference of bubble radius before and after an ultrasound pulse and TUS is the pulse duration. The average rate was computed as the mean of |AR|/TUS from all pulses. The “total displacement of bubble” was calculated as the sum of the absolute displacements of bubbles occurred during each pulse.

2.4. Gas diffusion model of microbubbles

The microbubbles used in this study are stabilized perfluorocarbon gas bubbles encapsulated by a lipid shell, which prevents gas diffusion and the effects of the surface tension. To assess the change of microbubble properties after an ultrasound pulse, we fit the radius–time curve of microbubble during the “ultrasound-off” period using the following gas diffusion model [43]:

| (1) |

where r(t) is the bubble radius, L is the Ostwald's coefficient (air, L = 0.02; PFC, L = 0.0002), and Dω is gas diffusivity. In 3.2% dextran solution, Dω = 1.46 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 based on oxygen diffusion [44] and in perfluorocarbon (PFC) Dω = 0.7 × 10−5 cm2 s−1. Rshell is the resistance of the shell to gas permeation. For free bubble without shell, Rshell = 0; air bubble with lipid shell Rshell = 104 s m−1; PFC bubble with lipid shell, Rshell = 107 s m−1. σshell is the surface tension of the shell. For free bubble without shell in 3.2% dextran solution [45], CTshell = 72 mN m−1; lipid shelled bubbles, σshell = 0. Pa is the hydrostatic pressure outside the bubble (Pa = 101.3 kPa), and f is the ratio of the gas concentration in the bulk medium over that at saturation (degassed solution, f= 0). The goodness of the fitting was evaluated using , where yi is the observed value,fi the associated modeled value, and ӯ the mean value.

2.5. Fluorescence imaging and sonoporation outcome

Propidium iodide (PI) is normally excluded from intact cells. We added PI (100 µM) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in the extracellular medium and detected intracellular uptake of PI as fluorescent indicator of cell membrane disruption and transmembrane transport. We assessed cell viability using calcein AM, a cell-permeable, non-fluorescent compound. After sonoporation, calcein AM was added into the extracellular medium at a final concentration of 1 µM. In live cell, the non-fluorescent calcein AM is converted into green-fluorescent calcein, after acetoxymethyl ester hydrolysis by intracellular esterases.

As described previously [10], for fluorescent imaging, a monochro-mator (DeltaRAMX™ PTI, Birmingham, NJ) was used to excite the samples at 538 nm for PI and 488 nm for calcein and GFP with appropriate dichroic filters to detect the emission signals at 610 nm (PI) and 520 nm (calcein) simultaneously. The fluorescent images were collected using a cooled CCD camera (Photometrics QuantEM, Tuscon, AZ) and then pseudo-colored using Matlab.

The cells with attached bubbles were counted toward the total number of cells. The percentage of calcein positive cells over the total number of cells is defined as cell viability, the percentage of PI and calcein positive cells over the total number of cells as the delivery rate, and the mean PI fluorescence intensity per cell as the delivery efficiency.

2.6. Size of pores generated by ultrasound excitation of microbubbles

As an ultrasound excited microbubble attached to a cell generates membrane disruption, i.e., pore, PI in the extracellular medium will diffuse into the cell cytoplasm and intercalate with DNA and/or RNA molecules, producing PI fluorescence signal. To estimate the size of a single pore, we recorded continuously the intracellular PI fluorescence intensity until 5 min post ultrasound. We calculated the pore radius based on the temporal change of the total intracellular PI fluorescence intensity after sonoporation, as described previously [46], assuming the transport of PI into cells as a quasi-steady state diffusion problem through a small hole in a plane.

2.7. Sonoporation system for gene transfection using aqueous two phase system (ATPS)

PmaxFP™-Green-C plasmid (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), encoding the GFP, was used in gene transfection experiments in adherent RASMCs. We used a DEX/PEG ATPS to spatially confine and localize GFP plasmids within the DEX phase near the cells. As described previously [42], polyethylene glycol (PEG) (2.5% w/w) (35 kDa, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and dextran (3.2% w/w) (500 kDa, Pharmacosmos, Copenhagen, Denmark) were used to form an ATPS. The aqueous DEX and PEG phases were prepared in culture medium separately before use. The GFP plasmid was dissolved in DEX to reach a final concentration of 10 µg/mL.

Before gene transfection, the culture medium was removed and 3 mL PEG was added in the dish with the RASMCs and attached microbubbles. Then multiple, discrete dextran droplets (0.4 µL) containing the GFP plasmid were added in the dish to form a separated phase at multiple treatment sites. After patterning the DEX droplets, which spread over the cells, additional 5–7 mL PEG was added to the dish without disturbing the patterning to allow immersion of the active element of the ultrasound transducer. Ten minutes after ultrasound exposure, the ATPS was removed from the dish and replaced with fresh complete culture medium. GFP expression was detected after 24 h incubation. Since the plasmid was only present within the DEX phase, only the cells covered by the DEX droplets will be transfected. The GFP positive cells relative to the total number of cells was defined as gene transfection efficiency.

Lipofection transfection was performed using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Lipofectamine 2000 and plasmid were added to dextran solution at the ratio of 1/1 (w/v) to allow transfection using the same DEX/PEG ATPS as the sonoporation transfection experiments. After incubation for 4 h, the ATPS was removed and replaced with fresh complete culture medium. GFP expression efficiency was analyzed 20 h later. The percentage of GFP positive cells relative to the total number of cells was defined as gene transfection efficiency.

2.8. Kinetics of intracellular transport of GFP plasmid

We labeled the GFP plasmid with nucleic acid stain fluorophore BOBO™-3 iodide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by mixing BOBO-3 with plasmid (molecule ratio of 1 dye molecule per 30 base pairs) for 30 min at the room temperature in the dark. The labeled plasmid was then used in gene transfection experiments. After sonoporation or lipofection, the cells were washed to remove the BOBO-labeled plasmid in the extracellular medium. Live cell imaging was then performed to monitor the internalized BOBO–plasmid complexes using a Carl Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope with an AxioCam camera (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) and Pecon XL S1 live-cell incubator system (Pecon GmbH, Erbach, Germany), which is a humidified thermostatic chamber at 37 °C supplied with 5% CO2. The time-lapse bright field images and fluorescent images were captured every 30 min over 24 h.

3. Results

The use of targeted microbubbles in this study enabled a controlled starting point for ultrasound excitation of microbubbles in relation to cells. We ensured consistent experimental conditions by controlling the number of microbubbles attached to each cell. Fig. 2A shows a typical bright field image of cells with stably attached microbubbles before ultrasound application. In typical experiments, about 7% of cells had no bubbles, 60% of cells had one bubble, 22% of cells two bubbles, 8% with three bubbles, and 3% with more bubbles (Fig. 2B). The majority of the microbubbles had a radius of 2.2–3.1 µm (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

(A) A typical bright filed image of cells with attached bubbles. (B) Distribution of microbubbles per cell obtained from 5 typical experiments. (C) Distribution of bubble radii obtained from 5 typical experiments.

3.1. Characteristic behaviors of microbubbles induced by pulsed ultrasound

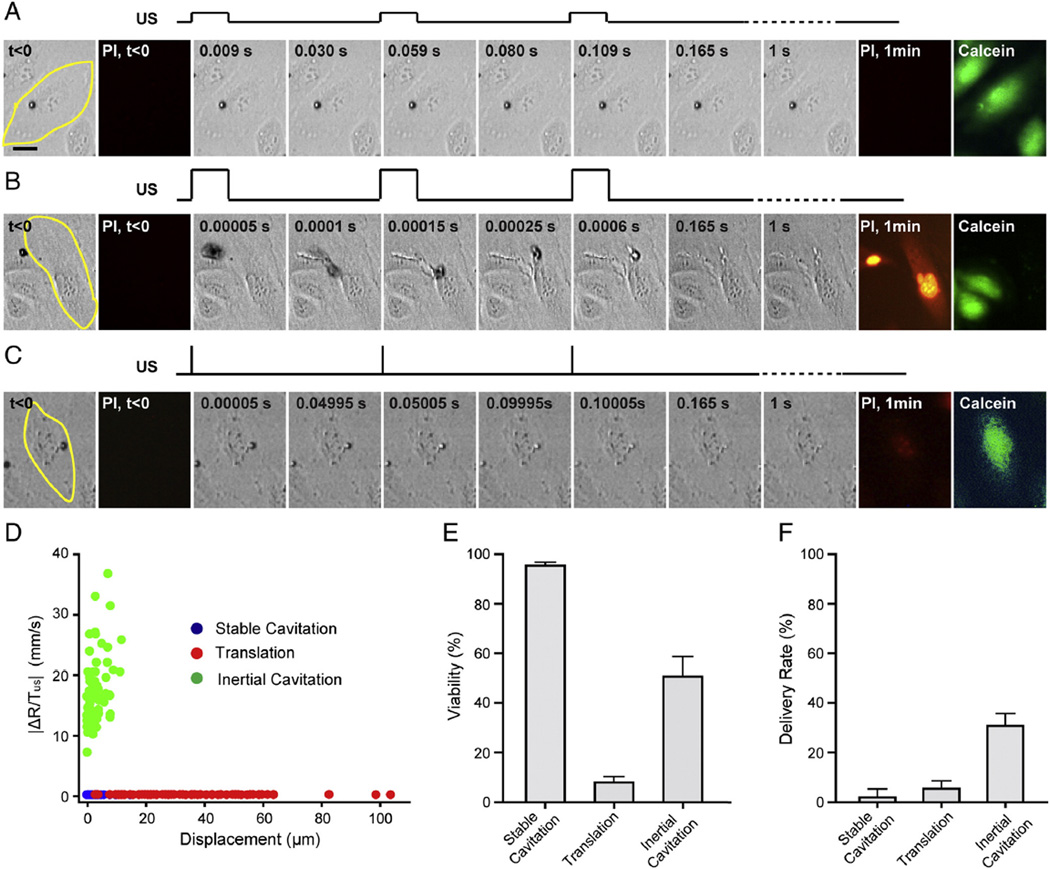

We first examined the responses of a population of initially cell-bound microbubbles to pulsed ultrasound exposures with various combinations of ultrasound parameters (e.g. acoustic pressure from 0.06 to 0.8 MPa, pulse duration from 8 µs to 10 ms, PRF from 20 Hz to 1 kHz, and total application duration of 1 s). While the microbubbles appeared to exhibit a broad range of complex dynamic activities, characteristic behaviors emerged when 〈|ΔR/TUS|〉 and the total displacement of microbubbles was considered. Despite the large parameter space of ultrasound exposures, we observed that the seemly widely varied microbubble activities can be characterized by three basic types of behaviors with key common features, as shown by the examples in Fig. 3A–C and Supplemental videos 1–3.

Fig. 3.

Characteristic bubble dynamics induced by pulsed ultrasound exposures. (A) Selective images showing stable cavitation of microbubbles with minimal translational movement. The cell was outlined in yellow. Acoustic pressure was 0.06 MPa, duty cycle 20%, and PRF 20 Hz. A schematic illustration of the pulsed ultrasound exposure was plotted above the images. No PI uptake was observed, and cell viability indicated by calcein retention. (B) Coalescence and translation of microbubbles. Acoustic pressure 0.4 MPa, duty cycle 20%, and PRF 20 Hz. PIfluorescence indicates cell membrane disruption. The absence of calcein indicated cell death. (C) Inertial cavitation with minimal displacement showing shrinkageof microbubbles after each ultrasound pulse before eventually disappeared. Acoustic pressure was 0.4 MPa, duty cycle 0.016%, and PRF 20 Hz. PI uptake was observed and calcein AM assay showed cell survived. (D) Characterization of bubble dynamics by the average rate of active bubble size change and total displacement of microbubbles. Data include 257 microbubbles. (E) Cell viability. (F) PI delivery rate (n = 6 for each group). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The first characteristic type of bubble behaviors was signified by small or no change in size and location of microbubbles (Fig. 3A and Supplemental video 1). Here, microbubbles typically exhibited limited translational movement (<1–2 µm) with no or slight reduction of radius after each pulse (Fig. 3D), suggesting small amplitude expansion and contraction of microbubbles typical of stable cavitation. Most cells remained viable and the delivery rate induced by this type of bubble activities, as measured by PI uptake, is low (Fig. 3A, E, and F).

If a higher acoustic pressure was used (e.g. 0.43 MPa, the same duty cycle 20%), a distinctively different type of dynamic behaviors emerged which was dominated by microbubble coalescence/aggregation and significant translational movement (Fig. 3B, Supplemental video 2). In these cases, the initially cell-bound microbubbles detached from the cells almost immediately (e.g. b0.5 ms) after ultrasound application and subsequently moved rapidly toward each other to form aggregates and coalesce. This is due to the strong attractive forces among bubbles (the secondary acoustic radiation force or Bjerknes force [47,48]), which overcame the receptor–ligand binding between the bubbles and cells. Aggregated and coalesced bubbles continued to move rapidly across cells in their path, leading to death of many cells (Fig. 3B, E and F). Although the changes in microbubble sizes were significant during the first ultrasound pulses, translation and coalescence of bubbles in these cases were very short lived (<0.1–0.2 s), resulting in low overall values of 〈|ΔR/TUS|〉 (Fig. 3D).

The third type of bubble behaviors was characterized by large rate of active size change and limited translation movement of microbubbles (Fig. 3C and Supplemental video 3). In these cases, significant reduction of bubble size was observed after each pulse, indicating the occurrence of inertial cavitation accompanied by large amplitude expansion/ contraction driven by high acoustic pressures (e.g. 0.43 MPa). Limited translational movement of microbubbles was due to the short pulse duration (e.g. 8 µs), during which the bubbles were not able to gain enough momentum to detach from the cells. Compared to the other two types of bubble dynamics, this type of bubble behaviors signified by inertial cavitation generated the highest intracellular delivery while maintaining good level of cell viability (Fig. 3E and F). Fig. 3D shows the clustering of 〈|ΔR/TUS|〉 and total displacement of 257 bubbles exposed to pulsed ultrasound exposures obtained from 36 experiments where acoustic pressure ranged from 0.06 to 0.4 MPa, duty cycle 0.016–20%, PRF 20 Hz, and total duration 1 s. Correlation of these characteristic parameters with sonoporation outcome suggests that inertial cavitation generated efficient membrane disruption and delivery while significant displacement of aggregated/ coalesced bubbles caused cell death (Fig. 3E and F).

3.2. Ultrasound induced microbubble shell disruption and gas diffusion

We examined how microbubbles change after an ultrasound pulse to assess whether ultrasound application disrupted the encapsulating shell and affect microbubble stability.

For microbubbles exhibiting stable cavitation, their size stayed unchanged or decreased slightly after an ultrasound pulse and during the following ultrasound-off period, as shown by the example in Fig. 4A and B. Fitting of the time-dependent radii during the ultrasound-off period with the gas diffusion model of microbubble in Eq. (1) show that these bubbles behaved like PFC gas bubbles with an intact shell.

Fig. 4.

Bubble dissolution after stable and inertial cavitation. (A) Selected time-lapse images of a bubble undergoing stable cavitation. (B) Radius–time curve of the bubble in (A) after the 1st and 2nd ultrasound pulse and fitting using the diffusion model. Acoustic pressure was 0.06 MPa, duty cycle 20%, PRF 20 Hz. (C) Selected time-lapse images of a bubble undergoing inertial cavitation. (D) Radius–time curve of the bubble shown in (C) after 1st and 2nd ultrasound pulses and fitting with diffusion model. Acoustic pressure 0.4 MPa, duty cycle 0.016%, PRF 20 Hz.

In contrast, microbubbles after inertial cavitation not only sustained a significant size decrease after an ultrasound pulse, as shown by the example in Fig. 4C and D (arrows at t = 0 and 50 ms), they also continued to decrease substantially in size during the “ultrasound-off” periods between pulses, indicating diffusion of gas and disruption of the encapsulating shell. Fitting of the radius–time curves during the 1st ultrasound-off period indicates that the bubbles were without shell and composed of 45% ± 5% PFC and (55 ± 5) % air (n = 10, R2 = 0.9 ± 0.05) due to leakage of PFC gas and infusion of air into the bubbles. Fitting the radius–time curve after the 2nd pulse shows that the bubbles consisted of 12% ± 8% PFC and (88 ± 8)% air without shell (n = 10, R2 = 0.83 ± 0.07). The faster size reduction is attributed to a more dominate surface tension and higher content of the more diffusive air.

These results show that inertial cavitation significantly reduced microbubble radius during and after an ultrasound pulse. Such size reduction will influence how the bubbles respond to additional ultrasound pulses, due to higher inertial cavitation threshold for smaller bubbles.

3.3. Parameters affecting inertial cavitation and sonoporation outcome

The high efficiency of inertial cavitation in membrane poration is likely due to robust ultrasound excitation of microbubbles. Here we report our experimental results to demonstrate optimization of sonoporation parameters based on their impact on a population of microbubbles and correlated impacts on cells.

3.3.1. Number of ultrasound pulses

We conducted three sets of experiments using 20, 2, or 1 ultrasound pulse(s) respectively to examine the detailed correlation of bubble activities with delivery. Each ultrasound pulse was 8 µs in duration. Acoustic pressure of 0.43 MPa was used to generate inertial cavitation of microbubbles with minimal translational movement. PRF was 20 Hz for all experiments. Under these conditions, application of 20 pulses induced most cell death (viability 52% ± 10%, n = 5), while the viability increased to 72% ±11% (n = 5) and 95% ± 3% (n = 6) for two pulse and one pulse application respectively (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, delivery rate increased from 31% ± 5% to 44% ± 7% and 59% ± 5% with fewer pulses (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of number of pulses on sonoporation delivery. (A) Microbubbles in experiments using 20 ultrasound pulses (n = 6). Grouping of microbubbles into cohorts based on their effect on cells: cell death (red curves, 32 bubbles), PI delivery (blue curves, 20 bubbles), and no effect (green curves, 18 bubbles). (B) Microbubbles in experiments using 2 pulses (n = 6). (C) Microbubbles in experiments using 1 pulse (n = 5). Acoustic pressure 0.4 MPa, pulse duration 8 µs, and PRF 20 Hz. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We grouped the microbubbles into different cohorts based on the status of the cells to which the bubbles were attached: 1) bubbles associated with non-viable cells, 2) bubbles associated with viable cells with PI uptake, and 3) bubbles associated with viable cells without PI uptake. We only analyzed the cells that had one attached microbubble so that the delivery outcome can be directly related to the bubble activities. Fig. 5A–C shows that the three cohorts of microbubbles are clearly separated. Besides the group of bubbles that generated membrane disruption and PI uptake (blue curves in Fig. 5A–C), bubbles with larger initial radius tend to exist longer and cause cell death (red curves in Fig. 5A–C), while the bubbles that became too small quickly failed to induce PI uptake for all experiments (green curves in Fig. 5A–C). The bubbles in experiments using 20 pulses had the longest duration to impact the cells (although most of the bubbles were gone after 5 pulses) and caused most cell death (Fig. 5A–E). While it is possible that these bubbles were effective in disrupting the cell membrane, the longer impact time eventually caused cell death and significantly decreased the delivery rate.

3.3.2. Effect of acoustic pressure on sonoporation delivery

Our results show that application of one ultrasound pulse can effectively induce membrane disruption and application of more pulses decreased delivery rate due to high rate of cell death. We conducted experiments to test whether increasing the acoustic pressure of single ultrasound can improve sonoporation outcome. Using acoustic pressure of 0.4 MPa, 0.6 MPa, 0.8 MPa, and 1.6 MPa respectively, we found that higher acoustic pressure killed more cells (Fig. 6A) and that the delivery rate (percentage of PI positive cells) increased when pressure increased to 0.6 MPa but decreased with further increase of pressure (Fig. 6B). However, the delivery efficiency (PI uptake per cell) continued to increase and was markedly higher at 0.8 MPa and 1.6 MPa (Fig. 6C). More cells had higher PI uptake at higher acoustic pressures (Fig. 6D, F, H, and J). While the overall size distribution of microbubbles was similar for all experiments, grouping of the bubbles into different cohorts based on their impacts on cells shows that higher pressures excited a wider range of bubbles (more smaller bubbles) to deliver PI (blue bars in Fig. 6E, G, I, and K). More bubbles were excited and killed cells (red bars in Fig. 6E, G, I, and K).

Fig. 6.

Effects of acoustic pressure amplitude of single ultrasound pulse (pulse duration 8 µs) application on sonoporation delivery. (A) Viability, (B) delivery rate, (C) Delivery efficiency (average PI intensity per cell). n = 5 for each acoustic pressure. (D, F, H, and J) Distribution of intracellular PI intensity. (E, G, I and K) Size distribution of different cohorts of microbubbles grouped based on their roles in sonoporation: viable cells with PI uptake (blue bars), non-viable cell (red), viable cell without PI uptake (green). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

3.3.3. Effects of number of bubbles per cell on sonoporation

As shown by Fig. 2B, a cell may have different number of bubbles attached to it, although we used microbubble concentration to ensuremost of the cells had only one bubble attached to them, and the number of bubbles attached to a cell may impact the sonoporation outcome for that cell. In Fig. 7, we show the results obtained from 5 independent experiments where 1 pulse ultrasound exposure of duration of 8 µs at 0.6 MPa (Fig. 7A) or 1.6 MPa (Fig. 7B) was used. The percentages of cells were represented in three categories, viable without PI uptake (green), viable with PI uptake (blue), and non-viable cells (red). As the number of bubble/cell increased, the percentage of viable cells with PI uptake increased slightly until there were 4 bubbles/cell (blue curve in Fig. 7A), and then decreased when there were more bubbles attached to a cell. The large variations were observed because there were fewer cells with more bubbles attached to them (Fig. 2B). The decrease of viable cells with PI uptake is likely due to that the cells were killed due to the presence of more bubbles. These trends were also observed when higher acoustic pressure of 1.6 MPa was used (Fig. 7B), although the decrease of the percentage of cells with PI uptake occurred with fewer (3 vs. 4 bubbles/cell). The overall percentage was less than that in experiments using lower pressure, as expected.

Fig. 7.

Effects of number of bubbles per cell on sonoporation delivery in terms of percentage of cells that were non-viable (red curves), or viable without PI uptake (green curves), or viable with PI uptake (blue curves). (A) Experiments (n = 5) using 1 pulse ultrasound exposure with duration8 µs, acoustic pressure 0.6 MPa. (B) Experiments (n = 5) using 1 pulse ultrasound exposure with duration 8 µs, acoustic pressure 1.6 MPa.

3.4. Size of pores in sonoporation and improvement of delivery efficiency

The size of membrane disruptions, or pores, can be a limiting factor for delivery of macromolecules such as genes into cells. Since bubbles decreased in size significantly after inertial cavitation (Fig. 4D), we hypothesize that a ramped pulse schemeismore effective in exciting the microbubbles to induce membrane disruption. Here we report results of pore size distribution and sonoporation outcome from experiments using three different ultrasound exposure schemes: 1) one pulse, 2) two pulses with equal amplitude, and 3) two pulses with ramped amplitude where the 2nd pulse had higher pressure than the 1st pulse.

We estimated the size of pores from the measured time-dependent PI fluorescence intensity in individual cells. As shown by the example in Fig. 8A, intracellular transport of PI induced through a pore by an attached microbubble increased the total PI fluorescence intensity, which eventually reached a stable level (Fig. 8B) with resealing of the pore. Larger pores were generated by application of two pulses, especially with amplitude ramping, than a single pulse (Fig. 8C). For example, the percentage of pores with diameters > 25 nm increased from 5% (7 out of 140) with one pulse application to 16.4% with two pulses of equal amplitude, and reached to 29.3% with two pulses with ramped amplitude, corresponding to the fact that more cells had higher amount of PI uptake (Fig. 8D), suggesting that the 2nd pulse with higher pressure generated more robust response of the microbubbles (Fig. 8E). Although ramped pulses decreased cell viability (Fig. 8F) and delivery rate (Fig. 8G), the ability to generate more larger pores is desirable for delivering macromolecules such as plasmid.

Fig. 8.

(A) Intracellular transport of PI. (B) Total PI fluorescence after sonoporation. (C) Sizes of pores generated in sonoporation using different ultrasound conditions: 1 pulse (0.4 MPa, 8 µs), 2 pulses with equal amplitude (0.4 MPa, 8 µs, pulse interval 0.05 s), and 2 pulses with ramped amplitude (0.4 MPa and 0.6 MPa, pulse duration 8 µs, pulse interval 0.05 s). n = 140 for each condition. (D) Distribution of intracellular PI uptake for the three ultrasound conditions. (E) Representative radius–time curve of the bubbles (n = 10 for each condition). (F) Cell viability. (G) Delivery rate. n = 6 for each group.

3.5. Rationally designed strategy to improve gene transfection

For gene transfection experiments, we used a DEX/PEG ATPS for efficient use of GFP plasmid by confining the plasmid within the DEX phase. As shown by the example in Fig. 9A, BOBO-labeled GFP plasmids were confined within DEX droplets covering regions of RASMCs in the same monolayer. This system not only allowed efficient use of plasmid, but also enabled patterned delivery/transfection as well as improved throughput in sonoporation delivery.

Fig. 9.

(A) Bobo/plasmid confined in patterned DEX droplets using a DEX/PEG ATPS. (B) GFP transfection in RASMCs. (C) Superimposed image of bright filed image with images of GFP expression. (D) Gene transfection efficiency. For experiments using 1 pulse (n = 6), acoustic pressure was 0.4 MPa. For 2 pulse exposure (n = 6) with equal amplitude, acoustic pressure was 0.4 MPa and pulse interval 0.05 s. For 2 pulses with ramped amplitude, the acoustic pressure was 0.4 MPa for the 1st pulse and 0.6 MPa for the 2nd pulse. The time interval was either 0.5 s (n = 6) or 0.05 s (n = 9). Pulse duration was 8 µs for all pulses. (E) The radius–time curves for bubbles exposed to 2 ramped pulses with 0.5 s and 0.05 s time interval. n = 10.

We successfully transfected the RASMCs with GFP plasmid by ultrasound excitation of targeted microbubbles (Fig. 9B and C) achieving transfection efficiency of 1.5 ± 0.8% (n = 9) using one pulse (0.43 MPa, duration 8 µs) or 3.0 ± 1.1% (n = 6) using two pulses with equal amplitude (0.43 MPa, duration 8 µs) and an interval of 0.05 s (Fig. 9D). Compared with the delivery rate of PI in HUVECs (43–60%, Fig. 8G) generated with the same ultrasound parameters, the low gene transfection efficiency may be due, at least in part, to the small percentage of large pores permitting intracellular transport of the GFP plasmid. This is consistent with the increased gene transfection efficiency (6.9% ± 2.2%, n = 9) achieved by application of two pulses with ramped amplitude (0.43 MPa for the 1st pulse followed by a pulse at 0.6 MPa) (Fig. 9D), which are shown to be able to generate more large pores (Fig. 8C and D). This transfection efficiency is comparable with lipofection (7.5 ± 0.8%, n = 9). Interestingly, the benefit of the 2nd pulse disappeared when interval of 0.5 s was used, resulting in a gene transfection efficiency of 2.4 ± 1.3% (n = 6) (Fig. 9D). In these cases, the bubbles shrank to smaller sizes after the longer delay (Fig. 9E).

3.6. Intracellular transport of plasmid in gene transfection

To gain insight of plasmid internalization and intracellular trafficking, we used live cell imaging to examine the kinetics of BOBO-labeled plasmid in the cells after sonoporation and lipofection. As shown by Fig. 10A, not all cells with BOBO/plasmid uptake after sonoporation expressed GFP in the end. In the cell that did express GFP, diminishing of the BOBO signal corresponded with the appearance of GFP signal around 4–8 h. The BOBO signal in other non-expressing cells disappeared well before 24 h (Fig. 10A and C), indicating degradation of the plasmid. In contrast, BOBO signal after lipofection decreased slower and was present 24 h after transfection (Fig. 10B and D) with a later GFP expression (∼12 h) (Fig. 10B).

Fig. 10.

(A) Time lapse images of intracellular delivery of BOBO–plasmid (middle panel) and GFP expression after sonoporation (bottom). (B) Live cell imaging of BOBO–plasmid and expression after lipofection. (C) 24 h after sonoporation. (D) 24 h after lipofection. The left panels in (C and D) are fluorescent images showing GFP expression. The middle panels show intracellular BOBO–plasmid complexes. The right panels are phase contrast images superimposed with fluorescent images of GFP and BOBO–plasmid.

4. Discussion

4.1. Large parameter space for sonoporation

The response of microbubbles to ultrasound excitation depends on a multitude of parameters including the center frequency of ultrasound pulses, acoustic pressure amplitude, pulse repetition frequency, duration of each pulse, and total application duration etc. It is a large parameter space considering variation of all these parameters. In this study, we chose the center frequency to be 1.25 MHz without varying it because this frequency is close to the resonance frequency (i.e. the Minnaert resonant frequency) of the microbubbles used in this study, which had an average radius of about 2.5 µm. The use of frequency close to the bubbles' resonant frequency is expected to generate robust response of individual microbubbles. However, the response of multiple or a population of microbubbles to pulsed ultrasound exposures was more complicated, particularly by the interaction of microbubbles. Microbubble interactions are greatly affected by the combined influence of acoustic pressure, PRF, and duration of each pulse. As shown by our results, a population of microbubbles subjected to pulsed ultrasound exposures, which is the typical setting in sonoporation studies, exhibited very complex dynamic behaviors. Coalescence of bubbles and large/rapid translation movement of bubbles overwhelming generate high rate of cell death, negatively affecting sonoporation outcome. Therefore we focused on investigating the responses of a population of microbubbles under the influence of pulsed ultrasound exposures their effects on sonoporation outcome.

Since the resonant frequency is mostly determined by microbubble diameter, shell properties, and gas content within the bubble, physical binding of bubbles to cell membrane is not expected to have significant effect on bubble response in the context of ultrasound frequency, although the presence of the cells in the vicinity of bubbles might influence the bubble oscillation and collapse behaviors. In addition, targeting of the microbubbles to cells increases the likelihood of impact of ultrasound-induced microbubble activities to the cells.

4.2. High speed videomicroscopy to investigate ultrasound induced microbubble activities

Sonoporation often uses pulsed ultrasound exposures with a center frequency of 1–3 MHz, pulse duration of µs–ms, PRF 10–100 Hz, and total application 1–100 s. The dynamic responses of microbubbles to such ultrasound exposures can exhibit features of multiple time scales spanning orders of magnitude. Imaging of these bubble dynamic activities is challenging.

The actual expansion/contraction and/or collapse of a microbubble driven by MHz ultrasound can only be resolved using ultrafast imaging with frame rate above several Mframes/s [8,11,49–53]. However, ultrafast imaging is not only high cost, but also limited by the small number of images (e.g. 10–30) or short recording time (e.g. several µs) restricting their utility in studying bubble dynamics when multiple pulses or longer ultrasound application is often used.

We used high speed videomicroscopy with frame rate of 20– 200 Kframes/s in this study. Capable of imaging for longer period of time (seconds), high speed imaging at frame rate of 20 Kframes/s also provides sufficient temporal resolution for capturing dynamic behaviors at a time scale of the pulse duration, typically several µs to tens of ms. The dynamic features associated with pulsed ultrasound exposures has a time scale of the pulse repetition period (or 1/PRF), i.e., 10–100 ms. Since the features of microbubble activities during the total duration represent repetitive behaviors, we focused our experiments with ultrasound duration of 1 s. We show that high speed imaging can capture the key features of the dynamic behaviors of a population of microbubbles at time scales relevant to pulsed ultrasound exposures.

4.3. Characteristic microbubble behaviors and their impact on intracellular delivery

The large parameter space (e.g. acoustic pressure, pulse duration, PRF, etc.) associated with pulsed ultrasound exposures can generate microbubble activities that are highly dynamic and varied, making quantitative analysis difficult.

In this study, by focusing analysis of bubble activities at the time scales corresponding to the pulse duration and pulse repetition period, we identified two characteristic factors that capture the key features of the bubble behaviors in sonoporation. The rate of active size change of microbubbles, which is calculated at the end of each pulse, captures the acute change incurred during the ultrasound pulse. Our previous study using ultrafast imaging has shown that such observed size reduction immediately after an ultrasound pulse is directly related to the amplitude of bubble expansion/contraction in cavitation [46]. The total displacement of microbubbles emphasizes the significant translational movement of large bubbles (from bubble aggregation/coalescence and growth via rectified diffusion) driven by the acoustic radiation force.

Reflective of the fundamental aspects of microbubble responses to ultrasound application, these characteristic factors quantitatively categorized microbubble behaviors into three distinct types. Robust collapse of microbubble (inertial cavitation) was most efficient in sonoporation.

4.4. Targeted microbubbles

We found that inertial cavitation of targeted bubbles generated by ultrasound pulses with short pulse duration and sufficient pressure is most efficient for sonoporation. The intimate contact of targeted microbubbles with cells (<100 nm [54]) ensured effective impact of microbubbles on cells and also increased cell vulnerability. We observed that the acoustic radiation forces associated with longer pulse duration can detach the initially cell-bound bubbles and result in aggregation/coalescence of microbubbles. Translation of the aggregated bubbles across the cell monolayer caused cell death.

4.5. Short term sonoporation outcome

To characterize ultrasound-induced microbubble activities and their effects on cells, we used PI as markers to assess the delivery rate and the delivery efficiency via the intracellular PI fluorescence intensity during or immediately after sonoporation. Although the delivery rate may be underestimated if small amount of PI uptake was not detected in some cells due to the sensitivity of the imaging system, use of PI enabled efficient investigation and correlation of the dynamic process of sonoporation with microbubble activities induced by different ultrasound parameters at the individual cell level. For example, we estimated the size of pores generated in sonoporation based on the measurements of the time-dependent intracellular transport of PI. The amount of PI uptake in a cell was used to assess delivery related to the pore size and duration.

Calcein assay used in this study may overestimate the cell viability because indication of live cells was based on esterase activity, which may still be present if the cells were in the early stages of apoptosis. We recently showed that targeted microbubbles excited by pulsed ultrasound can induce significant cell apoptosis exhibiting annexinV labeling, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, caspase activation and changes in nuclear morphology [55].

4.6. ATPS in sonoporation gene transfection

We used ATPS to confine GFP plasmid close to the adherent cells by stably partitioning the plasmid in DEX phase. Small droplets of DEX (i.e. 0.5–2.0 µL) was deposited onto the monolayer cells (with attached microbubbles) in PEG. DEX has a slightly greater density than PEG, causing the DEX droplets to sink and contact the cell monolayer. Spreading of the small DEX droplets over the cells in the monolayer retained the plasmid within the DEX close to the cells as the interfacial energy at the PEG–DEX interface prevents the plasmid from diffusing from DEX into the PEG phase. This eliminated the need to use large amount of plasmid in the entire volume of medium in the cell culture dish and reduced the amount of plasmid by as much as 20,000-fold because plasmid was confined in 0.4 µL DEX droplets instead of 8–10 mL solution in typical sonoporation experiments in a dish or similar container.

Both the DEX and the PEG used in our system are biocompatible and noncytotoxic, as demonstrated in lipofection transfection and previous studies that used cell microinjection of fluorophore-conjugated polymers such as dextran for cell tracing. The ATPS medium imposes no acoustic discontinuity at the interface of the two phases while confining the reagents within a fluid. Capable of placing multiple, discrete treatment sites within the same monolayer, our method enables not only efficient use of reagents but also high throughput operation.

4.7. Rational design of ultrasound exposures to improve sonoporation gene transfection

Unlike conventional sonoporation studies, where optimization is based on statistical association of ultrasound parameters with cell status without any knowledge of the microbubble activities during ultrasound application [17,56–58], our current study developed a rational scheme to improve sonoporation based on detailed analysis of microbubble behaviors and their correlation with delivery outcome at the individual cell level. Specifically, PI uptake and cell viability of an individual cell were correlated with the dynamic activities of the specific microbubble attached to that cell. We found that 1) inertial cavitation was most effective in generating membrane disruption; 2) the initial size and active life time of a bubble determined its role in sonoporation; and 3) ultrasound pulses with ramped amplitude efficiently generated larger pores for gene transfection.

4.8. Mechanism and processes involved in sonoporation-mediated gene transfection

In this study, we achieved a sonoporation transfection efficiency of 6.9% ± 2.2% in RASMCs, which is comparable with lipofection (7.5 ± 0.8%) and much higher than reported ultrasound transfection in RASMCs [59]. RASMCs are known to be difficult to transfect and the gene transfection efficiency we obtained is much lower than PI delivery rate (59% ± 5%) in HUVECs using the same ultrasound parameters. This may underline the importance of the size of the pores for different agents to be delivered (PI is 668 Da and the GFP plasmid ∼3000 kDa). As shown in Fig. 8C, the size of the pores generated in sonoporation ranged from several nm to 60 nm, but most of the pores are smaller than 25 nm, limiting intracellular transport of plasmid. Increased number of larger pores resulted in higher gene transfection efficiency when ramped pulse application was used (Figs. 8C and 9D).

After sonoporation, migration of plasmid toward nucleus and across the nucleic envelope may also affect successful gene expression [33,60–62]. For example, naked DNA in the cytoplasm may be degraded by resident cytosolic DNases before expression takes place [60]. Molecules smaller than 40 kDa can diffuse through nuclear pores, but macromolecule such as plasmid may not across the nuclear envelop efficiently by passive diffusion [62,63]. Additional studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms of how kinetics of plasmid inside the cells affects gene expression to further improve sonoporation gene transfection efficiency.

5. Conclusion

We developed a rational strategy to improve sonoporation gene transfection by optimizing ultrasound parameters to induce controlled and robust microbubble activities. By characterizing and correlating microbubble activities with sonoporation outcome, we identified three characteristic bubble behaviors and found that inertial cavitation of microbubbles generated the highest rate ofmembrane disruption and intracellular delivery. Based on how ultrasound parameters affected microbubble activities and sizes of the pores generated, we designed a ramped pulse scheme to improve gene transfection. We implemented a novel sonoporation system using ATPS that enabled efficient use of reagents and high throughput operation. Our results show that rational design of ultrasound parameters based on microbubble dynamics and impact on cells can be obtained to improve sonoporation gene transfection and delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Funding from the Beyster Foundation and NIH (CA116592) is acknowledged. We thank Dr. John Frampton for his assistance on ATPS and Dr. Jianping Fu for the use of live cell imaging system.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.05.039.

References

- 1.Waehler R, Russell SJ, Curiel DT. Engineering targeted viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:573–587. doi: 10.1038/nrg2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman ZC, Appledorn DM, Amalfitano A. Adenovirus vector induced innate immune responses: impact upon efficacy and toxicity in gene therapy and vaccine applications. Virus Res. 2008;132:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nayak S, Herzog RW. Progress and prospects: immune responses to viral vectors. Gene Ther. 2010;17:295–304. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li YS, Davidson E, Reid CN, McHale AP. Optimising ultrasound-mediated gene transfer (sonoporation) in vitro and prolonged expression of a transgene in vivo: potential applications for gene therapy of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsunoda S, Mazda O, Oda Y, Iida Y, Akabame S, Kishida T, Shin-Ya M, Asada H, Gojo S, Imanishi J, Matsubara H, Yoshikawa T. Sonoporation using microbubble BR14 promotes pDNA/siRNA transduction to murine heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;336:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Ding JH, Bekeredjian R, Yang BZ, Shohet RV, Johnston SA, Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB, Grayburn PA. Efficient gene delivery to pancreatic islets with ultrasonic microbubble destruction technology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:8469–8474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602921103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delalande A, Bureau MF, Midoux P, Bouakaz A, Pichon C. Ultrasound-assisted microbubbles gene transfer in tendons for gene therapy. Ultrasonics. 2010;50:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prentice P, Cuschieri A, Dholakia K, Prausnitz M, Campbell P. Membrane disruption by optically controlled microbubble cavitation. Nat. Phys. 2005;1:107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlicher RK, Radhakrishna H, Tolentino TP, Apkarian RP, Zarnitsyn V, Prausnitz MR. Mechanism of intracellular delivery by acoustic cavitation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006;32:915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.02.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan Z, Kumon RE, Park J, Deng CX. Intracellular delivery and calcium transients generated in sonoporation facilitated by microbubbles. J. Control. Release. 2010;142:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Wamel A, Kooiman K, Harteveld M, Emmer M, ten Cate FJ, Versluis M, de Jong N. Vibrating microbubbles poking individual cells: drug transfer into cells via sonoporation. J. Control. Release. 2006;112:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekeredjian R, Grayburn PA, Shohet RV. Use of ultrasound contrast agents for gene or drug delivery in cardiovascular medicine. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;45:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taniyama Y, Azuma J, Rakugi H, Morishita R. Plasmid DNA-based gene transfer with ultrasound and microbubbles. Curr. Gene Ther. 2011;11:485–490. doi: 10.2174/156652311798192851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie F, Everbach EC, Gao S, Drvol LK, Shi WT, Vignon F, Powers JE, Lof J, Porter TR. Effects of attenuation and thrombus age on the success of ultrasound and microbubble-mediated thrombus dissolution. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2011;37:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapoport NY, Kennedy AM, Shea JE, Scaife CL, Nam KH. Controlled and targeted tumor chemotherapy by ultrasound-activated nanoemulsions/microbubbles. J. Control. Release. 2009;138:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarnitsyn V, Rostad CA, Prausnitz MR. Modeling transmembrane transport through cell membrane wounds created by acoustic cavitation. Biophys. J. 2008;95:4124–4138. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meijering BD, Henning RH, Van Gilst WH, Gavrilovic I, Van Wamel A, Deelman LE. Optimization of ultrasound and microbubbles targeted gene delivery to cultured primary endothelial cells. J. Drug Target. 2007;15:664–671. doi: 10.1080/10611860701605088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feril LB, Jr., Ogawa R, Tachibana K, Kondo T. Optimized ultrasound-mediated gene transfection in cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1111–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marmottant P, Hilgenfeldt S. Controlled vesicle deformation and lysis by single oscillating bubbles. Nature. 2003;423:153. doi: 10.1038/nature01613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Yang K, Cui J, Ye JY, Deng CX. Controlled permeation of cell membrane by single bubble acoustic cavitation. J. Control. Release. 2012;157:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson CR, Hu X, Zhang H, Tlaxca J, Decleves AE, Houghtaling R, Sharma K, Lawrence M, Ferrara KW, Rychak JJ. Ultrasound molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis with an integrin targeted microbubble contrast agent. Invest. Radiol. 2011;46:215–224. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182034fed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufmann BA, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging with targeted contrast ultrasound. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrara KW, Borden MA, Zhang H. Lipid-shelled vehicles: engineering for ultrasound molecular imaging and drug delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:881–892. doi: 10.1021/ar8002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klibanov AL. Preparation of targeted microbubbles: ultrasound contrast agents for molecular imaging. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2009;47:875–882. doi: 10.1007/s11517-009-0498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klibanov AL. Ultrasound molecular imaging with targeted microbubble contrast agents. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2007;14:876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufmann BA, Sanders JM, Davis C, Xie A, Aldred P, Sarembock IJ, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis with targeted ultrasound detection of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 2007;116:276–284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leong-Poi H, Christiansen J, Heppner P, Lewis CW, Klibanov AL, Kaul S, Lindner JR. Assessment of endogenous and therapeutic arteriogenesis by contrast ultrasound molecular imaging of integrin expression. Circulation. 2005;111:3248–3254. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.481515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winter PM, Morawski AM, Caruthers SD, Fuhrhop RW, Zhang H, Williams TA, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Robertson JD, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Molecular imaging of angiogenesis in early-stage atherosclerosis with alpha(v)beta3-integrin-targeted nanoparticles. Circulation. 2003;108:2270–2274. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093185.16083.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leong-Poi H. Molecular imaging using contrast-enhanced ultrasound: evaluation of angiogenesis and cell therapy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;84:190–200. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinkov S, Coester C, Serba S, Geis NA, Katus HA, Winter G, Bekeredjian R. New doxorubicin-loaded phospholipid microbubbles for targeted tumor therapy: in-vivo characterization. J. Control. Release. 2010;148:368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong X, Zhao F, Shi M, Yang H, Liu Y. Polymeric microbubbles for ultrasonic molecular imaging and targeted therapeutics. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2011;22:417–428. doi: 10.1163/092050610X540440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavalieri F, Zhou M, Ashokkumar M. The design of multifunctional microbubbles for ultrasound image-guided cancer therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:1198–1210. doi: 10.2174/156802610791384180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tlaxca JL, Anderson CR, Klibanov AL, Lowrey B, Hossack JA, Alexander JS, Lawrence MB, Rychak JJ. Analysis of in vitro transfection by sonoporation using cationic and neutral microbubbles. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2010;36:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janib SM, Moses AS, MacKay JA. Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010;62:1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sirsi SR, Hernandez SL, Zielinski L, Blomback H, Koubaa A, Synder M, Homma S, Kandel JJ, Yamashiro DJ, Borden MA. Polyplex-microbubble hybrids for ultrasound-guided plasmid DNA delivery to solid tumors. J. Control. Release. 2012;157:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng X, Lv F, Liu L, Tang H, Xing C, Yang Q, Wang S. Conjugated polymer nanoparticles for drug delivery and imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2010;2:2429–2435. doi: 10.1021/am100435k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klibanov AL, Rychak JJ, Yang WC, Alikhani S, Li B, Acton S, Lindner JR, Ley K, Kaul S. Targeted ultrasound contrast agent for molecular imaging of inflammation in high-shear flow. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2006;1:259–266. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rychak JJ. Molecular Imaging of Carotid Plaque with Targeted Ultrasound Contrast. Springer. 2011, pp:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kooiman K, Foppen-Harteveld M, van der Steen AF, de Jong N. Sonoporation of endothelial cells by vibrating targeted microbubbles. J. Control. Release. 2011;154:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patil AV, Rychak JJ, Klibanov AL, Hossack JA. Real-time technique for improving molecular imaging and guiding drug delivery in large blood vessels: in vitro and ex vivo results. Mol. Imaging. 2011;10:238–247. doi: 10.2310/7290.2011.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tavana H, Jovic A, Mosadegh B, Lee QY, Liu X, Luker KE, Luker GD, Weiss SJ, Takayama S. Nanolitre liquid patterning in aqueous environments for spatially defined reagent delivery to mammalian cells. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:736–741. doi: 10.1038/nmat2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavana H, Mosadegh B, Takayama S. Polymeric aqueous biphasic systems for non-contact cell printing on cells: engineering heterocellular embryonic stem cell niches. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:2628–2631. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrara K, Pollard R, Borden M. Ultrasound microbubble contrast agents: fundamentals and application to gene and drug delivery. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007;9:415–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho CS, Ju LK, Ho CT. Measuring oxygen diffusion coefficients with polaro-graphic oxygen electrodes. II. Fermentation Media. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1986;28:1086–1092. doi: 10.1002/bit.260280720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ludwig A, Van Ooteghem M. Influence of the surface tension of eye drops on the retention of a tracer in the precorneal area of human eyes. J. Pharm. Belg. 1988;43:157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fan Z, Liu H, Mayer M, Deng CX. Spatiotemporally controlled single cell sonoporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:16486–16491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208198109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dayton PA, Morgan KE, Klibanov AL, Brandenburger G, Nightingale KR, Ferrara KW. A preliminary evaluation of the effects of primary and secondary radiation forces on acoustic contrast agents. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1997;44:1264–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palanchon P, Tortoli P, Bouakaz A, Versluis M, de Jong N. Optical observations of acoustical radiation force effects on individual air bubbles. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2005;52:104–110. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1397354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohl CD, Arora M, Ikink R, de Jong N, Versluis M, Delius M, Lohse D. Sonoporation from jetting cavitation bubbles. Biophys. J. 2006;91:4285–4295. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Postema M, Marmottant P, Lancee CT, Hilgenfeldt S, de Jong N. Ultrasound-induced microbubble coalescence. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2004;30:1337–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chomas JE, Dayton P, May D, Ferrara K. Threshold of fragmentation for ultrasonic contrast agents. J. Biomed. Opt. 2001;6:141–150. doi: 10.1117/1.1352752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faez T, Skachkov I, Versluis M, Kooiman K, de Jong N. In vivo characterization of ultrasound contrast agents: microbubble spectroscopy in a chicken embryo. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2012;38:1608–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Postema M, van Wamel A, Lancee CT, de Jong N. Ultrasound-induced encapsulated microbubble phenomena. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2004;30:827–840. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garbin V, Overvelde M, Dollet B, de Jong N, Lohse D, Versluis M. Unbinding of targeted ultrasound contrast agent microbubbles by secondary acoustic forces. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011;56:6161–6177. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/19/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frampton JP, Fan Z, Simon A, Chen D, Deng CX, Takayama S. Aqueous two-phase system patterning of microbubbles: localized induction of apoptosis in sonoporated cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013 accepted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zarnitsyn VG, Prausnitz MR. Physical parameters influencing optimization of ultrasound-mediated DNA transfection. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2004;30:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahim A, Taylor SL, Bush NL, ter Haar GR, Bamber JC, Porter CD. Physical parameters affecting ultrasound/microbubble-mediated gene delivery efficiency in vitro. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006;32:1269–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karshafian R, Bevan PD, Williams R, Samac S, Burns PN. Sonoporation by ultrasound-activated microbubble contrast agents: effect of acoustic exposure parameters on cell membrane permeability and cell viability. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2009;35:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Phillips LC, Klibanov AL, Wamhoff BR, Hossack JA. Targeted gene transfection from microbubbles into vascular smooth muscle cells using focused, ultrasound-mediated delivery. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2010;36:1470–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mehier-Humbert S, Bettinger T, Yan F, Guy RH. Ultrasound-mediated gene delivery: kinetics of plasmid internalization and gene expression. J. Control. Release. 2005;104:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Dosari MS, Gao X. Nonviral gene delivery: principle, limitations, and recent progress. AAPS J. 2009;11:671–681. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Escoffre JM, Teissie J, Rols MP. Gene transfer: how can the biological barriers be overcome? J. Membr. Biol. 2010;236:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamiya H, Fujimura Y, Matsuoka I, Harashima H. Visualization of intracellular trafficking of exogenous DNA delivered by cationic liposomes, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;298:591–597. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.