Abstract

Schwannoma affect mainly head, neck, and flexor aspect of the limbs. Neurogenic tumors arising from the brachial plexus are rare and axillary schwannoma is extremely uncommon. Cystic degeneration is common in longstanding cases and which when aspirated may yield only macrophages or lymphocytes leading to false diagnosis of the case in spite of strong clinical suspicion. We report one such rare case of a solitary axillary schwannoma with extensive cystic degeneration, which was misdiagnosed on fine needle aspiration cytology and subsequently confirmed by the histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry.

Keywords: Cystic degeneration, histopathological examination, immunohistochemistry, schwannoma

INTRODUCTION

Schwannoma are tumors arising from the embryonic neural crest cells of the nerve sheaths of peripheral and cranial nerves.[1] About 25% of the schwannoma occur in the head and neck region[2] involving cranial nerves and sympathetic chain; however, brachial plexus schwannoma are uncommon.[3] Degenerative changes such as hemorrhage, calcification, and fibrosis are commonly seen in the schwannoma, but cystic changes are rare.[4]

To the best of our knowledge, axillary schwannoma with such extensive cystic degeneration has not been reported so far. We report here, the first case of it diagnosed by the histopathological examination and confirmed with immunohistochemistry (IHC).

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old female presented to orthopedics-out-patient department with complaints of shoulder pain for 6 months and treated for cervical spondylitis, shoulder arthritis and given short wave diathermy and physiotherapy. The pain only worsened. In due course of treatment, she noticed an axillary mass, which increased gradually and further referred to surgery out-patient department for further management. Local examination revealed a 6 × 4 cm oval tender, firm, mobile mass in the left axilla deeper to pectoralis major muscle. A provisional diagnosis of peripheral nerve sheath tumor was made and the case was subjected for fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC).

Fine needle aspiration from the left axillary mass yielded 30 ml straw colored fluid. The size of the swelling markedly reduced after aspiration and no residual lump was palpated. The smears showed occasional lymphocytes in the proteinaceous background. The cytological diagnosis of benign cystic lesion possibly lymphatic cyst was made and the case was asked for biopsy.

Ultrasonogram showed a cystic lesion. On magnetic resonance imaging, a well-defined, oval shaped, hyperintense cystic lesion, of 6.6 × 4.8 cm in anterolateral compartment of arm was noted [Figure 1]. The lesion was parallel to long axis of neurovascular bundle predominantly in subcutaneous plane with an extension into the inter-muscular plane. The case underwent surgery and the excised mass was sent for the histopathological examination.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging scan showing hyperintense cystic lesion

Gross examination revealed a cystic mass measuring 6.5 × 4.5 × 2 cm. External surface was smooth and grey white. Cut section revealed uniloculated cyst filled with gelatinous material and the inner lining of the wall was smooth [Figure 2]. Sections from the cyst wall showed hypocellular and hypercellular areas. Hypercellular areas show spindle shaped cells having wavy nuclei arranged in fascicles with focal palisading of nuclei [Figure 3]. Hypocellular areas showed large number of foamy macrophages and loose myxoid stroma [Figure 4]. There was mild nuclear pleomorphism, but no mitotic activity was noted. On IHC tumor cells showed diffuse cytoplasmic positivity for S-100 protein [Figure 5] and was negative for KI67 [Figure 6]; confirming the diagnosis of schwannoma.

Figure 2.

Cut surface of the tumor showing cystic degeneration

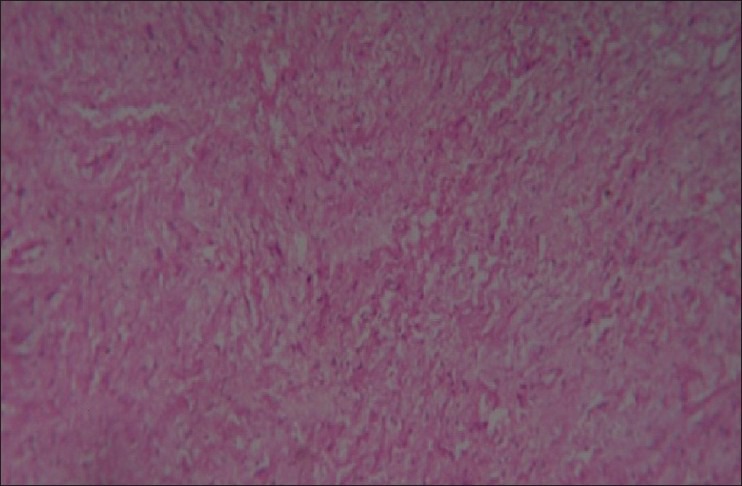

Figure 3.

Section showing hypocellular and hypercellular area (H and E, ×400)

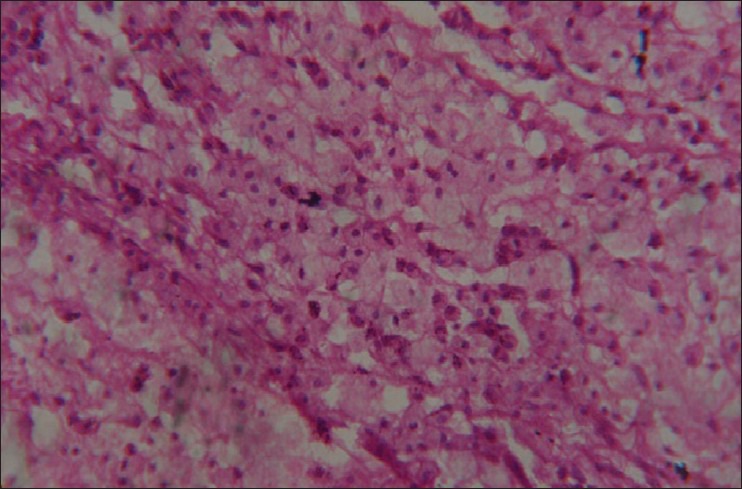

Figure 4.

Histological findings showing sheets of foamy macrophages (H and E, ×400)

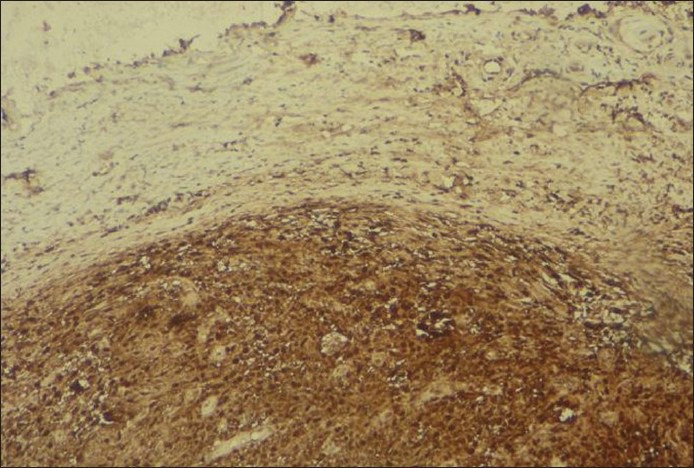

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry pictures showing cytoplasmic S-100 positivity (IHC, S-100, ×100)

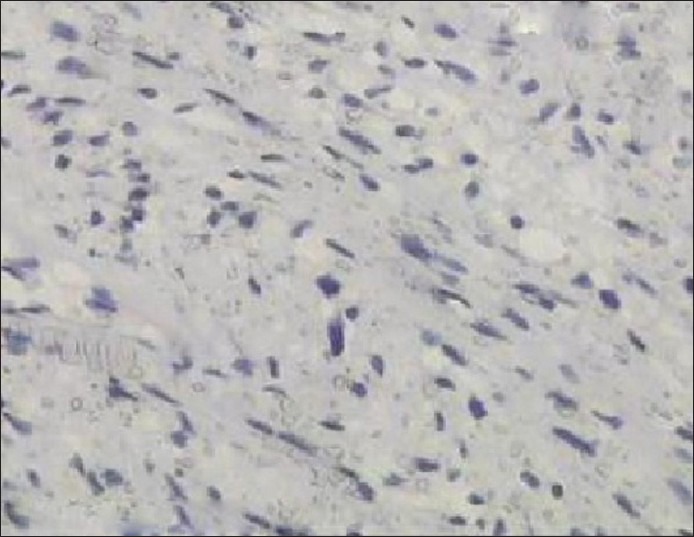

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showing KI67 negativity (IHC, KI67, ×100)

DISCUSSION

Schwannoma is a slow growing, solitary, firm, well-circumscribed and encapsulated round or ovoid tumors.[5] Extracranial schwannoma present as solitary mass anywhere in the body.[2] The common sites include the head and neck, the flexor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, the posterior mediastinum in the thorax and on the trunk.[2] Any part of the body can be affected mainly head and neck region, but localization in the axilla is very unusual.[3]

Ancient schwannoma was initially mentioned by Ackerman and Taylor[5] as a degenerative change occurring in a long standing schwannoma, was characterized by nuclear hyperchromasia, mild nuclear pleomorphism, stromal edema, fibrosis, and xanthomatous changes leading to a misdiagnosis of malignancy in the aspirates.

Grossly, schwannoma are usually solitary, well-circumscribed, firm, smooth surfaced tumors.[6] As extracranial schwannoma are usually large, these tumors manifest with secondary degenerative changes due to the long duration resulting in waxing and waning of the tumor size.[6] Schwannoma may demonstrate biphasic pattern with compact areas of high cellularity (Antoni type A) and loose, hypocellular myxoid areas with microcystic spaces (Antoni type B).[5]

Longstanding tumors may develop degenerative changes.[7] Degenerative changes such as hemorrhage, calcification, and fibrosis are commonly seen in schwannoma, but cystic changes are rare.[4] Degeneration is due to central tumor necrosis as the schwannoma grows to a size beyond the capacity of its blood supply.[6] The tumor as such may be infiltrated with large number of siderophages.[4] Such tumors have been reported in the orbital region,[7] tentorial hiatus,[8] posterior cavernous sinus,[8] and retroperitonium.[6] Axillary schwannoma reported by Nikumbh et al.[9] did not show cystic degeneration. Schwannoma with the cystic degeneration arising from the brachial plexus has been reported by Chen et al.,[10] but they found the focal solid area and the present case showed purely cystic tumor and did not reveal any solid area.

The differential diagnosis of such a large cyst in the axilla includes cystic schwannoma, ganglioma, and lymphangioma.[10] The tumor cells show cytoplasmic positivity for S-100 protein.[6] The diagnosis of the present case of schwannoma was established and possibility of ganglioma and lymphangioma was ruled out by the histopathological examination and IHC.

To conclude, schwannoma with extensive cystic degeneration should be considered as rare differential diagnosis of cystic lesion of the axilla. The histopathological examination remains the mainstay of differentiation as radio-imaging and FNAC features can be indistinguishable.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verocay J. Zur kenntnis der neurofibrome. Beitr Pathol Anat. 1910;48:1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ku HC, Yeh CW. Cervical schwannoma: A case report and eight years review. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:414–7. doi: 10.1258/0022215001905913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lusk MD, Kline DG, Garcia CA. Tumors of the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:439–53. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198710000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaiswal A, Shetty AP, Rajasekaran S. Giant cystic intradural schwannoma in the lumbosacral region: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2008;16:102–6. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackerman LV, Taylor FH. Neurogenous tumors within the thorax; A clinicopathological evaluation of forty-eight cases. Cancer. 1951;4:669–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195107)4:4<669::aid-cncr2820040405>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindler OS, Dixon JH, Case P. Retroperitoneal giant schwannomas: Report on two cases and review of the literature. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2002;10:77–84. doi: 10.1177/230949900201000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashyap S, Pushker N, Meel R, Sen S, Bajaj MS, Khuriajam N, et al. Orbital schwannoma with cystic degeneration. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37:293–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du R, Dhoot J, McDermott MW, Gupta N. Cystic schwannoma of the anterior tentorial hiatus. Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;38:167–73. doi: 10.1159/000069094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikumbh DB, Janugade HB, Mali RK, Madan PS, Wader JV. Axillary schwannoma: Diagnosed on fine needle aspiration cytology. Online J Health Allied Sci. 2011;10:20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen F, Miyahara R, Matsunaga Y, Koyama T. Schwannoma of the brachial plexus presenting as an enlarging cystic mass: Report of a case. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:311–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]