Abstract

We present autopsy findings of a case of limb body wall complex (LBWC). The fetus had encephalocele, genitourinary agenesis, skeletal anomalies and body wall defects. The rare finding in our case is the occurrence of both cranial and urogenital anomalies. The presence of complex anomalies in this fetus, supports embryonal dysplasia theory of pathogenesis for LBWC.

Keywords: Encephalocele, limb body wall anomaly, skeletal anomalies, urogenital agenesis

INTRODUCTION

Limb body wall complex (LBWC) is a rare complicated sporadic polymalformative fetal malformation syndrome, characterized by a wide spectrum of severe anomalies in the body wall. The incidence at birth is about 0.32 per 100,000 births because the majority of affected fetuses undergo intrauterine deaths.[1,2,3] Traditionally diagnosis has been based on the Van Allen et al.,[4] criteria, i.e. the presence of two out of three of the following anomalies (1) Exencephaly or encephalocele with facial clefts (2) Thoraco and or abdominoschisis and (3) Limb defects. We present a case of LBWC, which had overlapping phenotypic features, as it showed both encephalocele as well as renal tract agenesis. To the best of our knowledge this is the first case in literature exhibiting combined cranial and abdominal features.

CASE REPORT

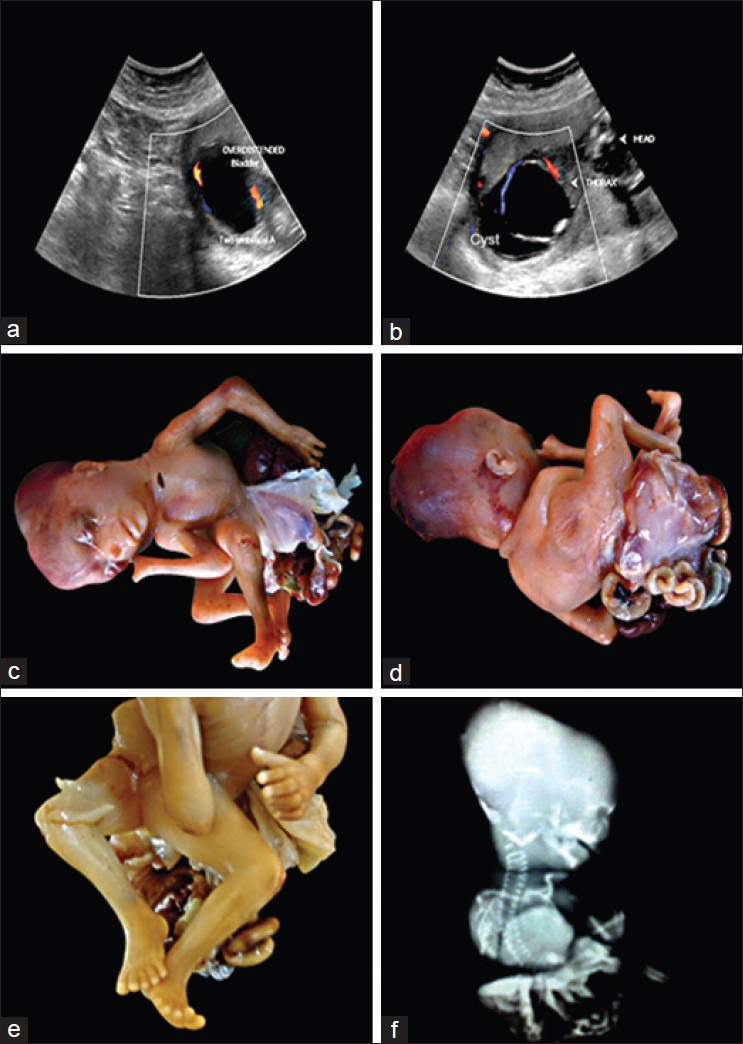

A 42-year-old, G3P2 L0 presented to the obstetrics outpatient department in the second trimester of her third pregnancy for a routine antenatal check up. She had two still births in the past, the details of which are not known. She is not a hypertensive or diabetic. There was no history of any drug intake except for iron and folic acid supplementation. Her routine hematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits. A routine anomalous scan done at 2nd trimester showed a fetus with features of intrauterine growth retardation along with a large fluid-filled sac in the abdominal region which was compressing the thorax. Both upper and lower extremities were visualized. However, due to oligohydraminos no further comment could be made upon the fetal anatomy. Color flow showed two umbilical arteries along the wall of the cyst. The intraabdominal unilocular cystic mass was assumed to be the urinary bladder and in conjunction with the presence of oligohydraminos and Intrauterine growth retardation a proposed diagnosis of congenital megacystitis or Prune Belly Syndrome was made [Figures 1a and 1b]. The parents were informed about the diagnosis and after counseling, they opted for termination of pregnancy. The pregnancy was terminated after obtaining the consent, and the abortus was sent for pathological examination.

Figure 1.

(a) Ultra sonograms showing a large cyst, in the wall of cyst umbilical vessels are seen (b) Ultra sonogram showing parts of fetus (note the large cyst in the lower part of the fetus) (c and d) Gross photograph of the fetus showing encephalocele, amelia of digits of right upper limb, abdominal wall defects with protrusion of organs which are covered by thin membrane, scoliosis and malrotation of the lower limbs (e) Closer view of lower limbs showing malrotation (lower limbs digits are arranged in opposite direction) (f) Infantogram showing encephalocele and scoliosis

At autopsy, the fetus weighed 75 g and on external examination a number of anomalies were noted. The genitalia were ambiguous. Encephalocoele was seen over the head of the fetus in the occipital region. The most striking abnormality was a left sided anterior abdominal wall defect, from which gastrointestinal organs were protruding. The organs identified included the liver and the intestine. Although these organs were not encased by a membrane, a membrane like structure was present near the anterior abdominal wall opening [Figures 1c and 1d]. A defect in the posterior abdominal wall was also noted. A number of skeletal abnormalities were noticed. There were scoliosis and amelia of the digits of the right upper limb. The lower limbs exhibited malrotation and were pushed to the right lateral side by the protruding abdominal organs [Figure 1e]. The umbilical cord was short and was found in a membrane like structure that was partially covering some of the protruding organs. A radiological examination was also done, which confirmed the gross skeletal anomalies and the encephalocele [Figure 1f]. On internal examination, there was agenesis of anal canal along with agenesis of genitourinary tract, and the lungs were hypoplastic. The remaining organs appeared normal on gross examination and congested on microscopy. In view of the above combination of malformations, a diagnosis of LBWC was offered.

DISCUSSION

LBWC was described for the first time by Van Allen et al.,[4] in 1987. It is also known by the other names like “Body stalk anomaly” “Congenital absence of umbilical cord” and “cyllosomus and Pleurosomus”.[3,5] The diagnostic criteria for LBWC is still debatable, the commonly used one was put forth by Van Allen et al., in1987 as stated earlier. Russo et al.,[6] in 1993 identified two distinct phenotypes Type I (craniofacial defects, facial clefts, amniotic adhesions and amniotic band syndrome) and Type II (No craniofacial defects, Urogenital anomalies, imperforate anus, lumbosacral meningomyelocele, severe kyphoscolosis and placental anomalies). The sole criteria used by Russo et al.,[6] was craniofacial defects in Type I and many other thorasic and abdominal anomalies in Type II. To overcome this deficiency Sahinoglu et al.,[7] in 2007 proposed a new classification: Type I (Fetus has craniofacial defect and intact thoracoabdominal wall, often normal placenta and umbilical cord but rarely attached to the malformated cranial structures), Type II (Fetus has supraumbilical, usually laterally located (often left side) large thoracoabdominal wall defect. Eventrated abdominal organs enveloped within the amniotic sheet connects to the skin margin of the wall defect. No well-formed umbilical cord and usually normal cloacal structures are detected). Type III (Fetus has infraumbilical abdominal wall defect with intact thorax. The placenta is attached broadly to the skin at the site of defect. The abdominal organs are eventrated into the extraembryonic coelomic cavity. The cloacal structures are almost always malformed or absent). Our case obeyed Van Allen criteria and was distinct from the fetuses observed by Russo et al.,[6] and Sahinoglu et al.,[7]

The exact etiology of this condition is still unclear, Tropin's amniotic band theory and Van Allen's vascular theory failed to explain all the anomalies observed in LBWC.[4,8] The most accepted theory is early embryonal dysplasia put forward by Hartwig et al.,[9] in 1989. According to this, there will be an abnormal embryonic folding related to malfunctioning of the body wall ectodermal placode. This leads to defective closure of embryonic abdominal wall, umbilical abnormality and persistence of extra embryonic coelom communicating with the abdominal cavity. These ectodermal placodes also add cells to mesoderm of the trilaminar embryonic disc, which is destined to form the genitourinary tract. Some authors suggest that vascular disruption is secondary to hypoplasia of the blood vessel in the affected area rather than being the primary etiological factor.[7] The complex anomalies observed in our case can be explained by embryonal folding theory. This anomaly does not have any sex predilection and recurrence of this condition is observed in two families suggesting a possible genetic etiology.[10]

LBWC is a heterogeneous disease and is associated with varied internal anomalies. The central nervous system anomalies observed are, anencephaly, encephalocele and alobar holoprosencephaly. Cardiovascular anomalies include primitive ventricle, common atrium, atrial septal defects, truncus arteriosus, membranous Ventricular septal defects hypoplastic right ventricle and ectopic cardis. The renal anomalies observed are unilateral or bilateral aplasia/hypoplasia of kidney, hydronephrosis, renal dysplasia, polycystic kidney and calcification of kidney. Genital abnormalities seen are abnormal external genitalia, absent gonad and extrophy of bladder. Skeletal anomalies are most common and include club foot, oligodactyly, arthrogryposis, absent limb, single forearm bone, single lower leg bone, pesudosyndactyly, radial/ulnar hypoplasia, rotational defects and polydactyly. Other anomalies include trilobulated liver, polysplenia, absent gall bladder, amniotic bands and single umbilical artery. We have observed complex cranial and abdominal anomalies which are not observed in the literature.[3,5,11]

The diagnosis of this condition can be established by measuring maternal serum alpha feto protein level. Prenatal ultrasound examination (USG) can detect this anomaly as early as first trimester. The USG findings of this anomaly are the presence of abdominal wall defects along with kyphoscoliosis and limb abnormality. LBWC is a lethal anomaly hence it has to be differentiated from treatable causes like omphalocele or gastroschisis, but sometimes oligohydramnios may mask the underlying anomalies and therefore, challenge the radiologist. For the diagnosis of this syndrome necropsy is the gold standard. Karyotyping is usually normal. Early diagnosis followed by medical termination is the preferred treatment for this anomaly.[3]

CONCLUSION

LBWC is a lethal polymalformative fetal malformation syndrome. A rare combination of cranial and abdominal anomalies is presented, and our case supported the embryonal dysplasia theory of pathogenesis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.D’souza J, Indrajit IK, Menon S. Limb body wall complex. Med J Armed Forces India. 2004;60:77–80. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasun P, Behera BK, Pradhan M. Limb body wall complex. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:255–6. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.41674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borade A, Prabhu AS, Prabhu GS, Prabhu SR. Limb Body Wall Complex (LBWC) [Last cited on 2009 Jul 1];Pediatric Oncall. 2009 6 Art # 37. Available from: http://www.pediatriconcall.com/fordoctor/casereports/limb.asp . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Allen MI, Curry C, Gallagher L. Limb body wall complex: I. Pathogenesis. Am J Med Genet. 1987;28:529–48. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Managoli S, Chaturvedi P, Vilhekar KY, Gagane N. Limb body wall complex. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:891–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo R, D’Armiento M, Angrisani P, Vecchione R. Limb body wall complex: A critical review and a nosological proposal. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47:893–900. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahinoglu Z, Uludogan M, Arik H, Aydin A, Kucukbas M, Bilgic R, et al. Prenatal ultrasonographical features of limb body wall complex: A review of etiopathogenesis and a new classification. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2007;26:135–51. doi: 10.1080/15513810701563728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torpin R. Amniochorionic mesoblastic fibrous strings and amnionic bands: Associated constricting fetal malformations or fetal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;91:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(65)90588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartwig NG, Vermeij-Keers C, De Vries HE, Kagie M, Kragt H. Limb body wall malformation complex: An embryologic etiology? Hum Pathol. 1989;20:1071–7. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plakkal N, John J, Jacob SE, Chithira J, Sampath S. Limb body wall complex in a still born fetus: A case report. Cases J. 2008;1:86. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socolov D, Terinte C, Gorduza V, Socolov R, Puiu JM. Limb body wall complex-case presentation and literature review. Rom J Leg Med. 2009;17:133–8. [Google Scholar]