Abstract

Statistical learning is a rapid and robust mechanism that enables adults and infants to extract patterns of stimulation embedded in both language and visual domains. Importantly, statistical learning operates implicitly, without instruction, through mere exposure to a set of input stimuli. However, much of what learners must acquire about a structured domain consists of principles or rules that can be applied to novel inputs. Although it has been claimed that statistical learning and rule learning are separate mechanisms, here we review evidence and provide a unifying perspective that argues for a single mechanism of statistical learning that accounts for both the learning of the input stimuli and the generalization to novel instances. The balance between instance-learning and generalization is based on two factors: the strength of perceptual biases that highlight structural regularities, and the consistency of unique versus overlapping contexts in the input.

Keywords: statistical learning, rule learning, generalization, infants

Imagine it's your 10th birthday and your parents have given you a new videogame. But the instructions are missing. Surely you can figure it out. You flip on the power switch and a stream of sounds comes out of a loudspeaker and a cascade of pictures moves across the display screen. The flow of information is overwhelming. What should you attend to – the sounds or the pictures? Is it the quality of the sounds or their ordering in time that matters? Is it the identity of the objects in the pictures or their specific shapes and colors that matter?

The foregoing scenario is not unlike the world confronting a naïve learner. There is structure in the world, we presume, and some set of principles that describes that structure. We can't possibly learn that structure without gathering some input, yet we can't wait for every potential structure to be available before making inferences about the “rules of the game”. But there is an infinitely large set of structures that could be embedded in the input. In a videogame, the sound presented when an alien appears on the screen could predict whether the alien will attack or flee. Similarly, in the natural environment, a child learning the names of objects must confront the ambiguity of what a word means – does “doggie” refer to a type of animal, the color brown, the furry coat, or having four legs?

Statistical learning in language and vision

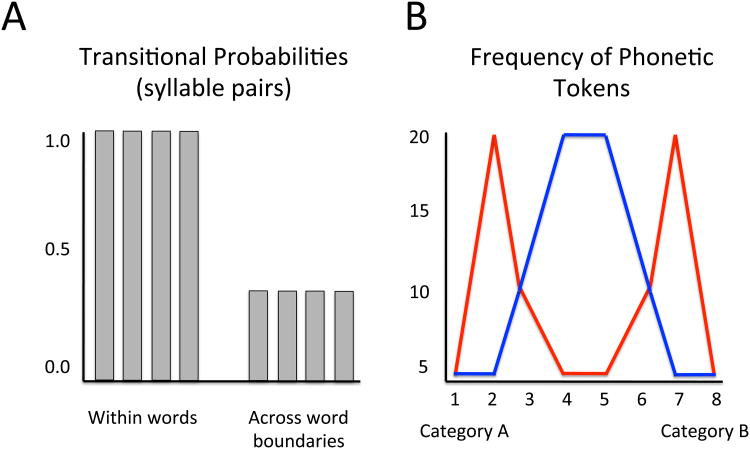

The problem is that the learner must select the correct structure from an infinite number of potential structures present in any set of data, without waiting forever and without the aid of an instructor who provides an explanation of the operating principles (Chomsky, 1965). Somewhat surprisingly, adults and even infants are quite good at this task of extracting the organizational structure of a set of seemingly ambiguous data by merely observing (or listening to) the input. An early demonstration of this powerful learning mechanism was reported by Saffran, Aslin, and Newport (1996). They asked whether 8-month-old infants could discover the “words” in a stream of speech when all sources of information – except the probability that certain syllables followed each other in immediate succession – were absent. The infants heard a continuous stream of speech sounds comprised of 4 randomly ordered 3-syllable words, with no pauses between the words and no pitch or duration cues to signal the location of word boundaries (see Figure 1). What defined a word, therefore, was the fact that, within a word, each syllable was always followed by only one other syllable, whereas the last syllable of each word was followed by a number of other possible syllables (the first syllable of any of the other words).

Figure 1.

The design of Saffran, Aslin, and Newport (1996).

Thus, the transitional probability from one syllable to another within a word was 1.0, whereas the transitional probability of syllable pairs at word boundaries was 0.33. Infants demonstrated their ability to learn which syllables grouped together to form the words by responding differently in a post-exposure test to words versus part-words. After only two minutes of listening to a continuous stream of syllables, in which the presence and number of the words and the location of these words in the speech stream were unknown to the infant, they recognized the words – that is, they managed to discover the correct underlying structure by mere exposure.

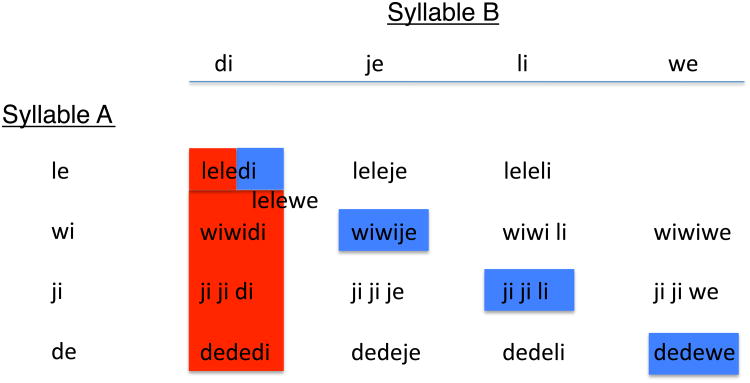

Saffran et al. (1996) suggested the term statistical learning to describe the process by which learners acquire information about distributions of elements. In their experiment, the elements were the syllables and the distributions were how often these elements occurred in relation to one another (see Figure 2A). The frequency of syllables was equated, so this couldn't be the statistic learners were using to do word segmentation. But another statistic, one that could distinguish words from other sequences of syllables in the stream of speech, was the transitional probability from one syllable to the next. If learners could keep track of this statistic for every pair of syllables in the stream, then they would be able to discriminate between words and part-words. The results of the Saffran et al. study suggested that indeed learners were computing such a statistic (though without being aware of performing such a computation).

Figure 2.

Distributions of (A) transitional probabilities (from Saffran et al., 1996) and (B) phonetic tokens (from Maye et al., 2002). The blue distribution in (B) is unimodal and the red distribution is bimodal.

Another example of statistical learning comes from the domain of speech perception. Maye and colleagues (Maye, Werker & Gerken, 2002; Maye, Weiss & Aslin, 2008) presented infants with syllables that came from a continuum spanning two phonetic categories (see Figure 2B). When the frequencies of the various syllables in the exposure formed a unimodal distribution, infants did not discriminate the difference between the categories, but when the syllables formed a bimodal distribution, discrimination was reliable. Thus, as in Saffran et al. (1996), infants can extract a statistic (in this case, syllable frequencies) from a corpus of speech to make implicit decisions about a test stimulus that came from that corpus.

Subsequent experiments have shown that these remarkable statistical learning abilities are not limited to language. Kirkham, Slemmer, and Johnson (2002) reported that infants as young as 2 months of age, after exposure to a temporal sequence of visual shapes, could discriminate between familiar and novel shape-sequences. Fiser and Aslin (2002) showed that 9-month-old infants could learn the statistical consistency with which shapes were spatially arranged in visual scenes. And recent studies have documented statistical learning in newborns, for both auditory (Teinonen, Fellman, Naatanen, Alku & Huotilainen, 2009) and visual stimuli (Bulf, Johnson &Valenza, 2011). Thus, statistical learning is a powerful and domain-general mechanism available early in development to infants who are naïve (i.e., uninstructed) about how to negotiate a complex learning task.

These results show that a statistical learning mechanism enables learners to extract one or more statistics and use this information to make an implicit decision about the stimulus materials that were present in the input. This is important for learning which syllables form words, for estimating the number of peaks in a distribution of speech sounds, or for discovering which visual features form the parts of a scene. But this does not address the question of forming rules – abstractions about patterns that could be generalized to elements that have never been seen or heard. How do learners who are exposed to a subset of the possible patterns in their input go beyond this to infer a set of general principles or “rules of the game”?

From statistical learning to rule learning

Several studies have documented that infants can make the inductive leap from observed stimuli to novel stimuli that follow the same rules. Gomez and Gerken (1999) presented 12-month-olds with short sentences made up of nonsense words. These words formed categories, like nouns and verbs, and infants showed evidence of learning that a grammatical noun-verb pair that was not present in the exposure stimuli, but was composed of familiar words following the grammatical pattern, was nevertheless “familiar”.

Marcus, Vijayan, BandiRao, and Vishton (1999) went even farther. They showed that 7-month-olds who listened to 3-word sentences containing a repeating word in either the first two or the last two positions (i.e., AAB or ABB) were able to apply that repetition rule to completely novel words. As in the case of statistical learning, this AAB or ABB repetition learning is not limited to language stimuli but also applies to visual stimuli and to musical sequences (Dawson & Gerken, 2009; Johnson, Fernandes, Frank, Kirkham, Marcus, Rabagliati, & Slemmer, 2009; Marcus, Fernandes & Johnson, 2007; Saffran, Pollak, Seibel, & Shkolnik, 2007).

Some researchers have claimed that statistical learning and rule learning are two separate mechanisms because statistical learning involves learning about elements that have been presented during exposure, whereas rule learning can be applied to novel elements and novel combinations (see Marcus, 2000; Endress & Bonatti, 2007). But why do learners sometimes keep track of the specific elements in the input they are exposed to and at other times learn a rule that extends beyond the specifics of the input? An alternate hypothesis is that these two processes are in fact not distinct, but rather are different outcomes of the same learning mechanism.

For example, some stimulus dimensions are just naturally more salient than others. If stimuli are encoded in terms of their salient dimensions rather than in terms of their specific details, then learners will appear to generalize by applying what they have learned to all stimuli that exhibit the same pattern on these salient dimensions. Returning to our 10-year-old and the instruction-less videogame, as sounds are playing and objects are flying by on the screen, it may be extremely difficult to remember the specific sounds or object-shapes, but you know immediately that all the sounds are high pitched (or not) and all the objects are falling (or not). These highly salient dimensions constrain the way in which the learner encodes the potential structure in the input, dramatically reducing the ambiguity about what the learner should attend to. And if high-pitched sounds predict a hostile invader and falling objects provide protection, the learner can quickly induce the rules that enable longevity in the game.

Salient perceptual dimensions can also constrain the statistical patterns that learners most readily acquire. Temporal proximity is a powerful constraint: learners rapidly acquire the statistical patterns among elements that immediately follow each other. Moreover, infants are particularly attentive to the immediate repetition of a stimulus (Marcus, et al., 1999), even as young as 1-2 days of age (Gervain, Macagno, Cogoi, Pena, & Mehler, 2008). However, temporal proximity does not always dominate learning. Adults automatically attend to the musical octave of a sequence of tones, and this (more than temporal proximity) can constrain how they learn the statistical relationships between tones. Melodic patterns among tones in the same octave are learned, even if they do not immediately follow one another, whereas melodic patterns among interleaved and adjacent tones in different octaves are not acquired (Creel, Newport, & Aslin, 2004; Dawson & Gerken, 2009). More generally, Gestalt principles of perceptual grouping (such as temporal proximity and perceptual similarity) serve as important constraints on the element groupings within which statistical regularities are most readily learned (Creel, Newport & Aslin, 2004; Endress, Nespor & Mehler, 2009). These constraints influence whether adults learn statistical regularities among elements that are temporally adjacent or that span an intervening element (Gebhart, Newport & Aslin, 2009; Newport & Aslin, 2004).

Rule learning without perceptual cues

Although perceptual cues can serve as powerful constraints on statistical learning, perceptual salience is not how most rules are defined in the natural environment. For example, all chairs have some perceptual similarity, but it is the function of a chair, not its form, that defines it. Similarly, in language, verbs do not sound alike, and they do not sound consistently different from nouns. What allows a naïve learner to induce a general rule, one that applies to a set of elements rather than just one instance, when it has no perceptual basis? One possibility is that learners are sensitive to contexts that signal this important distinction: they acquire rules when the patterns in the input indicate that several elements occur interchangeably in the same contexts, but they acquire specific instances when the patterns apply only to the individual elements. For example, Xu and Tenenbaum (2007) have shown that, if children hear the word “glim” applied to three different dogs, then they infer that “glim” means dog. In contrast, if “glim” is used three times for the same dog, they interpret it as the dog's name. The same contrast between learning items and learning rules can occur for syllable and word sequences as well.

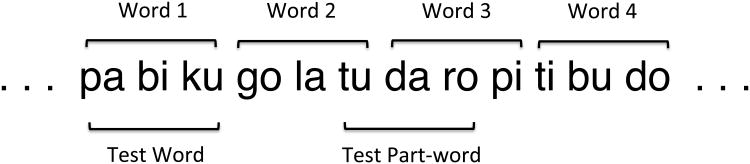

Gerken (2006) has made this argument by re-considering the design of the Marcus et al. (1999) rule-learning experiment (see Figure 3). In Marcus et al. (1999) there were 16 different AAB strings presented in the learning phase of the experiment. Focusing on the final syllable, 4 strings ended in di, 4 ended in je, 4 ended in li, and 4 ended in we. What determines when infants will learn the general rule AAB, and when they will learn a more specific pattern: that every string ends in di, je, li, or we? The more consistent or reliable cue was the “repetition of the first two syllables” – the AAB rule – because it applied to every string, whereas the “ends in di” or “ends in je” rule applied only to one-fourth of the strings. Gerken (2006) tested this hypothesis by presenting infants with a subset of the 16 strings from the Marcus et al. (1999) study. Infants who heard only four AAB strings that all ended in the same syllable (e.g., di in the leftmost column of Figure 3) were tested on two equally plausible rules: (1) all strings involve an AAB repetition, and (2) all strings end in di. These infants failed to generalize to a novel string that retained the AAB pattern but did not end in di. In contrast, infants who heard only four AAB strings lying along the diagonal in Figure 3 replicated the Marcus et al. result. Because each of these strings had an AAB pattern and ended in four different syllables, only the AAB rule was reliable.

Figure 3.

The design of Marcus et al. (1999) and the two sets of 4 words (red column and blue diagonal) used by Gerken (2006).

Reeder, Newport, and Aslin, (2009, 2010) have shown a similar phenomenon – and described some of the principles for its operation – in the learning of an artificial language grammar. In these experiments, adult learners were presented with sentences made up of nonsense words that came from different grammatical categories A, X, and B, much like subjects, verbs, and direct objects in sentences such as “Bill ate lunch”. Depending on the experiment, the input included sentences in which all of the words within a particular category occurred in the same contexts (e.g., words X1, X2, and X3 all occur after any of the A words and before any of the B words), or it only included sentences in which the X-words appeared in a limited number of overlapping A-word or B-word contexts. Adult learners are surprisingly sensitive to these differences. Their tendency to generalize depends on the precise degree of overlap among word contexts that they have heard in the input, and also on the consistency with which a particular A or B word is missing from possible X-word contexts. Adults generalize rules when the shared contexts are largely the same, with only an occasional absence of overlap (i.e., a “gap”). However, when the gaps are persistent, they judge them to be legitimate “exceptions to the rule” and no longer generalize to these novel contexts. Thus, similar to Gerken (2006), it is the consistency of the context cues that leads learners to generalize to novel strings, and it is the inconsistency of context cues that leads learners to withhold generalization and treat some strings as exceptions.

The key point here is that statistical learning and rule learning are not, from the perspective of the reliability of context cues, different mechanisms (see Orban, Fiser, Aslin, & Lengyel, 2008). When there are strong perceptual cues, such as the repetition of elements in an AAB sequence, a statistical learning mechanism can compute regularities of the repetitions (i.e., they are either present or absent) or of the elements themselves (the particular syllables). And in Gerken (2006) and Reeder et al. (2009, 2010), even when there are no perceptual cues, it is the consistency of how the context cues are distributed across strings of input that determines whether a rule is formed – enabling generalization to novel strings – or whether specific instances are learned. According to this hypothesis, statistical learning is a single mechanism whose outcome either applies to elements that have been experienced or to generalization beyond experienced elements, depending on the manner and consistency with which elements pattern themselves in the learner's input. Importantly, this balance of learning is accomplished without instruction, from merely being exposed to structured input.

Language universals and statistical learning

Perceptual salience and the patterning of context cues are not the only factors that can influence what learners acquire using a statistical learning mechanism. An extensive literature in linguistics has argued that languages of the world display a small number of universal patterns – or a few highly common patterns, out of many that are possible – and has suggested that language learners will fail to acquire languages that do not exhibit these regularities (Chomsky, 1965, 1995; Croft, 2002; Greenberg, 1963). Recently a number of studies using artificial grammars have indeed shown that both children and adults will more readily acquire languages that observe the universal or more typologically common patterns attested in natural languages.

For example, Hudson Kam & Newport (2005, 2009) and Austin & Newport (2011) have studied adults and children presented with miniature languages containing inconsistent, probabilistically occurring forms (e.g., a nonsense word ka follows nouns 67% of the time, whereas po occurs in the same position the remaining 33% of the time). This type of probabilistic variation is not characteristic of natural languages, but it does occur in the speech of non-native speakers who make grammatical errors. Adult learners match the probabilistic variation they hear in their input when they speak sentences using the miniature language, but young children form a regular rule, producing ka virtually all the time, thereby restoring to the language the type of regularity that is more characteristic of natural languages.

In other artificial language studies (Culbertson & Legendre, 2010; Culbertson, Smolensky & Legendre, 2011; Fedzechkina, Jaeger & Newport, 2011; Finley & Badecker, 2009; Tily, Frank & Jaeger, 2011), even adult learners will preferentially learn languages that follow universal linguistic patterns and will often alter the languages to be more in line with these universals. In adult learners these alterations are very small, but such changes can accumulate over generations of learners, shifting languages gradually through time (Tily, Frank & Jaeger, 2011).

It is not always clear why learners acquire certain types of patterns more easily than others (and therefore why languages more commonly exhibit these patterns). Some word orders place prominent words in more consistent positions across different types of phrases; other patterns are more internally regular or conform better to the left-to-right biases of auditory processing. A full understanding of the principles underlying these learning outcomes awaits further research. What is clear, however, is that statistical learning is not simply a veridical reproduction of the stimulus input; learning is shaped by a number of perceptual and memory constraints, at least some of which may apply not only to languages but also to nonlinguistic patterns.

Summary and Future directions

Studies of statistical learning have revealed a remarkably robust mechanism that extracts distributional information in different domains and across development. There remain two fundamental challenges for the future: (1) to provide a comprehensive theory of the statistical computations that suffice to explain such learning, and (2) to understand the neural mechanisms that support statistical learning and how these mechanisms change over development or remain invariant (see Abla, Katahira & Okanoya, 2008; Abla & Okanoya, 2008; Friederici, Bahlmann, Helm, Schubotz, & Anwander, 2006; Gervain et al. , 2008; Karuza, Newport, Aslin, Davis, Tivarus & Bavelier, 2011; McNealy, Mazziotta, & Dapretto, 2006, 2010; Tienonen et al., 2009; Turk-Browne, Scholl, Chun, & Johnson, 2009).

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported, in part, by NIH grants HD-37082 and DC-00167.

References

- Abla D, Katahira K, Okanoya K. On-line assessment of statistical learning by event-related potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:952–964. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abla D, Okanoya K. Statistical segmentation of tone sequences activates the left inferior frontal cortex: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2787–2795. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Newport EL. When children learn more than they are taught: Regularization in child and adult learners. Manuscript under review 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Bulf H, Johnson SP, Valenza E. Visual statistical learning in the newborn infant. Cognition. 2011;121:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. The minimalist program. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Creel SC, Newport EL, Aslin RN. Distant melodies: Statistical learning of non-adjacent dependencies in tone sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;30:1119–1130. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft W. Typology and universals. In: Aronoff M, Rees-Miller J, editors. The Blackwell Handbook of Linguistics. 2nd. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson J, Legendre G. Investigating the evolution of agreement systems using an artificial language learning paradigm; Proceedings of the Western Conference on Linguistics; 2010.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson J, Smolensky P, Legendre G. Learning biases predict a word order universal. Manuscript under review. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson C, Gerken LA. From domain-generality to domain-sensitivity: 4-Month-olds learn an abstract repetition rule in music that 7-month-olds do not. Cognition. 2009;111:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endress AD, Bonatti LL. Rapid learning of syllable classes from a perceptually continuous speech stream. Cognition. 2007;105:247–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endress AD, Nespor M, Mehler J. Perceptual and memory constraints on language acquisition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedzechkina M, Jaeger T, Newport E. In: Carlson L, Hölscher C, Shipley T, editors. Functional biases in language learning: Evidence from word order and case-marking interaction; Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Austin, TX. Cognitive Science Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Finley S, Badecker W. Vowel harmony and feature-based representations. Journal of Memory and Language. 2009;61:423–437. [Google Scholar]

- Fiser J, Aslin RN. Statistical learning of new visual feature combinations by infants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:15822–15826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232472899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD, Bahlmann J, Helm S, Schubotz RI, Anwander A. The brain differentiates human and non-human grammars: Functional localization and structural connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:2458–2463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509389103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart AL, Newport EL, Aslin RN. Statistical learning of adjacent and non-adjacent dependencies among non-linguistic sounds. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:486–490. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.3.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken LA. Decisions, decisions: Infant language learning when multiple generalizations are possible. Cognition. 2006;98:B67–B74. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervain J, Macagno F, Cogoi S, Pena M, Mehler M. The neonate brain detects speech structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:14222–14227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806530105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez RL, Gerken LA. Artificial grammar learning by one-year-olds leads to specific and abstract knowledge. Cognition. 1999;70:109–135. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J. Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In: Greenberg J, editor. Universals of language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1963. pp. 73–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson Kam CL, Newport EL. Regularizing unpredictable variation: The roles of adult and child learners in language formation and change. Language Learning and Development. 2005;1:151–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson Kam CL, Newport EL. Getting it right by getting it wrong: When learners change languages. Cognitive Psychology. 2009;59:30–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SP, Fernandes KJ, Frank MC, Kirkham NZ, Marcus GF, Rabagliati H, Slemmer JA. Abstract rule learning for visual sequences in 8- and 11-month-olds. Infancy. 2009;14:2–18. doi: 10.1080/15250000802569611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuza E, Newport EL, Aslin RN, Davis S, Tivarus M, Bavelier D. Neural correlates of statistical learning in a word segmentation task: An fMRI study. Neurobiology of Language Conference; Annapolis, MD. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham NZ, Slemmer JA, Johnson SP. Visual statistical learning in infancy: Evidence for a domain general learning mechanism. Cognition. 2002;83:B35–B42. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GF. Pabiku and Ga Ti Ga: Two mechanisms infants use to learn about the world. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9:145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GF, Fernandes KJ, Johnson SP. Infant rule learning facilitated by speech. Psychological Science. 2007;18:387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GF, Vijayan S, BandiRao S, Vishton PM. Rule learning in 7-month-old infants. Science. 1999;283:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maye J, Werker JF, Gerken L. Infant sensitivity to distributional information can affect phonetic discrimination. Cognition. 2002;82:B101–B111. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(01)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maye J, Weiss DJ, Aslin RN. Statistical phonetic learning in infants: Facilitation and feature generalization. Developmental Science. 2008;11:122–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNealy K, Mazziotta JC, Dapretto M. Cracking the language code: Neural mechanisms underlying speech parsing. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:7629–7639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5501-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNealy K, Mazziotta JC, Dapretto M. The neural basis of speech parsing in children and adults. Developmental Science. 2010;13:385–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport EL, Aslin RN. Learning at a distance: I. Statistical learning of non-adjacent dependencies. Cognitive Psychology. 2004;48:127–162. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0285(03)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orban G, Fiser J, Aslin RN, Lengyel M. Bayesian learning of visual chunks by human observers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:2745–2750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708424105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder PA, Newport EL, Aslin RN. In: Taatgen N, van Rijn H, editors. The role of distributional information in linguistic category formation; Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society; Austin TX. Cognitive Science Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reeder PA, Newport EL, Aslin RN. In: Ohlsson S, Catrambone R, editors. Novel words in novel contexts: The role of distributional information in form-class category learning; Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Austin, TX. Cognitive Science Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saffran JR, Aslin RN, Newport EL. Statistical learning by 8-month-old infants. Science. 1996;274:1926–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffran JR, Pollak SD, Seibel RL, Shkolnik AA. Dog is a dog is a dog: Infant rule learning is not specific to language. Cognition. 2007;105:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teinonen T, Fellman V, Naatanen R, Alku P, Huotilainen M. Statistical language learning in neonates revealed by event-related brain potentials. BMC Neuroscience. 2009;10:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tily H, Frank MC, Jaeger TF. In: Carlson L, Hölscher C, Shipley T, editors. The learnability of constructed languages reflects typological patterns; Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Austin, TX. Cognitive Science Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Turk-Browne NB, Scholl BJ, Chun MM, Johnson MK. Neural evidence of statistical learning: Efficient detection of visual regularities without awareness. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21:1934–1945. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Tenenbaum JB. Word learning as Bayesian inference. Psychological Review. 2007;114:245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Recommended Readings

- Aslin RN, Newport EL. What statistical learning can and can't tell us about language acquisition. In: Colombo J, McCardle P, Freund L, editors. Infant pathways to language: Methods, models, and research directions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baker MC. The Atoms of Language: The Mind's Hidden Rules of Grammar. New York: Basic Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gerken LA. Infants use rational decision criteria for choosing among models of their input. Cognition. 2010;115:362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervain J, Mehler J. Speech perception and language acquisition in the first year of life. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:191–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JF, Pelucchi B, Graf Estes K, Saffran JR. Linking sounds to meanings: Infant statistical learning in a natural language. Cognitive Psychology. 2011;63:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SP. How infants learn about the visual world. Cognitive Science. 2010;34:1158–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]