Abstract

Research Findings

The current project examined the unique and interactive relations of child effortful control and teacher–child relationships to low-income preschoolers’ socioemotional adjustment. One hundred and forty Head Start children (77 boys and 63 girls), their parents, lead teachers, and teacher assistants participated in this study. Parents provided information on child effortful control, whereas lead teachers provided information on their relationships with students. Teacher assistants provided information on children's socioemotional adjustment (emotional symptoms, peer problems, conduct problems, prosocial behaviors) in the preschool classroom. Both teacher–child closeness and conflict were significantly related to low-income preschoolers’ socioemotional adjustment (i.e., emotional symptoms, peer problems, conduct problems, and prosocial behaviors) in expected directions. In addition, teacher–child conflict was significantly associated with emotional symptoms and peer problems among children with low effortful control; however, teacher–child conflict was not significantly associated with socioemotional difficulties among children with high effortful control. Teacher–child closeness, on the other hand, was associated with fewer socioemotional difficulties regardless of children's level of effortful control.

Practice or Policy

Results are discussed in terms of (a) the utility of intervention efforts focusing on promoting positive teacher–child interactions and enhancing child self-regulatory abilities and (b) the implications for children's socioemotional adjustment.

Children from low-income families begin life at a higher risk for social and developmental problems because of disproportionate exposure to adverse conditions such as lack of access to health care, stressful home environments, and residential instability, all of which have been associated with poorer social, behavioral, and academic outcomes (Felner, Brand, DuBois, Adan, Mulhall, & Evans, 1995; Xue, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2005). Head Start children in particular are at a higher risk for developing social and behavioral problems because the aforementioned risk factors are proportionally higher among low-income families than socioeconomically advantaged families (McLoyd, 1990; Webster-Stratton, 1998). Although individual differences in factors such as parenting, nutrition, and health conditions have been explored in relation to low-income children's development, these factors alone have not been shown to fully explain socioemotional difficulties among children in poverty, which include high incidences of conduct problems and social difficulties (Eamon, 2001; Webster-Stratton, 1998).

Many interventions have emphasized how examining child factors, such as emotion/behavior regulatory abilities, in combination with socioeconomic (poverty) and environmental stressors (i.e., poor parent and teacher–child relations, negative parenting, school problems, and neighborhood danger) may reveal the mechanisms by which these factors influence children's socioemotional development (McClowry, 1998). Evidence supporting individual differences in children's abilities and indications that controlling for socioeconomic status is not enough to explain variations children's school outcomes highlight the need to examine both dispositional (i.e., child temperament) and contextual (i.e., teacher–child relationships) influences on low-income children's socioemotional adjustment (Sirin, 2005). However, few studies to date have examined how the combination of these factors is related to children's socioemotional and behavioral adaptation during early childhood.

The increasing focus on school readiness, which encompasses children's ability to competently explore their environment and form trusting relationships with adults, intuitively lends itself to examining how child temperament and teacher–child relationships are related to young children's socioemotional adjustment. Understanding the interaction of child characteristics and teacher behaviors is beneficial for promoting both positive classroom environments and positive child outcomes because understanding how temperament can affect behavior in early childhood can shift thoughts from children's purposeful misbehavior to a focus on active problem solving in regard to children's individual differences (Rothbart & Jones, 1998). For example, when a child engages in disruptive behaviors, teachers must make instant attributions about the reasons for the behaviors and decide how to respond (Keogh, 2003; Rothbart & Jones, 1998). Thus, when the child's characteristics and behaviors do not meet teachers’ expectations for acceptable behaviors, how teachers respond to those characteristics and behaviors can set the course of positive versus negative teacher–child interactions (Myers & Pianta, 2008). In addition, given that perceptions of children can vary by teacher and that outcomes will vary even for children who experience similar situations, it is also possible that children's temperamental characteristics can influence how these children experience the same teacher behaviors (Morris et al., 2002). For instance, negative teacher–child interactions may be particularly harmful among children with temperamental vulnerabilities and may have a lesser impact on children whose temperamental characteristics leave them more resilient when involved in these negative exchanges.

The challenge for early childhood researchers is to identify factors that can affect how children respond to interactions with teachers and to include these factors in interactive models of contextual influences on children's school adjustment. Despite the developmental and practical implications and the plethora of research linking temperament and teacher–child relationships to children's school adjustment, relatively few studies have focused on these factors, particularly in children at risk. For this reason, the current study examines how children's temperament, specifically their self-regulatory abilities, can influence the associations between teacher–child relationships and low-income preschoolers’ socioemotional adjustment in the classroom.

TEACHER–CHILD RELATIONSHIPS: CONFLICT AND CLOSENESS

Just as biobehavioral factors can influence how children adjust within the school environment, school context factors, in particular teacher–child relationships, play a significant role in children's lives and therefore have important implications for children's overall development and school adjustment. Two distinct patterns of teacher–child relationships have been found to relate to children's socioemotional development (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994; Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995). These reflect the level of conflict among teacher–child interactions and the prevalence of closeness within the teacher–child relationship (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Hamre & Pianta, 2001). Conflictual teacher–child relationships are characterized by inharmonious interaction and a lack of understanding within the relationship, which may foster feelings of anxiety, anger, and alienation (Birch & Ladd, 1997). Closeness, on the other hand, includes the degree of warmth and open communication that exists between a teacher and student, which functions as support for children within the environment (Birch & Ladd, 1997). Although there are often varying levels of both closeness and conflict in any teacher–child relationship, research suggests that these constructs have significant differential effects on children's school adjustment (Hamre & Pianta, 2001).

The literature on the prevalence of child behavior problems following negative teacher–child interactions has identified teacher–child conflict as a relationship factor that can account for this association (Hamre, Pianta, Downer, & Mashburn, 2008). In relationships characterized as conflictual, teachers are more likely to seek punitive actions for child misbehaviors and are more likely to withdraw from interactions or ignore these students. A consequence of this behavior can be that children who need the most attention are neglected by their teachers (Sutherland & Morgan, 2003). Studies examining the teacher–child relationship and school adjustment have found that conflict (antagonistic, disharmonious interactions) in the relationship was significantly correlated with higher levels of children's school avoidance, aggression, disruptive behaviors, and social withdrawal (Birch & Ladd, 1997, 1998; Howes, 2000). Hamre and Pianta's (2001) study examining the relation between teacher–child relationships and children's trajectories through middle school found that conflictual relationships with teachers in kindergarten were related to low math and language arts grades, lower standardized test scores, less positive work habits, and increased disciplinary infractions throughout upper elementary and middle school, particularly among students with early risk of behavioral difficulties. Thus, these findings provide strong evidence that early conflictual teacher–child relationships are related to children's lack of adjustment to school even in later grades.

In contrast, teacher–child closeness has emerged as an important factor in predicting socioemotional success in young children. Closeness between teacher and student is positively linked to child academic performance, child school liking, and self-regulated behaviors (Birch & Ladd, 1997). Even more compelling, studies of teacher–child closeness and subsequent school adjustment have found that closeness in preschool and kindergarten is related to more positive work habits, less aggression, fewer disruptions, and less teacher–child conflict in subsequent grades (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Howes, 2000). The quality of the teacher–child relationship can also serve as a buffer between negative parenting and children's adjustment, especially among children with a difficult temperament. Research has shown that close teacher–child interactions can even buffer the negative consequences of experiences such as relationship stress, parental depression, and child maltreatment (Werner & Smith, 1982). Overall, when teachers report having close relationships with their students, these students exhibit higher social competence, fewer behavior problems, and more school liking than students with more conflictual relationships (Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Pianta & Nimetz, 1991); however, there is very little work on the relation of teacher–child relationships to children's socioemotional adjustment for children with different temperamental vulnerabilities.

CHILD TEMPERAMENT: EFFORTFUL CONTROL

Young children make impressions on their teachers as soon as they enter the classroom, and these impressions are often formed based on the characteristics and behaviors exhibited by children within the classroom context. Some characteristics, such as sex of the child, are both static and readily apparent to teachers, whereas others, such as children's temperament, are more psychological or behavioral in nature (Myers & Pianta, 2008). The current study focuses on effortful control, a prominent dimension of temperament that has been consistently linked to children's socioemotional adjustment. Temperament is defined as constitutionally based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation that are shaped over time by heredity, maturation, and experience (Rothbart & Ahadi, 1994). Effortful control, which refers to a child's ability to use attentional resources and to inhibit emotional and behavioral responses when presented to fear- or anger-inducing stimuli, is often used as an indicator of the self-regulatory aspect of temperament (Eisenberg et al., 2000). Children's regulatory abilities are particularly important during early childhood because children are learning to regulate their emotions and behaviors in socially appropriate, adaptive ways in contexts outside of the home (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Thompson, 1994). Children need to be able to regulate their emotions and behaviors not just to effectively learn needed academic skills but also to navigate social relationships within the classroom context (Howse, Calkins, Anastopoulos, Keane, & Shelton, 2003; Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, Swanson, & Reiser, 2008). Thus, it can be concluded that dysregulation will create a disruption and interference with children's overall learning, hence underscoring the importance of examining this construct in relation to children's adjustment to school.

The regulatory construct of effortful control has been shown to influence young children's socioemotional and overall school adjustment in particular, because children's ability to regulate their emotions and behavior can affect the prevalence and quality of interactions with individuals (i.e., teachers, peers) within the school environment (Eamon, 2001; Rothbart & Jones, 1998). For example, children with low effortful control may be viewed as purposefully disruptive, thereby increasing the likelihood of negative teacher–child interactions and problem behaviors in the classroom. However, children with high effortful control may be perceived by the teacher as being highly engaged in classroom activities, more intelligent, and generally better adjusted. Thus, children with high effortful control are more likely to evoke more positive teacher behaviors, such as more responses to questions/difficulties, presentation of more learning opportunities, and giving out of more privileges in the classroom (Myers & Pianta, 2008; Stipek, 1998).

Although teachers are more likely to engage in positive interactions with children who exhibit behaviors that they consider appropriate in the classroom context (Keogh, 2003), recent research suggests that positive teacher–child interactions may be particularly salient for children predisposed to problems with self-regulation (Blair, 2002; Rimm-Kaufman, 2002). Behaviorally at-risk students are more likely to exhibit fewer disruptive behaviors and learn more adaptive behaviors when paired with supportive teacher–child relationships (Hughes, Cavell, & Willson, 2001; Meehan, Hughes, & Cavell, 2003), suggesting that positive teacher–child relationships may be related to fewer socioemotional and behavioral difficulties among low-income children with self-regulatory difficulties. On the other hand, children demonstrating difficulties in effortful control have been shown to exhibit more externalizing behavior problems, particularly when these children experience negative caregiver–child interactions (Morris et al., 2002). Nevertheless, few studies have examined the associations between child temperament and classroom relationships, particularly with reference to children with socioeconomic risk.

The current investigation examined links among teacher–child relationships and children's effortful control in a sample of rural low-income preschoolers. Using these data, the current investigation tested the following hypotheses. We hypothesized that both effortful control and teacher–child relationships (closeness and conflict) would be uniquely associated with children's socioemotional adjustment (conduct problems, peer problems, prosocial behaviors, and emotional symptoms) in preschool. The primary hypotheses of the current study, however, focused on examining whether children's effortful control would moderate the link between teacher–child relationship quality and children's socioemotional adjustment. In general, as has been found in other studies (e.g., Morris et al., 2002), we expected that children low in effortful control would be more impacted by the teacher–child relationship. Specifically, it was hypothesized that the relationship between teacher–child conflict and children's socioemotional difficulties would be stronger among children low in effortful control. Additionally, given evidence that positive teacher behaviors and teacher sensitivity are related to more socioemotional competence in children who may be at risk for self-regulatory difficulties (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002), we hypothesized that the relationship between teacher–child closeness and children's socioemotional success would also be stronger among children low in effortful control compared to children high in effortful control.

METHOD

Design and Participants

One hundred and forty 4- and 5-year-old Head Start children (77 boys and 63 girls), their parents (mostly mothers), lead teachers, and teacher assistants (9 classrooms, 11–19 children per class) from a rural southern region of the United States participated in this study. The ethnic makeup of the sample was 46% Euro-American, 48% African American, and 2% Hispanic/Latin American, with 4% of families not reporting ethnicity. Fifteen percent of participating mothers did not complete high school, 35% were high school graduates, and 26% had some college or technical training. Lead teachers were female (100%), and most were African American (78%). On average, lead teachers (N = 9) had between 15 and 20 years of early childhood teaching experience, were CDA (Child Development Associate) certified, and had either an associate's degree in child development (n = 7) or a bachelor's degree in a field related to child development (n = 2). Teacher assistants were also all female (100%) and predominantly African American (67%). The majority of teacher assistants (N = 9) were either CDA certified or were enrolled in child development courses.

Procedure

Initial recruitment of children/parents began at Head Start parent meetings and school registration, where researchers explained the nature of the study and answered questions. Of the 180 families represented at the center, 140 families agreed to participate in the current study (participation rate = 78%). Information explaining the study and a number to call were also sent home to parents. All parents were assured that participation was voluntary (the consent form was verbally discussed). Parents completed two consent forms: consent for the parent and child to participate and consent to obtain information from the child's teacher. Teachers and teacher assistants were given a copy of the parent's consent to contact the teacher and were also given their own consent form to sign. Parents, lead teachers, and teacher assistants completed questionnaires in the fall/spring semesters of one school year and received monetary compensation. Parent packets were completed at parent meetings or sent home from school with the child throughout the fall semester. Lead preschool teachers completed questionnaires on the teacher–child relationship later in the fall, whereas preschool teacher assistants (who are often called upon to deal with behavioral aspects of classroom management) completed questionnaires on children's socioemotional adjustment later in the spring of the school year. All children remained with the same lead teacher and teacher assistant throughout the entire school year.

Measures

Measures assessed children's temperament, problem behaviors, quality of social relationships, and school adjustment. A basic demographic questionnaire was completed by parents to gather general information (parent education and income, marital status, people living in the home, child birth date, etc.).

Temperament

Parents completed shortened scales (attention focusing, attention shifting, and inhibitory control) of the Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ). Internal consistency estimates for the CBQ ranged from .67 to .94 in previous studies (Eisenberg et al., 1997; Goldsmith & Rothbart, 1991). Respondents rate how true an item is for the child on a 7-point scale (from 1 = extremely untrue to 7 = extremely true). The 23 questions that made up the attention (α = .66, 13 items) and inhibitory control (α = .71, 10 items) scales were combined as an indicator of effortful control, a common measure of regulation used in current research on children (see Eisenberg, Morris, & Spinrad, 2005; Morris et al., 2002). Items for the effortful control scale included “Has a hard time shifting from one activity to another” and “Is usually able to resist temptation when told s/he is not supposed to do something.” Internal consistency reliability of the combined items on the scale exceeded .80.

Teacher–child relationships

Lead teachers’ reports of teacher–child relationships were measured via the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS). The STRS is a teacher self-report measure assesses the teacher–student relationship for a particular child. This measure has 31 items and uses a 5-point Likert-type scale (Pianta & Steinberg, 1992). The STRS measures teacher–child dynamics and was used to assess teacher–child closeness (α = .73) and conflict (α = .69). Questions include items such as “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child” and “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other.” Scores on the STRS have been found to correlate with competence behaviors at home and school (Pianta & Steinberg, 1992).

Socioemotional adjustment

Teacher assistants completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, which is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire that asks about 25 child attributes, some positive and others negative. The 25 items are divided between five scales of five items each. In the current study focusing on children's socioemotional adjustment, only the scores emotional symptoms (α = .73), conduct problems (α = .87), peer problems (α = .60), and prosocial behaviors (α = .81) were used. Respondents rate how true an item is for the child on a 3-point scale (from 1 = not true to 3 = certainly true). Questions include items such as, “Often complains of headaches, stomachaches, or sickness,” “Often fights,” “Gets along better with adults than with other children,” and “Shares readily with other children,” respectively. The teacher form for ages 4 to 10 was used for this study. The SDQ has good discriminant and predictive validity and correlates highly with the Rutter Questionnaires as well as the Child Behavior Checklist (Goodman, 1997; Goodman & Scott, 1999).

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for all the major variables are presented in Table 1. Examination of the distribution of study variables indicated that the emotional symptoms and conduct problems variables were positively skewed, so these variables were transformed (log x) to approximate normality before model fitting. After transformation, skewness and kurtosis indices were between –1.0 and 1.0, implying that not much distortion was to be expected. At the child level, ANOVAs indicated that there were no significant differences for child gender, parent education level, or teacher ethnicity in relation to variables of interest; however, there were significant racial differences (African American vs. Caucasian) in effortful control, F(1, 136) = 4.62, p = .03. Specifically, African American parents rated their children higher in effortful control (M = 4.76, SD = 0.88) than did Caucasian parents (M = 4.22, SD = 0.79). Given previous research that has indicated that structural characteristics are related to children's school adjustment a nd should be taken into account in research examining these associations, ANOVAs were used in order to examine whether study variables differed by teacher (lead teacher only) level of education and experience. Findings indicated that there were significant differences in teacher ratings of both closeness and conflict by teacher years of experience and teacher education level. Specifically, teachers with more than 10 years of early childhood teaching experience reported significantly less teacher–child conflict (M = 1.62, SD = 0.62), F(1, 138) = 5.72, p = .02, and more closeness with students (M = 4.06, SD = 0.54), F(1, 137) = 13.79, p = .00, than did teachers with less than 10 years of experience (M = 1.95, SD = 0.76; M = 3.57, SD = 0.78, respectively). Additionally, teachers with a bachelor's degree reported significantly more teacher–child conflict (M = 1.75, SD = 0.62), F(1, 138) = 3.67, p = .05, than teachers with a CDA/associate's degree (M = 1.49, SD = 0.52). Thus, child ethnicity, lead teacher education level, and teacher years of experience were added as covariates into the predictive model.

TABLE 1.

Partial Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Major Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effortful control (P) | — | .17 | –.21* | –.11 | –.05 | –.29** | .21* | 4.47 | .88 | 2.22 | 6.61 |

| 2. Teacher–child closeness (LT) | — | –.38*** | –.29** | –.35*** | –.12 | .08 | 3.88 | .64 | 2.18 | 4.81 | |

| 3. Teacher–child conflict (LT) | – | .36*** | .29** | .48*** | –.15 | 1.72 | .68 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 4. Emotional symptoms (TA) | — | .29** | .07 | .14 | 1.27 | .51 | 1.00 | 2.80 | |||

| 5. Peer problems (TA) | — | .21* | –.33*** | 1.80 | .33 | 1.00 | 2.40 | ||||

| 6. Conduct problems (TA) | — | –.61*** | 1.39 | .50 | 1.00 | 3.00 | |||||

| 7. Prosocial behaviors (TA) | — | 2.38 | .45 | 1.20 | 3.00 |

Note. P = parent report; LT = lead teacher report; TA = teacher assistant report.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Because 140 children were nested within nine classrooms (ranging from 11 to 19 children per class), hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used in order to assess individual and classroom differences in child socioemotional outcomes (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2000). With an average of 15 children nested within classrooms, the assumption of independence of observations was violated for preschoolers sharing classroom membership. In addition, HLM does not require normally distributed outcome or predictor variables, but model residuals are assumed to be normally distributed. All analyses were also conducted with linear regression and were highly similar. Additionally, the intraclass coefficient, which measures the “proportion of total variance of a variable that is accounted for by clustering of cases” (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003, p. 537), revealed the presence of significant differences in outcomes attributable to classroom membership: emotional symptoms (16%), peer problems (12%), prosocial behaviors (23%), and conduct problems (16%), thus justifying the use of an HLM approach.

To address the first research question, we examined the extent to which children's effortful control and relationships with were uniquely associated with their socioemotional adjustment, controlling for child (Level 1) and teacher (Level 2) characteristics. The Level 1 model specified children's ethnicity (0 = Caucasian, 1 = other ethnic groups), children's effortful control, and each child's relationship with his or her lead teacher (closeness or conflict). The Level 2 model of classroom and teacher characteristics was entered as teacher level of education (0 = CDA/associate's, 1 = bachelor's) and years of teaching experience (0 = less than 10 years, 1 = 10 years or more). Finally, the interaction of effortful control with either teacher–child closeness or teacher–child conflict was entered separately to explore whether the associations between teacher–child relationships and student socioemotional outcomes were moderated by children's effortful control. In testing interactions, all predictor variables were centered (M = 0) prior to inclusion in the HLM models in order to minimize multicollinearity and improve the interpretability of the results (Aiken & West, 1991). The magnitude and direction of the coefficients indicated associations between socioemotional adjustment variables and children's effortful control and relationships with teachers.

Bivariate Associations Between Predictors and Preschool Outcomes

Bivariate correlations of teacher assistants’ reports of socioemotional adjustment, lead teachers’ reports of teacher–child relationships, and parents’ reports of effortful control are presented in Table 1. There were significant negative relations between parent ratings of effortful control and teacher ratings of teacher–child conflict and conduct problems. There was a positive relationship between children's effortful control and prosocial behaviors as rated by teacher assistants. In terms of teacher–child relationships, lead teachers’ reports of closeness were significantly related to teacher assistant reports of lower emotional symptoms and peer problems. In addition, lead teacher reports of conflict were significantly related to higher emotional symptoms, peer problems, and conduct problems; however, prosocial behaviors were not significantly related to teacher–child conflict or closeness.

Predicting Preschool Socioemotional Outcomes From Effortful Control and Teacher–Child Relationships

Tables 2 and 3 present regression coefficients and standard errors that indicate the magnitude of associations between predictors and socioemotional adjustment variables. Predictive models were run for each outcome variable, separately for closeness and conflict, for a total of eight models. After controlling for child (ethnicity) and teacher variables (education, experience), effortful control was negatively associated with conduct problems (t = –2.54, p ≤ .01) and positively associated with prosocial behaviors (t = 2.06, p ≤ .05) but was not associated with emotional symptoms or peer problems. In addition, teacher–child closeness was negatively associated with peer problems (t = –2.38, p ≤ .05) and conduct problems (t = –2.79, p ≤ .01) and positively associated with prosocial behaviors (t = 2.36, p ≤ .05). Teacher–child conflict, on the other hand, was positively associated with emotional symptoms (t = 2.37, p ≤ .05), peer problems (t = 2.04, p ≤ .05), and conduct problems (t = 5.22, p ≤ .001); teacher–child conflict was negatively associated with prosocial behaviors (t = –2.10, p ≤ .05).

TABLE 2.

Regression Coefficients in the Hierarchical Linear Models Predicting Socioemotional Outcomes From Covariates, Effortful Control, Teacher–Child Closeness and Their Interaction

| Outcome |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Emotional Symptoms (TA) B (SE) | Peer Problems (TA) B (SE) | Conduct Problems (TA) B (SE) | Prosocial Behaviors (TA) B (SE) |

| Level 1 predictors: Child | ||||

| Child ethnicitya | –.02 (.03) | –.00 (.06) | .09 (.08) | –.07 (.08) |

| Effortful control (P) | –.02 (.02) | .03 (.03) | –.16 (.02)** | .10 (.05)* |

| Teacher–child closeness (LT) | –.04 (.03) | –.19 (.06)** | –.22 (.09)* | .21 (.08)* |

| Level 2 predictors: Teacher | ||||

| Teacher years of experienceb | .13 (.09) | .06 (.11) | –.02 (.08) | –.24 (.14) |

| Teacher education levelc | .03 (.08) | –.19 (.10) | –.06 (.08) | .01 (.14) |

| Interactions | ||||

| Closeness × Effortful Control | –.03 (.03) | .05 (.05) | .03 (.07) | –.01 (.06) |

Note. TA = teacher assistant report; P = parent report; LT = lead teacher report.

Caucasian = 0, all other ethnic groups = 1.

0 = less than 10 years,1 = 10 years or more.

0 = Child Development Associate credential or associate's degree, 1 = bachelor's degree.

p ≤.05.

p ≤ .01.

TABLE 3.

Regression Coefficients in the Hierarchical Linear Models Predicting Socioemotional Outcomes From Covariates, Effortful Control, Teacher–Child Conflict, and Their Interaction

| Outcome |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Emotional Symptoms (TA) B (SE) | Peer Problems (TA) B (SE) | Conduct Problems (TA) B (SE) | Prosocial Behaviors (TA) B (SE) |

| Level 1 predictors: Child | ||||

| Child ethnicitya | –.03 (.03) | –.01 (.06) | .06 (.08) | –.05 (.08) |

| Effortful control (P) | –.01 (.02) | .01 (.03) | –.13 (.02)** | .11 (.05)* |

| Teacher–child conflict (LT) | .06 (.03)* | .11 (.05)* | .38 (.03)*** | –.16 (.07)* |

| Level 2 predictors: Teacher | ||||

| Teacher years of experienceb | .10 (.09) | .02 (.13) | –.21 (.21) | –.20 (.14) |

| Teacher education levelc | .05 (.08) | –.09 (.10) | –.17 (.21) | .01 (.14) |

| Interactions | ||||

| Conflict × Effortful Control | –.07 (.03)* | –.15 (.06)* | –.05 (.08) | .06 (.08) |

Note. TA = teacher assistant report; P = parent report; LT = lead teacher report.

Caucasian = 0, all other ethnic groups = 1.

0 = less than 10 years,1 = 10 years or more.

0 = Child Development Associate credential or associate's degree, 1 = bachelor's degree.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Predicting Preschool Socioemotional Outcomes From the Interaction of Effortful Control and Teacher–Child Relationships

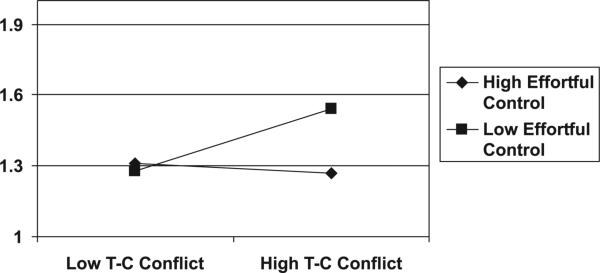

No significant interactions were found between effortful control and teacher–child closeness; however, the interaction of effortful control and teacher–child conflict was significantly associated with both emotional symptoms (t = –1.98, p ≤ .05) and peer problems (t = –2.31, p ≤ .05). Regression coefficients and standard errors for these interactions are presented in Table 3. For significant interactions, unstandardized slopes were examined among relationships high (1 SD above the mean) versus low (1 SD below the mean) on effortful control. Results indicated that higher teacher–child conflict was significantly associated with more emotional symptoms and peer problems among children with low effortful control; however, teacher–child conflict was not significantly associated with socioemotional outcomes in children with high effortful control. The results of these analyses are graphed in Figures 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Levels of emotional symptoms for low-income preschoolers with high and low effortful control for teacher–child (T-C) relationships with varying levels of conflict.

FIGURE 2.

Levels of peer problems for low-income preschoolers with high and low effortful control for teacher–child (T-C) relationships with varying levels of conflict.

DISCUSSION

This study is one of only a few that has investigated contextual and dispositional influences on socioemotional adjustment in rural, low-income children during the preschool period. Findings from this study provide evidence for the important role of effortful control in children's preschool behavioral adjustment and highlight the importance of examining teacher–child closeness and conflict in relation to children's socioemotional adjustment. Most important, this study provides evidence that among children with low effortful control, negative teacher–child relationships are related to more emotional symptoms and problems with peers. In contrast, teacher–child conflict was not related to difficulties among children with higher effortful control, suggesting that promoting self-regulation skills in preschool children identified as at risk may enhance positive socioemotional outcomes in low-income children.

The current study supports and expands upon the literature by demonstrating the role of effortful control in relation to socioemotional adjustment in preschool. Specifically, effortful control was significantly associated with conduct problems and prosocial behaviors in the preschool classroom. Findings also indicate that low-income children with low effortful control are at the greatest risk for having socioemotional difficulties at school, which replicates a pattern found in previous studies (see Eisenberg et al., 1995, 1999, 2004). The ability to regulate emotions and behaviors may nurture skills needed in order to conduct positive social interactions and engage in constructive behavior with peers (Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Cumberland, 2006). In previous studies, effortful control in young children was related to managing negative emotions, prosocial behaviors, and social competence (Eisenberg et al., 1993; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006). This study as well as previous research on effortful control lays the foundation for future research on school readiness and improving young children's school success by suggesting that self-regulation is a key component of children's early school adjustment.

Results of the current study indicate that teacher–child closeness is significantly associated with children's socioemotional adjustment in the classroom; however, teacher–child closeness was not differentially related to socioemotional outcomes for children depending on their level of effortful control, indicating that teacher–child closeness is an important predictor of socioemotional adjustment regardless of temperament. Positive teacher–child relationships are important because teachers may influence a child's emerging cognitive skills through the social and personal experiences that they provide for children and by encouraging and modeling behaviors for social interaction (Gauvain, 2001). For example, the structure and positive nature of interactions that teachers provide in face-to-face encounters and during the activities that they arrange for children seem to be most effective in helping children learn about and gradually adopt new social and cognitive skills (Rogoff, 1990). Rogoff (1995) stated that the actual adult–child interaction itself may provide children with routines that they can use for more complex activities, like providing representations of meaningful actions on which children can build to use in their own social and behavioral repertoires. These findings provide evidence that children may be using positive teacher–child interactions as representations for positive social relationships, thus translating to their positive behaviors in the classroom setting. Future research that uses observations of teachers and students and how their experiences generalize to other social interactions (i.e., peers, teachers in later grades) would allow for greater understanding of the mechanisms involved in these relationships.

In accordance with our expectations, findings from the current study indicate that teacher–child conflict is also significantly associated with a variety of socioemotional outcomes, particularly classroom conduct problems. In addition, teacher–child conflict is particularly related to socioemotional difficulties (emotional symptoms, peer problems) in the classroom for children identified by their parents as being low in effortful control. Early childhood classrooms are viewed as a social template in which children learn to regulate their emotions in socially appropriate ways and begin to establish relationship patterns with others (e.g., teachers, peers) that will continue over the transition to formal schooling (Howes et al., 1994). During teacher–child interactions, teachers can both consciously and unconsciously react negatively to children's negative attributes, thus increasing the likelihood of teacher–child conflict in the classroom. These negative teacher–child interactions not only serve as a template for negative adult–child interactions for young children but, when combined with both environmental and temperamental risk, make it significantly more likely that these children will exhibit more socioemotional difficulties in the classroom. Conversely, when teachers are sensitive to children's vulnerabilities and model appropriate social behaviors, children, especially those at risk for difficulties in self-regulation, are more likely to exhibit self-reliance, greater attentional control, and fewer problem behaviors in the preschool classroom (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002).

There are several strengths to the current study. First, this study used a rural, low-income sample of children to assess socioemotional adjustment in preschool; this tends to be an understudied population of students. Second, the current study used a multi-informant approach to data collection by using parent, lead teacher, and teacher assistant reports of contextual and dispositional influences on low-income children's school adjustment. It is also important to note that instead of lead teacher reports of outcomes, the current study used teacher assistant reports of children's socioemotional adjustment; preschool teacher assistants are most often responsible for behavioral management within the early childhood classroom. Teachers’ perceptions of children's behavior can vary, even within the same classroom context. Using teacher assistants’ reports of child outcomes offered the opportunity to reduce the likelihood of shared method variance (which is often a problem when assessing school factors) in using lead teachers’ reports of relationships and school outcomes.

The concurrent nature of the data did not allow for exploring the direction of effects or causality; however, future work using longitudinal designs would allow researchers to better understand the interrelatedness of the factors over time. In addition, although parent report of temperament has consistently been related to child school outcomes in studies assessing similar constructs (see Eisenberg et al., 1997; Goldsmith & Rothbart, 1991), the current study lacked unbiased perceptions of child temperament. Obtaining observer reports of children's temperament-related reactions in naturalistic settings over time (i.e., classroom) or in a more controlled environment would allow for more objective and unbiased estimates of children's effortful control. Despite this limitation, it is important to note that when examining constructs like effortful control, obtaining parent reports, who are privy to their children's characteristics and behaviors across settings, offers the opportunity to assess children's overall effortful control over time, thus will be more relevant and more associated with children's socioemotional adjustment across settings.

Pianta (1999) posited that pursuing research that examines correlates, determinants, and consequences of relationships between students and teachers (i.e., how children and teachers are affected by relationships of varying quality) would highlight risk and protective processes for both students and teachers, thus providing valuable tools for supporting the construction of positive school and classroom contexts. Findings of the current study confirm past research suggesting that both effortful control and teacher–child relationships are important predictors of preschoolers’ socioemotional adjustment. At the same time, they offer evidence that the combination of these factors, particularly teacher–child conflict and effortful control, can explain variations in children's socioemotional outcomes.

Because children's early experiences in school set the foundation for later school success, understanding the important role of children's temperament in combination with teacher–child relationships can aid in the creation of intervention and prevention programs aimed at promoting school readiness and reducing problem behaviors in at-risk samples. Through children's relationships with teachers, factors such as social behaviors, self-regulation, and achievement motivation can be improved for children already identified as having school difficulties; therefore, intervention should be considered within this relational context (Pianta, 1999). In terms of practical applications, when children are identified as at risk for socioemotional difficulties, teachers, administrators, and researchers should attempt to work together to discover effective ways of decreasing the prevalence of problem behaviors in the classroom. The findings from the current study suggest that fostering emotion regulation skills in at-risk children and improving teacher–child interactions are important areas for intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was primarily supported by Department of Health & Human Services Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Grant 90YD0182 to the first author and is part of a larger project funded by the National Institute of Child Development (NICHD) Grant 1R03HD045501-01A1 to the second author. We thank the many parents, students, educators, and administrators who participated in the project.

Contributor Information

Sonya S. Myers, Vanderbilt University

Amanda Sheffield Morris, Oklahoma State University.

REFERENCES

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher–child relationship and children's early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Children's interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:934–946. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of child functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57(2):111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK. The effects of poverty on children's socioemotional development: An ecological systems analysis. Social Work. 2001;46:256–266. doi: 10.1093/sw/46.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bernzweig J, Karbon M, Poulin R, Hanish L. The relations of emotionality and regulation to preschoolers’ social skills and sociometric status. Child Development. 1993;64:1418–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children's social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC, Shepard S, Guthrie IK, Mazsk P, et al. Prediction of elementary school children's socially appropriate and problem behavior from anger reactions at age 4–6 years. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1999;20:119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad TL. Prosocial behavior. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy B, et al. Prediction of elementary school children's externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71:1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS. Children's emotion-related regulation. In: Reese H, Kail R, editors. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 30. Elsevier; New York: 2002. pp. 189–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS, Spinrad T. Emotion-related regulation: The construct and its measurement. In: Teti D, editor. Handbook of research methods in developmental psychology. Blackwell; New York: 2005. pp. 423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Rieser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, et al. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children's resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felner RD, Brand S, Dubois DL, Adan AM, Mulhall PF, Evans EG. Socioeconomic disadvantage, proximal environmental experiences, and socioemotional and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of a mediated effects model. Child Development. 1995;66:774–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvain M. The social context of cognitive development. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Rothbart MK. Contemporary instruments for assessing early temperament by questionnaire and in the laboratory. In: Angleitner A, Steau J, editors. Explorations in temperament. Plenum; New York: 1991. pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Scott S. Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: Is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:17–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658222914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children's school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC, Downer JT, Mashburn AJ. Teachers’ perceptions of conflict with young students: Looking beyond problem behaviors. Social Development. 2008;17(1):115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Social–emotional classroom climate in child care, child–teacher relationships and children's second grade peer relations. Social Development. 2000;9(2):191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Matheson CC, Hamilton CE. Maternal, teacher, and child care history correlates of children's relationships with peers. Child Development. 1994;65:264–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howse RB, Calkins SD, Anastopoulos AD, Keane SP, Shelton T. Early Education and Development. 2003;14:101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Willson V. Further support for the developmental significance of the quality of the teacher–student relationship. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh BK. Temperament in the classroom: Understanding individual differences. Brookes; Baltimore: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Do relational risks and protective factors moderate the linkages between childhood aggression and early psychological and school adjustment? Child Development. 2001;72:1579–1601. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClowry S. The science and art of using temperament as the basis for intervention. School Psychology Review. 1998;27:551–563. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan BT, Hughes JN, Cavell TA. Teacher–student relationships as compensatory resources for aggressive children. Child Development. 2003;74:1145–1157. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Essex MJ. Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- Myers SS, Pianta RC. Developmental commentary: Individual and contextual influences on student–teacher relationships and children's early problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(3):600–608. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Nimetz S. Relationships between teachers and children: Associations with behavior at home and in the classroom. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1991;12:379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Steinberg M. Teacher–child relationships and the process of adjusting to school. In: Pianta RC, editor. Beyond the parent: The role of other adults in children's lives. Vol. 57. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1992. pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Steinberg MS, Rollins KB. The first two years of school: Teacher–child relationships and deflections in children's classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush RW, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM5: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Scientific Software International; Chicago: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Early D, Cox M, Saluja G, Pianta R, Bradley R, Payne C. Early behavioral attributes and teachers’ sensitivity as predictors of competent behavior in the kindergarten classroom. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23:451–470. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford University Press; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In: Wertsch JV, del Río P, editors. Sociocultural studies of mind. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA. Temperament and the development of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:55–66. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Jones LB. Temperament, self-regulation, and education. School Psychology Review. 1998;27:479–491. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75:417–453. [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Cumberland A. Relation of emotion-related regulation to children's social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion. 2006;6:498–510. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipek D. Communicating expectations. In: Stipek D, editor. Motivation to learn: From theory to practice. Allyn & Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 1998. pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland KS, Morgan PL. Implications of transactional processes in classrooms for students with emotional behavior disorders. Preventing School Failure. 2003;48:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of a definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2–3):25–52. Serial No. 240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery-Chalfant KS, Swanson J, Reiser M. Prediction of children's academic competence from their effortful control, relationships, and classroom participation. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:67–77. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:715–730. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Smith E. Vulnerable but invincible. Wiley; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]