Summary

To assess the associations between a doctor diagnosis of asthma and wheezing (independent of a diagnosis of asthma) with sickle cell disease (SCD) morbidity, we conducted a retrospective review of Emergency Department (ED) visits to the Mount Sinai Medical Center for SCD between 1 January 2007 and 1 January 2011. Outcomes were ED visits for pain and acute chest syndrome. The cohort included 262 individuals, median age 23·8 years, (range: 6 months to 67·5 years). At least one episode of wheezing recorded on a physical examination was present in 18·7% (49 of 262). Asthma and wheezing did not overlap completely, 53·1% of patients with wheezing did not carry a diagnosis of asthma. Wheezing was associated with a 118% increase in ED visits for pain (95% confidence interval [CI]: 56–205%) and a 158% increase in ED visits for acute chest syndrome (95% CI: 11–498%). A diagnosis of asthma was associated with a 44% increase in ED utilization for pain (95% CI: 2–104%) and no increase in ED utilization for acute chest syndrome (rate ratio 1·00, 95%CI 0·41–2·47). In conclusion, asthma and wheezing are independent risk factors for increased painful episodes in individuals with SCD. Only wheezing was associated with more acute chest syndrome.

Keywords: sickle cell, asthma, wheeze, pain, acute chest syndrome

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is an inherited disorder of haemoglobin marked by recurrent vaso-occlusion, which manifests most commonly as paroxysmal attacks of debilitating pain. Since the 1983 case report of a girl with SCD whose pain episodes seemed to be precipitated by her asthma attacks (Perin et al, 1983), asthma has surfaced as a complex risk factor for increased SCD morbidity and mortality (Vichinsky et al, 1997; Pritchard et al, 2004; Nordness et al, 2005; Boyd et al, 2006, 2007; Sylvester et al, 2007a; Bernaudin et al, 2008;, Newaskar et al, 2011; Pritchard et al, 2012; Knight-Madden et al, 2005). Emerging data suggest that asthma is not the only cause of chronic wheezing in individuals with SCD, and that an asthma-like syndrome may be a pulmonary manifestation of SCD (transgenic SCD mice exhibit pulmonary inflammation in the absence of asthma, a potential aetiology for this asthma-like syndrome. Experimental induction of asthma in these mice further increases inflammation and airway reactivity) (Nandedkar et al, 2008; Newaskar et al, 2011; Pritchard et al, 2012). Asthma prevalence is the same as the general population (15–22%) in prospectively screened SCD cohorts. However, up to 60% of SCD patients report a history of wheezing, and up to 78% have obstructive pulmonary function patterns (Leong et al, 1997; Koumbourlis et al, 2001; Ozbek et al, 2007; Sylvester et al, 2007b; Strunk et al, 2008; Sen et al, 2009; Cohen et al, 2011; Field et al, 2011). Some of these patients with symptoms of wheezing probably have undiagnosed asthma; in others the symptoms may be due to SCD.

The relative importance of asthma and wheezing as risk factors for vaso-occlusive complications in SCD is undefined. Several paediatric studies identified associations between asthma and vaso-occlusive complications (pain episodes, acute chest syndrome and death) (Morris, 2009; Anim et al, 2011), but these did not investigate the presence of wheezing as a separate risk factor (Boyd et al, 2006, 2007; Glassberg et al, 2006). One prospective study of adults with SCD found that severe wheezing, but not asthma, was associated with increased SCD morbidity (Cohen et al, 2011).

This investigation compared wheezing versus a doctor diagnosis of asthma as risk factors for SCD morbidity in a cohort that includes both children and adults. Our hypothesis is that both asthma and wheezing will be associated with increased frequency of pain and acute chest syndrome. Adult data on this topic are lacking, the use of a cohort with children and adults allows us to test for age interactions with respect to our hypotheses.

Methods

Setting

The Mount Sinai Medical Center (MSMC) is an academic, tertiary care, level two trauma center with approximately 106 000 visits annually to the ED. The MSMC SCD clinics have a combined census (adult & paediatric) of 294 patients. The protocol for this study was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Study design and methods

This study was a retrospective chart review of all visits to the MSMC ED related to SCD between 1 January 2007 and 1 January 2011. ED patients with SCD were identified by a systematic search strategy. All ED charts that contained the word ‘sickle’ in the chief complaint or diagnosis were selected for review. From these charts a list of unique patients was created. The entire medical records of these patients (both ED and outpatient records) were reviewed. Before the start of the study, definitions were created for all study variables and kept in a manual of operations for the study protocol. Chart abstraction was performed by trained chart abstractors. Training included a review of study variable definitions, chart abstraction procedures and supervised abstraction of 25 charts. Data were abstracted directly from the electronic medical record into an SPSS database. Daily meetings were held with chart abstractors to ensure proper abstraction procedures. A 5% sample of charts were reviewed by a second abstractor and checked for inter-rater reliability. All laboratory values and clinical parameters were checked for outliers and missing data. Specifically, based on the distribution, each value below the 5th percentile and above the 95th percentile was re-confirmed for accuracy, and when discrepant, was changed accordingly. For all missing key variables, a second review of the chart was performed to determine if the data were not available or simply not recorded.

Definition of variables

Painful episode

The primary outcome for this study was the number of ED visits for painful episodes. An ED visit was defined as any visit to the ED (including patients who were admitted to the hospital, and those who were discharged home). A painful episode was defined as an ED visit that required treatment with opiates that could not be attributable to a cause other than SCD. In the event that the abstractor was not sure if a visit met criteria for a painful episode, the chart was reviewed by a second abstractor.

Acute chest syndrome

A secondary outcome for this study was the number of ED visits for acute chest syndrome, defined as a pulmonary infiltrate (excluding atelectasis and chronic findings) that required admission to the hospital (Vichinsky et al, 1997). Pneumonia was indistinguishable from acute chest syndrome, and thus considered an episode of acute chest syndrome in this analysis. Visits that met criteria for both painful episode and acute chest syndrome were recorded as both.

Asthma

Asthma was defined as a diagnosis of asthma documented in the medical history or problem list with supporting evidence from the medical record of prior healthcare encounters for asthma (henceforth referred to as ‘asthma’). The use of asthma medication was also recorded. When a diagnosis of asthma was made and no asthma medication was recorded during the ED visit, we confirmed the diagnosis of asthma with a review of the medical records for any hospital admissions, ED visits, clinic visits or medications for asthma. Similarly, if the patient was recorded in the medical records as having prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators, or a cysteinyl leucotriene receptor antagonist, but the ED visit record did not indicate a history of asthma, the abstractor was required to recheck all of the patient’s medical records for a diagnosis of asthma. An assumption was made that asthma is a chronic condition and life-long illness (patients who met study criteria for asthma were classified as asthma-positive at all visits) (Pritchard et al, 2012). In the event that the abstractor was not sure if criteria were met for a diagnosis of asthma, the chart was reviewed by a second abstractor.

Wheeze

A positive history of wheezing was defined evidence in the medical record that the patient ever had an episode of wheezing during the sampling frame. This included documentation of wheezing in the physical examination of any of the patient’s ED charts. Wheezing during an episode of acute chest syndrome was excluded.

Steady state values

Steady state values for haemoglobin, fetal haemoglobin, and leucocyte counts were recorded. Steady state haemoglobin and leucocyte counts were defined as the average of the three most recent measurements taken during routine follow up visits when the patient had no acute complaints. Steady state fetal haemoglobin percentage was defined as the most recent haemoglobin electrophoresis result available in the patient’s medical record. Haemoglobin electrophoresis results were discarded if there was evidence of recent transfusion. Evidence of transfusion on the electrophoresis was determined by a physician with specialty training in transfusion medicine who was blind to the study hypothesis.

Time

Time-weighted and time-independent analyses were performed. In the time-independent analyses, each subject contributed four person-years to the study (i.e. the patient contributed data for the entire 4-year sampling frame). In the time-weighted analysis, each patient’s contribution started after their first ED visit (e.g. a patient whose first ED visit was 10 days before the end of the sampling frame contributed 10 days of data).

Data analysis

Data were imported from the SPSS database into a comma separated values (csv) file. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Missing values were filled using a multiple imputation approach. T-tests, chi-square and non-parametric tests were used to compare mean differences and proportions when appropriate. Multivariable negative binomial regression models were used to estimate adjusted rate ratios for ED visits. Separate models were run using ED visits for pain and ED visits for acute chest syndrome as the outcome variable. Variables with biologically plausible, known associations with SCD morbidity were included in the multiple regression model. In addition to asthma and wheezing, covariates considered for inclusion were age, gender, sickle cell genotype, steady state haemoglobin, steady state leucocyte count, fetal haemoglobinpercentage, insurance status and history of tobacco smoking (Pritchard et al, 2004). Continuous variables were modelled with linear or quadratic terms when appropriate. Only covariate terms with P values below 0·2 remained in the final regression models. Models were run in a time-weighted and time-independent fashion. As the results did not change substantially with time-weighting, time-independent results are reported. To assess if the effect of asthma on SCD morbidity changes with age, a test for heterogeneity of effect was performed. For all tests, a two-sided alpha level of 0·05 was chosen as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

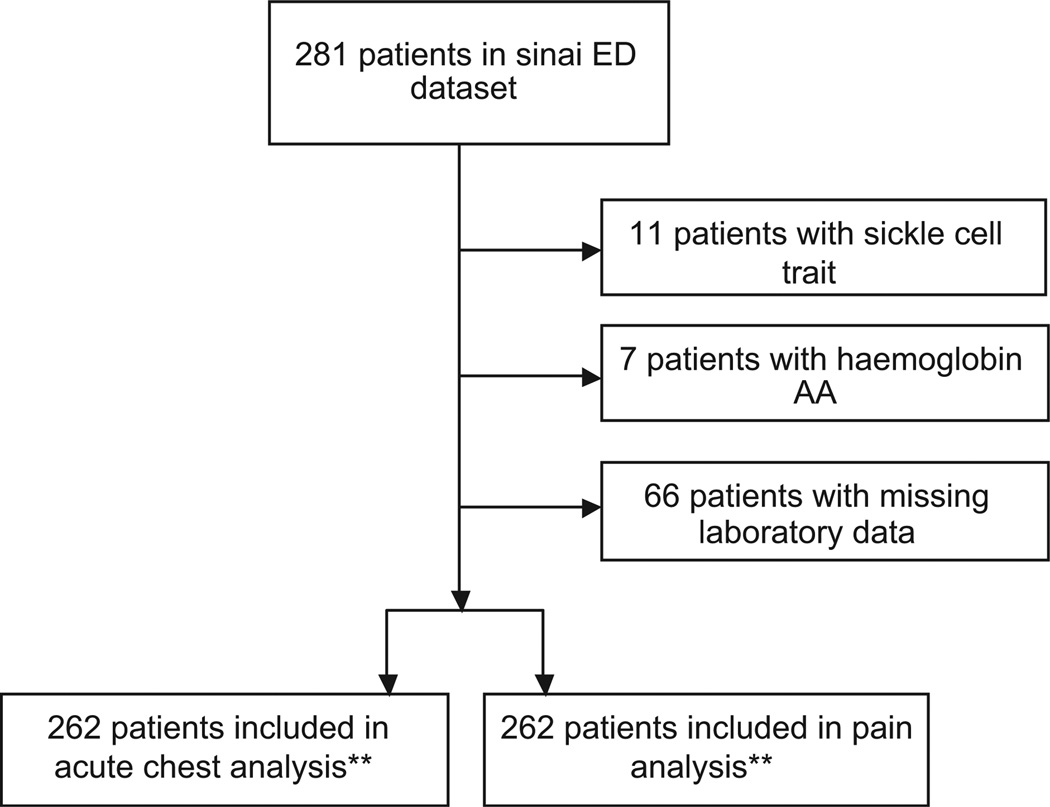

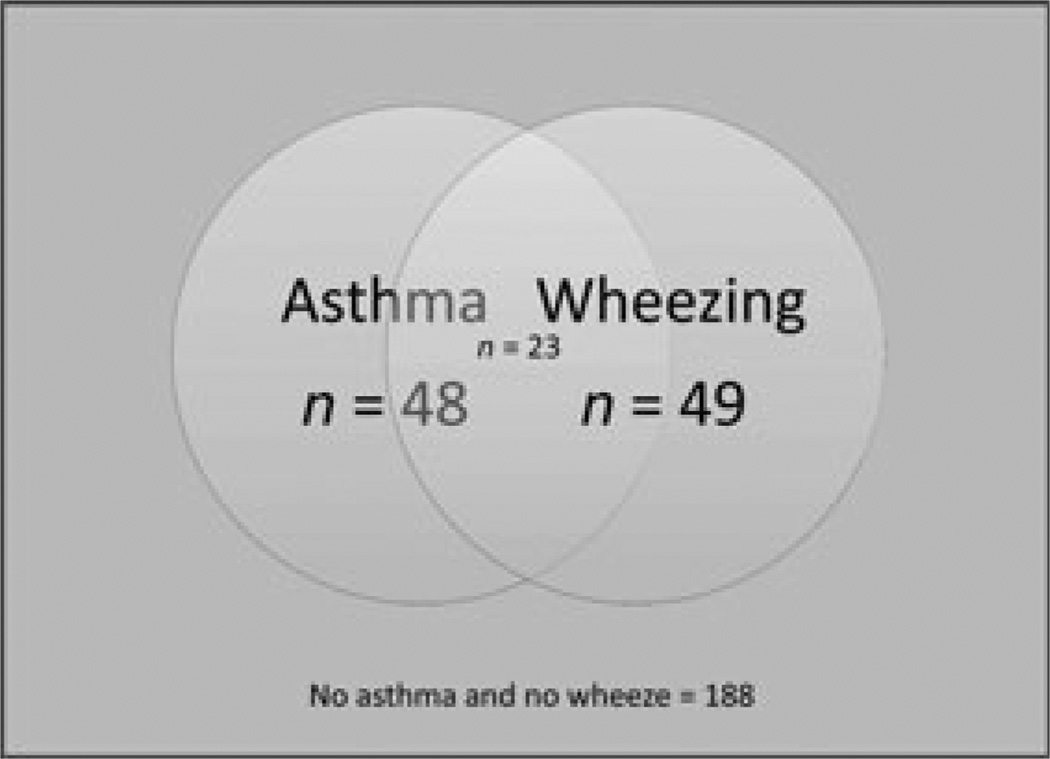

During the sampling time-frame, there were 2050 visits to the ED related to SCD. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the subjects are listed in Table I. Of the 281 unique patients in the dataset, 18 were excluded because review of the medical record revealed that they did not have SCD (11 patients with sickle cell trait, seven patients with AA haemoglobin) and one was excluded because they had only one visit to the hospital and left prior to being seen by a physician (i.e. there were no clinical data available for this patient). Thus, the sample included 262 patients for a total of 1048 patient-years of data (Fig 1). There were 1456 visits for pain (1·39 per patient-year) and 53 visits for acute chest syndrome (0·05 per patient year). The median age of the sample was 23·8 years (range 6 months to 67·5 years), and the cohort was 51% male. One quarter (25%) of the cohort had not been followed up with primary care or haematology during the sampling period, and 25% were prescribed hydroxycarbamide. There were 48 patients (18·3%) with a doctor diagnosis of asthma in the cohort and there were 49 (18·7%) patients who had at least one documented episode of wheezing. Wheezing and asthma did not overlap completely. Of the patients with a history of wheezing, 53·1% did not have asthma (Table II, Fig 2). Of the non-asthmatic patients with a positive history of wheezing, none had a history of atopic diagnoses (eczema or seasonal allergies) in their problem lists. Children with wheezing were not more likely than adults to carry a diagnosis of asthma (P = 0·09). Wheezing was less likely to occur during painful episodes (wheezing was found in 3·9% of visits for pain vs. 6·7% of visits without pain, P = 0·008), and individuals with asthma were no more likely than those without asthma to have wheezing occur outside of painful episodes (P = 0·24).

Table I.

Clinical characteristics and demographic data.

| Asthma | No Asthma | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 48 | 214 |

| ED Visits for Pain | 479 | 977 |

| Pain Visits/Patient-Year | 2·5 | 1·1 |

| ED Visits for Acute Chest Syndrome | 16 | 37 |

| Acute Chest Syndrome Visits/Patient-Year | 0·05 | 0·08 |

| Age in years | 22·4 (13·3–32·1) | 24·0 (16·8–33·3) |

| Gender (%male) | 50 | 51·4 |

| Tobacco Smoker (%) | 12·5 | 21·7 |

| History of Wheezing* (%) | 47·9 | 12·1 |

| IV Morphine Equivalents Given Per ED Visit | 13·6 mg (3·4–37·5) | 10·0 mg (2·0–28·3) |

| On Hydroxycarbamide (%) | 33·3 | 23 |

| Type of Insurance** (%) | ||

| Medicaid* | 83·3 | 67·6 |

| Medicare | 4·2 | 10·5 |

| Private Insurance* | 8·3 | 21·0 |

| Uninsured | 33·3 | 3·3 |

| Haemoglobin Genotype (%) | ||

| SS | 68·4 | 59·1 |

| SβThal0 | 10·5 | 9·1 |

| SβThal+ | 7·9 | 5·5 |

| SC | 13·2 | 25·0 |

| Other | 0 | 1·2 |

| Acute Laboratory Values† | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 92 (83–104) | 92 (82–110) |

| WBC count (×109/l) | 12·9 (10·8–17·1) | 13·7 (10·1–16·1) |

| Platelet count (×109/l) | 340 (273·2–442·0) | 341·6 (269·5–426·0) |

| Reticulocyte count (×109/l) | 7·3 (3·4–9·7) | 6·8 (3·6–9·7) |

| MCHC (g/l) | 343 (334–347) | 343 (334–349) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (iu/l) | 477·6 (384·0–632·0) | 473·5 (325·0–592·0) |

| Creatinine (µmol/l) | 61·9 (53·4–97·2) | 70·7 (61·9–88·4) |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/l) | 53·0 (27·4–94·1) | 37·6 (22·2–65·0) |

| Direct bilirubin (µmol/l) | 5·1 (3·4–10·3) | 6·8 (3·4–10·3) |

| Steady State Laboratory Values† | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 97 (85–105) | 92 (83–108) |

| Fetal Haemoglobin% | 5·8 (1·6–11·7) | 4·6 (1·7–10·3) |

| WBC count (×109/l) | 10·7 (8·7–13·6) | 10·1 (7·7–12·8) |

Difference between groups statistically significant (P < 0·05).

Values do not add up to 100% because patients can have different insurance at different visits.

Values are expressed as a median with Inter-quartile range in parentheses.

ED, Emergency Department; IV, intravenous; WBC, white blood cell; MCHC, mean cell haemoglobin concentration.

Fig 1.

Patient Selection. *1 patient was excluded from the dataset because they left prior to seeing a physician during their ED visit. This patient had no other visits to the hospital, thus no clinical information could be abstracted from their chart. **Multiple imputation was used to fill missing laboratory values for 66 patients.

Table II.

Overlap of wheezing with asthma diagnoses.

| Asthma |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | |

| History of Wheezing | |||

| No | 188 | 25 | 213 |

| Yes | 26 | 23 | 49 |

| Total | 214 | 48 | 262 |

Wheezing and asthma do not overlap completely. In this cohort, asthma was defined as a history of asthma documented anywhere in the patient’s medical record. ‘History of wheezing’ was defined as at least one visit to the hospital in which the presence of wheezing was documented in the patient’s physical examination or history of present illness. More than half of patients with a history of wheezing did not carry a diagnosis of asthma.

Fig 2.

Distribution and overlap of asthma and wheezing in the cohort.

Main results

Wheezing and asthma are independently associated with increased ED utilization for pain

In patients with asthma, there were 2·5 ED visits for pain per patient-year vs. 1·1 visits per patient-year in patients without asthma. In patients with at least one documented episode of wheezing, there were 2·8 ED visits for pain per patient-year vs. 1·1 visits per patient-year in patients without wheezing. After adjusting for baseline haemoglobin, phenotype and fetal haemoglobin percentage, a history of wheezing episodes was associated with a 118% increase in the frequency of ED visits for pain (relative risk [RR] = 2·18, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1·56–3·05) and asthma was associated with a 44% increase in ED utilization for pain (RR 1·44, 95% CI 1·02–2·04). There was no significant interaction between asthma and wheezing in the model (P = 0·66). Fetal haemoglobin percentage was inversely associated with ED utilization for pain: every 1% increase in fetal haemoglobin was associated with 2% fewer ED visits for pain (RR 0·98, 95% CI 0·96–0·99). Insurance status was also significantly associated with ED utilization for pain. Being uninsured was associated with a 76% increase in ED utilization for pain (RR 1·76, 95% CI 1·28–2·44). The association between asthma and painful episodes did not vary significantly with age (P = 0·27). Table III shows the results of the multiple regression models for the primary outcome of ED utilization for pain.

Table III.

Negative binomial regression model of ED visits for pain.

| Variable | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Visits for Pain | |||

| Asthma | 1·44 | 1·02–2·04 | 0·04 |

| Wheeze | 2·18 | 1·56–3·05 | <0001 |

| Age | 0·99 | 0·98–1·00 | 0·16 |

| Genotype | 0·88 | 0·79–0·98 | 0·02 |

| Fetal Hb Percentage | 0·98 | 0·96–0·99 | 0·01 |

| Insurance Status | 112 | 1·02–1·23 | 0·02 |

Final multiple regression model for the primary outcome: frequency of Emergency Department (ED) visits for painful episodes. Variables that fell out of the final model were steady state haemoglobin, steady state leucocyte count, gender and tobacco smoking.

Wheezing is associated with increased ED utilization for acute chest syndrome, while asthma is not

In patients with asthma, there were 0·08 episodes of acute chest syndrome per patient year vs. 0·04 episodes per patient year in patients without asthma. In patients with at least one documented episode of wheezing, there were 0·11 episodes of acute chest syndrome per patient year vs. 0·04 episodes per patient-year in patients without wheezing. There was no association between a diagnosis of asthma and the frequency of ED visits for acute chest syndrome (RR 1·00, 95% CI 0·41–2·47). However, a history of wheezing was associated with a 158% increase in the frequency of acute chest syndrome episodes (RR 2·58, 95% CI 1·11–5·98). Female gender was associated with a 65% reduction in ED visits for acute chest syndrome (RR = 0·35, 95% CI 0·17–0·74). Table IV shows the results of the multiple regression model for the secondary outcome of acute chest syndrome.

Table IV.

Negative binomial regression models of ED visits for acute chest syndrome.

| Variable | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Visits for Acute Chest Syndrome | |||

| Asthma | 1·00 | 0·41–2·47 | 0·99 |

| Wheeze | 2·58 | 1·11–598 | 0·03 |

| Age | 1·01 | 0·98–1·03 | 0·65 |

| Genotype | 0·73 | 0·52–1·01 | 0·06 |

| Gender | 0·35 | 0·17–0·74 | 0·01 |

| Fetal Hb Percentage | 0·97 | 0·92–1·02 | 0·22 |

| Insurance Status | 0·84 | 0·64–1·09 | 0·19 |

Final multiple regression model for the secondary outcome: frequency of ED visits for acute chest syndrome. Variables that fell out of the model were steady state haemoglobin, steady state leucocyte count and tobacco smoking.

Quality of documentation and EM practice patterns of treatment for wheezing in the ED

The electronic medical record was sufficient for abstractors to determine asthma status in 100% of subjects. There were 97 ED visits where the presence of acute wheezing was documented in the chart. Albuterol was administered to 48% of patients who suffered acute wheezing and oral steroids were administered to 20%. Patients with a diagnosis of asthma were more likely to receive albuterol (57% vs. 35%, P = 0·03) and steroids (28% vs 5%, P = 0·01) for wheezing. Patients who received albuterol for wheezing were younger than those who did not (26·5 years vs. 17·1 years, P = 0·01, mean difference 9·45 years, 95% CI 2·8–16·1). Of the patients with asthma, 71% (34) were not on prescription controller therapy (inhaled steroids, leucotriene modifying drugs).

Discussion

This study represents an analysis of the impact of asthma versus wheezing (independent of a diagnosis of asthma) on SCD morbidity in a cohort that includes both children and adults. The results of this study suggest that both asthma and wheezing are independent risk factors for increased SCD morbidity. Wheezing is associated with greater increases in painful episodes and acute chest syndrome than asthma.

Several studies have documented the association between asthma and SCD morbidity and mortality. The more recent observation that many SCD patients wheeze in the absence of asthma (Cohen et al, 2011; Field et al, 2011) raised questions as to how much wheezing and asthma contribute to SCD morbidity and how much they overlap. Cohen et al (2011) were the first to demonstrate, in a cohort of closely followed clinic patients, that self-reported episodes of severe wheezing are associated with SCD morbidity and mortality. Our study adds to the findings of Cohen et al (2011) in several ways. First, our study included a larger unselected cohort of patients, many of whom did not have a regular source of care. These data provide a more real-world assessment of this problem and confirms that the association between wheezing and SCD morbidity exists outside the relatively selected group of patients followed in specialized tertiary care centers. Second, the study reported by Cohen et al (2011) did not exclude acute chest syndrome as a potential cause of wheezing. Our analyses were more specific as we excluded acute chest syndrome to eliminate this potential misclassification bias. Cohen et al (2011) also did not specify when episodes of wheezing occurred in relation to vaso-occlusion. In our cohort, wheezing was observed by clinicians during the same sampling time-frame as painful episodes, which further supports a connexion between active pulmonary symptoms and frequent vaso-occlusion. Our study demonstrates that wheezing and asthma overlap only partially and are independent risk factors for SCD morbidity. In our cohort, more than half of patients with wheezing did not have physician diagnosis of asthma. This is consistent with prior reports that not all wheezing in SCD patients is due to asthma, and that an asthma-like syndrome may be a pulmonary manifestation of SCD (high rates of airflow obstruction (Koumbourlis et al, 1997, 2009, 2007, 2001; Ozbek et al, 2007) airway hyperreactivity (Field et al, 2011) and wheezing (Cohen et al, 2011) in SCD patients with and without asthma) (Anim et al, 2011; Newaskar et al, 2011). Our study is one of the first to suggest that this asthma-like syndrome may also be a risk factor for increased morbidity. Another potential question was whether episodes of wheezing were simply a manifestation of vasoocclusive pain (due to splinting, heavy breathing, or the release of inflammatory cytokines during vaso-occlusion). We found that episodes of wheezing were more likely to occur outside of painful episodes (P = 0·008). This further supports the concept that wheezing in SCD is a process independent of vasoocclusion. Wheezing was associated with a substantial increase in the frequency of acute chest syndrome in this study, whereas asthma was not. Acute chest syndrome is a major cause of mortality in SCD; however, the relative effect of wheezing and asthma on mortality could not be assessed by this study.

Data on the association between asthma and SCD morbidity come mostly from the paediatric literature, thus we chose to test for age effects in several ways. There was no age association between wheezing and asthma diagnosis. Children with wheezing were no more likely to carry an asthma diagnosis than adults. A recent study (Cohen et al, 2011) found no association between asthma and SCD morbidity, which raised the question of whether the effects of asthma on SCD morbidity are not present in adults. In our larger sample, we found that asthma was associated with increased SCD morbidity and that these effects do not change significantly from children to adults. Ultimately, age did not have significant interaction with any of the variables tested, however small sample size may have limited our power to detect age interactions. The lack of age interactions suggests that wheezing and asthma in SCD are cause for concern in any age group.

The association between wheezing and SCD morbidity has two important implications. First, a positive history of wheezing, regardless of patients’ asthma status, may be a method of identifying patients at increased risk for excess SCD morbidity. Second, wheezing was associated with greater increases in the rates of pain and acute chest syndrome when compared to asthma. This may be because wheezing captures both individuals with poorly controlled asthma and individuals with the asthma-like syndrome of SCD. We hypothesize that control of wheezing with inhaled corticosteroid or cysteinyl leucotriene receptor antagonist taken routinely, together with a beta-2 agonist for acute symptoms, could prevent vaso-occlusive complications of SCD. Prospective randomized controlled trials are necessary to evaluate these hypotheses.

The major limitation of this study is that the data are retrospective and from a single institution. Because the data are retrospective, our analyses probably underestimate the effects of wheezing on SCD morbidity. Wheezing is likely to have gone unrecognized in our cohort, which would result in misclassification that would bias our results towards the null hypothesis. Some portion of the association between wheezing and SCD morbidity in this cohort may be the result of unknown sources of bias due to local or institution-related factorsand can only be assessed by reproducing this study in other locations. Also, we may not have captured all ED visits in our cohort, as patients may have visited other EDs within New York City. This would only create bias away from the null hypothesis if patients without asthma and wheezing were more likely to visit other hospitals, and we have no reason to expect this to be the case. By selecting only patients who presented to the ED, a small number of mild cases of SCD were excluded. There were 262 patients in our cohort, and the entire SCD census at our institution includes 294 patients. Excluding these milder cases of SCD could bias the entire sample towards more severe cases of SCD, however it is unlikely this would create differential bias with respect to the primary hypothesis. Another potential criticism is that all documented episodes of wheezing could simply be the result of undiagnosed asthma. This is unlikely because we have documented previously that the operational definition of asthma used in this study is accurate,(An et al, 2011) and because the percentage of patients in this cohort who carry a diagnosis of asthma is within the range of previously reported estimates (Boyd et al, 2004; Field & DeBaun, 2009; Newaskar et al, 2011). If all individuals with wheezing in this cohort are assumed to have asthma, the prevalence of asthma would be 28·2%. This is higher than previous prospective estimates of the prevalence of asthma in SCD and the general population (Cohen et al, 2011; Field et al, 2011; Newaskar et al, 2011; http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/brfss/2010/lifetime/tableL5.htm. Furthermore, evidence already exists that not all wheezing in SCD is asthma, as a large percentage of children and adults with SCD are known to wheeze in the absence of other characteristics of asthma, such as atopy and airway hyperresponsiveness (Cohen et al, 2011; Field et al, 2011). In our cohort, of the non-asthmatic patients with a positive history of wheezing, none had a history of atopic disease (eczema or seasonal allergies) in their medical problem list.

As a clinical study, we can test for associations, but cannot elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of the SCD wheezing phenomenon. The associations identified by this study are, however, clinically important. Our data suggest that the mere presence of wheezing, regardless of underlying pathogenesis, may help to identify patients at increased risk for vaso-occlusion. Rather than detailed pulmonary/laboratory evaluations to determine which SCD patients have asthma, the more relevant question may be ‘do you wheeze?’ Diagnosis of asthma is particularly challenging in SCD because symptoms of both diseases overlap. Our data suggest that the criteria used to diagnose asthma in the general population may not accurately identify, in the SCD population, those who could benefit from therapy. In the general population, those who wheeze only occasionally with respiratory infections do not suffer from increased morbidity and do not benefit from long-term asthma controller medication (thus we maintain a higher threshold for initiation of treatment). This may not be true for individuals with SCD and must be prospectively explored. Asthma, a disease thought to result from a heterogeneous group of disorders, is diagnosed and treated clinically (usually without exploration of underlying mechanisms). We submit that the same may be possible for wheezing in SCD, however the threshold for treatment in the general population may not be appropriate for SCD. This has implications for developing cost-effective management strategies (if pulmonary function testing does not add diagnostic value – it may not be indicated). Understanding the mechanisms that underlie non-asthmatic SCD wheezing will be important for the development of targeted therapies.

We have demonstrated that wheezing and asthma are independent risk factors for increased SCD morbidity in children and adults with SCD. Only wheezing was associated with increased risk of acute chest syndrome. Prospective trials are necessary to determine if control of wheezing reduces the frequency of pain or acute chest syndrome in individuals with SCD.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following contributors: Robert C Strunk MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Gary Yu MS MPH: analysis and interpretation of the data (Mr. Yu received financial compensation for his support).

Footnotes

Author contribution statement

JAG conceived the study, acquired the data, supervised data collection and drafted the manuscript. JAG, AC, JW, RH, MRD and LDR were responsible for the full content of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data and have no competing interests to report. JAG takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

References

- An P, Barron-Casella EA, Strunk RC, Hamilton RG, Casella JF, DeBaunm MR. Elevation of IgE in children with sickle cell disease is associated with doctor diagnosis of asthma and increased morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1440–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anim SO, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma morbidity and treatment in children with sickle cell disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5:635–645. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaudin F, Strunk RC, Kamdem A, Arnaud C, An P, Torres M, Delacourt C, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with acute chest syndrome, but not with an increased rate of hospitalization for pain among children in France with sickle cell anemia: a retrospective cohort study. Haematologica. 2008;93:1917–1918. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Moinuddin A, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma and acute chest in sickle-cell disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2004;38:229–232. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with acute chest syndrome and pain in children with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2006;108:2923–2927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-011072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with increased mortality in individuals with sickle cell anemia. Haematologica. 2007;92:1115–1118. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RT, Madadi A, Blinder MA, Debaun MR, Strunk RC, Field JJ. Recurrent, severe wheezing is associated with morbidity and mortality in adults with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology. 2011;86:756–761. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field JJ, DeBaun MR. Asthma and sickle cell disease: two distinct diseases or part of the same process? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:45–53. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field JJ, Stocks J, Kirkham FJ, Rosen CL, Dietzen DJ, Semon T, Kirkby J, Bates P, Seicean S, DeBaun MR, Redline S, Strunk RC. Airway hyperresponsiveness in children with sickle cell anemia. Chest. 2011;139:563–568. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassberg J, Spivey JF, Strunk R, Boslaugh S, DeBaun MR. Painful episodes in children with sickle cell disease and asthma are temporally associated with respiratory symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/oncology. 2006;28:481–485. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000212968.98501.2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight-Madden JM, Forrester TS, Lewis NA, Greenough A. Asthma in children with sickle cell disease and its association with acute chest syndrome. Thorax. 2005;60:206–210. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.029165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumbourlis AC, Hurlet-Jensen A, Bye MR. Lung function in infants with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1997;24:277–281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199710)24:4<277::aid-ppul6>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumbourlis AC, Zar HJ, Hurlet-Jensen A, Goldberg MR. Prevalence and reversibility of lower airway obstruction in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2001;138:188–192. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumbourlis AC, Lee DJ, Lee A. Longitudinal changes in lung function and somatic growth in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2007;42:483–488. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumbourlis AC, Lee DJ, Lee A. Changes in lung function in children with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2009;180:377–378. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.180.4.377. 377; author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong MA, Dampier C, Varlotta L, Allen JL. Airway hyperreactivity in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;131:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CR. Asthma management: reinventing the wheel in sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology. 2009;84:234–241. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandedkar SD, Feroah TR, Hutchins W, Weihrauch D, Konduri KS, Wang J, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR, Hillery CA, Pritchard KA. Histopathology of experimentally induced asthma in a murine model of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2008;112:2529–2538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newaskar M, Hardy KA, Morris CR. Asthma in sickle cell disease. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:1138–1152. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordness ME, Lynn J, Zacharisen MC, Scott PJ, Kelly KJ. Asthma is a risk factor for acute chest syndrome and cerebral vascular accidents in children with sickle cell disease. Clin Mol Allergy. 2005;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbek OY, Malbora B, Sen N, Yazici AC, Ozyurek E, Ozbek N. Airway hyperreactivity detected by methacholine challenge in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2007;42:1187–1192. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perin RJ, McGeady SJ, Travis SF, Mansmann HC., Jr Sickle cell disease and bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1983;50:320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard KA, Jr, Ou J, Ou Z, Shi Y, Franciosi JP, Signorino P, Kaul S, Ackland-Berglund C, Witte K, Holzhauer S, Mohandas N, Guice KS, Oldham KT, Hillery CA. Hypoxia-induced acute lung injury in murine models of sickle cell disease. American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2004;286:L705–L714. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard KA, Feroah TR, Nandedkar SD, Holzhauer SL, Hutchins W, Schulte ML, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR, Hillery CA. Effects of Experimental Asthma on Inflammation and Lung Mechanics in Sickle Cell Mice. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2012;46:389–396. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0097OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen N, Kozanoglu I, Karatasli M, Ermis H, Boga C, Eyuboglu FO. Pulmonary function and airway hyperresponsiveness in adults with sickle cell disease. Lung. 2009;187:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9141-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk RC, Brown MS, Boyd JH, Bates P, Field JJ, DeBaun MR. Methacholine challenge in children with sickle cell disease: a case series. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2008;43:924–929. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester KP, Patey RA, Broughton S, Rafferty GF, Rees D, Thein SL, Greenough A. Temporal relationship of asthma to acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2007a;42:103–106. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester KP, Patey RA, Rafferty GF, Rees D, Thein SL, Greenough A. Airway hyperresponsiveness and acute chest syndrome in children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2007b;42:272–276. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichinsky EP, Styles LA, Colangelo LH, Wright EC, Castro O, Nickerson B. Acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: clinical presentation and course. Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 1997;89:1787–1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]