Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether additional catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) improves long-term quality of life (QOL) compared with standard treatment with anticoagulation and compression stockings alone in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Design

Open-label randomised controlled trial.

Setting

19 Hospitals in the Norwegian southeastern health region.

Participants

Patients (18–75 years) with a high proximal DVT, symptoms <21 days and no increased risk of bleeding were eligible. 189 of 209 recruited patients completed 24 months of follow-up.

Interventions

Participants were randomised to additional CDT with alteplase for 1–4 days or to standard treatment only with 6 months of anticoagulation and 24 months of compression stockings.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Planned secondary outcome measures included QOL as assessed with the generic instrument EQ-5D and the disease-specific instrument VEINES-QOL/Sym. Primary outcome measure was post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) after 24 months.

Results

After 24 months there were no differences in QOL between the additional CDT and standard treatment arms; mean difference for the EQ-5D index was 0.04 (95% CI −0.10 to 0.17), for the VEINES-QOL score 0.2 (95% CI −2.8 to 3.0) and for the VEINES-Sym score 0.5 (95% CI −2.4 to 3.4; p values>0.37). Independent of treatment arms, patients with PTS had poorer outcomes than patient without PTS; mean difference for EQ-5D was 0.09 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.15), for VEINES-QOL score 8.6 (95% CI 5.9 to 11.2) and for VEINES-Sym score 9.8 (95% CI 7.3 to 12.3; p values<0.001).

Conclusions

QOL did not differ between patients treated with additional CDT compared with standard treatment alone. Patients who developed PTS reported poorer QOL and more symptoms than patients without PTS. QOL should be included as an outcome measure in clinical studies on patients at risk of PTS.

Trial registration

Article summary.

Article focus

Assessment of quality of life (QOL) may provide meaningful information not captured by clinical scores and other traditional health outcome measures.

Additional catheter-directed thrombolysis for proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) improves long-term clinical outcome by reducing post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) and is likely to be a cost-effective alternative to standard treatment alone.

Our objective was to investigate whether additional thrombolysis also improves long-term QOL compared with standard treatment alone.

Key messages

QOL did not differ between patients allocated thrombolytic therapy compared with control patients who received standard anticoagulation and compression stockings only.

Patients who developed PTS had poorer generic and disease-specific QOL scores compared with patients without PTS.

QOL assessment should be among the long-term outcome measures in clinical research on patients who are at risk of developing PTS.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A robust study design where patient-reported QOL was assessed using validated generic and disease-specific instruments within the setting of a multicentre open-label randomised controlled trial.

The study was designed to detect a difference in the frequency of PTS between the two treatment arms and may have been underpowered to detect a clinically meaningful difference in QOL. Other possible explanations include a relatively small effect on the reduction in PTS and the smaller proportion presenting with iliofemoral DVT relative to infrainguinal DVT.

More frequent study visits and longitudinal assessments of QOL would have allowed for better explanatory analyses, and may have added to the interpretation of clinically meaningful differences in the disease-specific QOL scores.

Introduction

Following standard treatment including anticoagulation and compression stockings, at least one in four are at risk of developing a post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) after suffering a proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT), that is, DVT in the popliteal vein or above.1–3 PTS is characterised by persistent pain, heaviness, swelling and deterioration of the skin. Previously, in the CaVenT study, we have shown that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) in patients with a high proximal DVT localised in the mid-thigh level or above, and a low risk of bleeding, reduced the frequency of PTS from 56% to 41% (p=0.047) after 2 years and that CDT is likely to be a cost-effective alternative to standard treatment.4 5 However, as PTS is a chronic condition associated with substantial morbidity and with no healing treatment options, assessment of both generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life (QOL), including the impact on health and daily functioning, may provide meaningful information not captured by clinical scores and other traditional health outcome measures. Development of PTS has been shown to be a principal determinant of QOL following DVT of the lower limb; however, there is currently no gold standard for the PTS diagnosis.6 We aimed at investigating whether additional CDT for a high proximal DVT improved long-term QOL compared with standard treatment alone.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients were recruited as part of the CaVenT study, an open randomised controlled trial (RCT), from 19 hospitals within the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, which serves a population of 2.6 million people. Patients aged 18–75 years with a first-time objectively verified acute high proximal DVT, defined as thrombus in mid-thigh level or higher and with a low risk of bleeding, were eligible for inclusion if symptoms had lasted <21 days. Complete eligibility criteria and trial profile have been reported previously.5 7 Patients were randomly assigned, using sealed numbered envelopes, to standard treatment with at least 6 months of anticoagulation and compression stockings for 24 months or to CDT with alteplase for 1–4 days in addition to standard treatment; the treatment strategies have previously been reported in detail.5 8 Prior to treatment allocation, written informed consent was obtained by the local trial site investigator.

Variables and instruments

Long-term QOL

After 6 and 24 months of follow-up the patients completed a self-reporting questionnaire including the validated Norwegian versions of the generic instrument EQ-5D (http://www.euroqol.org) and the disease-specific QOL instrument VEINES-QOL/Sym.9 10 The VEINES-QOL/Sym comprises 26 items regarding problems of the lower limbs.4 The instrument measures symptoms, limitations in daily activity and psychological impact during the previous 4 weeks and change over the past year. Responses are rated on 2-point to 7-point descriptive scales, and two summary scores are computed. The VEINES-QOL summary score assesses QOL, and the VEINES-Sym score is a subscale that measures symptom severity only. Higher scores represent better QOL and/or fewer symptoms, and a difference or change of ≥4 points has been suggested to represent a clinically meaningful difference.10

The EQ-5D is a preference-based generic instrument for describing and valuing QOL, and is a widely used health measure outcome in clinical trials and cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses. This descriptive classification system comprises five items: mobility, self-care, activity, pain and anxiety; each with the three levels reflecting the patient's status that particular day. The scoring provides a single number/health status index ranging from 0 (dead) to 1 (best possible health). A difference or change in this index of ≥0.08 is likely to represent a clinically meaningful difference.11 12

Assessment of PTS

In the absence of a gold standard for a PTS diagnosis, the Villalta score has been recommended for PTS assessment in clinical trials.13 This score includes the five patient-rated symptoms: pain, cramps, heaviness, paraesthesia and pruritus; and the six clinician-rated signs: oedema, skin induration, hyperpigmentation, pain during calf compression, venous ectasia and redness. Each sign or symptom is rated as 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate) or 3 (severe), and summed to produce a total score, where less than 5 indicates no PTS, 5–14 indicates mild or moderate PTS and 15 or more (or presence of venous ulcer) indicates severe PTS.

Statistical analysis and sample size

Health-related QOL was among the prespecified secondary outcomes of the CaVenT study, while the primary outcome of PTS after 2 years was the basis for the sample size calculation.7 For all patients, an EQ-5D summary index was calculated based on values from a Danish population as there was no Norwegian algorithm.14 Scores for VEINES-QOL and VEINES-Sym were computed using standard scoring algorithms obtained from the authors.10 Statistical analyses were by intention to treat. Any ineligible patients mistakenly included were excluded. Missing outcome data because of withdrawal of consent or death from cancer or other causes not related to CDT or anticoagulation were assumed to be missing independently of treatment received and were not included in the analyses.5 When comparing dichotomous variables between groups, a two-sided χ2 test was used. Normal distribution was tested visually using plots, followed by comparing non-normally distributed continuous variables between independent groups with a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. Findings with p values less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS V.18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

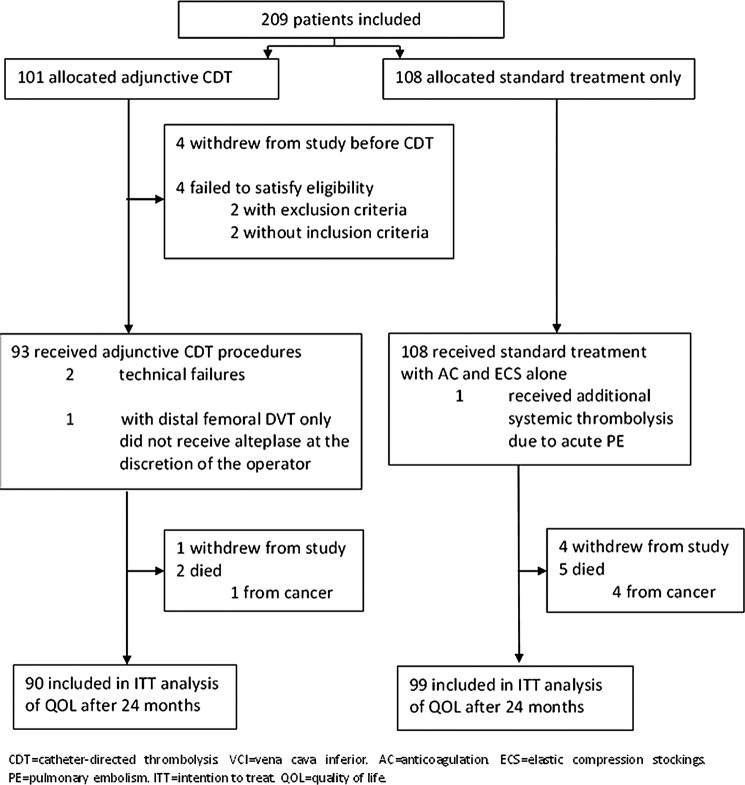

In total, 209 patients with a high proximal DVT were recruited and randomised to additional CDT or to standard treatment alone during 2006–2009. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of 189 patients with complete 2 years of follow-up included in the present analysis; 90 in the CDT group and 99 controls. Mean age was 51.5 years (SD 15.8) and 70 (37%) participants were female. Mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis and start of the treatment was 6.6 days (SD 4.6). Most baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, including VEINES-QOL/Sym and EQ-5D scores, were fairly equally distributed between the two treatment groups. Figure 1 presents details on the study participants and the complete trial profile.5

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Adjunctive catheter-directed thrombolysis (n=90) | Standard treatment only (n=99) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Age (years) | 53.3 (15.7) | 50.0 (15.8) |

| Women | 32 (35.6) | 38 (38.4) |

| Duration of symptoms of acute DVT (days) | 6.4 (4.4) | 6.8 (4.8) |

| EQ-5D index | 0.46 (0.39) | 0.63 (0.99) |

| VEINES-QOL score | 50.2 (9.3) | 50.1 (10.7) |

| VEINES-Sym score | 50.4 (9.3) | 49.5 (10.7) |

| No risk factor for venous thrombosis | 31 (34.4) | 26 (26.3) |

| Transient risk factors for venous thrombosis | ||

| Surgery previous 3 months | 15 (16.7) | 13 (13.1) |

| Trauma previous 3 months | 10 (11.1) | 15 (15.2) |

| Short-term immobility | 20 (22.2) | 19 (19.2) |

| Infection previous 6 weeks | 6 (6.7) | 9 (9.1) |

| Pregnancy previous 3 months | 5 (5.6) | 3 (3.0) |

| Hormonal replacement therapy | 4 (4.4) | 6 (6.1) |

| Oral contraceptive pill | 3 (3.3) | 11 (11.1) |

| Permanent risk factors for venous thrombosis | ||

| Previous venous thrombosis | 9 (10.0) | 9 (9.1) |

| Cancer | 3 (3.3) | 1 (1.0) |

| Obesity | 9 (10.0) | 11 (11.1) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.0) |

| First degree relative with venous thrombosis | 9 (10.0) | 13 (13.1) |

| Two risk factors for venous thrombosis | 26 (28.9) | 18 (18.2) |

| Three risk factors for venous thrombosis | 10 (11.1) | 14 (14.1) |

| Thrombophilia | ||

| Heterozygous F5 6025 polymorphism | 23 (25.6) | 22 (22.2) |

| Homozygous F5 6025 polymorphism | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.0) |

| Other thrombophilic factor(s) | 15 (16.7) | 13 (13.1) |

Data are mean (SD) or n (%).

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; QOL, quality of life.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

There were no differences between the two treatment groups in mean generic QOL scores, disease-specific QOL scores or symptom severity score after 24 months of follow-up (table 2). Both VEINES-QOL and VEINES-Sym scores obtained at 6 months of follow-up were higher in the CDT arm compared with control patients (p=0.048 and p=0.016, respectively), however, the mean differences of 2.4 and 3.2 points, respectively, were below the ≥4 points cut-off for a clinically meaningful difference. The 6 months’ EQ-5D score did not differ between the treatment groups. After 24 months of follow-up, 57 (63.3%) patients allocated additional CDT reported to wear compression stocking daily versus 51 (51.5%) controls. In the CDT arm 10 (11.1%) experienced a recurrent venous thromboembolism and 4 (4.4%) were diagnosed with cancer. The corresponding numbers among control arm patients were 18 (18.2%) and 7 (7.1%), respectively.5

Table 2.

Generic and disease-specific quality of life and symptom severity according to treatment allocation

| Additional catheter-directed thrombolysis (n=90) | Standard treatment only (n=99) | Mean difference | p Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 months | |||||

| Generic QOL | EQ-5D | 0.80 (0.746 to 0.849) | 0.84 (0.807 to 0.875) | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.17) | 0.705 |

| Disease-specific QOL | VEINES-QOL | 50.1 (47.9 to 52.3) | 49.9 (48.0 to 51.8) | 0.2 (−2.8 to 3.0) | 0.595 |

| VEINES-Sym | 50.3 (48.0 to 52.5) | 49.8 (47.9 to 51.6) | 0.5 (−2.4 to 3.4) | 0.368 | |

| 6 months | |||||

| Generic QOL | EQ-5D | 0.82 (0.780 to 0.856) | 0.81 (0.777 to 0.852) | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.06) | 0.893 |

| Disease-specific QOL | VEINES-QOL | 51.3 (49.2 to 53.4) | 48.9 (46.8 to 50.9) | 2.4 (−0.5 to 5.3) | 0.048 |

| VEINES-Sym | 51.7 (49.8 to 53.7) | 48.5 (46.4 to 50.6) | 3.2 (0.4 to 6.1) | 0.016 | |

Data are mean values (95% CI).

*Mann Whitney U test.

QOL, quality of life.

Independent of treatment allocation, the mean VEINES-QOL and VEINES-Sym scores were lower in patients who developed PTS compared with patients without PTS at both 6 and 24 months of follow-up (p values <0.001; table 3). The mean differences were 6 points after 6 months, and increased to 8.6 and 9.8 points, respectively, after 24 months. The mean EQ-5D index was 0.09 points lower in PTS patients at 24 months of follow-up (p<0.001); however, there was no mean difference after 6 months. When looking at the PTS cases only at 24 months of follow-up the three scores did not differ between the two treatment groups (p value >0.8, data not shown).

Table 3.

Generic and disease-specific quality of life and symptom severity according to PTS development

| PTS (n=92) | No PTS (n=97) | Mean difference | p Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 months | |||||

| Generic QOL | EQ-5D | 0.77 (0.730 to 0.819) | 0.86 (0.823 to 0.903) | 0.09 (0.03 to 0.15) | <0.001 |

| Disease-specific QOL | VEINES-QOL | 45.6 (43.4 to 47.9) | 54.2 (52.8 to 55.6) | 8.6 (5.9 to 11.2) | <0.001 |

| VEINES-Sym | 45.0 (42.7 to 47.2) | 54.8 (53.5 to 56.0) | 9.8 (7.3 to 12.3) | <0.001 | |

| 6 months | |||||

| Generic QOL | EQ-5D | 0.80 (0.770 to 0.837) | 0.82 (0.788 to 0.869) | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.28) | 0.062 |

| Disease-specific QOL | VEINES-QOL | 46.8 (44.6 to 49.0) | 53.0 (51.3 to 54.7) | 6.2 (3.4 to 9.09) | <0.001 |

| VEINES-Sym | 46.9 (44.6 to 49.1) | 53.0 (51.4 to 54.6) | 6.1 (3.4 to 8.9) | <0.001 | |

Data are mean values (95% CI).

*Mann Whitney U test.

PTS, post-thrombotic syndrome; QOL, quality of life.

Analysing individual items concerning problems with mobility (EQ-5D) and limitations in daily activities at home, work or during leisure time (VEINES-QOL) there were no differences between the two treatment groups; however, patients with PTS reported more problems and limitations than patients without PTS (data not shown).

The proportions of patients who reported clinically meaningful changes over time during the 6–24 months of follow-up did not differ between the two treatment groups with regard to the two QOL scores, and the majority of patients reported no QOL change (table 4). In both groups one in five patients reported worsening of the Sym score, and 32% of control patients reported improved symptom severity compared with 16% treated with CDT (p=0.029).

Table 4.

Changes in generic and disease-specific quality of life and symptom severity during 6–24 months of follow-up*

| Additional catheter-directed thrombolysis (n=90) |

Standard treatment only (n=99) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | p Value† | |

| Generic QOL | |||||

| EQ-5D improved | 15 | 16.7 (10.0 to 24.4) | 24 | 24.5 (16.6 to 33.4) | 0.233 |

| EQ-5D worsened | 22 | 24.4 (16.4 to 34.1) | 16 | 16.3 (9.9 to 24.4) | |

| Disease-specific QOL | |||||

| VEINES-QOL improved | 17 | 19.5 (11.8 to 28.0) | 27 | 27.3 (19.2 to 36.7) | 0.462 |

| VEINES-QOL worsened | 19 | 21.8 (13.6–30.4) | 19 | 19.2 (12.3 to 27.8) | |

| VEINES-Sym improved | 14 | 15.9 (9.1 to 24.2) | 32 | 32.3 (23.7 to 42.0) | 0.029 |

| VEINES-Sym worsened | 20 | 22.7 (14.5 to 31.7) | 21 | 21.2 (14.0 to 30.1) | |

| PTS (n=92) | No PTS (n=97) | ||||

| Generic QOL | |||||

| EQ-5D improved | 15 | 16.5 (9.8 to 24.9) | 24 | 24.7 (16.9 to 34.0) | 0.041 |

| EQ-5D worsened | 25 | 27.5 (18.8 to 36.9) | 13 | 13.4 (7.7 to 21.3) | |

| Disease-specific QOL | |||||

| VEINES-QOL improved | 21 | 23.3 (15.1 to 32.2) | 23 | 24.0 (16.1 to 32.9) | 0.017 |

| VEINES-QOL worsened | 26 | 28.9 (19.8 to 38.1) | 12 | 12.5 (6.9 to 20.1) | |

| VEINES-Sym improved | 20 | 22.0 (14.2 to 31.0) | 26 | 27.1 (18.7 to 36.3) | 0.017 |

| VEINES-Sym worsened | 28 | 30.8 (21.7 to 40.4) | 12 | 13.5 (7.7 to 21.3) | |

*A meaningful change was defined as ≥4 points for VEINES-QOL/Sym scores and ≥0.08 for the EQ-5D index; improvement or worsening below this was registered as no change.

†χ2 test.

QOL, quality of life.

Correspondingly, when comparing proportions with meaningful changes in the three different scores during the follow-up in patients with and without development of PTS independent of treatment allocation, the EQ-5D and VEINES-QOL scores worsened in nearly 30% of patients with PTS compared with 13% of patients who did not develop PTS (p=0.041 and p=0.017, respectively; table 4). Finally, 31% patients with PTS reported worsening of the Sym score compared with 14% of patients without PTS (p=0.017).

Discussion

We have previously shown that after a high proximal DVT additional CDT reduces the frequency of PTS.5 Nevertheless, in the current report we found no differences in long-term QOL between patients treated with additional CDT compared with patients who received standard treatment with anticoagulation and compression stockings alone. However, patients who developed PTS after 24 months reported poorer QOL with both EQ-5D and VEINES-QOL, and more symptoms on Sym score compared with patients without PTS. This finding is in line with other reports, and the VEINES-QOL/Sym scores were in similar range as previously reported in DVT populations.6 15–17

To our knowledge this is the first study to investigate QOL after CDT in a well-designed manner using validated QOL instruments and PTS assessment. We have recently in a retrospective study of 71 patients previously treated with CDT shown that VEINES-QOL/Sym scores were poorer in patients with established PTS compared with no PTS (median) 6 years after the index DVT, and poorer in patients compared with a control group without previous DVT.17 Another retrospective study of corresponding size found improved QOL and less post-thrombotic symptoms in patients treated with CDT compared with similar patients treated with anticoagulation only; however, this study did not use a disease-specific QOL instrument or a validated assessment of PTS.18 This finding was not supported in our RCT, and long-term QOL may not represent a significant secondary efficacy outcome after CDT.

The baseline scores were obtained within 1–2 days following the verification of the acute DVT, and the low EQ-5D scores are likely to reflect patients’ medical emergency situation at that time point. The items of the VEINES instrument are concerned with ‘the last 4 weeks’ and mean symptom duration among study participants was only 6–7 days and, as indicated by the relatively better scores, the VEINES-QOL/Sym baseline results are likely to reflect a longer period including time before symptom onset. Finally, QOL is a more appropriate outcome for chronic conditions, and together with our lack of more frequent study visits and longitudinal assessments, we did not include baseline scores in our analyses.

The finding that more control patients reported a meaningful improvement in the Sym score during the follow-up than patients treated with CDT, should be interpreted with caution as the 6-month Sym score was higher in the CDT arm, though this difference did not reach a meaningful difference of at least 4 points.

We regard our study population to be representative and the CDT procedure to be applicable in a clinical setting.5 However, due to the open label design, bias in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as QOL cannot be excluded, and it is uncertain in what direction such bias would impact the results. As our eligibility criteria allowed for study participants to enrol with up to 21 days of symptoms, this meant that patients with subacute DVT, that is, more than 14 days of symptoms, may have entered the study and possibly contributed to the overall high PTS frequency and lack of treatment group differences in the QOL scores.19 However, as the mean symptom duration was less than 7 days and only 15 patients (hereunder 8 controls) had more than 14 days of symptom, we find this unlikely. Finally, two ongoing RCTs; the American ATTRACT study and the DUTCH CAVA trial, will provide additional data to the field of QOL after CDT treatment (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT 00790335 and NCT 00970619).

The Villalta scale has been validated and recommended for assessment of PTS,13 20 however, as no gold standard exists and a relatively high frequency of PTS was found in both treatment arms, concerns have been raised about the clinical benefit of CDT as shown in the CaVenT study.5 21 The current findings of poorer QOL in those who developed PTS, as obtained within an appropriately designed RCT, underpin our perception that the 15% absolute reduction in PTS as assessed with the Villalta scale and shown in CaVenT, does represent a clinically meaningful effect of additional CDT.5

It has been recommended to include QOL as part of the long-term follow-up assessment of patients at risk of PTS,6 and a recent review “recommend(s) that the Villalta score combined with a venous disease-specific QOL questionnaire be considered as the ‘gold standard’ for the diagnosis and classification of PTS.”22 The VEINES questionnaire would be a candidate, but such a combination must be validated in appropriately designed studies and take into account the apparent overlap between the Villalta score and the VEINES-scores; all items in the Sym score are covered in the QOL score, 2/3 of Sym items are covered in Villalta and 1/4 of the QOL items are covered in Villalta. Finally, 5 of 11 items in Villalta score, that is, the symptom rating, are in fact PROs, and combining with another patient PRO instrument should seek to avoid repeat assessment.

The generic instrument EQ-5D showed a clinically meaningful and statistically significant poorer QOL measure in patients who developed PTS, indicating that this preference-based questionnaire can be included in studies on PTS and thereby allowing analyses on utilities and cost-effectiveness for decision-making.23 However, the sample size was powered to detect a 15% reduction in PTS after additional CDT, not improvement in QOL, which was among the secondary outcome measures. Accordingly, the negative finding in terms of no difference in QOL between the treatment arms, may relate to the sensitivity of the instruments, the prevalence of PTS and the lack of power to detect a statistically significant difference. Finally, the VEINES scores differed significantly between patients with PTS versus no PTS, and the magnitude of the mean difference was 6 points or higher. This has been reported to represent meaningful differences, but a well-established definition or cut-off for a clinically meaningful difference in VEINES scores is lacking, and also this limitation must be taken into account when interpreting the results.10

In conclusion, there was no difference in long-term QOL between patients with a high proximal DVT treated with additional CDT compared with those treated with anticoagulation and compression therapy alone. Patients who developed PTS reported poorer QOL and more symptoms than patients without PTS. This is in line with previous reports, and supports the use of QOL as an outcome measure in clinical research on patients who are at risk of PTS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all study participants and study collaborators; without their contributions the CaVenT study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: TE participated in the design of study, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, obtaining funding; HSW participated in acquisition of the data, interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript; AKK participated in interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript; YH participated in acquisition of the data and critical revision of the manuscript; NEK and PMS participated in the design of study, acquisition of the data, critical revision of the manuscript, obtaining funding.

Funding: This work was funded by South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Research Council of Norway, University of Oslo and Oslo University Hospital, and the Unger-Vetlesen Medical Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Medicines Agency, and was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov with the unique trial identifier NCT00251771..

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Unpublished data from the CaVenT study are available to TE, YH, NEK and PMS through authorised access to the research server at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål.

References

- 1.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Below-knee elastic compression stockings to prevent the post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:249–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandjes DP, Buller HR, Heijboer H, et al. Randomised trial of effect of compression stockings in patients with symptomatic proximal-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1997;349:759–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e419S–94S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enden T, Resch S, White C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of additional catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2013;11:1032–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enden T, Haig Y, Klow NE, et al. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:1105–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enden T, Sandvik L, Klow NE, et al. Catheter-directed venous thrombolysis in acute iliofemoral vein thrombosis-the CaVenT Study: rationale and design of a multicenter, randomized, controlled, clinical trial (NCT00251771). Am Heart J 2007;154:808–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enden T, Klow NE, Sandvik L, et al. Catheter-directed thrombolysis vs. anticoagulant therapy alone in deep vein thrombosis: results of an open randomized, controlled trial reporting on short-term patency. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:1268–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enden T, Garratt AM, Klow NE, et al. Assessing burden of illness following acute deep vein thrombosis: data quality, reliability and validity of the Norwegian version of VEINES-QOL/Sym, a disease-specific questionnaire. Scand J Caring Sci 2009;23:369–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamping DL, Schroter S, Kurz X, et al. Evaluation of outcomes in chronic venous disorders of the leg: development of a scientifically rigorous, patient-reported measure of symptoms and quality of life. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:410–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1523–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn SR, Partsch H, Vedantham S, et al. Definition of post-thrombotic syndrome of the leg for use in clinical investigations: a recommendation for standardization. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:879–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittrup-Jensen KU, Lauridsen J, Gudex C, et al. Generation of a Danish TTO value set for EQ-5D health states. Scand J Public Health 2009;37:459–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn SR, Ducruet T, Lamping DL, et al. Prospective evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with deep venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1173–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broholm R, Sillesen H, Damsgaard MT, et al. Postthrombotic syndrome and quality of life in patients with iliofemoral venous thrombosis treated with catheter-directed thrombolysis. J Vasc Surg 2011;54:18S–25S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghanima W, Kleven IW, Enden T, et al. Recurrent venous thrombosis, post-thrombotic syndrome and quality of life after catheter-directed thrombolysis in severe proximal deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:1261–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comerota AJ. Quality-of-life improvement using thrombolytic therapy for iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2002;3(Suppl 2):S61–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vedantham S, Grassi CJ, Ferral H, et al. Reporting standards for endovascular treatment of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009;20:S391–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahn SR. Measurement properties of the Villalta scale to define and classify the severity of the post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:884–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann LV, Kuo WT. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute DVT. Lancet 2012;379:3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soosainathan A, Moore HM, Gohel MS, et al. Scoring systems for the post-thrombotic syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2012;57:254–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd edn 2006 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.