Abstract

Objective

To review the literature on educational interventions to improve prescribing and identify educational methods that improve prescribing competency in both medical and non-medical prescribers.

Design

A systematic review was conducted. The databases Medline, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), EMBASE and CINAHL were searched for articles in English published between January 1990 and July 2013.

Setting

Primary and secondary care.

Participants

Medical and non-medical prescribers.

Intervention

Education-based interventions to aid improvement in prescribing competency.

Primary outcome

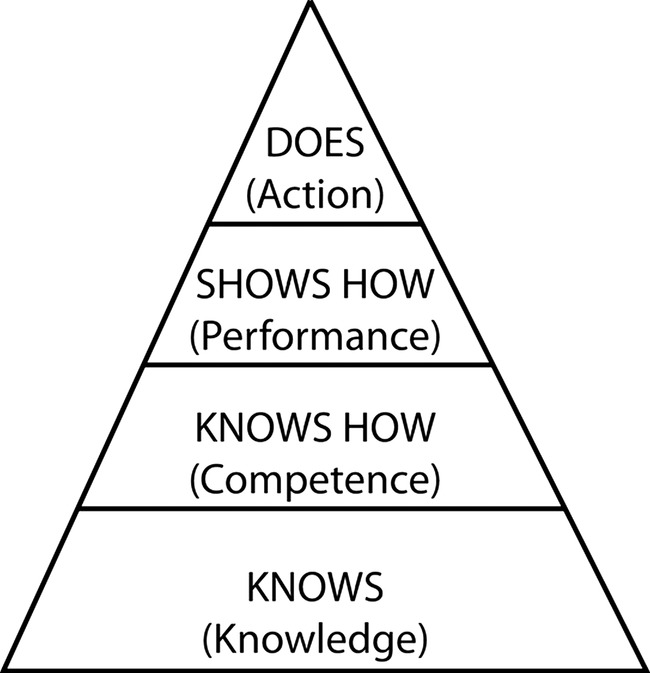

Improvements in prescribing competency (knows how) or performance (shows how) as defined by Miller's competency model. This was primarily demonstrated through prescribing examinations, changes in prescribing habits or adherence to guidelines.

Results

A total of 47 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Studies were categorised by their method of assessment, with 20 studies assessing prescribing competence and 27 assessing prescribing performance. A wide variety of educational interventions were employed, with different outcome measures and methods of assessments. In particular, six studies demonstrated that specific prescribing training using the WHO Guide to Good Prescribing increased prescribing competency in a wide variety of settings. Continuing medical education in the form of academic detailing and personalised prescriber feedback also yielded positive results. Only four studies evaluated educational interventions targeted at non-medical prescribers, highlighting that further research is needed in this area.

Conclusions

A broad range of educational interventions have been conducted to improve prescribing competency. The WHO Guide to Good Prescribing has the largest body of evidence to support its use and is a promising model for the design of targeted prescribing courses. There is a need for further development and evaluation of educational methods for non-medical prescribers.

Keywords: EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, THERAPEUTICS

Article summary.

Article focus

Prescribing competencies that cover both medical and non-medical prescribers have been developed internationally.

A review of the educational interventions designed to improve prescribing competencies will help to ensure evidence-based interventions are used to develop competent medical and non-medical prescribers.

Key messages

The WHO Guide to Good Prescribing has the largest body of evidence supporting its use to improve prescribing competencies internationally.

Few studies have focused on educational interventions for non-medical prescribers.

There is a need for further development and evaluation of educational methods for non-medical prescribers.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Timely systematic review considering international developments regarding non-medical prescribers.

Difficult to generalise findings considering different methods of assessments used.

Limited to publications in English only.

Introduction

Prescribing, a complex process involving the initiation, monitoring, continuation and modification of medication therapy,1 demands a thorough understanding of clinical pharmacology as well as the judgement and ability to prescribe rationally for the benefit of patients.2 The rational prescribing of medicines as defined by the WHO is “the situation in which patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements for a sufficient length of time, with the lowest cost to them and their community.”3 Equipping prescribers with skills for rational prescribing is essential.

The diversity of skills required for good prescribing present a major challenge for the development of educational programmes. Adding to this complexity is the extension of prescribing rights to non-medical healthcare professionals such as optometrists, nurses and pharmacists. Potential benefits of non-medical prescribing have been argued to include improved continuity of care and access to medicines, better allocation of human resources, increased patient convenience and less fragmentation of care1; however, the process of prescribing is considered high-risk and error-prone.2 Hence competent prescribing is paramount to patient safety. Poor prescribing can be illustrated by prescription errors, under or overprescribing or inappropriate and irrational prescribing.2 4 Junior prescribers appear most prone to prescribing errors, yet are expected to perform a significant prescribing role.5–8 Although many prescribing errors are unintentional, studies have shown that the prescribing performance of interns and medical students is poor, partly because of inadequate training.9 10 Little is known however about non-medical prescribing practices and rates of prescription errors. Research into non-medical prescribing has mainly been confined to self-report measures such as questionnaire and interview surveys.11 Although one UK study indicated that nurses’ prescribing decisions were generally clinically appropriate, a large proportion did not display some prescribing competencies, for example, taking patients’ medicines history and allergy status.12

Traditionally assessment of education was based on knowledge tests; however, it is recognised today that knowledge alone is insufficient to predict performance in practice.13 This has led to the introduction of competency-based education, focusing on developing knowledge, judgement and skills.13 14 Miller13 proposed a four-staged competency assessment model beginning with assimilation of pure knowledge, progressing to development of real performance in practice (figure 1). Mucklow et al15 provides further examples of assessing prescribing competence based on Miller's model and its importance for the healthcare profession. Such developments have led the National Prescribing Centre in the UK and the NPS MedicineWise (Quality Use of Medicines service agency for Australia's National Medicines Policy) to produce a core competency framework for all prescribing, both medical and non-medical.16 17 Although a number of recommendations for prescribing education to ensure competency have been introduced,15 there is little evidence and detail as to how these competencies could actually be achieved.18

Figure 1.

Miller's framework for clinical assessment.13

Three systematic reviews of interventions to improve prescribing were published since 2009.19–21 One focused on medical students and junior doctors,20 while another was an update of two previous reviews investigating the effectiveness of different types of interventions on improving prescribing.19 The most recent review focuses on the hospital setting with an emphasis on new prescribers who were less than 2 years postgraduation.21 Although all new prescribers were included in this review, little was discussed regarding non-medical prescribers. The Cochrane collaboration has also comprehensively evaluated the use of audit and feedback to improve prescribing.22 23 The focus of this review is on prescribing competencies and its assessment, based on the higher stages of Miller's model (competency and performance). This comprises practical aspects of prescription-writing as well as therapeutic decision-making, ensuring that rational, evidence-based therapy-selection is made based on patients’ requirements and evaluation of their capacity to comply with a prescribed medicine).

This review aimed to examine the literature on educational interventions designed to develop and improve patient-focused prescribing competency in both medical and non-medical prescribers.

Method

Search strategy

MEDLINE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), EMBASE and CINAHL were searched using the key words: (‘prescription$’ OR ‘prescriber$’ OR ‘prescribing’) AND (‘education’ OR ‘curriculum’ OR ‘course$’ OR ‘training’ OR ‘intervention$’) AND (‘drug$’ OR ‘medication$’ or ‘medication therapy management’) AND (‘clinical competence’ OR ‘competency’ OR ‘competency assessment’). The search terms were mapped onto Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in Medline and EMBASE and carried through other database as key search terms. The search was limited to articles published in English from January 1990 to July 2013 (see online supplementary appendices 1–4).

Study selection

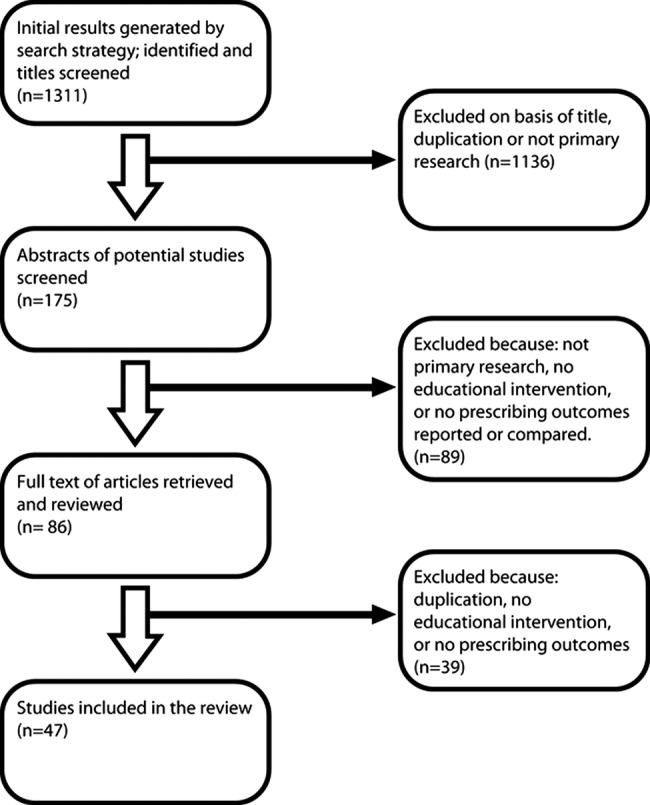

Citations generated by the search strategy were screened by all authors for relevance and eligibility. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were reviewed to determine satisfaction of inclusion criteria. The screening process was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines24 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of search strategy and study selection based on PRISMA guidelines.24

The target population was medical or non-medical prescribers. All study designs were considered for this review. Studies were included if they were original research articles, had an educational intervention, and at least one outcome measure of prescribing competency demonstrated through prescribing examinations which evaluated the application of knowledge to patient cases or scenarios, changes in prescribing habits or adherence to guidelines. Studies were excluded if they only measured theoretical knowledge of pharmacology and therapeutics or studied an intervention involving drug utilisation evaluation primarily using audit and feedback without a focus on the educational intervention, as these were often targeted towards cost-effectiveness and contains a large body of literature that has been previously reviewed by the Cochrane collaboration.22 23 Systematic reviews, letters, meeting reports and opinion pieces were also excluded. The review was not restricted to any country.

Two authors (GK and JP) reviewed the titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved in the search to assess relevance. Discussions were conducted between the four authors to exclude studies which did not meet the inclusion criteria, and this continued until consensus was achieved regarding study selection.

Data extraction and analysis

Study location, design, characteristics of the study population, description of the education intervention, outcomes measured and results were extracted by GK and JP.

Results

Number of studies

The search strategy generated 796 articles in MEDLINE, 300 in EMBASE, 20 in IPA and 195 in CINAHL. Further refinement using the exclusion and inclusion criteria and duplicate exclusion resulted in 47 studies identified and reviewed (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of educational intervention studies for prescribing

| Authors | Setting | Study design | Number of participants | Intervention | Prescribing outcome measures | Results | Potential for bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akici et al25 | Turkey | Randomised controlled trial | 12 GPs in intervention group; 13 GPs in control group | Short rational pharmacotherapy course based on the ‘problem-based Groningen/WHO model’ | Written examination with open and structured questions based on hypertensive cases as well as a question on osteoarthritis (unexposed indication) | Significant improvement in the mean test scores post-training of the intervention group (p<0.05) for both questions, showing a transfer effect. The improvement was maintained for at least 4 months after training | None declared |

| Butler et al43 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 34 medical practices with 139 GPs were in the intervention group; 34 medical practices with 124 GPs in the control group | The intervention contained 7 parts. Six of these were online and included a reflection on their own practice, evidence and guidelines, novel communication skills and sharing experiences. Last, a face-to-face presentation of resistance trends throughout Wales and actual practices | Total numbers of oral antibiotic items dispensed for all causes per 1000 practice patients adjusted for the previous year's dispensing | A significant reduction of total oral antibiotic dispensing for the intervention group was observed compared with the control group (664 vs 681.1, p=0.02) | None declared |

| Celebi et al26 | Germany | Randomised controlled trial | 36 medical students in early intervention group; 38 medical students in late intervention group | A 1-week prescribing training module which comprised a seminar on common prescription errors, a prescribing exercise with a standardised paper case patient, drafting of inoperative prescription charts for real patients and discussions with a lecturer | Students were asked to make prescriptions for two virtual cases on a standard patient chart. These prescription charts were subsequently analysed by two independent raters using a checklist for common prescription errors | Prior to training, students committed a mean of 69±12% of the potential prescription errors. This decreased to 29±15% after prescribing training (p<0.001) | None declared |

| De Vries et al27 | Eight countries in Asia and Europe | Randomised controlled trial | 194 medical students in personal formulary (PF) group; 198 in existing formulary (EF) group; 191 in control group | The PF and EF groups were given teaching sessions based on the WHO Guide to Good Prescribing model (PF group=whole manual; EF group=manual minus p-drugs), with and without use of PF | Written examination using 16 patient cases based on four topics: hypertension, osteoarthritis, acute bronchitis, gastroenteritis | A significant increase in mean scores of the intervention group compared with the control group (p<0.05). The increase in the PF group was significantly higher than in the EF group. However, this effect was only visible in the universities in Yemen, the Russian Federation, and Indonesia. No significant differences between PF and EF scores were found in the universities in the Netherlands, Slovakia, Spain, India or South Africa | Funded by the VU University Medical Center and by the Department of Essential Drugs and Medicines Policy of the WHO |

| Degnan et al28 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 9 medical students in intervention group; 35 in the control group | An online teaching module consisting of an interactive tutorial of 12 multiple-choice questions and three case studies covering pharmacokinetics, adverse drug reactions and drug doses calculations | OSCE station requiring administration of lidocaine and adrenaline for a patient with laceration and anaphylaxis | The teaching module significantly improved the students’ ability to calculate the correct volume of lidocaine (p=0.005) and adrenaline (0=0.0002) | Funded by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Esmaily et al29 | Iran | Randomised controlled trial | 58 GPs in intervention group; 54 GPs in control group | Education with an outcome-based approach utilising active-learning principles | Multiple choice and short answer questions, with two case scenarios and three ‘irrational’ prescriptions | There was an overall improvement of 26 percentage units in the prescribing knowledge and skills of GPs in the intervention group. No such improvements were seen in the control group | Additional funding from the National Public Health Management Centre in Tabriz and the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran |

| Fender et al30 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 54 GPs in intervention group; 46 GPs in control group | An educational package based on principles of ‘academic detailing’ | The appropriate prescribing of tranexamic acid, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and norethisterone | A proportionately higher level of appropriate prescribing was found in the intervention group. An increase of 63% in the prescription of tranexamic acid, the most effective first line treatment for menorrhagia, was observed in the intervention group | None declared |

| Gordon et al42 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 76 junior doctors in intervention group; 86 in control group | A 1–2 h e-learning course on paediatric prescribing | Total correct responses on each prescribing assessment. Drug selection, prescribing calculations for children, discussing therapies and sources of errors were assessed | A significant increase in correct responses by the intervention group compared with the control group at both 4 and 12 weeks after the intervention. At 4 weeks: 79% vs 63% (p<0.0001) At 12 weeks: 79% vs 69% (p<0.0001) |

None declared |

| Hassan et al31 | Yemen | Randomised controlled trial | 56 medical students in intervention group; 44 students in control group | A prescribing course based on WHO's Guide to Good Prescribing, the Yemen Essential Drug List and Yemen Standard Treatment Guidelines | Written examination based on eight patient problems where a complete treatment plan form must be completed | Students from the study group performed significantly better than those from control in all problems presented and also when compared with the results of the pretest (p<0.05) | None declared |

| Hux et al32 | Canada | Randomised controlled trial | 135 GPs in intervention group; 116 GPs in control group | Mailed packages of prescribing feedback and guidelines-based educational materials | Median antibiotic cost and proportion of episodes of care in which a prespecified first-line antibiotic was used first | The median prescription cost remained constant in the feedback group but rose in the control group (p<0.002). First-line drug use increased in the feedback group but decreased in the control group (p<0.01) | Author receives salary support from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Ontario |

| Kahan et al33 | Israel | Randomised controlled trial | 32 physicians exposed to both interventions; 130 physicians who only received personalised letter; 29 physicians who only attended the lecture; 107 in the control group | Interventions were in the form of a lecture at a conference and a letter with personalised feedback to improve physicians’ rates of prescribing in the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in adult women | Outcome was the rate of adherence to the guidelines for appropriate treatment using nitrofurantoin or second-line therapy of ofloxacin for 3 days | The letter intervention significantly influenced physicians’ prescribing patterns. The lecture intervention was only effective in the short run, indicating that the effect of this technique does not last unless reinforced | Partially funded through a research grant from The Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and through an educational grant from Schering Plough Israel |

| Midlöv et al34 | Sweden | Randomised controlled trial | 23 GPs in the intervention group; 31 GPs in the control group | Educational outreach visits | Number of prescriptions of benzodiazepines (BDP) and antipsychotics to the elderly | One year after the educational outreach visits there was a significant decrease in prescribing of medium-acting and long-acting BDP and total BDP in the active group compared with the control group (p<0.05). For antipsychotics there were no significant differences between active and control group | Funded by the Department of Primary Care Research and Development in the county of Skåne, Apoteket AB and the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University |

| Nsimba35 | Tanzania | Randomised controlled trial | 20 pharmacists in intervention facilities; 20 in control facilities | Posters, individual information and one-to-one training sessions | Simulated clients assessed the drug seller/pharmacist's knowledge and prescribing choices. A short examination was also conducted to assess participants’ knowledge of appropriate treatments for common childhood conditions | 85% of simulated clients who went to the intervention facilities were sold the first line drug sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (SP) compared with 55% at control facilities (p<0.01). The intervention group also performed significantly better on the knowledge examination (p<0.01) | Funded by COSTECH-Tanzania |

| Ochoa et al36 | Cuba | Randomised controlled trial | 4 groups of 10 physicians (A, B, C, D) with A receiving community education programme and refresher training, B receiving refresher training, C receiving community education, D was the control group | Refresher training based on teaching sessions and periodic advisory visits. Community education involved group discussions and distribution of educational materials | Rate of overprescription of antibiotics for mild-acute respiratory infection (ARI) cases | Following the interventions, antibiotic overprescription rates declined by 26% and 63% in groups A and B, while increasing by 2% and 48% in groups C and D | None declared |

| Odusanya and Oyediran37 | Lagos state, Nigeria | Randomised controlled trial | Number of participants not specified. Primary healthcare workers (no doctors) in Mushin were in the intervention group; health workers in Ikeja were in the control group | 4-week training programme on rational drug use | Prescriptions were evaluated according to compliance to ‘standing orders’, which are a set of treatment modules. Drug use indicators were also compared | At the 2-week evaluation, the intervention group achieved a significant reduction in the average number of medicines prescribed compared with the control group. There was also a significant increase in the percentage of patients rationally managed from 18% to 30% (p=0.0005) in the intervention group. Improvements were not sustained at the 3-month evaluation | None declared |

| Rothmann et al38 | South Africa | Randomised controlled trial | 35 primary healthcare nurses in the intervention group; 31 in the control group | A competency-based primary care drug therapy training programme in the treatment of acute minor ailments | Written examination with 8 case studies including scenarios on acute gout, congestive heart failure, acute tonsillitis and infectious arthritis | Post-test results of the intervention group indicated significant improvement towards correct diagnosis and management of the conditions (p<0.05) | Funded by Boehringer Ingelheim (Pty) Ltd (Self-Medication Division) |

| Sandilands et al18 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 50 medical students in the intervention group; 28 students in control group | Focused doctor-led and pharmacist-led practical prescribing teaching | Written prescribing examination consisting of six scenario-based questions | Teaching improved the assessment score of the intervention group: mean assessment 2 vs 1, 70% vs 62%, p=0.007; allergy documentation: 98% vs 74%, p=0.0001 and confidence. However, 30% of prescriptions continued to include prescribing errors | None declared |

| Scobie et al39 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 16 medical students in intervention group; 16 students in control group | Practical structured teaching sessions led by a pharmacist | Nine station OSCE examination covering topics such as anticoagulation, intravenous administration, discharge prescription and medication history | The intervention group achieved higher scores in 8 OSCE stations. Four of these were statistically significant (p<=0.005) | None declared |

| Smeele et al40 | The Netherlands | Randomised controlled trial | 17 GPs in the intervention group; 17 GPs in control group | Four sessions (lasting 2 h each) of interactive group education and peer-review programme aimed at implementing national guidelines | Data on prescription of inhaled and anti-inflammatory medications were collected through self-recording by GPs and recording of repeat prescriptions for patients | No significant difference was found in the pharmacological treatment between intervention and control groups (p>0.05) | None declared |

| Webbe et al41 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | 13 preregistration house officers | A clinical teaching pharmacist programme to improve prescribing skills | Number of prescribing errors | A 37.5% reduction (p=0.14) in prescribing errors after pharmacist intervention | None declared |

| Akici et al47 | Turkey | Non-randomised comparative control | 50 medical students (interns) in intervention group; 54 interns in control group; 53 GPs | Problem-based rational pharmacotherapy education via the WHO/Groningen model | A written examination with open and structured questions based on case scenarios of tonsillitis and mild-to-moderate essential hypertension patients | Mean scores of the interns in the intervention group were higher than GPs, which were in turn higher than those of interns in the control group for all cases | Funded by a grant from Marmara University Scientific Research Projects Commission |

| Akram et al56 | Malaysia | Non-randomised comparative control | 18 final year dental students in the intervention group; 19 in the control group | Didactic lecture on how to write a complete prescription | Three case studies including irreversible pulpitis associated with a child, a pregnant woman and periapical pulpitis for an adult man. Assessed according to WHO's Guide to good prescribing | Significant improvement in the intervention group occurred compared with the control group in the following areas; date of issue, Rx symbol present, medicine legible, direction to use medicines, refill instructions, prescriber's signature, prescriber's date and prescriber's registration | Funded by the faculty of medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

| Al Khaja et al57 | Bahrain | Non-randomised comparative control | 460 medical students over different stages of the degree were in the intervention group; 450 in the control group | A 2 h interactive session on prescription writing skills is presented followed by 5–6 case scenarios given as homework. Formative feedback on these cases was given to the students | A written examination. Physician-related components of the prescription assessed legality of prescription writing while drug-related components relate to the rational and appropriate use of medicines | Significantly higher scores were achieved by those that attended the interactive sessions compared with those that did not. 73.5% vs 59.5% (p<0.0001) | No funding received |

| Al Khaja et al48 | Bahrain | Non-randomised comparative cohort | 539 medical students | Problem-based learning curriculum incorporating a prescribing programme | A written examination. Physician-related components of the prescription assessed legality of prescription writing while drug-related components relate to the rational and appropriate use of medicines | Rate of physician-related components by students (years 2–4) was 96.1 (CI 94.1 to 97.5). However, the rate of various drug-related components was 50.2 (CI 46.0 to 54.4). No significant difference in overall performance of years 4 and 2 students (p=0.237). However appropriateness of drug-related components was significantly higher in year 4 than 2 (p<0.05) | None declared |

| Celebi et al49 | Germany | Non-randomised comparative control | 18 medical students who had never completed an internal-medicine clerkship; 38 students who had completed 1–4 weeks of clerkship; 18 students who had completed>5 weeks of clerkship | Internal medicine clerkship based on one general learning objective of ‘students are to be familiarised with caring for patients in an outpatient and inpatient setting’ | A written test comprising of the completion of prescription charts for two standardised patient paper cases. These were marked using a checklist for common prescription errors | Students committed 69%±12% of all possible prescription mistakes. There was no significant difference between the group without clerkships in internal medicine (G1) (71±9%), the group with 1–4 weeks (G2) (67±15%), and the group with more than 5 weeks of clerkships (G3) (71±10%), p=.76 | None declared |

| Coombes et al50 | Australia | Non-randomised comparative control | 99 medical students in intervention group; 134 in control group | Eight interactive problem-based tutorials covering topics such as antibiotics, anticoagulants, intravenous fluids, analgesics, oral hypoglycaemics and insulin | A written examination consisting of short answer questions on ADR identification, anticoagulants and analgesics | A significantly higher score was found in intervention students compared with controls; mean score in intervention group 29.46; control group 26.35 (p<0.05) | None declared |

| Franson et al51 | The Netherlands | Non-randomised comparative cohort | 181 medical students in baseline 2003 cohort, 285 students in 2004, 275 students in 2005, 264 students in 2006 | Students were taught to use a structured format called the Individualised Therapy Evaluation and Plan (ITEP) to communicate a therapeutic plan including the writing of a prescription | Written examination involving two different therapeutic cases; a simple paediatric case and a complex geriatric case | Students’ scores improved significantly in the 3 years after the introduction of the ITEP in the curriculum. The average score of the 2006 cohort was 6.76 compared with 3.83 for the 2003 group (p<0.0001) | None declared |

| Kozer et al52 | Canada | Non-randomised comparative control | 13 trainees in intervention; 9 trainees in control | 30 min tutorial focusing on appropriate methods for prescribing medications followed by a written test | Main outcome measure was the number of prescribing errors on medication charts completed after the tutorial | No significant difference in errors was found between the intervention group (12.4%) and the control group (12.7%) | Funded by the Trainee's Start-up Fund, The Research Institution, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto Canada |

| McCall et al44 | Australia | Non-randomised comparative control | 14 GPs in intervention group; 14 in control group | Completion of a Graduate Certificate in General Practice Psychiatry conducted primarily via distance education programme | A clinical audit assessed GPs’ recognition, drug management, non-drug management of patients with depression and anxiety | No effect on the intervention GPs prescribing habits (p>0.05) | None declared |

| Pandejpong et al53 | Thailand | Non-randomised comparative control | 38 continuity of care (CCC) participants; 52 non-CCC participants | CCC curriculum | Medical chart audits were performed and scored with a 12-task checklist of cardiovascular risk management including appropriate prescribing | There was a significant increase in ability to properly adjust antihypertensive medication and in the prescribing of aspirin as primary prevention for cardiovascular disease in the CCC group (p<0.05) | Funded by a Faculty of Medicines Siriraj Hospital Medical Education Research Grant, Mahidol University |

| Richir et al54 | The Netherlands | Non-randomised comparative control | 197 medical students in the intervention group; 33 students in control | A context-learning pharmacotherapy programme with role-play sessions and OSCE | A written examination involving the formulation of a treatment plan for two patients using the WHO six-step guide of rational prescribing | The mean score on the six steps of the WHO six-step plan for prescribing increased significantly for students who have received the pharmacotherapy study (p<0.001) | None declared |

| Shaw et al45 | Australia | Non-randomised comparative control | The number of junior doctors in intervention and control hospitals was not specified | Academic detailing including the provision of a bookmark containing the requirements for addictive medicines | Prescription error rates of addictive medicines were assessed. Errors were defined according to legal requirements for prescription of addictive medicines | At the intervention hospital, there was a significant decrease in error rate (from 41% to 24%, p<0.0001). The control hospital did not show a significant change in error rate over the same study period (p=0.66) | Partially funded by the Postgraduate Medical Council of NSW |

| Tamblyn et al55 | Canada | Non-randomised comparative cohort | 751 doctors from four graduation cohorts; 600 from before the intervention and 151 after the intervention | A community-oriented problem-based learning curriculum | Annual performance in diagnosis (difference in prescribing rates for specific diseases and relief of symptoms), and management (prescribing rate for contraindicated medicines) assessed using provincial health databases for the first 4–7 years of practice | After the intervention, graduates showed a significant fourfold increase in disease specific prescribing rates compared with prescribing for symptom relief. No difference in rate of prescribing for contraindicated medicines was observed | Funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Fonds de Recherche en Sante du Quebec |

| Volovitz et al46 | Israel | Non-randomised comparative control | 83 physicians attended the education programme. Four groups of patients were included. The study group had patients whose physicians attended the education programme and completed two follow-up physician visits. Three control groups of patients were also included | Asthma education programme involving lectures on pathophysiology, asthma management and prevention. Physicians were also asked to invite patients for three visits to reinforce the principles highlighted in the education programme | Changes in asthma medicine use were analysed before and after the intervention. Data were derived from the central database of Maccabi, Israel | In all four patient groups, a smaller proportion of reliever medicines (SABA) and a greater proportion of controller medicines (ICS and LABA) were used in the follow-up period compared with before the intervention. Patients in the study group were twice more likely to decrease their use of SABA than patients from the control group (p=0.042) | None declared |

| Wallace et al58 | UK | Non-randomised comparative control | 20 final year medical students in the intervention group; 11 in the control group | 8 tutorials on prescribing in acute clinical scenarios using peer assisted learning | Accurate completion of a prescription chart | The intervention group significantly improved after the intervention; median score was 47 before; 66 after (p<0.01). No significant change occurred in the control group (p=0.17) |

None declared |

| Aghamirsalim et al69 | Iran | Before and after study | 72 orthopaedic surgeons | Formal 2 h lectures once a week for 4 weeks and a 30 min refresher course was offered at the 4th month. Also, simplified osteoporosis guidelines were distributed | Proportion of patients with fragility factures who received appropriate treatment for osteoporosis | Significantly more patients were appropriately prescribed calcium and vitamin D supplements on discharge. 10% vs 91% (p<0.05). Significantly more patients were appropriately prescribed a bisphosphonate on discharge. 0.1% vs 73% (p<0.05) | None declared |

| Bojalil et al59 | Tlaxcala, Mexico | Before and after | 72 private GPs; 44 public GPs | A training course based on in-service practice. Other materials included the official training manuals for the control of diarrhoea and ARI, training videos and wall charts | Aspects of diarrhoea and ARI treatment which were evaluated and scored using a checklist | Private practitioners showed significant improvements in prescribing practices for children with diarrhoea. For ARI management, decisions on antimicrobial therapy and symptomatic drug use improved for both groups but only reached statistical significance for public physicians | Funded by the Mexican Social Security Institute |

| Chopra et al60 | Cape Town, South Africa | Before and after | 21 nurse prescribers | WHO and UNICEF's Integrated Management of Childhood Illness implementation. Training used the WHO/UNICEF teaching and assessment modules | A structured observation checklist of the case management of sick children including rational prescribing | There were significant improvements in the appropriate prescribing of antibiotics, with a significant reduction of inappropriate antibiotic use (62% vs 84%). However, there was no change in the treatment of anaemia or the prescribing of vitamin A to sick children |

None declared |

| Davey et al 61 | UK | Before and after | The number of junior doctors included in the study was not specified | A paediatric junior doctor prescribing tutorial conducted by a pharmacist and a bedside prescribing guideline to encompass the most frequently prescribed medications utilised on the children's unit | Prescribing errors and preventable adverse drug events | The introduction of the prescribing tutorial decreased prescribing errors by 46% (p=0.023). The introduction of a bedside prescribing guideline did not decrease prescribing errors | Author's research position was funded by Airedale NHS Trust |

| Elkharrat et al62 | France | Before and after | 27 doctors | Doctors were informed of the Drug Regulatory Agency prescribing guidelines of NSAIDs. Group sessions were held, posters were displayed and pocket sized, 10-page manuals were distributed | The rate of NSAID prescribing errors was analysed | Prescribing errors declined from 20% to 14% and when prescriptions were stratified by cause, the quality of prescribing increased significantly | None declared |

| Guney et al64 | Turkey | Before and after study | 101 medical students | Rational pharmacotherapy training based on the Groningen/WHO model | Prescription audit and OSCE examination based on a simulated patient case with uncomplicated essential hypertension | A significant improvement in prescription audit scores was observed after the training (p: 0.022) | None declared |

| Gall et al63 | UK | Before and after study | 212 GPs; 139 community nurses | Training on the use of guidelines on prescribing supplements | Changes in prescribing practice of supplements | Education significantly reduced total prescribing by 15% and reduced the levels of inappropriate prescribing from 77% to 59% due to an improvement in monitoring of patients prescribed supplements | Funded by South Thames Health Authorities Clinical Audit Programme |

| Leonard et al65 | USA | Before and after study | The number of clinical staff (physicians, nurses, pharmacists) included in the study was not specified | Educational patient safety initiatives using multiple interrelated educational and behavioural modification strategies | Assessment of medication orders which were then used to calculate the absolute risk reduction from prescribing errors | The absolute risk reduction achieved after the interventions was 38/100 orders written (t=25.735; p=0.001). This yielded an overall relative risk reduction from prescribing errors of 49% (p<0.001) |

Funded by the New York State Department of Health 2003 Patient Safety Award and by a donation from Lexi-Comp of Pediatric Lexi-Drugs limited licenses |

| Minas et al70 | Australia | Before and after study | GPs and healthcare prescribers in Emergency Departments and Sexual Health Clinics. Number included not specified | Treatment guidelines were distributed and informed through professional development sessions, letters and newsletters | Proportion of patients receiving non-occupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) according to the relevant treatment guidelines | Significantly more patients that received nPEP met the eligibility criteria as stated in the relevant treatment guidelines after the educational intervention. 61.2% vs 90% (p<0.001) | None declared |

| Otero66 | Argentina | Before and after study | Number of participants not specified. Prescriptions for 95 patients were analysed in 2002 and for 92 patients in 2004 | Educational programme developed by the Patient Safety Committee of the Department of Pediatrics including the implementation of the ‘10 steps to reduce medication errors’ checklist | Prevalence of medication errors detected in written prescription orders during June 2002 (before intervention) and May 2004 (after intervention) | Prevalence of prescription errors was significantly lower in 2004 compared with 2002; 11.4% vs 7.3% (p<0.05) | None declared |

| Taylor et al67 | UK | Before and after study | 242 junior doctors | 1 h interactive, case-based educational programme regarding inpatient diabetes care | Number of insulin prescribing errors on medication charts observed after the tutorial | Insulin prescription errors were significantly lower after the intervention; 15.4% vs 7.8% (p<0.05) | None declared |

| Zgheib et al68 | Lebanon | Before and after study | 127 final year medical students divided into 18 groups of 6–7 students | 5 team-based learning (TBL) based on WHO's Guide to Good Prescribing. A lecture on the role of the pharmacist, Pharmacy and Therapeutics committees, formularies and hospital policies were also presented | Group formulary and prescription writing exercises occurred after each TBL session. Rationale for the selection of a drug and the format of the prescription was included in these assessments | Significant improvement in mean group scores for both formulary and prescription-writing exercises occurred over the 5 TBL sessions (p=0.002) | None declared |

GP, general practitioner.

Study designs

Of the 47 reviewed studies, there were 20 randomised controlled trials (RCTs),18 25–43 15 non-randomised comparative trials44–58 and 12 before-after studies.59–68

Setting and participant characterisation

Ten educational interventions were targeted at general practitioners (GPs),25 29 30 32–34 40 44 46 63 10 were conducted in hospitals,41 45 52 59 61 62 65–67 69 six were implemented at primary healthcare clinics/facilities,36–38 43 60 70 20 interventions were incorporated within the curriculum at universities18 26–28 31 39 42 47–51 53–58 64 68 and one intervention was carried out in pharmacies.35 These studies were conducted in numerous countries around the world (table 1).

Types of educational interventions and prescribing outcomes

A wide variety of educational methods and outcome measures were used. Interventions were summarised into two categories using Miller's competency model:

Prescribing competence (‘knows how’)—assessing prescriptions written for theoretical cases;

Prescribing performance (‘shows how’)—assessing prescriptions written for real patients.

Prescribing competence

Twenty studies included interventions targeting particular tasks involved in prescribing, from taking accurate medication history, in choosing a rational treatment and writing the prescription.18 25–29 31 39 42 47–51 54 56–58 64 68 Eight of these studies used a method of rational pharmacotherapy education based on the WHO Guide to Good Prescribing.25 27 31 47 54 56 64 68 De Vries et al27 conducted a multicentre RCT with 583 medical students from eight countries. The trial reported a significant increase in mean scores of the intervention group following the WHO Guide to Good Prescribing intervention.

Other studies found evidence of a retention effect, where improvement in rational prescribing was maintained several months after the intervention25 42 and a transfer effect, where students were able to apply acquired rational prescribing skills in new situations.25 54 The main limitation of the trials was that assessments were based primarily on written scenarios with a limited number of disease topics.

Four studies examined the effect of structured prescribing tutorials and programmes on prescribing skills of medical students and GPs.29 39 42 50 Three, specifically covered high-risk medicines and reported significant improvements in prescribing skills.29 39 50 Prescribing outcomes were assessed using written case scenarios29 50 and a nine-station OSCE.39

Five studies assessed prescription writing skills of medical students following a prescribing programme at university.48 51 57 58 68 Al Khaja et al48 evaluated a prescribing programme incorporated into a problem-based learning (PBL) curriculum. Students acquired limited prescribing competency during the PBL programme. Only 50.2% correctly selected appropriate medicine(s), strength and dosage-form in the written examination.48 Al Khaja et al57 later used a 2 h interactive session on prescription writing skills with formative feedback. This programme increased appropriate medicine(s) selection to 83.9%, appropriate strength to 68% and appropriate dosage form to 59.6%.57 The other three studies used peer-assisted learning,58 team-based learning (TBL) based on WHO's Guide to Good Prescribing68 and Individualised Therapy Evaluation and Plan (ITEP) in the curriculum.51 The TBL and ITEP format allowed students to provide a rationale-based treatment plan for an individual patient. Both TBL and ITEP improved students’ ability to solve therapeutic problems and select appropriate medications.51 68 However, all of these studies were non-randomised making it difficult to attribute their findings to the impact of interventions alone.

Three studies measured the incidence of prescribing errors in written scenario-based examinations.18 26 49 Specific prescribing tutorials/teaching modules significantly reduced prescription errors.18 26 However obligatory medical clerkships, where students are assumed to acquire prescribing skills by spending up to 16 weeks with a GP or in a hospital setting, did not have a significant effect on the rate of prescription errors.49

One study examining an online interactive teaching module found a significant improvement in students’ ability to calculate correct volumes of lignocaine and adrenaline in an OSCE setting.28

Prescribing performance

Twenty-seven studies used educational interventions which aimed to improve management of particular conditions and increase the appropriateness of prescribing.30 32–38 40 41 43–46 52 53 55 59–63 65–67 69 70

In 11 of these studies, interventions were implemented to specifically promote prescribing first-line therapy or reduce inappropriate prescribing.30 32–36 43 62 63 69 70 Academic detailing approaches30 and educational outreach visits,34–36 63 were found to show positive results in improving prescribing adherence to guidelines. Mailed personalised prescribing feedback32 33 was also found to be effective. An intervention in the form of a lecture was found to be ineffective unless reinforced with another intervention, for example, individual feedback.33 An in-house training programme was found to reduce the inappropriate prescribing of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but results were not statistically significant.62

Nine studies used educational interventions to improve overall treatment practices of various conditions, with appropriate and rational pharmacological therapy assessed.37 38 40 44 46 53 55 59 60 The methods which reported improvements included educational outreach visits,37 38 in-service training59 and a multipronged approach involving training sessions and some reorganisation of management systems.60 Two studies assessed the effectiveness of curriculum changes at university on medical graduates’ patient-care performance.53 55 Both a PBL curriculum55 and a continuity of care clinic curriculum53 increased prescribing performance indicators. However, outcome measures differed, with one study assessing prescribing rates in ambulatory patients aged >65 years55 and the other focusing specifically on cardiovascular risk management.53

Mixed results were found in two studies which evaluated asthma management following an educational intervention.40 46 An intensive small-group education session and peer-review programme did not show a significant influence on adherence to guidelines for general pharmacological treatment and management of exacerbations.40 Another study found a positive change in medication prescribing following an asthma education programme; however, the intervention and control groups showed this change in practice.46

McCall et al44 examined the impact of a distance-learning graduate course in general practice psychiatry on managing mental illness. Although the intervention had a positive impact on GP's knowledge, there was no significant effect on overall prescribing habits.

Seven studies evaluated the impact of educational interventions on the rate of prescribing errors using an audit of medication charts before and after the intervention.41 45 52 61 65–67 Multidisciplinary interventions using interrelated educational and behavioural modification strategies significantly reduced prescribing errors.65 66 Academic detailing reduced the number of incorrect prescriptions written for addictive medicines,45 however prescription errors were defined only on the basis of local state laws in Australia and no assessment of the appropriateness of the choice of medicines was made. Webbe et al41 reported a reduction in prescribing errors following pharmacist accompaniment on prescribing rounds and a clinical teaching pharmacist programme. However, the small sample meant that statistical significance was not reached. Two studies assessed the effect of a prescribing tutorial on the incidence of paediatric prescribing errors.52 61 Both tutorials focused on prescribing in the paediatric population; however, the studies reported mixed results. Kozer et al52 found no difference in prescribing errors whereas Davey et al61 reported significant differences.

Discussion

Although a considerable amount of research has been conducted in improving prescribing competency through educational interventions, the range of heterogeneous study designs and outcome measures limits the validity and the ability to generalise their conclusions.

According to Miller's framework of competency assessment, tests of knowledge alone are insufficient to properly assess educational interventions. Hence, the assessment of prescribing skills included in these studies mainly focused on Miller's pyramid base ‘knows how’ and ‘shows how’. The translation of knowledge and skills into a rational diagnostic or management plan is defined as competency (knowing how), which was measured using written examinations, patient management or OSCEs. This in turn predicts performance (showing how) and action (does) which was evaluated in daily life circumstances through audits to detect prescription errors or direct observations of prescribers’ performance using standardised checklists. However, prescribing performance is difficult to measure as it can be influenced by many factors such as physicians’ clinical experience, sociocultural factors, histopathology of disease, pharmaceutical industry representatives and the ever-increasing pressure from patients.25

Although studies differed considerably in their methods and assessment procedures, a number of key findings were highlighted. First, specific prescribing teaching can lead to improvements in prescribing competency. This was reported in studies that used tutorials and educational programmes to guide participants in the process of rational prescribing.25 27 29 31 39 47 48 50 51 54 64 Of these studies, only the WHO Guide to Good Prescribing has been evaluated for both medical students and GPs across a range of countries.25 27 31 47 54 64 68 The WHO model provides a six-step guide to choose, prescribe and monitor a suitable medicine for an individual patient and presents a good foundation for the development of therapeutic reasoning in a prescribing curriculum. This model is in line with the prescribing competency framework developed by the National Prescribing Centre16 and NPS MedicineWise.17 It also provides important guidance in the development of educational interventions for medical and non-medical prescribers. The WHO method also encourages prescribers to verify standard treatment for each patient (recognising issues such as aging or cognition impairment) and to alter treatment if necessary,25 which is an essential skill to acquire, particularly with the aging community.

Incorporating a prescribing component into a structured, problem-based curriculum also improved students’ ability to prescribe correctly.26 27 31 39 48 54 Although targeted prescribing-teaching is mainly implemented at the undergraduate level, studies have found that GPs and non-medical prescribers often do not apply rational prescribing principles in daily practice and would benefit from these interventions.25 35 37 38

Many studies attempted to influence prescribing behaviour through the promotion of rational medication use based on published practice guidelines. These guidelines have been promoted in face-to-face interactions and training through educational outreach visits, academic detailing and through institutional audits and feedback. All of these methods have positively affected health professionals’ behaviour.30 34 63 Although effective, these methods could be labour intensive and may be prohibitively expensive. Findings suggest that personalised feedback letters could be just as effective while blunting costs.32 33 There is scope to explore why these interventions work and determine which interventions are suitable for different types of prescribers and settings.

Prescribing practices can also be improved through enhanced communication between doctors, pharmacists, nurses, other health professionals as well as patients and carers. Several studies highlight the interactive role of medical, pharmacy and nursing staff in ensuring safe and effective use of medicines.18 35 39 41 50 59 61 This is not surprising, as many prescribing errors cannot be attributed to knowledge deficits alone.18 Hence improving prescribing practices may require interventions aimed at multiple operant factors, such as developing a safety-oriented attitude through improving environment conditions, direct staff supervision and adopting a zero-tolerance policy for incomplete or incorrect prescriptions.66 Indeed positive results were reported following multifaceted interventions where education was incorporated into a system-based approach to influence prescribing behaviour.65 66

Finally, this review has highlighted a lack of educational interventions targeted at non-medical prescribers. Four studies assessed the effectiveness of training programmes: two were for nurses,38 60 one for pharmacists35 and one for primary healthcare workers (community health officers, nurses and community health extension workers).37 All four studies had relatively small sample sizes and differed greatly in prescribing outcome measures. This suggests that further description and evaluation of educational methods is needed for non-medical prescribers.

Overall the conclusions that can be drawn are limited by the quality of the studies reviewed. The number of participants included ranged from 13 in an RCT41 to 751 in a cohort study.55 RCTs are considered the gold standard; however, the smaller studies may have been underpowered and hence could not produce statistically significant results. Nevertheless large-sample randomisation and effective blinding are often not appropriate or possible in prescribing intervention studies. The current literature also does not show if the improvements in prescribing persists after the intervention occurs as many studies only assess up to a few months after the intervention. Higher quality studies looking at long-term changes in prescribing habits is required to assess the effectiveness of educational interventions on prescribing.

Lastly, the different methods of assessments were often used with no discussion about their validity and reliability, and marking schemes were inconsistent across the different studies. For example, the definitions of ‘prescription error’ differed slightly between studies and one study defined errors based on local state laws instead of on appropriateness of medication choices.45 The correlation between the duration of interventions and the impact on prescribing was also difficult to determine as the interventions ranged from a 30 min tutorial52 to a prescribing programme implemented for up to 3 years.51 53 55 This made assessing the quality of the studies difficult and no criteria appeared appropriate for this purpose.

As our search strategy excluded studies that were not in English, we were unable to report important educational strategies that may exist in this area. However, these interventions have already been shown to decrease costs and may subsequently improve prescribing appropriateness.22 23 Furthermore, the comprehensiveness of our review may have been limited by only including databases that we perceived would contain the bulk of the prescribing competency literature, using the key word ‘competency’ and following PRISMA guidelines24 which do not stipulate hand searches. Overall the studies retrieved provided a broad overview of a range of prescribing interventions and may be useful in identifying strategies that can be explored further in more robust, longer term trials in the future.

Conclusion

A wide range of educational interventions has been conducted to develop and maintain prescribing competency. However few studies have sought to evaluate the educational models used to develop non-medical prescribers’ prescribing competency and there is a need for further development in the assessment of teaching for non-medical prescribers as expansions of prescribing powers continue to be implemented. The development of competency frameworks for prescribing has highlighted the need to design interventions which target each prescribing competency domain. In particular, the WHO Guide to Good Prescribing is a promising model for the design of targeted prescribing programmes and has been shown to be effective in a wide variety of settings. The corresponding author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a worldwide license to the Publishers and its licensees in perpetuity, in all forms, formats and media (whether known now or created in the future) to: (1) publish, reproduce, distribute, display and store the Contribution; (2) translate the Contribution into other languages, create adaptations, reprints, include within collections and create summaries, extracts and/or, abstracts of the Contribution; (3) create any other derivative work(s) based on the Contribution; (4) to exploit all subsidiary rights in the Contribution; (5) the inclusion of electronic links from the Contribution to third party material where-ever it may be located and (6) license any third party to do any or all of the above.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GK, JP, BC and RM jointly developed the search strategy and reviewed the protocol. Data collection and extraction were carried out by GK and JP. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data, drafting the article and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hanes C, Bajorek B. Pharmacist prescribing: is Australia behind the times? Aust J Pharm 2004;85:680–1 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson JK. A prescription for better prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;61:487–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vries TP, Henning RH, Hogerzeil HV, et al. Guide to good prescribing. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryony Dean F, Vincent C, Schachter M, et al. The incidence of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: an overview of the research methods. Drug Saf 2005;28:891–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombes ID, Stowasser DA, Coombes JA, et al. Why do interns make prescribing errors? A qualitative study. Med J Aust 2008;188:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Likic R, Maxwell SRJ. Prevention of medication errors: teaching and training. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:656–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, et al. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: their incidence and clinical significance. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:340–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross S, Bond C, Rothnie H, et al. What is the scale of prescribing errors committed by junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:629–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garbutt JM, Highstein G, Jeffe DB, et al. Safe medication prescribing: training and experience of medical students and housestaff at a large teaching hospital. Acad Med 2005;80:594–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilmer SN, Seale JP, Le Couteur DG, et al. Do medical courses adequately prepare interns for safe and effective prescribing in New South Wales public hospitals? Intern Med J 2009;39:428–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper RJ, Anderson C, Avery T, et al. Nurse and pharmacist supplementary prescribing in the UK—a thematic review of the literature. Health Policy 2008;85:277–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Latter S, Maben J, Myall M, et al. Evaluating prescribing competencies and standards used in nurse independent prescribers’ prescribing consultations. J Res Nurs 2007;12:7–26 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65:S63–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma S, Paterson M, Medves J. Core competencies for health care professionals: what medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy share. J Allied Health 2006;35:109–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mucklow J, Bollington L, Maxwell S. Assessing prescribing competence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:632–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The National Prescribing Centre A single competency framework for all prescribers. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.NPS MedicineWise Competencies required to prescribe medicines: putting quality use of medicines into practice. Sydney: National Prescribing Service Limited, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandilands EA, Reid K, Shaw L, et al. Impact of a focussed teaching programme on practical prescribing skills among final year medical students. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;71:29–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostini R, Hegney D, Jackson C, et al. Systematic review of interventions to improve prescribing. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:502–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross S, Loke YK. Do educational interventions improve prescribing by medical students and junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:662–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan N, Mattick K. A systematic review of educational interventions to change behaviour of prescribers in hospital settings, with a particular emphasis on new prescribers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;75:359–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub3. Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD003543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6:CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:332–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akici A, Kalaca S, Ugurlu MU, et al. Impact of a short postgraduate course in rational pharmacotherapy for general practitioners. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2003;57:310–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celebi N, Weyrich P, Riessen R, et al. Problem-based training for medical students reduces common prescription errors: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ 2009;43:1010–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vries TPGM, Daniels JMA, Mulder CW, et al. Should medical students learn to develop a personal formulary? An international, multicentre, randomised controlled study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:641–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degnan BA, Murray LJ, Dunling CP, et al. The effect of additional teaching on medical students’ drug administration skills in a simulated emergency scenario. Anaesthesia 2006;61:1155–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esmaily HM, Savage C, Vahidi R, et al. Does an outcome-based approach to continuing medical education improve physicians’ competences in rational prescribing? Med Teach 2009;31: e500–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fender GR, Prentice A, Gorst T, et al. Randomised controlled trial of educational package on management of menorrhagia in primary care: the Anglia menorrhagia education study. BMJ 1999;318:1246–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan NA, Abdulla AA, Bakathir HA, et al. The impact of problem-based pharmacotherapy training on the competence of rational prescribing of Yemen undergraduate students. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000;55:873–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hux JE, Melady MP, DeBoer D. Confidential prescriber feedback and education to improve antibiotic use in primary care: a controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 1999;161:388–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahan NR, Kahan E, Waitman D-A, et al. The tools of an evidence-based culture: implementing clinical-practice guidelines in an Israeli HMO. Acad Med 2009;84:1217–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Midlöv P, Bondesson A, Eriksson T, et al. Effects of educational outreach visits on prescribing of benzodiazepines and antipsychotic drugs to elderly patients in primary health care in southern Sweden. Fam Pract 2006;23:60–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nsimba SED. Assessing the impact of educational intervention for improving management of malaria and other childhood illnesses in Kibaha District-Tanzania. East Afr J Public Health 2007;4:5–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochoa EG, Pérez LA, González JRB, et al. Prescription of antibiotics for mild acute respiratory infections in children. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 1996;30:106–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odusanya OO, Oyediran MA. The effect of an educational intervention on improving rational drug use. Niger Postgrad Med J 2004;11:126–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothmann JC, Gerber JJ, Venter OM, et al. Primary care drug therapy training: the solution for PHC nurses? Curationis 2000;23:43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scobie SD, Lawson M, Cavell G, et al. Meeting the challenge of prescribing and administering medicines safely: structured teaching and assessment for final year medical students. Med Educ 2003;37:434–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smeele IJ, Grol RP, van Schayck CP, et al. Can small group education and peer review improve care for patients with asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Qual Health Care 1999;8:92–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webbe D, Dhillon S, Roberts CM. Improving junior doctor prescribing—the positive impact of a pharmacist intervention. Pharm J 2007;278:136–8 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon M, Chandratilake M, Baker P. Improved junior paediatric prescribing skills after a short e-learning intervention: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:1191–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butler CC, Simpson SA, Dunstan F, et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted educational programme to reduce antibiotic dispensing in primary care: practice based randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344:d8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCall LM, Clarke DM, Rowley G. Does a continuing medical education course in mental health change general practitioner knowledge, attitude and practice and patient outcomes? Prim Care Ment Health 2004;2:13–22 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw J, Harris P, Keogh G, et al. Error reduction: academic detailing as a method to reduce incorrect prescriptions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2003;59:697–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volovitz B, Friedman N, Levin S, et al. Increasing asthma awareness among physicians: impact on patient management and satisfaction. J Asthma 2003;40:901–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akici A, Kalaça S, Gören MZ, et al. Comparison of rational pharmacotherapy decision-making competence of general practitioners with intern doctors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004;60:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al Khaja KAJ, Handu SS, James H, et al. Assessing prescription writing skills of pre-clerkship medical students in a problem-based learning curriculum. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;43:429–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Celebi N, Kirchhoff K, Lammerding-Koppel M, et al. Medical clerkships do not reduce common prescription errors among medical students. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2010;382:171–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coombes I, Mitchell C, Stowasser D. Safe medication practice tutorials: a practical approach to preparing prescribers. Clin Teach 2007;4:128–34 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franson KL, Dubois EA, de Kam ML, et al. Creating a culture of thoughtful prescribing. Med Teach 2009;31:415–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A, et al. The effect of a short tutorial on the incidence of prescribing errors in pediatric emergency care. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2006;13:e285–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pandejpong D, Nopmaneejumruslers C, Chouriyagune C. The effect of a continuity of care clinic curriculum on cardiovascular risk management skills of medical school graduates. J Med Assoc Thai 2009;92(Suppl 2):S6–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richir MC, Tichelaar J, Stanm F, et al. A context-learning pharmacotherapy program for preclinical medical students leads to more rational drug prescribing during their clinical clerkship in internal medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;84:513–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, et al. Effect of a community oriented problem based learning curriculum on quality of primary care delivered by graduates: historical cohort comparison study. BMJ 2005;331:1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akram A, Zamzam R, Mohamad NB, et al. An assessment of the prescribing skills of undergraduate dental students in malaysia. J Dent Educ 2012;76:1527–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al Khaja KAJ, James H, Sequeira RP. Effectiveness of an educational intervention on prescription writing skill of preclerkship medical students in a problem-based learning curriculum. J Clin Pharmacol 2013;53:483–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wallace F, Emerson SJ, Burton P, et al. Peer-assisted learning improves prescribing skills. Med Teach 2011;33:952–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bojalil R, Guiscafre H, Espinosa P, et al. A clinical training unit for diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections: an intervention for primary health care physicians in Mexico. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:936–45 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chopra M, Patel S, Cloete K, et al. Effect of an IMCI intervention on quality of care across four districts in Cape Town, South Africa. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:397–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davey AL, Britland A, Naylor RJ. Decreasing paediatric prescribing errors in a district general hospital. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:146–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elkharrat D, Chastang C, Lecorre A, et al. Prospective assessment of an intervention to rationalize prescribing of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Ther 1998;5:225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gall MJ, Harmer JE, Wanstall HJ. Prescribing of oral nutritional supplements in primary care: can guidelines supported by education improve prescribing practice? Clin Nutr 2001;20:511–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guney Z, Uluoglu C, Yucel B, et al. The impact of rational pharmacotherapy training reinforced via prescription audit on the prescribing skills of fifth-year medical students. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;47:671–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leonard MS, Cimino M, Shaha S, et al. Risk reduction for adverse drug events through sequential implementation of patient safety initiatives in a children's hospital. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1124–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Otero P, Leyton A, Mariani G, et al. Medication errors in pediatric inpatients: prevalence and results of a prevention program. Pediatrics 2008;122:e737–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor CG, Morris C, Rayman G. An interactive 1-h educational programme for junior doctors, increases their confidence and improves inpatient diabetes care. Diabet Med 2012;29:1574–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zgheib NK, Simaan JA, Sabra R. Using team-based learning to teach clinical pharmacology in medical school: student satisfaction and improved performance. J Clin Pharmacol 2011;51: 1101–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aghamirsalim M, Mehrpour SR, Kamrani RS, et al. Effectiveness of educational intervention on undermanagement of osteoporosis in fragility fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132:1461–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Minas B, Laing S, Jordan H, et al. Improved awareness and appropriate use of non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) for HIV prevention following a multi-modal communication strategy. BMC Public Health 2012;12:906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.