Abstract

Objective

To test whether the relatively unpredictable nature of labour onset can be described by the Poisson distribution.

Design

A descriptive retrospective study.

Setting

From the Danish Birth Registry, we identified births from all seven obstetric clinics in the capital region of Denmark (n=211 290) between 2000 and the end of 2009. On each date, the number of births at each department was registered. Births are categorised based on whether an elective caesarean section or induction of labour has been performed, and among the remaining ‘non-elective births’, acute caesareans were registered.

Methods

After the exclusion of elective caesarean sections and births after induction of labour, only ‘non-elective’ births (n=171 009) were included for the main statistical analysis. Simple descriptive plots and one-way analysis of variance were used to analyse the distribution of ‘non-elective’ births for each day of the week.

Main outcome measures

The daily number of ‘non-elective’ births.

Results

The number of ‘non-elective’ births varies considerably over the days of the week and over the year for each obstetric clinic regardless of clinic size. However, for each fixed day of the week, the variation over the year is well described by a Poisson distribution, allowing simple prediction of the variability. For births at each fixed day of the week, the Poisson distribution is indistinguishable from a normal distribution.

Conclusions

The number of ‘non-elective’ births for each day of the week is well described by a Poisson distribution. Consequently, the Poisson model is suitable for estimating the variation in the daily number of ‘non-elective’ births and could be used for planning of staffing in obstetric clinics. The model can be used in smaller as well as larger clinics.

Keywords: OBSTETRICS

Article summary.

Article focus

Does the Poisson distribution correspond precisely to actual random variation in the number of ‘non-elective’ births for each fixed day of the week?

Key messages

For each day of the week, the variation of ‘non-elective’ births over the year is well described by a Poisson distribution.

The Poisson distribution makes it easy to estimate the variation in the daily number of births and can be used for planning of staffing in obstetric clinics. Standard tables of the normal distribution may be used as exemplified.

The model is adequate for use in smaller as well as larger clinics and can be used in the management of staffing in obstetric clinics.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength is the large data set of non-selected births. The main limitation is that births are registered only by date, not by the time of birth.

Introduction

There is a structural reorganisation of hospitals going on in Denmark implying larger but fewer hospitals. This applies also to the departments of gynaecology and obstetrics as smaller departments are being merged, resulting in fewer larger departments.1–3 The main motivation for these changes has been that larger departments would enhance the capacity and quality of patient treatment and additionally reduce the costs for staff at shifts. In Denmark, the overall year-to-year variation in the number of births in each department is centrally determined as each department of gynaecology and obstetrics on an administrative level is intended to have a given number of births from a specified geographical region, and therefore the staffing required in each obstetric clinic in each department is determined from this figure. The largest part of staffing consists of a daily number of midwives working 8 h shifts during the day, evening and night, as well as a varying number of midwives on 24 h duty on call from home. Their actual working hours vary considerably. The number of doctors on shift is fixed for each obstetric clinic and depends on the size of the obstetric clinic, as does the number of doctors on call from home.

An interesting organisational feature in obstetrics is the inherent random variation in onset of spontaneous labour which makes it difficult to precisely plan the necessary number of staff at the obstetric clinics. The planning of staffing in the departments is, to our knowledge, not based on published methods. Statistics on the number of births on each day for each department every year is available online from Statistics Denmark.4 These numbers indicate considerable day-to-day variation and week-to-week variation. The observation of a weekly cycle is in accordance with reports from other countries such as England, Wales, Australia, the USA, Israel and Norway,5–13 and interestingly, it has also been shown that the variation depends on whether the Sabbath occurs on a Friday,14 a Saturday5 or a Sunday.6–13 However, these former studies included all births regardless of whether or not there had been an elective obstetric intervention, which raises the question whether the variation between the days of the week disappears when births resulting from an elective obstetric intervention as elective caesarean or induction of labour are excluded from the data set. There is a long tradition of describing the variation in the daily demand for hospital beds by the Poisson distribution,15–17 sometimes based on queuing theory and with varying efforts at empirical verification. In her well-known textbook, Kirkwood18 used an apparently hypothetical example of staffing planning in the face of merging two obstetrical departments to illustrate the Poisson distribution.

In this study, we examined from a broad Danish experience how well the Poisson distribution corresponds to actual random variation in the number of ‘non-elective’ births for each fixed day of the week. Since the variation in the ‘non-elective’ births is most obviously random, we exclude in the main analysis ‘elective’ births (resulting from induction of labour and elective caesarean sections). However, as a sensitivity analysis, we report results on the variation of all births and of acute caesarean sections.

Material and methods

Data

The number of births for each date in the period from 1 January 2000 until 31 December 2009 at all seven obstetric clinics in the capital region of Denmark was extracted from the Danish Birth Registry. The obstetric clinics were Rigshospitalet, Frederiksberg, Glostrup, Gentofte, Herlev, Hvidovre and Hillerød, which cover over 99% of all births in the region, as a dwindling number of births takes place at home in Denmark. The data included information on the type of birth: elective caesarean sections, births after elective induction of labour, acute caesarean sections and births after spontaneous onset of labour. The labelling of the type of birth has been performed by using information from the National Birth registry on operation codes for elective caesarean sections (KMCA10B and D) and obstetric codes for induction of labour (KMAC00 amniotomy prior to birth, KMAC96A mechanical catheter induction, BKHD2 unspecific medical induction, BKHD20 induction with prostaglandin and BKHD21 induction with oxytocin). The coding of birth information is based on information from midwives and is generally considered very valid.

Statistical methods

The main concept of these analyses builds on the empirical fact that even for ‘non-elective’ births there is a non-ignorable variation across the 7 days of the week; however, for each fixed day of the week, the variation across the 52 (53) weeks in a given year may be interpreted as random. We exploit the well-known fact that Poisson distributions are well approximated by normal distributions with the same mean and variance, clearly distinguishable by the Poisson distribution property that the mean equals the variance. In this way, the key issue—whether the Poisson distribution is an adequate description—is captured by a one-way analysis of variance comparing the 7 days of the week for each of the 10 years and each of the seven clinics. The results are illustrated by descriptive graphs and worked examples of possible use in staffing planning. Additional sensitivity analyses are performed including all births and acute caesareans.

Details of ethics approval

The data used are available online in an anonymous form.

Results

There were 211 290 births distributed on seven departments in the capital region of Denmark from 1 January 2000 until 31 December 2009. In order to exclude potential elective births, births were subdivided into induced or spontaneous labour and elective and acute caesareans (table 1). Births where the mode of delivery was an elective caesarean (n=16 325 (7.73%)) and births initiated by induction of labour (n=23 956 (11.34%)) were excluded from the data set for main analyses, thus leaving a total of 171 009 (80.94%) spontaneous births and acute caesareans, to be denoted ‘non-elective’ below.

Table 1.

Type of births in each obstetric clinic in the Capital Region of Denmark during 2000–2009, with the number and percentages of spontaneous births, acute caesarean sections after spontaneous onset of labour, births after induction of labour and elective caesarean sections

| Obstetric clinics | Births per clinic | Non-elective births (81%) |

Elective births (19%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous births | Per cent | Acute caesarean | Per cent | Induced births | Per cent | Elective caesarean | Per cent | ||

| Rigshospitalet | 35.657 | 19.144 | 54 | 5.740 | 16 | 6.345 | 18 | 4.428 | 12 |

| Hvidovre | 53.300 | 39.335 | 74 | 7.264 | 14 | 2.375 | 4 | 4.326 | 8 |

| Frederiksberg | 17.751 | 13.784 | 78 | 1.794 | 10 | 1.266 | 7 | 907 | 5 |

| Gentofte | 21.988 | 14.216 | 65 | 2.863 | 13 | 3.349 | 15 | 1.560 | 7 |

| Glostrup | 22.737 | 15.972 | 70 | 2.883 | 13 | 2.808 | 12 | 1.074 | 5 |

| Herlev | 23.967 | 17.352 | 72 | 2.800 | 12 | 2.680 | 11 | 1.135 | 5 |

| Hillerød | 35.890 | 23.209 | 65 | 4.653 | 13 | 5.133 | 14 | 2.895 | 8 |

| All seven clinics | 211.290 | 143.012 | 68 | 27.997 | 13 | 23.956 | 11 | 16.325 | 8 |

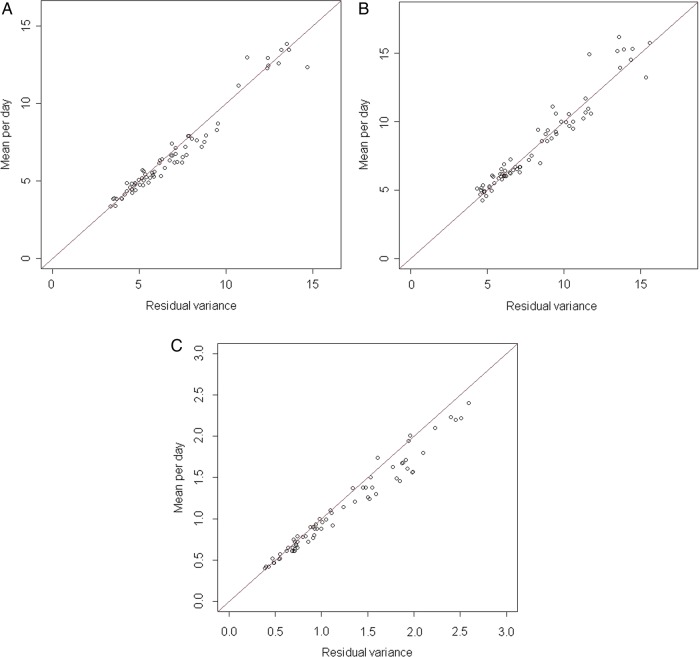

As mentioned in the introduction, the main problem in obstetrics management is the variation over days of the week. This variation is, to a large degree, a result of decisions by the obstetricians on how to distribute elective caesareans and electively induced labour over the days of the week.6 12 Preliminary descriptive analyses of the data clearly indicated that such policies varied considerably over the 10 years for each department and that the patterns were rather different between departments; however, overall, a mid-weekly peak in births remained even when ‘elective’ births were excluded (please see the online supplementary file, figures III–IX). The staffing required for these ‘elective’ births is a consequence of management decisions, and our focus here is on how to capture the primarily random variation in the ‘non-elective’ births. Owing to the strong heterogeneity in the day-to-day pattern for several of the involved departments over the 10 years under study, we performed a set of 70 one-way analyses of variance comparing the number of ‘non-elective’ births at each day of the week for each fixed combination of department (n=7) and year (n=10). The residual variances from these 70 analyses were compared to the annual mean number of births for each department. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed including all births and acute caesareans. As seen in figure 1, the residual variances are very close to the means, indicating a Poisson distribution of the variation in the number of ‘non-elective’ births for each day of the week around the yearly average for that day. We also see that the closeness of residual variance to the mean improves when we only look at the ‘non-elective’ births, while for the acute caesareans only there is a clear trend that the variance is larger than the mean, so-called overdispersion, which violates the assumption of Poisson distribution. In view of these findings, we focus on the ‘non-elective’ births in the following.

Figure 1.

Residual variance compared with the mean number of births per day for (A) ‘non-elective’ births, (B) all births and (C) acute caesarean sections.

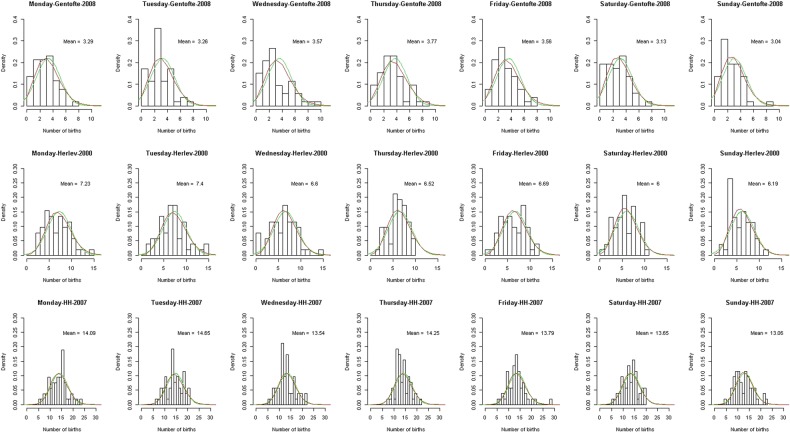

To illustrate our findings, three selected combinations of department and year, a small, medium and large clinic, were chosen. For each day of the week, a histogram shows the observed distribution of the 52 (53) numbers of births per day for that year with fitted normal distribution (red) and a fitted Poisson distribution was produced (green; figure 2). It is seen that there is a nice fit throughout of the Poisson distributions, and also that they are very close to the normal distributions with the same variance. This means that calculations of the likely variation in the number of ‘non-elective’ births can be based on the normal distribution with variance given by the average number of ‘non-elective’ births per day over the year.

Figure 2.

Exemplification of small (Gentofte), medium (Herlev) and large (Hvidovre Hospital, HH) obstetric clinics with the number of births at the x axis and density at the y axis with curves indicating the Poisson distribution (red) and the normal distribution (green).

For example, if at a particular department in a particular year the mean number of ‘non-elective’ births is 9, the residual variance is estimated to be 9 and SD as the square root of 9, that is, 3. Assume that the mean number of ‘non-elective’ births on Tuesdays for that department for that year is 10.5. In 95% of Tuesdays, the actual number of ‘non-elective’ births in that department will be in the interval between 10.5–3×1.96=4.6 and 10.5+3×1.96=17.4, while in 80% of Tuesdays there will be between 10.5–3×1.28=6.7 and 10.5+3×1.28=14.3 non-elective births. This model is suitable for estimating the daily number of births and planning of staffing in obstetric clinics, and the model is adequate to be used in smaller as well as larger clinics.

Discussion

The management of staffing in obstetric clinics is a difficult task, due to the relatively unpredictable nature of labour onset. Nowadays, many births are ‘elective’ births in the sense that elective caesarean sections or medically induced labour more or less governs the time of the week where the birth happens. It has been assumed that the day-to-day variation on the numbers of births fits a Poisson distribution,13 18 but suitable data on live births, including the mode of delivery, from a larger population have not been studied previously, thus limiting the means of studying day-to-day variation.7 13 Furthermore, the impact of elective obstetric intervention on the distribution has not been considered in any of the previous studies addressing birth variation.5–14 19

Interestingly, we find that even with the exclusion of births resulting from an obstetric intervention such as an elective caesarean or induction of labour, the remaining data still show significant weekly variation with a mid-weekly peak. As such, this variation might be ascribed not only to measurable obstetric interventions but also less tangible practices; for instance, the time of admittance of a woman in early stages of labour might depend on staff numbers, which vary during the week. Also, traditional non-medical methods of starting labour (hot baths, sexual intercourse, etc) might be less likely to be tried by mothers at the weekends.7

However, regardless of any obstetric practices or mothers’ practice, we found that the distribution of the remaining ‘non-elective’ births for each day of the week, each year and each department is still well approximated by a Poisson distribution, where the mean equals the variance. For the relevant parameter values, this Poisson distribution is indistinguishable from a normal distribution, where we may then estimate the variance from the mean. This means that calculations of the likely variation in the number of ‘non-elective’ births can be based on the normal distribution with variance given by the average number of ‘non-elective’ births per day over the year.

This provides us with a useful tool for planning of the staffing necessary to handle all births on a given weekday in an obstetric clinic. Elective caesarean sections are usually planned to be performed on specific weekdays with staff dedicated to this task. Births after induction of labour will also in most cases be planned. Combining the known number of elective births with the calculation of a 95% or 80% CI of ‘non-elective’ births on a given weekday gives a good possibility to avoid overstaffing or understaffing and utilise the available human resources to their best. For larger clinics where the mean number of ‘non-elective’ births for a given weekday may vary by more than 1–2 births, the relocation of staffing to ‘peak’ weekdays has the most to offer, but even smaller clinics can benefit from more concrete calculation, for example on how weekend staffing should be.

The fact that the distribution of ‘non-elective’ births is indistinguishable from a normal distribution provides a simple, but elegant, tool for planning of staffing in obstetric clinics and, used wisely, may prove a positive adjustment for work efficiency, cost and environment.

Conclusions

We may estimate the variance from the mean, as the Poisson distribution for these parameters is indistinguishable from a normal distribution. This model is suitable for estimating the variation in the daily number of ‘non-elective’ births and could be used for planning of staffing in obstetric clinics.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CMBG, NK, JT and ELL have all been involved in the conception of this study and the writing of this article. The statistical analysis has been carried out mainly by JT under the guidance of NK, ELL and CMBG. Coordination of the correspondence between authors has been taken care of by CMBG.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The formal two-way analyses of variances preceding and leading to the main analysis, a one-way analysis of variance comparing days of the week for each fixed combination of department7 and year10 described in the article, are available on request to anyone from the corresponding author. The informal descriptive analysis of the data has been included in the online supplementary file.

References

- 1.Sygehusfødsler og fødeafdelingernes størrelse 1982-2005 Nye tal fra Sundhedsstyrelsen [Hospital births and size at birth departments 1982-2005. New figures from the Danish Health and Medicines Authority]. Copenhagen: Danish Health and Medicines Authority, 2007. http://www.sst.dk/publ/tidsskrifter/nyetal/pdf/2007/03_07.pdf. Danish [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sygehusbehandling og Beredskab Specialevejledning for gynækologi og obstetrik [Hospital and Emergency Management. Guidelines for the specialty of gynecology and obstetrics] [database on the Internet]. Danish Health and Medicines Authority, 2011. http://www.google.dk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CC0QFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.sst.dk%2F~%2Fmedia%2FPlanlaegning%2520og%2520kvalitet%2FSpecialeplanlaegning%2FSpecialevejledninger_2010%2FSpecialevejledning_%2520gynaekologi_obstetrik.ashx&ei=HN5BUe3YLMWXO8vkgNgN&usg=AFQjCNHwTAn_VjRByL74GQSAq-mmLD4XYQ&sig2=Dgizs6-smdvyJnCuAnGtZw. Danish [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tal og analyse: Fødselsstatistikken 2011 [Numbers and analysis: Birthstatistics 2011]. Copenhagen. Danish Health and Medicines Authority; 2012. http://www.sst.dk/publ/Publ2012/03mar/Foedselsstatistik2011.pdf. Danish

- 4. Fødsler 1973– [Births 1973–] [database on the Internet]. Danish Health and Medicines Authority. http://www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Dataformidling/Sundhedsdata/Fodsler/Fodsler%201973.aspx. Danish.

- 5.Cohen A. Seasonal daily effect on the number of births in Israel. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat 1983;32:228–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtin SC, Park MM. Trends in the attendant, place, and timing of births, and in the use of obstetric interventions: United States, 1989–97. Natl Vital Stat Rep 1999;47:1–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacFarlane A. Variations in number of births and perinatal mortality by day of week in England and Wales. BMJ 1978;2:1670–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martins JM. Never on Sundays. Med J Aust 1972;1:487–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menaker W, Menaker A. Lunar periodicity in human reproduction: a likely unit of biological time. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1959;77:905–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odegard O. Season of birth in the population of Norway, with particular reference to the September birth maximum. Br J Psychiatry 1977;131:339–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borst LB, Osley M. Letter: holiday effects upon natality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975;122:902–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rindfuss RR, Ladinsky JL, Coppock E, et al. Convenience and the occurrence of births: induction of labor in the United States and Canada. Int J Health Serv 1979;9:439–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawe E, MacFarlane A. Daily and seasonal variation in live births, stillbirths and infant mortality in England and Wales, 1979–96. Health Stat Q 2001:5–15 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osley M, Summerville D, Borst LB. Natality and the moon. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1973;117:413–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang XM. A planning model for requirement of emergency beds. IMA J Math Appl Med Biol 1995;12:345–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao EP, Tung GG. Bed allocation in a public health care delivery system. Manag Sci 1981;27:507–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pike MC, Proctor DM, Wyllie JM. Analysis of admissions to a casualty ward. Br J Prev Soc Med 1963;17:172–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkwood BR. The Poisson distribution. Essentials of medical statistics. Blackwell Science, 1988:125–7 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fallenstein F, Haener W, Huch A, et al. The influence of the moon on deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;148:119–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.