Abstract

Responsible for the Irish potato famine of 1845–49, the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora infestans caused persistent, devastating outbreaks of potato late blight across Europe in the 19th century. Despite continued interest in the history and spread of the pathogen, the genome of the famine-era strain remains entirely unknown. Here we characterize temporal genomic changes in introduced P. infestans. We shotgun sequence five 19th-century European strains from archival herbarium samples—including the oldest known European specimen, collected in 1845 from the first reported source of introduction. We then compare their genomes to those of extant isolates. We report multiple distinct genotypes in historical Europe and a suite of infection-related genes different from modern strains. At virulence-related loci, several now-ubiquitous genotypes were absent from the historical gene pool. At least one of these genotypes encodes a virulent phenotype in modern strains, which helps explain the 20th century’s episodic replacements of European P. infestans lineages.

Phytophthora infestans caused the potato famine in the nineteenth century. Martin et al. sequence the nuclear genomes of five archival samples of the pathogen and compare these to extant specimens allowing the reconstruction of the evolutionary history of P. infestans.

Phytophthora infestans caused the potato famine in the nineteenth century. Martin et al. sequence the nuclear genomes of five archival samples of the pathogen and compare these to extant specimens allowing the reconstruction of the evolutionary history of P. infestans.

Phytophthora infestans was responsible for the Irish potato famine, which led to the death and emigration of over two million Irish people, and subsequent outbreaks of potato late blight that devastated European harvests throughout the latter half of the 19th century1,2. Although this catastrophe initiated efforts to breed more resistant potatoes3, P. infestans still remains a threat to potato and tomato production worldwide4. Global damage and control costs exceed US$6.2 billion per year, with over $1 billion spent on fungicides alone5.

Migration mediated by human activity has had an important role in the historic and recent spread of potato late blight from the New World6,7. It was initially proposed that the introduction of a single genotype of P. infestans (RFLP genotype US-1, mtDNA haplotype Ib) caused the 19th-century epidemics and that this clonal lineage dominated extra-Mexican populations until recently8. However, genetic analyses exploiting infected potato leaves and tubers from 19th century herbaria specimens indicated that the famine-era disease in the United States, Ireland and Europe was caused by the Ia mitochondrial lineage of P. infestans and suggested that the Ib lineage was introduced later, in the mid-20th century9,10. In the latter half of the 20th century, this Ib lineage was rapidly displaced in both Europe and the United States11,12,13 by more virulent lineages that possessed fitness advantages including fungicide resistance and increased aggressiveness7,12,14,15.

P. infestans is a hallmark example of an organism with rapid evolutionary potential16,17,18. This adaptability is fostered by its arsenal of secreted RXLR-motif effector proteins that facilitate infection by manipulating host physiology after translocation into host cells. Among these RXLR effectors are avirulence (avr) proteins that are recognized by corresponding resistance (R) proteins in the host, initiating the hypersensitive defense response19. R genes derived from wild potato (Solanum demissum) were deployed widely in breeding programs in the early 20th century20, but pathogen populations quickly overcame them21,22,23,24. Consequently, such potatoes are rarely planted today.

To provide a baseline for understanding the nature of temporal changes in the P. infestans genome, we generated genomic reads by shotgun sequencing DNA extracts of blight-infected potato leaves from historic herbarium specimens collected during the initial 1845 outbreaks of disease near Audenarde, Belgium1 and an additional sample from Britain25, and later samples from Germany, Denmark and Sweden (1876–1889). We also sequenced three modern isolates (RFLP genotypes US-8, US-22 and US-23) currently causing disease in North America13. These data are compared with the published reference genome sequence of the European strain T30-4 (ref. 26) and the European ‘blue 13’ strain 06_3928 (13_A2)12. To our knowledge, this work represents the first genome-level analysis of a eukaryote pathogen from a historical collection. We observe distinct nuclear genotypes in historical samples that imply multiple introductions to Europe before the 20th century. We also report a number of genes that were likely absent in the historical period, many of which are effectors related to infection of the modern S. tuberosum host. Specifically, at loci associated with virulence, a number of diploid genotypes present in all modern isolates are entirely absent from the historical gene pool. At the well-known effector gene Avr3a, only the avirulent AVR3aKI allele is detected in historical strains, thereby elucidating at least one mechanism by which the aggressive lineages of the 20th century completely replaced historical genotypes introduced just before the famine.

Results

High-throughput sequencing of samples

Three modern US isolates RS2009P1 (US-8), IN2009T1 (US-22) and BL2009P4 (US-23) were each independently sequenced to a high depth of at least 28-fold mean coverage of the ~240 Mbp P. infestans strain T30-4 reference genome (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Table S2). In addition, the 1845 sample from Belgium and the 1889 sample from Germany were sequenced, respectively, to 16-fold and 22-fold mean coverage. The special nature of these specimens—a pathogen embedded within poorly preserved tissues of its host—presents unique technical challenges10, not least of which are trace amounts of endogenous target DNA, post-mortem DNA damage and ambiguous mapping of short shotgun sequence reads to repetitive and G/C-rich regions of the genome (Supplementary Figs S1–S5). Consistent with our expectations of extensive fragmentation of the DNA extracted from dried leaves collected 122–167 years ago, sequence lengths of DNA inserts mapped to the P. infestans T30-4 reference genome range between 52–79 bp in historical samples Pi1845A (52 bp), Pi1845B (59 bp), Pi1876 (79 bp), Pi1882 (72 bp) and Pi1889 (75 bp; Supplementary Fig. S2). After normalizing each library by the number of reads mapped to the P. infestans genome, the overall mean insert size for historical samples is 67 bp.

Phylogenetic analysis of nuclear genomes

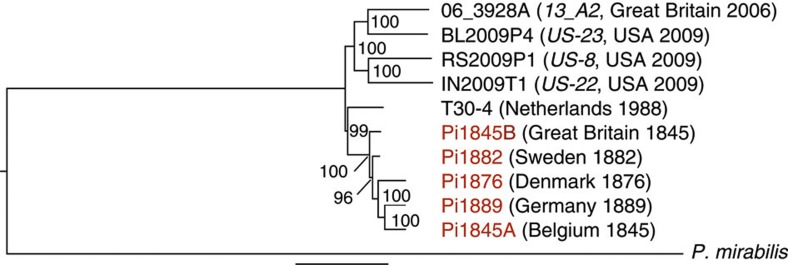

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of the uniquely mappable components of these genomes indicates that the historical European samples form a highly supported monophyletic clade that is distinct from modern isolates (Fig. 1, Supplementary Methods). The resequenced strain T30-4 sample occupies an intermediate position between the other modern samples and the historical European samples. Strain 06_3928A (13_A2) is most closely related to strain BL2009P4 (US-23) collected in Pennsylvania, USA. Samples from the modern and historical time periods differ by an estimated 120,359 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within nuclear gene-encoding regions (Supplementary Data 1). Of these SNPs, 24,040 are unique to the historical samples Pi1845A or Pi1889, and 12,893 SNP genotypes are not shared between the two. In a multi-locus phylogenetic analysis, the historical samples clustered with diverse isolates from the United States, Mexico, Ecuador and Europe (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 1. Maximum-likelihood phylogram of P. infestans genomes from the first historic outbreaks of disease and later outbreaks.

Nodes are labelled with their support values from 100 bootstrap replicates. The scale bar indicates a branch length of 0.2 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Gene content analysis

An analysis of the presence of modern strain T30-4 reference genes in historical samples based on read mapping shows that 21 of the reference genes absent in Pi1889 are detected with partial coverage in at least one of the four older historical samples (Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Figs S7–S11). They include six secreted RXLR effectors, an NPP1-like pseudogene and two proteins of unknown function that are among the most induced during infection of potato by strain T30-4.

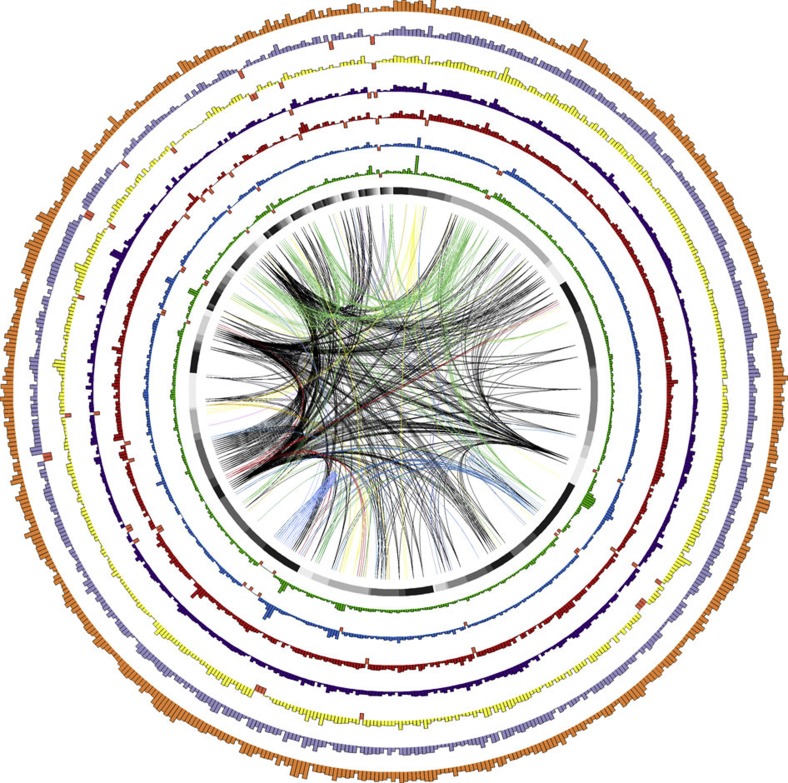

The analysis of modern strain T30-4 reference genes in resequenced samples also shows that genes tend to be deleted from gene-sparse regions of the P. infestans genome, which are enriched for effectors (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S12). Indeed, many of the differentially absent RXLR and CRN effectors that we have identified here belong to clusters of homologous genes that are more likely to be similar or redundant in function (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S13, Supplementary Fig. S14).

Figure 2. Visualization of sequencing coverage distribution across all reference RXLR effectors.

Bar heights represent the mean-normalized coverage of 583 reference RXLR effector genes in the resequenced genome of a particular sample. Genes are arranged according to their 5′ to 3′ physical position on the T30-4 reference genome assembly supercontigs. The black section at the top of the inner ring represents the eight RXLRs contained on supercontig 1. RXLRs in supercontigs 2, 3, … 4802 follow in clockwise fashion, each represented by a different shade of grey. Historical samples Pi1845A (green) and Pi1889 (blue) are plotted along the two inner rings. The resequenced reference strain T30-4 (orange) is plotted in the outer ring, while the remaining inner rings represent modern isolates IN2009T1 (US-22; red), BL2009P4 (US-23; purple), RS2009P1 (US-8; yellow) and 06_3928A (13_A2; light purple). Orange bars extending below the axis indicate genes undetected in a particular sample (Supplementary Table S3). The central links connect a gene absent in at least one resequenced genome to all other members of its tribe, with a unique colour for each tribe.

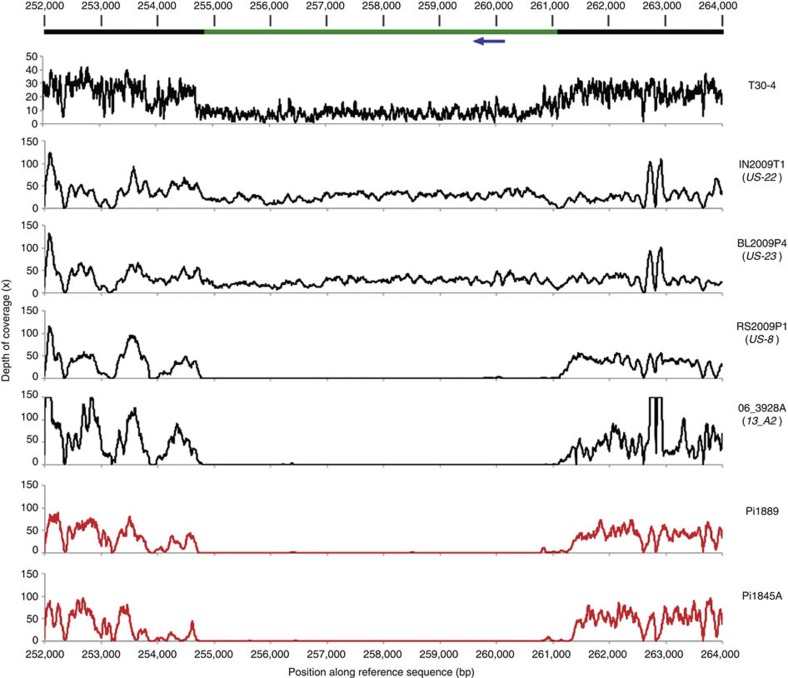

Figure 3. Read depth of coverage around a deleted RXLR effector gene.

The top bar represents the T30-4 strain reference genome assembly sequence for supercontig 66. The green portion of the bar represents a ~6-kbp region deleted in the lower four samples. The blue arrow represents the position of RXLR effector PITG_18215, which is absent from samples with the deletion. Data for the historical samples are plotted in red. Coverage of this region in strain T30-4 is reduced to ~50% of the genome-wide mean. In T30-4, this region is likely either hemizygous or a duplication erroneously absent from the genome assembly. In any case, the sharply defined borders and consistent lack of coverage over the entire deleted region (spanning the length of ~85 successive 70-bp reads) in all samples are conclusive evidence that the region is deleted in four of the resequenced samples.

In historical samples, a considerable number of genes relevant to plant pathogenesis pathways are absent (Supplementary Table S3). Six genes absent in Pi1889 were demonstrated to be differentially expressed during infection of potato by reference strain T30-4 (refs 26, 27). Of the 26 genes absent in Pi1889 that have an annotated function, 23 are implicated in plant pathogenesis26. Results are similar for Pi1845A. RXLR effectors made up a larger portion of absent reference genes in Pi1845A and Pi1889 than in aggressive, introduced strains from present-day Europe and the United States, including the recently sequenced ‘Blue 13’ isolate 06_3928A (13_A2) from Great Britain (Supplementary Fig. S15).

Assembly and prediction of novel RXLR effectors

To complement our catalogue of absent genes, we searched the resequenced genomic data from our high-coverage samples for novel, non-reference RXLR effector genes. For each sample we performed de novo assembly of reads unmapped to the T30-4 reference genome, and then searched the assembled contig sequences for novel coding sequences containing the RXLR motif (Supplementary Table S4). This search discovered five new RXLR genes among the modern US isolates, but did not reveal any in the historical samples Pi1845A or Pi1889 (Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Table S6).

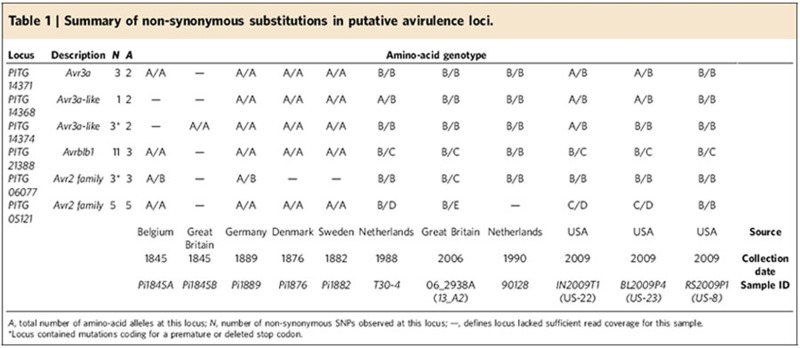

Temporal differences at virulence loci

Among avr genes, deletion, pseudogenization, transcriptional silencing, copy number variation and diversification of amino-acid sequence have all been proposed as mechanisms for evading recognition by the host12,28. We surveyed the amino-acid sequences of genes with avr-related annotations to identify candidates for further investigation into virulence differences between historical and modern lineages. The virulent AVR3aE80/M103 allele of P. infestans RXLR effector Avr3a, which is ubiquitous in diverse global populations29 and is present in all modern isolates in our analysis, is absent from all historical samples with coverage of this locus (Table 1). Only the avirulent AVR3aK80/I103 allele is detected.

Table 1. Summary of non-synonymous substitutions in putative avirulence loci.

|

Directly parallel cases are also observed at two genes near and closely related to Avr3a (PITG_14368 and PITG_14374), where the historical samples shared homozygous alleles, while all modern strains possessed one or two alleles encoding an alternative amino-acid sequence. Similar phenomena, where all the historical samples shared a single amino-acid genotype that was absent in modern isolates, are observed in PITG_21388 (Avrblb1), PITG_06077 (Avr2 family) and PITG_05121 (Avr2 family)22. These results are summarized (Table 1), and amino-acid sequences are provided (Supplementary Table S7).

Discussion

Our nuclear genome sequence analysis of famine-era and later historical P. infestans samples from Europe demonstrates that they formed a phylogenetic clade that does not cluster with any modern isolates yet sequenced. In addition, we show that these genotypes were closely related and differed substantially from isolates now present in both the United States and Europe. These results are consistent with the hypothesis4,8 of introduction from a New World source of limited genetic diversity. In contrast to the three modern strains from the United States, contemporary European isolates did not segregate into a single lineage, indicating that introductions into Europe after the first outbreak likely came from multiple genetic sources that were closely related7,8. Historical samples clustered with diverse isolates from Mexico, Ecuador and the United States in our multi-gene phylogenetic analysis of available global isolates, but further investigation into the genomes of historical and globally diverse samples is needed to draw conclusions about the geographic origin of the famine-era P. infestans introductions.

The large number of nuclear-coding region SNPs distinguishing the two high-coverage historical samples from each other suggest substantial evolutionary divergence of P. infestans genomes within Europe in the 19th century. The gene content analyses also provide evidence that genetically distinct late blight lineages were present in Western Europe by 1889, but definitive confirmation would require more complete recovery of the nucleotide sequences of these genes from other historical isolates. Tentatively, however, we argue that if only a single clonal lineage was introduced to Europe in 1845, this would be an illustrative example of rapid evolution, with <50 years of clonal reproduction30 through seasonal population bottlenecks and varied regional selective pressures leading to gene loss. Although mutation rates in oomycetes are unknown, this rapid pace of divergence within a single clonal lineage8,14 indicates that we cannot rule out an alternative hypothesis—that multiple closely related lineages were introduced to 19th-century Europe.

Genes from the modern reference genome assembly tend to be deleted from rapidly evolving, gene-sparse regions of the genomes of the resequenced samples we analysed. These regions are enriched for effectors and evolve more quickly than gene-dense regions26,28. Indeed, many of the differentially absent RXLR and CRN effectors that we have identified here belong to clusters of homologous genes that are more likely to be similar or redundant in function. There is likely to be less pressure to conserve all members of these expanded tribes, thus contributing to the plasticity of these and other effector gene families and their genomic surrounds.

We also show that historical populations had a repertoire of secreted proteins different from that observed now. Reference genes absent from the historical genomes were more likely to be RXLR effectors than genes absent from aggressive, introduced strains from present-day Europe and the United States. Genes and alleles absent in historical samples that are now recognized as important for infection of potato may relate to genomic changes that enabled the successive 20th century replacements of Europe’s historical lineages with new strains better suited to the changing selective conditions of European potato fields.

We detected only the avirulent AVR3aK80/I103 allele in historical samples. Potato gene R3a, which recognizes Avr3a during infection, was not introduced to potato breeding stocks until the 20th century21,24. Thus, our data support the previously suggested hypothesis that the avirulent allele gave rise to the virulent allele under positive selection30. Given our observations of similar phenomena at other putative avr loci, they may illustrate examples of how the P. infestans effector genes present in circulating lineages rapidly changed following the introduction of diverse R genes in efforts to breed more resistant potato cultivars. This would parallel known examples of genome evolution as a response to human actions in other eukaryote pathogens that employ effectors, like the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, whose proteome shares in common with P. infestans motifs for protein translocation.

This catalogue of genes that were historically absent or later influenced by natural selection provides direction for further research into the functional causes of the episodic replacements that have occurred in the global migrations of P. infestans. Our data indicate at least two distinct lineages of P. infestans in 19th-century Europe and thus emphasize the role of migration in shaping the population history of this plant pathogen. Future efforts to understand the migratory history of this destructive pathogen and to further characterize the number and source of lineages that were present historically in Europe would benefit from focusing on sequencing more early-outbreak samples to high depth, should they become available.

Methods

Selection of historical samples

Five historic herbarium specimens from two different collections were chosen for analysis (Supplementary Table S1). These dried potato leaves with lesions produced by P. infestans represent material from early disease outbreaks in the British Isles, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden and Germany, and date from 1845–1889 (Supplementary Fig. S1). The samples included the oldest known specimens from the epidemics of potato late blight that occurred in Europe9. From each individually wrapped potato specimen envelope, a small (~5 mm in diameter) piece of dried tissue from the lesion edge was placed in a sterile microfuge tube for later DNA extraction using a modified CTAB procedure10. Extreme care was taken to avoid physical contact between specimens. Work with the herbarium specimens was performed in the North Carolina State University Phytotron Containment Facility Laboratory, which was equipped with separate supplies, reagents and equipment having no history of research involving P. infestans.

Primers PINF and HERB1 were used to amplify and sequence a portion of the internal transcribed spacer region 2 of ribosomal DNA to confirm that the specimens were infected with P. infestans10. Sequence analysis of the amplified portions of the mtDNA genes using methods previously described identified the mitochondrial haplotype9,10.

All historical samples were confirmed to possess mtDNA haplotype Ia31 by examining the consensus sequence at these loci generated on the Illumina platform.

Library preparation and sequencing of historical samples

All pre-PCR manipulations were performed in the dedicated ancient DNA laboratories at the Centre for GeoGenetics, University of Copenhagen. Extracted DNA from samples Pi1889, Pi1876 and Pi1882 were built into Illumina libraries with a NEBNext DNA Library Preparation for Illumina kit. Extracted DNA from samples Pi1845A and Pi1845B were built into Illumina libraries with a NEBNext DNA Library Preparation for Roche/454 kit. The manufacturers’ protocol was followed, with the exclusion of the fragmentation step and reduction of adapter concentration in the adapter ligation step.

After library construction, unique index sequences were added through PCR. Initial DNA amplification was carried out through 10 cycles of PCR in a total volume of 50 μl, containing 5 units Taq Gold polymerase, 1 × PCR Gold buffer, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 50 μg BSA, 1 mM each dNTP, 0.5 μM inPE1.0 forward primer, 10 nM inPE2.0 reverse primer, 0.5 μM unique index primer and 5–15 μl DNA template (sample-dependent). DNA was further amplified through an additional 10–15 cycles (sample-dependent) by using 5 μl first-round PCR product as the template in a second round of PCR carried out in a total volume of 50 μl and under same conditions as the first round except that the primer inPE2.0 was not included.

Before sequencing, DNA fragment size selection was carried out with 2% agarose gels for samples Pi1889, Pi1876 and Pi1882, and with a Caliper LabChip XT for samples Pi1845A and Pi1845B. All products were purified with Qiagen QIAquick gel extraction kit before sequencing.

An initial quality assessment was performed on sample Pi1889 through sequencing 75 bp Single Reads on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. Subsequent sequence data on other samples were generated using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 using both Single Read 100 bp and Paired End 100 bp chemistries (Supplementary Table S2).

Library preparation and sequencing of modern isolates

Mycelia from three modern US isolates RS2009P1 (US-8), IN2009T1 (US-22) and BL2009P4 (US-23) were grown in pea broth and DNA was similarly extracted with a CTAB procedure. Library construction for these strains was performed at the University of North Carolina High-Throughput Sequencing Facility using a TruSeq DNA library preparation kit (Illumina). Each library was barcoded with a unique index sequence. Library quality assessment was performed on the Experion (Biorad) automated electrophoresis system and fluorometric DNA quantification was estimated by Qubit (Invitrogen). All three libraries were pooled and sequenced in a multiplex Paired End 100 cycles configuration on a single lane of the HiSeq 2000 flowcell. Data demultiplexing was performed by Illumina pipeline version 1.7.0 (Supplementary Table S2).

Read trimming and mapping

Genomic sequence reads from P. infestans strains 90128 and T30-4 (submissions SRS115105, SRP003617 and SRP000883), and P. mirabilis strain PIC99114 (accession SRP003618) were obtained from the Sequence Read Archive (sra.dnanexus.com). Genomic sequence reads from isolate 06_3928A (13_A2) were obtained directly from the authors12.

Adapter sequence and low quality bases were trimmed from the 3′ ends of DNA reads with the software AdapterRemoval version 3 (ref. 32) using a mismatch rate of 0.333. Paired reads overlapping by at least 11 bp were collapsed into a single read with a re-calibrated base quality. Reads shorter than 25 bp after adapter sequence removal were discarded.

Mapping to the complete P. infestans T30-4 reference genome was performed with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) version 0.5.9 (ref. 33) with seeding deactivated and otherwise default settings. PCR duplicates were removed conservatively with the software Picard version 1.66’s MarkDuplicates function, which removes all but one of reads whose 5′ and 3′ ends map to the same coordinates in the reference genome. Read alignments to the reference genome were optimized with the RealignerTargetCreator and IndelRealigner tools included in the software Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) version 1.3 (ref. 34).

The reference genome assembly and annotation of P. infestans strain T30-4 was obtained from the Broad Institute’s P. infestans Database ( www.broad.mit.edu).

Reads unmapped to the P. infestans reference genome assembly were extracted from Binary Sequence/Alignment Map (BAM) files and then mapped to the complete S. tuberosum reference genome assembly version 3 DM sequence35, which was obtained from the Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium public data release (solanaceae.plantbiology.msu.edu).

Analysis of metagenomic composition of unmapped reads

To investigate the metagenomic composition of the historical DNA libraries of samples Pi1845A and Pi1889, we randomly sampled 1 M unique reads from those not mapped to either of the P. infestans or S. tuberosum reference genomes. The software megaBLAST version 2.2.21 (ref. 36) was used to align these sequences against the contents of the NCBI non-redundant nucleotide sequence database with an E-value cutoff of 0.0001. The best hit in the database was used for each input read. The software MEGAN version 4.70.4 (ref. 37) was used to assign the best matches to phylogenetic groups. The portion of the two libraries that could be classified was similar, with ~80% of reads having no hits in the database (Supplementary Fig. S5). Of the reads with close BLAST hits, the majority matched Phytophthora sequences in Pi1845A and bacterial sequences in Pi1889.

Analysis of post-mortem DNA damage

BAM files containing reads aligned to the P. infestans T30-4 reference genome were analysed with the software mapDamage version 0.3.6 (ref. 38) to confirm the existence of nucleotide misincorporations characteristic of the degradation in ancient DNA39,40,41,42 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Report of polymorphism in gene-coding sequences

For samples Pi1845A, Pi1889, RS2009P1 (US-8), IN2009T1 (US-22) and BL2009P4 (US-23), SNPs were tallied at all non-N reference genome positions annotated as coding sequence. SNPs were included in the final tally if they surpassed a Q20 variant quality score and the variant position was covered by at least six uniquely mapped reads with MAPQ score ≥25 after PCR duplicate removal. We report 178,734 non-reference SNP positions (Supplementary Data 1). We detected 82,415 of these SNPs in the two historical samples and 154,694 of these SNPs in the three modern samples.

Author contributions

M.D.M. and M.T.P.G. led the genome sequencing of historic samples and data analyses with assistance from E.C., J.A.S., M.L.Z., P.F.C., A.S.O., N.W., L.O., E.W. and S.Y.W.H. J.B.R. provided DNA of the historic samples. J.H., P.M. and J.B.R. coordinated Illumina sequencing of the three modern genotypes. F.S.D. and A.K. provided bioinformatics support. M.D.M., M.T.P.G. and J.B.R. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. M.T.P.G. and J.B.R. contributed equally as senior authors to the manuscript.

Additional information

Accession codes: High-throughput sequencing reads generated for this study were deposited on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under the accession code PRJEB0415.

How to cite this article: Martin, M. D. et al. Reconstructing genome evolution in historic samples of the Irish potato famine pathogen. Nat. Commun. 4:2172 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3172 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S15, Supplementary Tables S1-S7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

List of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) detected in P. infestans samples Pi1845A, Pi1889, RS2009P1 (US-8), IN2009T1 (US-22) or BL2009P4 (US-23).

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible thanks to generous support by Lundbeck Foundation Grant R52-A5062 to M.T.P.G. Funding was also provided in part by NIH/NIAID R37 Grant AI039115-14 to J.H. and USDA NRI no. 2006-55319-16550 to J.B.R. For their advice and valuable technical assistance, we thank the staff of the Danish National High-Throughput DNA Sequencing Center, and our colleagues A. Albrechtsen, A. Ginolhac, R. Fonseca, M. Rasmussen, S. Lindgreen, E. Lassiter and A. Saville. We would like to express our appreciation to herbaria at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, England (K), the National Fungus Collections, USDA, Beltsville, Maryland (BPI), and the Museum of Evolutionary Botany, University of Uppsala, Sweden for providing access to specimens for this research. We thank S. Kamoun and J. Win for their willingness to share data and assist with its analysis. We also acknowledge the helpful criticisms and encouragement from three anonymous reviewers.

References

- Bourke P. M. Emergence of potato blight. Nature 203, 805–808 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Woodham-Smith C. The Great Hunger Old Town Books (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning D. R. Potato introductions and breeding up to the 20th century. N. Phytol. 94, 385–402 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Fry W. Phytophthora infestans: the plant (and R gene) destroyer. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9, 385–402 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkort A. J. et al. Societal costs of late blight in potato and prospects of durable resistance through cisgenic modification. Potato Res. 51, 47–57 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Goméz-Alpizar L., Carbone I. & Ristaino J. B. An Andean origin for Phytophthora infestans inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3306–3311 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin S. B., Cohen B. A., Deahl K. L. & Fry W. E. Migration from Northern Mexico as the probable cause of recent genetic changes in populations of Phytophthora infestans in the United States and Canada. Phytopathology 84, 553–558 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin S. B., Cohen B. A. & Fry W. E. Panglobal distribution of a single clonal lineage of the Irish potato famine fungus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11591–11595 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May K. J. & Ristaino J. B. Identity of the mitochondrial DNA haplotype(s) of Phytophthora infestans in historical specimens from the Irish potato famine. Mycol. Res 108, 171–179 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristaino J. B., Groves C. T. & Parra G. PCR amplification of the irish potato famine pathogen from historic specimens. Nature 41, 695–697 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl H. R. & Iselin K. Strains of Phytophthora infestans with A2 mating type behavior. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 83, 529–530 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Cooke D. E. L. et al. Genome analyses of an aggressive and invasive lineage of the Irish potato famine pathogen. PLoS. Pathog. 8, e1002940 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C. H. et al. Recent genotypes of Phytophthora infestans in eastern USA reveal clonal populations and reappearance of mefenoxam sensitivity. Plant Dis. 96, 1323–1330 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman L. J. et al. A second world-wide migration and displacement of Phytophthora infestans? Plant Pathol 40, 422–430 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Fry W. E., Goodwin S. B., Matuszak J. M., Spielman L. J. & Milgroom M. G. Population genetics and intercontinental migrations of Phytophthora infestans. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 30, 107–129 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang R. H., Tripathy S., Govers F. & Tyler B. M. RXLR effector reservoir in two Phytophthora species is dominated by a single rapidly evolving superfamily with more than 700 members. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4874–4879 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenbrock E. H. & MacDonald B. A. The origins of plant pathogens in agro-ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 75–100 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleeshouwers V. G. et al. Understanding and exploiting late blight resistance in the age of effectors. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 49, 507–531 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H. H. Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9, 275–296 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Salaman R. N. Proc IVth International Congress of Genetics p.397 (1911). [Google Scholar]

- Black W. A genetical basis for the classification of strains of Phytophthora infestans. Proc. Royal Soc. Ed. B 65, 36–51 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy E. M. et al. Presence/absence, differential expression and sequence polymorphisms between PiAVR2 and PiAVR2-like in Phytophthora infestans determine virulence on R2 plants. N. Phytol. 191, 763–776 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleeshouwers V. G. et al. Effector genomics accelerates discovery and functional profiling of potato disease resistance and Phytophthora infestans avirulence genes. PLoS One 3, e2875 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wastie R. In:Phytophthora Infestans, the Cause of Late Blight of Potato (eds Ingram D., Williams P.) pp.193–224 (London, Amsterdam (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley M. J. Observations botanical and physiological on the potato murrain. J. Hort. Soc. 1, 9–34 (1846). [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J. et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature 461, 393–398 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun S. A catalogue of the effector secretome of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 41–60 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele S. & Kamoun S. Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 10, 417–430 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong M. R. et al. An ancestral oomycete locus contains late blight avirulence gene Avr3a, encoding a protein that is recognized in the host cytoplasm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7766–7771 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen J. E. & Andersson B. What is the evidence for sexual reproduction of Phytophthora infestans in Europe? Plant Pathol. 62, 485–491 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ristaino J. B., Hu C. H. & Fitt D. L. Evidence for presence of the founder Ia mtDNA haplotype of Phytophthora infestans in 19th century potato tubers from the Rothamsted archives. Plant Pathol. 62, 492–500 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lindgreen S. Adapter removal: easy cleaning of next generation sequencing reads. BMC Res. Notes 5, 337 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. & Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PGSC et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Schwartz S., Wagner L. & Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Computat. Biol. 7, 203–214 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H., Mitra S., Ruscheweyh H.-J., Weber N. & Schuster S. C. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN 4. Genome Res. 21, 1552–1560 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginolhac A., Rasmussen M., Gilbert M. T., Willerslev E. & Orlando L. mapDamage: testing for damage patterns in ancient DNA sequences. Bioinformatics 27, 2153–2155 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pääbo S. Ancient DNA: extraction, characterization, molecular cloning, and enzymatic amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1939–1943 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A. J., Willerslev E., Wiuf C., Mourier T. & Arctander P. Statistical evidence for miscoding lesions in ancient DNA templates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 262–265 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofreiter M., Serre D., Poinar H. N., Kuch M. & Pääbo S. Ancient DNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 353–359 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M. T. et al. Characterization of genetic miscoding lesions caused by postmortem damage. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 48–61 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S15, Supplementary Tables S1-S7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

List of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) detected in P. infestans samples Pi1845A, Pi1889, RS2009P1 (US-8), IN2009T1 (US-22) or BL2009P4 (US-23).