Abstract

The NAD-synthesising enzyme Nmnat2 is a critical survival factor for axons in vitro and in vivo. We recently reported that loss of axonal transport vesicle association through mutations in its isoform-specific targeting and interaction domain (ISTID) reduces Nmnat2 ubiquitination, prolongs its half-life and boosts its axon protective capacity in primary culture neurons. Here, we report evidence for a role of ISTID sequences in tuning Nmnat2 localisation, stability and protective capacity in vivo. Deletion of central ISTID sequences abolishes vesicle association and increases protein stability of fluorescently tagged, transgenic Nmnat2 in mouse peripheral axons in vivo. Overexpression of fluorescently tagged Nmnat2 significantly delays Wallerian degeneration in these mice. Furthermore, while mammalian Nmnat2 is unable to protect transected Drosophila olfactory receptor neuron axons in vivo, mutant Nmnat2s lacking ISTID regions substantially delay Wallerian degeneration. Together, our results establish Nmnat2 localisation and turnover as a valuable target for modulating axon degeneration in vivo.

The NAD-synthesising enzyme Nmnat2 is a critical, endogenous survival factor for axons. Specific depletion of Nmnat2 in primary culture axons induces spontaneous degeneration that is rescued by expression of WldS, suggesting a constant supply of Nmnat2 from the cell body into axons is required to ensure axon survival1. Similarly, peripheral nerve defects and neonatal mortality in Nmnat2 gene-trap mice are rescued by homozygous expression of WldS, strongly suggesting a role for Nmnat2 in axon maintenance in vivo2. Due to its very short half-life, levels of Nmnat2 distal to an injury decline rapidly, prior to fast Wallerian degeneration1. Similarly, depletion of axonal Nmnat2 distal to an obstruction could account for degeneration when axonal transport is blocked. Delayed Wallerian degeneration, as achieved by expression of the WldS protein3 or by axonally targeted Nmnat14,5, is the result, at least in part, of a much longer half-life of these Nmnat isoforms compared to Nmnat2, meaning that they can substitute the critical NAD-synthetic enzyme activity to keep axons alive despite the decline in levels of Nmnat21. However, due to the requirement for ectopic expression of an introduced protein, the clinical usefulness of re-targeted forms of Nmnat1 (such as WldS) is limited. In contrast, modulation of the turnover, enzymatic activity or delivery of the endogenous survival factor, Nmnat2, is a much more promising avenue to address axon degeneration during ageing and in disease. Further supporting a pro-survival function of Nmnat2 are its reported protective effects against injury-induced degeneration in live zebrafish6 and mouse primary culture axons1,7 as well as against neurodegeneration in a tauopathy mouse model8.

Nmnat2 is extremely labile, undergoes K48 poly-ubiquitination9 and its turnover is at least partially mediated by the ubiquitin proteasome system1. Accordingly, inhibition of the ubiquitin proteasome system delays the onset of Wallerian degeneration in cut primary culture axons10, potentially by stabilising Nmnat2 levels. Additionally, a recent study reported Drosophila Nmnat (dNmnat) as a potential downstream target of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Highwire. In the absence of Highwire, dNmnat as well as transgenic mouse Nmnat2 are stabilised, resulting in significant protection of injured axons11. Furthermore, there is recent evidence showing that the mammalian homologue of Highwire, PhrI, regulates turnover of Nmnat2 in mammalian axons. Loss of PhrI leads to increased levels of virally-transduced Nmnat2 and delays axon degeneration after injury in mouse peripheral axons12. Thus, modulation of Nmnat2 turnover presents a potentially promising target for delaying axon degeneration.

We recently reported that Nmnat2 is transported into primary culture axons by means of a Golgi-derived axonal transport vesicle population with which it associates through palmitoylation of a double-cysteine motif. This palmitoylation site is located in the exon 6-encoded region of Nmnat2, at the centre of the isoform-specific targeting and interaction domain (ISTID)13. Interestingly, however, we found that dissociation from transport vesicles through loss or mutation of the central, exon 6-encoded ISTID region enhances the ability of overexpressed Nmnat2 to preserve primary culture neurites after axotomy. This increased protective capacity was at least in part due to reduced levels of ubiquitination and an increased half-life of mutant, cytosolic Nmnat2 variants, suggesting modulation of Nmnat2 subcellular localisation as a means to enhance Nmnat2 half-life and protective capacity9.

The Wallerian degeneration phenotype after overexpression in primary culture has not always translated into efficacy in vivo14,15,16, and Wallerian degeneration in mouse sciatic nerve takes around four times longer than for injured neurites in primary culture15,17. Thus it is important to confirm some of our key primary culture findings in vivo. Here we report evidence for a role for ISTID regions in tuning Nmnat2 localisation, turnover and protective capacity in transgenic mice and Drosophila in vivo. Using mice expressing wild-type Nmnat2 tagged with a modified yellow fluorescent protein (Nmnat2-Venus) or mutant Nmnat2Δex6-Venus, we find that loss of its central ISTID region leads to a diffuse, non-vesicular localisation of Nmnat2 in peripheral nerves. Confirming our previous observations, we also find evidence for an increased half-life of Nmnat2Δex6-Venus compared to Nmnat2-Venus, suggesting, as the two are closely linked in primary culture9, a role for Nmnat2 subcellular localisation in modulating its turnover in vivo. Additionally, we confirm that overexpression of a stabilised form of Nmnat2 delays Wallerian degeneration in mouse peripheral nerves. Finally, we show that, while wild-type Nmnat2 fails to protect Drosophila olfactory axons, deletion of ISTID regions, transforms Nmnat2 into a highly protective molecule for Drosophila axons in vivo. These findings suggest modulation of the subcellular localisation of Nmnat2 as a novel means of extending axon survival in ageing and disease.

Results

Expression of Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus in transgenic mice

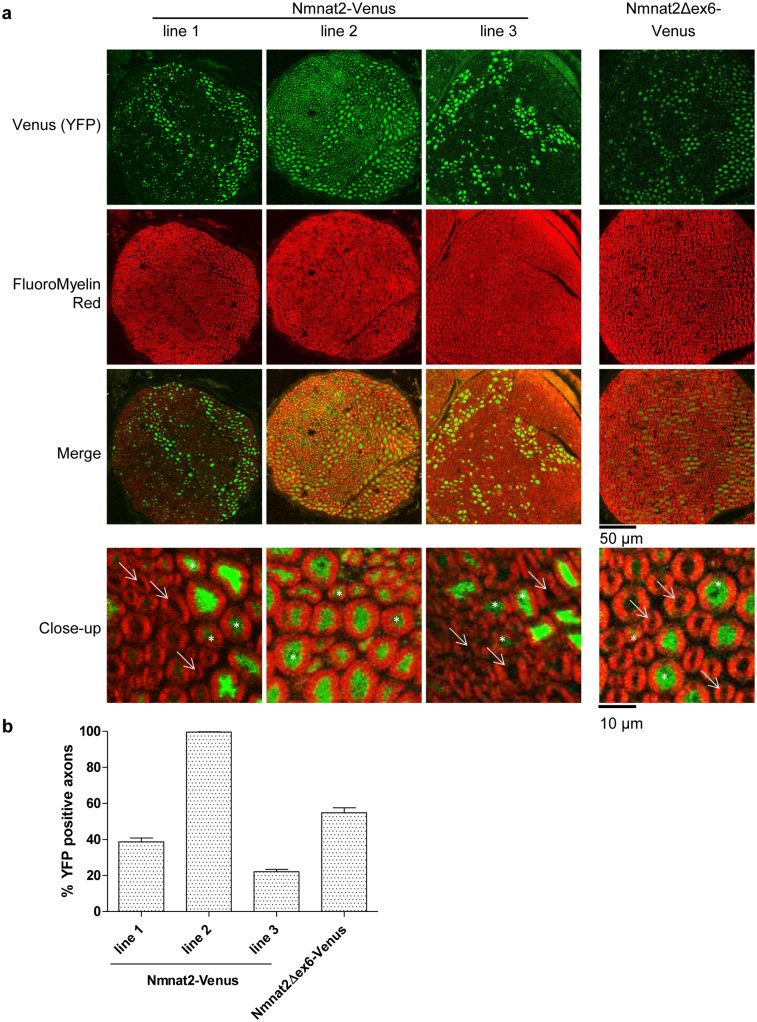

In order to study the role of exon 6 – encoded sequences (which we refer to as the “central ISTID region”) in regulating Nmnat2 localisation and turnover in vivo, we generated two strains of transgenic mice. Nmnat2-Venus mice (lines 1, 2 and 3 used in this study) express full-length, wild-type Nmnat2 fused to YFP Venus while Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice express Nmnat2 deficient of exon 6-encoded central ISTID sequences (see Supplementary Figure 1 for an outline of relevant Nmnat2 regions and the position of the exon 6 deletion). Expression in both strains is driven by the Thy1.2 neuron-specific promoter18. The presence of the transgene was confirmed by PCR from genomic DNA (Supplementary Figure 2a) and expression of the fusion protein was detectable by Western Blot in total brain as well as in sciatic nerve (Supplementary Figure 2b). Total expression levels in sciatic nerve vary between lines, with line 1 in particular showing notably higher total expression levels than the other Nmnat2-Venus lines, and than Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice. However, in interpreting this observation, one has to consider the reported finding that Thy1.2-driven transgene expression does not necessarily occur in all neurons and that expression patterns vary widely between lines18,19,20. For this reason, we quantified the percentage of axons expressing the transgene in sciatic nerves from all lines. Cryo-sections of sciatic nerves were stained with FluoroMyelin Red dye and the number of axons exhibiting detectable above-background levels of YFP fluorescence quantified as a percentage of total axons (identified by myelin staining, see Methods for details). As expected, we found considerable differences between lines (Figure 1). In particular, Nmnat2-Venus line 2 showed detectable expression in virtually all axons while expression in other lines was detectable in around 20–50% of axons. Figure 1a also illustrates that expression levels (as judged by YFP intensity) vary between individual axons within the same nerve. Thus we cannot rule out the possibility that some axons might express very low levels of the transgene below our detection threshold. The transgene was inherited with the expected ratios in all transgenic lines and no overt phenotypic abnormalities were observed up to at least 12 months of age, suggesting that expression of Nmnat2-Venus or Nmnat2Δex6-Venus does not have obvious adverse effects.

Figure 1. Characterisation of transgene expression in Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mouse lines.

(a) Cryostat cross-sections (20 μm thickness) of sciatic nerves of Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice. YFP fluorescence from transgene expression is shown in green and FluoroMyelin staining is shown in red. In close-up images, white arrows indicate axons that were scored negative for transgene expression and white asterisks indicate axons that were scored positive (note that in line 2 images, virtually no axons were found to be negative for transgene expression). (b) Quantification of the percentage of total axons (identified by FluoroMyelin staining) that showed detectable (above-background) YFP expression in Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mouse sciatic nerves (see Methods). Error bars indicate SEM.

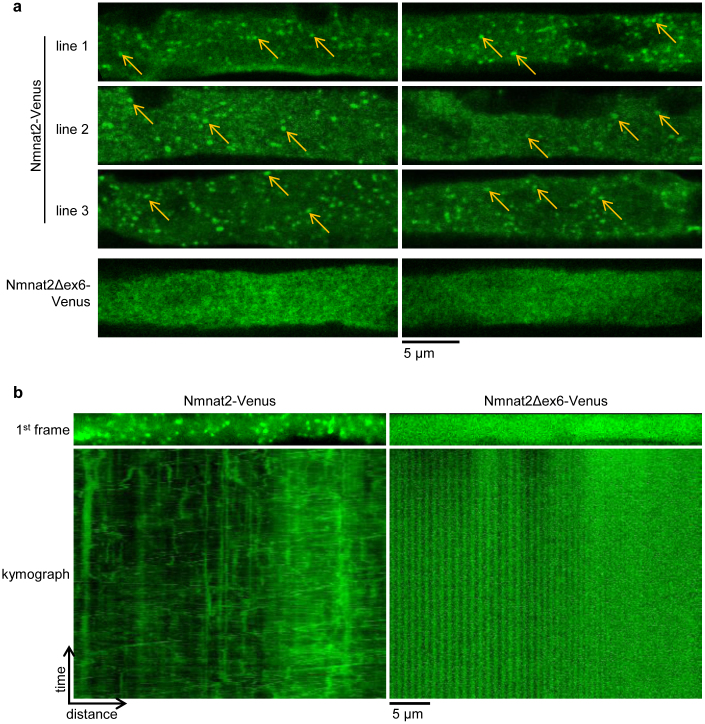

The central ISTID region is necessary for vesicle association in vivo

In primary culture neurons, Nmnat2 associates with Golgi-derived transport vesicles and undergoes fast axonal transport. Loss of the palmitoylation site in its central ISTID region is sufficient to disrupt transport vesicle association and causes Nmnat2 to assume a diffuse, cytosolic distribution9. In order to test whether Nmnat2 assumes a vesicular localisation in vivo, and whether the central ISTID region is necessary for this, we analysed whole-mount sciatic nerves of Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice. As shown in Figure 2a, clearly identifiable vesicles were observed in sciatic nerve axons from all Nmnat2-Venus lines. In contrast, only diffuse, cytosolic staining was observed in Nmnat2Δex6-Venus axons with no evidence of vesicular association in any of the axons analyzed. Additionally, we confirmed that Nmnat2-Venus vesicles were mobile in peripheral axons through live-imaging of sciatic nerve explants. We observed abundant, bidirectional movement of vesicles in Nmnat2-Venus axons. In contrast, no vesicular structures or movement were observed in Nmnat2Δex6-Venus axons (Figure 2b and Supplementary Movie 1). These results are consistent with a vesicular localisation of Nmnat2-Venus in vivo that is dependent on the central ISTID region.

Figure 2. The central ISTID region is necessary for vesicle association of Nmnat2-Venus in vivo.

(a) Single longitudinal confocal slices of whole-mounted sciatic nerve axons showing numerous clearly identifiable vesicles in nerves from Nmnat2-Venus mice (some highlighted by arrows in each image) compared to exclusively diffuse, cytosolic staining in nerves from Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice. Two representative images are shown for each line. (b) First frame and corresponding kymograph (time-distance graph) of representative sciatic nerve axon live imaging time series from Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice. Total time represented in kymograph is 2 minutes (240 frames at 2 fps).

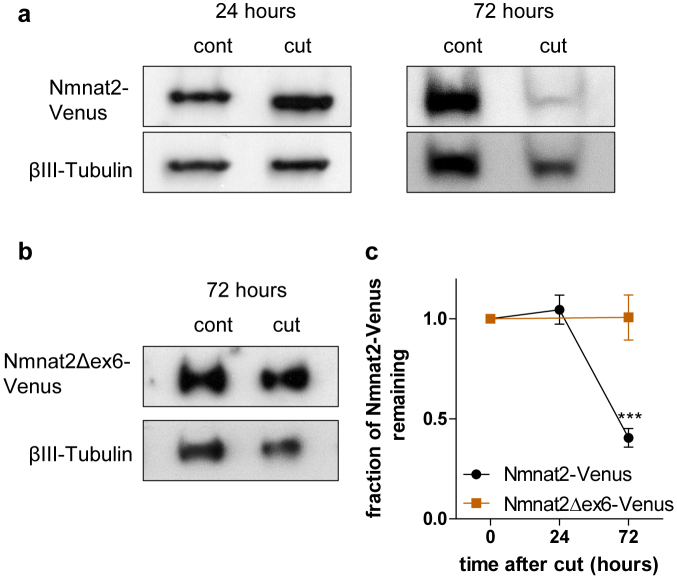

Loss of the central ISTID region prolongs Nmnat2 half-life in vivo

We previously described emetine chase experiments in HEK 293 cells showing that loss of exon 6-encoded sequences prolonged Nmnat2 half-life considerably9. Due to the low level of expression of endogenous Nmnat2 in axons, the limited quality of available antibodies12 and the potentially compounding issue of expression in non-neuronal cells, the in vivo turnover of endogenous Nmnat2 in axons is difficult to study. We therefore used the neuron-specific expression of Nmnat2-Venus in our transgenic mice to test whether loss of the central ISTID region delays Nmnat2 turnover in mouse peripheral nerves. For this, we performed unilateral sciatic nerve lesions and collected sciatic nerves 24 or 72 hours after injury (as shown in Figure 4 and discussed below, Wallerian degeneration does not occur at these time points in axons expressing the transgene in Nmnat2-Venus or Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice). For quantification, we normalised Nmnat2-Venus levels to βIII-Tubulin levels. For Nmnat2-Venus, the relative level was unchanged 24 hours after cut, but we observed a substantial drop at 72 hours after cut (Figure 3a, c). In contrast, there was essentially no change in Nmnat2Δex6-Venus levels relative to βIII-Tubulin at 72 hours after cut (Figure 3b, c). This suggests that loss of the central ISTID region stabilises Nmnat2-Venus in vivo. It is important to note, however, that the observed rate of turnover for wild-type Nmnat2-Venus is considerably slower than that reported for endogenous Nmnat2 in primary culture neurites1, as well as for FLAG-tagged Nmnat2 in HEK 293 cells9. This is most likely attributable to the YFP tag in the transgenic mice as we found Nmnat2-EGFP to be considerably more stable than FLAG-Nmnat2 in HEK 293 cells (Supplementary Figure 3). Thus, whilst the rate of turnover we observed for Nmnat2-Venus probably does not reflect the true half-life of untagged, wild-type Nmnat2, the fact that Nmnat2Δex6-Venus is considerably more stable than Nmnat2-Venus in cut sciatic nerve nevertheless strongly supports a role for the central ISTID region in tuning Nmnat2 turnover in vivo.

Figure 3. Loss of the central ISTID region stabilises Nmnat2-Venus in vivo.

(a) Representative Western Blots (cropped) of Nmnat2-Venus expression in sciatic nerves from Nmnat2-Venus line 2 animals 24 or 72 hours after axotomy compared to contralateral, uncut nerve from the same animal. Nmnat2-Venus was detected by the YFP tag. βIII-Tubulin was used as loading control. (b) Representative Western Blot (cropped) of Nmnat2Δex6-Venus expression (detected by YFP tag) in sciatic nerve 72 hours after axotomy compared to contralateral, uncut nerve from the same animal. βIII-Tubulin was used as loading control. (c) Quantification of Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus turnover in cut sciatic nerve. Expression of Nmnat2-Venus (or Nmnat2Δex6-Venus) was normalised to βIII-Tubulin levels in the same nerve. For presentation purposes, expression levels at 24 and 72 hours after axotomy were normalised to uncut nerve. Error bars indicate SEM. *** indicates statistically significant difference compared to Nmnat2-Venus (p < 0.001, n = 3–4 nerves per line).

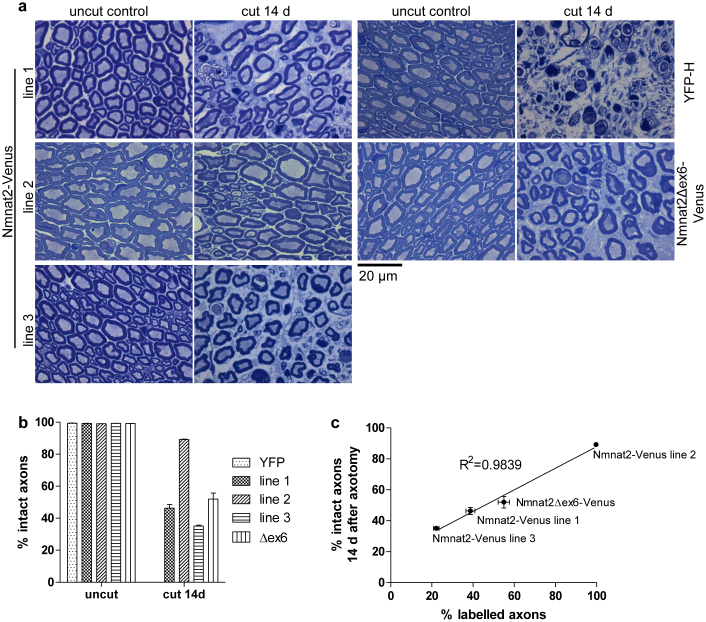

Figure 4. Strong axon protection by Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus after sciatic nerve axotomy.

(a) Representative images of Richardson stained semi-thin (500 nm) sections of 14-day cut or uncut sciatic nerves of YFP-H, Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice. (b) Quantification of percentage intact axons in uncut and 14-day cut sciatic nerves from YFP-H (YFP), Nmnat2-Venus (line 1, 2 and 3) and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus (Δex6) mice. Error bars indicate SEM. (c) Graph showing correlation between percentage of axons identified as labelled in sciatic nerve cryo-sections and percentage of axons preserved in sciatic nerves of the same animals 14 days post-axotomy. Line represents best-fit linear regression, error bars show SEM. The relevant transgenic line is indicated for each data point.

Overexpressed, stabilised Nmnat2 delays Wallerian degeneration in vivo

We next reasoned that the relative overexpression of Nmnat2-Venus, together with its likely stabilisation compared to wild-type Nmnat2, should delay the course of Wallerian degeneration in Nmnat2-Venus transgenic mice. Using sciatic nerve lesion experiments, we quantified the percentage of axons that appeared morphologically intact 14 days after injury. In wild-type animals, degeneration starts at 36 hours after cut and is mostly complete by 72 hours17. Accordingly, 14 days after cut, axons expressing YFP only (from YFP-H animals) were completely degenerated (Figure 4a, b). In contrast, Nmnat2-Venus animals showed a significant portion of intact axons at this time point. The degree of protection varied between lines, with the largest percentage of intact axons observed in line 2, but all lines analyzed showed a considerable degree of protection (Figure 4a, b). The difference in protective capacity between lines most likely reflects the difference in expression pattern (see Figure 1) as we observed a very strong correlation between the percentage of YFP-positive axons and the percentage of axons protected at 14 days after cut (R2 = 0.9839, Figure 4c). These results indicate that overexpression of the relatively stable Nmnat2-Venus fusion protein in peripheral axons is sufficient to afford a significant delay in the time course of Wallerian degeneration. In previously described in vitro experiments we found that loss of exon 6-encoded sequences dramatically enhanced the ability of Nmnat2 to delay neurite degeneration after cut when expressed at low levels in primary culture neurons9. In order to test whether loss of this central ISTID region would also increase the protective capacity of Nmnat2 in vivo, we compared the ability of Nmnat2Δex6-Venus to delay axon degeneration after sciatic nerve injury in mice to that of Nmnat2-Venus. As for the Nmnat2-Venus lines above, we found substantial protection of Nmnat2Δex6-Venus axons at 14 days after sciatic nerve injury (Figure 4a, b), especially when taking into account the percentage of labelled axons observed (Figures 1 and 4c). As illustrated in Figure 4c, in wild-type Nmnat2-Venus mice, the fraction of axons that express detectable levels of Nmnat2-Venus and the fraction of axons that were morphologically intact 14 days after cut are nearly identical. This suggests very strong protection by wild-type Nmnat2 when stabilised by fusion to YFP Venus. Thus, there was virtually no scope for Nmnat2Δex6-Venus to provide stronger protection than wild-type Nmnat2-Venus in this case. Accordingly, we observed a similar maximal protective capacity of Nmnat2Δex6-Venus compared to wild-type Nmnat2-Venus (Figure 4).This means that the existing Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mouse lines did not allow us to adequately test the hypothesis that loss of the central ISTID region boosts the axon protective capacity of Nmnat2 in vivo.

Loss of ISTID regions enhances protective capacity of Nmnat2 in Drosophila axons

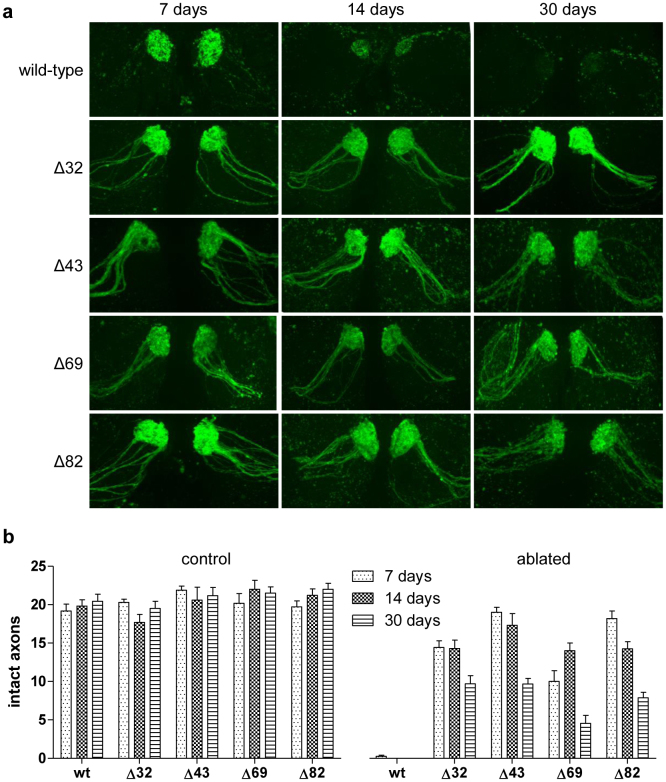

In order to clarify whether loss of central ISTID regions can improve axon protection by Nmnat2 in vivo, we tested the protective capacities of wild-type and mutant Nmnat2 isoforms, lacking any tags that could stabilise the protein, in Drosophila axons. We previously found that a series of deletion mutants (Nmnat2Δ32, Δ43, Δ69 and Δ82 – see Supplementary Figure 1 for an outline of the location of the deletion in each mutant) based on human Nmnat221 have greatly increased axon protective capacity compared to wild-type Nmnat2 in mouse primary culture neurites9. The deletions in these mutants span parts of the central isoform-specific targeting and interaction domain (ISTID)13 region of Nmnat2 and include part (Δ32) or all of the exon 6 – encoded region (Δ43, Δ69 and Δ82), which is essential for targeting Nmnat2 to vesicles9. We expressed wild-type and each of these mutant Nmnat2 isoforms in flies in which a subset of antennal olfactory receptor neuron (ORN) axons were labelled by GFP expression (OR22a-Gal4, UAS-mCD8::GFP)22,23. Axotomy was induced by bilateral third antennal segment ablation and the number of remaining GFP-positive axons was scored 7, 14 and 30 days after axotomy. We previously found non-stabilised wild-type Nmnat2 to be only weakly protective and to require strong overexpression in order to achieve moderate protection in mouse primary culture neurites1,9. Consistent with this and with other previous work24, we found that expression of untagged human Nmnat2 in Drosophila did not preserve ORN axons at any of the time points analysed (Figure 5). In contrast, flies expressing the deletion mutants showed strong preservation of ablated axons 7 and 14 days after axotomy, with a substantial proportion being protected until 30 days after antennal ablation (Figure 5). These findings support a role for the central ISTID region in modulating Nmnat2 axon protective capacity in vivo. Moreover, these data also suggest that the molecular mechanisms by which loss of the central ISTID region boosts Nmnat2 axon protective capacity are conserved from Drosophila to mammals.

Figure 5. Nmnat2 deletion mutants with strongly increased protective capacity in Drosophila axons.

(a) Representative images of GFP-positive (OR22a+) axons in antennal lobes of flies expressing wild-type or mutant human Nmnat2 (wt – full-length Nmnat2, Δ32 – Nmnat2Δ32, Δ43 – Nmnat2Δ43, Δ69 – Nmnat2Δ69, Δ82 – Nmnat2Δ82). Images were taken 7, 14 and 30 days after bilateral antennal ablation as indicated. (b) Quantification of number of intact GFP-expressing axons in antennal lobe of flies expressing wild-type or mutant Nmnat2 isoforms scored 7, 14 and 30 days post-ablation. Age-matched untreated flies were used as controls. Error bars indicate SEM. n ≥ 3 antennal lobes per genotype and time point.

Discussion

We previously reported that loss of exon 6-encoded sequences boosts the protein stability and axon protective capacity of Nmnat2 in vitro9. The results presented here confirm that a similar mechanism operates in vivo. We find that deletion of the central, exon 6-encoded ISTID region causes loss of vesicle association and delays the turnover of Nmnat2-Venus in mouse peripheral axons. Moreover, untagged mammalian Nmnat2, which is not protective in Drosophila ORN axons24 and provided only weak, transient protection in Drosophila wing axons25, can be transformed into a highly protective protein for Drosophila axons through deletions of its central ISTID region. These findings are an important confirmation illustrating the possibility of turning endogenous Nmnat2 into a highly protective molecule to address axon degeneration in a mammalian system.

The strong protective effect observed with Nmnat2-Venus alone meant that our mouse lines did not allow us to directly compare the protective capacities of wild-type and central ISTID – deficient Nmnat2 in vivo. While it is possible that loss of the central ISTID region does not improve Nmnat2 – mediated axon protection in mouse peripheral axons, it appears more likely that the strong overexpression and enhanced stability of Nmnat2-Venus relative to endogenous Nmnat2 masks any potential benefit of the deletion of the central ISTID. Due to the high steady-state level and longer half-life relative to endogenous Nmnat2, levels of Nmnat2-Venus remain above the threshold required for axon maintenance, even when its relative levels drop between 24 and 72 hours after cut. This interpretation is further supported by the observed effect of deletion of the central ISTID region on the stability of Nmnat2-Venus, which would likely translate into a higher protective capacity under conditions of lower expression. Finally, the strong increase in protective capacity of mammalian Nmnat2 ISTID deletion mutants in Drosophila olfactory receptor neuron axons further supports a role for the central ISTID region in tuning Nmnat2-mediated axon protection.

Even though Drosophila has only a single Nmnat isoform, our results suggest that the ISTID–dependent destabilisation or mislocalisation mechanism observed for mammalian Nmnat2 is conserved across species. Mammalian Nmnat2 was previously shown to be able to substitute for dNmnat to some extent in Drosophila25. Additionally, Highwire, an E3 ubiquitin ligase proposed to regulate turnover and protective capacity of dNmnat, also affects the stability of mammalian Nmnat2 in Drosophila axons11. Here we find that protection of Drosophila ORN axons by mammalian Nmnat2 is boosted by loss of central ISTID regions, which stabilises Nmnat2 in mammalian nerves and greatly enhances axon protection in mammalian primary culture neurons. These results indicate that the mechanisms that mediate the delayed degeneration resulting from deletion of Nmnat2 central ISTID sequences in mammalian primary culture axons are conserved in Drosophila.

Confirming our primary culture observations, loss of the central ISTID region does not interfere with the entry of Nmnat2-Venus into long peripheral axons. While we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the YFP tag somehow mediates axon entry, this suggests that long-range vesicle-mediated transport might not be necessary to deliver Nmnat2 into axons, even in vivo. Other soluble proteins have been reported to be trafficked into axons by transient attachment to the transport machinery26. This of course raises the question as to the functional role of Nmnat2 vesicle association in axons. One possibility, consistent with our results, is that vesicle-association helps to ensure rapid removal and turnover of Nmnat2. However, given the absence of adverse effects observed in any of our transgenic lines overexpressing a stabilised, mislocalised form of the protein, the importance of Nmnat2 instability to the normal functioning of axons is presently unclear. It is, however, important to note that expression of Nmnat2-Venus in these mice does not commence until the post-natal period, masking any potential effects of a stabilised Nmnat2 on developmental processes. Additionally, rapid removal of Nmnat2 after an injury will of course facilitate rapid de- and re-generation of axons, allowing quick functional recovery, which remains to be tested in our Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice.

In summary, our results support a role for the central ISTID region in tuning Nmnat2 localisation, stability and protective capacity in vivo. Loss of the central ISTID region transforms Nmnat2 from an unstable, vesicle-associated protein that is nevertheless critical for preventing spontaneous degeneration of unharmed axons, into a widely distributed, stabilised protein that can robustly protect axons after injury. Understanding the mechanisms behind this phenomenon could uncover novel avenues for axon protection through modulation of endogenous Nmnat2.

Methods

Mouse strains

All animal work was carried out in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, under Project License 80/2254. C57BL/6JBabr mice (BSU, Babraham Institute) were used for breeding. YFP-H mice (exact strain name: B6.Cg-TgN(Thy1-YFP-H)2Jrs) used as controls were heterozygotes.

Generation of transgenic mice

Transgene expression in Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus was driven by the Thy1.2-promoter that has previously been described for the generation of neuron-specific transgenic mouse lines18,19,20. The coding sequences of full-length mus musculus Nmnat2 or the Nmnat2Δex6 deletion mutant9 were C-terminally fused to YFP Venus27 (kindly provided by Dr. Llewelyn Roderick, Babraham Institute) and inserted into the Thy1.2 expression vector (a kind gift from Prof. Thomas Misgeld, TU Munich). Transgenic mice were generated by pronuclear injection (Babraham Institute Gene Targeting Facility) into C57BL6/CBA F1 zygotes. For Nmnat2-Venus mice, nine potential founders were identified and four transgenic lines (1, 2, 3 and 8) were maintained as heterozygotes by crossing to C57BL/6JBabr. Lines 1, 2 and 3 were used for experiments described in this study. For Nmnat2Δex6-Venus, a single founder was identified and one transgenic line was established, maintained by crossing to C57BL/6JBabr and used for this study.

PCR genotyping

PCR primers were designed to amplify a region of Nmnat2 from the start of exon 9 to the end of exon 10 (fwd: 5′-atggaagtgattgttggggac-3′; rev: 5′-ctgctcttggtggagctgac-3′). This resulted in a 300 bp fragment for endogenous Nmnat2 and a 170 bp fragment indicating the presence of Nmnat2-Venus or Nmnat2Δex6-Venus as these constructs lack the intervening intron.

Collection of brains and nerves for western blot analysis

Brain and sciatic nerves were dissected rapidly from freshly killed mice and frozen immediately by immersion in liquid nitrogen. For lysis, tissue was allowed to thaw on ice and 500 μl (for brain halves) or 50 μl (for sciatic nerve) TG lysis buffer was added (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1% TritonX-100, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitor mix). Tissue was disrupted by sonication for 3 times 6 seconds on ice. Unbroken cells were removed by spinning samples at 13 000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C and transferring the supernatant to a new tube. Sciatic nerve samples were diluted 1:1 and brain samples 1:4 into 2× SDS sample buffer prior to SDS PAGE and Western Blot analysis.

Western blotting

SDS-PAGE analysis and Western Blotting analysis were performed as described1,28. Anti-GFP antibody (Abcam ab290) was used at 1:2000, anti-βIII-Tubulin (TUJ1, Covance) was used at 1:15 000 and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (BioRad) were used at 1:2000.

Tissue cryo-sectioning and staining

Nerves from freshly killed animals were dissected rapidly and fixed by immersion into cold 4% PFA for at least 3 days, washed 3 times in 0.1 M PBS and cryopreserved in 30% sucrose supplemented with 0.1% sodium azide for at least 3 days at 4°C. Tissue was sectioned on a Leica CM1850 cryostat. Typical section thickness was 20 μm for nerve cross-sections. Sections were transferred onto Superfrost plus slides (VWR), allowed to dry and permeabilised in PBS with 0.2% Triton-X 100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Where indicated, sections where then stained with FluoroMyelin Red stain according to manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies). Stained sections were imaged on an Olympus FV1000 point scanning confocal microscope (IX81 microscope, 60 × 1.35 NA plan super apochromat and 40× plan fluorite 1.3 NA objectives). For quantification of the percentage of axons expressing the transgene, the total number of axons in a field was determined by counting FluoroMyelin – stained myelin rings. Axons were scored as positive for transgene expression if above-background levels of YFP fluorescence were detectable in the axoplasm (see Figure 1a for examples of axons scored as positive and negative for transgene expression). Six representative fields of view, each of which contained about 100 axons, were counted and averaged per animal for a total of n = 4 animals per line.

Nerve whole-mount

For longitudinal sciatic nerve whole-mount preparations, freshly dissected sciatic nerves were gently stretched during fixation using insect pins. Nerves were fixed in 4% PFA for at least 2 days at 4°C. Fixed nerves were then washed three times in 0.1 M PBS, transferred to a slide and a coverslip was mounted using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

Semi-thin sectioning and staining

Sciatic nerves were fixed, embedded and sectioned to 500 nm thickness as previously described29 and stained using Richardson's stain (0.5% Methylene Blue, 0.5% Azure II in 0.5% sodium tetraborate). Stained sections were visualised on a brightfield microscope equipped with a colour camera (Olympus BX41/Micropublisher 3.3 system, 100 × 1.4 NA objective).

Axonal transport imaging of sciatic nerve explants

Imaging of axonal transport in sciatic nerve explants of Nmnat2-Venus and Nmnat2Δex6-Venus mice was performed on an Olympus CellR imaging system (IX81 microscope, Hamamatsu ORCA ER camera, 100 × 1.45 NA apochromat objective). During imaging, nerves were maintained in oxygenated Neurobasal-A medium at 37°C in an environment chamber (Solent Scientific). Images were captured at 2 frames per second. Following imaging, individual axons were straightened and kymographs generated using ImageJ software plugins (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2013).

Construction of Nmnat2 vectors and transgenic flies

Nmnat2 deletion mutants (Δ32, Δ43, Δ69, and Δ82)21 were a gift from Prof. Giulio Magni (Ancona, Italy). The ORF of human Nmnat2 (wild-type or deletion mutant) was amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′-AGTCAAGATCTACCCCACTGACCGAGACCACCAAGACC-3′ (5′ primer with Kozak sequence and 5′ BglII site) and 5′-GGATCTCGAGCTAGCCGGAGGCATTGATGTACAGC-3′ (3′ primer with XhoI site), cloned into a modified pJFRC-MUH plasmid (Addgene plasmid 26213; modified by cutting pJFRC-MUH with SbfI and SphI, removing 128 bp, including one 5× UAS site), and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Drosophila embryo injections were performed as a fee-for-service (BestGene, Inc., Chino Hills, CA) and transgenic lines established in the attP40 strain (estimated cytosite 25C7) were confirmed for the presence of the wild-type or mutant transgene by sequencing of PCR product.

Antennal injury and axon quantification

OR22a-Gal422 and pUAST-mCD8::GFP were combined with each Nmnat2 construct. We induced antennal injury using a modification of a previously described protocol23. Newly eclosed adult flies were aged for 7 days at 25°C before ablating both third antennal segments (bilateral injury). Injured flies were aged at 25°C for the indicated time (7, 14, or 30 days) before dissecting and fixing the brain. Axonal integrity was scored by counting the number of intact GFP positive axons present.

Drosophila confocal microscopy

Samples were mounted in Vectashield antifade reagent and viewed on a III Everest Spinning disk confocal microscope (40×, 1.3 NA, Plan Apochromat objective). The entire antennal lobe was imaged in 0.27 μm steps for each sample for scoring axonal integrity.

Statistical analysis

Data presentation and statistical analysis were performed with Prism 5 (GraphPad) and SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM) software.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: S.M., A.N.F., M.R.F., M.P.C. Performed the experiments: S.M., A.N.F. Analysed the data: S.M., A.N.F. Prepared the figures: S.M. Wrote the paper: S.M., A.N.F., M.R.F., M.P.C.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Movie 1

Acknowledgments

We would like thank Robert Adalbert for helpful discussion, Jon Gilley for valuable comments on the manuscript, Simon Walker for assistance with live imaging and Llewelyn Roderick, Giulio Magni and Thomas Misgeld for donation of plasmid constructs.

Financial disclosure: This work was funded by a Medical Research Council (MRC; http:// www.mrc.ac.uk) studentship (SM), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (http://www.bbsrc.ac.uk) Institute Strategic Programme Grant (MPC) and NIH RO1 NS059991 (MRF).MRF is an Early Career Scientist with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Gilley J. & Coleman M. P. Endogenous Nmnat2 Is an Essential Survival Factor for Maintenance of Healthy Axons. PLoS Biol 8, e1000300 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J., Adalbert R., Yu G. & Coleman M. P. Rescue of Peripheral and CNS Axon Defects in Mice Lacking NMNAT2. J Neurosci 33, 13410–13424 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack T. G. et al. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat Neurosci 4, 1199–206 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babetto E. et al. Targeting NMNAT1 to axons and synapses transforms its neuroprotective potency in vivo. J Neurosci 30, 13291–304 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y., Vohra B. P. S., Baloh R. H. & Milbrandt J. Transgenic mice expressing the Nmnat1 protein manifest robust delay in axonal degeneration in vivo. J Neurosci 29, 6526–34 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Overexpression of Wld(S) or Nmnat2 in mauthner cells by single-cell electroporation delays axon degeneration in live zebrafish. J Neurosci Res 88, 3319–27 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan T. et al. Nmnat2 delays axon degeneration in superior cervical ganglia dependent on its NAD synthesis activity. Neurochem Int 56, 1–6 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungberg M. C. et al. CREB-activity and nmnat2 transcription are down-regulated prior to neurodegeneration, while NMNAT2 over-expression is neuroprotective, in a mouse model of human tauopathy. Hum Mol Genet 21, 251–67 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde S., Gilley J. & Coleman M. P. Subcellular Localization Determines the Stability and Axon Protective Capacity of Axon Survival Factor Nmnat2. PLoS Biol 11, e1001539 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Q. et al. Involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the early stages of wallerian degeneration. Neuron 39, 217–25 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X. et al. The Highwire Ubiquitin Ligase Promotes Axonal Degeneration by Tuning Levels of Nmnat Protein. PLoS Biol 10, e1001440 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babetto E., Beirowski B., Russler E. V., Milbrandt J. & DiAntonio A. The Phr1 ubiquitin ligase promotes injury-induced axon self-destruction. Cell Rep 3, 1422–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C. et al. Isoform-specific targeting and interaction domains (ISTIDs) in human nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNATs). J Biol Chem 3, 18868–18876 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T., Sasaki Y. & Milbrandt J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. Science 305, 1010–3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L. et al. NAD(+) and axon degeneration revisited: Nmnat1 cannot substitute for Wld(S) to delay Wallerian degeneration. Cell Death Differ 14, 116–27 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahata N., Yuasa S. & Araki T. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase expression in mitochondrial matrix delays Wallerian degeneration. J Neurosci 29, 6276–84 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirowski B. et al. The progressive nature of Wallerian degeneration in wild-type and slow Wallerian degeneration (WldS) nerves. BMC Neurosci 6, 6 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P. Overexpression of growth-associated proteins in the neurons of adult transgenic mice. J Neurosci Methods 71, 3–9 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld T., Kerschensteiner M., Bareyre F. M., Burgess R. W. & Lichtman J. W. Imaging axonal transport of mitochondria in vivo. Nat Methods 4, 559–61 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G. et al. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 28, 41–51 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti L., Di Stefano M., Ruggieri S., Cimadamore F. & Magni G. Homology modeling and deletion mutants of human nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase isozyme 2: new insights on structure and function relationship. Protein Sci 19, 2440–50 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritsa A. A., Van der Goes van Naters W., Warr C. G., Steinbrecht R. A. & Carlson J. R. Integrating the molecular and cellular basis of odor coding in the Drosophila antenna. Neuron 37, 827–41 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J. M. et al. The Drosophila cell corpse engulfment receptor Draper mediates glial clearance of severed axons. Neuron 50, 869–81 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery M. A., Sheehan A. E., Kerr K. S., Wang J. & Freeman M. R. Wld S requires Nmnat1 enzymatic activity and N16-VCP interactions to suppress Wallerian degeneration. J Cell Biol 184, 501–13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Soares L., Teng X., Geary M. & Bonini N. M. A Novel Drosophila Model of Nerve Injury Reveals an Essential Role of Nmnat in Maintaining Axonal Integrity. Curr Biol 22, 590–595 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. A., Das U., Tang Y. & Roy S. Mechanistic logic underlying the axonal transport of cytosolic proteins. Neuron 70, 441–54 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T. et al. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol 20, 87–90 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J. et al. Age-dependent axonal transport and locomotor changes and tau hypophosphorylation in a “P301L” tau knockin mouse. Neurobiol Aging 33, 621.e1–621.e15 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adalbert R. et al. A rat model of slow Wallerian degeneration (WldS) with improved preservation of neuromuscular synapses. Eur J Neurosci 21, 271–7 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Movie 1