Abstract

Background:

Cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones is mainly performed after the acute cholecystitis episode settles because of the fear of higher morbidity and conversion from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open cholecystectomy during acute cholecystitis.

Aims:

To evaluate the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis and to compare the results with delayed cholecystectomy.

Materials and Methods:

This was a prospective and randomized study. For patients assigned to early group, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed as soon as possible within 72 hours of admission. Patients in the delayed group were treated conservatively and discharged as soon as the acute attack subsided. They were subsequently readmitted for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy 6-12 weeks later.

Results:

There was no significant difference in the conversion rates, postoperative analgesia requirements, or postoperative complications. However, the early group had significantly more blood loss, more operating time, and shorter hospital stay.

Conclusion:

Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours of onset of symptoms has both medical as well as socioeconomic benefits and should be the preferred approach for patients managed by surgeons with adequate experience in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Acute cholecystitis, Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic

Introduction

Biliary diseases constitute a major portion of digestive tract disorders. Among these is cholelithiasis, which causes general ill health, and hence requires surgical intervention for total cure.[1] Gallstone disease is three times more common in women than men. With advancing age, prevalence increases from 4% in the third decade of life to 27% in the seventh decade of life.[2] Acute cholecystitis is a major complication of gallstones. In the past several decades, research has been conducted along several avenues to develop less invasive, less painful, and less expensive methods of gallstone treatment. Such methods like oral desaturation agents, contact dissolution agents, and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, are limited by stone content, size, and number. In addition, they leave an intact gallbladder already known to harbor lithogenic bile. Thus, these nonoperative methods are inadequate for a large proportion of gallstone patients and cannot promise a permanent cure from gallstone disease.[3] Hence, cholecystectomy remains the treatment of choice for gallstone disease. Open cholecystectomy remains the gold standard for symptomatic cholelithiasis for over a century. However, in the last decade, the introduction of laparoscopic technique to perform cholecystectomy has revolutionized this procedure.[4]

The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 1985 by Muhe, and a report was presented in the German surgical society in 1986. The surgery was later performed by Mouret in 1987 and by Dubois in May 1988 in France. However, Reddick and Oslen devised the currently used method for laparoscopic cholecystectomy while performing their first case in September 1988.[3,5] Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was thus performed as an elective procedure and achieves the goal of shorter recovery time, decreased expense, less postoperative pain, and improved cosmesis.[5] In the early years of minimally invasive surgery, acute cholecystitis was considered to be a relative contraindication to laparoscopic cholecystectomy because of inflammatory changes making dissection difficult and because of friability of tissues and ill-defined surgical planes. As laparoscopy became the gold standard treatment for chronic cholecystitis with cholelithiasis, and the surgeons excelled in performing the surgery, even acute cases were considered for laparoscopy. The acute inflammation associated with acute cholecystitis creates an edematous plane on liver bed. The edema may spread into the triangle of Calot or it may stop at the fundus of gall bladder, leaving Calot’s triangle reasonably free of inflammation. When acute inflammation matures to chronic inflammation, neovascularity, fibrosis, and contraction makes laparoscopic cholecystectomy substantially more difficult and potentially more dangerous. As a general rule, with patients who have acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed as soon as convenient, within the first 72 hours. There is no benefit in attempting to ‘cool off’ the gallbladder before proceeding to the operating room. Laparoscope or no laparoscope, the message remains the same: For acute cholecystitis, get it while it is hot.[2]

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis has still not become routine because the timing and approach to the surgical management in patients with acute cholecystitis is still a matter of controversy.[6] Several studies have concluded that cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis should be carried out during 72 hours of admission,[7,8] with an advantage to decrease the morbidity and mortality of patients due to complications who would otherwise need repeated admissions for recurrent symptoms.

This prospective randomized study was undertaken to evaluate the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis and compare the results with those of delayed cholecystectomy. Comparison following early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy was done in terms of safety of the procedure, operating time, blood loss and requirement of transfusion, injury to organs – bile ducts, bowel, liver, postoperative pain, hospital stay, resumption of orals, cosmetic comparisons (patient satisfaction and scar), cost factor, and loss of active days of work (days away from the work).

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective and comparative study, conducted in the Department of Surgery, Government Medical College, Srinagar, from July 2008 to July 2011. The study was approved by local ethics committee.

The study comprised 60 cases (30 in each group). Before the procedure, fully informed consent was taken. Patients were fully informed that the gallbladder and stones will be removed. Additionally, patients’ consent for conversion to an open procedure was obtained.

All patients were subjected to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patients were admitted with a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis and randomly assigned to receive either early laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours of admission (early group, n = 30) or initial conservative treatment followed by delayed interval surgery 6-12 weeks later (delayed group, n = 30), by a computer-generated random number list kept by a third party.

The diagnosis of acute cholecystitis was based on the finding of acute upper abdominal pain, with acute right upper quadrant tenderness for more than 6 hours, associated nausea or vomiting, fever (>100°F), and ultrasonographic (USG) evidence of acute cholecystitis such as distended gall bladder, presence of gallstones with a thickened and edematous gallbladder wall, positive Murphy's sign, and pericholecystic fluid collections. In addition, increased total leukocyte count (>10,000/mm3) in such patients was taken as an inclusive criterion for acute cholecystitis.

The initial supportive treatment during the acute phase was same for both groups of patients. All patients received intravenous (i.v.) fluid infusion and i.v. antibiotics. For patients assigned to early group, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed as soon as possible within 72 hours by a consultant general surgeon having extensive experience in laparoscopic surgery. Patients in the delayed group were treated conservatively and discharged as soon as the acute attack subsided. They were subsequently readmitted for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy 6-12 weeks later.

Patients excluded from the study were those with symptoms for more than 72 hours before surgery, patients with surgical jaundice (bilirubin level above 3.5 mg/dl), USG-proved choledocholilithiasis, malignancy, preoperatively diagnosed acute gallstone-induced pancreatitis, previous upper abdominal surgery, significant medical disease rendering them unfit for laparoscopic surgery, and those who refused to undergo laparoscopic surgery.

On admission, a detailed history was taken. Thorough general physical examination and systemic examination was done for every patient. Relevant investigations were done, which included complete hemogram, urine examination, blood urea, serum creatinine, blood sugar, serum electrolytes, liver function test, serum amylase, and lipase where indicated, besides X-ray chest, electrocardiogram, and USG abdomen.

The patients were administered general anesthesia and placed in supine position on the operating table. Nasogastric tube was inserted to decompress the stomach. Pneumoperitoneum was created by a blind puncture with a Veress needle through a supraumbilical incision. Four laparoscopic ports were used: Two 10-millimeter (mm) ports and two 5-mm ports. Intraoperatively, some modifications were adopted when deemed necessary by the surgeon. These included decompression of the gallbladder, sutures to control the cystic duct, and placement of a closed suction drain in the subhepatic space. In the postoperative period, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and analgesics were given to the patients as required. The severity of pain during the first two postoperative days was assessed daily by the patient using a visual analog scale of 0 to 10. Feeding was resumed as soon as tolerated and i.v. antibiotics were replaced by oral antibiotics. After discharge, patients were followed-up for one year.

Statistical analysis

All data obtained were entered into the database and analyzed by means of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software using appropriate statistical tests like Fisher's exact test or paired t-test as and when needed. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient demographics

The study comprised 60 cases (30 in each group). Age distribution in both groups was comparable, with no statistically significant difference observed (P > 0.05). The mean age of patients in the early and delayed groups was 39.83 ± 8.25 years and 38.27 ± 9.82 years, respectively. Out of 60 cases, 12 were male and 48 were female. The male:female ratio was 1:4, and the difference between the two groups was statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

Clinical profile and laboratory investigations of patients in the two groups

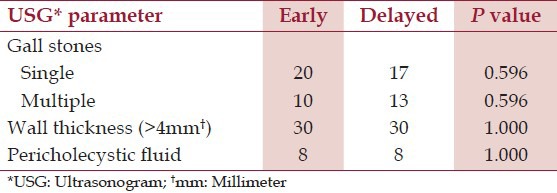

Pain right hypochondrium (RHC) was present in all patients. Nausea/vomiting was present in 22 patients in the early group and 26 patients in the delayed group. Fever was noted in 12 patients in the early group and 11 patients in the delayed group. Six patients presented with an additional history of RHC lump. However, no statistically significant difference was observed in the presentation between the two groups (P > 0.05). Findings of physical examination of patients in the two groups are presented in Table 1. Routine blood investigations and ultrasonographic parameters of patients in the two groups are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of physical findings of patients in the two groups

Table 2.

Routine blood investigations of the patients in the two groups

Table 3.

Ultrasononogram parameters of patients in the two groups

Operative details and complications

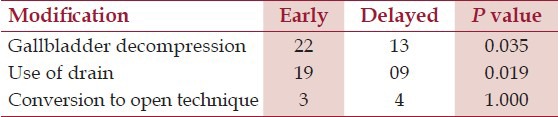

Table 4 shows various modifications in the operative technique in the two groups. There was statistically significant difference in terms of decompression of gallbladder and placement of subhepatic drain. However, no statistically significant difference was observed in the conversion rate. The reasons for conversion to open surgery in the early group were the friable and edematous gall bladder, which tore when grasped; and in the delayed group, the main reason for conversion was difficulty in gall bladder exposure and dense adhesions obscuring the anatomy of Calot's triangle.

Table 4.

Modification in operative technique in the two groups

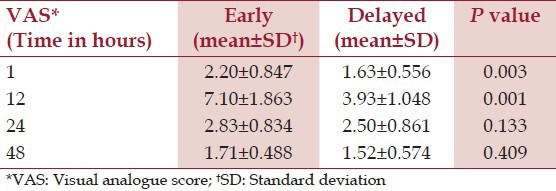

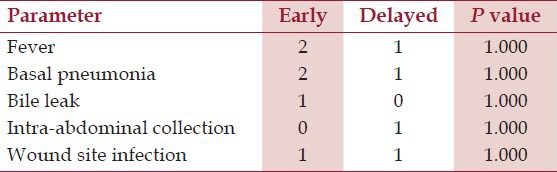

The mean operating time in the early group was 98.83 minutes, while that in the delayed group was only 80.67 minutes. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The mean blood loss in the early group was 173.33 ml, whereas that in the delayed group was only 101.00 ml. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Intraoperative blood loss was estimated by measuring suction canisters pre- and postoperatively and subtracting the amount of irrigation used from it.Table 5 shows postoperative pain scores (visual analog score) in the two groups. There was a statistically significant difference in the pain score of the two groups at 1 and 12 hours. However, no statistically significant difference was observed at 24 and 48 hours. There was no statistically significant difference in resumption of orals in the two groups (13 hours versus 10.7 hours in early versus delayed groups, respectively). Postoperative complications in the two groups are shown in Table 6. Mean hospital stay in the early group was 4.77 days, while that in the delayed group was 10.10 days. This difference was statistically significant. Mean loss of work differed significantly between the two groups and patients in the early group had a much shorter stay (14.5 days) away from work as against 21 days for the delayed group.

Table 5.

Comparison of postoperative pain scores in the two groups

Table 6.

Postoperative complications in the two groups

Discussion

Laparoscopic surgery has radically changed the field of general surgery, and with increasing experience, its applications are expanding rapidly. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the standard of care for symptomatic cholelithiasis. The pioneers of laparoscopic cholecystectomy initially considered acute cholecystitis to be a contraindication for laparoscopic surgery.[9] The main reason for a conservative approach was the concern of having a high risk of common bile duct injury due to edematous and inflamed tissues obscuring the anatomy in the Calot's triangle. However, with growing experience and greater technical skills, surgeons realized that these obstacles could be managed. Consequently, an increasing number of reports became available, demonstrating the feasibility of the laparoscopic approach for acute cholecystitis with an acceptable morbidity.[9,10]

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is found to be superior as a treatment for acute cholecystitis because of a shorter length of hospital stay, quicker recuperation, and earlier return to work without added morbidity. However, laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis has not become routine, because the timing and approach to the surgical management in patients with acute cholecystitis is still a matter of controversy.[6]

High conversion rates have been reported by different studies, ranging from 6% to 35%[11,12,13,14,15,16] for early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. The higher conversion rate obviates the advantages of an early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Therefore, it is argued that if delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy leads to a technically easier surgery with a lower conversion rate, it may be a better treatment option for acute cholecystitis. However, the belief that initial conservative treatment increases the chances of a successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy at a later date is probably not true, as found in this study. In our study, both the early and delayed groups had similar conversion rates. The reasons for conversion, however, were different. In the early group, the friable and edematous gall bladder tore when grasped. However, in the delayed group, the main reason for conversion was difficulty in gall bladder exposure and dense adhesions obscuring the anatomy of Calot's triangle.

An important issue in comparison of the two groups is the bile duct injury. None of the patients in either group had bile duct injury. One (3.33%) patient had bile leak in the early group due to distal partial obstruction by a small stone in distal common bile duct, which had slipped of gallbladder during dissection and was successfully removed by Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and the leak settled.

Several technical key points must be kept in mind when laparoscopic surgery is performed for acute cholecystitis. For good exposure of Calot's triangle, decompression of the gallbladder should be done early because this allows better grasping and retraction of the gallbladder. In our study, during early surgery, a distended and edematous gall bladder was encountered in 22 (73.33%) cases, which posed a difficulty in grasping and retraction of the gall bladder and also obscured the Calot's triangle. Decompression of gallbladder was done to visualize the anatomy of Calot's triangle. Gallbladder decompression was even done in 13 (43.33%) patients in the delayed group. A subhepatic drain was placed in 19 (63.33%) patients in the early group and in 9 (30%) patients in the delayed group. The reason for this was spillage of bile and stones during dissection of gallbladder from liver bed.

Delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy scored over early laparoscopic cholecystectomy as far as operating time is concerned. The difference could be explained because of few reasons like encountering a distended and edematous gall bladder, which needed decompression, more vascularity around the gallbladder, and Calot's triangle and omental adhesions, which needed meticulous dissection.

The average blood loss was more in the early group than in the delayed group; however, no patient required blood transfusion. The difference could be attributed to more vascularity around gallbladder and Calot's triangle in acute phase.

The total hospital stay in the delayed group was significantly longer than the early group because it included the total time spent during two admissions – one at the time of acute attack and, the second, admission for surgery 6-12 weeks later. Most studies published in international literature show a statistically significant difference in the total hospital stay.

Conclusion

The safety and efficacy of early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis were comparable in terms of mortality, morbidity, and conversion rate. However, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy allows significantly shorter total hospital stay and reduction in days away from work at the cost of significantly longer operating time and blood loss and offers definitive treatment at initial admission. Moreover, it avoids repeated admissions for recurrent symptoms. In conclusion, early operation within 72 hours of onset of symptoms has both medical and socioeconomic advantages and should be the preferred approach for patients managed by surgeons with adequate experience in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Shea JA, Berlin JA, Bachwich DR, Staroscik RN, Malet PF, Guckin MM. Indications and outcomes of cholecystectomy: A comparison of pre and post laparoscopic era. Ann Surg. 1998;227:343–50. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter JG. Acute cholecystitis revisited; Get it while it is hot. Ann Surg. 1998;227:468–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graves HA, Jr, Ballinger JF, Anderson WJ. Appraisal of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1991;213:655–64. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199106000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Salamah SM. Outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:400–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirmer BD, Edge SB, Dix J, Hyser MJ, Hanks JB. Treatment of choice for symptomatic cholelithiasis. Ann Surg. 1991;213:665–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199106000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirota M, Miura F, et al. Surgical treatment of patients with acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:91–7. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaheed A, Saler M, Majed KA, Ibrahim M, Habib M. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis vs chronic cholecystitis-A prospective comparision study. Kuwait Med J. 2004;36:281–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vchiyama K, Onishi H, Tani M. Timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Hepatogastroentrology. 2004;51:346–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kum CK, Goh PM, Issac JR, Tekant Y, Ngoi SS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1651–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson RG, Macintyre IM, Nixon SJ, Saunders JH, Varma JS, King PM. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a safe and effective treatment in severe acute cholecystitis. BMJ. 1992;305:394–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6850.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandler CF, Lane JS, Ferguson P, Thompson JE, Ashley SW. Prospective evaluation of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of acute cholecystitis. Am Surg. 2000;66:896–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox MR, Wilson TG, Luck AJ, Jeans PL, Padbury RT, Toouli J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute inflammation of the gallbladder. Ann Surg. 1993;218:630–4. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199321850-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller RE, Kimmelsteil FM. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:296–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00725943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rattner DW, Ferguson C, Warshaw AL. Factors associated with successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1993;217:233–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisen SM, Unger SW, Barkin JS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: The procedure of choice for acute cholecystitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;88:334–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker KA, Flowers JL, Bailey RW, Graham SM, Buell J, Imbembo AL. Laparoscopic management of acute cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 1993;165:508–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80951-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]