Abstract

Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) is one of the frequent manifestations of the disorder which is an inflammatory process due to fibroblast infiltration, fibroblast proliferation and accumulation of glycosaminoglycans. Eye irritation, dryness, excessive tearing, visual blurring, diplopia, pain, visual loss, retroorbital discomfort are the symptoms and they can mimic carotid cavernous fistulas. Carotid cavernous fistulas are abnormal communications between the carotid arterial system and the cavernous sinus. The clinical manifestations of GO can mimic the signs of carotid cavernous fistulas. Carotid cavernous fistulas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the GO patients especially who are not responding to the standard treatment and when there is a unilateral or asymmetric eye involvement. Here we report the second case report with concurrent occurrence of GO and carotid cavernous fistula in the literature.

Keywords: Carotid-cavernous fistula, endovascular treatment, Graves’ ophthalmopathy

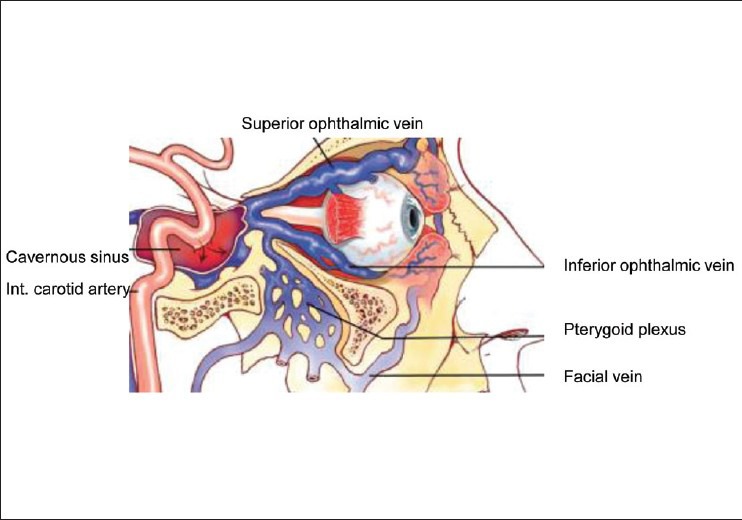

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disease characterized by diffuse goiter, infiltrative ophthalmopathy and dermopathy. Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) occurs in 40% of hyperthyroidism cases.[1] The eye-related symptoms are, eye irritation, dryness, excessive tearing, visual blurring, diplopia, pain, visual loss and retro-orbital discomfort. The signs are proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, orbital congestion, periorbital edema, conjunctival chemosis, ocular motility change, eyelid retraction and uncommonly compression of the optic nerve.[2,3] GO can be treated by systemic glucocorticoids (GCs), surgery, or both.[4] Carotid cavernous fistulas (CCF's) are abnormal communications between the carotid arterial system and the cavernous sinus [Fig. 1]. Anatomically they can be direct or indirect with high-flow or low-flow dynamics due to either traumatic or spontaneous causes. Clinical findings are head, ocular, and facial pain, pulsatile proptosis, chemosis, periorbital edema, conjunctival injection, double vision, glaucoma and, visual loss.[5]

Figure 1.

A direct carotid-cavernous sinus fistula resulting in vascular orbital congestion (It was adapted from Bhatti MT. Orbital syndromes. Semin Neurol 2007;27:269-87)

Here we report a case with simultaneous occurrence of GO and carotid cavernous fistula.

Case Report

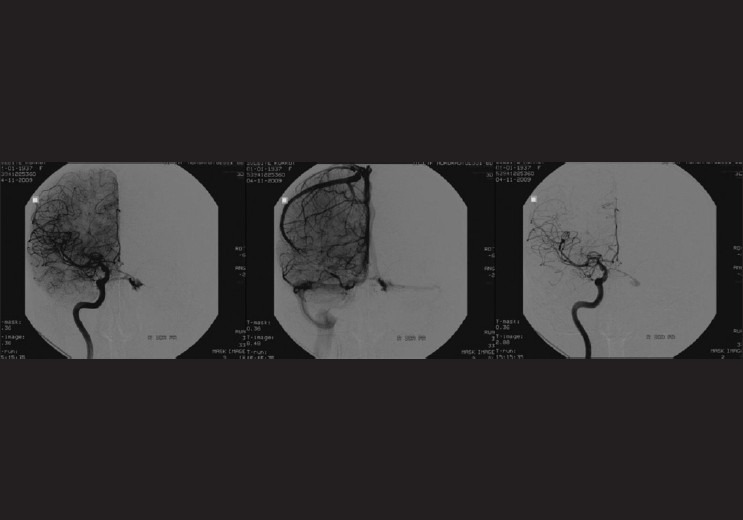

A 72-year-old woman who was diagnosed with Graves’ disease and mild bilateral ophthalmopathy 1 year ago and treated with propylthiouracil was admitted to our hospital because of grittiness, eye discomfort, proptosis, and swelling of both eyes; exophthalmos, eye pain, visual disturbance, conjunctive congestion and chemosis in the right eye [Fig. 2]. She had progressive visual disturbance on the right eye. The patient had undergone corticosteroid treatment with 16 mg/day methylprednisolone for 1 month and than 30 mg/day deflazacort for 2 months for the opthalmopathy. Her laboratory results were as follows fT4: 1.19 ng/dl (0.7-1.7), TSH: 2.24 mU/l (0.4-4), TSH receptor antibodies and thyroid peroxidase antibodies were positive. The orbital MRI images revealed exophtalmos in the right eye, an enlargement in the right extraocular muscle and in the right retro-orbital fatty tissue. The right optic nerve diameter was less than the left one. The patient's ophthalmopathy was diagnosed as asymmetrical thyroid ophthalmopathy but also, carotico-cavernous fistula was considered in differential diagnosis. A cerebral angiography was performed and a dural carotid cavernous fistula was observed on the right side [Fig. 3]. This dural CCF was draining through the right superior opthalmic vein as well as the left superior opthalmic vein via posterior intercavernous sinus connection. Endovascular treatment of the right-sided superior opthalmic vein drainage was accomplished by closing the right cavernous sinus with platinum coils. However, although the small left-sided drainage was persisted since then, there was no left-sided superior opthalmic vein drainage and therefore right-sided drainage was decided to be left untreated. After 2 months, the symptoms regressed, a full vision of right eye was obtained and radiological improvement was noted [Fig. 2].

Figure 2.

Exophthalmos, proptosis, periorbital swelling, conjunctive congestion and chemosis in the right eye, ocular statement 2 months after embolization treatment

Figure 3.

Cerebral angiography shows a dural carotid cavernous fistula on the right side draining through the right superior opthalmic vein as well as the left superior opthalmic vein via posterior intercavernous sinus connection (arterial and venous phase)

Discussion

Graves’ disease occurs between 20 and 50 years of age and in 2 % of women. Ophthalmopathy is one of the frequent manifestations.[2] Proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, orbital congestion, periorbital edema, conjunctival chemosis, ocular motility change, eyelid retraction, and uncommonly compression of the optic nerve are the most common manifestations of GO.[1] Patients with severe ophthalmopathy have high titers of thyrotropin-receptor antibodies.[6] Up to half of all Graves’ patients have ophtalmopathy; more than 70% of the remaining half can be demonstrated to have ophthalmopathy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination of the orbits. Whenever GO is a possible diagnosis, particularly in a patient with unilateral exophthalmos, orbital imaging is always indicated.[3] Villadolid et al. reported that 71% of untreated Graves’ cases with no clinical opthalmopathy showed extraocular muscle enlargement on MRI.[7] According to the consensus statement, GO can be treated by systemic GCs, surgery, or both. Patients with sight-threatening GO should be treated with i.v. GCs as the first-line treatment; if the response is poor after 1–2 weeks, they should be submitted to urgent surgical decompression. The treatment of choice for moderate-to-severe GO is i.v. GCs (with or without orbital radiotherapy) if the orbitopathy is active; surgery should be considered if the orbitopathy is inactive.[4] Although clinically unilateral GO occurs occasionally, orbital imaging generally confirms the presence of asymmetric bilateral disease.[6] Idiopathic orbital inflammation, orbital cellulitis, primary or metastatic tumors of the orbit, orbital hemorrhage and carotid cavernous fistulas should be considered in differential diagnosis of an asymmetric or unilateral eye involvement.[3]

Carotid cavernous fistulas develop between the cavernous sinus and carotid arteries as a result of abnormal connections. Pulsatile proptosis, chemosis, periorbital edema, conjunctival injection, head, eye, or facial pain, double vision, glaucoma, and loss of vision are the clinical symptoms. The gold standard for the diagnosis is catheter angiography. CT and MRI may show enlargement of the extraocular muscle or the superior ophthalmic vein. Twenty to fifty percent of all dural carotid cavernous fistulas can be closed spontaneously; most of them can also be closed by the endovascular embolization treatment.[5]

To the best of our knowledge of the medical literature, there is only one case report in which the carotid cavernous fistula and GO occur concurrently. Lore et al. reported a female patient diagnosed with Graves’ disease with bilateral mild ophthalmopathy. After radioiodine and methimazole treatment she was admitted to the hospital upon worsening of the clinical signs of ophthalmopathy. The symptoms in the left eye improved after intravenous corticosteroid treatment. CT image findings revealed an enlargement of the right extraocular muscles and a marked prominence of the ipsilateral superior ophthalmic vein. Cerebral angiography showed a dural CCF and clinical improvement was obtained following endovascular treatment.[8]

In our case, the patient who was diagnosed with Graves’ disease with mild bilateral ophthalmopathy 1 year ago received propylthiouracil treatment since then. Her following eye symptoms can occur both in GO and CCF. Asymmetrical thyroid ophthalmopathy was considered as the initial diagnosis, but the MRI findings and the symptoms of the right eye lead us to exclude CCF in differential diagnosis. In cerebral angiography a dural carotid cavernous fistula was observed, and after endovascular treatment full vision was obtained at the right eye. The diagnosis of GO was based on the presence of symptoms and signs of both eyes and on the radiological findings. The presence of the thyrotropin-receptor antibodies stand by the diagnosis of GO. GO was seen together with CCF in our case. These two unusual conditions could be simultaneously occur in the same eye. Increased vascularity, ocular and intracranial pressure changes, pressure on draining veins are all potential pathophysiological etiologies in patients with Graves’ disease that could create a situation conducive to fistula formation.

In conclusion, CCF's should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the GO who are not responding to the standard treatment and when there is a unilateral or asymmetrical eye involvement.

Acknowledgements

The patient gave her informed content concerning the presentation of her full portrait. The author would like to thank the patient for providing consent to use her photograph in this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ginsberg J. Diagnosis and management of Graves’ disease. CMAJ. 2003;168:575–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiebel-Kalish H, Robenshtok E, Hasanreisoglu M, Ezrachi D, Shimon I, Leibovici L. Treatment modalities for Graves’ ophthalmopathy: Systematic review and metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2708–16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Kaissi S, Frauman AG, Wall JR. Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: a practical guide to classification, natural history and management. Intern Med J. 2004;34:482–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartelena L, Baldeschi L, Dickinson AJ, Eckstein A, Kendall-Taylor P, Marcocci C, et al. Consensus statement of the European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) on management of GO. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:273–85. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatti MT. Orbital syndromes. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:269–87. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1468–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villadolid MC, Yokoyama N, Izumi M, Nishikawa T, Kimura H, Ashizawa K, et al. Untreated Graves’ disease patients without clinical ophthalmopathy demonstrate a high frequency of extraocular muscle (EOM) enlargement by magnetic resonance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2830–33. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.9.7673432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lore F, Polito E, Cerase A, Bracco S, Loffredo A, Pichierri P, et al. Carotid Cavernous Fistula in a patient with Graves’ Ophtalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3487–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]