Abstract

We report the application of capillary isoelectric focusing for quantitative analysis of a complex proteome. Biological duplicates were generated from PC12 cells at days 0, 3, 7, and 12 following treatment with nerve growth factor. These biological duplicates were digested with trypsin, labeled using eight-plex iTRAQ chemistry, and pooled. The pooled peptides were separated into 25 fractions using reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC). Technical duplicates of each fraction were separated by capillary isoelectric focusing (cIEF) using a set of amino acids as ampholytes. The cIEF column was interfaced to an Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer with an electrokinetically-pumped sheath-flow nanospray interface. This HPLC-cIEF-ESIMS/MS approach identified 835 protein groups and produced 2,329 unique peptides IDs. The biological duplicates were analyzed in parallel using conventional strong-cation exchange (SCX) – RPLC-ESIMS/MS. The iTRAQ peptides were first separated into eight fractions using SCX. Each fraction was then analyzed by RPLC-ESI-MS/MS. The SCX-RPLC approach generated 1,369 protein groups and 3,494 unique peptide IDs. For protein quantitation, 96 and 198 differentially expressed proteins were obtained with RPLC-cIEF and SCX-RPLC, respectively. The combined set identified 231 proteins. Protein expression changes measured by RPLC-cEIF and SCX-RPLC were highly correlated.

Introduction

Protein quantification is valuable in understanding changes in biological systems accompanying development, differentiation, and disease [1, 2]. There are several mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomic techniques available, including label free quantitation [3–5], chemical labeling [6–8], and metabolic labeling [9, 10].

Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) is a chemical labeling method that produces protein identification from peptide fragments and quantification from low mass reporter ions at the MS/MS level [6, 11, 12]. Up to eight channels are available that can be used to quantify up to eight samples simultaneously [13]. The large number of channels is valuable in the study of multiple sample stages in space and time [14].

In the vast majority of iTRAQ based proteomic studies, the labeled peptides are first fractionated by SCX, and each fraction is then analyzed by RPLC-MS/MS [6]. During this two-dimensional SCX-RPLC separation, the excess iTRAQ reagent is efficiently removed at the SCX fractionation step.

Several groups have begun to investigate the use of capillary electrophoresis (CE) as an alternative technique to liquid chromatography for the analysis of relatively simple mixtures [15–22]. Several of these studies demonstrated that CE-ESI-MS/MS and RPLC-ESI-MS/MS provide complementary peptide identifications [15, 16, 19], and combination of these two techniques improves the number of peptide IDs and protein sequence coverage.

Capillary isoelectric focusing (cIEF) is a form of capillary electrophoresis that provides both powerful enrichment and separation of proteins and peptides based on the analyte’s isoelectric point (pI) [23]. Compared to zone electrophoresis, the focusing properties of cIEF allow use of much larger injection volumes, which facilitates analysis of very dilute analyte [24–26].

On-line coupling of cIEF with ESI-MS for analysis of protein digests is challenging due to the presence of ampholytes, which generate strong interfering signals in the same m/z range as tryptic digests [27–29]. We have recently demonstrated that amino acids can act as ampholytes to create the pH gradient in cIEF while generating very low background signals in the m/z range for tryptic peptides [30]. We observed that the background signal intensity generated by the amino acids was a factor of 30 lower than that generated by commercial ampholytes, which was valuable in the study of low abundance peptides by ESI-MS/MS.

The PC12 cell line is derived from pheochromocytoma of the rat adrenal medulla. These cells differentiate into neuronal-like cells after incubation with nerve growth factor (NGF) [31]. This feature makes differentiated PC12 cells very useful as a model system for neurobiological and neurochemical studies. Recently, Kobayashi et al. used fourplex iTRAQ to identify proteins related to neuronal differentiation in NGF-treated PC12 cells [32]. In order to maximize the number of identifications, these authors fractionated the iTRAQ labeled peptides by SCX, and the fractionated peptides were then analyzed by RPLC-MALDI-MS/MS and RPLC-ESI-MS/MS. In total, 72 differentially expressed proteins were identified; 39 proteins were up-regulated and 33 down-regulated. Only one NGF-treatment time point was compared with the control.

In this work, iTRAQ eight-plex was applied for the large-scale quantitative proteomic analysis of NGF-treated PC12 cells. Four time points were analyzed in biological duplicate: untreated control and NGF-treatment for 3, 7 and 12 days. We employed cIEF-ESI-MS/MS with amino-acid based ampholytes to analyze peptides that had been first fractionated by RPLC. These results were combined with the results using SCX fractionation followed by RPLC-ESI-MS/MS. A total of 231 differentially expressed proteins were identified.

Material and methods

Materials

Bovine pancreas TPCK-treated trypsin, urea, ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3), dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide (IAA), and amino acids (glutamate, asparagine, glycine, proline, histidine, and lysine) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acetonitrile (ACN) and formic acid (FA) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Methanol was purchased from Honeywell Burdick & Jackson (Wicklow, IE, USA). Water was deionized by a Nano Pure system from Thermo Scientific (Marietta, OH, USA). Fused capillaries were purchased from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ, USA). iTRAQ eight-plex reagents were purchased from AB Sciex (Foster City, CA, USA). Complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail (provided in EASYpacks) was purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN, USA). The 2-D Clean-Up kit used for protein precipitation was ordered from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA).

RPMI 1640 medium, fetal bovine serum, and horse serum were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Mammalian Cell-PE LB™ Buffer for cell lysis was purchased from G-Biosciences (St. Louis, MO, USA). Rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12s, strain CRL-1721) were purchased fromATCC. Cell culture flasks were purchased from Corning (Tewksbury, MA). Mouse collagen IV was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and Trypsin/EDTA solutions were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell culture, cell lysis and trypsin digestion

Cell culture flasks were coated with mouse collagen IV according to the manufacturer’s instructions prior to PC12 seeding because PC12 cells demonstrate weak adherence to plastic [31]. PC12 cells were routinely grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 2 mM GlutaMAX, amphotercin B, streptomycin, and penicillin. To initiate the differentiation of PC12 cells into neuronal like cells (dPC12s), the growth medium was supplemented with neuronal growth factor at a concentration of 50 ng/mL and cells were seeded onto a fresh collagen-IV coated flask.

Initially, the PC12 cells used in this experiment were grown without NGF. To begin sample collection, a confluent PC12 flask was split in a 1:4 ratio. One fraction was used as a control group consisting of non-differentiated PC12 cells that were immediately harvested. The three other fractions were separately seeded onto three collagen-IV coated flasks and NGF-containing medium was added to induce neuronal differentiation. dPC12s were then separately harvested three, seven, and twelve days after the introduction of NGF into the cellular medium. To harvest, cells were first washed three times with calcium and magnesium-free phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Next, cells were removed using a 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution and washed with NGFcontaining RPMI growth medium to remove any residual trypsin. Cells were then washed with PBS three times, followed by cell lysis. The experiment was repeated for a biological duplicate beginning with another confluent PC12 flask.

The cell pellets after PBS washing were suspended in 500 µL mammalian cell-PE LB™ buffer (pH 7.5) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor and sonicated on ice for 15 min with a Branson Sonifier 250 (VWR Scientific, Batavia, IL). Subsequently, the cell lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for measurement of protein concentration with the BCA method.

60 µg of each protein sample was precipitated using a 2-D Clean-Up kit according to the manufacture’s protocol. Protein pellets were dissolved in 30 µL of 100 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) with 8 M urea and denatured at 50 ˚C for 30 min followed by reduction with DTT (8 mM) at 65 ˚C for 1 h and alkylation with IAA (20 mM) at room temperature for 30 min in dark. Then 120 µL of 100 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) was added to reduce the concentration of urea to less than 2 M. The proteins were digested by incubation with trypsin at a trypsin/protein ratio of 1/30 (w/w) for 12 h at 37 ˚C. Digests were then acidified with 0.5% formic acid (final concentration) to terminate the reaction. Tryptic digests were desalted with tC18 SepPak columns (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and lyophilized with a vacuum concentrator from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Marietta, OH, USA).

iTRAQ Sample Labeling

The desalted peptides were labeled with eight-plex iTRAQ reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For 60 µg peptides, 1 unit of labeling reagent was used. Peptides were dissolved in 30 µL of dissolution buffer and 50 µL of isopropanol was added into each iTRAQ reagent. Reagents 113 and 114 were used to treat biological duplicates from untreated cells, reagents 115 and 116 to treat biological duplicates from NGF-stimulated cells after 3 days, reagents 117 and 118 to treat biological duplicates from NGF-stimulated cells after 7 days, and reagents 119 and 121 to treat biological duplicates from NGF-stimulated cells after 12 days. After 2 h incubation at room temperature, the differentially labeled peptides were pooled, lyophilized, desalted, and lyophilized again. The labeled peptides were stored at −80 °C before use.

RPLC Fractionation

An aliquot of the iTRAQ labeled digests was fractionated on a Waters HPLC using an Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 µm). The flow rate was 1 mL/min. A gradient was used as follows (A: 1% ACN, 0.1% TFA; B: 98% ACN, 0.1% TFA): 0–8 min, 0% B; 8–38 min, 0–40% B; 38–39 min, 40–80% B; 39–49 min, 80% B; 49–50 min, 80–0% B; 50–60 min, 0% B. In total, 275 µg of labeled peptides was loaded on the column, and fractions were collected every one min from 16 min to 41 min (S-fig. 1 supporting material I). The 25 fractions were lyophilized and stored at −80 °C before cIEF-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

SCX Fractionation

An aliquot of the iTRAQ labeled digest was fractionated based on strong-cation exchange on a Waters HPLC instrument, using an Agilent ZORBAX 300-SCX column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 µm). The flow rate was 1 mL/min. A gradient was used as follows (A: 10 mM potassium phosphate in 20% (v/v) ACN, pH 3.0; B: 10 mM potassium phosphate in 20% (v/v) ACN with 1 M KCl, pH 3.0): 0–8 min, 0% B; 8–30 min, 0–50% B; 30–31 min, 50–100% B; 31–40 min, 100% B; 40–41 min, 100–0% B; 41–50 min, 0% B. In total, 130 µg of labeled peptides was loaded on the column and fractions were collected every 2 minute from 16 to 32 min (S-fig. 2 in supporting material I). The eight collected fractions were lyophilized, desalted, and lyophilized again. Fractions were stored in −80 °C before RPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

cIEF-ESI-MS/MS analysis

An electrokinetically pumped electrospray interface [17] developed in our lab was used to couple the cIEF column to an Orbitrap mass spectrometer. A commercial linear polyacrylamide coated capillary (50 µm i.d./150 µm o.d., 50 cm long) was used for the cIEF separation. FA (0.1%, pH 2.5) was used as anolyte and 0.3% ammonium hydroxide (pH 11) was used as catholyte during focusing. Glutamate (5 mg), asparagine (5 mg), glycine (5 mg), proline (20 mg), histidine (20 mg), and lysine (20 mg) were dissolved in 10 mL water to prepare ampholytes used in the cIEF-MS/MS separations. Each RPLC fraction was redissolved in 30–50 µL of the six-amino acid mixture solution. For cIEF-ESI-MS/MS analysis, the separation capillary was filled with the digests by pressure at 2 psi for 3 min. Next, the digests were focused in the capillary by applying a 400 V/cm field for 10 min. After focusing, the cathode end of the capillary was inserted into the emitter of the electrospray interface and chemical mobilization was performed based on the sheath flow buffer (10% methanol, 0.1% formic acid). The electric field across the capillary was kept at 330 V/cm during mobilization, and the electrospray voltage was set as 1.5 kV. Each sample was analyzed in technical duplicate.

A LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used in the programmed data dependent acquisition mode. Full MS scans were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer over the m/z 395–1800 range with resolution 30,000 (at 400 m/z). The ten most intense peaks with charge state ≥ 2 were fragmented in the higherenergy collisional dissociation (HCD) cell, and analyzed by the Orbitrap mass analyzer with resolution 7,500. One microscan was used. Normalized collision energy was set as 40%. For MS and MS/MS spectra acquisition, the maximum ion inject time was set as 500 ms and 250 ms, respectively. The precursor isolation width was 2 Da. The target values for MS and MS/MS were set as 1.00E+06 and 5.00E+04, respectively. Dynamic exclusion was applied for the experiments. Peaks selected for fragmentation more than once within 25 s were excluded from selection for 25 s.

UPLC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis

The desalted digests from SCX fractionation were redissolved in 2% ACN and 0.1% FA, followed by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. A nanoACQUITY UPLC system with a UPLC BEH 130 C18 column (Waters, 100 µm × 100 mm, 1.7 µm) was coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap Velos instrument for peptide separation and identification. The RPLC gradient (A: 0.1% (v/v) FA and 2% (v/v) ACN; B: 0.1% (v/v) FA and 98% (v/v) ACN) was as follows: 0–12 min, 2% B; 12–14 min, 2–10% B; 14–64 min, 10–40% B; 64–65 min, 40–85% B; 65–75 min, 85% B; 75–76 min, 85–2% B; 76–90 min, 2% B. The flow rate was 0.7 µL/min. The electrospray voltage was 1.5 kV. For each run, 25% of each fraction sample was loaded for analysis, and each fraction was analyzed in technical duplicate. The MS parameters were the same as that used for cIEF-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

Data analysis

Database searching of the RAW files and iTRAQ based protein quantitation was performed in Proteome Discoverer 1.3. MASCOT 2.2.4 was used for database searching against SwissProt database with taxonomy as rat (7,458 sequences). Database searching against the corresponding reversed database was also performed for evaluation of false discovery rate (FDR) [33, 34]. The database searching parameters included full tryptic digestion and allowed up to two missed cleavages, precursor mass tolerance 10 ppm, fragment mass tolerance 0.05 Da. Carbamidomethylation (C) and iTRAQ eight-plex (N-term of peptides and K) were set as fixed modifications. Oxidation (M), deamidated (NQ), and iTRAQ eight-plex (Y) were set as variable modifications.

On peptide level, the MASCOT significance threshold 0.01 (99% confidence) was used to filter the identifications. On protein level, protein grouping was enabled and strict maximum parsimony principle was applied. The number of proteins reported in this manuscript are the protein group number.

For iTRAQ based protein quantification, iTRAQ 8-plex (Thermo Scientific instruments) method included in Proteome Discoverer 1.3 was used. For peak integration, integration window tolerance was set as 20 ppm and integration method as most confident centroid. The median iTRAQ ratios of control sample (day0: 113+114) were used to normalize the ratios of NGF treated samples (day3: 115+116, day7: 117+118, day12: 119+121). Only unique peptides were used for protein quantification. Proteins quantified with at least a two-fold change (average iTRAQ ratio >2.0 or < 0.5) were considered to be differentially expressed proteins.

Results and discussion

RPLC-cIEF-ESI-MS/MS and SCX-RPLC-ESI-MS/MS for dPC12 protein and peptide identification

In the work, two approaches, offline RPLC-cIEF-ESI-MS/MS (RPLC-cIEF) and SCX-RPLC-ESI-MS/MS (SCX-RPLC), were used for PC12 cell proteome analysis.

For RPLC-cIEF analysis, the iTRAQ-labeled dPC12 peptides were first fractionated based on hydrophobicity using RPLC, and the fractionated peptides were further separated based on pI using cIEF, followed by ESI-MS/MS analysis. Because RPLC was used as the first dimension, no desalting step is required before further cIEF-ESI-MS/MS analysis, which simplifies sample handling. In addition, because the iTRAQ reagent does not have a pI, excess iTRAQ reagent is removed during the focusing step, which avoids reagent interference during MS analysis. 25 fractions were collected from the reversed-phase chromatographic dimension and each fraction was further analyzed by cIEF-ESI-MS/MS in technical duplicates. The experimental design is summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental design for RPLC-cIEF-ESI-MS/MS and SCX-RPLC-ESI-MS/MS for eight-plex iTRAQ quantitative proteomic analysis of differentiation of PC12 cell induced by NGF.

After MASCOT database searching, 2,329 peptides corresponding to 835 protein groups were identified. The protein and peptide lists are shown in Supporting material II. This data set is by far the largest bottom-up proteomic analysis generated by cIEF-MS/MS method.

The same samples were also analyzed by SCX-RPLC, which is the standard method used for iTRAQ based protein quantification [6, 11, 32]. In this approach, we first separated peptides using SCX, followed by a second dimension separation based on hydrophobicity using RPLC, followed by MS/MS analysis. The excess iTRAQ reagent was removed during the SCX separation step. For this approach, eight fractions were collected from the first SCX dimension, and each fraction was further analyzed by RPLC-ESI-MS/MS in technical duplicates.

After MASCOT database searching, 3,494 peptides corresponding to 1,369 protein groups were identified by the SCX-RPLC approach. The results are shown in Supporting material II.

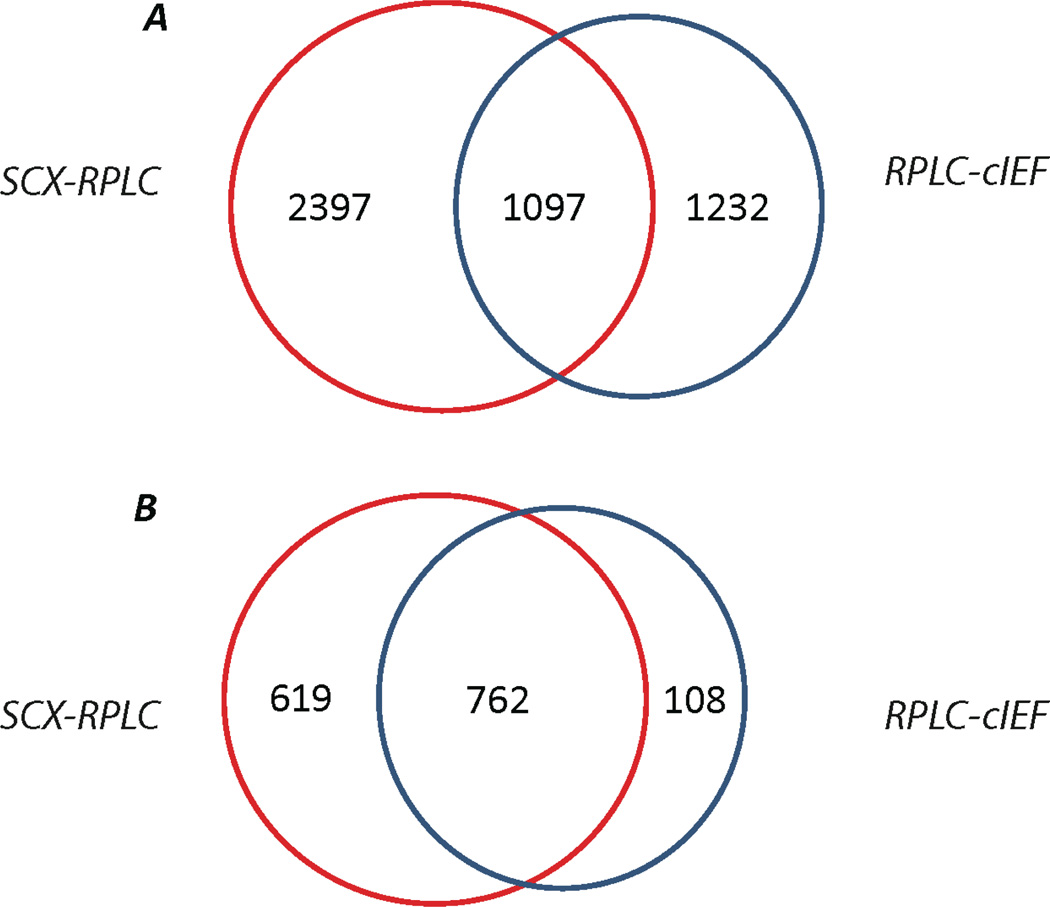

The SCX-RPLC dataset is ~50% larger than the number of IDs generated by RPLC-cIEF. These two approaches were complementary at the peptide level and produced good agreement at the protein level, Fig. 2. Combination of these two approaches yields 35% more peptides than the traditional SCX-RPLC approach. At the protein level, about 87% (762) of the proteins identified by RPLC-cIEF were also identified by SCX-RPLC. As expected, higher average sequence coverage of proteins was obtained from combination of the results (9.2%) compared with SCX-RPLC (7.1%) and RPLC-cIEF (8.6%) alone.

Figure 2.

Overlap of peptides (A) and proteins (B) identified by SCX-RPLC and RPLC-cIEF approaches.

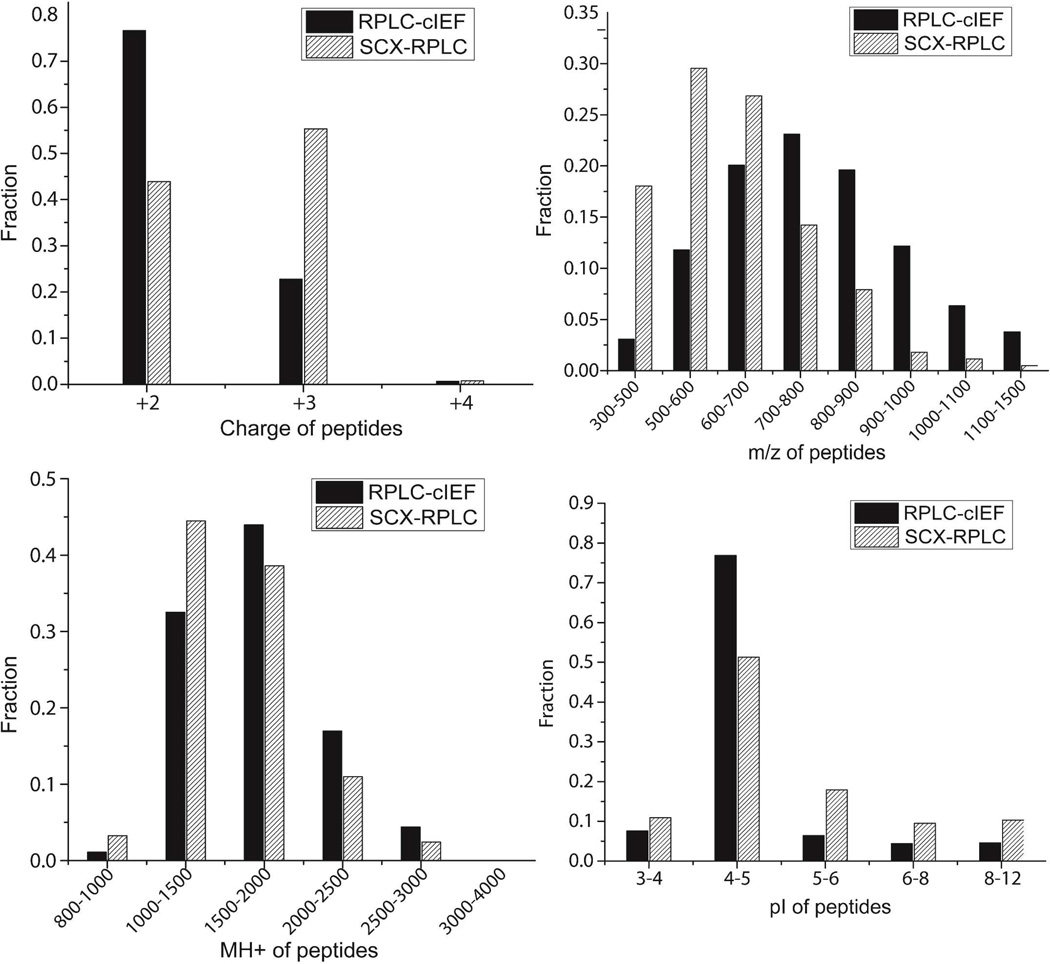

To understand the complementary of the SCX-RPLC and RPLC-cIEF approaches at the peptide level, charge, m/z, MH+, and pI distributions of peptides were determined, Fig. 3. The RPLC-cIEF approach tends to identify peptides with lower charge compared to SCX-RPLC (Fig. 3A). This result is likely due to ionization suppression of peptides by the amino acids used as ampholytes [30], which lowers the peptides’ charge. The assumption agreed with the relationship between charge and MH+ of peptides from the two approaches, S-Fig.3 in supporting material I. Larger peptides tends to have a higher charge, and for the same charge, the average MH+ of peptides from RPLC-cIEF is higher than that from SCX-RPLC, which indicated that greater peptide ionization suppression was generated by cIEF-ESI compared with RPLC-ESI. In addition, RPLC-cIEF tends to identify peptides with higher m/z and higher MH+ (Fig. 3B and C). Because of the lower charge of peptides that was produced by RPLC-cIEF, the m/z of peptides tends to be higher than that by SCX-RPLC. Interestingly, the distribution of peptide m/z generated by RPLC-cIEF is flatter than by SCX-RPLC, and the RPLC-cIEF mass spectra are not as crowded as from SCX-RPLC (S-Fig. 4 in supporting material I), which results in a higher probability for identification of larger peptides (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Distributions of charge, m/z, MH+, and pI of peptides from SCX-RPLC and RPLC-cIEF.

The two approaches produced similar pI distributions (Fig.3 D). Because the amino-acid based cIEF produced very high resolution for peptides with pI 4–5 [30], the approach tends to identify peptides with pI in this range.

We also analyzed the distribution of GRAVY value of the peptides from both approaches (S-Fig. 5 in supporting material I). The GRAVY value is a parameter to evaluate the peptide hydrophobicity, and positive and negative values mean hydrophobic and hydrophilic peptides, respectively. The two approaches yield similar GRAVY value distributions.

Evaluation of RPLC-cIEF and SCX-RPLC- for proteome quantification of PC12 cell differentiation by eight-plex iTRAQ

Both RPLC-cIEF and SCX-RPLC were used for protein quantification by 8-Plex iTRAQ. PC12 cells were treated with NGF for 0, 3, 7, 12 days. The outgrowth of neuronal-like processes was observed during NGF treatment, consistent with the literature [31]. The number, length, and density of the processes increased continuously as the treatment time increased from 0 to 12 days, S-Fig.6 in supporting material I. To obtain more confident protein quantitation results, biological duplicates were performed for each time point, Fig. 1. Proteins with significant changes during differentiation were identified by filters as follows: 1) they had to be present in all time points and in both biological duplicates for each time point; 2) changes between time points had to be greater than 2-fold (iTRAQ ratio >2 or <0.5). The conventional SCX-RPLC approach identified 198 differentially expressed proteins. The RPLC-cIEF approach identified 96 differentially expressed proteins. In total, 63 differentially expressed proteins were found by both approaches, and 231 differentially expressed proteins were identified by combining the results from these two approaches.

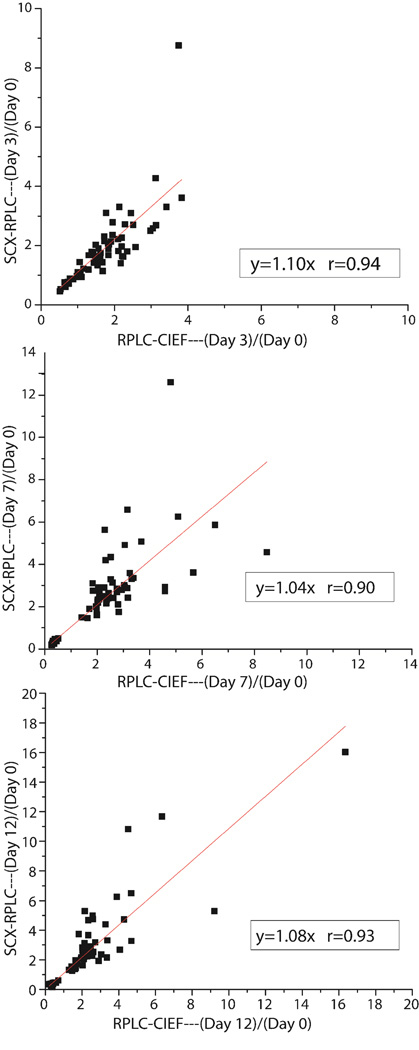

We analyzed the correlation of ratios of the differentially expressed proteins (63) identified by both approaches, Fig. 4. The protein ratios obtained from the two approaches agreed well between different time points (slope close to 1.0 and r value equal to or greater than 0.9). cIEF-ESI-MS/MS and RPLC-ESI-MS/MS generated consistent protein quantitation.

Figure 4.

Correlation of protein ratio between RPLC-cIEF and SCX-RPLC at different time points.

We further analyzed the peptide ratio distributions of four selected differentially expressed proteins (neurosecretory protein VGF [35], peripherin [36, 37], annexin A2 [38] and 14-3-3 protein γ [39]) identified by both approaches, S-Fig.7 in supporting material I. The change in protein expression at different time points from both approaches agreed well for the all four proteins. Interestingly, for neurosecretory protein VGF, RPLC-cIEF produced more peptides for protein quantification than SCX-RPLC.

S-Table 1 compares these results with an earlier quantitative proteomic study of PC12 cell [32]. In reference [32], iTRAQ 4-plex was used to determine protein abundance changes with and without NGF treatment (biological duplicate for each point). Two protocols, offline SCX-RPLC-MALDI-MS/MS and SCX-RPLC-ESI-MS/MS, were used for protein quantitation analysis, and 72 differentially expressed proteins with more than 20% change (average iTRAQ ratio >1.20 or <0.83) were obtained.

We employed four time-points in our measurement and required a two-fold change in abundance for differential expression. Two approaches, RPLC-cIEF and SCX-RPLC, were applied for the protein quantitation analysis, and 231 differentially expressed proteins with greater than a two-fold change were identified. Only 27 of these proteins were in common in the two studies. The different number of differentially expressed proteins and low overlap may be due to the different number of time points used in the experiments (2 vs. 4 time points).

Biological analysis of differentially expressed proteins

We analyzed the quantitation information for identified integral membrane proteins (IMPs). IMPs lie at the critical junctions between intracellular compartments, cells, and their environments, and they play very important roles including intercellular communication, vesicle trafficking, ion transport, protein translocation/integration, and the propagation of signaling cascades [40, 41]. The proteomic level analysis of IMPs is challenging due to their hydrophobicity and generally low abundance [42]. In this work, traditional SCX-RPLC approach generated 232 IMPs with at least one transmembrane domains (TMDs, predicted by TMHMM (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) algorithm), and the RPLC-cIEF approach produced 104 IMPs, S-Table 2 in supporting material I. The number of TMDs of IMPs obtained by both approaches ranged from 1 to 17, and for IMPs with high number of TMDs (higher than 9), RPLC-cIEF approach generated consistent results with the conventional SCX-RPLC approach. About 12% of proteins identified by RPLC-cIEF (104/835) and 17% of proteins identified by SCX-RPLC (232/1369) were recognized as IMPs, respectively, and the percentage of IMPs from both approaches was similar. The results clearly indicated that RPLC-cIEF is useful for IMPs analysis.

Differential expression of the IMPs from the two approaches were determined. Traditional SCX-RPLC yielded 47 differentially expressed IMPs and 16 were obtained from the RPLC-cIEF approach; in total, 52 differentially expressed IMPs were produced by the two approaches, S-Table 3. For the differentially expressed IMPs, five IMPs were down-regulated, and 47 were up-regulated. To understand the potential relationship between these IMPs and PC12 cell differentiation, we analyzed the protein function and biological process information of the 52 differentially expressed IMPs obtained from the UniProt Protein Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) (www.uniprot.org). Two up-regulated IMPs, Integrin alpha-1 and Integrin beta-1 are receptors for collagen, and may assist attachment of the PC12 cells to the collagen-coated flask. Two other up-regulated proteins, cell surface glycoprotein MUC18 and neural cell adhesion molecule L1, are also involved in cell adhesion, neuron-neuron adhesion, neurite fasciculation, and the outgrowth of neurites. We also identified one up-regulated IMP, reticulon-4, as a developmental neurite growth regulatory factor for regulation of neurite fasciculation, branching, and extension in the developing nervous system [43]. For communication between neurons, neurotransmitters play a very important role. Generally, the neurotransmitters are packed into synaptic vesicles in the synapse of the axon terminal, and then released into the synaptic cleft via exocytosis. The released neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and bind the specific receptors in the dendrite membrane of another neuron [44]. Two up-regulated IMPs, Syntaxin-1A [45] and Synaptotagmin-5 [46], are involved in regulation of neurotransmitter secretion and exocytosis. Furthermore, the regulation of neurotransmitter secretion and exocytosis is usually Ca2+ dependent, and another up-regulated IMP, neuroplastin, is involved in elevation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration [47], positive regulation of neuron projection development [47], and positive regulation of long-term neuronal synaptic plasticity [48]. In addition, one up-regulated IMP, vesicular acetylcholine transporter, is involved in acetylcholine transport into synaptic vesicles [49]. As expected, several IMPs (phospholipase D3, NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 1, and lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase) involved in lipid biosynthesis and/or metabolism were also detected and are up-regulated during PC12 cell differentiation.

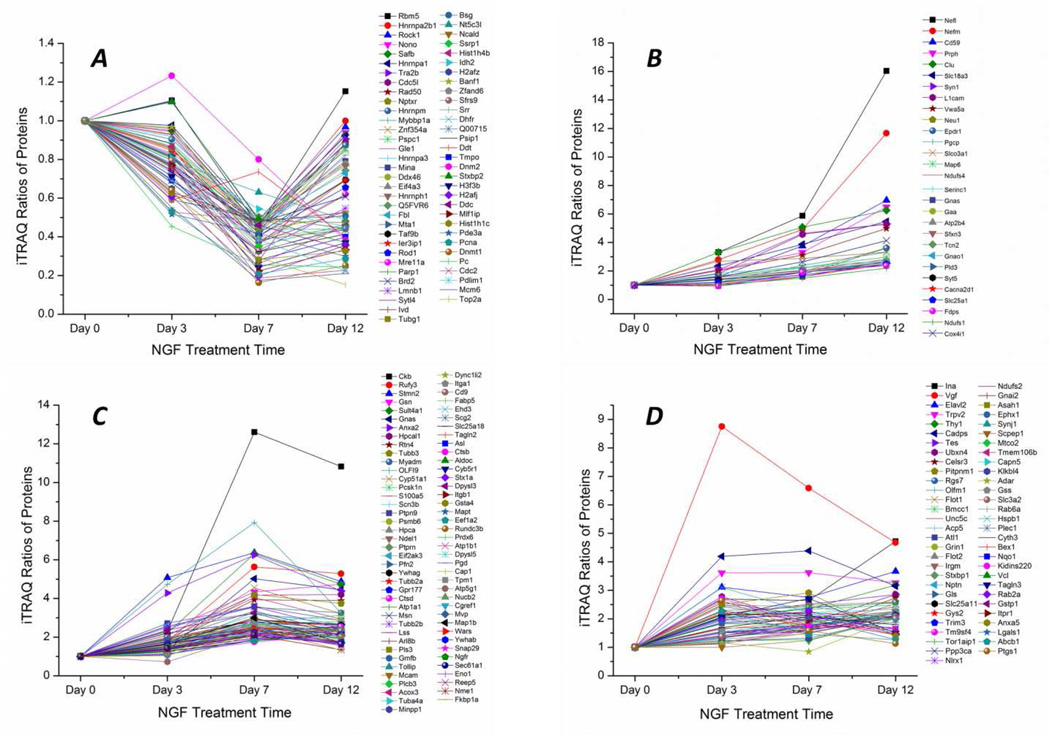

We also analyzed the protein expression trends of all identified differentially expressed proteins (231 proteins) across the four time points (day 0, 3, 7 and 12), Fig. 5. Information on all the differentially expressed proteins is also listed in supporting material II. The differentially expressed proteins were divided into four categories according to the trends of protein expression change after NGF stimulation. Sixty-four proteins were down-regulated or down-regulated first and then up-regulated (Fig. 5A). Twenty-nine proteins were continuously up-regulated (Fig. 5B). Seventy-nine proteins were up-regulated and then stabilized or down-regulated at the day 12 (Fig. 5C), and 59 proteins were not included in the three catalogues mentioned above (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Protein expression trends of all differentially expressed proteins (231 proteins) across the four time points (day 0, 3, 7 and 12) following NGF stimulation. For the differentially expressed proteins identified by both RPLC-cIEF and SCX-RPLC, the iTRAQ ratios of proteins from SCX-RPLC were used to generate the figure. Proteins were (A) down-regulated or down-regulated first and then up-regulated, (B) continuously up-regulated, (C) up-regulated and then stabilized or down-regulated at the day 12 time point, (D) and not included in the three catalogues mentioned above.

We further analyzed the molecular function and biological process of several up-regulated or down-regulated proteins according to information obtained from the UniProt Protein Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) (www.uniprot.org). Neurofilament light polypeptide (Nefl) and neurofilament medium polypeptide (Nefm) were up-regulated after NGF stimulation (Fig. 5B), and they are involved in the maintenance of neuronal character. Synapsin-1 (Syn1), also up-regulated, is a neuronal phosphoprotein that coats synaptic vesicles and functions in the regulation of neurotransmitter release. Neurosecretory protein VGF (Vgf) expression is always greater than the control; after an increase at day 3, its amount begins to decrease at day 7 and 12, Fig. 5D. Neurosecretory protein VGF is induced by NGF, is the precursor of a number of bioactive peptides, and regulates neuronal synaptic plasticity [50]. DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha (Top2a) is down-regulated after NGF stimulation (Fig. 5A), and it can control the topological states of DNA by transient breakage and subsequent rejoining of DNA strands. In addition, several histone proteins (histone H4, histone H2A.Z, histone H2B type 1, histone H3.3, histone H2A.J, histone H1.2) were also down-regulated after NGF stimulation.

Capillary isoelectric focusing as an alternative to reversed-phase liquid chromatography in bottom-up proteomics

The vast majority of bottom-up proteomics experiments employ liquid chromatography as the final separation method before tandem mass spectrometry analysis. This technology has been developed over the past three decades, and is quite robust and mature.

Nevertheless, there is a need for alternative separation technologies in quantitative proteomics. If the alternative separation technology is based on a different mechanism than RPLC, then the combination of the alternative technology with RPLC would increase the number of peptide identifications, increasing both the number of protein identifications and the sequence coverage.

The various capillary electrophoresis methods have attracted some attention as such an alternative. Capillary zone electrophoresis is the simplest form of capillary electrophoresis, consisting of a buffer filled capillary. We have shown that capillary zone electrophoresis produces essentially the same number of peptide and protein identifications as RPLC in the same analysis time for a medium-sized proteome, the secretome of M. marinum [19]. As we show elsewhere, capillary zone electrophoresis identifies over 1,250 peptides from an E. coli digest in a single 50-min separation [51].

In this paper, we consider capillary isoelectric focusing as another version of capillary electrophoresis. cIEF allows injection of a much larger sample volume than CZE, which enhances sensitivity. Classical cIEF is not suitable for bottom-up proteomics because of the interference produced by commercial ampholytes, whose m/z falls in the same range as tryptic peptides. We employ amino acids as ampholytes. These amphiprotic compounds produce a reasonable pH gradient and their low m/z essentially eliminating interference in bottom-up proteomics.

There have been a few applications of capillary electrophoresis for quantitative studies. Smith employed a 60-min cIEF separation of the tryptic digest of ICAT-labeled and metabolically-labeled yeast proteome in an early proof-of-principle experiment using accurate mass tags with electrospray ionization [27].

Over the past few years, studies have employed capillary electrophoresis coupled with MALDI for quantitative proteomics. Zuberovic employed CE-MALDI for the analysis of iTRAQ-labeled tryptic peptides from a cerebrospinal fluid sample [52]. Lingjun Li’s group has also employed CE-MALDI of isotopically labeled samples for comparative analysis of crustacean neuropeptides [53–55].

Finally, several investigators have employed solution-phase isoelectric focusing of proteins followed by reversed-phase separation of peptides [56–57]. These experiments employ relatively large volume chambers separated by membranes with specific pH values. During focusing, proteins migrate to the compartment confined by membranes with pH values flanking the pI of the protein. These proteins are then digested and subjected to reversed phase chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Chamber-based solution-phase isoelectric focusing is limited in the number of fractions that can be generated. Alternatively, capillary isoelectric focusing can be used to separate peptides; the peptides are loaded into trap columns, and each fraction is then analyzed by reversed-phase liquid chromatography [58]. This approach is limited by the relatively low injection volume available in the first dimension separation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM096767). We acknowledge the capable assistance of William Boggess and Matthew Champion of the University of Notre Dame’s mass spectrometry facility.

References

- 1.Ong SE, Mann M. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nchembio736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gstaiger M, Aebersold R. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:617–627. doi: 10.1038/nrg2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chelius D, Bondarenko PV. J. Proteome Res. 2002;1:317–323. doi: 10.1021/pr025517j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR., III Anal. Chem. 2004;76:4193–4201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao J, Opiteck GJ, Friedrichs MS, Dongre AR, Hefta SA. J. Proteome Res. 2003;2:643–649. doi: 10.1021/pr034038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson A, Schanfer J, Kuhn K, Kienle S, Schwarz J, Schmidt G, Neumann T, Hamon C. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:1895–1904. doi: 10.1021/ac0262560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boersema PJ, Raijmakers R, Lemeer S, Mohammed S, Heck AJR. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:487–494. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everley PA, Krijgsveld J, Zetter BR, Gygi SP. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:729–735. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400021-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueda K, Takami S, Saichi N, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, Kohno N, Katsumata M, Yamane A, Ota M, Sato T, Nakamura Y, Nakagawa H. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9:1819–1828. doi: 10.1074/mcp.2010/000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adav SS, Chao LT, Sze SK. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:012419. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012419. M111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadaliha M, Lee H, Pakzad M, Fathi A, Jeong S, Cho S, Baharvand H, Paik Y, Salekdeh GH. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamond AI, Uhlen M, Horning S, Makarov A, Robinson CV, Serrano L, Hart FU, Baumeister W, Werenskiold AK, Andersenaf JS, Vorm O, Linial M, Aebersold R, Mann M. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:017731. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.017731. O112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faserl K, Sarg B, Kremser L, Lindner H. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:7297–7305. doi: 10.1021/ac2010372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Fonslow BR, Wong CCL, Nakorchevsky A, Yates JR., III Anal. Chem. 2012;84:8505–8513. doi: 10.1021/ac301091m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojcik R, Dada OO, Sadilek M, Dovichi NJ. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010;24:2554–2560. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wojcik R, Li Y, MacCoss MJ, Dovichi NJ. Talanta. 2012;88:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Champion MM, Sun L, Champion PAD, Wojcik R, Dovichi NJ. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:1617–1622. doi: 10.1021/ac202899p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun L, Zhu G, Li Y, Wojcik R, Yang P, Dovichi NJ. Proteomics. 2012;12:3013–3019. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Wojcik R, Dovichi NJ, Champion MM. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:6116–6121. doi: 10.1021/ac300926h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramautar R, Heemskerk AAM, Hensbergen PJ, Deelder AM, Busnel J, Mayboroda OA. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:3814–3828. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hjertén S, Elenbring K, Kilar F, Liao JL, Chen AJ, Siebert CJ, Zhu MD. J. Chromatogr. 1987;403:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)96340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsay LM, Dickerson JA, Dovichi NJ. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:297–302. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsay LM, Dickerson JA, Dada O, Dovichi NJ. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:1741–1746. doi: 10.1021/ac8025948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dada OO, Ramsay LM, Dickerson JA, Cermak N, Jiang R, Zhu C, Dovichi NJ. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;397:3305–3310. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3595-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith RD, Pasa-Tolić L, Lipton MS, Jensen PK, Anderson GA, Shen Y, Conrads TP, Udseth HR, Harkewicz R, Belov ME, Masselon C, Veenstra TD. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:1652–1668. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200105)22:9<1652::AID-ELPS1652>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haselberg R, de Jong GJ, Somsen GW. Electrophoresis. 2011;32:66–82. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu G, Sun L, Wojcik R, Kernaghan D, McGivney IV JB, Dovichi NJ. Talanta. 2012;98:253–256. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu G, Sun L, Yang P, Dovichi NJ. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;750:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene LA, Tischler AS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:2424–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi D, Kumagai J, Morikawa T, Wilson-Morifuji M, Wilson A, Irie A, Araki N. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8:2350–2367. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900179-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Possenti R, Di Rocco G, Nasi S, Levi A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1992;89:3815–3819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marín-Vicente C, Guerrero-Valero M, Nielsen ML, Savitski MM, Gómez-Fernández JC, Zubarev RA, Corbalán-García S. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:529–540. doi: 10.1021/pr100742r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aletta JM, Shelanski ML, Greene LA. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4619–4627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacovina AT, Zhong F, Khazanova E, Lev E, Deora AB, Hajjar KA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:49350–49358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greene LA, Angelastro JM. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:1347–1352. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-8807-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ott CM, Lingappa VR. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:2003–2009. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.10.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torres J, Stevens TJ, Samsó M. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:137–144. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speers AE, Wu CC. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3687–3714. doi: 10.1021/cr068286z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrinovic MM, Duncan CS, Bourikas D, Weinman O, Montani L, Schroeter A, Maerki D, Sommer L, Stoeckli ET, Schwab ME. Development. 2010;137:2539–2550. doi: 10.1242/dev.048371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elias LJ, Saucier DM. Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Boston, Pearson: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett MK, Calakos N, Scheller RH. Science. 1992;257:255–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1321498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saegusa C, Fukuda M, Mikoshiba K. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24499–24505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owczarek S, Kiryushko D, Larsen MH, Kastrup JS, Gajhede M, Sandi C, Berezin V, Bock E, Soroka V. FASEB J. 2010;24:1139–1150. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-140509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smalla KH, Matthies H, Langnase K, Shabir S, Bockers TM, Wyneken U, Staak S, Krug M, Beesley PW, Gundelfinger ED. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4327–4332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080389297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bejanin S, Cervini R, Mallet J, Berrard S. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:21944–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alder J, Thakker-Varia S, Bangasser DA, Kuroiwa M, Plummer MR, Shors TJ, Black IB. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:10800–10808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10800.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu G, Sun L, Yan XJ, Dovichi NJ. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:2569–2573. doi: 10.1021/ac303750g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuberovic A, Wetterhall M, Hanrieder J, Bergquist J. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:1836–1843. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Zhang Y, Xiang F, Zhang Z, Li L. J. Chromatogr. A. 2010;1217:4463–4470. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z, Ye H, Wang J, Hui L, Li L. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:7684–7691. doi: 10.1021/ac300628s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Ye H, Zhang Z, Xiang F, Girdaukas G, Li L. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:3462–3469. doi: 10.1021/ac200708f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanrieder J, Nyakas A, Naessén T, Bergquist J. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:443–449. doi: 10.1021/pr070277z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang H, Kachman MT, Schwartz DR, Cho KR, Lubman DM. Proteomics. 2004;4:2476–2495. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bączek T. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2004;35:895–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Rudnick PA, Evans EL, Li J, Zhuang Z, DeVoe DL, Lee CS, Balgley BM. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6549–6556. doi: 10.1021/ac050491b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.