Abstract

Objective

To examine the reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) in a large observational cohort of persons with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

We evaluated the reliability of the SLAQ using Cronbach's alpha and principal factor analysis and ascertained construct validity by studying the association of the SLAQ with other clinically relevant, validated patient assessments of health. We estimated responsiveness by calculating standardized response means and analyzing the association of changes in SLAQ scores with changes in other patient assessments of health.

Results

The SLAQ had excellent reliability, as reflected by Cronbach's alpha (0.87) and principal factor analysis (one factor accounted for 92% of the variance). SLAQ scores were strongly correlated with other health indices, including the Short Form 12 Physical Component Summary and the Short Form 36 Physical Functioning subscale. Scores were significantly higher for respondents reporting a flare, more disease activity, hospitalization in the last year, concurrent use of immunosuppressive medication, and work disability. The SLAQ demonstrated a small to moderate degree of responsiveness; standardized response means were 0.66 and −0.37 for those reporting clinical worsening and improvement, respectively. Across a range of other patient assessments of disease status, the SLAQ had a response in the direction predicted by these other measures.

Conclusion

The SLAQ demonstrates adequate reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness in our large, community-based cohort and appears to represent a promising tool for studies of SLE outside the clinical setting.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex autoimmune disease characterized by involvement of multiple organ systems and the formation of autoantibodies. In the US, SLE has a prevalence of 1.2 per 1,000 persons and is more prominent in women and certain racial/ethnic minorities (1,2). A growing body of literature suggests greater disease activity and damage in certain segments of the population, including racial/ethnic minorities and individuals with lower socioeconomic status (3–7). As epidemiologic studies attempt to further explore the root causes for these and other observations, the need for instruments that measure disease status outside the clinical setting has arisen. For SLE, only one such instrument has been developed and validated to date: the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) (see Appendix A, available at the Arthritis Care & Research Web site at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0004-3591:1/suppmat/index.html) (8).

Traditional assessments of SLE disease activity, such as the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Measure (SLAM) (9), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) (10), British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) (11), and European Consensus Lupus Activity Measure (ECLAM) (12), rely on a physician-obtained history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation. For large epidemiologic studies in which many patients live outside the catchment area of an academic medical center, such physician-directed assessments may prove impractical and costly. To address these issues, Karlson et al (8) developed the SLAQ for use in situations where clinically based disease activity measures may be difficult to obtain. The SLAQ relies on patient self-report of disease activity across several domains contained in its clinical counterpart, the SLAM.

The SLAQ was developed in a clinical setting using assessments of 93 patients who presented to an academic medical center for clinical care. SLAQ scores were compared with contemporary SLAM scores (omitting laboratory items) and were found to correlate well with the systematic review of symptoms and physical examination performed by a rheumatologist (r = 0.62, P < 0.0001). Positive predictive values for the SLAQ ranged from 56% to 89% for detecting clinically significant disease activity (8).

Although several research groups are now using the SLAQ in a range of clinical and epidemiologic studies (13–16), no further validation studies of the measure have been completed to date. Furthermore, little is known about the acceptability, reliability, construct validity, or responsiveness of this instrument in a community-based sample. We sought to examine these aspects of the SLAQ using the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Lupus Outcomes Study (LOS), a large observational cohort of individuals with SLE.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Data were derived from the UCSF LOS, an observational cohort of 982 English-speaking patients with SLE. Details regarding creation of the cohort have been described elsewhere (17) but relevant aspects will be summarized here. The cohort was assembled by reenrolling patients from a previous UCSF study of genetic factors in SLE. Patients were originally recruited from academic rheumatology offices (23%), community rheumatology offices (11%), and community-based sources (66%), such as SLE support groups, the Internet, and media advertisements. Patients who had completed enrollment for the genetics study between 1997 and 2002 were asked to participate in the LOS, which involved an annual structured telephone interview and updates of their medical records. Diagnoses of SLE were confirmed after chart review by either a rheumatologist or registered nurse working under a rheumatologist's supervision. Of participants in the genetics study, 83% of those eligible for the LOS were successfully contacted, and 78% of those reached agreed to participate between 2002 and 2003.

The LOS introduced the SLAQ in the second interview year; therefore, we drew data for the current study from the second and third consecutive years of the study. A total of 832 respondents completed the interview in the second year, and 764 were reinterviewed in the subsequent year (8 deaths; attrition rate ∼7.3%). SLAQ scores were obtained for 830 participants in the second interview year and for 760 of those reinterviewed in the following year. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved the study protocol.

Data collection

Trained interviewers administered an hour-long telephone survey to participants, eliciting information about their demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, medications, disability, general health and social functioning, health care utilization, health insurance coverage, and measures of disease status, including the SLAQ.

Measures

The SLAQ is based on items from the SLAM that are amenable to self-report and includes 24 questions related to disease activity: weight loss, fatigue, fevers, oral ulcers, malar rash, photosensitivity, vasculitis, other rashes, alopecia, lymphadenopathy, dyspnea, chest pain, Raynaud's phenomenon, abdominal pain, paresthesias, seizures, stroke, memory loss, depression, headaches, myalgias, muscle weakness, arthralgias, and joint swelling. Items are weighted and aggregated in a manner analogous to the scoring system used in the SLAM, and scores can range from 0 to 44.

Several other patient assessments of disease activity and health status were used in the study. We used the Short Form 12 (SF-12) Global Health Rating and Physical Component Score (18) and the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Physical Functioning subscale (19) as measures of overall health status. Patient assessment of disease activity was evaluated using 2 questions. The first question, “In the past 3 months, have you had a lupus flare?” (patient global assessment of flare), was dichotomized by respondents who did or did not report a disease flare. Respondents were subsequently asked if the flare was mild, moderate, or severe. The second question, “Please rate the activity of your lupus during the past three months,” (patient global assessment of disease activity), yielded a score from 0 to 10, with 10 representing the greatest disease activity. We also examined the Valued Life Activities index, a validated measure of functioning in discretionary life activities, such as visiting with friends or driving (20). In addition, patient-reported information was collected on certain disease manifestations, such as the presence of renal or pulmonary disease, as well as on hospitalizations. Medication use was also examined, comparing respondents who reported current use of an immunosuppressant (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, steroids, chlorambucil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, leflunomide, or a biologic agent) with those who did not report use of these drugs.

Finally, we looked at the relationship between SLAQ scores and work disability using questions from the US Census Bureau's Current Population Survey (21). Respondents were divided into those identified as employed (working, doing any work in the last week for pay or profit, or having a job but not working) and all others (looking for work, unable to work, keeping house, going to school, retired). Among patients not currently employed, we further examined SLAQ scores in those reporting inability to work.

Statistical analysis

Acceptability and distribution

We performed a series of cross-sectional analyses using data from the second interview year. First, we examined response rates for individual SLAQ items as a proxy for the scale's acceptability. Next, we examined the distribution of SLAQ scores using the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality as well as a normal-quantile plot. Finally, univariate linear regression was used to investigate the relationship of various demographic and disease characteristics (including age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, education, disease duration, and the presence of renal disease or lung disease) with SLAQ scores. Multivariate linear regression, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, education, and disease duration, was subsequently used to further examine SLAQ scores in different groups.

Reliability

internal consistency

To examine the SLAQ's reliability and internal consistency, we first calculated Cronbach's alpha (22). Next, we analyzed the relationship among variables in the SLAQ using principal factor analysis. A maximum likelihood ratio test was used to examine the goodness-of-fit of the identified factor structure.

Construct validity

Again using data from the second interview year, we examined a variety of disease-related outcomes and patient assessments to assess the construct validity of the SLAQ (22). First, patient and disease characteristics, stratified by SLAQ scores, were examined using univariate linear regression. Next, we examined the association between SLAQ scores and dichotomous outcomes, including patient global assessment of flare, work disability, hospitalization in the previous year, and use of immunosuppressive medications using Student's t-tests. The association between SLAQ scores and patient assessment of flare severity was examined using analysis of variance. Finally, we examined the association between SLAQ scores and continuous outcomes, including patient global assessment of disease activity (0–10 scale), SF-12 Global Health Rating, SF-12 Physical Component Summary, and SF-36 Physical Functioning subscale, using Spearman's correlation coefficient and the accompanying test of significance.

Responsiveness

We evaluated the responsiveness of the SLAQ over 2 years of the study. Although several responsiveness indices have been described (23), we used 2 well-described methods in this study: the standardized response mean and the relationship of changes in the SLAQ over time with changes in other patient assessments of health status. The standardized response mean is among the most commonly used indices of responsiveness and is calculated by dividing the mean change in scores by the standard deviation of this change. We calculated the overall standardized response mean for the SLAQ over 2 consecutive interview years. This global mean, however, likely underestimates responsiveness from a group of patients in which some have decreased disease activity while others have increased disease activity. To address this concern, we examined standardized response means among patients who described clinical improvement, no change, or clinical worsening (as defined by a change of ±0.5 SD in patient global assessment of disease activity) (24).

To compare the SLAQ with other patient assessments of health status, we used 0.5 SDs of the baseline score on the various measures to indicate clinically significant change in the subsequent year. This cut point represents a conservative estimate of the minimally clinically important difference for a wide variety of patient assessment instruments (24). For SLAQ score, the cut point was 3.99 points; for SF-12 Physical Component Summary, 3.23 points; for SF-36 Physical Functioning score, 14.9 points; for patient global assessment of disease activity, 1.37 points; and for Valued Life Activities index, 0.29 points (the latter representing the mean difficulty with activities on a 0–3 scale). Respondents were grouped into 3 categories using this change threshold: those who reported significant worsening, those who remained approximately the same, and those who improved. We calculated mean change in SLAQ scores for respondents who worsened, stayed the same, or improved on the examined measure. Lastly, the correlation between the change in the various measures examined and the change in SLAQ score was calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were completed using STATA software, version 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Acceptability and distribution

The acceptability of the SLAQ for LOS respondents was high, with a majority of items having >99% response rate. One item had no missing responses (weight loss) and several had only 1 missing response (oral ulcers, malar rash, dyspnea, memory loss, and arthralgias). The 2 items with the largest nonresponse rate were a question pertaining to vasculitis (9 missing responses or 1.1% of the sample) and a question pertaining to Raynaud's phenomenon (6 missing responses or 0.7% of the sample). Given the high response rate, additional analysis to examine relationships between nonresponse and demographic characteristics of interest (e.g., educational attainment) was not indicated.

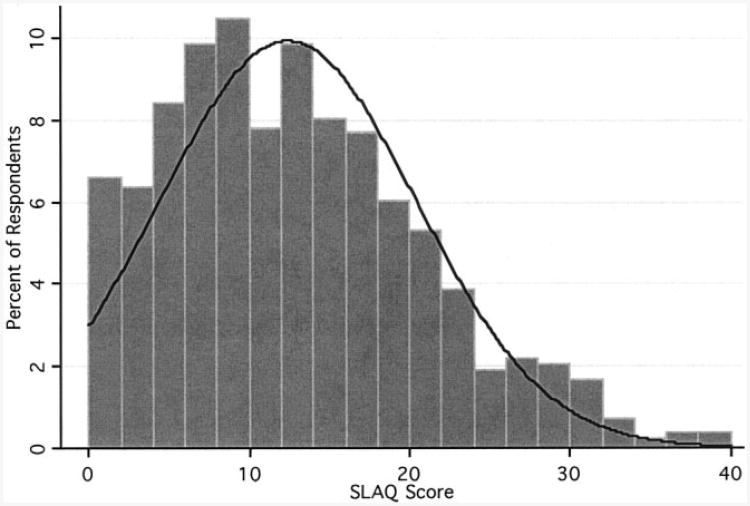

SLAQ scores were fairly normally distributed in the LOS, although a slight rightward skew was noted, with 0.9% of the sample having scores >35 (Figure 1). Using the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality, we tested the null hypothesis that SLAQ scores came from a normally distributed population (P < 0.0001); results suggested that the distribution did deviate from normality. A normal-quantile plot (not shown) confirmed that the 2 extremes in the distribution of SLAQ scores in the LOS varied slightly from the normal distribution.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) scores in 830 participants in the Lupus Outcomes Study. Shapiro-Wilk test of normality. W = 0.97 (P < 0.0001).

The demographic and disease characteristics of LOS respondents by SLAQ scores are listed in Table 1. Scores were lowest for patients <30 years of age compared with other age categories and were significantly lower for men. SLAQ scores were higher for African American respondents than for white respondents, although this result did not reach statistical significance, and were significantly lower for Asian/Pacific Islander respondents. Income was inversely related to SLAQ scores. A similar relationship was observed for education: participants with lower educational attainment reported significantly more disease activity. Interestingly, disease duration was unrelated to SLAQ scores in our sample. Although the magnitude of these relationships changed somewhat after multivariate adjustment (age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, education, and disease duration were included in the model), the direction of the findings remained the same; younger patients, men, Asian/Pacific Islanders, those with higher incomes, and those with higher educational attainment had lower SLAQ scores (data not shown). Finally, certain self-reported disease manifestations, such as the presence of renal or pulmonary disease, were associated with higher SLAQ scores.

Table 1. Demographic and disease characteristics of the 830 respondents from the Lupus Outcomes Study by SLAQ scores*.

| Characteristics | Number (n = 830) | SLAQ score, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| <30 | 74 | 8.2 ± 7.2 |

| 31–40 | 153 | 11.3 ± 7.6† |

| 41–50 | 246 | 14.1 ± 8.4† |

| 51–64 | 271 | 12.6 ± 8.0† |

| ≥65 | 86 | 12.5 ± 7.1† |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 62 | 8.20 ± 6.46 |

| Female | 768 | 12.8 ± 8.04† |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 590 | 12.7 ± 7.9 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 64 | 11.9 ± 8.0 |

| African American | 58 | 13.2 ± 7.3 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 72 | 8.2 ± 7.2† |

| Other | 46 | 14.2 ± 9.7 |

| Income per year | ||

| $0–$20,000 | 132 | 15.3 ± 8.9 |

| $20,000–$40,000 | 162 | 14.4 ± 8.2 |

| $40,000–$60,000 | 144 | 12.7 ± 7.8‡ |

| $60,000–$80,000 | 126 | 11.6 ± 6.7‡ |

| $80,000–$100,000 | 86 | 10.4 ± 7.4‡ |

| >$100,000 | 138 | 9.4 ± 6.8‡ |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 120 | 14.8 ± 9.1 |

| Some college/vocational | 392 | 13.8 ± 7.9 |

| Bachelor's degree | 184 | 9.7 ± 7.1† |

| Postgraduate | 133 | 10.1 ± 6.7† |

| Disease duration, years | ||

| <5 | 101 | 11.8 ± 8.1 |

| 6–10 | 284 | 13.5 ± 7.6 |

| 11–15 | 170 | 12.9 ± 8.8 |

| 16–20 | 116 | 11.4 ± 6.8 |

| ≥21 | 159 | 11.1 ± 8.4 |

| Renal disease | ||

| Present | 171 | 15.2 ± 9.0 |

| Absent | 644 | 11.6 ± 7.6† |

| Lung disease | ||

| Present | 169 | 18.7 ± 7.7 |

| Absent | 645 | 10.7 ± 7.2† |

Analysis using univariate linear regression. SLAQ = Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire.

P < 0.0001 compared with reference group.

P < 0.01 compared with reference group.

Reliability: internal consistency and data structure

The SLAQ demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87. Data structure was further examined using principal factor analysis (results not shown). The extraction of factors yielded only 1 eigenvalue >1.0, which accounted for 92.3% of the variance, and implied that SLAQ items test 1 overall construct. We used a likelihood ratio test to examine the goodness-of-fit of this factor structure, and results (χ2 = 3922.7, P < 0.0001) were indicative of good explanatory power.

Construct validity

To ascertain construct validity, we examined the correlation of the SLAQ with measures that are likely to be related to disease activity in SLE (Table 2) (22). As expected, SLAQ scores were significantly higher for respondents who reported an SLE flare in the last 3 months, and a graded effect was noted by the self-reported severity of the flare. Similarly, there was a strong correlation between patient global assessment of disease activity and SLAQ scores.

Table 2. Association between SLAQ score and patient health assessments, hospitalizations, and medications in the Lupus Outcomes Study*.

| Characteristic | No. | SLAQ score, mean ± SD | P† | Correlation (r) with SLAQ score‡ | P‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| SLAQ total | 830 | 12.4 ± 8.0 | |||

| Patient global assessment of flare | |||||

| Reported flare | 380 | 17.0 ± 7.3 | <0.0001 | ||

| No flare | 424 | 8.3 ± 6.3 | |||

| Patient assessment of flare severity | |||||

| Mild | 123 | 13.1 ± 6.0 | |||

| Moderate | 152 | 17.0 ± 6.2 | <0.0001 | ||

| Severe | 105 | 21.4 ± 7.6 | |||

| Employment and work disability | |||||

| Employed | 382 | 9.7 ± 6.6 | |||

| Not employed | 448 | 14.7 ± 8.4 | <0.0001 | ||

| Unable to work | 267 | 17.2 ± 8.1 | <0.0001 | ||

| Hospitalization in last year | |||||

| Yes | 176 | 14.9 ± 8.5 | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 650 | 11.6 ± 7.6 | |||

| Medication use | |||||

| Concurrent immunosuppressive§ | 427 | 13.1 ± 8.5 | 0.02 | ||

| On hydroxychloroquine, NSAIDs, or other nonimmunosuppressive | 403 | 11.7 ± 7.4 | |||

| Other patient assessments | |||||

| Patient global assessment of disease | 824 | 0.73 | <0.0001 | ||

| activity (0–10 scale) | |||||

| SF-12 Global Health Rating | 763 | 0.65 | <0.0001 | ||

| SF-12 Physical Component Summary | 803 | 0.51 | <0.0001 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Functioning Subscale | 830 | 0.66 | <0.0001 | ||

SLAQ = Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; SF-12 = Short Form 12; SF-36 = Short Form 36.

Student's t-test or analysis of variance where appropriate.

Spearman's correlation coefficient and test of significance.

Including current use of mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, steroids, chlorambucil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, leflunomide, or biologic agent.

General measures of health status, including the SF-12 Global Health Rating, SF-12 Physical Component Summary, and the SF-36 Physical Functioning subscale, were all highly correlated with SLAQ scores. Significant differences in SLAQ scores were also noted for respondents who reported work disability, hospitalization in the last year, and use of immunosuppressive medications.

Responsiveness

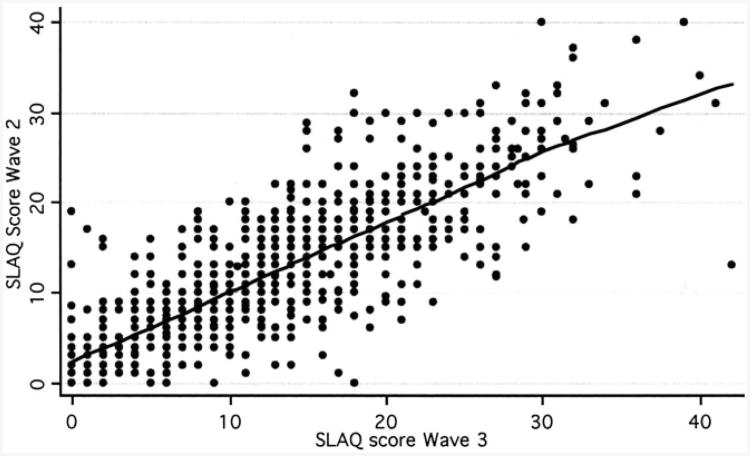

As expected, SLAQ scores were highly correlated between consecutive interview years (Figure 2). The overall standardized response mean was 0.12; using Cohen's interpretation of effect sizes, this would represent minimal responsiveness (25). When SLAQ scores were stratified by changes in patient global assessment of disease activity, standardized response means were as follows: clinical worsening, 0.66; no change, 0.10; and improvement, −0.37. These results suggest a small to moderate degree of responsiveness for participants who reported a perceived change in disease status.

Figure 2.

Correlation between Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) scores in years 2 and 3 of the Lupus Outcomes Study. r = 0.81 for correlation between consecutive SLAQ scores, using Spearman's correlation coefficient. Weighted regression line reflects lowess smoother.

We further examined the responsiveness of the SLAQ by analyzing the association of changes in SLAQ scores over time with other clinically relevant, validated patient assessments of health (26). Of the 760 participants consecutively interviewed over 2 years who had SLAQ scores, 180 had a higher SLAQ score (more disease activity as defined by an increase of >0.5 SDs in SLAQ score), 446 reported no change, and 132 reported a lower SLAQ score (less disease activity as defined by a decrease of >0.5 SDs in SLAQ score) (Table 3). SLAQ scores changed in the direction predicted by most of the other measures examined, including the SF-36 Physical Functioning score, patient global health rating, and Valued Life Activities index. The exception was the SF-12 Physical Component Summary, for which SLAQ scores remained slightly higher for participants reporting improvement on this measure.

Table 3. Responsiveness of SLAQ over time and comparison with other patient assessments in 760 respondents from the Lupus Outcomes Study*.

| Change in score on examined instrument | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Patient assessment instruments | Worse (0.5 SDs) | No change | Improved (0.5 SDs) | P† |

|

| ||||

| SLAQ | 180 | 446 | 132 | |

| Change in SLAQ score | 7.05 ± 3.5 | 0.16 ± 1.8 | −6.78 ± 2.8 | – |

| SF-12 (PCS) | 187 | 315 | 214 | |

| Change in SLAQ score | 1.30 ± 5.0 | 0.52 ± 4.8 | 0.05 ± 5.2 | 0.04 |

| SF-36 Physical Functioning | 145 | 468 | 144 | |

| Change in SLAQ score | 3.61 ± 5.5 | 0.06 ± 4.6 | −0.71 ± 5.1 | <0.0001 |

| Patient global assessment of disease activity (0–10) | 158 | 440 | 153 | |

| Change in SLAQ score | 3.49 ± 5.3 | 0.42 ± 4.3 | −2.01 ± 5.4 | <0.0001 |

| Valued Life Activities | 102 | 486 | 123 | |

| Change in SLAQ score | 3.45 ± 5.3 | 0.51 ± 4.7 | −1.04 ± 5.2 | <0.0001 |

Values are the number or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. PCS = Physical Component Summary; see Table 2 for additional definitions.

P value associated with correlation between change in SLAQ score and change in examined measure.

Discussion

Extending scientific research outside the clinical setting in SLE remains a challenging task. The relative rarity and complexity of the disease remain barriers for population studies, as do the lack of suitable case findings and disease assessment tools. Although measures of general health, such as the SF-36, provide some insight into disease status in epidemiologic studies, more specific tools have the potential to better represent health-related outcomes. The development and validation of patient-reported instruments such as the SLAQ hold promise in addressing this gap.

The SLAQ was originally developed to provide an economical way of tracking disease activity for large studies in SLE. In a group of patients presenting for clinical care, the SLAQ correlated well with a systematic review of symptoms and physical examination performed by a rheumatologist (8). In the present study, we sought to expand this initial validation study on several fronts: first, by examining the performance of the SLAQ in a communitybased cohort of persons with SLE, and second, by studying the psychometric properties of the SLAQ, including its reliability and validity. Validity has emerged as a multifaceted concept in the literature, and conclusions about its fundamental components vary. However, common notions in most models include the ideas of face validity, criterion validity, construct validity, and, more recently, responsiveness. Criterion validity was assumed based on the original SLAQ validation study; we examined each of the other components of validity for the instrument as well as its reliability.

As an aggregate measure of disease activity in SLE, the SLAQ has reasonable face validity. First, SLAQ items closely emulate the instrument's widely used clinical counterpart, the SLAM. Although likely to lose some degree of accuracy because of the omission of laboratory items, the SLAQ contains most clinical components of an SLE flare. Second, the SLAQ had extremely high response rates for all items among LOS participants, even in the 14% reporting lower educational attainment (a high school education or less). This finding suggests that the instrument has adequate acceptability. Third, as expected in a community-dwelling population with SLE, a range of SLAQ scores were observed, approximating a normal distribution but with a rightward skew (Figure 1). The appearance of the distribution is similar to previous reports of the SLAM's distribution in clinical studies (9). Finally, administration of the SLAQ in consecutive years yielded strongly correlated scores, supporting the instrument's reproducibility (Figure 2).

Calculation of Cronbach's alpha and principal factor analysis were used to examine the reliability of the SLAQ. The results indicate that SLAQ items are highly correlated, suggesting that the instrument relates to a single construct. The finding of only 1 factor in the analysis precluded creation of meaningful subscales for the SLAQ.

We used several approaches to determine the construct validity of the SLAQ. The first entailed examining the distribution of SLAQ scores among subgroups in the LOS. We found that the distribution of SLAQ scores across socioeconomic groups in the LOS paralleled findings of previous studies. Similar to the LUpus in MInorities, NAture versus nurture (LUMINA) study, we found increased disease activity in individuals with lower incomes and lower educational attainment (27,28). However, other findings were somewhat less consistent with previous literature. The youngest age group (<30 years) had the lowest SLAQ scores in our cohort, and scores peaked in the 41-50 age group. Other studies suggest that disease activity declines with age (27). Similarly, women reported significantly more disease activity than men, whereas previous literature suggests similar levels of disease activity in women and men (29,30). It remains unclear whether these findings reflect the true distribution of disease activity in our cohort, or whether individuals in these demographic groups have different response profiles to SLAQ items. As expected, African Americans had higher SLAQ scores in the LOS. However, Hispanic/Latinos had scores similar to whites, and Asian/Pacific Islanders had significantly lower scores. This may reflect underrepresentation of ethnic minorities with more severe disease in our sample. Alternatively, these results raise the question of whether the SLAQ requires further validation in these demographic groups.

To further ascertain the construct validity of the SLAQ, we compared SLAQ scores with other assessments relating to the overall construct of health status. SLAQ scores were strongly correlated with most other indices, including the SF-12 Global Health Rating, the SF-12 Physical Component Summary, and the SF-36 Physical Functioning subscale. SLAQ scores were significantly higher for respondents reporting a flare, more disease activity, hospitalization in the last year, concurrent use of immunosuppressive medication, and work disability.

Responsiveness has more recently emerged as an important concept when examining health measurement tools and refers to the ability of an instrument to detect important changes in health. The overall standardized response mean for the SLAQ was low (0.12) in our cohort. However, given that patients did not undergo a specific effective treatment that would lead to improvement between consecutive interviews, it is likely that this mean underestimates the responsiveness of the SLAQ (31). When stratified by patient global assessments of change in disease activity, the standardized response means obtained were comparable with those of other commonly used measures of disease activity in SLE (0.66 for clinical worsening, −0.37 for improvement), such as the SLEDAI and SLAM (32). Interestingly, the standardized response mean for clinical worsening was greater than for improvement. Although the reasons for this require further investigation, some hypotheses include that the SLAQ better detects disease flares than improvements, or that flares procure decrements in health status that are larger than the positive changes induced by improvements.

In addition, the SLAQ demonstrated a response in the direction predicted by other patient assessments of disease status, including the patient global assessment of disease activity, the SF-36 Physical Functioning subscale, and the Valued Life Activities index. The exception was the SF-12 Physical Component Summary, where respondents who reported worsening physical function actually had slight improvements in SLAQ scores. The reasons for this latter finding remain unclear; possible explanations may include lack of specificity of the SF-12 Physical Component Summary compared with the SF-36 Physical Functioning subscale, the higher responsiveness of the SF-36 in our cohort, or the possibility that the SLAQ is a more global assessment of SLE activity, whereas the SF-12 Physical Component Summary may more specifically reflect musculoskeletal functioning.

This study has several important limitations. Although two-thirds of the patients in our cohort were originally recruited from outside the clinical setting, respondents are likely to have higher educational attainment and increased access to care compared with the general population of patients with SLE in the US. This may have influenced the high response rate to SLAQ items in our study. Second, we lacked a gold standard for change in disease activity, such as a rheumatologist-assessed disease activity index. Many of the participants in our study reported care only by generalists, and among those reporting specialty care, timely medical record review would have been hampered by a low likelihood of a physician visit contemporary with their interview date for the LOS. Moreover, retrospective assessment of the SLAM through chart review may have poor reliability (33). Lastly, SLAQ scores reflect disease activity over the previous 3 months, and therefore responsiveness would more ideally be analyzed on SLAQ scores obtained quarterly. Because the LOS surveys participants yearly, our analysis may have decreased precision. Future studies are therefore needed to confirm the reliability of the SLAQ compared with a physician assessment, particularly in different age, sex, and racial/ethnic groups.

In conclusion, the SLAQ demonstrates adequate reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness in our large, community-based cohort of persons with SLE. Although further studies are needed to verify its reliability and to document its psychometric properties in populations with lower literacy or poorer access to health care, the SLAQ appears to represent a promising tool for studies of SLE outside the clinical setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Because Drs. Yelin and Katz are Editors of Arthritis Care & Research, review of this article was handled by the Editor of Arthritis & Rheumatism.

Supported in part by the General Clinical Research Center, Moffit Hospital, University of California, San Francisco, United States Public Health Service, by the Rosalind Russell Medical Research Center for Arthritis, and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (5-M01-RR-00079). Dr. Yazdany received an American College of Rheumatology/Research and Education Foundation Physician Scientist Development Award. Dr. Yelin's work was supported by the State of California Lupus Fund, Arthritis Foundation, and a grant from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (1-R01-HS013893).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Yazdany had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study design. Yazdany, Yelin, Katz.

Acquisition of data. Yelin, Trupin.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Yazdany, Yelin, Panopalis, Trupin, Katz.

Manuscript preparation. Yazdany, Yelin, Panopalis, Julian, Katz.

Statistical analysis. Yazdany.

References

- 1.Uramoto KM, Michet CJ, Jr, Thumboo J, Sunku J, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Trends in the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus, 1950–1992. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:46–50. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<46::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA, Jr, Ramsey-Goldman R, LaPorte RE, Kwoh CK. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus: race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260–70. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odutola J, Ward MM. Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health among patients with rheumatic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:147–52. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000151403.18651.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutcliffe N, Clarke AE, Gordon C, Farewell V, Isenberg DA. The association of socioeconomic status, race, psychosocial factors and outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:1130–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotstein DS, Ward MM, Bush TM, Lambert RE, van Vollenhoven R, Neuwett CM. Socioeconomic status and health in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1720–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Lew RA, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, Fossel AH, et al. The relationship of socioeconomic status, race, and modifiable risk factors to outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:47–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bartolucci AA, Roseman J, Lisse J, Fessler BJ, et al. LUMINA Study Group. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. IX. Differences in damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2797–806. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2797::aid-art467>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Rivest C, Ramsey-Goldman R, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, et al. Validation of a Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) for population studies. Lupus. 2003;12:280–6. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu332oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang MH, Socher SA, Larson MG, Schur PH. Reliability and validity of six systems for the clinical assessment of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1107–18. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang DH Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Derivation of the SLEDAI: a disease activity index for lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symmons DP, Coppock JS, Bacon PA, Bresnihan B, Isenberg DA, Maddison P, et al. Members of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) Development and assessment of a computerized index of clinical disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Q J Med. 1988;69:927–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitali C, Bencivelli W, Isenberg DA, Smolen JS, Snaith ML, Scuito M, et al. The European Consensus Study Group for Disease Activity in SLE. Disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: report of the Consensus Study Group of the European Workshop for Rheumatology Research. II. Identification of the variables indicative of disease activity and their use in the development of an activity score. Clin Exp Rheu-matol. 1992;10:541–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costenbader KH, Karlson EW, Gall V, de Pablo P, Finckh A, Lynch M, et al. Barriers to a trial of atherosclerosis prevention in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:718–23. doi: 10.1002/art.21441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C, Almagor O, Dunlop DD, Manzi S, Spies S, Chadha AB, et al. Disease damage and low bone mineral density: an analysis of women with systemic lupus erythematosus ever and never receiving corticosteroids. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:53–60. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazdany J, Gillis JZ, Panopalis P, Julian L, Katz P, Yelin E. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence and treatment of major depressive disorder in a large observational cohort of persons with systemic lupus erythematosus [abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):S274–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz R, Petri M, Karlson EW, Alarcon GS, Chakravarty E, Goldman J, et al. Performance of the SLAQ in SLE and non-SLE subjects in a longitudinal databank [abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):S733. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yelin E, Trupin L, Katz P, Criswell L, Yazdany J, Gillis J, et al. Work dynamics among persons with systemic lupus erythem-atosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:56–63. doi: 10.1002/art.22481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;32:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston (MA): The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz PP, Morris A, Yelin EH. Prevalence and predictors of disability in valued life activities among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:763–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Bureau of the Census. Current population survey technical documentation. Washington (DC): US Department of Commerce; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunnally J, Berstein IH. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright JG, Young NL. A comparison of different indices of responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:239–46. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;41:582–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corzillius M, Fortin P, Stucki G. Responsiveness and sensitivity to change of SLE disease activity measures. Lupus. 1999;8:655–9. doi: 10.1191/096120399680411416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alarcon GS, Calvo-Alen J, McGwin G, Uribe AG, Toloza SM, Roseman JM, et al. LUMINA Study Group. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic cohort: LUMINA XXXV. Predictive factors of high disease activity over time. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1168–74. doi: 10.1136/ard.200X.046896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alarcon GS, Roseman J, Bartolucci AA, Friedman AW, Moulds JM, Goel N, et al. LUMINA Study Group. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. II. Features predictive of disease activity early in its course. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1173–80. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1173::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrade RM, Alarcon GS, Fernandez M, Apte M, Vila LM, Reveille JD LUMINA Study Group. Accelerated damage accrual among men with systemic lupus erythematosus. XLIV. Results from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:622–30. doi: 10.1002/art.22375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MH, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Killinger DW. Systemic lupus erythematosus in males. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62:327–34. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fortin PR, Abrahamowicz M, Clarke AE, Neville C, Du Berger R, Fraenkel L, et al. Do lupus disease activity measures detect clinically important change? J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang E, Abrahamowicz M, Ferland D, Fortin PR CaNIOS Investigators. Comparison of the responsiveness of lupus disease activity measures to changes in systemic lupus erythematosus activity relevant to patients and physicians. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:488–97. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wluka AE, Liang MH, Partridge AJ, Fossel AH, Wright EA, Lew RA, et al. Assessment of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity by medical record review compared with direct standardized evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:57–61. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.