Abstract

Few antimicrobial drugs function by directly targeting RNA. A small molecule that binds the hepatitis C viral genome by ‘locking’ in a particular RNA conformation to inhibit viral protein production suggests a new paradigm for drug design.

Over 3% of the world population is infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV)1. There is no vaccine for this, and the best treatment available (interferon-ribavirin combination) is effective in fewer than half of patients. Several drug candidates are currently in clinical trials that inhibit the virally encoded HCV protease, a classical target for intervention. However, this member of the Flaviviridae virus family is prone to frequent mutation, making the development of prophylactic and curative treatment options with sustained efficacy particularly challenging. Interestingly, some of the most highly conserved regions of the HCV genome are found in untranslated regions. The HCV virus encodes an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) at the 5′ end of its genomic RNA that is responsible for initiation of protein synthesis. A small molecule recently discovered at Ibis Therapeutics binds a critical structure within the HCV IRES and inhibits its function2, and a study in this issue reveals its mechanism of inhibition. The benzimidazole derivative locks the RNA conformation and prevents the IRES from assuming its functional structure during initiation of protein synthesis. Viral replication studies by Parsons et al. suggest that this molecule may represent a new class of antivirals that function by directly binding to viral RNA3.

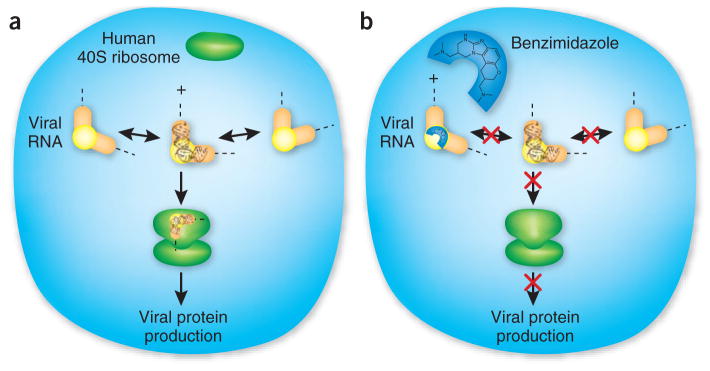

IRESs are highly structured RNA elements present in the genome of many retroviruses (and a few cellular genes) that control the initiation of protein synthesis. The HCV IRES directly interacts with the host 40S ribosomal subunit and helps recruit eukaryotic translational initiation factors4. This mechanism bypasses the canonical protein synthesis pathway, which depends on the recognition of the 5′ and 3′ ends of mature cellular mRNAs. Although the HCV IRES adopts conserved secondary and tertiary structures, like many other RNAs it retains conformational flexibility to recognize and adapt to various cellular targets (Fig. 1). By monitoring the distance between fluorescent tags on a viral RNA construct, Parsons et al. show that the benzimidazole derivative discovered at Ibis captures a specific structure within the HCV IRES domain, locking it into a conformation that is unable to interact productively with the host translation machinery (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Subdomain IIa of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) IRES (orange-yellow) forms an L-shaped structure that adopts multiple conformations due to intrinsic flexibility within the internal loop ‘elbow’. (a) The 40S human ribosome (green) recognizes the HCV IRES, with subdomain IIa inducing a conformational change required for initiation of viral protein synthesis. (b) Binding of a benzimidazole derivative (cyan) to the ‘elbow’ structure captures a single conformation of the IIa subdomain, which prevents mutual conformational adaptation with the assembling ribosome. Locking in this structure leads to decreased viral protein production, both in vitro and in infected cells. Crystal structure of subdomain IIa (black) adapted from ref. 7 (PDB ID: 2nok).

Subdomain IIa of the HCV IRES adopts an L shape and induces significant conformational changes in the 40S ribosomal subunit when it binds5–7. The benzimidazole derivative analyzed by Parsons et al. binds to the ‘elbow’ of subdomain IIa, and in doing so it fixes the interhelical angle at a conformation similar to that induced by a single A→U point mutation3. Both the benzimidazole derivative and the mutation reduce the production of viral proteins by approximately 80%, likely by preventing formation of the complete 80S eukaryotic ribosome. Hence this small molecule does not function by competitively inhibiting the interaction between the IRES and its target. Instead, it affects IRES-driven viral protein synthesis by altering RNA conformational properties at a step where mutual adaptation between the IRES and its ribosomal target is required for activation.

In the decade-long search for small-molecule drugs that target RNA, the focus has often been on disrupting the interactions between RNA and proteins. As with protein–protein complexes, abrogating such interactions has proven very difficult. Proteins have large surface areas and typically slow ‘off’ rates, making the target site on either protein or RNA inaccessible to small-molecule inhibitors. The task is even more challenging when targeting functional RNAs because of their intrinsic molecular flexibility. The present work illustrates a much more attractive strategy that exploits this very property of RNA. Nature has already provided us with examples of this principle in the aminoglycosides—antibiotics that function by stabilizing a conformation of bacterial ribosomal RNA prone to misincorporation. By capturing one structural state, a small molecule can affect RNA conformational equilibria without having to compete with proteins for binding energy or steric access.

The essential roles of viral RNA regulatory elements from HCV, HIV, influenza and other viruses make them attractive drug targets, but this feature remains completely unexploited. These RNA sequences encode not just a defined functional structure but also the ability to direct conformational changes in response to ligand binding to form alternative structures that are equally essential. This property of RNA is found in structures as diverse as the HCV IRES, the HIV trans-activation response element, and bacterial riboswitches8–11. This combination of genetic rigidity (high sequence conservation) and structural flexibility (the need to change structure for function) could turn out to be the Achilles’ heel of RNA viruses. Small-molecule inhibitors, such as the benzimidazole inhibitor described in this study, suggest a new strategy for the development of candidate RNA-binding antivirals. For this to happen, it will be necessary to substantially improve their potency and specificity while creating pharmacological characteristics conducive to successful preclinical and clinical development. If this can be done, perhaps anti-infective drug discovery will have found a new gold mine.

Contributor Information

Darren W Begley, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Gabriele Varani, Email: varani@chem.washington.edu, Department of Chemistry and Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C Fact Sheet No 164. WHO; Geneva: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seth PP, et al. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7099–7102. doi: 10.1021/jm050815o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons J, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:823–825. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pestova TV, Shatsky IN, Fletcher SP, Jackson RJ, Hellen CU. Genes Dev. 1998;12:67–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim I, Lukavsky PJ, Puglisi JD. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9338–9339. doi: 10.1021/ja026647w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spahn CM, et al. Science. 2001;291:1959–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.1058409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dibrov SM, Johnston-Cox H, Weng YH, Hermann T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:226–229. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leulliot N, Varani G. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7947–7956. doi: 10.1021/bi010680y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson JR. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:834–837. doi: 10.1038/79575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q, Stelzer AC, Fisher CK, Al-Hashimi HM. Nature. 2007;450:1263–1267. doi: 10.1038/nature06389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]