Abstract

Explore how social factors influence sleep, especially sleep-related beliefs and behaviors. Sleep complaints, sleep hygiene behaviors, and beliefs about sleep were studied in 65 black/African American and white/European American women. Differences were found for snoring and discrepancy between sleep duration and need. Sleep behaviors differed across groups for napping, methods for coping with sleep difficulties, and nonsleep behaviors in bed. Beliefs also distinguished groups, with differences in motivation for sleep and beliefs about sleep being important for health and functioning. These findings have important public health implications in terms of developing effective sleep education interventions that include consideration of cultural aspects.

Keywords: insomnia, race/ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

Sleep, when viewed as a universal biological process, is thought to be regulated in a manner in keeping with the 2-process model1 and the reciprocal interaction models2 regarding cycling of rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM. That is, the timing, duration, and composition of sleep are determined by circadian, homeostatic, and neurophysiologic factors. Thus, psychosocial factors are rarely viewed as mediators or moderators of normal sleep.

On the other hand, sleep, when viewed in terms of pathology, frequently takes into account psychological and behavioral factors. This is especially true for sleep disorders that fall under the broad category of disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, such as insomnia. In this case, psychological factors such as worry and behavioral issues such as sleep extension are viewed as the primary mediators or moderators of sleep continuity disturbance.3–5

Interestingly, social and cultural factors are rarely conceptualized as relevant determinants for either normal sleep or abnormal sleep (ie, sleep disorders).6,7 Social and cultural factors play a role by not only dictating specific sleep-related behaviors but in developing attitudes and beliefs about sleep, which then translate into behaviors. For example, if one is taught that sleep is not important for health, that person would presumably be less likely to seek adequate sleep and more likely to seek other, more high-priority activities.

As we develop and test behavioral interventions that we design to be culturally sensitive8–10 and address sleep and health issues in the general population,11–17 a better understanding of not only typical sleep-related behaviors but beliefs and attitudes about sleep as they vary across groups is necessary.

In the present pilot study, sleep-related complaints, sleep hygiene practices, and beliefs and attitudes about sleep were explored in a sample of adult women. Differences between white/European American (hereafter, white) and black/African American (hereafter, black) participants were a focus, due to established differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension,18 which may be affected by poor sleep.17,19–22 Our hypotheses were that we would find differences between groups in: (1) sleep-related complaints, (2) sleep hygiene practices, and (3) beliefs consistent with sleep being a priority and important for health.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 119 subjects attended 4 workshops (described below), held at various community centers in West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Seventy-nine (66.4%) subjects elected to answer the questions, from which the present data were compiled; all those who started the questionnaire provided complete data. No data (including demographics) were collected on the individuals who declined to participate. Participants consisted of men and women from a diverse set of ethnicities, including black (N = 41), white (N = 32), and other (N = 6) individuals. Due to the lack of male participants (3 white, 5 black), the analyses were restricted to women (29 white, 36 black). The majority of these women were older (Table 1). The current analysis focuses only on the white and black participants since the number of Asian/Pacific Islander and other-race individuals is not sufficient for independent evaluation.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of White and Black Participants

| Variables | Whites | Blacks | Group Differences (Mann-Whitney U) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 63.69 | 72.11 | ||

| Standard deviation | 10.25 | 8.05 | ||

| Range | 46–85 | 56–88 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Did not finish high school | 6.3% | 16.7% | ||

| High school diploma or General Education Development | 6.9% | 52.8% | 197.5 | <.0005 |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 6.9% | 13.9% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 44.8% | 8.3% | ||

| Masters or doctoral degree | 34.5% | 8.3% | ||

| Income | ||||

| ≤$24 999 | 17.2% | 38.9% | ||

| $25 000-$49 999 | 51.7% | 38.9% | 351.5 | .14 |

| $50 000-$74 999 | 17.2% | 11.1% | ||

| $75 000-$99 999 | 3.4% | 2.8% | ||

| ≥$100 000 | 0.0% | 2.8% |

Materials

Participants participated in a focus group in which sleep and health were discussed. As part of this, all participants were given a questionnaire to evaluate their beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding sleep as well as information about sleep complaints. The questionnaire included a total of 74 items, though only 44 were included in the present analysis since they directly pertain to the issues of practices, attitudes, and beliefs about sleep. The questionnaire was grounded in health behavior theory (especially, health belief model,23 theory of reasoned action,24 and transtheoretical model25). Questionnaire items were then refined by gathering input from several experts in the field (researchers and clinicians), as well as nonacademic individuals from West Philadelphia. Further, the participants completed the questionnaires in an open forum, where they could ask the leader of the focus group any questions about any items. Because the scale measures beliefs, attitudes, and habitual practices, and no validated subjective or objective measures also measure these general domains, initial validation of this scale was performed in accordance with accepted guidelines using focus groups,26–28 with the exception that the focus groups were larger than guidelines generally recommend.

Questions included in the present analysis are included in Table 1 to 4, with the response choices for each question. Sleep need and sleep duration were both recoded as a score of 1 to 5 (<6 hours = 0 and >9 hours = 4). A new variable was computed by subtracting ([need] - [duration]). Thus, this new difference score had a range of –4 to +4, indicating the number of different categories and in what direction.

Procedure

A community participatory research model was used for study participant recruitment. Outreach to the community through community leaders allows for inclusion of individuals who may otherwise be excluded from traditional research due to lack of access or prior negative perceptions of research. Additionally, endorsement by community leaders can help to increase participation rates. Consistent with this goal, once a community representative expressed interest, workshop content and venue were established collaboratively. Once a community center was identified, that center spread word of the workshops through its membership, providing the date and time of the workshops. All workshops were led by the same individual (N. P. P. ) and were mixed in racial composition. Also, participants were able to ask clarifying questions about items on the questionnaire, and the leader simply clarified what the question meant to ask.

The workshop attendance was uncompensated. No exclusion criteria were applied. Verbal informed consent was obtained; it was explicitly stated that workshop attendance was completely voluntary and that deidentified data would be used for research purposes. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania.

The format of the workshop included an introduction, identifying the group facilitator and stating the goals of the session, including: (1) increase public awareness of sleep’s role in health and safety, (2) learn about public perception and attitudes about sleep using a questionnaire and focus group, (3) administer a questionnaire, (4) conduct additional discussions, (5) present sleep-related health information to the group, and (6) obtain feedback from participants. The data presented in this paper come from the questionnaire that was administered (the only aspect of the workshop that could be explored quantitatively).

Questionnaires containing the items explored in the present study were completed by participants at 4 workshops held at community centers in Philadelphia: Germantown Jewish Center (n = 28), Sunshine Community Center (n = 28), West Philadelphia Community Center (n = 21), and Ralston Center (n = 22). Workshops were held in a focus group format. As mentioned earlier, participants were able to ask the leader of the workshop questions while completing the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Since all questions were ordinal in nature (rather than continuous or interval), use of nonparametric methods allowed for analysis of data that preserved the discrete nature of the responses without making assumptions of linearity, as would be the case with continuous variables in traditional parametric analysis (ie, the difference between “strongly agree” and “agree” is not necessarily the same as the difference between the next 2 response options of “agree” and “unsure”). White and black groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. To control for type I error, familywise a level was maintained at p = .05 for each group of variables, using the Bonferonni method, with trends reported for P < .05. This approach balances the less-conservative familywise vs studywise α level, with the more conservative Bonferonni control. Although ideally analyses would be adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic factors, the nature of the question responses violates the assumptions of most other approaches, including ordinal regression. This was borne out by the fact that there were insufficient cell sizes for performing adjusted analyses for many items, (eg, no participants said they strongly disagree that falling asleep at the wheel is serious). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 17.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

A total of 41 black and 32 white women volunteered to complete the questionnaire. Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The groups were roughly equivalent for age (mean, whites, 64 years; black, 72 years). While the groups did not differ between income, there was a significant difference between groups for educational attainment, with white individuals more likely to be college-educated (whites, 79%; blacks, 17%).

Sleep Complaints

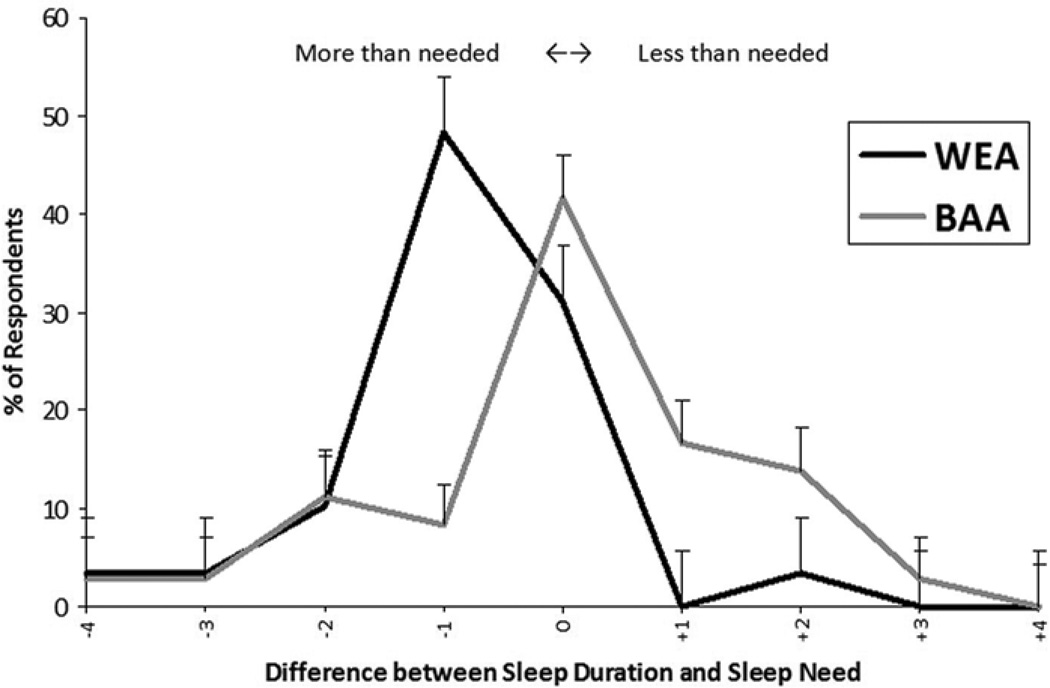

Rates of responses from both groups are reported in Table 2. Overall, there were no significant differences between groups for overall sleep quality and daytime sleepiness; however, snoring was endorsed more frequently in black participants. Also, no differences between overall habitual sleep duration or perceived sleep need were found; however, when the difference between sleep need and duration was computed, only 3.4% of white participants reported needing more sleep than they were experiencing, while 33.4% of black participants reported needing more sleep than they obtained (U = 408.0, p = .004). Values for both groups can be seen in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Sleep Complaints in White and Black Participants

| Variable | Whites, % | Blacks, % | Group Differences (Mann-Whitney U) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality | ||||

| 1 | 10.3 | 5.6 | ||

| 2 | 6.9 | 2.8 | ||

| 3 | 27.6 | 41.7 | ||

| 4 | 37.9 | 19.4 | ||

| 5 | 17.2 | 30.6 | 481.0 | .57 |

| Sleep duration, h | ||||

| <6 | 24.1 | 27.8 | ||

| 6–7 | 44.8 | 38.9 | ||

| 7–8 | 27.6 | 16.7 | ||

| 8–9 | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| >9 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 503.5 | .80 |

| Sleep need, h | ||||

| <6 | 6.9 | 19.4 | ||

| 6–7 | 20.7 | 36.1 | ||

| 7–8 | 55.2 | 19.4 | ||

| 8–9 | 13.8 | 19.4 | ||

| >9 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 423.0 | .17 |

| Daytime sleepiness | ||||

| Yes | 48.3 | 58.3 | ||

| No | 51.7 | 41.7 | 469.5 | .42 |

| Snoring | ||||

| Never | 72.4 | 38.9 | ||

| Once a month or less | 10.3 | 25.0 | ||

| Once a week or less | 10.3 | 8.3 | ||

| A few times a week | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Every night | 0.0 | 8.3 | 303.5 | .004 |

Figure 1.

Difference Between Reported Sleep Duration and Perceived Sleep Need in White and Black Participants

Numbers represent the difference in categories chosen. Negative numbers indicate that the participant reports greater sleep duration than need.

Sleep Hygiene

Rates of responses from both groups are reported in Table 3. Questions in this domain addressed: (1) what participants would do if they felt sleepy; (2) what participants would do if they were having difficulty falling asleep; and (3) activities that take place in bed on a regular basis, irrespective of whether they were sleepy or could not sleep. Regarding what participants would do if they were sleepy, groups were roughly equivalent in the likelihood that they would try to sleep better at night, drink caffeine, or exercise. Also, groups were not different in the likelihood that participants reported never feeling sleepy. The only difference was that black participants were more likely to take a nap during the day. If they were having difficulties falling asleep, both groups reported a roughly equal likelihood of staying in bed trying to sleep, getting up and doing something such as reading or watching television, and getting up to eat or drink something relaxing (such as warm milk) or caffeinated. Black participants, however, were more likely to endorse the following options: (1) stay in bed and do something such as read or watch television, (2) get up and drink alcohol, and (3) get up to start their day. Regarding activities that occur in bed, black participants were more likely to engage in activities other than sleeping, including reading or watching television, eating or drinking, worrying or thinking, and arguing or being angry. Groups were equally likely to do work in bed (which was rarely reported in both groups).

Table 3.

Sleep Hygiene in White and Black Participants

| Variable | Whites % |

Blacks % |

Group Differences (Mann-Whitney U) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How likely are you to try these options if you feel sleepy? | ||||

| Try to sleep better/sleep more at night | 438.0 | .56 | ||

| Very likely | 24.1 | 27.8 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 62.1 | 38.9 | ||

| Not very likely | 3.4 | 27.8 | ||

| Not likely at all | 6.9 | 0.0 | ||

| Nap during the day | 356.0 | .001 | ||

| Very likely | 10.3 | 25.0 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 27.6 | 58.3 | ||

| Not very likely | 44.8 | 11.1 | ||

| Not likely at all | 10.3 | 2.8 | ||

| Caffeine from coffee, tea, soda, or energy drinks | 417.0 | .48 | ||

| Very likely | 13.8 | 25.0 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 55.2 | 38.9 | ||

| Not very likely | 10.3 | 16.7 | ||

| Not likely at all | 17.2 | 11.1 | ||

| Exercise or other physical activity | 374.5 | .63 | ||

| Very likely | 17.2 | 22.2 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 41.4 | 33.3 | ||

| Not very likely | 13.8 | 22.2 | ||

| Not likely at all | 17.2 | 8.3 | ||

| I would never be sleepy | 357.5 | .08 | ||

| Very likely | 13.8 | 8.3 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 13.8 | 8.3 | ||

| Not very likely | 51.7 | 47.2 | ||

| Not likely at all | 13.8 | 33.3 | ||

| When you have difficulties either falling asleep or getting back to sleep, you… | ||||

| Stay in bed and try to get some rest | 387.0 | .45 | ||

| Very likely | 34.5 | 47.2 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 48.3 | 27.8 | ||

| Not very likely | 10.3 | 5.6 | ||

| Not likely at all | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Do something in bed (read or watch TV) | 271.0 | .002 | ||

| Very likely | 13.8 | 41.7 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 41.4 | 44.4 | ||

| Not very likely | 34.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Not likely at all | 6.9 | 8.3 | ||

| Get up and read or watch TV | 441.5 | .76 | ||

| Very likely | 13.8 | 30.6 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 51.7 | 16.7 | ||

| Not very likely | 24.1 | 25.0 | ||

| Not likely at all | 6.9 | 19.4 | ||

| Get up and eat or drink something relaxing (such as warm milk) | 467.0 | .89 | ||

| Very likely | 3.4 | 13.9 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 58.6 | 41.7 | ||

| Not very likely | 17.2 | 19.4 | ||

| Not likely at all | 17.2 | 19.4 | ||

| Get up and drink alcohol | 354.0 | .03 | ||

| Very likely | 0.0 | 2.8 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Not very likely | 13.8 | 25.0 | ||

| Not likely at all | 82.8 | 58.3 | ||

| Get up and drink a caffeinated beverage | 395.5 | .16 | ||

| Very likely | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 0.0 | 2.8 | ||

| Not very likely | 13.8 | 22.2 | ||

| Not likely at all | 86.2 | 63.9 | ||

| Get up and start the day | 255.5 | .001 | ||

| Very likely | 3.4 | 13.9 | ||

| Somewhat likely | 20.7 | 52.8 | ||

| Not very likely | 44.8 | 16.7 | ||

| Not likely at all | 27.6 | 11.1 | ||

| How often do you do the following in bed? | ||||

| Read or watch TV | 199.5 | <.0005 | ||

| Never | 31.0 | 2.8 | ||

| Once a month or less | 13.8 | 8.3 | ||

| Once a week or less | 20.7 | 8.3 | ||

| A few times a week | 27.6 | 30.6 | ||

| Daily | 6.9 | 44.4 | ||

| Eat or drink | 263.5 | .003 | ||

| Never | 41.4 | 13.9 | ||

| Once a month or less | 31.0 | 13.9 | ||

| Once a week or less | 13.8 | 22.2 | ||

| A few times a week | 6.9 | 33.3 | ||

| Daily | 6.9 | 5.6 | ||

| Worry or spend time thinking | 276.0 | .002 | ||

| Never | 17.2 | 5.6 | ||

| Once a month or less | 37.9 | 11.1 | ||

| Once a week or less | 24.1 | 27.8 | ||

| A few times a week | 17.2 | 41.7 | ||

| Daily | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Argue or be angry | 331.5 | .03 | ||

| Never | 48.3 | 22.2 | ||

| Once a month or less | 31.0 | 30.6 | ||

| Once a week or less | 17.2 | 30.6 | ||

| A few times a week | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Daily | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Do work | 359.5 | .06 | ||

| Never | 65.5 | 41.7 | ||

| Once a month or less | 31.0 | 33.3 | ||

| Once a week or less | 3.4 | 5.6 | ||

| A few times a week | 0.0 | 2.8 | ||

| Daily | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

Sleep Health Beliefs

Rates of responses from both groups are reported in Table 4. There were no between-group differences on either of the items assessing family beliefs about sleep—both groups reported that they believed that sleep was important for children and that their parents made this important. In addition, when self-efficacy and motivation about sleep were assessed, both groups reported no statistically significant difference in likelihood of reporting that work or home responsibilities affected their sleep, and that they have control over their sleep and make keeping an adequate bedtime a priority. However, black respondents were less likely to report that they were motivated to make time for sleep. Also, there was a trend for black participants to be more likely to believe that sleepiness is due to laziness and bad habits.

Table 4.

Beliefs and Attitudes About Sleep in White and Black Participants

| Variable | Whites, % |

Blacks, % |

Group Differences (Mann- Whitney U) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Beliefs | ||||

| How important is obtaining good nightly sleep for children? | 416.5 | .13 | ||

| Very important | 44.8 | 58.3 | ||

| Important | 17.2 | 27.8 | ||

| Somewhat | 10.3 | 0.0 | ||

| Not important | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Don’t know | 27.6 | 13.9 | ||

| As you were growing up, did your parents emphasize a good night’s sleep? | 477.0 | .77 | ||

| No | 6.9 | 5.6 | ||

| Yes | 86.2 | 94.4 | ||

| Control/Self-efficacy | ||||

| My work responsibilities affect when and how much I sleep. | 399.5 | .19 | ||

| Strongly agree | 10.3 | 16.7 | ||

| Agree | 27.6 | 38.9 | ||

| Unsure | 6.9 | 0.0 | ||

| Disagree | 37.9 | 36.1 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 13.8 | 5.6 | ||

| My home responsibilities affect when and how much I sleep. | 418.5 | .16 | ||

| Strongly agree | 13.8 | 19.4 | ||

| Agree | 58.6 | 66.7 | ||

| Unsure | 10.3 | 0.0 | ||

| Disagree | 10.3 | 8.3 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 6.9 | 2.8 | ||

| I have control over when and how much I sleep. | 465.0 | .58 | ||

| Strongly agree | 13.8 | 13.9 | ||

| Agree | 34.5 | 22.2 | ||

| Unsure | 24.1 | 38.9 | ||

| Disagree | 20.7 | 25.0 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 0.0 | ||

| I am motivated to make sure that I have enough time to sleep. | 307.0 | .006 | ||

| Strongly agree | 17.2 | 5.6 | ||

| Agree | 58.6 | 38.9 | ||

| Unsure | 20.7 | 22.2 | ||

| Disagree | 3.4 | 27.8 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Going to bed at a suitable time is an important part of my routine. | 506.5 | .11 | ||

| Strongly agree | 44.8 | 25.0 | ||

| Agree | 27.6 | 38.9 | ||

| Unsure | 24.1 | 13.9 | ||

| Disagree | 3.4 | 19.4 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| People who fall asleep at work or school are lazy or have bad habits. | 363.0 | .06 | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.9 | 2.8 | ||

| Agree | 10.3 | 36.1 | ||

| Unsure | 10.3 | 16.7 | ||

| Disagree | 58.6 | 33.3 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 10.3 | 8.3 | ||

| Coping With Sleep Difficulties and Sleepiness | ||||

| Boredom makes you sleep even if you slept enough the night before. | 349.0 | .02 | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.9 | 11.1 | ||

| Agree | 37.9 | 58.3 | ||

| Unsure | 3.4 | 11.1 | ||

| Disagree | 48.3 | 13.9 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 2.8 | ||

| Lying in bed with your eyes shut is as good as sleeping | 292.5 | .007 | ||

| Strongly agree | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Agree | 13.8 | 25.0 | ||

| Unsure | 13.8 | 22.2 | ||

| Disagree | 69.0 | 30.6 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 2.8 | ||

| I can tell when I am sleepy. | 406.0 | .34 | ||

| Strongly agree | 13.8 | 25.0 | ||

| Agree | 72.4 | 69.4 | ||

| Unsure | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Disagree | 3.4 | 2.8 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Opening the car window is a good way to wake me up if I am drowsy while driving. | 323.0 | .01 | ||

| Strongly agree | 17.2 | 8.3 | ||

| Agree | 58.6 | 25.0 | ||

| Unsure | 3.4 | 30.6 | ||

| Disagree | 17.2 | 25.0 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 5.6 | ||

| Turning up the volume of the radio or music is a good way to wake me up if I am drowsy while driving. | 350.5 | .04 | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.9 | 5.6 | ||

| Agree | 62.1 | 33.3 | ||

| Unsure | 6.9 | 22.2 | ||

| Disagree | 17.2 | 27.8 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Sleep and Health | ||||

| Getting enough sleep is important for me to be able to enjoy the daytime. | 305.0 | .008 | ||

| Strongly agree | 62.1 | 25.0 | ||

| Agree | 24.1 | 52.8 | ||

| Unsure | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Disagree | 6.9 | 8.3 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| My sleep is important to my health. | 381.5 | .004 | ||

| Strongly agree | 62.1 | 36.1 | ||

| Agree | 31.0 | 27.8 | ||

| Unsure | 6.9 | 25.0 | ||

| Disagree | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Not getting enough sleep can lead to serious consequences. | 346.0 | .07 | ||

| Strongly agree | 48.3 | 36.1 | ||

| Agree | 41.4 | 22.2 | ||

| Unsure | 6.9 | 25.0 | ||

| Disagree | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Poor sleep affects the quality of my life. | 361.5 | .09 | ||

| Strongly agree | 48.3 | 19.4 | ||

| Agree | 27.6 | 50.0 | ||

| Unsure | 10.3 | 16.7 | ||

| Disagree | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 6.9 | 0.0 | ||

| Dozing while driving a vehicle is serious. | 232.0 | <.0005 | ||

| Strongly agree | 93.1 | 36.1 | ||

| Agree | 3.4 | 55.6 | ||

| Unsure | 3.4 | 2.8 | ||

| Disagree | 0.0 | 2.8 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| I have seen information about sleep problems on TV or the Internet. | 401.0 | .23 | ||

| Strongly agree | 44.8 | 13.9 | ||

| Agree | 31.0 | 63.9 | ||

| Unsure | 6.9 | 8.3 | ||

| Disagree | 13.8 | 5.6 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 0.0 | ||

| I have seen or talked about sleep problems with my doctor. | 506.0 | .98 | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.9 | 11.1 | ||

| Agree | 17.2 | 2.8 | ||

| Unsure | 10.3 | 2.8 | ||

| Disagree | 34.5 | 63.9 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 31.0 | 16.7 | ||

| My doctor has discussed the importance of regular and adequate sleep. | 367.0 | .28 | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.9 | 5.6 | ||

| Agree | 6.9 | 2.8 | ||

| Unsure | 20.7 | 0.0 | ||

| Disagree | 31.0 | 50.0 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 31.0 | 27.8 | ||

| I use my bedroom for sleep and sex only. | 414.5 | .60 | ||

| Strongly agree | 13.8 | 5.6 | ||

| Agree | 31.0 | 44.4 | ||

| Unsure | 0.0 | 11.1 | ||

| Disagree | 48.3 | 19.4 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3.4 | 8.3 | ||

| Health problems such as being overweight (obesity), high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression are related to the amount of sleep I get. | 458.5 | .63 | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.9 | 8.3 | ||

| Agree | 20.7 | 5.6 | ||

| Unsure | 10.3 | 22.2 | ||

| Disagree | 51.7 | 52.8 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 6.9 | 8.3 | ||

There were small between-group differences for beliefs regarding coping with sleepiness. Black participants were more likely to believe that lying in bed with eyes shut is as good as sleeping. Trends for black participants included being more likely to believe that boredom causes sleepiness even if one slept well, and less likely to believe that rolling down the window or playing music loudly are good strategies for alleviating sleepiness while driving. There were no significant differences in the percentage of black or white participants who believed that they could accurately tell if they are sleepy.

Regarding beliefs about how sleep is related to health outcomes, white participants were more likely to believe that sleep is related to one’s health and ability to enjoy the daytime. A trend was found, suggesting that white participants may be more likely to believe that lack of sleep can lead to negative consequences. However, groups were highly significantly different in their beliefs regarding the seriousness of dozing while driving a vehicle—black participants were less likely than white participants to strongly agree with this statement. Also, there were no significant differences between groups for endorsement of the belief that sleep is related to health problems such as obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression. Most of the white (68.9%) and black (83.3%) respondents reported that they were either unsure of this or that they disagreed with the statement.

No differences for exposure to sleep-related information were found, and both groups reported that they generally do not discuss sleep problems with their doctor, and their doctor generally does not discuss the importance of regular and adequate sleep with them. Additionally, despite the sleep hygiene findings above, there was no between-group difference regarding reports of using of the bedroom for sleep and sex only.

DISCUSSION

The current paper explored sleep-related complaints, practices, and beliefs in white and black participants. Overall, black participants were more likely to report snoring and were characterized by a greater discrepancy between habitual sleep duration and perceived need. In addition, black participants reported more sleep hygiene infractions and reported beliefs that suggested less of an understanding of the importance of good sleep for health, although the majority of members of both groups stated that poor sleep did not have negative effects on other health conditions or were unsure of this relationship. Both groups rarely discussed sleep problems with their health care provider, though research suggests that black individuals are more likely to discuss health issues with elders, clergy, and healers in the community.29

Sleep in Older Adult Women

The focus of this study was on women (primarily older women took part) who represent a unique group in a number of ways. Given the age range, most or all of these women were postmenopausal (though this was not assessed). Previous research on postmenopausal women has shown that most in this group report problems with frequent nighttime awakenings and daytime sleepiness.30 In addition, few differences in sleep duration and insomnia complaints existed across racial (and socioeconomic) categories, except that black women were more likely to report longer sleep.30 This is in contrast to other findings that suggest that black postmenopausal women are more likely to be short sleepers on objective measures.31 Additionally, this discrepancy was partially explained by increased oxygen desaturations. Although this group may be likely to experience sleep problems and some racial differences may exist, previous studies have not explored differences in sleep practices and beliefs.

Sleep-Related Complaints

Although overall measures of sleep quality and daytime sleepiness did not show significant differences between the 2 groups, more indirect measures detected a difference. Thus, when subjects were prompted for complaints of problems, they were generally not reported; however, differences were found in an item that was not necessarily a complaint but may indicate symptoms of sleep apnea (ie, snoring) and a computed variable that was not asked directly (ie, discrepancy between sleep need and sleep duration). So while complaints were not reported outright, some differences were found.

The finding that outright sleep quality complaints did not differentiate the groups was not surprising, as recent large-scale epidemiological studies have found that general sleep complaints are not differentially reported in black and white respondents,16 though other studies have found differences in sleep complaints.9 A lack of difference in complaints may belie problems, as black individuals are at greater risk of disturbed sleep (eg, symptoms of sleep apnea) when measured in the laboratory,32 suggesting a discrepancy between reported symptoms and those observed. This discrepancy may be because general measures do not capture differences in sleep experience, or other factors such as demand characteristics of surveys and social desirability come into play. Black individuals may not see inadequate sleep as a complaint worth mentioning or as being a low priority, especially if the reasons that they sleep less are related to activities that they value highly, such as spending time with family or working to support their family. Thus, while they may perceive insufficient sleep, they may not see this as something about which to complain.

This may explain why we did find that, when reported sleep need and duration were evaluated, black respondents reported a greater likelihood of not sleeping as long as they felt they needed. It is worth noting that this finding was not based on any complaints by black respondents—they did not report insufficient sleep directly. Thus, in the future, research in the black population (or other nonwhite populations) might benefit from this approach: probing for disparities without asking for complaints directly.

The symptom of snoring was endorsed to a greater extent by black relative to white participants. While other symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea were not assessed, this finding of increased snoring is consistent with other research that has shown that black individuals are at greater risk for developing obstructive sleep apnea32 and may reflect differences in sleep apnea risk factors such as obesity or anatomical differences in the airway (which were not assessed in this pilot study). However, it is also possible that there is a differential ethnic bias with respect to the acceptability of reporting snoring.

Sleep Hygiene Practices

Overall, groups were roughly similar in strategies for coping with sleepiness, with the exception that black participants were more likely to nap during the day. Groups differed in strategies for coping with difficulties falling asleep, in that black participants were more likely to drink alcohol (which is more likely to exacerbate problems rather than ameliorate them33,34) and do something in bed (which is often a maladaptive coping strategy that places them at increased risk of developing psychophysiological insomnia4). Additionally, black participants were more likely to report getting up to start their day, which may reflect an inability to return to sleep35 or, conversely, may reflect the adaptive coping strategy of stimulus control.36 That this reflects stimulus control is unlikely, as black respondents were more likely to engage in a number of nonsleep activities in bed (thus practicing poorer stimulus control in those situations). That black individuals were more likely to engage in activities besides sleep in bed and other potentially maladaptive coping strategies reflects either a disparity in knowledge about healthy sleep practices or the presence of other factors that predispose this group to insomnia. Future studies should examine whether these specific self-reported practices are consistent with other reports of habitual sleep hygiene using established measures.37

Beliefs About Sleep and Health

Despite findings from other health domains suggesting significant differences in cultural practices regarding a number of health behaviors,38–41 these preliminary data suggest that family attitudes about sleep are roughly the same in white and black groups. However, future studies with more sensitive items may detect differences.

Black respondents were less likely to report motivation to make time for sleep. As mentioned above, this may be because sleep is not seen as a priority. Further exploring and addressing this issue will be critical in the outcome of interventions targeted to this group. Part of the reason for this attitude may be reflected in the trend for black respondents to believe that sleepiness is due to laziness and bad habits. When paired with the finding that black participants were less likely to believe that falling asleep while driving a vehicle was serious, a general lack of understanding about sleep, sleepiness, and the relationship between sleep and health is evident. Furthermore, this is supported by the endorsement of several beliefs that suggest that black respondents do not appreciate the importance of sleep for health. Black participants were less likely to believe that sleep is related to one’s health and ability to enjoy the daytime, and more likely to believe that lying in bed with eyes shut is as good as sleeping. Perhaps most telling were responses regarding the belief that sleep is related to health outcomes, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression. It is important to emphasize that both black and white groups were not likely to endorse this, reflecting a general lack of understanding across race about the importance of sleep. This may be due to a general lack of information. No differences in exposure to sleep-related information or sleep-related conversations with doctors were reported.

Implications of Socioeconomic Indicators

A majority of the subjects, regardless of race or community center, reported incomes below $40 000. This would suggest that in this group, observed race differences are not simply related to differences in socioeconomic status but probably related to culture and social environment. Therefore, the findings support the need to employ a multilevel socioecological approach in subsequent studies.

Further, the fact that there are not profound differences should not be surprising, because most participants were of a common age group and socioeconomic group, and live in the same neighborhood. While they may be of different races, they share many commonalities that would influence “culture.”

STUDY LIMITATIONS

There are several important limitations to this study. First, while there was no difference between groups for income, there was a highly significant difference between groups regarding educational attainment. This may have confounded results, limiting interpretation. It may be that observed group differences reflected differences in educational attainment, rather than cultural or other factors. Also, the difference in education level may also reflect other important differences between groups that were not assessed. As large a difference as this was, it was not reflected in areas one might expect, including knowledge about the relationship of sleep to health and likelihood of discussing sleep with a doctor. Second, that the data were nonparametric limited our options for statistical tests. While the Mann-Whitney tests were the most appropriate for the data, they are unable to adjust or control for covariates, including age and socioeconomic factors. Although these variables (with the exception of education) did not distinguish groups, future studies should better address this problem. Also, black and white categories may potentially reflect a broad diversity of cultural and ethnic identities, which were not measured in more detail. This is a limitation of virtually all studies that have examined race in relation to health. Additionally, we did not incorporate previously used measures of sleep-related beliefs (eg42–44). While this is true, those questionnaires do not assess most of the issues evaluated in the current study. Finally, no data were obtained regarding signs and symptoms of sleep disorders or other comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions, or medications that may have an effect on sleep. Thus, we were unable to determine how these factors affect the relationship of race/ethnicity to sleep complaints, practices, and beliefs.

CONCLUSION

This study represents one of the first attempts to assess habitual sleep practices and beliefs in a lowincome community, contrasting black and white groups. Although the study had many limitations, the results suggest that black individuals are less likely to engage in adaptive coping strategies to address sleep problems and more likely to endorse beliefs and attitudes about sleep that reflect a lack of understanding about the importance of sleep. Additionally, that there were no differences on several measures suggests that both groups tend to see sleep as minimally important, and neither group addresses sleep issues with their doctor, despite equal access to sleep information in the media.

Future research needs to explore sleep-related practices, beliefs, and attitudes in a number of racial/ethnic groups. The next step would be for larger studies to explore this issue in more detail, leading to even larger, multisite studies that explore how sleep is perceived, and how sleep-related behaviors are taught and carried out in the general population. This will lay the necessary groundwork for the sorts of large-scale community-based and population-based interventions that have proven successful in other domains

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This research was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (T32HL007713) and the University of Pennsylvania Resource Center of Minority Aging Research (P30-AG-031043–01 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging).

REFERENCES

- 1.Borbely AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1(3):195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuller PM, Saper CB, Lu J. The pontine REM switch: past and present. J Physiol. 2007;584(Pt 3):735–741. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.140160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siebern AT, Manber R. Insomnia and its effective non-pharmacologic treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94(3):581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(3):205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espie CA, Kyle SD. Primary insomnia: An overview of practical management using cognitive behavioral techniques. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4:559–569. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluestein D, Rutledge CM, Healey AC. Psychosocial correlates of insomnia severity in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(2):204–211. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliwise DL. Cross-Cultural Influences on Sleep—Broadening the Environmental Landscape. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(12):1365–1366. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherniack EP, Ceron-Fuentes J, Florez H, et al. Influence of race and ethnicity on alternative medicine as a self-treatment preference for common medical conditions in a population of multi-ethnic urban elderly. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(2):116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jean-Louis G, Magai C, Casimir GJ, et al. Insomnia symptoms in a multiethnic sample of American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(1):15–25. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jean-Louis G, Magai C, Consedine NS, et al. Insomnia symptoms and repressive coping in a sample of older Black and White women. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Perlis ML, et al. Obesity, diabetes, and exercise associated with sleep-related complaints in the American population. J Public Health. doi: 10.1007/s10389-011-0398-2. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grandner MA, Youngstedt SD. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk. Atherosclerosis. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.046. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandner MA, Lang RA, Jackson NJ, et al. Biopsychosocial predictors of insufficient rest or sleep in the American population. Sleep. 2011;34(abstract suppl):A260. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman NG, Zhao Z, Jackson NJ, et al. Sleep duration versus sleep insufficiency as predictors of cardiometabolic health outcomes. Sleep. 2011;34(abstract suppl):A51. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Hale L, et al. Mortality associated with sleep duration: The evidence, the possible mechanisms, and the future. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, et al. Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep disturbance. Sleep Med. 2010;11:470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, et al. Problems associated with short sleep: Bridging the gap between laboratory and epidemiological studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickering T. Cardiovascular pathways: socioeconomic status and stress effects on hypertension and cardiovascular function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:262–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chien KL, Chen PC, Hsu HC, et al. Habitual sleep duration and insomnia and the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause death: Report from a community-based cohort. Sleep. 2010;33(2):177–184. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muraki I, Tanigawa T, Yamagishi K, et al. Nocturnal Intermittent Hypoxia and Metabolic Syndrome; the Effect of being Overweight: the CIRCS Study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(4):369–377. doi: 10.5551/jat.3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse DJ, Grunstein R, Horne J, et al. Can an improvement in sleep positively impact on health? Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(6):405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buxton OM, Marcelli E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(5):1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azjen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory, Res Pract. 1982;19(3):276–288. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egede LE, Bonadonna RJ. Diabetes self-management in African Americans: an exploration of the role of fatalism. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(1):105–115. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1101–1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortune T, Wright E, Juzang I, et al. Recruitment, enrollment and retention of young black men for HIV prevention research: Experiences from The 411 for Safe Text project. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;31(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kripke DF, Brunner R, Freeman R, et al. Sleep complaints of postmeno-pausal women. Clin J Womens Health. 2001;1(5):244–252. doi: 10.1053/cjwh.2001.30491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kripke DF, Jean-Louis G, Elliott JA, et al. Ethnicity, sleep, mood, and illumination in postmenopausal women. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jean-Louis G, von Gizycki H, Zizi F, et al. Evaluation of sleep apnea in a sample of black patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):421–425. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmenhorst D, Elmenhorst EM, Luks N, et al. Performance impairment during four days partial sleep deprivation compared with the acute effects of alcohol and hypoxia. Sleep Med. 2009;10(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singleton RA, Jr., Wolfson AR. Alcohol consumption, sleep, and academic performance among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(3):355–363. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durrence HH, Lichstein KL. The sleep of African Americans: a comparative review. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(1):29–44. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0401_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chesson AL, Jr., Anderson WM, Littner M, et al. Practice parameters for the nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 1999;22(8):1128–1133. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.8.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mastin DF, Bryson J, Corwyn R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. J Behav Med. 2006;29(3):223–227. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyington JE, Carter-Edwards L, Piehl M, et al. Cultural attitudes toward weight, diet, and physical activity among overweight African American girls. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(2):A36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, et al. Culture and systems of thought: holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(2):291–310. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarlov AR. Public policy frameworks for improving population health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:281–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Psychological Association. Guidelines for providers of psychological services to ethnic, linguistic, and culturally diverse populations. Am Psychol. 1993;48(1):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morin CM, Vallieres A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): validation of a brief version (DBAS-16) Sleep. 2007;30(11):1547–1554. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Owens JA, Stahl J, Patton A, et al. Sleep practices, attitudes, and beliefs in inner city middle school children: a mixed-methods study. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(2):114–134. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0402_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adan A, Fabbri M, Natale V, et al. Sleep Beliefs Scale (SBS) and circa-dian typology. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(2):125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]