Summary

Although echocardiography-derived tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV) is associated with increased mortality in sickle cell disease (SCD), its rate of increase and predictive markers of its progression are unknown. We evaluated 55 subjects (median age: 38 years, range: 20 – 65 years) with at least 2 measurable TRVs, followed for a median of 4.5 years (range: 1.0 – 10.5 years) in a single-centre, prospective study. Thirty-one subjects (56%) showed an increase in TRV, while 24 subjects (44%) showed no change or a decrease in TRV. A linear mixed effects model indicated an overall rate of increase in the TRV of 0.02 m/s per year (p = 0.023). The model showed that treatment with hydroxycarbamide was associated with an initial TRV that was 0.20 m/s lower than no such treatment (p = 0.033), while treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers was associated with an increase in the TRV (p = 0.006). In summary, although some patients have clinically meaningful increases, the overall rate of TRV increase is slow. Treatment with hydroxycarbamide may decrease the progression of TRV. Additional studies are required to determine the optimal frequency of screening echocardiography and the effect of therapeutic interventions on the progression of TRV in SCD.

Keywords: Sickle Cell Disease, Pulmonary Hypertension, Tricuspid Regurgitant Jet Velocity, Progression, Hydroxycarbamide

Introduction

The prevalence of echocardiography-defined pulmonary hypertension (subsequently referred to as pulmonary hypertension [PHT] risk), based on a tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV) ≥ 2.5 m/s, in adult patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) is approximately 30% (Ataga, et al 2004, Gladwin, et al 2004). Using the modified Bernoulli equation, the TRV provides a calculated estimate of right ventricular and pulmonary artery systolic pressures (PASP = 4TRV2 + estimated right atrial pressure) (Yock and Popp 1984). Although recent studies suggest that echocardiography-assessed TRV may over-estimate the prevalence of PHT (Fonseca, et al 2011, Parent, et al 2011), elevated TRV is recognized as an independent predictor of mortality in SCD (Ataga, et al 2006, De Castro, et al 2008, Gladwin, et al 2004). Because of this association with increased mortality, many authors have recommended routine screening of SCD patients with Doppler echocardiography (Ataga, et al 2006, De Castro, et al 2008, Gladwin, et al 2004). However, as the rate of increase of the TRV is unknown, the optimal frequency of screening echocardiography remains unknown. In this study, we have evaluated the rate of increase of TRV and assessed the predictive markers of such increase in adult patients with SCD.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Study Design

This study was conducted as a single-centre, prospective evaluation of the rate of increase of echocardiography-derived TRV in adult patients with SCD. The study subjects represent a cohort of patients followed at the Sickle Cell Clinic at the University of North Carolina (UNC), Chapel Hill. The data were collected as part of a study to investigate the pathophysiology and natural history of PHT in SCD (Ataga, et al 2006). Consecutive SCD patients seen in the clinic for routine follow up, who agreed to participate, were evaluated.

Subjects who had an echocardiogram on more than one occasion during the course of the study and had more than one measurable TRV were evaluated. The effect of select interventions on TRV was assessed by a review of subject charts. Interventions were for a minimum of 12 months duration and included: treatment with hydroxycarbamide (also known as hydroxyurea), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB); chronic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion; chronic oxygen therapy; and/or PHT-specific therapy. Each subject was studied in the non-crisis, “steady state,” and had not had acute chest syndrome in the 4 weeks preceding enrollment, and had no evidence of congestive heart failure. Written informed consent was obtained and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UNC, Chapel Hill.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography was performed in all SCD patients using a Hewlett-Packard 2500 Ultrasound System, with a 2.5/2.0 MHz ultrasound probe (Model 21215A) for recording continuous wave signals. Echocardiograms were interpreted by a cardiologist blinded to all the patients’ data. Multiple views (apical four-chamber, short axis and tricuspid inflow) were obtained to record optimal tricuspid flow signals. The TRV was measured using continuous wave Doppler echocardiography on at least three waveforms with well-defined velocity envelopes and an average value (expressed to the nearest 0.1 m/s) used for data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data were dichotomized to evaluate for associations between increased TRV (an increase of at least 0.1 m/s) compared with no increase in TRV (decreased TRV and no change in TRV). Associations between increased TRV and clinical and laboratory covariates were obtained using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and Fishers Exact Test for dichotomous variables. Linear mixed effects models were used to analyse the rate of increase of TRV and included both a random intercept and time effect for each subject. Linear mixed models were used because the TRV assessments were not obtained at fixed intervals in all the study subjects. Reported p-values are considered ‘nominal’ and are for individual tests, unadjusted for multiple comparisons because of the exploratory nature of this study. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (www.r-project.org).

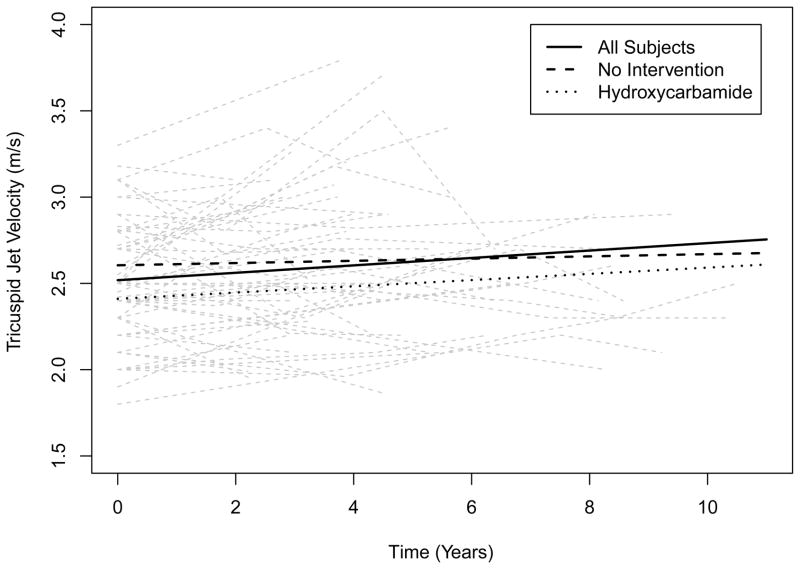

Results

One hundred and sixty-four subjects were evaluated in this study. Of the 76 subjects who had more than one echocardiographic assessment, 9 had no measurable TRV and 12 had only one measurable value. Fifty five subjects (30 female, 25 male; SS – 46, SC – 4, Sβ0 – 3, Sβ+ - 2), with a median age of 38.0 years (range: 20 – 65 years), had at least 2 measurable TRVs and were followed for a median of 4.5 years (range 1.0 – 10.5 years) (Table I). Two measurable TRVs were obtained in 30 subjects, 3 measurable values were obtained in 16 subjects, 4 measurable values were obtained in 7 subjects, and 5 measurable values were obtained in 2 subjects. Thirty-one subjects (56%) showed an increase in TRV (median baseline: 2.5 m/s, range: 1.8 – 3.3), while 24 subjects (44%) showed no change or a decrease in TRV (median baseline: 2.5 m/s, range: 2.0 – 3.2). Of the 22 subjects who had a TRV value > 2.5 m/s at baseline, 12 (54.5%) had subsequent increases in the TRV and 10 (45.5%) did not. Of the 33 subjects with a TRV ≤ 2.5 at baseline, 19 (57.6%) had subsequent increases in the TRV and 14 (42.4%) did not. The proportion of subjects with an increase in TRV in each of these groups were not statistically different (p = 1.0, Fishers Exact Test). A linear mixed effects model estimated an initial TRV of 2.5 m/s (observed baseline TRV ranged from 1.8 to 3.3 m/s) and a rate of increase of 0.02 m/s/year (p = 0.023) for all the study subjects (Figure 1). For those subjects with an increase in TRV, the model predicted a rate of increase of 0.07 m/s/year. While subjects with an initial TRV ≥ 2.5 m/s were predicted to have an increase over time that was slightly greater than those with an initial TRV < 2.5 m/s, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.68). Seven subjects were noted to have an initial TRV of 3.0 m/s or higher, with 15 subjects found to have at least one TRV value of 3.0 m/s during the course of the study (Figure 1). In addition, there were 18 subjects with initial TRVs of between 2.5 and 2.8 m/s, 8 (44.4 %) of whom (median: 2.65 m/s, range: 2.5 – 2.8) experienced subsequent increases in their TRV values to ≥ 3.0 m/s during the course of the study.

Table I.

Demographic and Laboratory Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Variable | Number of Subjects | Median (min, max) or Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 55 | 38 (20, 65) | ||

|

| ||||

| Gender | 55 | |||

| (Male) | 25 (45%) | |||

| (Female) | 30 (55%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Genotype | 55 | |||

| (SS) | 46 (83.6%) | |||

| (SC) | 4 (7.3) | |||

| (Sβ0) | 3 (5.5%) | |||

| (Sβ+) | 2 (3.6) | |||

|

| ||||

| Weight (kg) | 55 | 69.6 (47.2, 176.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Time between echocardiography assessments (years) | 55 | 2.9 (1.0, 8.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| White blood cell count (x 109/l) | 55 | 9.1 (4.3, 15.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 55 | 87 (38, 128) | ||

|

| ||||

| Platelet count (x 109/l) | 54 | 372 (160, 1054) | ||

|

| ||||

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 52 | 7.0 (1.9, 24.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Fetal Haemoglobin (%) | 55 | 6.1 (0.0, 32.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Use of hydroxycarbamide | 55 | |||

| (No) | 28 (51%) | |||

| (Yes) | 27 (49%) | |||

Figure 1.

Change in tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV) over time in all subjects (solid line), with no intervention (broken line) and on hydroxycarbamide (dotted line). At baseline, all patients had an estimated TRV of 2.5 m/s, with an estimated rate of increase of 0.02 m/s per year. At baseline, patients without any interventions had an estimated TRV of 2.6 m/s, with an estimated rate of increase of 0.01 m/s per year. At baseline, patients on hydroxycarbamide for at least 12 months prior to enrollment had an estimated TRV of 2.4 m/s, with an estimated rate of increase of 0.01 m/s per year.

For study subjects not receiving any therapeutic interventions for SCD-related complications at study enrollment, the model estimated an initial TRV of 2.6 m/s, and a rate of decrease in TRV of 0. 01 m/s/year (p = 0.79). The study subjects on hydroxycarbamide at enrollment (N = 26) were found to have an initial TRV that was 0.2 m/s lower than those not on hydroxycarbamide (p = 0.033), with a predicted rate of increase of 0.018 m/s/year for subjects on hydroxycarbamide compared to 0.025 m/s/year for subjects not on hydroxycarbamide (p = 0.72). The study subjects on hydroxycarbamide for at least 12 months during the study (N = 33) were predicted to have an increase in the TRV of 0.01 m/s/year, not significantly different from the 0.04 m/s/year increase predicted for subjects not on hydroxycarbamide (p = 0.19). When hydroxycarbamide status was treated as a time-varying covariate, no significant differences were observed in the TRV or rate of increase of TRV when subjects on hydroxycarbamide were compared to those not on such therapy (data not shown). The study subjects on ACE inhibitors/ARBs at enrollment (N = 6) were found to have an initial TRV that was 0.06 m/s higher than subjects not on such therapies (p = 0.69). In addition, the study subjects on ACE inhibitors/ARBs for at least 12 months during the study (N = 13) were predicted to have an increase in TRV that was 0.06 m/s/year greater than those not on ACE inhibitors/ARBs (p = 0.006). When the status of ACE inhibitors/ARBs was treated as a time-varying covariate, subjects on ACE inhibitors/ARBs were found to have a TRV that was 0.03 m/s lower than subjects not on such therapies (p = 0.75), but were predicted to have an increase in TRV of 0.07 m/s/year more than subjects not on ACE inhibitors/ARBs (p = 0.03). The individual effects of chronic RBC transfusion (N = 2), PHT-specific treatments (N = 2) and chronic oxygen therapy (N = 5) were not assessed.

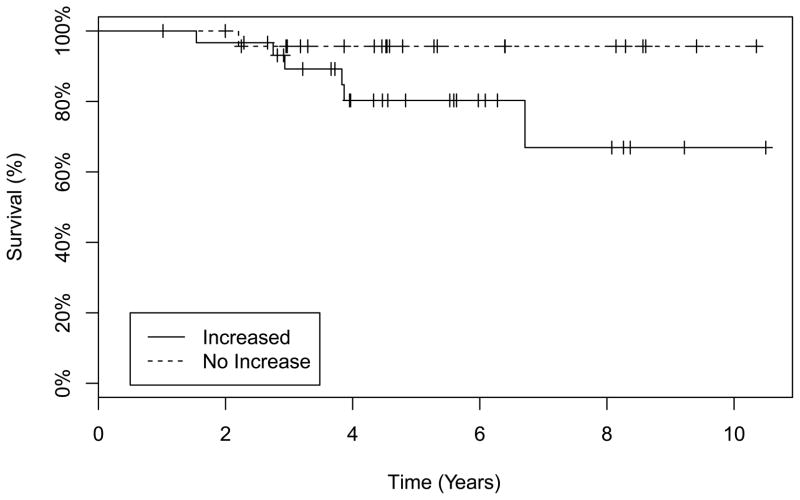

There was a significant difference in the level of direct bilirubin (p = 0.05) when subjects with an increase in TRV were compared to those with no change or a decrease in the TRV. No differences were observed in other evaluated laboratory variables (Table II). Six of 31 subjects with an increase in TRV died compared to 1 of 24 subjects with no increase in the TRV, but the difference did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.12) (Table III). Furthermore, when the deceased subjects in both groups were compared using a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed (p = 0.09, log rank test) (Figure 2). Of the 6 deceased subjects in the increased TRV group, 2 were on hydroxycarbamide and 4 were not. The 1 deceased subject in the no increase group was on hydroxycarbamide. Discussion:

Table II.

Association of Tricuspid Regurgitant Jet Velocity (TRV) with Laboratory Variables

| Variable | Increased in TRV | Decreased or No Change in TRV | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (IQR; 25, 75) | N | Median (IQR; 25, 75) | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 31 | 89 (79, 100) | 24 | 86 (79, 102) | 0.95 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 30 | 6.2 (4.1, 9.15) | 22 | 8.6 (5.5, 11.8) | 0.08 |

| Fetal haemoglobin (%) | 31 | 5.9 (2.4, 10.0) | 24 | 8.6 (3.7, 15.3) | 0.25 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (u/l) | 12 | 966.5 (66.8, 1243.0) | 9 | 1136 (808, 1692) | 0.22 |

| Direct bilirubin (mmol/l) | 12 | 1.7 (1.7, 5.1) | 9 | 1.7 (1.7, 1.7) | 0.05 |

| Indirect bilirubin (μmol/l) | 12 | 34.2 (20.5, 68.4) | 9 | 46.2 (32.5, 75.2) | 0.34 |

| Platelet count (x 109/l) | 30 | 370.0 (302.2, 449.0) | 24 | 396 (292.5, 525.0) | 0.80 |

| White blood cell count (x 109/l) | 31 | 9.0 (6.9, 11.2) | 24 | 11.0 (8.1, 13.1) | 0.11 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (x 109/l) | 12 | 4.4 (3.2, 4.8) | 9 | 5.8 (4.3, 6.6) | 0.19 |

| Absolute monocyte count (x 109/l) | 12 | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | 9 | 0.5 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.72 |

| Soluble VCAM-1 (ng/ml) | 11 | 660.0 (518.5, 1242.0) | 9 | 624.0 (550.0, 886.0) | 0.66 |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 12 | 70.7 (61.9, 88.4) | 9 | 61.9 (61.9, 123.8) | 0.77 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/l) | 11 | 2.9 (2.5, 5.2) | 9 | 3.6 (3.2, 5.0) | 0.47 |

| NT Pro-BNP (pg/ml) | 12 | 229.5 (61.2, 430.5) | 9 | 65.0 (54.0, 186.0) | 0.37 |

IQR - interquartile range

NT-Pro BNP – N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

VCAM-1 – Vascular cell adhesion molecule - 1

Table III.

Association of Tricuspid Regurgitant Jet Velocity (TRV) with Clinical Variables

| Variable | Increased in TRV | Decreased or No Change in TRV | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | |||

| Gender | Female | 18 | 12 | 0.59 |

| Male | 13 | 12 | ||

| Smoking Status | Yes | 10 | 10 | 0.58 |

| No | 21 | 14 | ||

| History of Leg Ulcer | Yes | 9 | 8 | 0.78 |

| No | 22 | 16 | ||

| History of Acute Chest Syndrome | Yes | 25 | 17 | 0.53 |

| No | 6 | 7 | ||

| Genotype | SS/Sβ0/SD | 24 | 23 | 0.12 |

| SC/Sβ+ | 7 | 1 | ||

| Number of Painful Episodes in Past Year | <3 | 8 | 5 | 0.67 |

| ≥3 | 4 | 4 | ||

| History of Stroke | Yes | 3 | 2 | 1.0 |

| No | 28 | 22 | ||

| Mortality | Yes | 6 | 1 | 0.12 |

| No | 25 | 23 | ||

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Plot comparing the subjects with an increase in tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV) and those with a decreased or no change in TRV. There was no statistically significant difference when both groups were compared (p = 0.09, log rank test).

The utility of screening echocardiography in SCD-associated PHT remains controversial (Bunn, et al 2010, Hassell 2010). This is due to the modest correlation that has been observed between PASP estimated on echocardiography and values measured on right heart catheterization (Fonseca, et al 2011, Parent, et al 2011). A recent multicentre study found no evidence of PHT following right heart catheterization in 72 of 96 patients with elevated TRV on echocardiography (Parent, et al 2011), suggesting that a cut-off value of 2.5 m/s on Doppler echocardiography may be too low for defining PHT in patients with SCD. In addition, while patients are frequently treated with agents approved for pulmonary arterial hypertension, there are, to date, no proven therapies for SCD-associated PHT (Barst, et al 2010, Machado, et al 2011). However, as TRV is a recognized marker of increased mortality in SCD (Ataga, et al 2006, De Castro, et al 2008, Gladwin, et al 2004), knowledge of its rate of change could help determine the frequency of screening echocardiograms in this population. In our patient cohort, we found that TRV increases with time, albeit at a slow rate. With this predicted slow rate of increase in the TRV, there does not appear to be a reason to obtain yearly screening echocardiograms on all patients as an annual increase of 0.02 m/s/year is not clinically meaningful. However, a subset of patients with baseline TRV values of between 2.5 m/s and 2.8 m/s appear to have more clinically meaningful increases in their TRVs and may benefit from more frequent echocardiographic screenings, followed by right heart catheterization if the TRV is at least 3.0 m/s or if they develop symptoms and/or signs suggestive of PHT. Recent reports suggest that compared to a value of 2.5 m/s, a TRV greater than 2.9 m/s has a greater predictive value for right heart catheterization-confirmed PHT (Mehari, et al 2012, Parent, et al 2011). Indeed, 4 of the 7 subjects with initial TRV of ≥ 3.0 m/s in our cohort who agreed to undergo a right heart catheterization had PHT (pulmonary arterial hypertension in 2 subjects and pulmonary venous hypertension in 2 subjects).

Although most evaluated variables were not associated with an increase in TRV, the number of subjects in our study was relatively small. The significance of the association of direct bilirubin with an increase in TRV is uncertain. While not statistically significant, there appeared to be a higher risk of death in subjects who experienced an increase in their TRVs. This finding further highlights the increased risk of mortality with increased TRV in SCD. The significantly lower baseline TRV and the lower rate of increase in TRV in patients on hydroxycarbamide suggest that this therapeutic intervention may be beneficial in SCD-associated PHT. There are no controlled studies in this setting (Ataga, et al 2006, Olnes, et al 2009, Pashankar, et al 2009), but hydroxycarbamide may provide benefit to patients with SCD by: decreasing haemolysis with increases in levels of fetal haemoglobin (Carache, et al 1995); modulating endothelial function by decreasing levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (Kato, et al 2005, Saleh, et al 1999); decreasing the release of the vasoconstrictor peptide, endothelin-1 (Brun, et al 2003); and increasing the generation of nitric oxide (Gladwin, et al 2002, Glover, et al 1999). While patients receive hydroxycarbamide as treatment for severe haemolytic anaemia, SCD patients are more commonly begun on this treatment to decrease the frequency of acute painful episodes and acute chest syndrome. As both acute painful episodes and acute chest syndrome are thought to be vaso-occlusive complications that are associated with a lower degree of haemolysis (Kato, et al 2007), and may not be associated with PHT risk (Ataga, et al 2006, Gladwin, et al 2004), it is also conceivable that many patients begun on hydroxycarbamide for these indications may have lower TRVs as well as lower rates of progression compared to patients with higher degrees of haemolysis. However, any effects of hydroxycarbamide on SCD-associated PHT will be best defined in an adequately controlled clinical trial. The association of ACE inhibitors/ARBs therapy with an increase in TRV in our patient cohort was unexpected, although this finding is limited by the small number of patients on ACE inhibitors/ARBs in our patient cohort. Furthermore, with the known association of proteinuria and PHT (Ataga, et al 2010, De Castro, et al 2008), combined with the frequent use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs as treatment for proteinuria in SCD (Falk, et al 1992), this finding is not particularly surprising. While activation of the ACE-AngII-AT1R axis of the renin-angiotensin system may contribute to the pathophysiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension (Marshall 2003), therapy with ACE inhibitors/ARBs in patients with PHT has produced mixed results (Bradford, et al 2010). Despite these findings, this study was not designed to evaluate the effect of any therapeutic interventions. In addition, adherence to the various therapies was not evaluated and patients were often receiving more than one intervention during the period of follow-up, thus limiting any assessment of the effect of individual agents.

In summary, although this study was limited by the relatively small size of our patient cohort and our inability to obtain a measurable TRV in some participants, we found that TRV increases with time, albeit slowly. The rate of increase of the TRV appears to be even slower in patients being treated with hydroxycarbamide. As a subset of patients may experience more clinically meaningful increases in TRV, decisions about the frequency of screening should be individualized. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the rate of increase of TRV as well as the predictive markers of such increase in adult patients with SCD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants: HL79915 and HL094592. Support for this work was also provided by an award from the North Carolina State Sickle Cell Program. Acknowledgement: We acknowledge support from the Clinical and Translational Research Center at UNC, Chapel Hill (UL1RR025747).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: K.I. Ataga designed research, performed research, analysed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. P.C Desai performed research, analysed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. R. May performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. M. Caughey performed the echocardiograms and wrote the manuscript. A. Hinderliter interpreted the echocardiograms and wrote the manuscript. S. Jones collected the data and wrote the manuscript

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: KIA is a consultant to Pfizer and has served on the scientific advisory boards of HemaQuest and Adventrx.

References

- Ataga KI, Sood N, De Gent G, Kelly E, Henderson AG, Jones S, Strayhorn D, Lail A, Lieff S, Orringer EP. Pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Med. 2004;117:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataga KI, Moore CG, Jones S, Olajide O, Strayhorn D, Hinderliter A, Orringer EP. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with sickle cell disease: a longitudinal study. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataga KI, Brittain JE, Moore D, Jones SK, Hulkower B, Strayhorn D, Adam S, Redding Lallinger R, Nachman P, Orringer EP. Urinary albumin excretion is associated with pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease: potential role of soluble fms like tyrosine kinase 1. European Journal of Haematology. 2010;85:257–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barst RJ, Mubarak KK, Machado RF, Ataga KI, Benza RL, Castro O, Naeije R, Sood N, Swerdlow PS, Hildesheim M. Exercise capacity and haemodynamics in patients with sickle cell disease with pulmonary hypertension treated with bosentan: results of the ASSET studies. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:426–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford CN, Ely DR, Raizada MK. Targeting the vasoprotective axis of the renin-angiotensin system: a novel strategic approach to pulmonary hypertensive therapy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:212–219. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun M, Bourdoulous S, Couraud PO, Elion J, Krishnamoorthy R, Lapoumeroulie C. Hydroxyurea downregulates endothelin-1 gene expression and upregulates ICAM-1 gene expression in cultured human endothelial cells. Pharmacogenomics J. 2003;3:215–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn HF, Nathan DG, Dover GJ, Hebbel RP, Platt OS, Rosse WF, Ware RE. Pulmonary hypertension and nitric oxide depletion in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;116:687–692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carache S, Terrin TL, Moore RD. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anaemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro LM, Jonassaint JC, Graham FL, Ashley Koch A, Telen MJ. Pulmonary hypertension associated with sickle cell disease: clinical and laboratory endpoints and disease outcomes. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:19–25. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk RJ, Scheinman J, Phillips G, Orringer E, Johnson A, Jennette JC. Prevalence and pathologic features of sickle cell nephropathy and response to inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:910–915. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204023261402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca GH, Souza R, Salemi VM, Jardim CV, Gualandro SF. Pulmonary hypertension diagnosed by right heart catheterisation in sickle cell disease. Eur Respir J. 2011;39:112–118. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwin MT, Shelhamer JH, Ognibene FP, Pease-Fye ME, Nichols JS, Link B, Patel DB, Jankowski MA, Pannell LK, Schechter AN, Rodgers GP. Nitric oxide donor properties of hydroxyurea in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:436–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, Shizukuda Y, Plehn JF, Minter K, Brown B, Coles WA, Nichols JS, Ernst I, Hunter LA, Blackwelder WC, Schechter AN, Rodgers GP, Castro O, Ognibene FP. Pulmonary Hypertension as a Risk Factor for Death in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:886–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover RE, Corbett JT, Burka LT, Mason RP. In vivo production of nitric oxide after administration of cyclohexanone oxime. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:952–957. doi: 10.1021/tx990058v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell KL. Population Estimates of Sickle Cell Disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S512–S521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato GJ, Martyr S, Blackwelder WC, Nichols JS, Coles WA, Hunter LA, Brennan ML, Hazen SL, Gladwin MT. Levels of soluble endothelium-derived adhesion molecules in patients with sickle cell disease are associated with pulmonary hypertension, organ dysfunction, and mortality. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;130:943–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: Reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Reviews. 2007;21:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado RF, Barst RJ, Yovetich NA, Hassell KL, Kato GJ, Gordeuk VR, Gibbs JS, Little JA, Schraufnagel DE, Krishnamurti L, Girgis RE, Morris CR, Rosenzweig EB, Badesch DB, Lanzkron S, Onyekwere O, Castro OL, Sachdev V, Waclawiw MA, Woolson R, Goldsmith JC, Gladwin MT. Hospitalization for pain in patients with sickle cell disease treated with sildenafil for elevated TRV and low exercise capacity. Blood. 2011;118:855–864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-306167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RP. The pulmonary renin-angiotensin system. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:715–722. doi: 10.2174/1381612033455431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehari A, Gladwin MT, Tian X, Machado RF, Kato GJ. Mortality in adults with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307:1254–1256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olnes M, Chi A, Haney C, May R, Minniti C, Taylor J, Kato GJ. Improvement in hemolysis and pulmonary arterial systolic pressure in adult patients with sickle cell disease during treatment with hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:529–531. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, Lionnet F, Driss F, Loko G, Habibi A, Bennani S, Savale L, Adnot S. A Hemodynamic Study of Pulmonary Hypertension in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:44–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashankar FD, Carbonella J, Bazzy-Asaad A, Friedman A. Longitudinal follow up of elevated pulmonary artery pressures in children with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:736–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh AW, Hillen HF, Duits AJ. Levels of endothelial, neutrophil and platelet-specific factors in sickle cell anemia patients during hydroxyurea therapy. Acta Haematol. 1999;102:31–37. doi: 10.1159/000040964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yock PG, Popp RL. Noninvasive estimation of right ventricular systolic pressure by Doppler ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 1984;70:657–662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]