Abstract

Background

The benefits of expressive writing have been well documented among several populations, but particularly among those who report feelings of dysphoria. It is not known, however, if those diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) would also benefit from expressive writing.

Methods

Forty people diagnosed with current MDD by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV participated in the study. On day 1 of testing, participants completed a series of questionnaires and cognitive tasks. Participants were then randomly assigned to either an expressive writing condition in which they wrote for 20 min over three consecutive days about their deepest thoughts and feelings surrounding an emotional event (n=20), or to a control condition (n=20) in which they wrote about non-emotional daily events each day. On day 5 of testing, participants completed another series of questionnaires and cognitive measures. These measures were repeated again 4 weeks later.

Results

People diagnosed with MDD in the expressive writing condition showed significant decreases in depression scores (Beck Depression Inventory and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores) immediately after the experimental manipulation (Day 5). These benefits persisted at the 4-week follow-up.

Limitations

Self-selected sample.

Conclusions

This is the first study to demonstrate the efficacy of expressive writing among people formally diagnosed with current MDD. These data suggest that expressive writing may be a useful supplement to existing interventions for depression.

Keywords: Expressive writing, Major depressive disorder, Intervention, Written emotional disclosure

1. Introduction

Expressive writing is a technique whereby individuals engage in deep and meaningful writing about a traumatic or troubling event (Pennebaker and Beall, 1986). Over the past 25 years, a vast literature has documented robust physical and psychological benefits associated with expressive writing among several populations (e.g., undergraduate students, inmates, victims of partner abuse), that extend up to 6 months following intervention (Gortner et al., 2006; Koopman et al., 2005; Pennebaker and Francis, 1996; Richards et al., 2000). Compared to groups assigned to write about trivial or non-traumatic events, people who engage in expressive writing experience reduced medical visits (Pennebaker and Francis, 1996), improvements in immune function (Pennebaker et al., 1988), increases in antibody production (Petrie et al., 1995), increases in psychological wellbeing (Lepore, 1997; Murray and Segal, 1994) reduced anxiety (Sloan et al., 2005, 2007), and reduced depressive symptoms among both control and psychologically at-risk populations (Gortner et al., 2006; Graf et al., 2008; Koopman et al., 2005; Pennebaker and Chung, 2011; Sloan and Marx, 2004; Sloan et al., 2005, 2007, 2008; Stice et al., 2007). Of particular interest is that the mood-related benefits of expressive writing seem to be particularly notable among people who report higher levels of depression and anxiety (Baikie et al., 2012; Gortner et al., 2006; Koopman et al., 2005; Sloan et al., 2007). For example, women with high baseline depression, people scoring highly on suppression measures, and people who are likely to be suffering from mood disorders, especially benefit from expressive writing (Baikie et al., 2012; Gortner et al., 2006; Koopman et al., 2005). At this time, however, there has been no research examining the therapeutic qualities of expressive writing among people who have been formally diagnosed with current Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). The potential value of expressive writing as a supplement for existing treatments for depression is significant. Expressive writing is an activity that could be implemented by most any willing participant. Moreover, it is grounded in a rigorous, and comprehensive scientific tradition (Klein and Boals, 2001; Pennebaker and Beall, 1986; Sloan and Marx, 2004; Sloan et al., 2005). The sizable and meaningful effects observed in other populations (Smyth, 1998) suggest that expressive writing may well be an effective, time- and cost-efficient therapy to supplement existing treatments for depression (see Kazdin and Blase, 2011).

1.1. The current study

The purpose of this study was to determine if people diagnosed with current MDD would benefit from expressive writing just as non-clinical populations have been shown to benefit in the past. In addressing this question, the dependent measure we focused on was change in depressive symptoms over time—precisely the outcome that one would hope to see an effective intervention for depression influence over time. We tested whether three consecutive days of expressive writing would significantly reduce depression as indexed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ; Spitzer et al., 1999), two canonical and widely used measures of depressive symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Forty-four people diagnosed with current MDD were recruited for the study. Four participants (3 in the expressive group and 1 in the control group) dropped out of the study before its completion, leaving a total of 20 participants in each group. Twenty people were randomly assigned to the Expressive Writing (EW) group (15 females, 5 males, mean age=28 years), and 20 to the Control Writing (CW) group (16 females, 4 males, mean age=29 years). Data on ethnicity and socioeconomic status was not collected. Each participant underwent a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV (SCID; Fist and Gibbons, 1996) with a trained, advanced graduate student or Ph.D. level clinician, and was diagnosed with current MDD. Participants were recruited from the University of Michigan and the greater Ann Arbor area through advertisements posted on campus and in the surrounding community, and also on Craigslist and Facebook. Advertisements asked potential participants if they were feeling sad, down, or depressed; if they were interested in participating in research, they were asked to contact our lab via telephone or e-mail.

Participants met inclusion criteria if they were diagnosed with current MDD according to the SCID, and had no history of psychotic or bipolar disorder. All participants were tested in the experiment within 2 weeks of completing the SCID to ensure their diagnosis was current. Twenty-seven participants had co-morbid diagnoses (e.g., anxiety, phobia), and 15 were on medication for depression at the time of study (6 in EW; 9 in CW). All participants provided informed written consent as administered by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan, and were compensated a total of $160 dollars for their time.

2.2. Procedure

Testing always began on a Monday (referred to as “Pre”) with participants completing a series of questionnaires and cognitive measures including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ) (Spitzer et al., 1999).

On Tuesday through Thursday (Days 2–4 of testing), participants engaged in either expressive or control writing for a total of 20 min. The instructions for EW were administered following previous work (Pennebaker and Beall, 1986). Briefly, participants were asked to write about their deepest thoughts and feelings about an extremely important emotional issue that had affected them and their life. They were free to write about the same event on each day, or to write about different events. People in the control group were asked to write about how they organized their day. On the Friday (Day 5: Referred to as “Post”), participants repeated the questionnaire and cognitive measures (in alternate forms, where appropriate) that were administered on Day 1. These measures were again administered 4-weeks later (referred to as “Follow-up”). For the purposes of this communication, we only examined changes in depression scores on the BDI and PHQ.

2.3. Analysis parameters

A 2 (Group: EW vs. CW) × 3 (Time: Pre vs. Post vs. Follow-up) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed on the scores from the BDI and PHQ. Post-hoc analyses were performed where appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. BDI

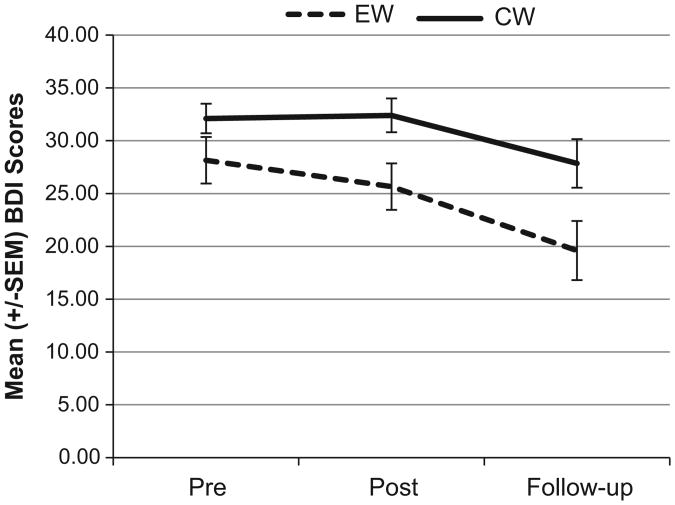

Relative to people in the CW condition, people in the EW group showed decreases in BDI depression scores immediately post test, and at 4-weeks post intervention. As seen in Fig. 1, repeated measures ANOVA on BDI scores revealed a significant effect of Time F(2, 38) = 10.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .21, and Condition F(1, 38) = 6.41, p=.02, ηp2 = .14, but no significant Interaction (F=1.03, p=.36). To further investigate the effect of time, repeated measures ANOVAs were run separately for the EW and CW groups. These analyses revealed that the effect of time was primarily driven by the EW group (EW group: F(2, 38) = 7.7, p=.002, ηp2 = .29 CW group F(2, 38)=3.1, p > .05, ηp2 = .14). Follow-up univariate analyses further examining group differences on BDI scores revealed no differences at baseline (F(1, 38)=2.17, p=.15, ηp2 = .05) but significant group differences post intervention (F(1, 38) = 6.37, p = .016, ηp2 = .14), and at follow-up (F(1, 38) = 5.01, p=.03, ηp2 = .12). Notably, by follow-up, people in the EW group, but not the CW group, had subclinical levels of depression as indexed by the BDI (<21). The same pattern of results was present when evaluating participants both on and off medication.

Fig. 1.

Mean (± SEM) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores before the intervention (pre), one day following the intervention (post), and 4 weeks after the intervention (follow-up).

3.2. PHQ

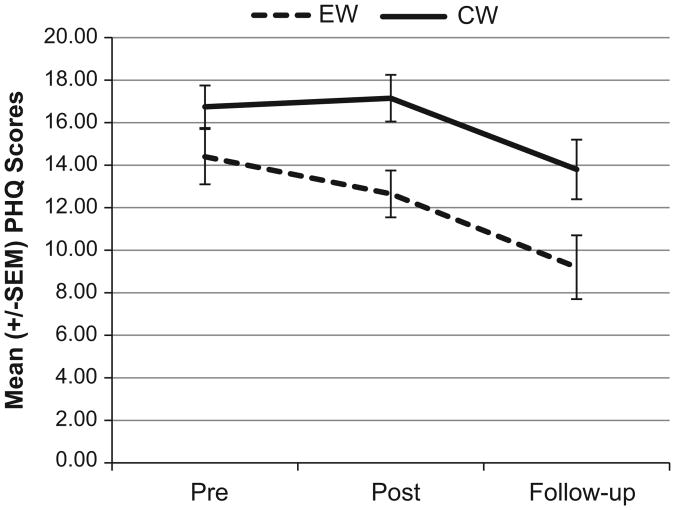

People in both the EW and CW groups showed decreases in PHQ depression scores post intervention, and 4-weeks follow-up. However, people in the EW group were significantly less depressed than their CW counterparts. As seen in Fig. 2, repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Time F(2, 38)=13.92, p < .011, ηp2 =.27, and Condition F(1, 38)=6.37, p=.016, ηp2=.15, but no Interaction (F=1.2, p=.31). To further explore the effect of Time, repeated measures ANOVAs were run for the EW and CW groups separately. These results revealed an effect of time in both groups (EW group: F(2, 38)=8.7, p=.001, ηp2=.32; CW group: F(2, 38)=5.8, p=.006, ηp2=.24). Follow-up univariate analyses further examining group differences in PHQ scores revealed no differences in depression at baseline (F(1, 38)=2.02, p=.16, ηp2=.05), but significant group differences post (F (1, 38)= 8.07, p=.007, ηp2=.17), and at follow-up (F(1, 38)=4.85, p=.034, ηp2=.12). Again, people in the EW group had subclinical depression scores on the PHQ by the end of the study (<10). The same patterns of results were found when evaluating those both on, and off medication.

Fig. 2.

Mean (± SEM) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ) scores before the intervention (pre), one day following the intervention (post), and 4 weeks after the intervention (follow-up).

3.3. Summary

In summary, analysis of both the BDI and PHQ data revealed that the EW group had lower depression scores immediately following the intervention, and that this persisted to the 4-week follow-up. The BDI data also revealed a significant effect of time, which was driven by the EW group. While the effect of time was present for both the EW and CW group in the PHQ data, the effect-size was larger in the EW group.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of expressive writing among people formally diagnosed with current Major Depressive Disorder. It was unclear a priori whether having people write expressively and explore their private thoughts and feelings would reduce depressive symptoms, as it does in populations of dysphoric individuals, or propel the ruminative process and worsen the depression. Consistent with earlier work, expressive writing reduced depression scores among people diagnosed with current MDD. Compared to a group assigned to write about daily events, people with MDD in the EW group showed significant reductions in depression scores on both the BDI and the PHQ immediately following 3 days of writing, and these differences persisted 4-weeks later. Importantly, there were no baseline differences between EW and CW group in age, gender or severity of depression.

Examination of our BDI data showed an effect of Time that was driven by the EW group. The effect of Time was also present in the PHQ data, but in this case both groups showed a significant effect, although it was stronger in the EW group (EW ηp2=.31 vs. CW ηp2=.24). Considering that the EW group had significantly lower depression scores than the CW group immediately following the intervention, and again at 4-weeks post intervention, we interpret this effect of Time in the CW group to reflect the standard course of depression. Symptoms gradually worsen and remediate even when untreated.

These data are clinically meaningful. On average, the EW group dropped to nearly 9 points on the BDI, and over 5 points on the PHQ. Indeed, by the end of the study, people in the EW group had subclinical scores on both of these measures. Anecdotally, participants remarked about feeling better. On the final day of expressive writing, one participant even wrote about how much better she felt, and wondered if these few days of writing really could possibly have had an impact. Both the statistical significance and anecdotal evidence strongly support the possibility that incorporating expressive writing into a treatment plan for MDD could positively impact outcomes. Moreover, a recent paper Kazdin and Blase (2011) highlighted the necessity of developing simple and cost-efficient methods to treat anxiety and depression. Expressive writing does exactly this: it is readily accepted by patients, and is also time- and cost-effective. Moreover, for the first time, the data presented in this paper provide experimental support for the efficacy of expressive writing among those with MDD.

These preliminary data are encouraging, but more work is needed not only to replicate these results, but to examine individual differences in susceptibility to EW effects. Our data suggest that at the group level, expressive writing is effective in MDD. It may be, however, that some patients are more or less likely to respond to expressive writing. From a clinical perspective, this knowledge is important.

Finally, the mechanisms of expressive writing are unknown at this time. Others have hypothesized expressive writing to be driven by individual and social disinhibition, habituation to emotional stimuli, catharsis, the translation of emotions into language, and changes in working memory (for review, see Pennebaker and Chung, 2011). Future work examining the mechanisms of individual differences in MDD may prove insightful from an academic and clinical perspective.

4.1. Limitations

While these preliminary data are encouraging, there are some limitations. The sample size was modest and self-selected, and many participants had co-morbidities and were taking medications. Our sample is also primarily female. While both the EW and CW group contained similar numbers of males (5 and 4, respectively) it is possible that gender is an important factor in the efficacy of expressive writing in MDD.

4.2. Conclusion

This is the first study to demonstrate that the benefits of expressive writing extend to people diagnosed with current MDD. In our study, there were no baseline group differences in severity of depression. Importantly, people in the EW group, who wrote for just 20-min a day for three consecutive days, had significantly lower depression scores than their control counterparts just one day after the intervention. Moreover, 4-weeks later, the EW group still had significantly lower (and subclinical) depression scores than the control group. These data suggest that expressive writing could be used to supplement existing interventions of depression. It is time- and cost-efficient, and is accessible to any person capable of expressive output.

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank all the people who participated in the study. We also thank Alexa Erickson and Catherine Cherny for their help with data collection; Sue Li for her help in processing data; Phillip Cheng, Hyang Sook Kim, Teresa Nguyen and Savanna Mueller for diagnostic interviewing.

Role of funding source: This work was supported by NIMH grant MH060665 to John Jonides. This work was also supported by the University of Michigan Advanced Rehabilitation Research Training Program (Grant #H133P090008) funded by the National Institute on Disability Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services (OSERS) of the U.S. Department of Education, Washington, DC. The grants were used to pay the post-doctoral fellow's stipend (Katherine M. Krpan), research assistants' salary, and the cost of running the experiment.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors' have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Baikie KA, Liesbeth G, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: an online randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fist MB, Gibbons M. SCID-101 for DSM-IV Training Video for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gortner EM, Rude S, Pennebaker J. Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37(3):292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf M, Gaudiano B, Geller P. Written emotional disclosure: a controlled study of the benefits of expressive writing homework in outpatient psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. 2008;18(4):389–399. doi: 10.1080/10503300701691664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psycotherapy resarch and practice to reduce teh burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein K, Boals A. Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General. 2001;130(3):520–533. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman C, Ismailji T, Holmes D, Classen C, Palesh O, Wales T. The effects of expressive writing on pain, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(2):211–221. doi: 10.1177/1359105305049769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ. Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(5):1030–1037. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EJ, Segal DL. Emotional processing in vocal and written expression of feelings about traumatic experiences. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1994;7(3):391–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02102784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95(3):274–281. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing and its links to mental and physical health. In: Friedman HS, editor. Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Francis ME. Cognitive, emotional and language processes in disclosure. Cognition and Emotion. 1996;10:621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(2):239–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW, Davison KP, Thomas MG. Disclosure of trauma and immune response to a hepatitis B vaccination program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(5):787–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Beal WE, Seagal JD, Pennebaker JW. Effects of disclosure of traumatic events on lillness behavior among psychatric prison inmates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(1):156–160. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D, Marx B. A closer examination of the structured written disclosure procedure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):165–175. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D, Marx B, Epstein E. Further examination of the exposure model underlying the efficacy of written emotional disclosure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):549–554. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D, Marx B, Epstein E, Dobbs J. Expressive writing buffers against maladaptive rumination. Emotion. 2008;8(2):302–306. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D, Marx B, Epstein E, Lexington J. Does altering the writing instructions influence outcome associated with written disclosure? Behavior Therapy. 2007;38(2):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burton E, Bearman S, Rohde P. Randomized trial of a brief depression prevention program: an elusive search for a psychosocial placebo control condition. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(5):863–876. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]