Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder (BD) is associated with inhibitory deficits characterized by a reduced ability to control inappropriate actions or thoughts. While aspects of inhibition such as exaggerated novelty-seeking and perseveration are quantified in rodent exploration of novel environments, similar models are rarely applied in humans. The human Behavioral Pattern Monitor (hBPM), a cross-species exploratory paradigm, has identified a pattern of impaired inhibitory function in manic BD participants, but this phenotype has not been examined across different BD phases. The objective of this study was to determine if euthymic BD individuals demonstrate inhibitory deficits in the hBPM, supporting disinhibition as an endophenotype for the disorder.

Methods

25 euthymic BD outpatients and 51 healthy comparison subjects were assessed in the hBPM, where activity was recorded by a concealed videocamera and an ambulatory monitoring sensor.

Results

Euthymic BD individuals, similar to manic subjects, demonstrated increased motor activity, greater interaction with novel objects, and more frequent perseverative behavior relative to comparison participants. The quantity of locomotion was also reduced in BD individuals treated with mood stabilizers compared to other patients.

Limitations

Low sample size for treatment subgroups limits the evaluation of specific medication regimens.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that BD is distinguished by both trait- and state-dependent inhibitory deficits optimally assessed with sophisticated multivariate measures. These data support the use of the hBPM as a tool to elucidate the effects of BD across various illness states, facilitate the development of BD animal models, and advance our understanding of the neurobiology underlying the disorder.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, inhibition, euthymic, behavioral pattern monitor, exploration, impulsivity

1. Introduction

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a prevalent neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by episodes of mania and associated with significant impairment in social, occupational, and family life (Rosa et al., 2010). One of the core symptoms of the illness is an inability to appropriately inhibit actions and thought, often manifesting as a pattern of impulsivity and amplified novelty-seeking behavior (Akiskal and Benazzi, 2005; Goodwin and Jamison, 1990). While impaired inhibition is typically associated with discrete episodes of mania, an accumulating body of evidence indicates that inhibitory deficits persist across all phases of the disorder, including periods of remission (Bora et al., 2009; Lombardo et al., 2012). Euthymic BD individuals exhibit poor response inhibition and increased perseverative responding compared to healthy subjects on tests such as the Stroop and Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) (Altshuler et al., 2004; Martinez-Aran et al., 2004a; Zubieta et al., 2001). Similar inhibitory deficits also occur in first-degree BD relatives and are proposed to represent an endophenotype of the disorder (Bora et al., 2009). Self-reported impulsivity on measures such the Barrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS), which may reflect a facet of disinhibition, is also elevated in BD individuals regardless of mood state (Swann et al., 2009; Swann et al., 2003). However, despite the use of self-report metrics and traditional neuropsychological assessment, relatively little work has been conducted to objectively quantify aspects of BD inhibitory deficits such as dysregulated exploratory behavior, including interaction with novel stimuli (Henry et al., 2010). The dearth of effort in this direction is particularly surprisingly given the central importance of these symptoms in BD and the attempts to recreate these symptoms in animal models utilizing measures of motor activity and object interaction (Young et al., 2011a).

To address this paucity of research, we developed the human Behavioral Pattern Monitor (hBPM), the first cross-species translational tool designed as an analog to the rodent BPM paradigm that was established as an elaboration of the classic open field test (Geyer et al., 1986; Perry et al., 2009; Young et al., 2007). The hBPM utilizes a multivariate approach to quantify the total amount of motor activity, the structure and spatial organization of subject movement, and the exploration of novel objects placed around the room (Henry et al., 2011; Minassian et al., 2009; Minassian et al., 2011; Perry et al., 2009). We have observed that inpatient BD individuals in a manic state exhibit a signature pattern of higher motor activity, abnormally straight movements, and elevated object interactions relative to non-bipolar healthy comparison participants (Perry et al., 2009). Manic BD participants also demonstrate a unique tendency to engage in more socially disinhibited forms of novel object interaction compared to controls or inpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia, including wearing a mask or goggles (Perry et al., 2010). Additional work showed that medicated BD inpatients exhibit consistently elevated hBPM activity relative to healthy comparison subjects during repeated testing over a three-week treatment period (Minassian et al., 2011). Patients maintained a moderate to severe manic state during all three test sessions, indicating that the hBPM represents a reliable paradigm to measure disinhibition during this acute phase of the disorder. Similar to our human findings, hyperdopaminergic mice with reduced expression of the dopamine transporter (DAT), a putative model of BD, exhibit a comparable pattern of increased locomotion, repetitive straight-line movements, and increased exploration of holes in the mouse behavioral pattern monitor (mBPM) (Perry et al., 2009; Young et al., 2010). While we have successfully demonstrated the cross-species application of the hBPM, previous work has not determined if the phenotype of disinhibition observed in BD mania is primarily a state- or trait-dependent characteristic.

The purpose of the current study was to compare inhibitory deficits in the hBPM in a cohort of euthymic BD outpatient participants and a non-bipolar comparison group. Based on existing findings supporting the hypothesis that disinhibition represents an endophenotype for the disorder (Bora et al., 2009), we hypothesized that BD individuals in a euthymic state would continue to demonstrate inhibitory deficits evidenced by greater object interaction and perseveration relative to healthy individuals. While prior work with the hBPM has focused on BD abnormalities during acute episodes of severe illness, our primary objective was to determine if this tool can be utilized effectively to quantify stable indicators of pathology, similar to traditional self-report and neuropsychological measures.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

This study was approved by the UC San Diego Human Research Protections Program (Institutional Review Board). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Twenty-five SCID (Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV) diagnosed BD participants between the age of 18 and 55 were recruited from the outpatient psychiatric clinic at the University of California (UCSD) Medical Center. Participants did not exhibit current mania, hypomania, or major depression when participating in the study as determined by SCID criteria and scored ≤ 12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and ≤ 16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Tohen et al., 2000). The mean YMRS and HDRS scores for the BD cohort were approximately 5 and 7, respectively (see Table 1). The definition of euthymia in BD has come under recent scrutiny in the past decade, since many studies report the presence of subsyndromal symptoms in stable patients and different cut-off scores have been applied by various researchers (Bonnin et al., 2012). Some recent reports propose that remission should be defined more strictly by stringent standards, including YMRS scores below 4 or HDRS scores below 7 (Berk et al., 2008; Chengappa et al., 2003). While our sample was selected using more liberal criteria, we addressed this question by conducting subsequent analyses with a subset of BD participants with YMRS score ≤ 3 or HDRS scores ≤ 6 as described below. 51 non-bipolar healthy comparison (HC) participants who did not meet criteria for an Axis I disorder were recruited from advertisements in the San Diego community. The two groups were matched for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and equivalent premorbid IQ as assessed by the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) (Dunn, 1997), while BD participants had slightly higher education compared to HC (Table 1). General psychopathology was quantified with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Opler et al., 2007). A subset of HC participants received the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) instead of the HDRS. The majority of BD participants were taking mood stabilizers and/or atypical antipsychotics. The most common antipsychotic medications prescribed were risperidone and aripiprazole, and the most common mood stabilizers prescribed were valproate, lamotrigine, and lithium (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic factors, symptom rating scales, and medication status are shown for healthy comparison (HC, n = 51) and bipolar disorder (BD, n = 25) participants. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test results are presented as age-adjusted standard scores. 30 HC participants were administered the BDI, while 21 received the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), as did all the BD participants; the statistical difference shown here includes only the HDRS scores. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

| Parameter | HC | BD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.0 ± 1.7 | 38.1 ± 1.4 | |

| Gender | 31 M, 20 F | 10 M, 15 F | |

| Education (years) | 13.7 ± 0.2 | 14.7 ± 0.4* | |

| Body Mass Index | 27.5 ± 1.2 | 29.2 ± 1.5 | |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 99.0 ± 1.7 | 100.2 ± 2.8 | |

| YMRS | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.7*** | |

| HDRS (21 HC) | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.8** | |

| BDI (30 HC ) | 2.2 ± 1.0 | ||

| PANSS Total | 36.7 ± 0.8 | 45.4 ± 1.7*** | |

| PANSS positive subscale | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 10.6 ± 0.5** | |

| PANSS negative subscale | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | |

| BD age of onset | -------- | 28.0 ± 1.7 | |

| BD duration of illness (years) | -------- | 10.1 ± 1.4 | |

| BD number of hospitalizations | -------- | 2.4 ± 0.5 | |

| Medication Type (number of patients) | -------- | ||

| Mood stabilizer alone | 10 | ||

| Antipsychotic alone | 6 | ||

| Antipsychotic plus mood stabilizer | 5 | ||

| Unmedicated | 3 | ||

| On lithium | 5 | ||

| On valproate | 5 | ||

| On lamotrigine | 4 | ||

| On risperidone | 3 | ||

| On aripiprazole | 6 | ||

Asterisks indicate significant group differences;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

Participants were excluded for: 1) current alcohol or substance dependence; 2) a history of neurological conditions or head trauma; 3) treatment with electroconvulsive therapy; 4) stroke, myocardial infarction, or cardiac disease; and 5) a positive result for illicit drugs on a urine toxicology screen. All subjects provided written informed consent to the current protocol approved by the UCSD institutional review board.

2.2 Human behavioral pattern monitor

The hBPM consists of a 3.5 m by 4.9 m rectangular room that contains several items of furniture, including two bookcases, several tall filing cabinets, a corkboard mounted on the wall, and a short storage chest, but no chairs. A number of small objects were placed throughout the room to stimulate exploration and invite participant interaction (Henry et al., 2011; Minassian et al., 2011; Perry et al., 2009). These items were selected to meet several criteria, including being safe, colorful, tactile, and manipulable (Pierce and Courchesne, 2001); they include a feather mask that could be worn, a kaleidoscope, finger puppets, and a paddle ball game. Participant activity in the room was monitored and recorded by a camera concealed in the ceiling that is equipped with a fish-eye lens capable of viewing the entire room. Digitized videos sampled at 30 frames per second were stored on a computer in an adjacent room for subsequent analysis (Perry et al., 2010).

Prior to entering the hBPM, participants were fitted with an ambulatory monitoring device worn on the torso that quantifies motor activity via a triaxial accelerometer (Hidalgo, 2010; Vivometrics, 2002). Encrypted data were stored on a removable memory card and subsequently extracted and analyzed with the Vivosense™ proprietary PC-based software. Mean acceleration values were generated from a filtered summation of movement on the x,y, and z axes while incorporating force effects due to gravity. After being fit with the monitor, individuals were placed in the hBPM for 15 minutes without explicit directions except to wait for the experimenter to prepare another task.

2.3 Data Collection

The hBPM provides a multivariate assessment of exploratory behavior relevant to the concept of inhibition, including quantifying the amount of motor activity, the sequence and structure of locomotion, and interaction with novel objects in the room. Digitized video images were subjected to frame-by frame analysis with proprietary software (TopScan 1.0; Clever Systems Inc, Washington, DC) that generates x–y coordinates of subjects within a 720 by 480 pixel grid. The x–y data were initially processed with a low-pass Butterworth filter to remove instrumental noise. The total distance traveled in the room was calculated by integrating the x–y coordinates along the subject’s path using only movement increments beyond a 10 pixel radius to define movement. The quantity of motor activity was also estimated by the number of sector transitions performed by participants across a 64-sector grid with 8 pixel boundaries as previously described (Perry et al., 2010). Movement structure was evaluated with two measures, spatial d and the spatial coefficient of variation (CV). Spatial d, measured between values of 1 and 2, indicates the extent to which a subject travels in a straight line (close to 1) or adopts a more convoluted, meandering path, such as very localized, circumscribed movements (close to 2). This measure is calculated by plotting the successive x–y coordinates of the path traveled against varying lengths of measuring resolutions (e.g., measuring the distance traveled with a small versus large ruler) (Paulus and Geyer, 1991). Values at either end of this range may indicate perseverative behavior, as indicated by the tendency of manic BD individuals and DAT KD mice to engage in abnormally straight and repetitive patterns of activity (Perry et al., 2009). Spatial CV describes variation in the pattern of transitions among the 64 sectors in the hBPM. Repeated transitions between the same sectors coupled with few transitions elsewhere reflects a more consistent pattern of locomotion resulting in higher CV values (Geyer et al., 1986), while more diverse activity across sectors throughout the room will result in lower CV values.

Object interactions in the hBPM were quantified manually by trained raters blind to group condition who evaluated participant exploration in one-second increments during the video recording. Video rater reliability was assessed over the course of the study and kappa reliability coefficients for rater-coded measures ranged from 0.91 to 0.96 (Perry et al., 2010). To assess object interaction, we quantified: 1) the total number of object interactions, defined as deliberate physical contact with a novel object with any part of the body, e.g., hand or foot; 2) multiple object interactions (MOI), instances when a participant interacts with more than one object at the same time; and 3) perseverative interactions, the number of repeated interactions with the same objects. Our previous work with the hBPM indicates that manic BD subjects are characterized by a unique tendency to investigate the closed drawer of the small storage chest and wear the mask (Perry et al., 2010), indicating a propensity to engage in socially inappropriate activities (e.g., opening a private drawer or wearing an item that may belong to another person). These specific measures were thus quantified in the current study to determine if this phenomenon continues to persist in euthymic individuals.

2.4 Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS. Data were examined for normality and homogeneity of variance. Initial assessment indicated that several hBPM variables exhibited skewed and kurtotic distributions; hence a log transformation was applied to the acceleration data and square root transformations were applied to distance traveled, sector transitions, and spatial CV, limiting skew and kurtosis within a range of −1 to +1. Acceleration data were not collected for two HC participants due to equipment malfunction. Group effects on motor quantity and structure were analyzed with univariate ANOVAs for the 15-minute session and education was included as a covariate due to a small but significant group difference in this variable. To determine if locomotion varied over time, data were calculated separately for each of three 5 minute epochs within the full session. Mixed ANOVAs were conducted for each variable with group as a between-subjects factor and epoch as a repeated measure. Post-hoc differences were assessed with Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons. In addition to our primary analyses, we also performed univariate tests to compare HC participants to subsets of our BD group with YMRS scores ≤ 3 (n = 12) or HDRS scores ≤ 6 (n = 12) to address potential effects of ongoing subsyndromal symptoms. Approximately half of the participants in this study were tested with a desk placed in the hBPM in addition to the furniture described above. Preliminary findings indicated that the absence or inclusion of this piece of furniture did not interact with group status for any of the hBPM measures, so both conditions were combined for all data analyses.

The data distribution for the number of object interactions was distinguished by considerable positive skew and a high number of low integer values. This measure was thus treated as count data and analyzed with a log link negative binomial regression model where the scale parameter was estimated from deviance and a robust estimator used for the covariance matrix (Hilbe, 2007). Comparison with linear and Poisson regression models indicated that the negative binomial model exhibited superior goodness of fit based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and had a Pearson chi-square value/df ratio of 1.2. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) with the negative binomial model were used subsequently to evaluate repeated-measures object interactions across epochs, since the GEE is appropriate to assess longitudinal, non-normal data where successive measures may be correlated (Hardin and Hilbe, 2003). The overall quantity of both multiple and perseverative object interactions was low, so these two measures were assessed as a dichotomous variable (present or absent for each participant) and evaluated with Fisher’s Exact Test.

The association between hBPM variables, symptom rating scales, and BD illness characteristics (YMRS total score and individual symptom ratings, HDRS, PANSS total score, positive and negative subscores, BD onset and duration of illness) was examined with bivariate Pearson r correlations while Spearman’s rho was used for the object interaction data; the Bonferroni correction was applied for the multiple correlation analyses to reduce the probability of a Type I error. To assess the potential influence of medication, univariate analyses were performed to compare the main effects of mood stabilizer or antipsychotic treatment on hBPM measures.

3. Results

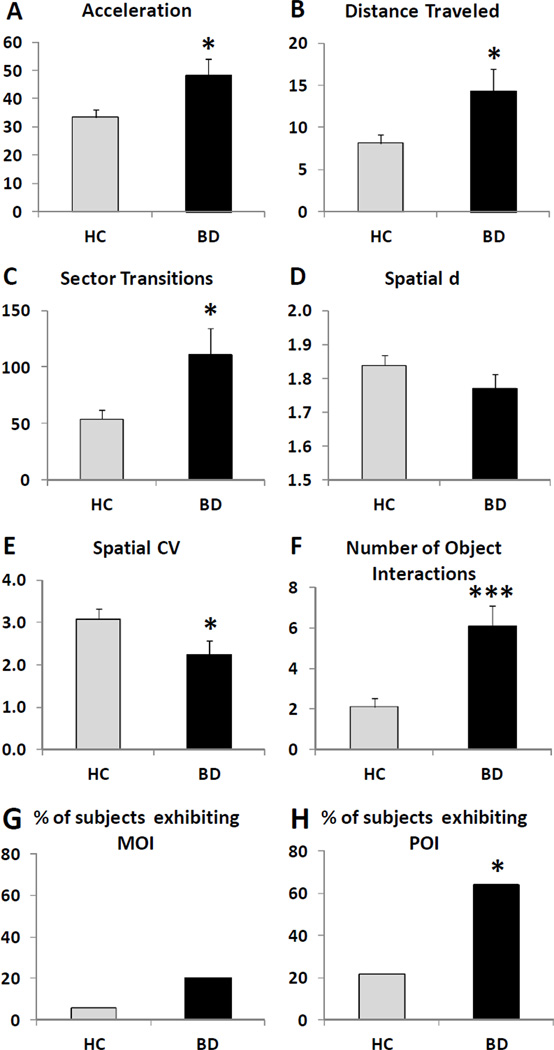

Analyses of the 15-minute hBPM session indicated that BD participants exhibited significantly greater acceleration (F(1,71) = 6.4, p<0.05), distance traveled (F(1,73) = 4.8, p<0.05), sector transitions (F(1,73) = 6.7, p<0.05), and reduced spatial CV (F(1,71) = 5.0, p<0.05) compared to HC subjects (Figure 1). No difference was observed for spatial d and there was no main effect or interaction with education for any variable. Repeated-measures ANOVA did not indicate any interaction between the 5-minute epoch intervals and group condition for either the quantity or structure of motor activity.

Figure 1.

hBPM data for healthy comparison (HC, n = 51) and bipolar disorder (BD, n = 25) participants during the 15-minute session, including acceleration (A), distance traveled (B), sector transitions (C), spatial d (D), spatial CV (E), number of object interactions (F), and the percent of participants who engaged in multiple object interactions (MOI) (G) or perseverative object interactions (POI) (H). Data are represented as means ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant group differences; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

BD participants engaged in significantly more object interactions relative to HC over the 15-minute span (Wald Chi-square = 14.1, df=1, p < 0.001) (Figure 1F). Assessment of object interactions over time with GEE indicated a main effect of group (Wald Chi-square = 18.8, df=1, p < 0.001) and epoch (Wald Chi-square = 32.1, df=2, p < 0.001), but no significant interaction. Post-hoc comparisons revealed that all subjects exhibited fewer object interactions in epochs 2 and 3 relative to the first 5 minutes (p < 0.001), and this pattern occurred for both HC and BD participants. Few participants in either group opened the drawer (2 HC, 4 BD) and the proportion did not differ significantly between the groups. None of the participants wore the mask. Similarly, the number of individuals demonstrating multiple object interactions was very low and did not differ between HC and BD subjects (Fig. 1G). However, a higher percentage of BD subjects demonstrated perseverative object interactions compared to HC (p < 0.05) (Fig 1H).

The results for the subset of BD participants with low YMRS scores (≤ 3) were similar to the complete cohort, with significantly greater acceleration (F(1,59) = 4.5, p<0.05), distance traveled (F(1,61) = 5.9, p<0.05), sector transitions (F(1,61) = 8.0, p<0.01), spatial CV (F(1,60) = 6.0, p<0.05), and object interactions (Wald Chi-square = 16.3, df=1, p < 0.001) compared to the HC group. BD subjects with lower HDRS scores (≤ 6) also exhibited strong trends toward higher acceleration (F(1,59) = 3.6, p=0.06), sector transitions (F(1,61) = 3.0, p=0.09), and showed significantly greater object interactions (Wald Chi-square = 9.0, df=1, p < 0.01) relative to HC subjects.

We did not observe any significant correlations between YMRS ratings or HDRS scores and hBPM measures for HC or BD participants. BD illness characteristics (age of onset, illness duration, number of hospitalizations) were also unrelated to activity in the hBPM paradigm. There were trends towards positive correlations between the total PANSS score and distance traveled (r = 0.41, p = 0.04) and sector transitions (r = 0.43, p = 0.03) in BD participants, as well as acceleration (r = 0.31, p = 0.03) and distance traveled (r = 0.30, p = 0.04) in HC individuals.

BD subjects currently treated with a mood stabilizer (n = 15) exhibited significantly lower acceleration compared to BD individuals not treated with this class of medication (n = 10) (F(1,23) = 10.1, p<0.01), and also demonstrated trends towards lower distance traveled (F(1,23) = 3.8, p=0.06) and fewer sector transitions (F(1,23) = 3.4, p=0.08) (Figure 2). In contrast, no significant differences were observed for motor structure or object interactions. To follow up on this finding, we compared these two groups on demographic and symptom scales; they did not differ on age, gender, YMRS score, HDRS score, BD age of onset, or number of hospitalizations, but the BD participants taking mood stabilizers had lower PANSS scores (42.4 vs. 50.3, p < 0.05) and shorter duration of illness (7.4 vs. 14.2 years, p < 0.05) relative to the non-mood stabilizer group. We subsequently compared acceleration between the two medication groups using ANOVAs that included these variables as covariates. The effect of mood stabilizer treatment remained significant even when accounting for variance due to PANSS scores, (F(1,22) = 6.0 p<0.05) or illness duration (F(1,22) = 7.5, p<0.05). We did not observe any significant differences between BD participants who were treated (n = 11) or not treated (n = 14) with antipsychotic medication.

Figure 2.

15 minute hBPM data for BD participants currently treated with mood stabilizers (BDms, n = 15) compared to BD participants not treated with mood stabilizer medication (BDnt, n = 10), including acceleration (A), distance traveled (B), sector transitions (C), spatial d (D), spatial CV (E), number of object interactions (F). Data are represented as means ± SEM. ** p < 0.01; † p < 0.10.

4. Discussion

Inhibitory deficits represent an integral feature of BD and are proposed to underlie many symptoms linked to the disorder, including impulsivity and novelty-seeking behavior (Akiskal and Benazzi, 2005; Goodwin and Jamison, 1990). Our findings with the hBPM indicate that euthymic BD participants, similar to manic BD participants, exhibit increased motor activity, greater interaction with novel stimuli, and more perseverative object interactions compared to HC subjects, supporting the premise that inhibitory deficits may constitute an endophenotype of BD (Bora et al., 2009). These data also reveal an intriguing pattern of more subtle differences between manic and euthymic BD participants, since euthymic individuals did not tend to display violations of social boundaries (opening a private drawer, wearing a mask that may belong to another person) or engage in multiple object interactions. In contrast, approximately half of manic inpatient BD subjects wore an item or opened a drawer in the hBPM, in distinction to schizophrenia inpatients who did relatively little of either, suggesting that these measures may represent a specific hallmark of mania (Perry et al., 2010). Euthymic participants also demonstrated relatively fewer object interactions (mean = 6) compared to previously reported levels in manic inpatients (mean = 25) (Perry et al., 2010) and did not show decreased spatial d, but did exhibit lower CV relative to HC, indicating a more random distribution of movements between various sectors in the room. These data may reflect a nuanced combination of state- and trait-dependent effects that emerge only with a comprehensive multivariate assessment. While neurocognitive impairment exists across the BD spectrum (Martinez-Aran et al., 2004b), manic episodes are defined by exacerbated deficits in behavioral self-regulation, including socially disinhibited hypersexuality and risky financial decisions (Goodwin and Jamison, 2007). Manic and hypomanic individuals also exhibit impaired inhibitory control relative to other BD states on tests such as the WCST (Ryan et al., 2012), while BD severity is associated with the degree of response inhibition (Swann et al., 2009). It is interesting to note that behavioral disinhibition in young children (age 2–6), quantified by increased approach to unfamiliar stimuli and greater vocalizations, was also elevated in the offspring of BD parents relative to healthy controls and proposed as a predictor of subsequent psychopathology (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2003; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2006). In contrast, many studies of adult BD rely on self-report measures to predict clinical outcome and determine the proximal causes of affective relapse (Proudfoot et al., 2012). Most clinical trials for BD treatments have also focused primarily on the amelioration of mood symptoms, typically defined by a 50% decrease in the YMRS score (Smith et al., 2007), while relatively little work has examined therapy efficacy for cognitive impairment (Torres et al., 2010a; Torres et al., 2010b). Therefore, the hBPM could be utilized as a tool to provide objective measures of behavioral regulation that signal transitions between euthymia and mania, evaluate individuals who may be at risk for developing the illness, and determine the effect of BD treatments on inhibitory deficits associated with high risk behaviors.

We did not observe any significant correlations between the YMRS or HDRS ratings and activity in the hBPM, but the total PANSS score was weakly associated with the quantity of hBPM locomotion in both BD and HC participants. BD participants with particularly low YMRS or HDRS scores also continued to show greater motor activity and object interactions relative to the HC group. These findings are congruent with earlier work reporting inconsistent associations between observer-scored rating scales and hBPM measures (Minassian et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2010). The total YMRS score was not significantly associated with either object interactions (Perry et al., 2010) or acceleration (Minassian et al., 2009) in manic BD subjects, although the elevated mood item on the YMRS scale was correlated with both measures (Minassian et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2010). Discriminant function analyses indicate that hBPM measures appear to distinguish diagnostic differences better than assessment with the YMRS and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Perry et al., 2009); other work has shown that the total PANSS and positive PANSS subscale scores were correlated with higher object interactions in a non-bipolar cohort (Henry et al., 2011). The current findings in our euthymic BD sample support the premise that inhibitory deficits persist in the absence of acute manic or depressive symptoms and that objective measures of activity may be more sensitive than self-report and observer ratings of psychomotor behavior (Bussmann et al., 1998; Dubbert et al., 2006; Sims et al., 1999).

Relative to BD participants not taking mood stabilizers, BD participants treated with mood stabilizers exhibited significantly decreased acceleration and trends towards reduced distance traveled and fewer sector transitions, but did not differ in spatial d, spatial CV, or object interactions. This result differs from earlier studies that did not find any effect of lithium, valproate, or risperidone on hBPM activity in acutely hospitalized BD or schizophrenia subjects, although one report observed that valproate-treated inpatients exhibited more object interactions (Perry et al., 2009). While the low sample size in the current sample (4–5 BD patients were taking either lithium, valproate, or lamotrigine, respectively) precludes a comprehensive analysis of individual medication effects, these data signify that chronic treatment with mood stabilizers in a stable outpatient cohort may ameliorate hyperactivity, but not affect motor structure or novelty-seeking. Our data are strikingly similar to a recent report indicating that chronic valproate treatment in DAT knockdown (KD) mice significantly reduced motor activity, but did not change spatial d or exploratory behavior in the mBPM, the rodent equivalent of the hBPM (van Enkhuizen et al., 2012). Previous work illustrated that untreated DAT KD mice, similar to manic BD patients, exhibit hyperactivity, lower spatial d, and increased hole exploration (analogous to human object interaction) in the mBPM, consistent with the hypothesis that dopaminergic abnormalities may mediate the same phenotype in mania (Perry et al., 2009). Although the therapeutic mechanisms of valproate remain speculative, the drug is known to increase DAT expression, most notably after chronic treatment (Wang et al., 2007), which may ameliorate BD symptoms impacted by this neurotransmitter system. One recent clinical study reported that unmedicated BD individuals in a euthymic or depressed state exhibited a significant decrease in striatal DAT expression compared to healthy subjects (Anand et al., 2011), supporting the premise that dysregulated dopaminergic signaling may occur across all states of the disorder. Alterations in striatal dopamine synthesis and receptor availability have also been associated with impaired response inhibition, greater impulsivity, and risky behaviors such as gambling, illustrating the relevance of this system to BD inhibitory deficits (Ghahremani et al., 2012; Lawrence et al., 2013). The fact that mood stabilizer treatment appears to affect general motor activity, but not measures such as object interaction in patients, may reflect the limitations of current therapies in addressing the neurocognitive deficits that persist in BD. Recent studies report that increased hBPM object interactions in a non-BD cohort were associated with poor performance on the WCST, while increased holepokes in the mBPM were associated with greater risk preference in a mouse version of the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) (Henry et al., 2011; Young et al., 2011b). These data imply that BD treatments that normalize both hyperactivity and increased specific exploration might better alleviate the cognitive dysfunction as well as the affective pathology linked to the disorder.

Our understanding of the neuropathology that underlies BD is limited by the dearth of validated animal models and the inherent difficulty in creating representations of a cyclic disorder marked by diverse and multifaceted symptoms. BD mania is typically modeled in rodents by administration of stimulants such as amphetamine or conditions such as sleep deprivation (Henry et al., 2010), but determining the neurobiological pathways that explicate other BD phases such as euthymia remains a challenge. The findings with the hBPM and DAT KD mice in the mBPM indicate that we are able to quantify similar cross-species behaviors putatively mediated by the same neurotransmitter abnormalities and comparably altered by the same type of medication. The phenotype observed in the current cohort of euthymic BD participants will assist in the development of preclinical BD models that span the spectrum of the disorder, expanding the existing repertoire of rodent representations of mania. Future hBPM studies with depressed BD subjects will further enable progress towards paradigms that capture all of the mood cycles defining this disorder. Assessment of the relationship between hBPM activity and performance on neuropsychological measures such as the IGT and WCST will also help to refine the validity and interpretation of behavior in the exploratory paradigm.

The primary limitation of the current study is the small sample size for subgroups examined within the BD cohort (e.g., n = 10–15 for outpatients on or off mood stabilizer medication). Given the number of factors that may impact inhibitory deficits and interact with medication effects, such as illness duration, additional studies with larger cohorts that examine the effects of specific treatment regimens (e.g., valproate vs. lithium) would provide valuable information about the utility of the hBPM to evaluate novel therapeutics for BD.

In conclusion, we report that euthymic BD outpatients exhibit inhibitory deficits in the hBPM compared to HC participants, including greater interaction and perseveration with novel objects. Our data support a growing body of evidence indicating that disinhibition is a core feature of BD that manifests across all phases of the disorder. Establishing objective and reliable methods to quantify and treat BD inhibitory deficits represents a critical health issue, since this phenomenon may be associated with the propensity to engage in self-destructive activities including risky sexual behavior, reckless driving, theft, and increased suicidal ideation (Lombardo et al., 2012; Swann et al., 2011; Swann et al., 2009). Our findings signify that the hBPM can serve as an effective tool to evaluate both trait- and state-based BD effects on inhibitory behavior and assess the therapeutic utility of treatments for this illness.

References

- Akiskal HS, Benazzi F. Toward a clinical delineation of dysphoric hypomania - operational and conceptual dilemmas. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7:456–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler LL, Ventura J, van Gorp WG, Green MF, Theberge DC, Mintz J. Neurocognitive function in clinically stable men with bipolar I disorder or schizophrenia and normal control subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Barkay G, Dzemidzic M, Albrecht D, Karne H, Zheng QH, Hutchins GD, Normandin MD, Yoder KK. Striatal dopamine transporter availability in unmedicated bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2011;13:406–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Ng F, Wang WV, Calabrese JR, Mitchell PB, Malhi GS, Tohen1 M. The empirical redefinition of the psychometric criteria for remission in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;106:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;113:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann JB, van de Laar YM, Neeleman MP, Stam HJ. Ambulatory accelerometry to quantify motor behaviour in patients after failed back surgery: a validation study. Pain. 1998;74:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa KN, Baker RW, Shao L, Yatham LN, Tohen M, Gershon S, Kupfer DJ. Rates of response, euthymia and remission in two placebo-controlled olanzapine trials for bipolar mania. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5:1–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbert PM, White JD, Grothe KB, O'Jile J, Kirchner KA. Physical activity in patients who are severely mentally ill: feasibility of assessment for clinical and research applications. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2006;20:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. (3rd ed.) Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Russo PV, Masten VL. Multivariate assessment of locomotor behavior: pharmacological and behavioral analyses. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1986;25:277–288. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani DG, Lee B, Robertson CL, Tabibnia G, Morgan AT, De Shetler N, Brown AK, Monterosso JR, Aron AR, Mandelkern MA, Poldrack RA, London ED. Striatal dopamine D(2)/D(3) receptors mediate response inhibition and related activity in frontostriatal neural circuitry in humans. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:7316–7324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4284-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford UP; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J, Hilbe J. Generalized Estimating Equations. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henry BL, Minassian A, van Rhenen M, Young JW, Geyer MA, Perry W. Effect of methamphetamine dependence on inhibitory deficits in a novel human open-field paradigm. Psychopharmacology. 2011;215:697–707. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry BL, Minassian A, Young JW, Paulus MP, Geyer MA, Perry W. Cross-species assessments of motor and exploratory behavior related to bipolar disorder. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo . Equivital lifemonitor. Cambridgeshire, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe J. Negative Binomial Regression. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Calltharp S, Rosenbaum ED, Faraone SV, Rosenbaum JF. Behavioral inhibition and disinhibition as hypothesized precursors to psychopathology: implications for pediatric bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:985–999. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Cayton GA, Rosenbaum JF. Laboratory-observed behavioral disinhibition in the young offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a high-risk pilot study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:265–271. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AD, Brooks DJ, Whone AL. Ventral striatal dopamine synthesis capacity predicts financial extravagance in Parkinson's disease. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:90. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo LE, Bearden CE, Barrett J, Brumbaugh MS, Pittman B, Frangou S, Glahn DC. Trait impulsivity as an endophenotype for bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2012;14:565–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Colom F, Torrent C, Sanchez-Moreno J, Reinares M, Benabarre A, Goikolea JM, Brugue E, Daban C, Salamero M. Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients: implications for clinical and functional outcome. Bipolar Disorders. 2004a;6:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Reinares M, Colom F, Torrent C, Sanchez-Moreno J, Benabarre A, Goikolea JM, Comes M, Salamero M. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004b;161:262–270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian A, Henry BL, Geyer MA, Paulus MP, Young JW, Perry W. The quantitative assessment of motor activity in mania and schizophrenia. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;120:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian A, Henry BL, Young JW, Masten V, Geyer MA, Perry W. Repeated assessment of exploration and novelty seeking in the human behavioral pattern monitor in bipolar disorder patients and healthy individuals. PloS one. 2011;6:e24185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opler MG, Yang LH, Caleo S, Alberti P. Statistical validation of the criteria for symptom remission in schizophrenia: preliminary findings. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Geyer MA. A scaling approach to find order parameters quantifying the effects of dopaminergic agents on unconditioned motor activity in rats. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 1991;15:903–919. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(91)90018-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry W, Minassian A, Henry B, Kincaid M, Young JW, Geyer MA. Quantifying over-activity in bipolar and schizophrenia patients in a human open field paradigm. Psychiatry Research. 2010;178:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry W, Minassian A, Paulus MP, Young JW, Kincaid MJ, Ferguson EJ, Henry BL, Zhuang X, Masten VL, Sharp RF, Geyer MA. A reverse-translational study of dysfunctional exploration in psychiatric disorders: from mice to men. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1072–1080. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Courchesne E. Evidence for a cerebellar role in reduced exploration and stereotyped behavior in autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:655–664. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot J, Whitton A, Parker G, Doran J, Manicavasagar V, Delmas K. Triggers of mania and depression in young adults with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;143:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa AR, Reinares M, Michalak EE, Bonnin CM, Sole B, Franco C, Comes M, Torrent C, Kapczinski F, Vieta E. Functional impairment and disability across mood states in bipolar disorder. Value Health. 2010;13:984–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KA, Vederman AC, McFadden EM, Weldon AL, Kamali M, Langenecker SA, McInnis MG. Differential executive functioning performance by phase of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2012;14:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims J, Smith F, Duffy A, Hilton S. The vagaries of self-reports of physical activity: a problem revisited and addressed in a study of exercise promotion in the over 65s in general practice. Family Practice. 1999;16:152–157. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D. Pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar mania: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:551–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Kjome KL, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Criminal conviction, impulsivity, and course of illness in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2011;13:173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Severity of bipolar disorder is associated with impairment of response inhibition. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;116:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Pazzaglia P, Nicholls A, Dougherty DM, Moeller FG. Impulsivity and phase of illness in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;73:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres IJ, DeFreitas CM, DeFreitas VG, Bond DJ, Kunz M, Honer WG, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Relationship between cognitive functioning and 6-month clinical and functional outcome in patients with first manic episode bipolar I disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2010a;41:971–982. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres IJ, DeFreitas VG, DeFreitas CM, Kauer-Sant'Anna M, Bond DJ, Honer WG, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Neurocognitive functioning in patients with bipolar I disorder recently recovered from a first manic episode. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010b;71:1234–1242. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04997yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Enkhuizen J, Geyer MA, Kooistra K, Young JW. Chronic valproate attenuates some, but not all, facets of mania-like behaviour in mice. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology / Official Scientific Journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum (CINP) 2012:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivometrics . The LifeShirt System™. Ventura, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Michelhaugh SK, Bannon MJ. Valproate robustly increases Sp transcription factor-mediated expression of the dopamine transporter gene within dopamine cells. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25:1982–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, Goey AK, Minassian A, Perry W, Paulus MP, Geyer MA. The mania-like exploratory profile in genetic dopamine transporter mouse models is diminished in a familiar environment and reinstated by subthreshold psychostimulant administration. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2010;96:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, Henry BL, Geyer MA. Predictive animal models of mania: hits, misses and future directions. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011a;164:1263–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, Minassian A, Paulus MP, Geyer MA, Perry W. A reverse-translational approach to bipolar disorder: rodent and human studies in the Behavioral Pattern Monitor. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2007;31:882–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, van Enkhuizen J, Winstanley CA, Geyer MA. Increased risk-taking behavior in dopamine transporter knockdown mice: further support for a mouse model of mania. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2011b;25:934–943. doi: 10.1177/0269881111400646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Huguelet P, O'Neil RL, Giordani BJ. Cognitive function in euthymic bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2001;102:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]