Huntington disease HD impacts the quality of life of both affected individuals and their individual family members. In particular, teens growing up in HD families report atypical, complex, and, at times, painful experiences, as well as increased caregiving responsibilities (Driessnack et al., 2011; Duncan et al., 2007; Keenan et al., 2007; Sparbel et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2009). As part of a larger study examining the impact of HD on families, we explored the specific concerns of these teens, and the strategies they used to address their concerns. The teens’ concerns informed the development of the Huntington Disease Teen Inventory (HD-TI), which has been previously reported (Driessnack et al., 2011). In this paper, we focus on the strategies teens reported using, as well as the helpfulness of those strategies.

HD is a neurodegenerative genetic condition associated with the inheritance of a mutation in the HTT, or huntingtin gene on chromosome 4 (Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group, 1993). HD follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, which means that teens who have a parent with HD have a 50-50 chance of inheriting the mutated HTT gene. HD primarily involves a triad of clinical symptoms: (1) involuntary movement (chorea); (2) progressive cognitive dysfunction; and (3) psychiatric or behavioral disturbances, such as depression, irritability, and impulsivity (Sturrock & Leavitt, 2010). The mean age at onset of these clinical symptoms is 35 to 44 years and the median survival time is 15 to 18 years after the first appearance of motor symptoms (Sturrock & Leavitt, 2010). More recently, a prodromal period has been recognized, during which cognitive changes, such as difficulty with memory, attention, and executive function, may be shown to be present up to 15 years prior to motor diagnosis (Paulsen, 2010). The timeline for presentation of HD clinical symptoms means that teens in these families are often coming of age when HD is unfolding in their parent (Vamos, 2007; Driessnack et al., 2011; Sparbel et al., 2008). In some families, it may be the grandparent who has HD symptoms, and in the case that the parent also has the gene mutation, the teen’s parent may be either in the prodromal phase or not yet showing any HD symptoms. In these situations, the teens and their parents are both ’watching and waiting in the shadow’ of this disease (Sparbel et al., 2008).

Three additional forces add to the impact on teens living in a HD family. First, because of the autosomal dominant inheritance and timing of clinical symptoms teens are coming to terms with HD presenting in their parent as, they simultaneously find ways to cope with their own genetic risk and possible future (Keenan et al., 2007). Second, teens who are at risk for developing HD are not eligible for predictive genetic testing until they reach 18 years of age. As a result, teens often ‘hold their breath’ and avoid making future plans (Duncan et al., 2007). When asked about their most salient concerns, teens and young adults indicated that worry about whether or not they would develop HD, and making the decision to have HD genetic testing were two of the most common concerns (Driessnack et al., 2012). Third, HD is often not talked about as many families conceal the existence of HD and the stresses of managing it, not only within their communities, but also within their families (Quaid et al., 2008).

The purpose of this report is to identify use and helpfulness of strategies by teens growing up in HD families. Data were sought purposely from both teens and from young adults who were asked to recall their teen experiences, in order to capture the experience of teens, as well as those experiences that continued to be easily recalled into young adulthood.

Method

This study used an exploratory descriptive design that employed individual surveys. We conducted a onetime, nationwide mailed paper and pencil survey (Groves et al., 2009). A survey of minor age teens and young adults recalling their experiences as teens provides the opportunity to measure frequencies and helpfulness of strategies used during one’s adolescence with a parent, aunt or uncle, or grandparent with HD.

Sample and Data Collection

Those eligible for the study were teens, ages 14–17, and young adults ages 18–30, with a parent, aunt/uncle, or grandparent with HD. Following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, the study was announced through a HD Registry, a HD Center of Excellence newsletter, and at the annual meeting of the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (HDSA). Recruitment efforts extended from 2006–2008, and have been described in more detail previously (Driessnack et al., 2012). A letter containing elements of informed consent and the survey were mailed to families of people with HD in the HD Registry who had a teen or young adult. All those receiving the mailing had previously provided their addresses when they joined the Registry. A second wave of recruitment occurred in 2008 at the annual Huntington Disease of Society of America National Convention where the study materials were available at a table at the HDSA convention. Young adults indicated their consent by returning the survey. Parents of teen participants provided written permission, and teens indicated their assent by returning the survey. Surveys were returned through U.S. mail in self-addressed stamped envelopes that were provided to participants with the survey. Upon completion, participants received their choice of either a phone card or an iTunes gift card worth $25.00.

Measurement

HD Family Survey- Teen Survey

All participants completed the HD Family -Teen Survey, which contained basic demographics, and 75 coping strategy items. The demographics section contained 12 questions regarding the teen, and 14 questions regarding his/her relative with HD. The measure was a component of a larger study in which the HD Family-Teen Survey strategy items were developed from six focus groups with 32 teens in the USA and Canada (Sparbel, et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2009). Content was validated with experts in HD, clinical care or research with people with HD and their families, and teens from the original focus groups (Driessnack et al., 2012). Each item was responded to using a scaled response (0–3) (Table 1). Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for the overall scale was 0.92 (95% CI 0.88–0.95). Each of the 75 items was responded to twice. The first response, labeled as “use”, was scored as 0 if the strategy was not used and 1 if the strategy was used. The second response, labeled as “ helpfulness”, was a scaled rating of 1 (for not helpful) to 3 (for very helpful) and contingent, as this second score appeared only for respondents who indicated they had used the strategy. In addition, participants were provided with an opportunity to identify any strategy they used that was not on the survey. NA (not applicable) was offered as an option, as some items might not apply to a specific family’s situation, such as questions referring to a family member in a nursing home. No problems with this section were identified by teens who provided a review of the content and format of the survey.

Table 1.

Directions to participants: Please indicate how you manage your concerns. For example, when you read the statement, “I protect him/her from being injured by him/her” and you do NOT do this, circle “0”. If you try this, and it is somewhat helpful, circle “2”. If the statement doesn’t apply to you, circle “4”

HD Family Survey- Teen Questionnaire Strategies Sample Items

| How Helpful or Not Helpful it is:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I don’t do this | Do this, but it is not helpful | Do this and it is somewhat helpful | Do this and it is very helpful | Not applicable | |

| I talk to friends | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I gather information from family | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I make an effort to spend quality time with him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I keep busy with activities outside school and/or work | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I hold in my emotions | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I spend time with my friends | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Data Analysis

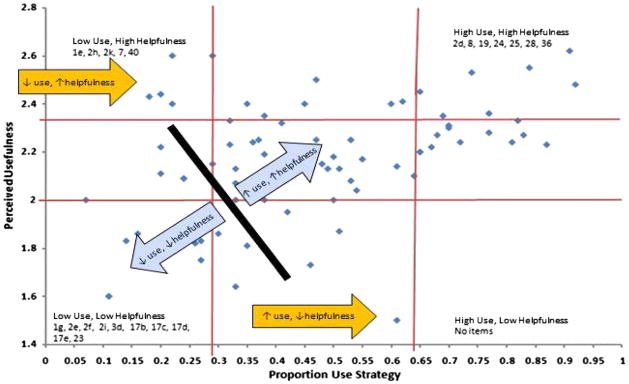

For each strategy item, the proportion of use and the mean helpfulness were computed. Correlation of proportion of use and mean helpfulness was determined. The relationship of use and helpfulness was categorized as being in the highest and lowest quartile on each dimension, creating four distinct categories: Low use and helpfulness, Low use and High helpfulness, High use and Low helpfulness, or High use and helpfulness (Table 2).

Table 2.

Strategies in Use and Helpfulness Quartiles

Low Use, High Helpfulness

|

Low Use, Low Helpfulness

|

High Use, High Helpfulness

|

Higher Use, Low Helpfulness

|

Results

Sample

Twenty-three teens and 21 young adults participated (N=44). Respondents lived in 19 different US states, 68% of the sample was female, and 92% was White (Driessnack et al., 2012). We could not calculate overall response rate due to our recruitment procedures.

HD Family- Teen Survey

The mean proportion of strategy usage was 0.46 and the mean helpfulness was 2.16 (on a 1–3 scale, with an overall correlation between proportion of use and helpfulness of +0.49 (95% CI = 0.23 to 0.61, p < 0.01). There was a statistically significant difference between males on females in ratings of helpfulness on six of the 75 items, with females’ ratings being significantly higher than males on each item (Table 3). In addition, responses on 5 items were reported as being more helpful by young adults recalling strategies used as teens (Table 4). Ratings of use and helpfulness of strategies when the relative was a grandparent (13%) or aunt/uncle (6%) were not analyzed separately.

Table 3.

Teen Strategy Ratings of Somewhat or Very Helpful by Gender

| Male (n=14) | Female (n=30) | p (Chi Sq) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I talk to others in similar situation | 1/14 | 12/30 | 0.003 |

| I talk to counselor or therapist | 0/14 | 8/30 | 0.038 |

| I gather information about my concerns about my family member with HD from doing reports or research | 5/14 | 17/30 | 0.042 |

| I gather information about my concerns about my family member with HD from the HD Center staff | 0/14 | 13/30 | 0.001 |

| I gather information about my concerns about my family member with HD from conferences | 2/14 | 7/30 | 0.007 |

| I enjoy my relationship with him/her | 7/14 | 22/30 | 0.043 |

Table 4.

Teen Strategy Ratings of Somewhat or Very Helpful by Age Group Providing Response

| 14–17 (n=23) | 18–29 (n=21) | p (Chi Sq) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I help him/her getting dressed/undressed | 8/23 | 16/21 | 0.048 |

| I protect him/her from being injured | 7/23 | 21/21 | 0.010 |

| I use humor to cope | 7/23 | 19/21 | 0.018 |

| I frequently clean our house | 6/23 | 19/21 | 0.035 |

| I spend time with friends | 0/23 | 17/21 | 0.015 |

The scatterplot (Figure 1) suggested two sub-groups of response items: 1) those with a strong positive correlation (r = +0 .84) between use and perceived helpfulness, and 2) those with a negative or inverse relationship between use and perceived helpfulness. The cutoffs for the low and high quartiles on the use variable were 0.290 and 0.645 respectively and the cutoffs for the low and high quartiles on the helpfulness variable were 2 .00 and 2.33 respectively.

Figure 1.

Teen use strategy by perceived helpfulness.

Positively correlated sub-group

The positively correlated group of strategies (n = 69) demonstrated a strong correlation (r = 0 .84) between amount of use and perceived helpfulness. Because of the large numbers of strategies in this group, the strategies were further sub-divided into two categories and analyzed using conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The first subdivision was the “Low use/Low helpfulness” category (17 items), which included the use of medication, alcohol/tobacco/drugs, and a counselor. The second sub-division was the “High use/High helpfulness” (52 items), which included obtaining information about HD, actions on behalf of the parent with HD, and thinking about or doing something else (one form of coping by using distraction).

Negatively or inversely correlated sub-group

This group of strategies (n = 6) demonstrated negative or inverse relationships between amount of use and perceived helpfulness. The group was further sub-divided into two categories: 1) Low use, High helpfulness (5 items), and 2) Higher use, Low helpfulness (1 item). The “Low use, High helpfulness” strategies were for obtaining information and actions on behalf of the family member with HD. The single strategy with Higher use, but Low helpfulness was, “I hold my emotions in”.

Twenty-eight (64%) of the participants answered the open-ended item at the end of the survey, “Please indicate what else do you need to manage your concerns about the person with HD and yourself”. The most common responses were 1) a desire for more information about HD, and 2) a desire for the support of others who would understand. For example, one participant shared, “I needed somebody who understood HD and who understood me….I needed a chance and a choice to be only me… I still need that.”

Discussion

The teens reported using many well known helpful coping strategies. However two use patterns distinguished this group of teens. These patterns, which included strategies that were identified as: 1) helpful, but not being used and 2) not helpful, but being used anyway, may provide insight for nurses and other health care providers involved in these teens’ care.

The helpful but underused strategies included participating in HD Support Groups and attending HD Conferences, where support groups with teens led by a health care professional with expertise with this age group are often available. This is an important message and incentive for parents and providers to seek out and encourage teens’ participation in these events. Other strategies in this use pattern focused on limiting alcohol intake/abuse, and increasing home visits for the HD family member receiving nursing home care. These strategies also provide important insight for providers as potential high-impact supports for teens.

For teens the high use but not helpful strategy was “I hold my emotions in”. For some teens, it was the only or best strategy they had available to them. Respondents may also not show emotions so not to disrupt family harmony when a parent or family member has emotional irregularity. In these cases the teen might find it easier to comply with the person’s mood than to express their own feelings.

The recent development of social networking websites, i.e. Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, blogs about HD, and other online HD resources may provide a welcome outlet for these teens’ emotions and offer the possibility for obtaining information about HD. Social connectedness has been positively associated with adjustment, as well as less adverse caregiving experiences and isolation in teens with parents who have mental illness (Fraser & Pakenham, 2009). However, quality and safety concerns exist with social networking sites (Weitzman, Cole, Kaci, & Mandl, 2011). Risks include harm associated with the loss of privacy, if privacy risks are poorly understood or discounted. Self misrepresentation by website users may expose teens to risk; users of these sites may also receive inaccurate information, as social network sites vary in the extent to which HD information is mediated or monitored by experts. Social network sites may not adequately fulfill informational needs or address counseling concerns for teens who need assistance in developing healthy strategies to deal with their emotions.

The gender differences noted in strategy choices are consistent with reports regarding gender and coping strategies in which female adolescents are found to report greater use of coping strategies than males (Wilson et al., 2005). Females in this study were more likely to seek out information and to endorse the importance of the relationship they shared with the family member with HD. Although females may be more likely to use emotion-focused coping rather than problem-focused coping (Tamres et al. 2002), the strategies endorsed by females in this study may provide both emotional benefits as well as information to solve problems. Furthermore, strategy choices may be influenced by multiple factors aside from gender.

The overarching secrecy surrounding HD can contribute to the teen’s inability to be seen and heard. Nurses may encounter barriers in reaching out to these youth, as some families or youth are reluctant to become involved with health professionals for fear of intrusion by social services, and some youth may not identify themselves as in need of help (Keenan et al., 2007). However, nurses in the schools or community health care settings are in an ideal position to help these teens develop helpful strategies identified in this study to manage multiple challenges from HD. One resource that nurses can recommend is the Huntington Disease Society of America (HDSA) National Youth Alliance which provides informational material, video clips from teens in HD families, and social networking opportunities, (http://www.hdsa.org/nationalyouthalliance/nya-1/index.html). Another group, the Huntington’s Disease Youth Organization (HDYO), provides a website with a wealth of reliable HD information written by youth, for youth, and focused on providing support for teens and other youth (http://en.hdyo.org/).

As research and clinical practice enter the era of personalized medicine and its accompanying advances in genetic/genomic technology and testing, there is an even greater need to understand these experiences and develop/refine interventions to assist families as they learn about, and learn to live with, their genetic risk . Findings from this study raise questions regarding similarities and differences in experiences of teens and young adults in HD families in other countries, especially those with nationalized health care systems or with specific youth programs such as the Youth Carers Project in the UK (Keenan et al., 2007). The influence of additional factors, such as the type and use of social media on strategies that these individuals find useful, or the influence of family or community support, has not been examined. Finally, links between strategies and outcomes of these strategies on health of the teens, their family member with HD, and their families have not been reported. Many of the reports on teens in HD families have focused on issues surrounding genetic testing, or used qualitative methods to better understand teens’ experiences. Using surveys such as the HD Teen Inventory (Driessnack et al., 2012) and the HD Family Survey- Teen Questionnaire with these populations can increase understanding of specific needs that clinicians and national organizations may address.

The study was potentially limited by the small sample size and the potential for biased recall, as participants not only included teens, but also asked young adults to recall their experiences as teens. While our inclusion of young adults was purposive, emerging maturational tasks, continued challenges of living in a HD family, and the possibility of already knowing their genetic status, may have influenced the recall of their teen experience.

Nurses, among the most trusted professionals, are perfectly positioned to assist these teens and their families. While we are unable to change these teens’ at-risk genetic status, family situation, or the overarching secrecy surrounding HD, nurses are now able to assess their concerns and advise teens how to access and employ useful management strategies. In particular, nurses can query for different types of strategies and assist teens toward those that are most helpful. Some teens may require additional support through mental health counseling so they can develop constructive strategies to manage their multiple concerns about themselves, their family member with HD, and their families.

Acknowledgments

This was supported by an NIH/NINR grant (R01NR07079) to Janet K. Williams and linked with the NIH/NINDS grant (R01 40068), NIMH grant (R0101579), the Roy J. Carver Trust Medicine Research Initiative, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and a CHDI grant to Jane S. Paulsen. A portion of this report was presented at the 2010 International Society of Nurses in Genetics meeting. We thank the study participants and the National Research Roster for Huntington Disease patients and families.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Janet K. Williams, Chair of Behavioral and Social Science Research IRB-02, Professor of Nursing, The University of Iowa, 50 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242.

Martha Driessnack, 50 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242, Assistant Professor, The University of Iowa.

J. Jackson Barnette, Professor, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045.

Kathleen J.H. Sparbel, Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1515 5th Ave., Suite 400, Moline, IL 61265.

Anne Leserman, Huntington’s Disease Society of America, Mid Atlantic Regional Social Worker, 505 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10018.

Sean Thompson, Public Relations Coordinator, The University of Iowa, Department of Psychiatry, 200 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242.

Jane S. Paulsen, Professor of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neurology, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242.

References

- Downing NR, Williams JK, Leserman AL, Paulsen JS. Couples’ coping in prodromal Huntington disease: A methods study. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2012;21:662–670. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9480-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessnack M, Williams JK, Barnette JJ, Sparbel KJ, Paulsen JS. Development of the HD-Teen Inventory (HD-TI) Clinical Nursing Research. 2012;21(2):213–223. doi: 10.1177/1054773811409397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J, Williamson J, Rogers JG, Delatycki M. “Holding your breath”: Interviews with young people who have undergone predictive genetic testing for Huntington disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2007;143A:1984–1989. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin C, Juhl AR, Williams JK, Menglng M, Mills JA, Paulsen JS and the Investigators of the Huntington Study Group. Perception, experience, and response to genetic discrimination in Huntington Disease: The International RESPOND-HD study. American Journal of Human Genetics Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2010;153B(5):1081–93. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser E, Pakenham KI. Resilience in children of parents with mental illness: Relations between mental health literacy, social connectedness and coping, and both adjustment and caregiving. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2009;14:573–584. doi: 10.1080/13548500903193820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourarangeau R. Survey Methodology. 2. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan KF, Miedaybrodzka Z, van Teigjlingen E, McKee L, Simpson SA. Young people’s experiences of growing up in a family affected by Huntington disease. Clinical Genetics. 2007;71:120–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan KF, van Teijlingen E, McKee L, Midzybrodzka Z, Simpson SA. How young people find out about their family history of Huntington’s disease. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68 (10):1892–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman BM, Newman PR. Development through life: A psychosocial approach. Thomson Wadsworth; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen JS. Early detection of Huntington’s disease. Future Neurology. 2010;5:85–104. doi: 10.2217/fnl.09.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaid KA, Sims SL, Swenson MM, Harrison JM, Moskowitz C, Stepanov N, Westphal BJ. Living at risk: Concealing risk and preserving hope in Huntington disease. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2008;17:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparbel K, Driessnack M, Williams JK, Schutte DL, Tripp-Reimer T, McGonigal-Kenney M, Paulsen JS. The experiences of teens living in the shadow of Huntington Disease. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2008;17:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s10897-008-9151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock A, Leavitt BR. The clinical and genetic features of Huntington disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry & Neurology. 2010;23:243–259. doi: 10.1177/0891988710383573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LJ, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6(1):2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tarapata K and the HDSA Talking with Kids Workgroup. Talking with Kids: Huntington’s Disease Family Guide Series. Huntington Disease Society of America; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vamos M, Hambridge J, Edwards M, Conaghan J. The impact of Huntington’s disease on family life. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:400–404. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Cole E, Kaci L, Mandl KD. Social but safe? Quality and safety of diabetes related online social networks. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18:292–297. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Ayres L, Specht J, Sparbel K, Klimek ML. Caregiving by teens for family members with Huntington disease. Journal of Family Nursing. 2009;15:273–294. doi: 10.1177/1074840709337126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Barnette JJ, Reed D, Sousa VD, Schutte DL, McGonigal-Kenney M, Paulsen J. Development of the Huntington disease family concerns and strategies survey from focus group data. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2010;18:83–99. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.18.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Skirton H, Barnette JJ, Paulsen JS. Family carer personal concerns in Huntington disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68(1):137–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GS, Pritchard ME, Revalee B. Individual differences in adolescent health symptoms: The effects of gender and coping. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]