Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Mobile food vendors (also known as street food vendors) may be important sources of food, particularly in minority and low-income communities. Unfortunately, there are no good data sources on where, when, or what vendors sell. The lack of a published assessment method may contribute to the relative exclusion of mobile food vendors from existing food-environment research. A goal of this study was to develop, pilot, and troubleshoot a method to assess mobile food vendors.

STUDY DESIGN

Cross-sectional assessment of mobile food vendors through direct observations and brief interviews.

METHODS

Using printed maps, investigators canvassed all streets in Bronx County, NY (excluding highways but including entrance and exit ramps) in 2010, looking for mobile food vendors. For each vendor identified, researchers recorded a unique identifier, the vendor’s location, and direct observations. Investigators also recorded vendors answers to where, when, and what they sold.

RESULTS

Of 372 identified vendors, 38% did not answer brief-interview questions (19% were “in transit”, 15% refused; others were absent from their carts/trucks/stands or with customers). About 7% of vendors who ultimately answered questions were reluctant to engage with researchers. Some vendors expressed concerns about regulatory authority; only 34% of vendors had visible permits or licenses and many vendors had improvised illegitimate-appearing set-ups. The majority of vendors (75% of those responding) felt most comfortable speaking Spanish; 5% preferred other non-English languages. Nearly a third of vendors changed selling locations (streets, neighborhoods, boroughs) day-to-day or even within a given day. There was considerable variability in times (hours, days, months) in which vendors reported doing business; for 86% of vendors, weather was a deciding factor.

CONCLUSIONS

Mobile food vendors have a variable and fluid presence in an urban environment. Variability in hours and locations, having most comfort with languages other than English, and reluctance to interact with individuals gathering data are principal challenges to assessment. Strategies to address assessment challenges that emerged form this project may help make mobile-vendor assessments more routine in food-environment research.

Keywords: Mobile food vendors/ Street vendors/ Street foods/ Food carts, Food environment, Urban/ New York City/ Bronx, Immigrant workers, Measurement/ Assessment

INTRODUCTION

Mobile food vendors, also known as street food venders (e.g., carts, trucks, and roadside stands selling food), may contribute meaningfully to food environments in both urban and rural settings, and may be particularly important food sources in minority and low-income communities.1-4 Unfortunately, possibly due to the logistical challenges of assessing “moving targets”, mobile food vendors have generally been neglected in food-environment research.

Only a few published studies have attempted to assess any aspects of mobile food vending, and have generally done so with limited scope on a limited scale. In developing countries, studies have typically used indirect measures in very select samples, often with a focus on food safety.5-8 There has also been food-safety-related mobile-vendor work in the U.S. (e.g., a 10-cart study in Manhattan).9 Other work in the U.S. has had more of a nutritional focus, but has been limited in assessing mobile food vendors indirectly (e.g., through customer surveys, evaluating reported purchasing and consumption practices).3,10,11 Direct assessment of mobile food vendors with a nutritional focus in the U.S. has largely been restricted to observed transactions with customers (e.g., on the streets around six4 or fewer12 urban schools) or surveys with vendors (e.g., a sample of 13 vendors in a sample of rural colonies2).

No published studies to date demonstrate a method for conducting a detailed assessment of mobile food vendors for a sample of more than just a few carts. Also, there are no adequate government or private sources for these data, precluding secondary analyses. Still, ignoring mobile food vendors could give an incomplete and inaccurate picture of an overall food environment, leading to erroneous conclusions and misdirected interventions to change food environments.

For the current study, investigators sought to develop a method for assessing mobile food vendors, and to pilot the assessment methodology in an urban setting: Bronx County, NY (the Bronx). The developed method built on important earlier work by others,2-7,9-12 and on related work by members of the research team.13 The findings presented in this manuscript detail methods, challenges, and lessons learned. They suggest strategies for others to overcome obstacles and conduct detailed assessments of mobile vendors in future food-environment research.

METHODS

Study design and overview

The Albert Einstein College of Medicine institutional review board approved the study protocol, to conduct a cross-sectional assessment of mobile food vendors in the Bronx using a mixed-methods approach. The method involved canvassing Bronx streets to determine vendor locations, making direct observations of vending vehicles (e.g., carts, trucks, stands), and conducting brief interviews with vendors to determine where, when, and what they sold. Notably, the unit of analysis for this study was the vending vehicle (i.e., the cart, truck, or stand) not the vendor (i.e., the person). Thus, the risks involved for “human subjects” in this assessment were low. Investigators who collected data were all college and pre-professional students; prior work related to food-environment assessments suggests student investigators may encounter fewer barriers to data collection due to their young age and their student status14 (e.g., less likely to be mistaken for government officials or regulatory authority and more likely to be well-received b vendors).

Developing an assessment tool

The principal investigator (lead author) designed a draft assessment tool based on two days of observing mobile food vendors in familiar Bronx neighborhoods. The tool was meant to capture essential elements of a ‘mobile’ food environment, as distinct from the ‘static’ food environment of restaurants, markets, and other store-front retail. The principal investigator trained a pair of student investigators (who worked in the summer 2010) in use of the draft assessment tool during a one-hour session. Students then practiced assessing several vendors out on the street and based on this experience suggested modifications to the tool. With the revised tool, students and the principal investigator separately conducted subsequent assessments of several more vendors. Agreement was essentially perfect (actual tool available from authors upon request; details of tool below).

A second pair of students (who worked in fall) likewise received a one-hour training from the principle investigator and then conducted practice assessments of several vendors. These students received feedback on their performance and achieved proficiency with assessment after a second practice session (i.e., student assessments agreed with separate assessments done by the principal investigator as a reliability check).

Canvassing streets

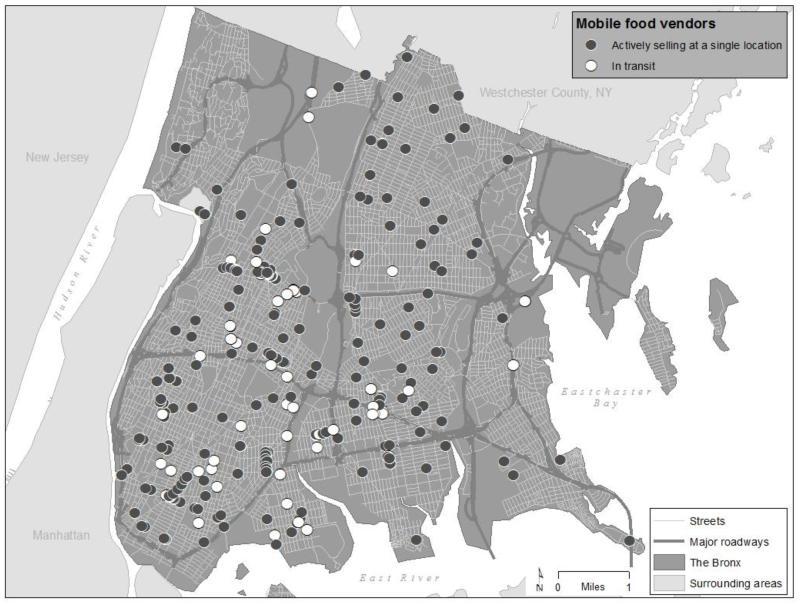

Assessments encompassed all publicly accessible roads in the Bronx (approximately 1,000 linear miles over 42 square miles, Figure 1), including highway entrance and exit ramps, but excluded major highways and private roads. Investigators used printed Google maps to plan and record their routes. Assessments occurred during business hours on non-consecutive weekdays, summer through fall in 2010. Two pairs of investigators—one working in the summer, the other in the fall —canvassed Bronx streets. One investigator in each pair drove a private vehicle; the other investigator scanned both sides of each street en route for mobile food vendors. When a vendor was identified, investigators marked the printed map with the location and approached the vendor. Investigators did not approach vendors “in transit” (e.g., ice cream trucks driving through neighborhoods) but recorded where such vendors were when spotted, along with as much information as they could about the vendors based on direct observation.

Figure 1. Map of Bronx streets and the location of mobile food vendors.

Of the vendors “in transit” (N = 72), the vast majority were ice-cream trucks and other frozen-novelty vendors (N = 51). These venders generally do not sell in one place, but rather drive through neighborhoods trying to attract customers, intermittently stopping to make sales and then continuing on. Water vendors (N = 11) also do not generally stay in one place but rather often walk up to motorists and pedestrians with bottled water. Other vendors identified “in transit” were not actively selling when identified and included vendors of various prepared foods (N = 5), produce (N = 4), and nuts (N = 1).

Note: The map above may appear to show fewer than 372 points due to substantial overlap in areas with a high density of mobile food vendors. Investigators focused assessment on the mainland Bronx, not the islands that are also technically part of the borough although not connected to the mainland by roads. The exception was City Island (the island most proximal to the borough’s eastern border), which is connected to the mainland by a road and which investigators did assess.

Direct observation

Items from the assessment tool included direct observations like unique identifier (e.g., permit number, license plate, or unique physical characteristics like stickers, signage, damage, or graffiti) and location (i.e., nearest street address or nearest street intersection). Investigators noted if vending vehicles were functionally mobile (i.e., able to move immediately as needed, like ice cream trucks) or functionally stationary (i.e., requiring preparation before moving like vendors selling produce from roadside tables where product had to be boxed up and loaded before moving). Investigators recorded if vendors operated inside vehicles (e.g., food trucks) or outside vehicles (e.g. push carts). Investigators also recorded if similar products might be available from store-front businesses visible from the vendor’s location (e.g., if there was an ice-cream store three doors down from an Italian-ice vendor, or if a diner was across the street from a lunch truck). Additionally, investigators recorded specific types and varieties of foods and beverages offered by each vendor (analyzed in a separate manuscript under review: Lucan et al, unpublished data). If there were interesting observations that were not part of the structured assessment tool, investigators recorded these qualitatively (e.g., “The vendor left his truck when he saw us approaching him: located at 4:36pm, ultimately interviewed at 4:50pm”).

Brief interviews

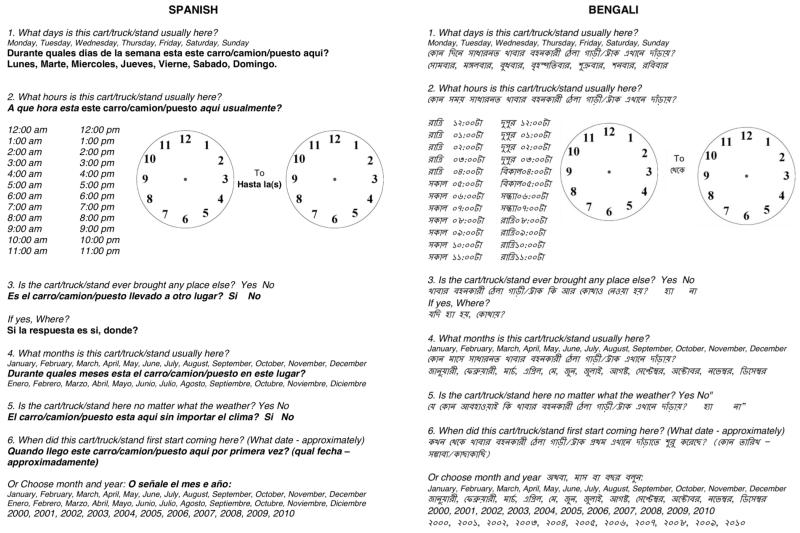

The assessment tool also included a few short closed-ended interview questions for vendors: how long the business had been operating, where and when the cart, truck, or stand usually sells (hours, days, months), and if weather is generally a factor for selling (Figure 2). Student investigators wore casual clothes and tried to engage vendors in informal conversation about their vending experience, weaving in the specific, structured, closed-ended interview questions where able.

Figure 2. Mobile food vendor interview guide, with translation into Spanish and Bengali.

Based on earlier work by members of the research team13 and communication with a Bronx street-vendor association, investigators assumed that most vendors would be Spanish-speaking and that a substantial number would speak Bengali. At least one student in each data-collection pair was bilingual in English and Spanish, and the study interview guide was translated into (and then back-translated from) Spanish and Bengali (Figure 2).

Interviewers only used the written interview guide when necessary (e.g. when vendors only spoke Bengali and had to select from pre-written answers). Otherwise, interviewers recorded oral answers on a separate form after the interview was complete. Interviewers also recorded specific observations on the form: the language vendors reported being most comfortable speaking, reasons for any difficulty with the interview (e.g., vendor refusal or perceived reluctance to participate) and qualitative jottings about any interesting information that emerged in conversations (e.g., “The vendor mentioned that the police continue to harass her even though she has a valid permit”).

Data analysis

Investigators analyzed direct observations and vendors’ answers to closed-ended interview questions within predefined quantitative and categorical domains. Stata 11 (Statacorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for data exploration and to calculate frequencies. ArcGIS software (version 9.3.1, ESRI, Redlands, CA) was used to map vendor locations. The research team discussed any qualitative jottings from observations and interviews to be sure there was interpretation consensus.15

RESULTS

Cumulatively, the two pairs of student investigators were able to complete assessment of all Bronx streets over 40 non-consecutive days (roughly 320 person-hours in the field). Data entry and data cleaning (e.g., regular checks for missing observations and out-of-range values) consumed about another 320 person-hours. Thus, total effort was about 0.64 person-hours for each linear mile of roadway covered, or about 15 person hours for each square mile of area covered.

The assessments identified 372 mobile food vendors—nearly nine per square mile on average (Figure 1). More details on types of vendors and the various foods and beverages they offered at different times in different neighborhoods are available elsewhere (Lucan et al, unpublished data, under review).

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics based on researchers” experience assessing mobile food vendors. Select qualitative observations appear in footnotes to the table and also below.

Table 1. Researchers’ experience assessing mobile food vendors on Bronx streets and factors potentially complicating future assessments.

| Assessment experience and potentially complicating factors | N (%)a |

|---|---|

| Assessment experience by interview status | 372 (100) |

| Vendor not Interviewed (answered no questions) | 141 (37.9) |

| Vendor actively in transit (e.g., ice-cream trucks en route) | 72 (51.1) |

| Vendor refusedb | 56 (39.7) |

| Vendor absent from cart, truck, or stand | 7 (5.0) |

| Vendor with long line of customers | 5 (3.6) |

| Language barrier | 1 (0.7) |

| Vendor interviewed (answered at least some questions) | 231 (62.1) |

| No difficulty; vendor cooperative and easily engaged | 197 (85.3) |

| Vendor seemed reluctant, nervous, suspiciousc | 17 (7.4) |

| Language barrier | 12 (5.2) |

| Vendor not owner; unsure how to answer interview questions | 4 (1.7) |

| Vendor with customers | 1 (0.4) |

| Factors potentially complicating future assessment | |

| Reporting time vending d | 213 (57.3) |

| Vendors starting business this year | 43 (20.2) |

| Median time vending: 4 years (range: <1 week to 35 years) | |

| Language vendor most comfortable speaking d | 225 (60.5) |

| Spanish | 173 (76.9) |

| English | 40 (17.8) |

| Bengali | 7 (3.1) |

| Arabic | 4 (1.8) |

| Albanian | 1 (0.4) |

| Reporting usual number of days selling d | 227 (61.0) |

| 7 days per week | 75 (33.0) |

| 6 days per week | 55 (24.2) |

| 5 days per week | 68 (30.0) |

| 4 days per week | 7 (3.0) |

| 3 days per week | 8 (3.5) |

| 2 days per week | 2 (0.9) |

| 1 day per week | 1 (0.4) |

| Inconsistent number of days per week | 11 (4.9) |

| Reporting usual pattern of days selling d | 227 (61.0) |

| Monday-Sunday | 75 (33.0) |

| Monday-Friday and one week-end day | 54 (23.8) |

| Monday-Friday and no week-end days | 67 (29.5) |

| Some days Monday-Friday but no week-end days | 13 (5.73) |

| Both week-end days and any day(s) Monday-Friday | 3 (1.3) |

| One week-end day and any day(s) Monday-Friday | 2 (0.9) |

| Inconsistent pattern of days selling | 13 (5.7) |

| Reporting usual vending hours d | 211 (56.7) |

| Median start hour: 10 am (range: 3 am - 4 pm) | |

| Median end hour: 6pm (range: noon - 10pm) | |

| Reporting usual vending months d | 203 (54.6) |

| Vendors selling year round (all 12 months) | 49 (24.1) |

| Median start month: April (range: January - September) | |

| Median end month: October (range: July - December) | |

| Reporting ever selling elsewhere d e | 227 (61.0) |

| Yes | 67 (29.5) |

| No | 160 (70.5) |

| Having the ability to move elsewhere easily f | 372 (100) |

| Yes | 262 (70.4) |

| No | 110 (29.6) |

| Vending from inside vending vehicle g | 372 (100) |

| Yes | 78 (21.0) |

| No | 294 (79.0) |

| Reporting vending irrespective of weather d | 216 (58.1) |

| Yes | 30 (13.9) |

| No | 186 (86.1) |

| Selling adjacent to store-front competitorsh, i | 300 (80.6) |

| Yes | 64 (21.3) |

| No | 236 (78.7) |

| Displaying mandatory vending permit and/or license h | 300 (100) |

| Yes | 102 (34.0) |

| No | 198 (66.0) |

Percentages within categories may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Reasons for refusing to answer questions included: concern that answering would “cause trouble” or adversely affect the vendor’s business; reportedly being “too busy” (even when no customers were in sight); reportedly having “no time”; reportedly having to leave (e.g., to make an appointment elsewhere); reportedly not being the owner and not authorized or informed enough to answer; getting advice from an customer, adjacent vendor, or friend to not communicate with investigators; or unstated

Vendors often repeatedly asked what interview questions were about and requested to see investigators’ identification (but were seldom reassured by student badges). Some vendors described harassment by adjacent store-front businesses (e.g. verbal threats and threatening notes left on vending vehicles); they worried about getting tickets from police, which reportedly was common. They also worried about health inspectors and being closed down. Even when participating in interviews, some vendors’ answers often tended to be vague and evasive.

Data available for <100% of total sample if: vendor “in transit”; not at cart, truck, or stand; with customers; unable or unwilling to answer specific question; or not speaking enough English or Spanish to understand inquiry and communicate a response to bilingual investigators.

Selling on other streets, in other neighborhoods, or even in other boroughs of the city

Some vendors could easily and rapidly change location as needed (e.g., trucks, vans, push carts) whereas others could not (e.g., those selling from stationary tables or stands that would have to be packed up before moving)

Whether the vendor was protected inside of the vehicle (e.g., food truck) or not (e.g. push cart) had implications for whether the vendor came out during inclement whether, and also often affected the interview dynamic (e.g., vendors having the ability to abruptly shut vending window and hide inside of the vehicle, claiming to be closed).

Data available for <100% of total sample because of vendors “in transit”

If similar products might be available from store-front businesses visible from the vendor’s location (e.g., if there was an ice-cream store three doors down from a snow-cone vendor).

Investigators were unable to conduct full interviews with 38% of identified vendors. In just over half of these cases, vendors were actively “in transit” (e.g., ice-cream trucks driving through neighborhoods trying to attract customers). In other cases, vendors were absent from their cart/truck/stand (some leaving when they saw investigators approaching) or were with customers. In 40% of cases where interviews did not occur, vendors outright refused to speak with student investigators. In other cases, even when there was no outright refusal to speak, vendors sometimes seemed suspicious, guarded, or reluctant to engage with investigators (e.g., taking actions like shutting the truck window when investigators introduced themselves, or packing up to leave as investigators approached). Informal discussions with vendors who did ultimately speak with students revealed that many perceived constant harassment by police and adjacent store-front businesses. More than 20% of vendors were, in fact, selling adjacent to likely store-front competitors and only a minority of vendors (34%) displayed the requisite vending permit or license, with many vendors having informal set-ups (e.g., Spanish foods being sold from a converted shopping cart). Perceived reluctance/nervousness about speaking with investigators (7% of all interviews) was inversely associated with having a visible permit or license (data not shown).

In a few cases, a language barrier prevented or impeded interviews. This did not occur often because vendors most often reported the greatest comfort speaking English or Spanish and members of both investigator pairs were fluent in both of these languages. For >85% of interviews that did occur, vendors were friendly, open, and generally happy to converse—presumably hoping to build their businesses and attract new customers (e.g., offering free water to investigators along with enthusiastic answers to when and where they sell).

A full third of vendors (33%) sold seven days a week; a majority (87%) sold at least five days, most with some week-end and week-day selling. An eight-hour workday from 10am - 6pm defined the median hours of operation, and April to October were the usual vending months. However, there was substantial variation in the hours, days, and months that vendors sold. Nearly 6% of vendors reported an inconsistent or variable pattern in days selling.

Almost a third of vendors (30%) reported selling in areas other than where investigators identified them. In fact, researchers occasionally saw the same carts/trucks/stands they had already assessed in different places at subsequent times. Greater than 70% of vendors had the kinds of set-ups that allowed for easy mobility should they decide to move (e.g., trucks, vans, and push carts as opposed to relatively-fixed tables, stands, or unattached trailers).

More than 20% of vendors had just started their businesses during the assessment year and were not fully confident of when or where they would sell in the future. Among all vendors, less than one quarter reported selling year-round.

Weather was a factor that added to variability to selling times. Seventy-nine percent of vendors had the kind of set-ups that left them exposed to the weather (e.g. open stands and push carts), which was associated with not vending in all weather (data not shown). In fact, for 86% of vendors, weather was a deciding factor in whether they would attempt to conduct business on a given day. Even those protected from the elements sometimes reported that bad weather (e.g., rain) reduced foot traffic and business, and made their coming out not worthwhile. Conversely, favorable weather could extend a planned vending season, with several vendors identified in the fall revealing that they did not usually sell this far into the year but decided to sell for longer given the unusually warm and fair conditions in the Bronx late into 2010.

Table 2 gives greater details on investigators’ experience with the assessment, listing assessment considerations, what worked, and what could have worked better in the field. The table provides strategies to inform the work of others and promote the assessment of mobile food vendors in future food-environment research.

Table 2. Lessons Learned: what worked, and what could have worked better for measuring mobile food vendors in an urban environment.

| Assessment consideration |

Experience in current study | Recommendations for future research based on successes in the current study |

Potential strategies to improve on the current study’s methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency in canvassing streets |

Investigators required 40 non-consecutive days (roughly 320 person-hours) to cover ~1,000 linear miles of variably-dense residential, commercial, and manufacturing zones by personal vehicle and by foot (including the time required to engage with 300 vendors and conduct 231 interviews). |

|

|

| Efficiency in data entry | Investigators spent about half of their time (roughly 320 person- hours) on data entry and data cleaning on the 40 non- consecutive days of data collection |

|

|

| Language preferences and proficiencies |

English was the language less than 20% of vendors reported being most comfortable speaking; more than three quarters of vendors were most comfortable speaking Spanish. |

|

|

| Identifying and distinguishing unique vending vehicles (carts, trucks, or stands) |

With two thirds of carts lacking permits or licenses, identification by permit or license number was only possible in a minority of cases. In some cases, different vendors operated the same cart, truck, or stand in different locations at different times. Often, umbrellas on carts did not match the business type (e.g., Halal food cart having a “Sabrett” hot-dog umbrella). |

|

|

| Timing of assessment during the day |

All assessments occurred during usual business hours on weekdays, which is when most vendors—even with other reported hours of operation— reported conducting most of their business. |

|

|

| Determining vendor location |

Investigators noted location on pre-printed maps and also recorded address data (i.e., closest address or street intersection). |

|

|

| Accounting for vendors actively “in transit” |

Almost 20% of all vendors were “in transit” at the time of identification. |

|

|

| Dealing with absentee vendors |

Nearly 2% of vendors were absent from their open carts, trucks, or stands. |

|

|

| Persons other than the owner vending |

In a number of cases, the person selling reported not being the owner, but rather a friend just watching the cart for a few hours or an employee who could not answer the study questions. |

|

|

| Consistency in vendor presence and location |

Vendors often changed location based on time (e.g., hour, day, month), and most reported not vending in certain weather (e.g., rain). Some vending vehicles were identified in different locations on different days. |

|

|

| Not disrupting vendor’s business |

In several instances vendors were with long lines of customers and not available for interview. |

|

|

| Investigator comfort/safety |

Both members of both teams of student investigators were unfamiliar with most Bronx neighborhoods. A female investigator occasionally felt uncomfortable in neighborhoods where male investigators felt less threatened. There were a few occasions on the street where police activity clearly signaled some immediate threat to personal safety. |

|

|

| Vendor reluctance to participate |

1 in 4 vendors that investigators approached either refused to participate or were reluctant to do so despite assurances that questions were only for a research study about community nutrition. There appeared to be concern about regulatory authority, with many vendors reporting getting expensive tickets from police and one vendor directly asking investigators if they were going to shut down her business and prevent her from selling food on the street anymore. A female investigator reported several instances where a vendor would not speak with her but would speak to male colleague. |

|

|

In some cases, vendors discussed selling for many years, with consistency on the street interrupted by prolonged trips back to countries of origin (e.g., Mexico, Dominican Republic, India, Bangladesh)

In some cases people on the street openly discouraged vendors from answering questions, warning that investigators could not be trusted and that talking to the research team would have negative repercussions

DISCUSSION

The pilot assessment in this study indicates that mobile food vendors are indeed “moving targets”, having inconsistent hours and locations that complicate assessment. Investigators’ assessment experience suggests strategies to overcome challenges, so that vendor assessment may be suitable for wider implementation in future food-environment research.

Among the most notable assessment challenges encountered were communication issues related to vendors’ reluctance to engage with investigators and, to a lesser degree, language preferences. Most vendors had low comfort with English, lacked official vending permits, and often vended from informal setups; all findings that had been reported previously from smaller-scale work in California.4 Such findings are not surprising given many vendors are likely recent immigrants,16 potentially lacking various skills and documentation necessary to obtain formal employment and therefore resorting to informal selling.2,17,18 Mobile food vending might be a particularly attractive option for new immigrants. More than 20% of vendors in the current study were new to vending in the past year, not dissimilar from the 46% reported in study of a rural setting.2

In that same rural setting, all mobile vendors reported holding a county vending permit2 whereas only a minority of vendors in the current study did. Permits may be an issue for future studies of mobile food vending in urban areas; vendor legitimacy in the current study correlated with vendors’ willingness to talk with investigators. Even permitted vendors might be hesitant to talk though; in the current study, even a few legitimate vendors reported harassment by police and adjacent store-front competitors and were wary of those asking questions because of it. Investigators conducting future work should be sensitive to this reality, and perhaps broach the subject in their introductions (e.g., “We want to assure you that we have no intention of harming your business in any way”). Additionally, other researchers have used promotoras (health workers from within the community), community residents, and even other vendors to broker interactions between investigators and mobile food vendors.2 Such facilitators may provide an effective way to establish rapport, remove barriers for interaction, reduce vendor uneasiness about questioning, and increase participation by vendors.

Another potential way to further increase vendor participation may be to have a good understanding of the times vendors are likely to work (e.g., hours, days, and months). Prior studies have provided few details in this regard. A rural study noted that 84.6% of vendors characterized their work as full time, with 100% working Saturday and 0% working Sunday.2 That study also noted that nearly 70% of mobile vendors did not sell in the fall and winter (a number roughly corresponding to the percentage of vendors exposed to the weather—e.g., selling from push carts or bicycles a opposed to covered vehicles).2 In comparison, at least 87% of the vendors in the current study worked five or more days per week, with several not working Saturday and more than a third regularly working Sunday. More than 75% of vendors did not sell year round (with a slightly greater percentage exposed to the elements and not selling in all weather). These data underscore that vendors have a variable presence based on day and season, and that weather conditions as well as the type of vending vehicle add additional variability to the times vendors are likely to be present.

The current study had several strengths. Investigators assessed mobile food vendors across a large urban area—all of Bronx county, NY—including greater than 25 times more vendors than any other U.S. studies to date.2,4,9,12 The research made strides towards developing a translatable mixed methodology for assessment, which included components of both direct observation and brief interviews for detailed and nuanced understanding. Investigators asked vendors about vending times, locations, and conditions under which they sell—potentially obviating an absolute need for multiple assessments at different times as attempted by others.4,5 Nonetheless, such repeat assessments may be essential if the purpose of the research is to provide a precise account of available foods in specific areas at specific times (e.g., the mobile vendors in neighborhoods around elementary schools near the time of school dismissal).4

The lack of repeat assessments is the current study’s biggest limitation: data came from a single cross-sectional assessment of a shifting target—an assessment that was conducted only on weekdays during business hours and that required several months to complete. Due to the size and scope of the project, investigators were not able to repeat assessments for reliability checking at other times, nor systematically confirm vendors’ reports of the other locations and times that they sold. An improvement on the methods would be to perform reliability checks in a sample of areas at different times and under different conditions (e.g., in different weather), having multiple teams in the field simultaneously to speed data acquisition and better approach simultaneity in observation. Another limitation of the current study is that many vendors did not participate in interviews with investigators, with a major reason being refusal. Since refusal was associated with whether or not vendors had a permit, it is likely that those who did not participate differed systematically from those who did. For instance, vendors who lacked permits and refused might have been more likely to stay on the move, deny speaking English (so as to have an excuse to not answer questions), and have more variable, less-consistent hours in a given location. To improve vendor participation in the future and to help address vendor reluctance to participate, several recommendations appear in Table 2 based on the experience in the current study. Finally, given various measurement issues as noted, it is possible that the current study’s assessment did not capture all mobile vendors in the Bronx. Unfortunately, there is no valid standard to gauge the completeness of the data. The city holds some records for vending permits, but these generally contain residential addresses only, not vending locations or hours and such records would be limited to only the roughly one third of all vendors on the street that may be licensed and legitimate. It is the lack of adequate pre-existing data on mobile food vendors that necessitates primary data-collection in the first place.

Conclusion

The experience of piloting a mobile-food-vendor assessment in the Bronx suggests it is possible to conduct such work over a sizeable area in an urban setting. Conducting such work is complicated by the fact that mobile vendors are literally moving targets; most have the capacity to move easily and a large majority do. Vendors report varying locations by day, date, time, and weather. Most vendors are not legitimate in terms of licensing, making attempts at assessment through government records futile. Illegitimacy makes primary assessment essential, but also challenges such assessment. Many vendors, feeling harassed by regulatory authority, are reluctant to speak to anyone who is not strictly a customer out of fear of jeopardizing their businesses. To engage with vendors, investigators should empathize with vendors’ concerns and be flexible in their approach, avoiding the use of official-looking paperwork and formal procedures when possible. While there may be greater logistical challenges to obtaining complete information on street vendors compared to more-static food sources like stores and restaurants, not to exert the effort neglects a likely important component of the overall food environment. The method presented here may serve as a starting point to encourage the consideration of mobile food vending more routinely in food-environment research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank A. Hal Strelnick, MD, for mentorship; Nandini Deb, MA, and Mahbooba Akhter Kabita for assistance with Bengali translation; Hope M. Spano and the Hispanic Center of Excellence at Albert Einstein College of Medicine for intern coordination and financial support for data collection; and Gustavo Hernandez for help with data collection.

FUNDING

This publication was made possible by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR025750, KL2 RR025749, and TL1 RR025748 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared; all authors deny any conflicts or competing interests of any kind.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The protocol was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Odoms-Young AM, Zenk S, Mason M. Measuring food availability and access in African-American communities: implications for intervention and policy. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Apr;36(4 Suppl):S145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valdez Z, Dean WR, Sharkey JR. Mobile and home-based vendors’ contributions to the retail food environment in rural South Texas Mexican-origin settlements. Appetite. 2012 Apr 21;59(2):212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Johnson CM. Use of Vendedores (Mobile Food Vendors), Pulgas (Flea Markets), and Vecinos o Amigos (Neighbors or Friends) as Alternative Sources of Food for Purchase among Mexican-Origin Households in Texas Border Colonias. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012 May;112(5):705–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tester JM, Yen IH, Laraia B. Mobile food vending and the after-school food environment. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Jan;38(1):70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mwangi AM, den Hartog AP, Mwadime RK, van Staveren WA, Foeken DW. Do street food vendors sell a sufficient variety of foods for a healthful diet? The case of Nairobi. Food Nutr Bull. 2002 Mar;23(1):48–56. doi: 10.1177/156482650202300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freese E, Romero-Abal ME, Solomons NW. The street food culture of Guatemala City: a case study from a downtown, urban park. Arch Latinoam Nutr. 1998 Jun;48(2):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahon BE, Sobel J, Townes JM, et al. Surveying vendors of street-vended food: a new methodology applied in two Guatemalan cities. Epidemiology and infection. 1999 Jun;122(3):409–416. doi: 10.1017/s095026889900240x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oguntona CR, Kanye O. Contribution of street foods to nutrient intakes by Nigerian adolescents. Nutr Health. 1995;10(2):165–171. doi: 10.1177/026010609501000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burt BM, Volel C, Finkel M. Safety of vendor-prepared foods: evaluation of 10 processing mobile food vendors in Manhattan. Public Health Rep. 2003 Sep-Oct;118(5):470–476. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahn M, Shavitz M. City Limits. Jan 9, 2012. Green Cart Vendors Face Diet of Challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abusabha R, Namjoshi D, Klein A. Increasing access and affordability of produce improves perceived consumption of vegetables in low-income seniors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 Oct;111(10):1549–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tester JM, Yen IH, Laraia B. Using mobile fruit vendors to increase access to fresh fruit and vegetables for schoolchildren. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012 May;9:E102. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucan SC, Maroko A, Shanker R, Jordan WB. Green Carts (Mobile Produce Vendors) in the Bronx-Optimally Positioned to Meet Neighborhood Fruit-and-Vegetable Needs? J Urban Health. 2011 Oct;88(5):977–981. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9593-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minkler M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr 1;100(Suppl 1):S81–87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, Calif.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales A, Kettles G. Healthy food outside: farmers’ markets, taco trucks, and sidewalk fruit vendors. The Journal of contemporary health law and policy. 2009 Fall;26(1):20–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raijman R. Mexican immigrants and informal self-employment in Chicago. Human Organization. 2001;60:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raijman R, Tienda M. Immigrants’ pathways to business ownership: a comparative ethnic perspective. Int Migration Rev. 2000;34(3):682–706. [Google Scholar]