Abstract

This article profiles bereavement among traumatized Cambodian refugees and explores the validity of a model of how grief and PTSD interact in this group to form a unique bereavement ontology, a model in which dreams of the dead play a crucial role. Several studies were conducted at a psychiatric clinic treating Cambodian refugees who survived the Pol Pot genocide. Key findings included that Pol Pot deaths were made even more deeply disturbing owing to cultural ideas about “bad death” and the consequences of not performing mortuary rites; that pained recall of the dead in the last month was common (76% of patients) and usually caused great emotional and somatic distress; that severity of pained recall of the dead was strongly associated with PTSD severity (r = .62); that pained recall was very often triggered by dreaming about the dead, usually of someone who died in the Pol Pot period; and that Cambodians have a complex system of interpretation of dreams of the deceased that frequently causes those dreams to give rise to great distress. Cases are provided that further illustrate the centrality of dreams of the dead in the Cambodian experiencing of grief and PTSD. The article shows that not assessing dreams and concerns about the spiritual status of the deceased in the evaluation of bereavement results in “category truncation,” i.e., a lack of content validity, a form of category fallacy.

Keywords: grief, complicated bereavement, mass trauma, Cambodia, PTSD

A rich anthropology literature exists on burial rituals and death-related beliefs in a variety of cultural contexts. That literature shows a great diversity in beliefs about what happens to the deceased after death, how the manner of death influences rebirth, whether the deceased remains in contact with the living, what rituals need to be performed for the deceased, and whether the deceased brings about luck or misfortune and in what circumstances (Brison 1995; Brison and Leavitt 1995; Leavitt 1995; Woodrick 1995). But few studies examine from an anthropological perspective the state of remorse and longing that sometimes continues after that death and how those who have pained recall of the deceased try to overcome that state (Hollan 1995; Robben 2004; Wikan 1988). Few studies have investigated the particular sociocultural course of bereavement processes in other cultural contexts and how it may vary across cultures. And there has been minimal study of how bereavement issues play out differently in cultural groups exposed to mass violence.

Cambodian refugees typically had multiple relatives die in the Pol Pot period (1975–1975). It is estimated that a quarter of the population died by starvation, illness, and execution during that time period (Chandler 1999). Those targeted for execution included anyone who was perceived to be lazy in work habits; who tried to obtain food outside of the allotted daily meals, for example, even picking a single fruit, though all were starving to death; who could read or write; who had been a soldier or official; or who had Chinese or Vietnamese ancestry. Execution was often by a blow to the back of the head, the body dumped in a mass burial pit. Even if the body could be located, it was impossible to perform the culturally indicated mortuary rituals such as cremation because the Khmer Rouge banned religion and all death-related rituals so that at best a shallow burial was possible.

Complicated grief is being considered for inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5; Shear, et al. 2011), although the diagnostic criteria have not been finalized.i This makes it all the more important to determine to what extent the currently proposed criteria capture the core experience of complicated bereavement in other cultural contexts. In our clinical experience, certain key aspects of complicated grief are not in the proposed criteria (on the criteria, see Simon, et al. 2011).ii For one, the criteria do not include the person's concerns about the spiritual status of the deceased. But in the Cambodian culture and many others, it is thought that if certain burial and post-burial rituals are not performed, for example, owing to genocide and mass violence, then the dead may not move on to the next spiritual level to become spiritual helpers but instead may roam the earth in a wretched state and pose a danger to the living. Clearly these types of concerns about the spiritual state of the deceased will affect the bereavement process. And second, the proposed DSM-5 criteria for complicated grief do not include dreams of the dead, but we have noted in our work with Cambodian refugees that dreams in which the dead are encountered play a key role in mourning because they are common and because they are thought to indicate an actual interaction with the spirit of the deceased (Hinton, et al. 2009).

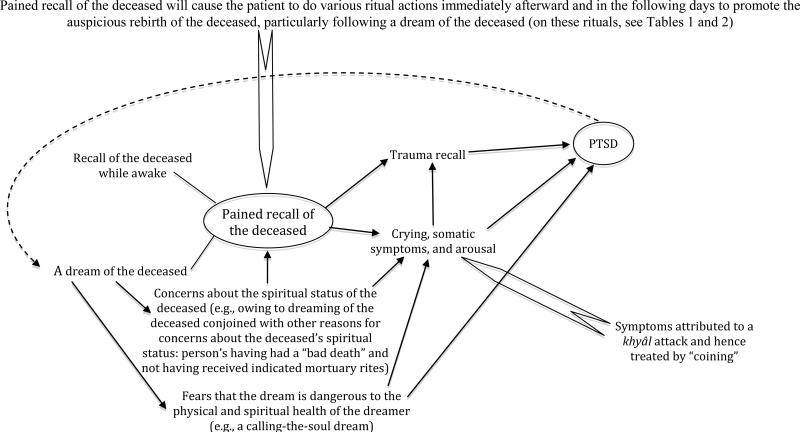

In this article, we examine bereavement in cultural context through four studies among Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic. These four studies explore the Cambodian bereavement ontology through the investigation of the validity of a model of how pained recall of the deceased interacts with PTSD in this group, a model that highlights the role of dreams of the deceased (see Figure 1). Study I delineates the number of deaths patients have endured and how many occurred in the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia (1975–1979), focusing on first-degree relatives, and it determines whether patients are currently separated by great distance from many relatives owing to their living in Cambodia, increasing the sense of loss. Given that most of those who died in the Pol Pot period died a horrible death and did not have culturally indicated death rituals, Study II investigates cultural ideas about the spiritual state of the deceased and rituals needed to assure auspicious rebirth. Using a bereavement questionnaire and an assessment of PTSD severity, Study III profiles bereavement and explores the validity of the Bereavement–PTSD Model (Figure 1) by examining several of its aspects: the hypothesized high correlation between pained recall and PTSD severity, the triggering of pained recall by a dream, pained recall's bringing about of severe distress like crying and somatic symptoms, and pained recall's triggering of trauma memories. Lastly, Study IV investigates dreams of the deceased, including subtypes, to examine why the dreams cause great distress, and it elicits detailed cases of bereavement that involve dreams.

Figure 1.

Bereavement – PTSD Model as Applied to the Cambodian Genocide Survivor: The Central Role of Dreams. This model shows how bereavement and PT SD mutually worsen one another and the key role of dreams of the deceased in this process. Pained recall of the deceased may occ ur while awake or while dreaming. Dreams of the deceased will give rise not only to concerns about the spiritual status of the deceased but also to fears that the dream is dangerous to the dreamer, e.g., if the dreamer follows the deceased in the dream, the dreamer's soul may be permanently displaced from the body.

Recall of the deceased will cause trauma recall by several mechanisms: (1) by bringing to mind the manner of the person's dea th, for example, having seen a parent taken away to be killed by the Kh mer Rouge, which may then evoke various trauma events; (2) by evoking a sense of loss and sadness, for example, the sense of loss owing to the person's death, which will recall other losses; (3) by causing concerns about the spiritual state of the deceased; (4) by evoking the Pol Pot period if the recall is a dream in which the relative seems hungry or suffering in some way that resembles conditions in the Pol Pot period; (5) by creating a sense of imminent danger, for example, if the recall is a dream that is thought to be dangerous; and (6) by bringing about somatic symptoms and dysphoria that then trigger trauma recall, such as when palpitations recall trauma memories encoded in memory by that somatic symptom.

Thus, recall of the deceased will result in trauma recall, arousal, and fear, all of which will worsen PTSD. Worsened PTSD will result in more nightmares, which may take the form of dreams of the deceased, creating a vicious cycle of worsening. Somatic symptoms and distress cause d by recall of the d eceased will tend to be attributed to a khyâl attack and will be treated by coining. Owing to concerns about the spiritual status of the deceased, the patient may do vario us ritual actions both immediately after recall of the deceased and in the following days to promote the auspicious rebirth of the deceased.

The four studies were conducted in an outpatient clinic in Lowell, Massachusetts, and all participants were being treated by the first author, who is fluent in Cambodian. Lowell is home to over 30,000 Cambodian refugees. The vast majority of patients (over 95%) present to the clinic with PTSD, and all are survivors of the Pol Pot period (1975–1979). In previous surveys, we have found that about 50% of patients continue to have PTSD (Hinton, et al. 2011). At the clinic, 65% of the patients are women. Most patients at the clinic (over 90%) were rice farmers in the Pol Pot period and have minimal education and very little English ability. Most patients (over 85%) are not currently working, spending their time caring for children and grandchildren. The mean age of patients at the clinics is 49.4 (SD = 6.1), and for the survey we only assessed patients who were at least 6-years-old at the beginning of the Pol Pot period.

Study I: Number of Deceased First-Degree Relatives and Time of Death

We created family trees of 100 patients at the clinic to determine how many relatives each had lost in the Pol Pot and other time periods. Each patient had lost a mean of 1.7 parents (SD = 0.5), 2.1 siblings (SD = 1.9), and 0.8 children (SD = 1.4),iii and the majority of these deaths had occurred in the Pol Pot period: 51% of parental deaths, 82% of sibling deaths, and 78% of child deaths. Many still had first-degree family members living in Cambodia: a mean of 0.2 (SD = 0.4) parents and 1.6 (SD = 2.1) siblings. Thus many participants were separated by death or great distance from a mean of 1.9 parents and 3.7 siblings (out of a mean of 5.0 siblings).

Study II: Cambodian Ideas about the Spiritual State of the Deceased and Rituals Needed to Facilitate an Auspicious Rebirth

We used a semi-structured interview to query patients regarding their ideas about the spiritual state of the deceased and the rituals needed to facilitate auspicious rebirth because these form key parts of our model of bereavement (see Figure 1). Given that essentially all religious activities and traditional ceremonies for the deceased could not be performed in the Pol Pot period owing to the Buddhist religion being banned and all monks being forcibly disrobed, it is important to examine the meaning of these activities to understand the emotional impact on surviving family members of their omission. Also, examining the rituals Cambodians currently perform to improve the spiritual state of the deceased reveals their conceptualization of the state of the deceased and the relationship of the living with the deceased, and these ideas about the spiritual state of the dead and indicated rituals form key aspects of the bereavement ontology of the Cambodian genocide survivor as indicated in Figure 1.

Ideas about the Spiritual State of the Deceased

“Bad death” (Tdaay haong)

According to patients and traditional Cambodian belief, dying any violent or difficult death such as being killed by someone or being in a car accident is a “bad death” (tdaay haong) and indicates that the deceased may have some past “demerit” that may well prevent rapid rebirth. (According to Buddhism, merit results from good actions and demerit from bad actions and both merit and demerit are maintained across reincarnations.) Traditionally someone dying a “bad death” would only be cremated after being buried for a few years in order to “cool the inauspiciousness,”iv a practice still maintained in Cambodia but not in Lowell. The victim of a “bad death” is thought to wander in a purgatory state and often to be a hostile ghost wreaking havoc on the living. Most deaths occurring during the Pol Pot period were considered “bad deaths” because they involved death by execution or starvation, and worse yet, even after the Pol Pot period, often the bodies could not be found to perform delayed cremation.

Rebirth

Cremation and other post-mortuary rites (see Table 1) normally result in rebirth within one year after death, and often by the time of the 100-day merit-making ceremony. Rebirth results in the deceased's moving into a new spiritual state, and the state depends on the deceased's “merit level”: the deceased may be reborn as a lower being like a dog, as a baby in a difficult or an “auspicious” life, or as a god. But rebirth may not occur by one year for four main reasons: (1) The deceased may have accrued much demerit as a result of having done bad deeds in this life or a previous one, such as hurting others or killing animals. (2) The deceased may have had a “bad death” owing to accrued demerit and that demerit will delay rebirth, particularly if the body could not be found to perform delayed cremation.v (3) The deceased may not have had the indicated rituals performed following death to increase “merit” and promote rebirth such as chanting, ritual gift-giving, and cremation (see Table 1). And (4) the deceased may miss living relatives too much and so refuse to be reborn. For reasons 2–4, those who died in the Pol Pot period were unlikely to be reborn, namely, they often had a bad death, dying of execution or starvation; they often did not have any death rituals performed because the Khmer Rouge prohibited them, with bodies at best being given a burial in a shallow pit; and they often long for living relatives, because during the Pol Pot period the Khmer Rouge forcibly separated family members, with even young children sent to work far from parents.

Table 1.

Rituals Done in the Year Following Death to Promote Rebirth and Improve Spiritual Status

| Initial Chanting and Vigil | In Cambodia, the deceased is usually placed in the family home after death, and monks are invited to do chanting that lasts through the night. Some of this chanting is especially emotionally moving because of the strong, crying-like vibrato. The chanting is thought to help the deceased to attain an auspicious rebirth. In Lowell, MA, after the body is released, it is placed at the temple where the monks perform the traditional chanting. |

| Gift-Bestowal Ritual (Bangsoekool) in the First Week | Each morning for the first seven days following death, ideally relatives and friends will give donations to the monks in the “gift-bestowal ritual” (see Table 2), a ritual that aims to make “merit” for the deceased and send to him or her needed items like food. When doing the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple, the monk typically announces to the deceased at some point, “Go be reborn to a new life, don't hang around here with your relatives.” This exhortation and the ritual are supposed to encourage the deceased to be reborn rather than remain in this world with loved ones. |

| “Becoming a Monk Before the Fire” (bueh muk phleung) | For a few days before cremation, ideally male relatives—sons, grandsons, nephews—will temporarily serve as monks, which is called “becoming a monk in front of the fire” (bueh muk phleung). Becoming a monk entails going through an initiation ceremony that includes shaving the head, and the newly initiated monk lives in the temple and dresses and acts like a monk, such as eating only once a day before noon, the meal consisting of the food that is donated by laypersons. Becoming a monk makes merit and that merit is shared with the deceased to promote their auspicious rebirth. This tradition is still common in Lowell, MA. |

| Cremation | A few days after death, cremation is done. Traditionally, family members collect the ashes that remain after cremation and put them in a basket, then clean the ashes with coconut juice that symbolizes purity. (The coconut is usually cut on the spot.) A family member carries the ashes on the head in a basket; the liquid that drops on the head is thought to convey blessing. (Water and cool are highly associated with auspiciousness in the Cambodian cultural context.) The ashes may be sprayed with perfume and wrapped in a white cloth. Family members should attend the cremation to show respect and receive the blessings of the deceased. A relative who is unable to attend this event may later say with great emotion, “I was unable to see the smoke of the cremation fire” (ot kheuny psaeng pleung). These rituals are still performed in Cambodia, but not in Lowell; in Lowell, cremation is done at a crematorium. |

| Urn and Its Placement | After cremation, the ashes are placed in a small stupa-shaped metal urn, which is about a foot high, and ideally this is kept in a larger stupa that is about ten feet high and built next to a temple; but usually the urn is stored in the temple because of the considerable cost of building a mortuary stupa. These urns can be taken out and made offerings to. In Lowell, usually these urns are stored at the temple, but if family members are concerned about the spiritual status of the deceased, they may build a stupa in the deceased's home village in Cambodia. |

| Remembering-the-Dead Ceremonies at Seven Days, 100 Days, and One Year | On the seventh day after death, the deceased realizes he or she has died, so that it is crucially important to do the gift-bestowal ritual on that very day, a ceremony called “crossing merit” (bon cheulâng). This ceremony helps the deceased to cross to the other side to rebirth. On this seventh day, ritual relatives will offer to the monks during the gift-bestowal ritual anything the deceased needs to make the journey to the next life such as food, dishes, mat, money, umbrella. A similar ceremony is performed at 100 days and at one year after death. |

| Various rituals that can be done in the first and following years | See Table 2. |

Thus, Cambodians worry that the Pol Pot dead are not reborn and that they wander the earth in a purgatory-like state, and moreover they believe that those who have not attained rebirth may only do so through the merit-making of their relatives or through suffering while wandering the earth, with suffering having the power to eliminate demerit. For a description of the merit-making and other rituals that relatives may perform to provide succor to and promote rebirth of those not reborn after one year, see Table 2: one of the most important merit-making rituals that relatives perform is bangsoekool, which we will henceforth call the “gift-bestowal ritual” (for a description of the gift-bestowal ritual [bangsoekool], see Table 2). The “gift-bestowal ritual” (bangsoekool) results in the sending of merit, as well as other donated items such as food and clothing, to those not yet reborn in order to promote their rebirth and to provide relief while they remain in a purgatory state. If the deceased died a “bad death,” rebirth may require that relatives perform not only merit-making but also actual or symbolic cremation in the case that cremation has not been done (for a description of delayed and symbolic cremation, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Rituals Done After One Year to Promote Rebirth and Improve Spiritual Status

| The Gift-Bestowal Ritual (Bangsoekool) | The “gift-bestowal ritual” (bangsoekool) is a special merit-making ritual during which items are given to monks at the temple, and then these objects—along with the merit made by doing this religious act—are said to reach the deceased to whom they are dedicated. Most often food is given, but also money, clothes, or other objects. The act of giving these objects to the deceased has deep emotional meaning, particularly if the death occurred during the Pol Pot period, because in the Pol Pot period food, clothing, and other essentials were severely lacking. To perform the gift-bestowal ritual, the names of deceased relatives are written on a piece paper. This paper along with offerings are given to the monks at the temple. The monk does a blessing with chanting and asks that the merit and objects reach the deceased. The monk's helper burns the pieces of the paper on which the name has been written, sending the blessings and items to the deceased in rising smoke. Next the helper pours water on the pieces of paper while each layperson also pours water into a small bowl. This pouring symbolizes that the “cooling” merit the person has made that will now reach the dead. (This putting out of a flame with water has deep resonances in the Cambodian culture: it represents the extinguishing of the hot fire of suffering and it recalls one of the most important Buddhist events that is extensively represented in Cambodian Buddhism, viz., the mother goddess washing away Mara and his demons with water wrung from her hair with that water representing all the merit the Buddha has made in his many lives.) The ritual can be done at any time, for example, after having a nightmare of the deceased, and the ritual can be tailored to the perceived needs of the deceased: if one dreams that the deceased lacks clothes or food, these may be given to the monks. As indicated in Table 1, the “gift-bestowal ritual” should be done for the deceased at seven days, at 100 days, and at one year. It is also an important part of two yearly societal-wide rituals aiming to make merit for the deceased, viz., New Years and Pheuchum Beun. |

| Merit-Making for the Dead: Chanting, Meditation, and Other Good Deeds | Merit is thought to be a supernatural spiritual substance that helps the dead to be reborn to a higher plane and ease their suffering; it has an erasing effect on bad merit that was accumulated from bad deeds in the past. Merit is made by making donations to the monks, doing good deeds, and performing any other religious act such as meditating. Some patients do chanting each evening or meditation (usually by attending to the breath) and share that merit with the deceased. After performing any merit-making activity, patients usually share the merit by doing the following: they raise the hands in front of the face with the finger tips pressed together to make a lotus form, then bend over at the head, and next ask that the merit they just made be sent to that deceased person. Even if a relative has been reborn, there is a sense that these rituals bestow blessings on them, and help to ensure their success in their new life after rebirth. |

| Food Offerings at the Home | Cambodians almost always have an altar where offerings are presented to the Buddha and deceased relatives. A Buddha image is placed on an elevated shelf and below it are often set family pictures. Food offerings—such as a fruit or some small portion of food from the meal being eaten that day—can be presented to the deceased at the altar, and so too flowers and a glass of fresh water. Upon giving food and other items to the deceased relative at the altar, Cambodians often light candles and incense sticks on the Buddha shelf in order to guide the deceased to the offering, and they may spray the altar with perfume. They may say something like the following, particularly if they recently dreamed of a relative: “Please take this food, and be reborn. Please do not keep circling around the living, be reborn.” Food and flowers are often offered at the home altar on Buddhist holy days (no moon, quarter moon, half moon, full moon), and some patients offer food every day that is taken from that day's meal. |

| Recalling-with-gratitude Ritual (nuk kun): A Home-Based Memorialization Ritual | Almost all Cambodian patients at the clinic regularly do a ritual called “recalling with gratitude” (nuk kun). It involves evoking positive memories of the deceased, particularly parents. To do this ritual, first one lights candles and incense on the home altar, then three times makes a devotional prostration—a kowtow-like motion but with the hands kept in a lotus form in front of the face—in obeisance to the Buddha and relatives. Next one puts the hands in front of the face in the lotus shape, and bends over the head against them. While in this bent-head position, one should think with gratitude towards the Buddha, his teachings, and monks, the so-called “three jewels”; next one should think of one's parents and others who have provide succor and all the while maintain the emotion of gratitude; ideally one should visualize one's parents while thinking about the particular acts of goodness they have done for one, such as one's mother nursing one or preparing meals. This ritual is supposed to have several effects. It helps one's own merit status, because one is acting with gratitude towards the good acts of others, which is considered a key virtue. Also, one is gaining protection by evoking these positive forces, that is, the Buddha, his teachings, the monks, and one's parent or parents, and additionally these positive forces help one to maintain virtuous actions. Finally, the recalling-with-gratitude ritual makes merit for the deceased; one is evoking the memory of that person's good actions, which increases their merit. Some patients mentioned that they acquired information about the deceased's spiritual state while doing the recalling-with-gratitude ritual: they would suddenly see the deceased in a dire state, such as being hungry or poorly dressed, indicating their dire spiritual status and their need for merit to be made for them. |

| Building a Stupa for the Deceased | After death, or in the following years, the urn of the deceased may be placed in a stupa, which is often about ten feet high, and that may have a special Buddha image in its upper portion or even a Buddha relic. The large stupa creates a sort of field of merit and placement in it helps the spiritual state of the deceased. |

| Other Large Scale Donation Ceremonies for the Deceased | Typical merit-making rituals would be giving alms to the poor at the temple in Cambodia, donating a pond or building to a temple, or performing the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple by presenting gifts to the monks. Often Cambodians make videos of these events to show relatives in the United States and to keep as a memento. One of these ceremonies is called “remembering the soul of the deceased” (rumluk winyeukhaan) and is centered on the gift-bestowal ritual but includes additional chanting. |

| Chhaa bangsoekool (bringing-out, gift-bestowal ritual) | In Lowell and other Cambodian communities in the United States, as well as in Cambodia itself, a traditional ritual is now sometimes performed but with a broadened aim. The traditional ritual is called “remembering the soul of the deceased” (rumluk winyieunakhaan) and was originally done for one deceased person represented by a corpse or by an ash-filled cremation urn. Now the rite has a broader range. All the urns at the temple are taken out and put on a table, and participants can either bring a picture of a relative who has died or simply conjure in mind the deceased while the ceremony is being performed. After chanting for about three hours, the monks anoint the urns with lustral water. The ceremony gives blessing to all the deceased conjured in the ceremony. |

| Delayed Actual Cremation and Symbolic Cremation | Those who died in the Pol Pot period never had cremation performed, and if there any indications that the person has not been reincarnated, such as a family member dreaming of the deceased, various rituals may be performed. If the body cannot be found to do cremation, monks can perform a ceremony in which the deceased's soul is transferred into a handful of soil, which is then deposited in the urn. To do the burial ceremonies and create the stupa may cost several thousand dollars. Many patients are upset about not being able to afford these rites and believe the deceased has not been reborn for this reason. After doing such rites, which are often done owing to having dreams of a deceased relative indicating they have not been reborn, frequently patients have a great decrease of bereavement, dreams of the dead, posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, and somatic complaints. |

Dreams of the dead as spiritual status indicators

Dreams are the main way that Cambodians determine whether someone has been reborn and the main way that Cambodians ascertain the spiritual status of those who have not been reborn. Dreams are considered to result from the experiences of the dreamer's soul as it wanders in the world. Encountering a dead person's spirit in a dream reveals that that person has not yet attained rebirth. When a friend or relative dies, patients carefully attend to such dreams and family members share these dreams to exchange information about the spiritual status of the deceased. In the first year after death such dreams are frequently not considered dangerous but rather comfortingvi; however, in some cases, these dream may be disturbing, for example, if in the dream the deceased wears tattered or dirtied clothing and looks emaciated and distressed, all indictors of a dire spiritual status.

After the one-year death anniversary, dreaming of the deceased is usually very upsetting because it indicates that the deceased has not been reborn and wanders the earth as a ghost and because it is considered to be an actual, potentially dangerous encounter with the dead. Before two yearly holidays that involve making merit for the deceased, dreaming of the dead is more common; this is because relatives who have not been reborn visit living relatives in their dreams to remind those relatives to make “merit” for them during the two holidays, namely, Cambodian New Year and Pheuchum Beun.vii Of the two holidays, dreams of the dead are particularly common before Pheuchum Beun, a holiday exclusively devoted to the deceased, a sort of Cambodian All Souls’ Day: during the three days of Pheuchum Beun, the still-not-reborn are thought to come to the temple to receive “merit” as well as a special rice food and other items that are sent to them through the “gift-bestowal ritual” (bangsoekool) and various other ritual means.

Rituals Done to Assure the Auspicious Rebirth of the Deceased

Rituals Done in the First Year to Promote Rebirth and Improve Spiritual Status

Rituals that should be performed in the first year following death for the deceased are described in chronological order in Table 1.viii

Rituals Done After One Year to Promote Rebirth and Improve Spiritual Status

If there are concerns that the deceased has not been reborn after one year—for example, owing to a living relative's dreaming of the deceased or owing to the deceased's having died a bad death or not having had after death the indicated rituals—then certain rituals should be performed. For a description of those rituals, see Table 2, one of which, chaa bangsegoul, was only recently developed to deal with genocide losses.

Two Yearly Holidays Having Rituals for the Dead: Cambodian New Year and Pheuchum Beun (Cambodian All Souls’ Day)

The Cambodian New Year, which occurs from April 12–14, is not exclusively dedicated to making merit for the deceased, but during it families do the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple (on the gift-bestowal ritual, see Table 2). The Pheuchum Beun holiday, what might be called Cambodian All Souls’ Day, specifically aims to make merit for dead relatives. It occurs for three days in early October, during which the dead who have not been reborn come to the temple seeking merit, food, and other offerings.ix The most important Pheuchum Beun activity is the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple, which sends merit, food, clothes, and other items to the deceased (see Table 2), and almost every Cambodian participates in this ritual during one of the three mornings. As compared to New Year's, the gift-bestowal ritual is more elaborated in Pheuchum Beun and involves about an hour of chanting that starts around 10 a.m.x As another Pheuchum Beun activity, at dawn Cambodians place balls of sticky rice mixed with sesame seeds outside the temple, often under a tree, as an offering to the dead. To guide the dead to this offering, into each rice ball is inserted a lit candle, a lit joss stick, and a “spirit flag” that is made by attaching a small triangular flag on a short stick. As a home-based ritual during Pheuchum Beun, Cambodians place a favorite food and beverage of the deceased on a table in the home, and next to them light a candle and a joss sticks; after lighting these, the celebrant asks that his or her parents and all other relatives receive the food and be reborn on a higher spiritual level.xi

Study III: Profiling Bereavement with the Bereavement Questionnaire and Exploring the Validity of the Bereavement–PTSD Model in a Traumatized Cambodian Sample

Using a Bereavement Questionnaire (Table 3) and an assessment of PTSD severity, Study III profiled bereavement and aimed to explore the validity of many components of the Bereavement–PTSD Model (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Bereavement Questionnaire: Profiling Bereavement among Cambodian Patients at a Clinic who had Pained Recall of the Dead in the Last Month (n = 76)

| Type of Assessed Item | Assessed domain | Level of Severity, Frequency, Percentage, or Number of Years |

|---|---|---|

| •Person most painfully recalled and time of death• | Person most painfully recalled | Parent = 46% Sibling = 29% Child = 15% Spouse = 6% Other = 4% |

| Time since death of the person who was most painfully recalled | M = 28.9 years (SD = 11.9) | |

| Percentage of person's most painfully recalled who died in the Pol Pot period | Pol Pot = 69% | |

| •Self-perceived severity of pained recal• | Self-perceived severity of pained recall in last month (“In the last month, how unwell did you feel in the body or mind upon recalling the deceased?”) | Quite a lot unwell = 41% Somewhat unwell = 31% A little unwell = 28% |

| •Frequency of pained recal• | Frequency of episodes of pained recall of the dead in the last month | M = 5.1/month (SD = 4.1) |

| •Dreams and pained recal• | Number of upsetting dreams of the deceased in the last month | M = 2.4/month (SD = 3.2) |

| Percentage of episodes of pained recall in the last month caused by a dream | 47% (2.4/5.1) | |

| Percentage of patients with pained recall in the last month having painful dreams of the deceased in the last month | 71% (68/76) | |

| The number of upsetting dreams of the deceased in the last month among those having such dreams | M = 2.8/month (SD = 3.1) | |

| •Spiritual concerns• | Among those with painful recall, severity of concern that the person painfully recalled is not reborn | Extremely = 26% Much = 24% Somewhat = 22% A little = 18% Not = 10% |

| •Crying during pained recall• | Percentage crying upon having pained recall | 73% (58/76) |

| Among those who cried during pained recall, the average number of crying episodes in the last month | M = 4.2/month (SD = 3.2) | |

| Length of crying episodes | M = 11.0 min (SD = 12.1) | |

| •Somatic distress and pained recall• | Percentage of patients who had enough symptoms to qualify as a panic attack during the episode of pained recall | 91% (69/76) |

| Mean severity of blurry vision in the last month (0–4 Likert-type scale from “none” to “extremely”) | M = 2.3 (SD = 1.3) | |

| Mean severity of dizziness in the last month (0–4 Likert-type scale from “none” to “extremely”) | M = 2.1 (SD = 1.1) | |

| •Trauma recall and pained recall• | Percentage of patients having trauma recall during pained recall in the last month | 90% (68/76) |

| Percentage of patients having flashbacks during pained recall in the last month | 62% (47/76) | |

| •Culturally specific labeling and treatment of particular episodes of pained recall• | Percentage of patients who attributed the somatic and emotional distress caused by pained recall to a khyâl attack | 70% (53/76) |

| Percentage of patient who had a khyâl attack who coined | 78% (41/53) | |

| Percentage of patients who did coining who had others do coining | 74% (30/41) | |

| Percentage of patients who did coining who had others do coining who told the coiner the reason for distress | 90% (27/30) |

Methods

As the bereavement screen, we asked patients, “In the last month, did you recall in a pained way a deceased relative to the point that it made you feel not well in your body or mind.” If present, bereavement was profiled using the items in the Bereavement Questionnaire, outlined in Table 3. As noted in Table 3, we assessed severity of blurry vision and dizziness. We did so because a previous study had shown a high correlation of bereavement to blurry vision in the last month (Caspi, et al. 1998). Not shown in Table 3, we asked whether certain somatic symptoms were induced by recall of the deceased, including DSM-IV panic attack symptoms and others somatic symptoms that we have found to be commonly induced by such nostalgic recall, namely, headache, low energy, tinnitus, and blurry vision. To assess for “flashback,” we determined whether the recall was more vivid than simply thinking about it by asking, “Did you simply think about the event, or did you see it freshly again, like it was happening again?” If so, patients were asked to describe the recall to assure that it was indeed a flashback, investigating for the presence of multisensorial reliving.

As shown in Table 3, to assess the cultural interpretations of the distress and symptoms triggered by painful recall, we asked patients whether pained recall in the last month had caused a khyâl attack, which might be translated as a “wind attack” (Hinton, et al. 2010). Cambodians often consider that psychological distress and anxiety-type somatic symptoms are caused by a disturbance of the flow of khyâl, a wind-like substance thought to flow alongside blood. They fear that the blockages of flow of khyâl and blood may result in cold extremities and “death of the limbs,” that is, stroke, and that unable to flow downward through the limbs, the khyâl and blood may surge upward in the body to cause shortness of breath and asphyxia; palpitations and heart arrest; and tinnitus, blurry vision, and dizziness, along with fatal syncope. As also shown in Table 3, we asked about “coining.” Cambodians treat khyâl attacks by “coining.” This entails dipping the edge of the coin in “wind oil,” that is, khyâl oil, a camphor-containing liquid that has a warming quality, and pushing the edge down on the skin; the edge is then dragged across the ribs in the front and back and outward down the limbs, producing linear red marks. “Coining” is thought to restore warmth to the body and promote proper flow of khyâl and blood. Others are often asked to do the coining.

To determine PTSD severity, we used the PTSD checklist (PCL), which rates PTSD severity on a 1–5 Likert-type scale. The PCL assesses how much each of the 17 DSM–IV PTSD criteria has bothered the patient in the last month, each assessed on a 1–5 Likert-type scale: 1 (“not at all”), 2 (“a little bit”), 3 (“moderately”), 4 (“quite a bit”), and 5 (“extremely”). The PCL has shown excellent psychometric properties (Wittchen, et al. 1998). The Cambodian version of the PCL has excellent test–retest and inter-rater reliability (r = .91 and .95, respectively).

Results

Percentage of Patients with Pained Recall, Who was Most Painfully Recalled, and Time Period of Death

As shown in Table 3, most (76%) patients had pained remembrance of a deceased relative or friend in the last month, and the person most frequently recalled in this way was a parent. Most of these deaths occurred in the Pol Pot period (69%).

Severity of Pained Recall and PTSD and Their Correlation

Among all patients (N = 100), 55% were either “quite a lot bothered” or “somewhat bothered” by thinking about the deceased in the last month, suggesting considerable bereavement-related distress (Table 3). In the entire sample, the mean per item score of the PCL was 2.3 (SD = 0.9), and the severity of pained recall of the deceased was highly correlated to the severity of PTSD in the last month (r = .62, p < .001), so that 38% of the variance in PTSD severity was explained by this one-item assessment of bereavement distress. In the group with pained recall of the deceased (n = 76), the mean PCL score was 2.6 (SD = .78), whereas in the group without pained recall (n = 24), it was 1.5 (SD = .74), a highly significant difference (t = 5.5, p < .001).

Frequency of Pained Recall and Frequency of Pained Recall Caused by Dream

Those having pained recall of the dead in the last month had about five such recall episodes in the last month, of which about half were triggered by dreaming of the deceased (see Table 3). Those having painful dreams of the dead in the last month had a mean of 2.8 (SD = 3.1) such dreams in the last month.

Concerns about the Spiritual Status of Those Painfully Recalled

Concerns that the deceased was not reborn were elevated among those having pained recall of the deceased in the last month: 72% were “somewhat concerned” or more (Table 3), And among those having pained recall in the last month, the degree of concern that the person was not reborn was highly correlated to the frequency of dreams of the deceased in the last month, r = .71, p < .001.

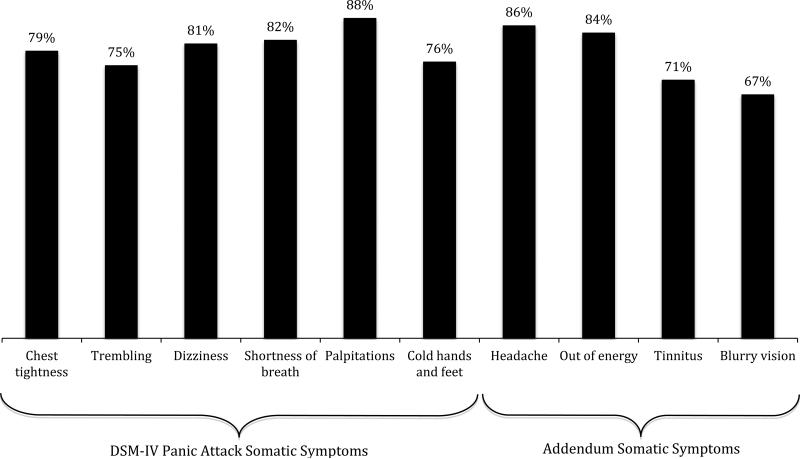

Crying and Somatic Symptoms during Episodes of Pained Recall

Crying was experienced by 73% (58/76) of the patients with pained recall of the dead upon thinking of the deceased in the previous month (Table 3). Those who cried during pained recall had a mean of about four episodes in the previous month, each crying episode lasting about ten minutes. Not only crying but also multiple somatic symptoms, including such symptoms as palpitations, tinnitus, and headache, were caused by recall episodes, as is shown in Figure 2. The number of somatic symptoms induced was usually sufficient to met panic attack criteria (Table 3). As also shown in Table 3, blurry vision and dizziness were common in the bereavement group in the previous month. Doing further analysis, we found that in the group with pained recall, the mean severity of blurry vision in the last month (M = 2.3, SD = 1.3) was much greater than in the group without pained recall (M = 0.3, SD = 0.6), which was highly significant (t = 6.6. p < .001). We also found that the mean severity of dizziness in the last month in the group with pained recall (M = 2.1, SD = 1.1) was much greater than in the group without pained recall (M = 0.4, SD = 0.7), which was highly significant (t = 9.9, p < .001). We also found that in the entire sample that severity of blurry vision in the last month was highly correlated to severity of pained recall (r = .66, p < .001), and so too dizziness to pained recall (r = .56, p < .001).

Figure 2.

Frequency of panic and other somatic symptoms experienced by Cambodians upon recalling deceased relatives in the last month

Trauma Recall During Episodes of Pained Recall

Past traumas were brought to mind by pained recall of the dead among 90% (68/76) of patients with pained recall (Table 3), and the recalled trauma almost always was an event that occurred in the Pol Pot period. Trauma recall that was a flashback—typical flashbacks included reliving doing hard labor while starving and observing a relative being arrested, killed, or dying of starvation and illness—was found for 62% of patients, and often patients reported having serial flashbacks.

Treatment of Episodes of Pained Recall

Distress and somatic distress triggered by pained recall were attributed to a khyâl attack by 70% (53/76) of patients with such recall (Table 3). (Often the khyâl episode was thought to be caused by the emotional upset caused by the pained recall of the dead.) Of those patients so labeling the emotional and somatic distress, the majority (78%) did coining whereas others relied on alternative methods to treat khyâl such as applying “wind oil” (preing khyâl) to the body. Often patients had others do coining and almost always told the coiner that they had not been well because of pained recall of the deceased relative.

Study IV: Dreams of the Dead: Subtypes and Cases

The Bereavement–PTSD Model (see Figure 1) hypothesizes dreams to be a central aspect of bereavement among Cambodian refugees, and Study IV further investigates this by assessing the frequency of dreams of the deceased, who was dreamed about, and the types of dreams of the deceased, in particular focusing on what the dreams are supposed to indicate about the spiritual state of the deceased and the danger of the dream to the dreamer.

Methods

Fifty consecutive patients who endorsed having both pained recall of the deceased and dreams of the deceased in the last month were asked how often they had had such dreams in the last month. Then for each of these dreams, the patients were asked who they dreamed about and when the person had died, and they were asked about the content of the dream. Content was analyzed to determine the types of dreams. When a preliminary typology was determined, patients were queried to verify the validity of the types and to determine their ideas about the types of dreams. Finally cases were written up.

Results

Frequency of Dreams of the Dead

The mean number of dreams of the dead in the last month was 2.1 (SD = 1.5).

Relationship to the Person Dreamed About

The deceased person most commonly seen in a dream was a parent (56%), next a sibling (30%), and then at much lower rates, a child (6%) or spouse (6%).xii

When the Person Who Was Dreamed about Had Died

Most dreams (80%) involved people who died in the Pol Pot period (1975–1979), whereas 2% involved someone who died before the Pol Pot period and 18% someone who had died after the Pol Pot period.

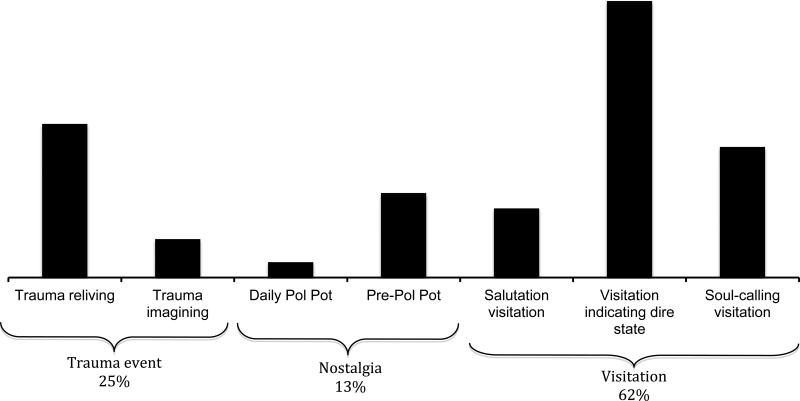

Types of Dreams of the Dead

The 140 dreams of the deceased that were reported by the 50 patients could be categorized in three categories, namely, “visitation,” “nostalgia,” and “trauma,” each of which had subtypes. The frequency of these types and subtypes of dreams are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Types and subtypes of dreams of the deceased among Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatry clinic (based on the analysis of 140 dreams)

Visitation dreams

These were the most common and constituted 62% of all dreams. Visitation dreams are thought to occur when the soul of the deceased comes to visit the dreamer's soul as it wanders during sleep. These visitations are deeply disturbing because they indicate the deceased is not reborn and because they involve encountering a ghost. The dreams are of three subtypes, each of which has progressively greater perceived dangerousness.

“Salutation visitation.” In these types of dreams, the deceased came to see the patient but the deceased was not distressed, for example, the deceased was not overly thin, didn't cry, and wore normal clothes. Often the deceased said he or she simply came to visit the dreamer and asked how the patient was doing. Often the visitor was a parent.

“Visitation indicating dire spiritual state.” In these dreams, the deceased revealed him- or herself to be in a distressed state in the following ways: the deceased specifically asked the dreamer to make merit for him or her or to send an offering of some particular needed item like food or else the deceased looked emaciated, had tattered clothes, or was crying. Further analysis of the 50 dreams of this type revealed that in 24% (12/50) of them that the deceased requested merit-making, in 32% (16/50) the deceased asked for food, in 28% (14/50) the deceased wore tattered clothes, often looking cold, in 24% (12/50) the deceased looked emaciated, in 20% (10/50) the deceased cried, in 4% (2/50) the deceased lived in a dark place, and in 4% (2/50) the deceased was in chains. These dreams were thought to indicate that the dreamer should perform rituals to help the deceased: if in the dream the deceased had poor clothes and looked hungry, then the dreamer should place food on the home altar and offer clothes and food to the monks at the temple through the gift-bestowal ritual (see Table 2). These dreams were said to be particularly common before Pheuchum Beun as a special plea of the deceased to the living to do the gift-bestowal to send needed items and merit.

“Soul-calling visitation.” These were the most feared dreams. In them, the deceased asked the dreamer's soul to accompany him or her. It is believed that if the dreamer does so, the dreamer's soul will not properly return to the body at the cessation of dreaming. This soul displacement is thought to cause severe illness or death. In the dreams of this type in our patient sample, the dreamer sometimes walked for some distance with the deceased before finding a way to escape. Often the dreamer told the relative that he or she had to return to the house to attend to some business or to care for children. It is thought that the deceased asks the dreamer to go with him or her because the deceased misses the dreamer greatly. Often the summoner was a parent and not uncommonly the dreamer considered him- or herself to be the favorite child.

Nostalgia dreams

These were 13% of all dreams of the deceased, and both of the subtypes involved seeing the deceased in some past setting that elicited a mood of nostalgia. It is believed that the deceased chose to have the relative see these scenes again so that the relative would realize that the deceased still has not been reborn and needed the relative to make merit for him or her. These dreams were of two types.

“Pre-Pol Pot daily scene.” The patient entered some bucolic scene that occurred during peaceful times before the Pol Pot period. In the most common type, the patient was joking around or eating in the old home with several relatives who are now deceased, a dream that was the reliving of a scene from childhood or young adulthood.

“Pol Pot daily scene.” The patient saw the dead relative in the Pol Pot period, often doing some chore like rice farming.

Trauma-reliving dreams

These were 25% of all dreams of the deceased, and were of two types, namely, either reliving or imagining an event concerning a certain person's death. It is believed that the deceased made the person dream of the trauma event in question to remind the dreamer that the deceased suffered a horrible death and still had not been reincarnated, and so to urge the dreamer to make merit for the deceased to help him or her achieve rebirth.

“Reliving an experienced trauma event.” The person relived an actual trauma event in which the relative or friend died. In a few of the cases, the trauma event was when the patient saw the relative or friend in question being killed or dying of starvation, and in some cases when the patient saw the relative or friend being taken from the home or workplace by the Khmer Rouge to be killed. The Khmer Rouge often arrested people at home and then took them to be killed at a nearby site. As indicated in the Introduction, the reasons for these killings were many: the person being considered to be lazy in work habits or suspected of being a former teacher, soldier, or policeman.

“Imagining an unwitnessed trauma event.” In the dream, the patient saw a death scene that was not actually observed in real life, and saw the scene either as imagined or as described by a third party. For example, though patients commonly witnessed relatives being taken away by a KR executioner, they more rarely witnessed the actual execution; but in the dream the patient saw the relative being killed, often being struck in the back of the head with a club, which was the most common means of execution in the Pol Pot period.

Cases of Bereavement that Feature Dreams of the Deceased

Below we give some case examples of how Cambodian patients experience and deal with grief following the death of their relative during Pol Pot and other time periods. All the cases are of patients who had dreams of the deceased and further illustrate how these dreams relate to bereavement processes and form a central part of the Cambodian bereavement ontology.

Case 1: Chea

This patient is a 51-year-old mother of five who saw her father die of starvation and illness in 1978 in the Pol Pot period. Her mother died about a year prior to the interview. The family did the usual funerary rites (see Table 1). In order to make further merit for her deceased mother, Chea cut off her hair “to show her gratitude” to her mother (sâng kun)xiii and asked some of her young male relatives to become monks for a few days. Nonetheless, five months after her mother's death, Chea had a dream in which her mother looked at her “sadly and quietly.” Then a few months later, just before Pheuchum Beun, Chea dreamed that her mother complained that she had neither clothes nor money, and that she was hungry because no one had offered her stew (semloo).xiv As a result of this last dream, Chea prepared a stew and put it on her home altar. She also did the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple in Lowell, giving food, twenty dollars, and clothes, asking during the ritual that her mother be “cool” (treujea treujum) and happy. When Chea called her sister in Cambodia to tell her of the dream, the sister gave clothes and money to the nuns at her local temple; the nuns bestowed blessings on Chea's mother as well as on Chea and her sister. Ever since Chea and her sister did these activities, Chea has not dreamed again of her mother.

Case 2: Chhway

This 52-year-old mother of seven children lost many relatives in the Pol Pot period. Chhway's father was a one-star general and her mother a teacher. Chhway was 17-years-old at the beginning of the Pol Pot period. One day when she went out of the house on an errand, the Khmer Rouge came and arrested her parents, her 13-year-old brother, and her two sisters ages 8 and 12. They were all certainly executed and pushed into a mass grave. Chhway and her husband fled far away with their two young children in the hope that her husband would not be identified as a former soldier; but a few months later he was recognized and they were all arrested. He was killed, and she was put in jail. When Chhway was finally let out of prison, she was so emaciated she could no longer nurse her 2-year-old daughter, who consequently died of starvation. Then during the chaos of the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, Chhway lost her 4-year-old daughter. Chhway went on to have five more children with two successive husbands, both of whom were abusive. Her fourth husband was very supportive and not physically abusive.

Chhway reported on her first clinic visit that she had dreamed her parents were hungry and asked her for their favorite fruit, the sapodilla (lemut). So the patient offered this fruit at the home altar and also presented it to the monks at the temple through the gift-bestowal ritual. In another dream prior to the clinic visit, a few days after the gift-bestowal ritual, Chhway saw her siblings with tattered clothes; the dream made her very concerned about their spiritual status.

About a week after this visit to the clinic, Chhway's husband died unexpectedly from an asthma attack. About six days after his death, he appeared to her in a dream, and he said she needed to eat more and so gave her some food. In fact, she had been not eating owing to depression and was quite thin. In the same time period, Chhway's daughter by another husband also saw Chhway's recently deceased husband in a dream. He was wearing very expensive clothes, including dapper “$10,000 shoes,” said he was living in Hollywood, and asked the daughter to be kind to her mother. This dream was interpreted by Chhway to mean her husband was probably about to be reborn. Chhway said that those persons who have very little demerit (baab) are reborn soon after cremation, or right after the 100-day ceremony, and that if one dreams of the deceased after 100 days that it suggests the person has demerit preventing rebirth.

Before the 100-day ceremony, Chhway dreamed her deceased husband said they would meet again and marry together after they were reborn, and that next time around he would be the older one, this reversal due to his having been reborn first. Chhway had another dream before the 100-day ceremony that she felt confirmed his rebirth. She dreamed that she went to the hospital to visit her husband and met another woman who also wished to see him. The doctor told both of them that Chhway's husband was on the 455th floor, a floor too high for them to reach.

Since the 100-day ceremony, Chhway has not dreamed of her husband, which she attributes to his being reborn. She says that if she saw him in a dream then it would mean he was still wandering the earth, literally, “spinning about” (wul wueul), because of demerit that was preventing rebirth. But she still continues to dream of her deceased parents and siblings at least once a month, which causes her great distress.

Case 3: Sarin

She is a 52-year-old mother of four. Up until 6 months ago, Sarin dreamed of her father multiple times a month for several months and in the dreams he always looked sad and did not talk to her. Consequently, about five months before her most current clinic visit, she performed at the temple the merit-making referred to as “recalling the soul of the deceased” (rumluk winyieunakhaan); the ceremony centers on doing the gift-bestowal ritual for the deceased. After that, Sarin dreamed of her father only once, which occurred the month previous to her current visit. In the dream, her father still looked sad. Upon awakening from the dream, Sarin had a flashback of the death of her uncle that occurred during the Khmer Rouge period, and this made her wonder how her father was killed. Her uncle was killed when the Khmer Rouge took over the city of Battambang, the provincial capital, and the Khmer Rouge arrested and executed those perceived to be enemies of the new regime. On the first day, they arrested her grandfather who had been in the Cambodian equivalent of the FBI and an uncle who had been a two-star general in the army. The next day the Khmer Rouge came to arrest another uncle at the house, even though he was not in the military, and Sarin witnessed the following: the Khmer Rouge shot her uncle in front of house, hitting him in the chest and the side of head, dislodging his eye. The next day they took her father.

Case 4: Bak

In the KR time, Bak ran away when the Vietnamese arrived to his village and he was able to reach the camps at the Thai border. His parents stayed behind in Cambodia and both soon died of starvation. For many years, he dreamed often of them and thought this meant they were not reborn. For this reason, in 1997 Bak and his siblings dug up the remains of the parents and cremated them. The ashes were put in an urn, which was placed in a stupa that was about ten feet high; then the gift-bestowal ritual was done at the stupa site. Afterwards Bak dreamed less frequently of his parents.

Thirteen years have elapsed since Bak performed these ceremonies, but Bak states that he still dreams of deceased relatives, including his parents, and that in recent years the dreams have been more frequent, particularly before the holidays. At this clinic visit, which happens to occur in the week before the Cambodian New Year, Bak recounts that in the previous month he dreamed of relatives three times. In one dream, he saw his brother who died of natural causes in 2005. The brother looked skinny, making Bak worry that the brother was in a difficult state and not reborn. In another dream, Bak was rice farming with his mother. In the third dream, his parents came and yelled at him. He thinks they wanted him to make merit for them and that they are not reborn.

A few days before the clinic visit, Bak asked a monk at the local temple about the meaning of his dreams about his parents. The monk said that Bak's parents were not born again and needed him to make merit for them to help erase their “demerit” (baab)—from past bad actions in the most recent or previous lives—so they might be reborn. Bak was planning to make merit for them through performing the gift-bestowal ritual at the Lowell temple and in the parents’ village in Cambodia where the stupa was located.

Case 5: Socheng

This 48-year-old mother of three lost her brother in 2003 from drowning. Seven days after his death, she dreamed her brother walked by her. At 100 days after his death, she dreamed her brother asked to stay with her, and she thought this meant he was not reborn. She did not have money to do the 100-day merit ceremony and she believed this might have impeded his rebirth. A year after his death, she dreamed her brother and several of his friends came to the house. In the following years, the brother repeatedly came in dream and asked her for things like rice and clothes. She would then do the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple to “send” these items to her brother. She thinks her brother is still hovering around, literally “whirling about” (wii wuel), and has not been reborn, so she is planning to perform a large merit-making that is referred to as “remembering the soul of the deceased” (rumluk winyieunneukhaan). She had arranged for two monks to chant accompanied by two female monks (yieuy jii) and one senior teacher (aacaa), The ceremony, which involves lengthy chanting, centers around doing the gift-bestowal ritual with many items like food, utensils, and clothing in order to make merit and send the items along with merit to the deceased.

Case 6: Bun

She is a 52-year-old mother of one. In 1976, when Bun was only 10-years-old, the Khmer Rouge came and arrested her father at their house. As she watched from a window with her mother, she saw her father beaten and then killed by a blow to the back of the head. His crime: he was a teacher. Her mother died soon thereafter of starvation.

Eight months ago at her clinic visit, Bun told of having frequent dreams of her relatives, particularly her father. In addition, when she did the “recalling-with-gratitude ritual” (nuk kun) and thought of her parents, she suddenly saw her father, and he was wearing old clothes and had a stomach pain (on nuk kun, see Table 2). As she described this, she was tearful. A few days after the clinic visit, she consulted with a monk, who told her to donate medicine and food through the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple. He also told her to do the recalling-with-gratitude ritual more often and for a longer period of time.

As the monk suggested, Bun made an offering of food and clothes at temple through the gift-bestowal ritual, and started doing the recalling-with-gratitude ritual three times a week for about 5 minutes. She called this a form of concentration meditation (samathi) because it involves conjuring to mind the image of the Buddha and then one's parents and their good acts. After doing the gift-bestowal ritual and the recalling-with-gratitude ritual for several months, Bun started seeing her father every few months in a dream. He had new clothes, but he was still skinny and often complained of pain in his neck (presumably because he was killed by a blow there) and stomachache.

At her most current visit, which takes place about eight months after the visit described above, Bun recounts that she is dreaming of family members about 3 times a month. She describes three types of dreams. In one dream that has recurred in previous months, her mother comes and asks her to go with her, which greatly frightens Bun. In another recurrent dream, Bun sees her mother when she was very ill and dying of starvation. In another dream this month, which was not recurrent, her father was caring for her mother.

One of Bun's nephew claims to be a reincarnation of her father. But Bun doubts this to be the case because she still dreams of her father, which indicates he is not reborn. When Bun is ill, she often dreams that her mother, dressed all in white, comes to comfort her. If Bun dreams of her father or mother, she does the gift-bestowal ritual for them.

Case 7: Chea

Chea is a 58-year-old mother of five. Both of Chea's parents died in the Khmer Rouge period. In 1975, when she was only twelve years old, she saw her father and mother arrested at the house and taken away, with their arms tied behind their backs. They were arrested because the father was a former soldier. She heard from others that they were tortured before being killed. To this day, around the Cambodian New Year or around Pheuchum Beun, she usually dreams of her mother. Often her mother asks for a favorite food like watermelon, and she usually is dressed poorly. Chea feels sad upon awakening from such dreams and soon afterwards goes to the temple to offer food in the gift-bestowal ritual. She explains that after death people live in a purgatory of sorts, and that if they are suffering in some way, such as starving, then they will go to their children and apprise them of this fact so that the children will make merit for them. Each evening Chea lights incense, bows to the Buddha, and asks for protection from the Buddha and relatives.

Case 8: Chherng

This patient did not go to the Pheuchum Beun this past year because she had no money to offer the monks or to buy food offerings with: she used her last few dollars for the month on laundry. Nor did Chherng offer (saen) any food at the home altar. A few days later, which was a just before her clinic visit, she had a dream. Her father came and asked, “Why did you not send me any food? Why did you not light incense and offer food at the altar for me?” In the dream, she replied, “I have no money.” Chherng noticed that he had poor clothes, and she asked him why. He said he had no other clothes, only his old garb in shreds. Chherng promised her father that she would offer clothes at the temple to the monks in the gift-bestowal ritual.

Case 9: Chhoum

In 1975, when Chhoum was 20 years old, the Khmer Rouge came to his parent's home at seven in the evening and arrested Chhoum along with his parents and his four siblings, and took them to be killed. Along the way, they hit his father with a club and asked about his past army history. The father had been a soldier until 1970, quitting many years before Pol Pot took over in 1975, but he was still targeted for execution, and so too were his whole family because they were considered to be “polluted” owing to his military involvement.

When they arrived at the execution spot, he and his family members were each blindfolded with a scarf. They tortured and interrogated Chhoum's father for another hour, and Chhoum could hear the blows and screams. They then took Chhoum along with his father, mother, and siblings for execution. They hit each of them in the back of the neck at the base of the skull with a club. When Chhoum awoke, he was in a pit with two bodies on top of him. The person above him was alive, and they were able to turn back-to-back and untie one another. Chhoum and the other man crawled out of the pit. They saw no other survivors and were too frightened to delay departure, so they fled away to a distant village.

Over 30 years later, Chhoum often still sees in his dreams his father being beaten at the execution spot despite the fact that he himself had been blindfolded at that time. Sometimes he dreams of his father being sent to work during the Pol Pot period. A monk told him that he sees these things because his father misses him and thinks about him and so causes him to have these dreams. The monk suggested he make merit and send it to the father. Chhoum makes merit at the temple once every two weeks by doing the gift-bestowal ritual and then goes home and lights incense and tells his father of having made merit and prays that his father be reborn.

Case 10: Vann

Every month in a dream Vann sees his brothers executed. The Khmer Rouge forced the patient to watch as they killed and then eviscerated the brothers, who had been soldiers.

Case 11: Kean

Every month in a dream Kean sees the corpse of younger sister who died of starvation in the Pol Pot period. He witnessed the death.

Case 12: Ea

Ea is a 55-year-old mother of five. Her family was targeted for severe treatment by the Khmer Rouge because her family was part Chinese, even though all of them were fluent Khmer speakers. Her father died of starvation in 1976, and her mother was arrested and taken away and killed, and three of her five siblings were killed by the Khmer Rouge. She didn't witness any of these events but heard about them from others. But in the month prior to her most recent visit, Ea dreamed of her mother being taken away to be killed. Ea thinks her mother is making her see this past trauma and that her mother is not reborn and misses her.

Case 13: Hong

Hong and her husband both presented to the clinic with extremely severe PTSD. Both Hong and her husband had survived execution. In different incidents, separated by several months, the Khmer Rouge had hit each of them with a club in the back of the head and left them for dead, but both had survived. Hong's father had died in 1968, several years before the Khmer Rouge period, and two of her brother's had died in the Pol Pot period. One brother stole food when starving and was caught and so was killed; another brother disappeared.

At her first clinic visit, Hong recounted that her mother, with whom she lived, had died just 10 days before; Hong cried throughout the visit and was almost inconsolable. Hong said that in the seven days following her mother's death, and before her cremation, the family had done the gift-bestowal ritual at the temple as was the custom (Table 1). Each time while performing the gift-bestowal ritual, the monk had uttered the usual entreaty, asking that the mother be born and not “hang around her children”; as per custom (see Table 2), the monk had an assistant burn a paper on which had been written the mother's name. The monk also had them light a candle and incense at the home altar and spray perfume on the altar's Buddha image, and ask that the mother be reborn to a high state. Also, before the cremation (bueh muk pleung), two of Hong's grandchildren had become monks for several days. Hong said that those who have died “circle about” (wii wuel) until the merit ceremony at 100 days, when they usually are reborn. Hong said she wanted to see her mother in a dream. (As indicated above, in the first 100 days, dreaming about the deceased is considered normal and is not usually considered dangerous, and often living relatives want to see the deceased in this time period.) Hong said maybe her mother no longer thought of her and so had not come to visit her. At this same visit, Hong's husband reported he had twice dreamed of his mother-in-law. In one dream that he had a few days before his mother-in-law died, he dreamed that three women dressed in white said they had come for his mother-in-law; he asked them not to take her, but they said they would take her anyway. After his mother-in-law died, he saw her in a dream and she had tattered and dirtied clothes. So Hong and her husband were thinking of doing the gift-bestowal ritual of special clothes at the temple for Hong's mother.

At the next clinic visit one week later, Hong said she saw her mother in a dream and she had no proper clothes (geunsaeng), that they were tattered and dirtied. Hong her dreams and those of her husband indicated the need to do gift-bestowal ritual of clothes at the temple, and they had done so; afterwards, she dreamed of her mother and her mother had nice clothes (geunsaeng). Hong also had offered food on the home altar, lighting incense and candles. She said that some people claim that the dead can only smell the food if it is presented at the home altar, but that others say you need to donate objects and food to monks through the gift-bestowal ritual to have donations arrive to the dead. At this same clinic visit, Hong also related that her mother had paid for the construction of a stupa next to a temple in Cambodia, intending that her urn would be placed there. Hong doesn't know when she will be able to take the urn to Cambodia because of the cost of airfare, of the formal merit-making ceremony, and of distributing money and other objects in alms to the poor to make further merit. Hong felt guilty about not yet having been able to do this.

At the subsequent visit two months later, Hong reported having dreams several times a month in which her mother called her to come with her. These dreams terrified her; as she talked of them, she looked very frightened and said that just thinking of the dreams caused her heart to beat fast and her hands and feet to go cold. As a result of the dreams, she started placing bananas and other offerings at the home Buddha altar and then did three devotional prostrations—a kowtow-like motion but with the hands kept in a lotus form in front of the face—to ask for protection from the Buddha and asked for her mother to be reborn. Also, each day, she started placing food on a table in her mother's old room and next to it lit incense; then she raised her hands in front of her face, clasped together in a prayer-like gesture, and said to her mother, “Mom, go to be reborn, do not miss your children so much.” At this same visit, she also mentioned starting to have dreams of her father, who died in 1970 before the Pol Pot period, asking her to come with him, and this caused her to awake in panic. She also dreamed her father came and took her mother to Cambodia.

Then two weeks later, Hong dreamed again that her father asked her to go with him, saying he lived alone. He was dressed in white, which she said meant he was in a sad state (gan tuk). The patient begged him to let her stay, telling him she had grandchildren. As a result of these dreams, she had started to light incense to her father every night; at that time, and others, she entreated her father to be reborn and leave behind his relatives (reuwii reuwul). She said her father was a farmer and killed many animals and that this might be why he had not been reborn. It also happened that a cousin of Hong's husband died the previous month, and the husband dreamed that the cousin asked him to go with him. He was very frightened by the dream. Thus, Hong and her husband were very distressed at the appointment.

Now a few months later, Hong and her husband are much better. Though she continues to dream of her mother about twice a month, the dreams are less frightening and even comforting. In one dream, her mother asked her to keep making merit. In that dream, her mother was wearing black pants and a blouse with flowers, clothes that Hong had given her by donating them to the temple in a merit-making ceremony. (On two occasions she donated this type of clothing to the temple because they were her mother's favorite.) In another dream, her mother didn't say anything initially, then called out to her, and next disappeared. Hong cried on awaking. Whenever Hong dreams of her mother, she goes to the temple, and takes a stew, clothes, money, towel, incense, and candles, to do the gift-bestowal ritual. Reflecting back on her dreams, Hong notes with relief her mother's changing appearance. Initially her mother wore tattered and dirty clothes; then she wore white, which indicated having attained a better merit status but still being in a sad statexv; and then she had a flower blouse and black pants. Hong also notes that she has seen her mother wear other items she donated to her at the temple, including a jacket.

Case 14: Huy

One day back in 1976, the Khmer Rouge arrived to Huy's house, and all her family members, including two grandparents, were taken to be killed because of her family's supposed Chinese ancestry—her father was Chinese and spoke Cambodian poorly whereas her mother had no Chinese ancestry—and the accusation that they had been wealthy, when in fact they were poor: the father made furniture. Huy had gone out to run an errand and so was not taken to be killed. Upon Huy's return, a woman she knew told her about her family's fate, and where they were taken to be killed. Huy asked to be taken there. They got to about 50 yards from the killing area and hid in the jungle cover. From there they could see a pit next to which there were hundreds waiting to be killed, presumably including her family members. Four Khmer Rouge were equally spaced around a pit, and behind each Khmer Rouge was a line of people, each of whom was squatting down with the arms tied behind the back; the front person in line was killed in the following fashion. Older children and adults were told to kneel and bend their necks over, and then the Khmer Rouge hit the back of their necks with the stock of a gun or the blade of a machete and pushed their limp or convulsing bodies into the pit; babies were grabbed by their feet and swung head first into trees, the bodies then thrown into the pit. After a short while, Huy saw her family members squatting in a line behind one of the Khmer Rouge. Huy started to cry out and about to run over to them when the woman covered her mouth, and Huy fainted. A few days later, Huy was arrested and tortured, suspected of being another member of the family.

At an appointment six months before her most recent appointment, Huy said she dreamed of her mother about once every two months, and often dreamed of her other murdered family members as well. In one type of dream that Huy had every two months, she saw her mother, father, and all her dead siblings. In the dream, the family members were skinny and wearing dirty clothing as they were during the Pol Pot period. Huy called out to her family members, but they didn't reply or react, acting as if they could not hear her; at other times, her siblings called out to her for help. In another type of dream that Huy had every month or two, she saw her father, mother, and siblings being killed. In the dream, her father was hit in the back of head; her mother was struck with a machete at the neck; and her siblings were shot. At other times, her mother would come and tell her how she was killed. (In fact, Huy had not witnessed any family member actually being killed, as was described above.) Huy said that her parents told her and showed her in dream how they died so Huy would keep making merit for them.