Abstract

PURPOSE

Awareness of and enrollment into outpatient cardiac rehabilitation (OCR) following a cardiac event or procedure remains suboptimal. Thus, it is important to identify new approaches to improve these outcomes. The objectives of this study were to identify: (1) the contributions of a patient navigation (PN) intervention and other patient characteristics on OCR awareness; and (2) the contributions of OCR awareness and other patient characteristics on OCR enrollment among eligible cardiac patients up to 12 weeks post-hospitalization.

METHODS

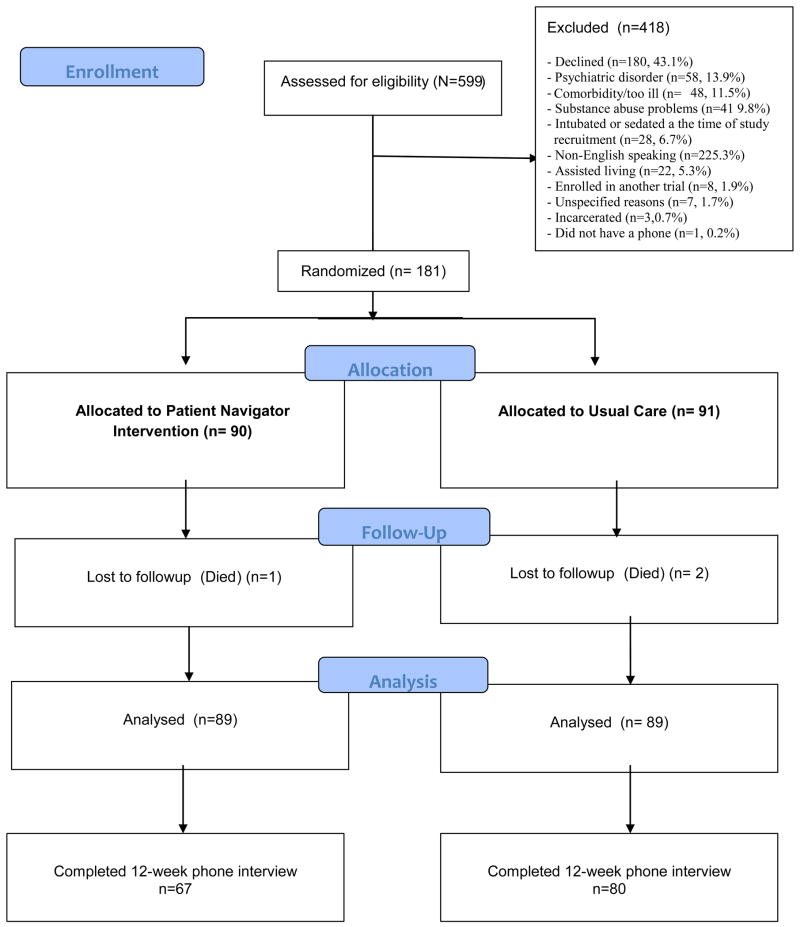

In this randomized controlled study, 181 eligible and consenting patients were assigned to either PN (n=90) or Usual Care (UC; n=91) prior to hospital discharge. Awareness of OCR was assessed by telephone interview at 12-weeks posthospitalization and OCR enrollment was confirmed by staff at collaborating OCR programs. Of the 181 study participants, 3 died within 1 month of hospital discharge, and 147 completed the 12-week telephone interview.

RESULTS

Participants in the PN intervention arm were nearly 6 times more likely to have at least some awareness of OCR compared to UC participants (OR=5.99; P=.001). Moreover, participants who reported at least some OCR awareness were more than 9 times more likely to enroll in OCR (OR=9.27, P=.034), and participants who were married were less likely to enroll (P=.031).

CONCLUSIONS

Lay health advisors have potential to improve cardiac patient awareness of outpatient rehabilitation services, which in turn can yield greater enrollment rates into a program.

Keywords: awareness, cardiac rehabilitation, cardiovascular diseases, patient participation

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality world-wide.1 Outpatient cardiac rehabilitation (OCR) is an evidence-based approach to effectively reduce the burden of CVD and improve quality of life among survivors of a cardiac event/procedure.2–4 Yet, referral to and enrollment in OCR is low.5,6 The largest and most comprehensive U.S.-based study of OCR utilization to date reported an average participation rate of 18.7%.6 This is disconcerting given that OCR services are recommended as a Class I, Level A standard guideline in clinical practice after a cardiac event.2,5,7

The primary focus of interventions to improve OCR enrollment has been inpatient physician referral behavior using automated referral methods such as prompts, flagging, or standing discharge order sets.8–13 These methods have demonstrated improvements in referral but weak effects on actual OCR enrollment. One problem is that patients may be unaware of OCR, and not adequately informed about OCR at the time of hospital discharge and/or during postdischarge followup care.

This study tested a novel patient navigation (PN) approach to improve transitions in care between an academic medical center inpatient cardiac services and OCR programs located near the tertiary care center. Patient navigators are lay individuals who assist patients through the healthcare system to improve access and improve the understanding of their health. Consistent with the literature on patient navigation,14–16 the investigators implemented a PN program to compare it to usual care (UC).

Although the authors previously demonstrated that a cardiac PN intervention resulted in higher rates of OCR enrollment compared to UC,17 the analyses reported herein examined the contribution of factors other than intervention group assignment that may effect OCR enrollment,6,18 including OCR awareness and patient characteristics (clinical, sociodemographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors). The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that PN patients would have higher OCR awareness compared to UC patients, and patients who were more aware of OCR would be more likely to enroll in an OCR program. Thus, the current study identified: (1) the contributions of the PN intervention and patient characteristics on OCR awareness; and (2) the contributions of OCR awareness and patient characteristics on OCR enrollment.

METHODS

The study design was a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Details of the study have been published elsewhere.17 In brief, participants were recruited during a hospital admission at Stony Brook University Hospital (SBUH), Long Island, New York. Ethics approval for the study protocol was received by the Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects at SBU. Figure 1 presents the study flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Study FlowDiagram

Patients

From May 2009 to June 2011, 599 patients were screened on the general cardiology and thoracic surgery floors. Inclusion criteria were: age 21 years or older and a diagnosis clinically indicated for OCR referral [myocardial infarction (MI), stable heart failure (HF) and patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) or heart valve surgery].2,5,7 Exclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1.

Intervention Description

Two navigators were trained to provide basic education and support (informational, social) about OCR while visiting consenting patients at the hospital bedside, by phone (approximately 1 week after hospitalization), and via mail. Trainings were conducted by the investigators and included materials adapted from a PN cancer training tool kit19 and a manual designed for community health workers on CVD.20 The role of the PN was to educate and activate patients to effectively navigate the inpatient to outpatient cardiac care system, with a particular focus on enrolling in a local OCR program of patient choosing. The PN group had a navigator meet them briefly prior to discharge. Patients were given information about OCR (ie, the likely benefits of participation, the location of local programs and details on how to access it) and their navigator facilitated enrollment into a program. PN patients discharged prior to receiving navigation (n=25) were mailed the same information to their home which was reviewed by telephone with a navigator within 1 week. Approximately 10 days after hospital discharge, patients randomized to PN received a followup telephone call to encourage them to discuss OCR with a physician (primary care, internist, or cardiologist) and to encourage enrollment into the program. Navigators provided additional calls as needed to talk with patients about any barriers to enrollment in OCR they encountered.

Usual Care

Those individuals not assigned to the PN group received standard discharge instructions provided to all patients. Physician referral to OCR prior to discharge, telephone-based support postdischarge to encourage OCR enrollment and mailed information about OCR are not standard practice at SBUH.

Measures

Sociodemographic, clinical, and health system data were extracted from inpatient and outpatient medical charts and assessed by self-report during 2 indepth telephone interviews 4 and 12 weeks posthospitalization. Interviews were conducted by research staff using psychometrically-validated scales and study-specific measures. Demographic data collected from the hospital charts included: age, gender, and marital status. Self-reported race, family income and work status were assessed at the time of the first telephone interview. These variables were dichotomized as follows: marital status (married: yes/no), education level (more than a high school education: yes/no), race (white: yes/no), family income (≥$50,000 US dollars: yes/no), work status (working full/part-time: yes/no).

Clinical variables abstracted from inpatient medical charts included: index cardiac diagnosis/procedure (MI, PCI, CABG, stable angina, HF, and valve surgery), the presence of CVD risk factors (smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes) and body mass index (BMI).

Comorbidities were assessed using the Charleson Comorbidity Index during the first telephone interview.21 Depression was measured at baseline and follow-up telephone interviews using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).22

Relevant health system data abstracted from inpatient charts included: insurance (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid or self-pay), completion of inpatient physical therapy/CR (yes/no) and length of hospital stay (days).

At the time of the 12-week phone call structured interview, the participants were provided with a description of OCR. Thereafter a subsequent question about OCR was directed to all participants: “Which statement best describes what you knew about a monitored exercise program called outpatient cardiac rehabilitation prior to this call?” The responses were coded as (1) I had no information about it; (2) I had some information about it; (3) I feel my knowledge is very complete. This variable was dichotomized for the logistic regression analysis and coded as: (1) I had at least some information about OCR and (2) I had no information about OCR.

OCR enrollment was defined as having attended at least 1 OCR session (beyond that of the initial intake assessment). OCR enrollment data were initially collected by telephone during the postdischarge interview conducted 12 weeks following discharge from the index hospitalization. For patients who reported participating in an OCR program, the staff of the program was contacted by the research team to verify enrollment. For those patients who did not complete the second telephone interview (n=9 UC and n=22 PN), the research staff contacted the OCR directors at each of the known programs located in Suffolk County to determine enrollment status.

Interviews

The indepth interviews were conducted by a group of survey researchers located at the Center for Survey Research (CSR) at Stony Brook University who worked independent of the authors/investigative team, and they were not aware of patient assignment while conducting the interviews. The CSR uses state-of-the-art hardware and software for sample management, questionnaire programming, and the data collection process. For sample management and questionnaire programming, the CSR utilizes WinCati, the Windows Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing System (Sawtooth Technologies, IL USA). With the CATI system, each question appears on a computer monitor for the interviewer to read. Interviewers had no control over questionnaire branching, and response options were read verbatim. All patients, regardless of group assignment, were given an identical brief explanation about cardiac rehabilitation (during the Time 2 phone interview); trained interviewers read the exact same text to each patient in the study, as it appeared on their computer monitor, while conducting the phone interview and recording responses in real time.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate tests of demographic, clinical and health system variables were undertaken to examine differences in characteristics between intervention groups (PN vs. UC), and those participants who completed the 12-week telephone interview compared to those who were lost to followup. Two-tailed Fisher’s Exact Tests were used for categorical variables and independent sample t-tests were used for continuous variables.

To address the first objective, a backwards stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the contribution of predictors to OCR awareness. The starting variables were: group intervention assignment (PN vs. UC), age, gender, race, marital status, education, insurance status, HF, MI, CABG, PCI, depression (CES-D) and smoking status.

For the second objective, a backwards stepwise logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the contribution of OCR awareness and other predictors to OCR enrollment. The group assignment variable was not included in the model as it is strongly associated with OCR awareness (χ2=14.2, df =1, P<.001). Additionally, family income was not included in the model due to excessive missing data (21.3%). The starting variables were: OCR awareness, gender, age, education, race, insurance status; CABG, PCI, MI, depression and smoking status). These variables were selected for inclusion in the models as they were significant in the univariate analyses and/or have been commonly reported barriers to OCR enrollment.6,18 Statistical significance was P<.05 for all analyses. SPSS Version 20.0 was used for all analyses (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL USA).

RESULTS

Of the 599 inpatients screened for the trial, 181 were considered eligible and consented to participate in the study (418 were excluded). Reasons for study exclusion are presented in Figure 1. Of the 181 trial participants, 3 died prior to the time of the first telephone interview (within 1 month of hospital discharge) and therefore were excluded from the analyses. Two of these patients were assigned to the UC group and 1 was in the PN intervention group.

Table 1 shows the demographic, clinical, and health system variables at baseline. Overall, participants were primarily male, white, married, had an education greater than high school, had an MI and high cholesterol, were hypertensive and had insurance coverage. The mean age was 60.4 years (age range: 26–83) with 63 (35.4%) participants aged 65 or older. PN participants were less likely to be married and had a higher education compared to UC participants.

Table 1.

Patient Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=89) | Usual Care (n=89) | Total (n=178) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 60.2 (9.9) | 60.7 (11.1) | 60.4 (10.5) | .76 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 32 (36.0) | 28 (31.5) | 60 (33.7) | .63 |

| White ethnocultural background, n (%) | 64 (87.7) | 71 (85.5) | 135 (86.5) | .82 |

| Married, n (%) | 48 (53.9) | 63 (70.8) | 107 (60.1) | .03 |

| Education level (more than high school), n (%) | 50 (68.5) | 44 (53.0) | 93 (60.3) | .05 |

| Income (less than $50,000 USD), n (%) | 37 (50.0) | 37 (50.0) | 70 (50.0) | 1.00 |

| Working full/part time, n (%) | 23 (31.9) | 34 (42.0) | 37 (37.3) | .24 |

| Clinical | ||||

| Index diagnosis/procedureb, n (%) | ||||

| MI | 75 (84.3) | 73 (82.0) | 148 (83.1) | .84 |

| PCI | 66 (74.2) | 59 (66.3) | 125 (70.2) | .33 |

| CABG | 15 (16.9) | 15 (16.9) | 30 (16.9) | 1.00 |

| Multivessel CABG, n (%) | 14 (93.3) | 13 (86.7) | 27 (90.0) | 1.00 |

| Heart failure | 12 (13.5) | 23 (25.8) | 35 (19.7) | .06 |

| Heart valve surgery | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes, Type 2, n (%) | 29 (32.6) | 28 (31.5) | 57 (32.0) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 70 (78.7) | 72 (80.9) | 142 (79.8) | .85 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 64 (71.9) | 53 (59.6) | 117 (65.7) | .11 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.8 (6.3) | 31.6 (6.8) | 31.1 (6.6) | .43 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 27 (30.3) | 18 (20.2) | 45 (25.3) | .17 |

| LVEF < 40%, n (%) | 13 (22.0) | 17 (27.0) | 30 (24.6) | .54 |

| Number of comorbidities present (Charlson Index), mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.58) | 2.7 (1.8) | 2.62 (1.7) | .65 |

| Depressive symptoms, mean (SD) | 8.2 (10.1) | 8.9 (10.1) | 8.6 (10.1) | .66 |

| Health System | ||||

| Completed inpatient PT/CR, n (%) | 20 (22.5) | 24 (27.0) | 44 (24.7) | .60 |

| Medical insurance coveragec, n (%) | 72 (80.9) | 78 (87.6) | 150 (84.3) | .30 |

| Medicared | 11 12.4) | 9 (10.1) | 20 (11.2) | - |

| Medicaidd | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | - |

| Commerciald | 35 (39.3) | 41 (46.1) | 76 (42.7) | - |

| Commercial + Medicared | 18 (12.4) | 20 (22.5) | 38 (21.3) | - |

| Commercial + Medicaidd | 2 (2.2) | 6 (6.7) | 8 (4.5) | - |

| Medicare + Medicaidd | 4 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.2) | - |

| Self-pay (not insured)d | 17 (19.1) | 11 (12.4) | 28 (15.7) | |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD) | 5.2 (4.8) | 5.4 (4.5) | 5.3 (4.6) | .79 |

P-values test for differences between the Patient Navigator (Intervention) group and the Usual Care group

Cardiac event/procedures may not be mutually exclusive

Variable dichotomized as “insured” versus “not insured (self-pay)” at the time of hospitalization

Data are presented only for the total sample for descriptive purposes

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; USD, United States dollars

Baseline Patient Characteristics Between Telephone-Interview Completers and Noncompleters

Table 2 presents the differences in baseline patient characteristics between retained (n=147) participants versus those lost to followup at the 12-week telephone call (n=31). As shown, the participants that were retained were more likely to have medical insurance coverage compared to those not retained (P=.05). Not having diabetes (P=.094) approached statistical significance towards being more likely to be retained at the 12-week followup. When these data were split by group intervention assignment (PN and UC), there were no sociodemographic, clinical, or health system differences between those retained and lost to followup. However among UC participants, having had a PCI (P=.056) and medical insurance (P=.079) approached statistical significance among those retained compared to nonretained participants.

Table 2.

Differences in Baseline Patient Characteristics Between Retained and Not Retained Participants

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=89) | Usual Care (n=89) | Total | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Retained (n=67) | Not Retained (n=22) | Retained (n=80) | Not Retained (n=9) | Retained (n=147) | Not Retained (n=31) | ||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 60.3 (11.0) | 59.8 (6.0) | 60.6 (11.1) | 61.4 (11.3) | 60.5 (11.0) | 60.3 (7.8) | .91 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 21 (31.3) | 11 (50.0) | 25 (31.2) | 3 (33.3) | 46 (31.3) | 14 (45.2) | .15 |

| White ethnocultural background, n (%) | 59 (88.1) | 5 (83.3) | 89 (86.2) | 2 (66.7) | 128 (87.1) | 7 (77.8) | .35 |

| Married, n (%) | 36 (53.7) | 12 (54.5) | 58 (72.5) | 5 (55.6) | 94 (63.9) | 17 (54.8) | .42 |

| Education level (more than high school), n (%) | 48 (71.6) | 2 (33.3) | 43 (53.8) | 1 (33.3) | 91 (61.9) | 3 (33.3) | .16 |

| Working full/part time, n (%) | 20 (30.3) | 3 (50.0) | 32 (41.0) | 2 (66.7) | 52 (36.1) | 5 (55.6) | .29 |

| Clinical | |||||||

| Index cardiac condition/procedure, n (%) | |||||||

| MI | 56 (83.6) | 19 (86.4) | 65 (81.2) | 8 (88.9) | 121 (82.3) | 27 (87.1) | .61 |

| PCI | 50 (74.6) | 16 (72.7) | 56 (70.0)$ | 3 (33.3) | 106 (72.1) | 19 (61.3) | .28 |

| CABG | 12 (17.9) | 3 (13.6) | 13 (16.2) | 2 (22.2) | 25 (17.0) | 5 (16.1) | 1.00 |

| Heart Failure | 10 (14.9) | 2 (9.1) | 19 (23.8) | 4 (44.4) | 29 (19.7) | 6 (19.4) | 1.00 |

| Heart valve surgery | 1 (1.5) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (3.2) | .44 |

| Diabetes, Type 2, n (%) | 19 (28.4) | 10 (45.5) | 24 (30.0) | 4 (44.4) | 43 (29.3) | 14 (45.2) | .09 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 51 (71.6) | 19 (86.4) | 66 (82.5) | 6 (66.7) | 117 (79.6) | 25 (80.6) | 1.00 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 49 (73.1) | 15 (68.2) | 48 (60.0) | 6 (55.6) | 97 (66.0) | 20 (64.5) | 1.00 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.7 (6.3) | 31.1 (6.2) | 31.4 (6.4) | 33.2 (10.1) | 31.1 (6.4) | 31.7 (7.4) | .64 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 18 (26.9) | 9 (40.9) | 17 (21.2) | 1 (1.2) | 35 (23.8) | 10 (32.2) | .37 |

| Number of comorbidities present (Charlson Index), mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.5) | 3.1 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.7) | .24 |

| Depressive symptoms, mean (SD) | 8.0 (9.8) | 11.0 (14.0) | 9.1 (10.2) | 5.3 (5.0) | 8.6 (10.0) | 9.1 (11.7) | .88 |

| Health System | |||||||

| Completed inpatient PT/CR, n (%) | 17 (25.4) | 3 (13.6) | 20 (25.0) | 4 (44.4) | 37 (25.2) | 7 (22.6) | 1.00 |

| Medical insurance coverage, n (%) | 56 (83.6) | 16 (72.7) | 72 (90.0)a | 6 (66.7) | 128 (87.1) | 22 (71.0) | .05 |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD) | 4.8 (3.6) | 6.6 (7.3) | 5.3 (4.5) | 6.6 (4.2) | 5.1 (4.1) | 6.6 (6.5) | .09 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PT/CR, Physical Therapy / Cardiac Rehabilitation

OCR Awareness, Enrollment and Intervention Effects

One hundred and forty-seven participants completed the 12-week telephone call (82.6%). Sixty-seven PN and 80 UC participants answered the question: “Which statement best describes what you knew about a monitored exercise program called outpatient cardiac rehabilitation prior to this call?” The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Self-reported OCR Awareness Among PN and UC Participantsa (n=147)

| No OCR awareness | At least some OCR awareness | Knowledge of OCR is complete | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n=147) | 35 (23.8%) | 49 (33.3%) | 63 (42.9%) |

| PN group, n= 67 | 6 (9.0%) | 24 (35.8%) | 37 (55.2%) |

| UC group, n= 80 | 29 (36.2%) | 25 (31.2%) | 26 (32.5%) |

χ2=16.0, P<.001.

Abbreviations: OCR, outpatient cardiac rehabilitation; PN, patient navigation; UC, usual care

The logistic regression model for OCR awareness is presented in Table 4. The results show that participants in the PN intervention group were nearly 6 times more likely to have at least some awareness of OCR compared to the UC group participants. Additionally, participants who were younger, had higher education, did not have HF or did not undergo a PCI procedure or CABG surgery were more likely to have at least some OCR knowledge.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Model Examining Predictors of OCR Awarenessa

| Variable | Wald χ2 | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| PN group assignment | 10.94 | 5.99 | 2.07 | 17.30 | .001 |

| Younger ageb | 5.10 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.99 | .024 |

| Greater educationc | 3.92 | 2.49 | 1.01 | 6.13 | .048 |

| CABG surgery | 5.35 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.76 | .021 |

| PCI procedure | 3.98 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.98 | .046 |

| Heart failure | 4.95 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.86 | .026 |

Variables included in the Backwards Stepwise model: Intervention group, marital status, heart failure, gender, age, race, education, insurance status; CABG, PCI, MI, depression, and smoking status.

For each additional year of age, the likelihood of awareness drops by approximately 5%

Greater education pertains to having more than a high school education

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PN, patient navigation

As previously reported,17 of the 178 study participants, 27 (15.2%) enrolled in an OCR program. Participants enrolled into 1 of 6 programs (2 private clinics and 4 hospital-based CR programs). Group comparisons revealed that 21 of the 89 PN participants (23.6%) and 6 of the 89 UC participants (6.7%) enrolled in an OCR program (P=.003 in Fisher’s Exact Test).

The logistic regression model for OCR enrollment is presented in Table 5. The results show that participants who reported at least some OCR awareness were more than 9 times more likely to enroll in OCR and participants who were married were less likely to enroll in the program.

Table 5.

Backwards Stepwise Logistic Regression Model Examining Predictors of OCR Enrollmenta

| Variable | Wald χ2 | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Greater OCR awareness | 4.51 | 9.27 | 1.19 | 72.31 | .034 |

| Married | 4.65 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.91 | .031 |

Variables included in the Backwards Stepwise model: OCR awareness, marital status, heart failure, gender, age, race, education, insurance status; CABG, PCI, MI, depression, and smoking status.

Abbreviations: OCR, outpatient cardiac rehabilitation; OR, odds ratio; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MI, myocardial infarction;

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first RCT to test the effect of a PN intervention on OCR awareness and subsequent enrollment into OCR. Among the participants who completed the 12-week follow-up interview, navigated patients were nearly 6 times more likely to be aware of OCR relative to patients provided usual care. Additionally, patients who reported having at least some or complete knowledge of OCR were more than 9 times more likely to enroll in OCR relative to patients with no knowledge of OCR at the 12-week interview.

The results from this study have shown that a PN intervention can be successful in improving cardiac patient awareness about OCR and result in greater program enrollment rates. Few research studies have examined the effect of awareness on OCR enrollment; however, some studies have reported it to be an important variable in program enrollment23,24 Prior studies have reported that most eligible cardiac patients are uninformed about OCR, what it is, how to access local programs, the potential benefits, and how it relates to their overall recovery.23–29 Additionally, other patient characteristics that were found to be associated with lower OCR awareness (older age, lower education, heart failure, and having had a PCI or CABG) warrants further investigation.

The fact that this study found that PCI and CABG patients reportedly were less knowledgeable about OCR is especially disconcerting, as clinical practice guidelines indicate these patients are to be automatically referred.7 Interventions may be especially needed to targeted PCI and CABG patients to improve their awareness of OCR.

Although this intervention study has shown promise, more research is certainly warranted. In the U.S., the largest and most comprehensive quality improvement initiative that includes OCR targets is the GWTG program.30 This initiative has shown significant improvements in OCR referral;8,31,32 however, only 1 GWTG pathway analysis has reported on OCR enrollment rates.10 In this study, a single center followed the GWTG program for a period of 18 months among patients with MI (N=780). The results showed that the GWTG pathway did not result in significantly greater enrollment rates compared to the nonpathway group (19% vs. 6%, respectively), although a trend was noted (P=.08).10 In comparison to the Mazzini study, our sample demonstrated a higher (modestly) OCR enrollment rate (24%) compared to usual care. This may suggest that interventions specifically designed to target OCR enrollment using both inpatient and postdischarge contact with a lay advisor would be an added benefit to the GWTG program or other inpatient strategies to improve transitions in care targeting OCR participation.

Implications

The success of interventions to increase utilization of OCR programs has several implications. Chiefly, OCR programs might not have sufficient staff or funding to handle dramatic increases in patient volumes, which may increase wait times for patients to access OCR. Such delays could result in deterioration in the patient’s medical and psychological health33 and pose as a major barrier to program attendance.34,35 Therefore, increasing funds for additional staff or larger facilities would be imperative to meet additional capacity needs. Alternatively, referral to homebased OCR, which has been shown to be as equally effective as structured OCR programs36 and more accessible or preferable as a low-cost alternative37 should be considered.

Although increasing OCR use is important, enrollment benchmarks in the U.S. have not been described by panel experts as they have in other countries such as Canada38 and the U.K.39 It is currently unknown what rate would be feasible in the U.S. Moreover, there are several health-system factors which impede OCR enrollment. These include lack of insurance coverage, poor coordination of securing referrals while in hospital or postdischarge, large variation between regions and lack of a relationship between hospitalists and community physicians and OCR program staff.40 In the current study, not 1 OCR referral was noted in the inpatient charts for all of the study participants prior to hospital discharge (data not described). Automated referrals to OCR (such as standard order set on the discharge summary) or a bedside discussion about the benefits of the program are typically not part of standard practice at most tertiary care centers. The large variation of referral mechanisms and practice standards in the US40 are problematic; however studies in other countries have shown that referral and patient education/support strategies are important to implement and can certainly overcome many health-system barriers.41,42

Study Limitations

The findings presented herein should be interpreted with caution. First, despite random assignment to study groups at the time of consent, there were more HF patients in usual care compared to the intervention group. Since HF is not covered by Medicare and may not be covered by other insurers either, this imbalance could significantly influence attendance rates. Second, some of the variables that were collected at the time of the 4-week interview were incomplete among some trial participants. Only those who participated in the first interview provided demographic data such as education. Therefore incomplete data for these participants may have affected the results. Third, although this study focused on improving rates of enrollment, physician referral is an important intermediate variable. This study did not systematically collect OCR referral data from inpatient charts. OCR referral is not generally provided during inpatient care at the participating hospital. Access to patient charts from community-based physicians was not feasible within the scope of this study to measure referral during an office visit posthospitalization. Fourth, awareness of OCR and OCR enrollment were self-reported at the time of the 12-week interview, thus these data are subject to recall-bias. Every effort was made to verify OCR enrollment among patients who did not complete the second telephone interview at 12-weeks post-hospitalization. Although 3 nonresponders (2 PN, 1 UC) were verified as having enrolled into OCR, it is possible that there were more nonresponders who enrolled in office-based OCR programs that were unknown to the investigators; thus, some enrollments may have been missed. Fifth, there was a large dropout rate at the time of the second interview (particularly among PN participants). This could potentially have affected the results and generalizability of the study. However, upon examining characteristics between those retained and not-retained, no significant differences were found. We suspect that patients in the navigated group may have been overwhelmed or possibly confused by phone calls (navigator vs. interviewer) which may explain the greater number of navigated patients lost to followup compared to usual care. In addition, self-reported awareness results may have been affected by the loss to followup. However, no sociodemographic, clinical, or health system differences were detected, within- or between-groups, when comparing the patients who were lost to followup with those who completed the 12-week phone interview. Another limitation of the study was the fidelity of the intervention implementation, with some patients discharged prior to completing a face-to-face meeting with the navigator. Future studies must determine the extent to which navigation at the bedside vs. phone and/or mailed navigation components differentially impact the outcome.

In summary, the findings suggest that nonclinically trained lay health educators can achieve significantly higher awareness of OCR compared to usual care, which is associated with higher rates of OCR program enrollment. Future research should further examine the effect of navigation to improve cardiac care transitions, especially targeting cardiac patients who are the least likely to enroll such as women, older patients, those of low socioeconomic status, and racial/ethnic minorities, yet have a significant burden of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality, and thus would benefit from secondary prevention programs such as OCR.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support:

This study was funded by GCRC GRANT # MO1RR10710 and a Targeted Research Opportunity Fusion Award with matching funds provided by the Schools of Medicine and Health Technology & Management.

The contributions of the following are gratefully acknowledged: Dr. William DeTurk, for early contributions to develop and conduct the Navigator trainings and pilot the inpatient chart review protocol; Dr. Hal Skopicki for early review of the inpatient chart review and telephone interview protocol; The Center for Survey Research staff to finalize the telephone interview protocols and collect the phone interview data; The General Clinical Research Center staff; the School of Medicine (Department of Medicine, and the Office of Scientific Affairs); the School of Health Technology and Management for their support of this research; the Navigators, Ms. Maria “Tina” Manning and Ms. Fay Wright, and Project Coordinator, Mrs. Frances Shaw; the dedicated cardiac rehabilitation staff members across Long Island for their time and expertise to develop the rationale for this study, assist with refining the protocol, and verifying the enrollment and attendance data. Lastly, we wish to thank the patients who volunteered their time to participate in this research study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None declared

Disclosures: None declared

References

- 1.World Health Organization, World Heart Federation, World Stroke Organization. [Accessed April 1, 2013];Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. policies, strategies and interventions. 2011 :1–164. Available at: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/atlas_cvd/en/index.html.

- 2.Smith SC, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update. Circulation. 2011;124:2458–2473. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heran BS, Chen JM, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD001800. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balady GJ, Ades PA, Bittner VA, et al. Referral, enrollment, and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/Secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:2951–2960. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823b21e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand SL, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1653–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, Oldridge N, Piña IL, Spertus J. AACVPR/ACCF/AHA 2010 update: Performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaBresh KA, Fonarow GC, Smith SC, Jr, et al. Improved treatment of hospitalized coronary artery disease patients with the get with the guidelines program. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6:98–105. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31812da7ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TM, Hernandez AF, Bittner V, et al. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients: Results from the AHA’s Get with the Guidelines program. Circulation. 2008;17:e465. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzini MJ, Stevens GR, Whalen D, Ozonoff A, Balady GJ. Effect of an American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines program-based clinical pathway on referral and enrollment into cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1084–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta RH, Das S, Tsai TT, Nolan E, Kearly G, Eagle KA. Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3057–3062. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nori D, Johnson J, Kapke A, Lenk D, Borzak S, Hudson M. Use of discharge-worksheet enhances compliance with evidence-based myocardial infarction care. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2002;14:43–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1022014321328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller E, Savage PD, Schneider DJ, Howland LL, Ades PA. Effect of a computerized referral at hospital discharge on cardiac rehabilitation participation rates. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29:365–369. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181b4ca75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical followup among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsey S, Whitley E, Mears VW, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of cancer patient navigation programs: conceptual and practical issues. Cancer. 2009;115:5394–5403. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benz Scott L, Gravely S, Sexton T, Brzostek S, Brown DL. Effect of patient navigation on enrollment in cardiac rehabilitation. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;11;173:244–246. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper AF, Jackson G, Weinman J, Horne R. Factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation attendance: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:541–552. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr524oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfizer Inc, in partnership with the Healthcare Association of New York State (HANAYS) [Accessed April 1, 2013];Patient Navigation in Cancer Care: Guiding Patients to Quality Outcomes (multimedia tool kit) 2008 Available at: http://www.patientnavigation.com/

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. [Accessed April 1, 2013];The Community Health Worker’s Sourcebook: A Training Manual for Preventing Heart Disease and Stroke. 2008 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/programs/nhdsp_program/chw_sourcebook/index.htm.

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grace SL, Gravely-Witte S, Kayaniyil S, Brual J, Suskin N, Stewart DE. A multi-site examination of sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation barriers by participation status. J Wome’s Health. 2009;18:209–216. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen JK, Scott LB, Stewart KJ, Young DR. Disparities in women’s referral to and enrollment in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:747–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neubeck L, Freedman SB, Clark AM, Briffa T, Bauman A, Redfern J. Participating in cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative data. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:494–503. doi: 10.1177/1741826711409326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vos C, Li X, Van Vlaenderen I, et al. Participating or not in a cardiac rehabilitation programme: factors influencing a patient’s decision. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:341–348. doi: 10.1177/2047487312437057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dankner R, Geulayov G, Ziv A, Novikov I, Goldbourt U, Drory Y. The effect of an educational intervention on coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients’ participation rate in cardiac rehabilitation programs: a controlled health care trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott LA, Ben-Or K, Allen JK. Why are women missing from outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs? A review of multilevel factors affecting referral, enrollment, and completion. J Women’s Health. 2002;11:773–791. doi: 10.1089/15409990260430927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart DE, Abbey SE, Shnek ZM, Irvine J, Grace SL. Gender differences in health information needs and decisional preferences in patients recovering from an acute ischemic coronary event. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:42–48. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000107006.83260.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaBresh KA, Gliklich R, Liljestrand J, Peto R, Ellrodt AG. Using “get with the guidelines” to improve cardiovascular secondary prevention. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:539–550. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaBresh KA, Ellrodt AG, Gliklich R, Liljestrand J, Peto R. Get with the guidelines for cardiovascular secondary prevention: pilot results. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:203–209. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown TM, Hernandez AF, Bittner V, et al. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients: findings from the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dafoe W, Arthur H, Stokes H, Morrin L, Beaton L Canadian Cardiovascular Society Access to Care Working Group on Cardiac Rehabilitation. Universal access: but when? Treating the right patient at the right time: access to cardiac rehabilitation. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:905–911. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70309-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tod AM, Lacey EA, McNeill F. ‘I’m still waiting...’: barriers to accessing cardiac rehabilitation services. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:421–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell KL, Holloway TM, Brum M, Caruso V, Chessex C, Grace SL. Cardiac rehabilitation wait times: effect on enrollment. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2011;31:373–377. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e318228a32f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jolly K, Lip GY, Taylor RS, et al. The Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation study (BRUM): a randomised controlled trial comparing home-based with centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Heart. 2009;95:36–42. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.127209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark AM, Haykowsky M, Kryworuchko J, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials of home-based secondary prevention programs for coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:261–270. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833090ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grace SL, Arthur HM, Chan C, et al. Systematizing inpatient referral to cardiac rehabilitation: A joint policy position of the Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bethell HJ, Evans JA, Turner SC, Lewin RJ. The rise and fall of cardiac rehabilitation in the United Kingdom since 1998. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29:57–61. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurewich D, Prottas J, Bhalotra S, Suaya JA, Shepard DS. System-level factors and use of cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28:380–385. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31818c3b5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gravely-Witte S, Leung YW, Nariani R, et al. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on referral and enrollment rates. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:87–96. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grace SL, Russell KL, Reid RD, et al. Effect of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on utilization rates: a prospective, controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:235–241. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]