Abstract

The dependence of the structure and function of cytoplasmic organelles in endothelial cells on constitutively produced intracellular nitric oxide (NO) remains largely unexplored. We previously reported fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus in cells exposed to NO scavengers or after siRNA-mediated knockdown of eNOS. Others have reported increased mitochondrial fission in response to an NO donor. Functionally, we previously reported that bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (PAECs) exposed to the NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5- tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (c-PTIO) developed a prosecretory phenotype characterized by prolonged secretion of soluble proteins. In the present study, we investigated whether NO scavenging led to remodeling of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Live-cell DAF-2DA imaging confirmed the presence of intracellular NO in association with the BODIPY C5- ceramide-labelled Golgi apparatus. Untreated human PAECs displayed a pattern of peripheral tubulo-reticular ER with a juxtanuclear accumulation of ER sheets. Cells exposed to c-PTIO showed a dramatic increase in ER sheets as assayed using immunofluoresence for the ER structural protein reticulon-4b/Nogo-B and the ER-resident GTPase atlastin-3, live-cell fluorescence assays using RTN4-GFP and KDEL-mCherry, and electron microscopy methods. These ER changes were inhibited by the NO donor diethylamine NONOate, and also produced by L-NAME, but not D-NAME or 8-br-cGMP. This ER remodeling was accompanied by Golgi fragmentation and increased fibrillarity and function of mitochondria (uptake of tetramethyl- rhodamine, TMRE). Despite Golgi fragmentation the functional ER/Golgi trafficking unit was preserved as seen by the accumulation of Sec31A ER exit sites adjacent to the dispersed Golgi elements and a 1.8-fold increase in secretion of soluble cargo. Western blotting and immunopanning data showed that RTN4b was increasingly ubiquitinated following c-PTIO exposure, especially in the presence of the proteasomal inhibitor MG132. The present data complete the remarkable insight that the structural integrity of three closely juxtaposed cytoplasmic organelles - Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria -is dependent on nitric oxide.

Keywords: Nitric oxide scavenging (c-PTIO), pulmonary arterial endothelial cells, organellar remodeling, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, reticulon-4b/Nogo-A, atlastin 3, ubiquitination, MG132

1. Introduction

Although reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability is considered a factor in the pathogenesis of many diseases including pulmonary arterial hypertension [1–3], the dependence of the structural integrity of cytoplasmic organelles in endothelial cells on constitutively produced nitric oxide (NO) remains largely unexplored. We previously reported that the NO scavengers 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (c-PTIO), methylene blue, N-acetylcysteine and hemoglobin all caused Golgi fragmentation in bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (PAECs)[3]. siRNA-mediated knockdown of eNOS in human PAECs also led to Golgi fragmentation [3]. The mechanism for the onset of fragmentation, but not its maintenance, required the dynamin-2 (Dyn-2) GTPase [3]. Additionally, eNOS-positive mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from wild-type mice displayed a compact Golgi apparatus compared to eNOS-negative cells in the same culture [4]. In contrast, all cells in cultures of MEFs derived from eNOS−/− mice had markedly fragmented Golgi apparatus [4]. In an independent line of investigation, Lipton and colleagues [5] reported increased mitochondrial fission in neuronal cells in response to an NO donor through a mechanism involving increased S-nitrosylation and thus activation of the GTPase dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)[5].

Surprisingly, despite development of extensive Golgi fragmentation in PAECs subjected to NO scavenging, such cells developed a prosecretory phenotype [2]. When untreated bovine PAECs were transfected with an expression vector for the soluble secreted form of horseradish peroxidase (ssHRP; a soluble cargo) and HRP secretion into the culture medium monitored on a daily basis, considerable HRP was produced through the second day after transfection, but this secretion declined rapidly to near baseline levels over the next 3–4 days. In contrast bovine PAECs exposed to c-PTIO beginning at the start of the second day after transfection of the HRP expression vector showed increased and prolonged HRP secretion for up to 6 days after HRP-expression vector transfection [2].

This prosecretory phenotype produced by reduced NO bioavailability was recapitulated recently in cultures of murine mesenchymal stem cells induced to form vascular tubes [6]. In such cultures the NO synthesis inhibitor L-NAME enhanced vascular tube formation concomitant with inducing increased VEGF-A production [6]. Conversely, NO donors inhibited vasculogenesis mediated by mesenchymal stem cells [6]. However, despite these advances there is little focus on the subcellular organellar changes that might occur within endothelial cells in response to changing levels of endogenous constitutive NO.

In the present study, we investigated whether NO scavenging leads to remodeling of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in primary human PAECs (HPAECs). Recent studies have shown that the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in eukaryotic cells is a dynamic membrane organelle consisting of the outer nuclear membrane and a peripheral network of tubules and sheets that are constantly forming and collapsing [7–10]. ER tubules and sheets have a striking contrast in structure characterized by high membrane curvature in ER tubules and low membrane curvature in ER sheets [7–10]. The mechanisms that determine peripheral ER morphology include curvature stabilizing structural proteins – the reticulons (4 family members) and DP1/Yop1p proteins (6 members)[7–9]; ER resident GTPases that are mediators of membrane tubule fusion - the atlastin family members (3 proteins), Sey1p and Rab10; and the sheet-promoting and ER lumen “spacer” protein - the cytoskeleton linking membrane protein 63 (CLIMP63; also called cytoskeleton associated protein 4, CKAP4) [7–10]. Although ER sheets are largely low curvature domains, high curvature domains exist at the boundaries of ER sheets [7,8]. Thus tubule-shaping proteins at these boundary domains can affect ER sheet morphology. We have previously investigated the dynamics of the distribution of reticulum-4b (RTN4; also called Nogo-B) and atlastin-3 (ATL3) during ER membrane remodeling from tubules and sheets to a cytoplasm filled with ER cysts generated as a result of acute knockdown of STAT5a/b in human pulmonary arterial endothelial cells [11,12].

The ratio of ER tubules and sheets has long been hypothesized to represent the functional characteristics of different cell types [7,13]. Cells specialized for protein secretion show extensive ER sheets studded with membrane-bound ribosomes. In contrast other cells contain mostly tubular ER without membrane-bound ribosomes. Thus it has been suggested that rough ER likely corresponds to ER sheets specialized for protein synthesis and secretion, while smooth ER likely corresponds to ER tubules serving functions in lipid metabolism and calcium signaling [7,8,13]. Recent discoveries identifying ER shaping proteins has led to the use of these proteins (either through overexpression or knockdown) to address the functional dichotomy between ER tubules and sheets [7,8,13].

In the present study we investigated whether the prolonged secretion phenotype which developed in endothelial cells in response to the NO scavenger c-PTIO [2] might include underlying changes in the morphology of the peripheral ER and in ER-resident proteins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemical reagents

The NO scavenger 2-(4-Carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (c-PTIO) was purchased from BioMol International (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The NO donor diethylamine NONOate sodium salt hydrate (NONOate), Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME), Nω-Nitro-D-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride D-NAME), 8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt monohydrate (8-br-cGMP), horseradish peroxidase type I, and the proteasome inhibitor Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al (also called MG-132) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). These were used as in [2,3,14]. The live-cell Golgi marker BODIPY TR C5-ceramide complexed to bovine serum albumin (C5-Cer) was purchased from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and the live-cell membrane-permeant NO reporter 4,5-diaminofluorescien diacetate (DAF-2DA) was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and were used as reported earlier [1–3]. Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) and o-phenylenediamine were from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY) and were used as before [2,3,11].

2.2 Antibody reagents

Rabbit pAbs to giantin (24586) and ATL3 (104262) was purchased from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Goat pAb to RTN4 (sc-11027) and mouse monoclonal Ab to F1-ATPase (sc-58618) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Murine mAbs to GM130 (Golgi Matrix 130 kDa protein; 610823) and Sec31A (612350) was purchased from BD Biosciences (Eugene, OR). Anti-CLIMP63 murine mAb (804-604-C100) was purchased from Enzo Life Science (Farmingdale, NY). Anti-Ub mAb was obtained from Dr. Joseph D. Etlinger (Dept. Cell Biology & Anatomy, New York Medical College, NY). Respective AlexaFluor 488- and AlexaFluor 594-tagged secondary donkey antibodies to rabbit (A-11008 and A-11012), mouse (A-21202 and A-21203) or goat (A-11055 and A-11058) IgG were from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

2.3 Cells and cell culture

Primary human pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (HPAEC) were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA). These were seeded into T-25, T-75 or 6-well plates coated with fibronectin, collagen and bovine serum albumin (respectively 1 μg/ml, 30 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml in coating medium)[3,11,12]. HPAECs were grown in Medium 200 supplemented with low serum growth supplement LSGS (Cascade Biologics, Carlsbad, CA) and were used between passages 4 and 10 [11]. HPAECs were verified using immunofluoresence assays to be positive for expression of von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and negative for smooth muscle α-actin (SMA). Typically, HPAECs were used beginning 2 days after plating and NO scavenging carried out using c-PTIO (range: 50–100 μM) with daily replenishment for up to 5 days as reported earlier [2,3]. The effects observed were blocked by prior addition of 400 μM of the NO donor NONOate [2,3]. Phase contrast microscopy was carried out daily and at the conclusion of each experiment using a Nikon Diaphot Microscope and a Nikon Coolpix digital camera. Initial live-cell imaging assays for the Golgi apparatus and for nitric oxide as in Figure 1 were carried out using the EA.hy926 human endothelial cell line [3] which were more resistant to the experimental manipulation involved.

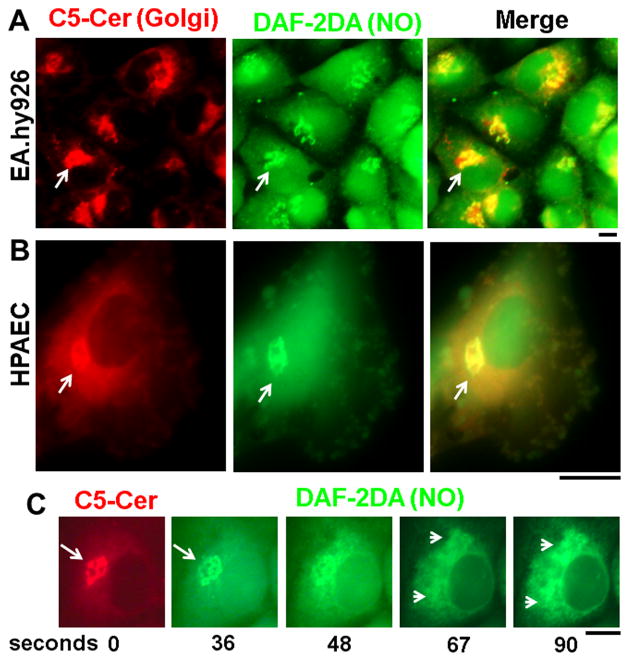

Fig. 1.

Live-cell imaging of in endothelial cells of constitutively produced intracellular NO.

Panel A: EA.hy926 cells grown in a 35 mm plate were first labeled with BODIPY TR C5-ceramide complexed to BSA (5 μM) for 30 min at 37°C, the cultures washed, then exposed to DAF-2DA (10 μM) and imaged sequentially for red and green fluorescence for the next 5–10 min using a warm stage and a 40x water-immersion objective as indicated in Materials and Methods. Figure illustrates one image compilation approximately 2 minutes after adding DAF-2DA. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Panel B. An HPAEC culture in a 35 mm plate was labeled as in Panel A but after addition of the DAF-2DA, most of the medium was removed, a cover slip placed into the plate and live-cells imaged using an 100x oil-immersion objective over the next several minutes. Scale bar = 10 μM.

Panel C. An EA.hy926 cell culture first labeled with C5-Cer was imaged at frequent intervals after addition of DAF-2DA. Panel is a compilation of selected time frames over the first 90 seconds after adding DAF-2DA. Scale bar = 10 μm.

2.4 Live-cell imaging of the Golgi apparatus and of intracellular sites

Double label live-cell imaging for the Golgi apparatus and for NO was carried out using C5-Cer (range: 1–5 μM) and DAF-2DA (10 μM) sequentially as reported earlier [1–3]. Briefly, endothelial cell cultures were first incubated with C5-Cer at 37°C for 30–40 min, followed by incubation in fresh medium for another 30 min at 37°C. The cultures were then washed twice with phenol-red free Hank’s balanced salt solution containing calcium and magnesium and 0.1 mM L-arginine. Three ml of the latter medium was replenished, made up to DAF-2DA (10 μM) and imaging in the red (C5-Cer) and green (DAF-2DA) channels commenced immediately using a 40x water immersion objective (using a Zeiss AxioImager M2 motorized microscopy system with Zeiss W N-Achroplan 40X/NA0.75 equipped with an high-resolution RGB HRc AxioCam camera and AxioVision 4.8.1 software in a 1388 × 1040 pixel high speed color capture mode). Multiple images of the same field of cells were obtained at frequent intervals for 5–10 minutes after addition of DAF-2DA [1–3].

2.5 Preparation of cultures containing enucleated cytoplasts

The cytochalasin B-centrifugation method of Prescott et al was used to prepare nucleus-free cytoplasts [12,15]. Briefly, adherent confluent cultures of HPAECs grown in coated 35 mm plastic plates were completely filled with full growth medium containing 10 μg/mL of cytochalasin B, and sealed using parafilm with little to no air bubbles and then wrapped with aluminum foil. The plates were then floated upside-down in wells of a fixed angle Sorvall GSA rotor containing 36–48 ml of distilled water. When this was spun [11,000 rpm (19,000 g) for 50 minutes at 15°C] the top/lid side of each dish typically came to face the outside. Following the spin, the cultures were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, replenished with full medium, and allowed to recover at 37°C for at least 5 hours prior to siRNA transfection or immunofluorescence assays. Cytoplasts were distinguished from nucleated endothelial cells by staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

2.6 Expression constructs for ER proteins and secreted HRP

The expression constructs for KDEL-mCherry and RTN4-GFP were used as reported previously [12,16]. The constitutive expression construct for secreted HRP (pRK34-ssHRP) was as used previously [2]. HRP secretion assays using this construct were carried out as previously reported [2].

2.7 Immunofluoresence and mCherry-and GFP-fluoresence microscopy

Cells and cytoplasts in culture were fixed using cold paraformaldehyde (4%) for 1 hr and then permeabilized using a buffer containing digitonin (50 μg/ml)/sucrose (0.3M)[12]. Immunofluoresence assays were carried out using antibodies from specific sources and corresponding to specific catalog numbers as enumerated above (dilution range 1:100 to 1:1000) as described earlier [11,12]. Respective immunofluorescence, mCherry fluorescence and GFP fluorescence was imaged as previously reported [12] using a Zeiss AxioImager M2 motorized microscopy system with Zeiss W N-Achroplan 40X/NA0.75 or Zeiss EC Plan-Neofluor 100X/NA1.3 oil objectives equipped with an high-resolution RGB HRc AxioCam camera and AxioVision 4.8.1 software in a 1388 × 1040 pixel high speed color capture mode. Controls included secondary antibodies alone, peptide competition assays and multiple different antibodies towards the same antigen. All data within each experiment were collected at identical imaging settings.

2.8 Cell extracts, immunopanning and Western blotting

The preparation of whole-cell extracts, methods for magnetic bead immunopanning using Protein A magnetic beads (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and Western blotting were as previously reported [1–3,17].

2.9 Quantitative image analyses of organellar structural parameters

This was carried out essentially as reported earlier [3]. Briefly, for Golgi and mitochondrial analyses, 40X immunofluorescence images of the respective organelle-specific proteins (giantin for Golgi and F1-ATPase for mitochondria) were evaluated using the McMaster Biophotonics Facility version of NIH Image J software and respective utility plugins (available as free downloads from www.macbiophotonics.ca/imagej/)[3]. The images were converted to 16 bit grayscale images and subjected to software-driven segmentation analysis with automatic machine-set Otsu thresholding (thus eliminating subjective investigator bias) followed by particle parameter enumeration analysis (size exclusion set at minimum of 20 pixel2). Superimposition of DAPI nuclear images allowed identification of cell numbers and enumeration of Golgi fragments per cell. Similar analyses of F1-ATPase images yielded mean area/mitochondrion [3]. For deriving tubule to sheet ratios. a modified thresholding protocol was developed to take advantage of the high-low staining intensity of RTN4 (high intensity thresholding regions represent ER sheets; low intensity thresholding regions represent ER tubules + ER sheets = total peripheral ER). Following dual-intensity thresholding, the signal areas were measured using ImageJ, the nuclear area subtracted and the subcompartments corresponding to ER sheets or ER tubules calculated as % of total peripheral ER. Typically, 100–400 cells derived from 2–5 independent experiments were imaged and quantitated for each organelle (“n” in all figures = number of cells evaluated for the designated variable); all data are expressed as mean ± SE.

2.10 Thin-section electron microscopy

Thin-section EM was carried out by the OCS Microscopy Core at NYU-Langone Medical Center in one of two ways: (a) HPAECs grown in 60 mm plates, the culture medium drained, then 1 ml 1x fixative [paraformaldehyde (2%)-glutaraldehyde (2.5%) in 0.1M Na-cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4)] was added for 2 min at room temperature, the cells then scraped, pelleted, and further fixed for 1–2 hr in 1x fixative at 4°C; or (b) 1 ml 2x fixative was added to HPAEC cultures in 35 mm plates containing 1 ml culture medium, the cells incubated at 37°C for 2min, the cultures drained, replenished with 2 ml of fresh 1x fixative and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr and then embedded in situ and sectioned en face.

2.11 Functional assay for mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE uptake)

These were carried out as reported previously [11]. Briefly, HPAEC cultures in 35 mm plates were exposed to c-PTIO (50–100 μM) for 24 hr, then washed and replenished with fresh medium (1 ml) containing 5 nM TMRE. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min, washed 4x with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), replenished with 3 ml warm PBS and imaged immediately by fluoresence microscopy. Cells in untreated and treated cultures were imaged under identical image collection settings. Fluoresence intensity/cell was expressed in arbitrary units (AU) using Image J quantitation software.

2.12 Statistical analyses

These were carried out using the two-tailed Student’s t-test in the Microsoft Excel software; for significance evaluation each individual culture (irrespective of the number of cells evaluated therein) was taken as one independent observation.

3. Results

3.1 Live-cell imaging of intracellular NO in endothelial cells

Constitutively produced intracellular NO was imaged in endothelial cells using live-cell DAF-2DA fluorescence (in green) and compared with simultaneous live-cell imaging of the Golgi apparatus using BODIPY TR C5-Ceramide (in red). Fig. 1A shows the coincidence of DAF-2DA fluorescence with the Golgi marker shortly upon DAF-2DA addition into cultures of the EA.hy926 endothelial cells (arrows). A similar observation in an HPAEC is shown at higher magnification in Fig. 1B (arrows). Moreover, Fig. 1C summarizes a sequential imaging experiment in which an endothelial cell was first imaged for C5-Cer (in red) followed by addition of DAF-2DA into the culture medium and sequential imaging. It is apparent that DAF-2DA fluoresence was first visible coincident with the Golgi apparatus (arrows) and then spread to a dispersed cytoplasmic reticular distribution (arrowheads) consistent with the structure of the endoplasmic reticulum. As controls, transfection of EA cells with siRNA to eNOS one day prior to the experiment in Fig. 1A inhibited the appearance of Golgi-localized DAF-2DA fluorescence [4], and exposure of cells to L-NAME inhibited the DAF-2DA fluorescence signal [1–3]. The live-cell imaging data in Fig. 1 provide evidence of the constitutive presence of NO within the cytoplasm of endothelial cells, especially in association with the Golgi apparatus.

3.2 Changes in ER, mitochondrial and Golgi apparatus morphology and function in human PAECs exposed to NO scavenging

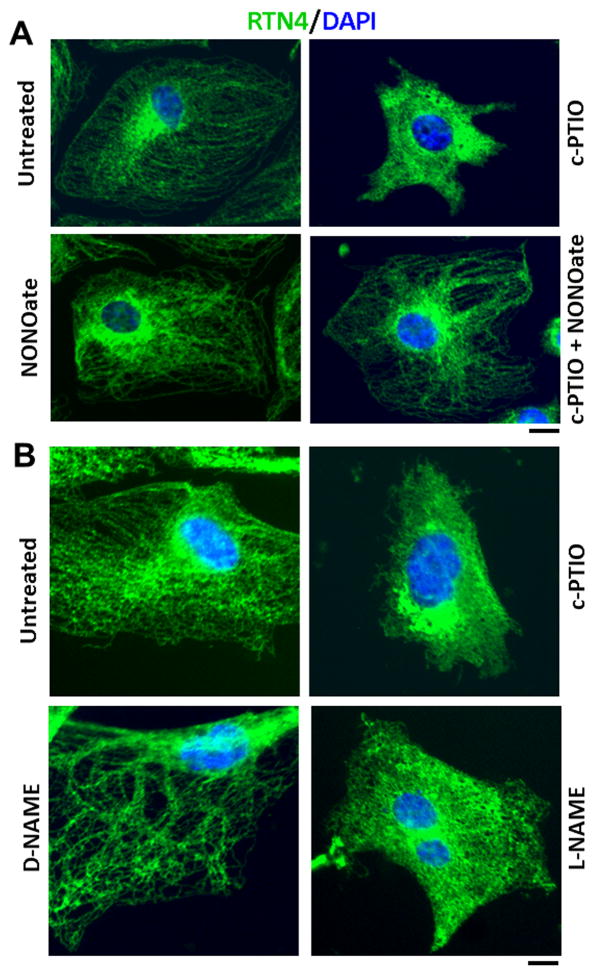

The effect of the NO scavenger c-PTIO on ER remodeling was investigated in an experiment in which HPAEC cultures were exposed to c-PTIO for one day and ER structure then evaluated by immunofluorescence display of the ER structural protein reticulon-4/Nogo-B (RTN4). The data in Fig. 2A, top row shows that untreated HPAECs displayed a peripheral tubular ER with a collection of juxtanuclear ER sheets. In contrast, cells exposed to c-PTIO showed ER sheets extending all the way to the cell periphery with an almost complete absence of ER tubules. The addition of the NO donor NONOate by itself did not trigger ER remodeling; however, NONOate blocked the ER remodeling effect of c-PTIO (Fig. 2A, bottom row). The tubule-to-sheet alteration of the ER was also elicited by exposing HPAECs for 24 hr to L-NAME, but not D-NAME (Fig. 2B). The cGMP agonist 8-br-cGMP (0.1 to 1 mM) did not affect ER structure when used by itself nor did it affect the ability of c-PTIO to elicit the tubule-to-sheet change. Additionally, the ER sheet inducing effect of c-PTIO was reversible upon washout of c-PTIO (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that the tubule-to-sheet change in the ER observed in HPAECs upon exposure to c-PTIO and L-NAME was due to NO scavenging.

Fig. 2.

Dramatic tubule-to-sheet ER remodeling in HPAECs exposed to the NO scavenger c-PTIO and L-NAME. Panel A. HPAEC cultures in a 6-well plate were exposed to c-PTIO (100 μM in this experiment; range 50–100 μM), NONOate (400 μM) or both for 1 day, fixed and ER structure evaluated using immunofluorescence for RTN4. Scale bar = 10 μm. Panel B. HPAEC cultures were exposed to L-NAME (1 mM), D-NAME (1 mM) or c-PTIO (100 μM) for 1 day, fixed and probed for RTN4. Scale bar = 10 μm.

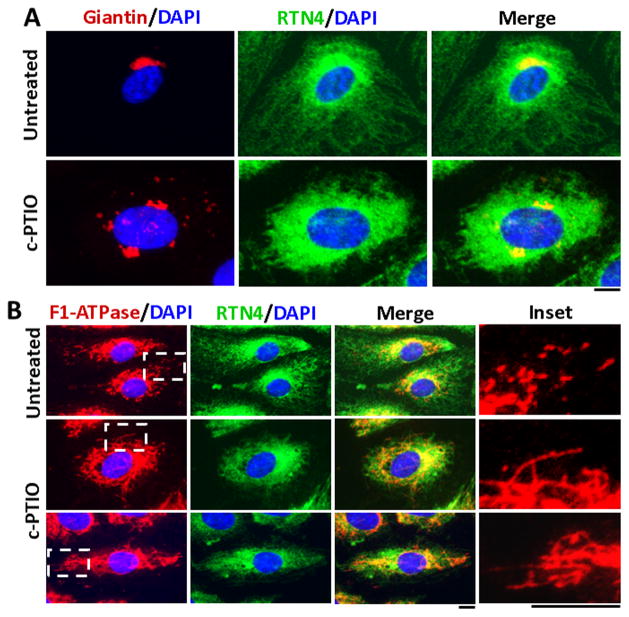

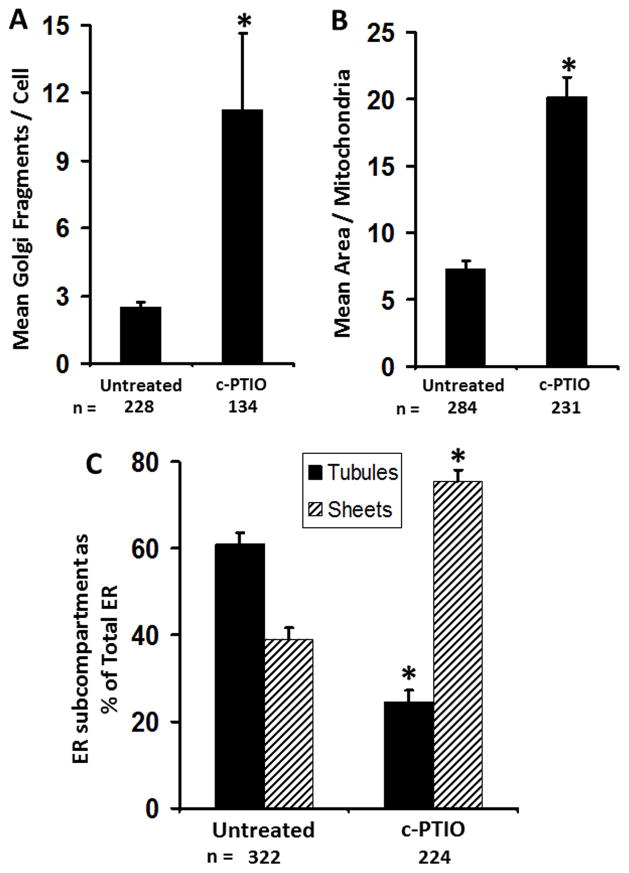

The occurrence of ER remodeling together with Golgi fragmentation and/or mitochondrial remodeling in the same cells was investigated in experiments summarized in Figs. 3 and 4. HPAEC cultures were exposed to the NO scavenger c-PTIO for 2 days and the morphology of the ER, Golgi apparatus and mitochondria evaluated using immunofluorescence assays for RTN4, giantin and F1-ATPase respectively (Fig. 3). The representative data in Fig. 3A confirm the previously demonstrated Golgi fragmentation [3]. Moreover RTN4 immunofluoresence demonstrates again a dramatic loss of the peripheral ER tubules with ER sheets extending to the cell periphery (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, the data in Fig. 3B show the increased fibrillarity of the mitochondria in cells exposed to c-PTIO.

Fig. 3.

Tubule to sheet change in endoplasmic reticulum morphylogy (ER) caused by NO scavenging accompanied by fragmentation of Golgi apparatus and increased fibrillarity of mitochondria. Panels A and B: HPAECs were exposed to c-PTIO (100 μM) for 2 days (with daily replenishment) and the structures of the ER, Golgi apparatus and mitochondria evaluated by immununofluoresence assays for RTN4, giantin and F1-ATPase respectively. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Fig. 4.

NO scavenging led to subcellular remodeling of the Golgi apparatus, mitochondria and ER structure. HPAEC cultures were treated with c-PTIO (100 μM) for 2 days (with daily replenishment) and the structures of the ER, Golgi apparatus and mitochondria evaluated by immununofluoresence assays for RTN4, giantin and F1-ATPase respectively as in Fig. 3. Panels A, B and C: summarize the extent of Golgi fragmentation, increased mitochondrial fibrillarity/size and the tubule to sheet change in the ER in experiments quantitated using the procedures summarized in Materials and Methods. “n” in all panels = number of cells evaluated for the designated variable; all data are expressed as mean ± SE. * P < 0.05 using the Student’s t test in comparison with untreated cultures.

The morphologic changes in organellar structure illustrated in Fig. 3 were quantitated using an investigator-independent machine-driven Otsu thresholding algorithm included within the Image J analysis software [3]. The respective quantitative results obtained, which are summarized in Fig. 4, show that exposure to c-PTIO induced increased Golgi fragmentation, increased mitochondrial size and a clear tubule-to sheet shift in ER morphology.

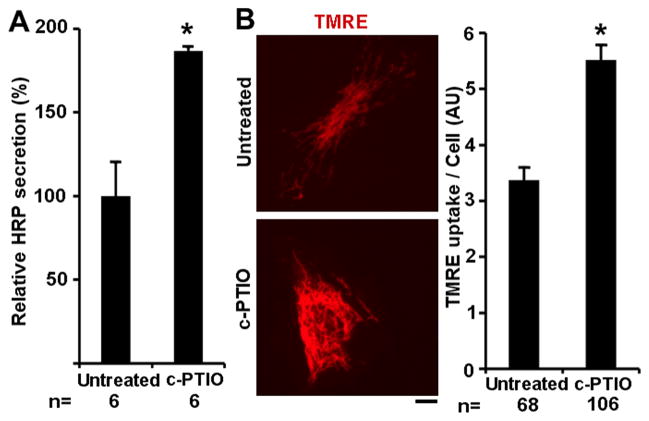

Functional changes in HPAECs exposed to c-PTIO were investigated in two ways. We verified the development of a prosecretory phenotype in HPAECs in the present experiments by carrying out the HRP synthesis and secretion assay. The data in Fig. 5A show a 1.8-fold increase in the ability of c-PTIO-treated HPAECs to secrete HRP compared to the untreated cultures in the first day after beginning of c-PTIO treatment (this is different from observations in bovine PAECs in ref. 2 which showed an inhibition in the first day after c-PTIO and then an increase from the second day onwards). We also investigated mitochondrial function using the TMRE uptake assay. The data in Fig. 5B reveal that the fibrillar mitochondria in c-PTIO-treated cells had increased TMRE uptake.

Fig. 5.

Functional assays for secretion of soluble cargo (HRP) and mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE uptake). Panel A. HPAECs plated in 35 mm cultures were transfected with the ssHRP expression vactor (pRK34-ssHRP; 10 μg/plate) in 1 ml medium. Culture medium (1 ml) was collected after 1 day from individual cultures (day 1), and duplicate cultures were left untreated or treated with 1 ml medium containing c-PTIO (100 μM). The culture medium was harvested 1 day later (day 2). HRP activity in the day 2 harvest, assayed in triplicate, was normalized for that in the day 1 harvest in that same culture to correct for variations in transfection efficiency (see method in ref. 2). Data are expressed in terms of HRP secretion in untreated cultures in the day 2 harvest as 100%. (n = number of individual HRP assays; mean ± SE; * P 0.05).

Panel B. HPAECs in 35 mm cultures were treated with c-PTIO (100 μM) for 1 day and then assayed for TMRE uptake (5 nM for 15 min). Illustration shows representative cells (scale bar = 10 μm) and the overall quantitation (n= number of cells enumerated; mean ± SE; * P <0.05).

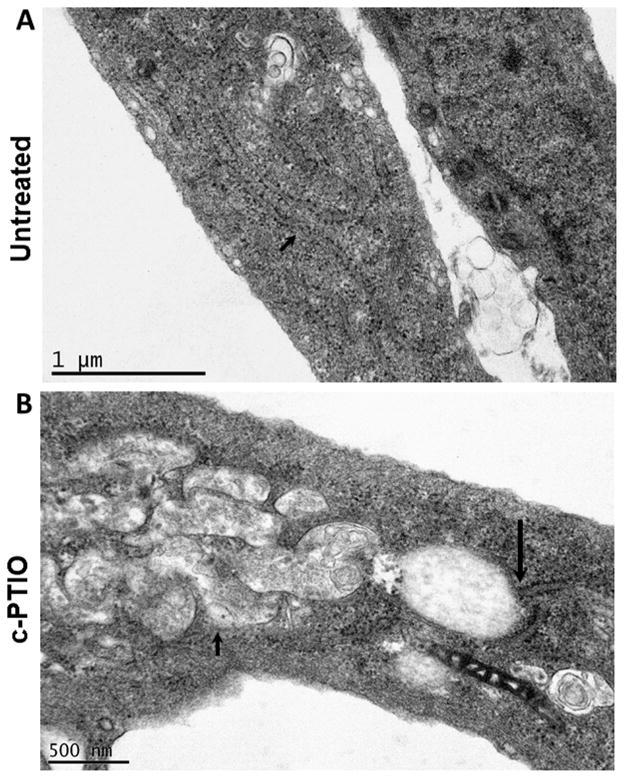

The thin-section electron microscopy data in Fig. 6A (small arrow) highlight the morphology of a ribosome-studded ER tubule in an untreated cells, and that in Fig. 6B (small arrow) point to a collection of fenestrated ER sheets in the cytoplasm of a c-PTIO-treated cell. Additionally, the data in Fig. 6B (long arrow) point to a tubule-to-sheet transition junction and this electron micrograpgh also includes an elongated fibrillar mitochondrion.

Fig. 6.

Thin-section EM showing the development of large ER sheets in HPAECs exposed to c-PTIO. Untreated (Panel A) and c-PTIO-treated (Panel B) cultures of HPAECs were fixed with paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde and organellar structure evaluated by thin-section EM. Small arrow in Panels A and B point to ER tubules and ER sheets respectively. The long arrow in Panel B points to an ER tubule-to-sheet junction.

3.3 Characterization of ER sheets produced by c-PTIO

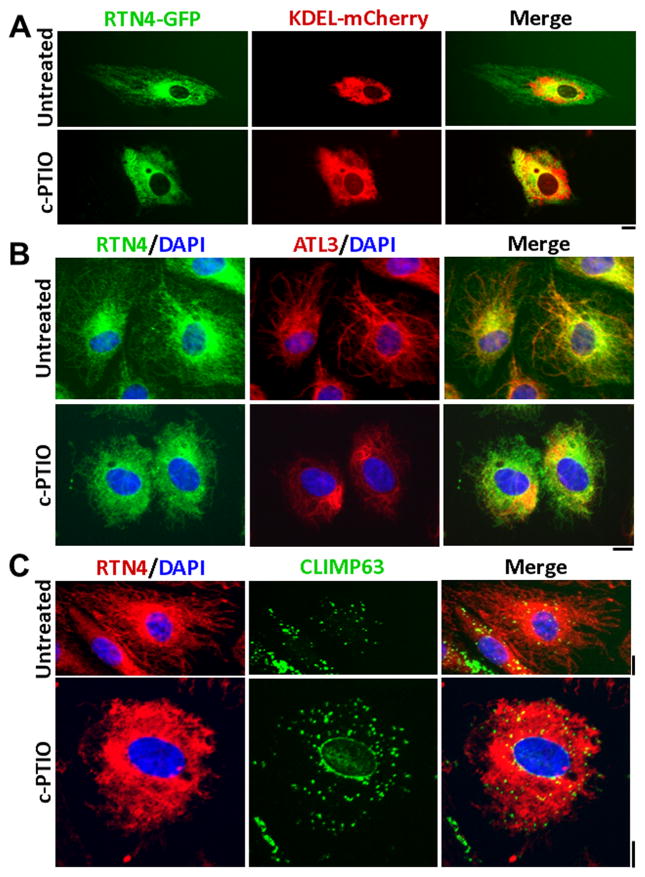

It has been suggested that specific ER resident proteins such as CLIMP63 might be enriched in ER sheets [7,8]. We characterized the ER sheets produced in HPAECs by c-PTIO using various ER markers. Fig. 7A illustrates live-cell fluorescence assays showing that as in untreated cells, ER sheets in c-PTIO-treated cells accumulated RTN4-GFP and KDEL-mCherry [16]. Fig. 7B confirms that the ER resident GTPase atlastin-3 (ATL3) is equally present in both tubules and sheets in untreated and c-PTIO-treated cells. Importantly, the punctate distribution of CLIMP63, a marker for microtubule attachment sites to the ER, is no different in ER sheets in untreated cells compared to sheets in c-PTIO-treated cells (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

NO scavenging-induced ER sheets contain normal ER components. ER sheets induced in HPAECs after 2 days of exposure to c-PTIO (100 μM) were characterized for various ER markers. Panel A: Cells were first transfected with RTN4-GFP and KDEL-mCherry and then exposed to c-PTIO followed by live-cell imaging. Panels B and C: ER sheets in cells exposed to c-PTIO (evident by RTN4 immunofluoersence) were evaluated for the GTPase atlastin-3 (ATL3) or the cytoskeleton-linking membrane protein 63 (CLIMP63; also called CKAP4). Scale bars = 10 μm.

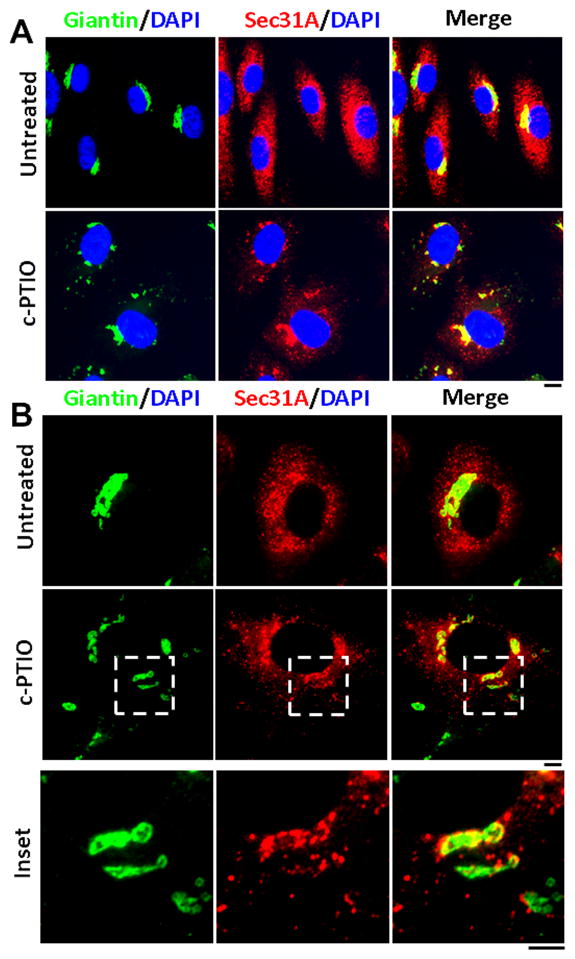

3.4 The dispersed Golgi fragments are associated with a marker for ER exit sites

In order to investigate whether the dispersed Golgi fragments in c-PTIO-treated cell cytoplasm remained part of a functionally competent ER/Golgi trafficking unit, we investigated the juxtaposition of a marker for ER vesicle exit sites (Sec31A) [7] with Golgi fragments. The data in Fig. 8 show that most of the dispersed Golgi fragments remained juxtaposed to Sec31A-postive ER exit sites. These data corroborate the secretory competence of c-PTIO-treated cells despite Golgi fragmentation.

Fig. 8.

NO scavenging induced Golgi fragments retain proximity to ER trafficking exit sites. HPAEC cultures were exposed to c-PTIO (100 μM) for 2 days and then evaluated for Golgi fragmentation (using giantin immunofluoresence) and ER trafficking exit sites (using Sec31A immunofluoresence). Data in Panel A were collected using the 40x objective and those in Panel B using a 100x objective. Scale bar in A = 10 μm; that in B = 4 μm. Compare data in insets in Panel B with thin-section EM data in Figure 6.

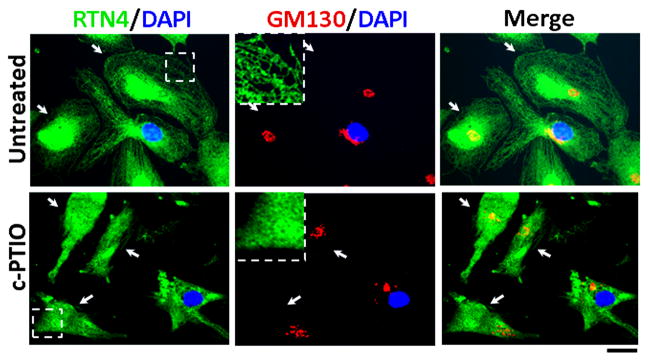

3.5 Tubule-to-sheet change in ER morphology can be produced in enucleated cytoplasts

In order to investigate whether the mechanism(s) involved in the tubule-to-sheet change upon exposure to c-PTIO might involve nuclear gene expression (such as is elicited by the canonical unfolded protein response)[18], we tested the ability of c-PTIO to cause this change in ER morphology in enucleated HPAEC cytoplasts. Cytoplasts were generated using the method of Prescott et al. [15] that was adapted by us recently for primary HPAECs [12]. Briefly adherent cells cultured in 35-mm plastic dishes were exposed to cytochalasin-B, followed by centrifugation at an angle to remove the nuclei [15] and subsequent recovery in fresh medium. This method typically yielded cultures with 60–70% enucleated cytoplasts as assayed by DAPI staining for nuclei [12]. Such cytoplast-containing cultures were then exposed to c-PTIO and the development of a tubule-to-sheet change in the ER was evaluated 1 day later. The data in Fig. 9 show that c-PTIO elicited a dominant ER sheet phenotype in cytoplasts provably lacking a nucleus (DAPI-negative). Thus the mechanism(s) that caused this tubule-to-sheet in ER morphology was nongenomic.

Fig. 9.

Tubule-to-sheet ER change upon NO scavenging does not require the nucleus (is non-genomic). HPAEC cultures containing cytoplasts were prepared using the cytochalasin B-centrifugation method, the cytoplasts allowed to recover for 5 hr and then exposed to c-PTIO (100 μm) for 1 day. ER and Golgi morphology was then assayed using immunofluoresence for RTN4 and the cis-Golgi tether GM130 in cytoplasts provably devoid of the nucleus (as assayed using DAPI). White arrows point to cytoplasts. Insets show ER tubules in an Untreated control cytoplast, and ER sheet after c-PTIO. Scale bar = 25 μm.

3.6 Increased ubiquitination of RTN4

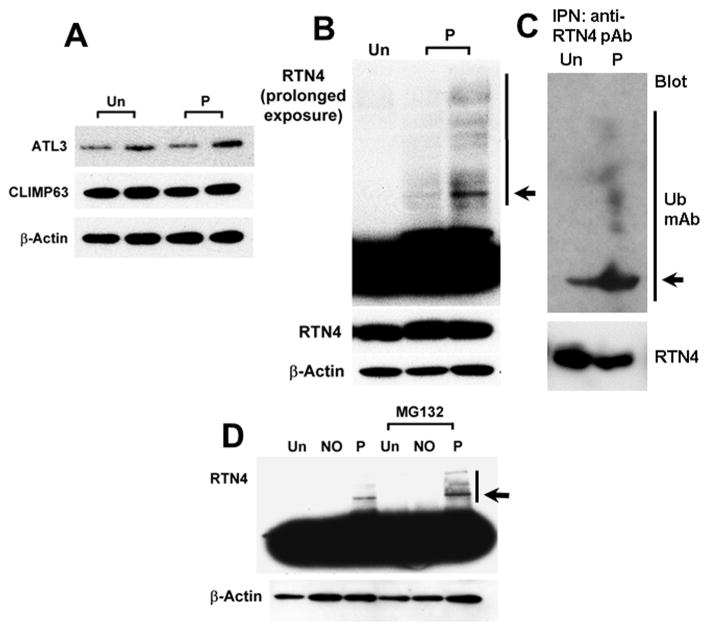

The dramatic effect of NO scavenging on ER morphology suggested that ER structural proteins might be NO-sensitive. Protein expression levels of ATL3, CLIMP63, and RTN4 remained largely unchanged following NO scavenging (Fig. 10A). However, the increased presence of covalently derivatized complexes of RTN4 with higher molecular mass was observed (Fig. 10B), were verified to represent a pool of ubiquitinated RTN4 molecules (Fig. 10C). Moreover the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 increased the accumulation of such higher molecular mass derivatives of RTN4 (Fig. 10D). Thus there was increased ubiquitination of RTN4 in c-PTIO-treated cells.

Fig. 10. Increased ubiquitination of RTN4 upon NO scavenging.

Panels A and B: Cell extracts were prepared from HPAEC cultures exposed to c-PTIO (P) or left untreated (Un) and assayed by Western blotting for ATL3 and CLIMP63 (Panel A, in duplicate lanes) or RTN4b (Panel B, lower part) using β-actin as a loading control (amount of loaded protein in the middle lane in Panel B is half that in the right-most lane). The upper part of panel B is a longer exposure of the blot showing higher molecular-mass RTN4 bands (arrow and line).

Panel C: Cell extracts (matched amounts of Un and P) were subjected to magnetic-bead immunopanning using anti-RTN4 pAb followed by Western blotting using an anti-Ub mAb. Arrow points to ubiquinated RTN4; the line to higher molecular mass derivatives.

Panel D: Cell extracts prepared from HPAEC cultures treated for 2 days with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (25 μM), c-PTIO (100 μM) or NONOate (400 μM) in various combinations as indicated were assayed by Western blotting for RTN4 and then β-actin. Arrow and line point to higher molecular mass complexes of RTN4b.

3.7 The proteasomal inhibitor MG132 produces a compact perinuclear ER sheet

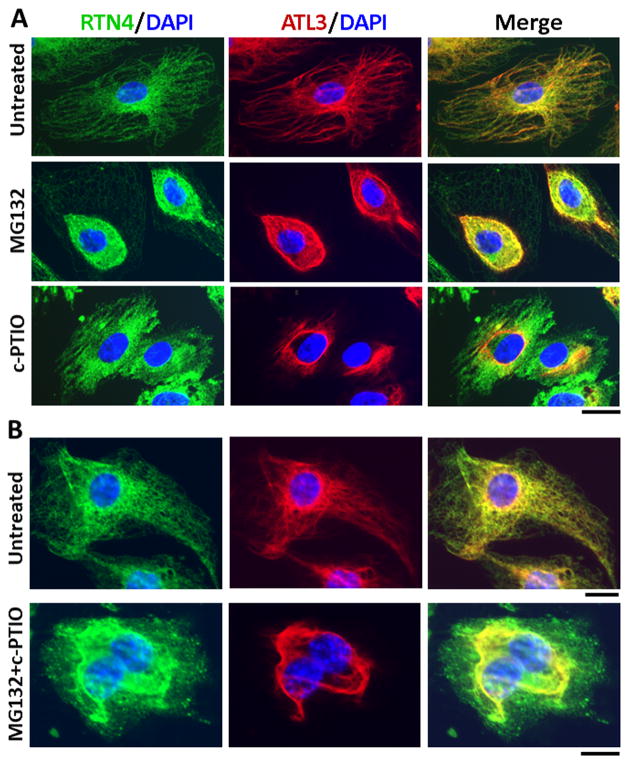

The observation that ER structural proteins themselves might be ubiquitinated, led us to investigate the possibility that the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 might itself cause morphologic changes in the ER. Fig. 11A summarizes the observations that MG132 by itself caused a dramatic change in ER morphology resulting in (a) a compact circumnuclear formation of an ER sheet, and (b) the selective enrichment of ATL3 in this ER sheet with its depletion from the remaining peripheral ER tubules (Fig. 11A, middle row). This change is clearly different from that produced by c-PTIO (Fig. 11A, bottom row). Peripheral ER sheets containing RTN4 were observed when cells were exposed to the combination of MG132 and c-PTIO; however, again, there was a cell centric accumulation of ATL3 with a distinct demarcating border between an ATL3-enriched circumnuclear region and the peripheral ATL3-depleted region (Fig. 11B).

Fig. 11.

The proteasomal inhibitor MG132 induces a dramatically delimited circumnuclear ER sheet region with depletion of the ATL3 GTPase from the periphery. Panel A. HPAEC cultures were left untreated or exposed to either MG132 (25 μM) or c-PTIO (100 μM) for 2 days and the ER structure then evaluated using immunofluoresence assays for RTN4 and ATL3. Panel B. HPAEC cultures were left untreated or exposed to a combination of MG132 (25 μM) and c-PTIO (100 μM) for 1 day. Scale bars = 25 μm.

4. Discussion

We investigated the influence of constitutively produced intracellular NO on the structure of cytoplasmic organelles in endothelial cells. The presence of constitutive intracellular NO was confirmed using live-cell imaging and the cell-permeant reporter DAF-2DA. The DAF-2DA fluorescence initially colocalized with the C5-ceramide-labelled Golgi apparatus and subsequently spread to a cytoplasmic reticular structures. The depletion of NO bioavailability by the use of the scavengers c-PTIO or L-NAME led to a marked tubule to sheet remodeling of the ER, fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus and increased mitochondrial fibrillarity, accompanied by the development of a prosecretory phenotype in HPAECs. The ER sheets produced by c-PTIO exposure retained the structural protein RTN4 (the b isoform is predominant in endothelial cells), and the ER-resident GTPase ATL3 and maintained a punctate distribution of CLIMP63 and Sec31A sites. In such cells the functional secretory unit remained intact in that ER exit sites (marked by Sec31A) remained adjacent to the dispersed Golgi elements. In live-cell imaging such ER sheets accumulated the soluble cargo KDEL-mCherry. The tubule-to-sheet remodeling in response to c-PTIO did not require the cell nucleus i.e. did not involve changes in gene expression changes, but was accompanied by increased ubiquitination of RTN4.

The separation of the peripheral ER into tubules and sheets has led to questions about the mechanisms that determine this morphological distinction and their respective functions [7–9,13]. Observations of extensive sheets in cells that secrete “professionally”, such as immunoglobulin-secreting B cells or zymogen-secreting pancreatic cells led to the suggestion that ER sheets might represent a specialization geared towards protein synthesis secretion [7,8,13]. The present data showing a marked tubule-to-sheet change in ER morphology in HPAECs exposed to the NO scavengers c-PTIO or L-NAME, concomitant with development of a prosecretory phenotype is consistent with this view. Untreated primary HPAECs displayed an ER morphology that was predominantly tubular. In contrast cells exposed to c-PTIO or L-NAME contained stacks of fenestrated ER sheets that extended to the cell periphery. Cells exposed to c-PTIO also had elongated mitochondria but fragmented and dispersed Golgi elements. Despite the dramatic organellar remodeling, the ER/Golgi functional units remained intact as evidenced by the continued juxtaposition of the Sec31A-containing ER exit sites adjacent to the fragmented Golgi elements in immunofluorescence assays and by thin-section electron microscopy (EM data not shown).

We and others have previously shown that NO scavenging by c-PTIO led to the driving of bovine PAECs into mitosis and cell proliferation (ref. 2 and citations therein). Whether there is a mechanistic relationship between Golgi fragmentation and increased entry into mitosis is unknown. Ramon y Cajal in 1914 reported Golgi fragmentation in hypoxic neurons [19]. More recently, we reported Golgi changes in PAECs exposed to hypoxia [1]. Whether the combination of hypoxia plus NO scavenging together produce increased biological effects remains is unexplored.

In investigating the biochemical changes in ER structural proteins in cells subjected to c-PTIO exposure, we observed the increased ubiquitination of RTN4. While the ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery has been extensively investigated in the context of proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins [20–23], the demonstration of the ubiquitination of the ER structural protein RTN4 is novel. The mechanism(s) for how intracellular NO regulates this RTN4-ubiquitination pathway represent a new area of biochemical dissection.

The proteasomal inhibitor MG132 by itself also produced a dramatic change in ER morphology. After exposure to MG132, the ER in endothelial cells segregated into a sharply demarcated circumnuclear ER sheet region with a more peripheral network of tubues extending to the plasma membrane. It was remarkable that the ATL3 GTPase was markedly enriched in this ER sheet region and that in such cells the peripheral ER tubules were largely depleted of ATL3. While several previous investigators have studied the ER stress and unfolded protein response triggered by exposure of cells to MG132, including in the context of blood pressure regulation [20–24], the dramatic bifurcation of ER morphology into extensive peripheral tubules that were depleted of ATL3 and a compact circumnuclear ATL3-rich sheet region observed in MG132-treated vascular cells is novel.

Very recently we have emphasized another dramatic aspect of ER remodeling in endothelial cells [11,12]. Endothelial cells exposed to siRNAs for the transcription factors STAT5a and STAT5b displayed a marked tubule to cyst change in the ER within 12–16 hr of STAT5 knockdown. In this instance, the cysts represented dilated ER elements studded with ribosomes and the overall regions of cystic change extended to the boundary of the endoplasm but did not include the ectoplasm [11,12]. The cyst zone was demarcated by deposition of RTN4 and ATL3 with accumulation of CLIMP63 in the intercystic membranes and in the cyst lumens. Remarkably, this tubule-to-cyst change included the nuclear envelope in that the outer nuclear membrane was bulged outward into large cysts and the nuclear shape was distorted (lunate distortion) into a concavity at such cysts with increased deposition of RTN4 on the convex sides of the nuclear envelopes [11]. In contrast with the typical ER stress response or the typical unfolded protein response pathways which include changes in nuclear gene expression [18–23], the cystic ER change was observed in enucleated cytoplasts [12]. Thus, this ER remodeling highlighted a novel nongenomic cytoplasmic function for STAT5 proteins, although the latter are well-known as genomic transcription factors. The ER remodeling due to acute knockdown of STAT5a/b in vascular cells (endothelial and smooth muscle) was accompanied by Golgi fragmentation, mitochondrial fragmentation, reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and reduced anterograde trafficking of vesicular stomatis virus G glycoprotein [11]. Biochemically, STAT5a and STAT5b species were shown to be present in immunoprecipitable complexes with ATL3 [11].

To summarize, the present study defines a novel ER remodeling response in vascular cells to reduced NO bioavailability. The data define a novel tubule-to-sheet remodeling of the ER in response to NO scavenging in endothelial cells. The new data complete the remarkable insight that, at least in endothelial cells, the structural integrity of all three of these closely associated cytoplasmic organelles – the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria - is dependent on nitric oxide.

Highlights.

We evaluated structural remodeling of organelles in ECs upon NO scavenging

NO scavenging caused a marked tubule-to-sheet change in endoplasmic reticulum

NO scavenging caused Golgi apparatus fragmentation

NO scavenging caused increased mitochondrial fibrillarity and function

Functionally, the above changes underlie a prosecretory phenotype

Acknowledgments

Grants

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grants R01 HL-087176, R03 HL-114601 (both to Dr. Pravin B. Sehgal), and F31 HL107013 (to Dr. Jason E. Lee). The funding sources had no involvement in any aspect of this manuscript.

The KDEL-mCherry and RTN4-GFP expression plasmids were gifts from Dr. Gia Voeltz (University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO). The anti-Ub mAb was a gift from Dr. Joseph D. Etlinger (New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mukhopadhyay S, Xu F, Sehgal PB. Aberrant cytoplasmic sequestration of eNOS in endothelial cells after monocrotaline, hypoxia, and senescence: live-cell caveolar and cytoplasmic NO imaging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1373–H1389. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00990.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J, Reich R, Xu F, Sehgal PB. Golgi, trafficking, and mitosis dysfunctions in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells exposed to monocrotaline pyrrole and NO scavenging. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L715–L728. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00086.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JE, Patel K, Almodar S, Tuder RM, Flores SC, Sehgal PB. Dependence of Golgi apparatus integrity on nitric oxide in vascular cells: implications in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1141–H1158. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00767.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JE. PhD Thesis. New York Medical College; Valhalla, New York, USA: 2012. Subcellular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho DH, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates β-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science. 2009;324:102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes SA, Rangel EB, Premer C, Duke RA, Cao Y, Flores V, Balkan W, Rodrigues CO, Schally AV, Hare JM. S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) enhances vasculogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220185110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibata Y, Hu J, Kozlov MM, Rapoport TA. Mechanisms shaping the membranes of cellular organelles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:329–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibata Y, Shernesh T, Prinz WA, Palazzo AF, Kozlov MM, Rapoport TA. Mechanisms determining the morphology of the peripheral ER. Cell. 2010;143:774–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman JR, Voeltz GK. The ER in 3D: a multifunctional dynamic membrane network. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.English AR, Voeltz GK. Rab10 GTPase regulates ER dynamics and morphology. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:169–178. doi: 10.1038/ncb2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JE, Yang YM, Liang FX, Gough DJ, Levy DE, Sehgal PB. (2012) Nongenomic STAT5-dependent effects on Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum structure and function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C804–C820. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00379.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JE, Yang Y-M, Yuan H, Sehgal HPB. Definitive evidence using enucleated cytoplasts for a nongenomic basis for the cystic change in endoplasmic reticulum structure caused by STAT5a/b siRNAs. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C312–C323. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00311.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shibata Y, Voeltz GK, Rapoport TA. Rough sheets and smooth tubules. Cell. 2006;126:435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rayanade RJ, Patel K, Ndubuisi M, Sharma S, Omura S, Etlinger JD, Pine R, Sehgal PB. Proteasome-and p53-dependent masking of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) factors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4659–4662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescott DM, Myerson D, Wallace J. Enucleation of mammalian cells with cytochalasin B. Exptl Cell Res. 1972;71:480–485. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zurek N, Sparks L, Voeltz G. Reticulon short hairpin transmembrane domains are used to shape ER tubules. Traffic. 2011;12:28–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehgal PB, Mukhopadhyay S, Xu F, Patel K, Shah M. (2007) Dysfunction of Golgi tethers, SNAREs, and SNAPs in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1526–L1542. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00463.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cajal SR. Algunas vatiaciones fisiologicas y patologicas del aparato reticular de Golgi. Trab Lab Inv Biol Madrid. 1914;12:127–227. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh SH, Lim SC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated autophagy/apoptosis induced by capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) and dihydrocapsaicin is regulated by the extent of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in WI38 lung epithelial fibroblast cells. J Pharmacol Exptl Therapeut. 2009;329:112–122. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.144113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amanso AM, Debbas V, Laurindo FRM. Proteasome inhibition represses unfolded protein response and Nox4, sensitizing vascular cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced death. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.StPierre P, Dang T, Joshi B, Nabi IR. Peripheral endoplasmic reticulum localization of the Gp78 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1727–1737. doi: 10.1242/jcs.096396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vardarajan S, Bampton ETW, Smalley JL, Tanaka K, Caves RE, Butterworth M, Wei J, Pellechia M, Mitcheson J, Grant TW, Dinsdale D, Cohen GM. A novel cellular stress response characterized by a rapid reorganization of membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Death Differen. 2012;19:1896–1907. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang B, Wang S, Wang Q, Zhang W, Viollet B, Zhu Y, Zou MH. Aberrant endoplasmic reticulum stress in vascular smooth muscle increases vascular contractility and blood pressure in mice deficient of AMP-activated protein kinase-α2 in vivo. Art Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:595–604. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]