Abstract

Non-synonymous mutations affecting both alleles of PCSK1 (proprotein convertase 1/3) are associated with obesity and impaired prohormone processing. We report a proband who was compound heterozygous for a maternally inherited frameshift mutation and a paternally inherited 474kb deletion that encompasses PCSK1, representing a novel genetic mechanism underlying this phenotype. Although pro-vasopressin is not a known physiological substrate of PCSK1, the development of central diabetes insipidus in this proband suggests that PCSK1 deficiency can be associated with impaired osmoregulation.

Keywords: Obesity, Prohormones

Highlights

-

•

We identify a fourth patient with PCSK1 deficiency.

-

•

The null phenotype of PCSK1 deficiency includes obesity and neuroendocrine abnormalities.

-

•

We extend the clinical phenotype to include central diabetes insipidus, as well as severe obesity and impaired prohormone processing.

1. Introduction

Proprotein convertases (PCs) are a family of serine endoproteases that cleave inactive pro-peptides into biologically active peptides [1]. Two family members, Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin types 1 and 2 (PCSK1 and PCSK2) are selectively expressed in neuroendocrine tissues where they cleave a broad but specific set of prohormones including pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), prothyrotrophin releasing hormone (TRH), proinsulin, proglucagon, and progonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) [2–9]. Congenital deficiency of PCSK1 has previously been reported in three unrelated probands with severe hyperproinsulinemia, malabsorptive diarrhea, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, partial central defects in the adrenal and thyroid axes and severe obesity [10–12]. At least some of these phenotypes can be explained by the known or suggested involvement of PCSK1 in the processing of proinsulin, proopiomelanocortin, proglucagon, proGnRH and proTRH [1]. We describe the fourth patient with PCSK1 deficiency whose phenotype, in addition to the above, included central diabetes insipidus.

2. Research design and methods

Direct nucleotide sequencing of the PCSK1 gene was carried out as previously reported [10]. SNP microarray analysis was performed using the Affymetrix 6.0 platform using 500 ng of total genomic DNA. Data was analyzed using Affymetrix Genotyping Console Browser v.3.01. Multiplex Ligation-independent Probe Amplification (MLPA) probes in the PCSK1 gene region (chr5:95751875-95774445) were designed following MRC-Holland (The Netherlands) recommendations (http://www.mlpa.com/) and sequences are available upon request. MLPA Hybridization, ligation and PCR were carried out using 200 ng of genomic DNA and the SALSA-MLPA kit (MRC-Holland, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The MLPA PCR products (1 μl) were mixed with 0.5 μl GeneScan™-500 ROX™ size standard (Applied Biosystems, UK) and 10 μl of HiDi formamide (Applied Biosystems, UK) and separated on an ABI 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, UK) and electrophoresis data extracted using GeneMapper software v4.0 (Applied Biosystems, UK).

3. Results

The male proband weighed 3.8 kg at birth. Diarrhea began at three days of life and persisted despite oral feeding with multiple formula changes. Endoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed a grossly normal esophagus, stomach and duodenum, and scattered ulcers in the sigmoid colon. Pathology reported eosinophils present in the duodenum, stomach and colon and eosinophilic cryptitis in the colon consistent with “allergic colitis”. Due to continued diarrhea and failure to thrive, parenteral nutrition together with continuous nasogastric feeds of an amino-acid based formula was instituted at 2 months of age. Watery diarrhea, however, continued. At 3 months the patient was admitted for sepsis associated with his intravenous catheter. Within 2 h of central line removal, his blood glucose fell to 33 mg/dl, with a low serum cortisol of 11.60 μg/dl (normal > 18 μg/dl) and a normal growth hormone (13.8 ng/ml). Thyroid function was consistent with central hypothyroidism (TSH 1.60 μIU/ml) with free thyroxine levels of 0.78 ng/dl (normal 0.9–1.8 ng/dl) and a low testosterone (28 ng/dl) and micropenis noted on clinical examination. In view of these findings, he was diagnosed with partial hypopituitarism and started on hydrocortisone and thyroxine replacement therapy. Monthly testosterone injections for 3 months resulted in the normalization of his penile size. Persistent polydipsia and polyuria were noted in the third year of life. Following restriction of fluid overnight, his serum Na was 145 mEq/l, Cl 107 mEq/l and osmolality was 304 mOsm/kg (urine specific gravity was 1.010 and osmolality 386 mOsm/kg), confirming the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus. He was started on oral desmopressin which led to a marked improvement in symptoms and electrolyte abnormalities.

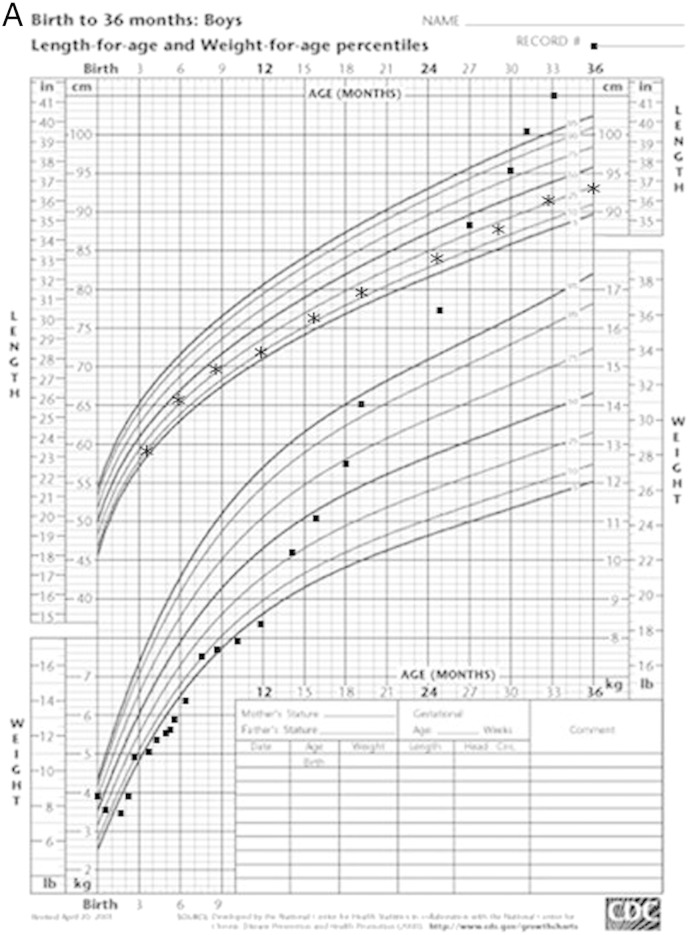

From 12 months, rapid weight gain began despite an apparent average caloric intake of ~ 70 kcal/kg/day. Some solid foods were introduced for the first time at about 14 months, and this resulted in improved stool consistency and less frequent diarrhea. By 24 months old, the child was grossly obese (Fig. 1A). The amino-acid based formula was discontinued at 3 years of age.

Fig. 1.

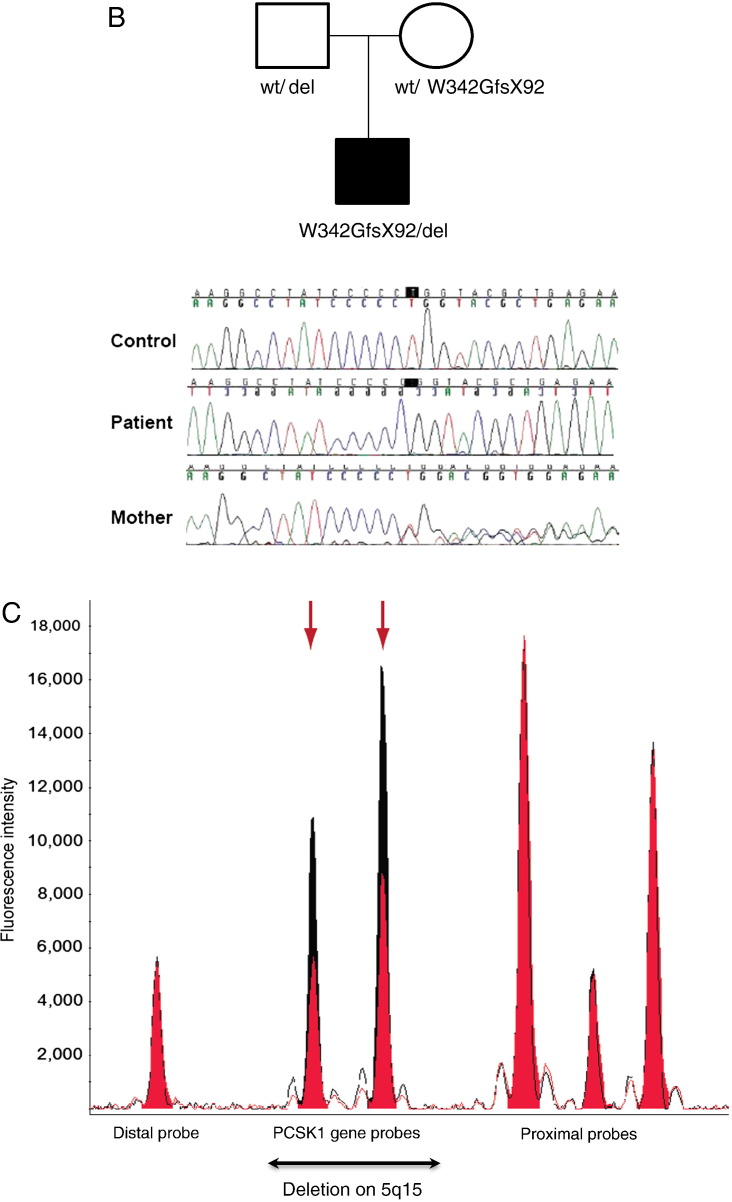

A. Growth chart of proband demonstrating marked failure to thrive over first 2 months; stabilization of weight gain from 2 months (with introduction of parenteral nutrition and an amino acid based formula) and excessive weight gain from 1 year. B. Family tree with chromatograms. Wildtype (Wt); deletion (del). C. MLPA confirmation of 474kb deletion of 5q15-q15 (95669703-96143955). Patient's MLPA traces are in red overlayed on the control MLPA traces in black. MLPA probes for genes in the region of interest are detailed below. Two of the MLPA probes are positioned within the PCSK1 gene and appear to be deleted in the patient (arrows), and two are on either side of the deleted region on chromosome 5q15 (distal and proximal probes), and they are identical to the normal control.

In view of the combination of chronic diarrhea, rapid weight gain and selective hypopituitarism, the possibility of PCSK1 deficiency was entertained. A nonfasting plasma insulin was low (0.2 μU/ml) but proinsulin was > 200 μU/ml. Direct nucleotide sequencing of PCSK1 revealed an apparently homozygous single base pair deletion which results in a frameshift after Pro 341, with the introduction of 91 abnormal amino acids terminating in a premature stop codon (W342GfsX92). The mutation is located within a region that encodes the catalytic domain and thus would be expected to abolish PCSK1 function. The proband's mother was found to be heterozygous for the same mutation. However, no PCSK1 mutation was found in his father. SNP microarray analysis revealed a 474kb interstitial deletion of 5q15-q15 (95669703-96143955) which contains three genes, PCSK1, calpastatin and endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1. This deletion was confirmed by Multiplex Ligation-independent Probe Amplification (MLPA) and was also found in the patient's father (Figs. 1B and C). Thus, the patient had inherited a large deletion that encompassed the PCSK1 gene and also a frameshift mutation within the gene resulting in the loss of both alleles and the phenotype of PCSK1 deficiency. Common heterozygous variants in PCSK1 have been associated with late-onset obesity [13]. However, both parents of this proband were of normal weight and had no evidence of intestinal or endocrine abnormalities. While these findings do not preclude a more subtle effect of some PCSK1 variants on body weight, the loss of both PCSK1 alleles appears to be necessary for the complete phenotype.

4. Discussion

We describe the fourth patient with PCSK1 deficiency due to the combination of a maternally inherited frameshift mutation leading to a premature stop and a paternal deletion on chromosome 5 encompassing PCSK1 and two adjacent genes. This patient differs significantly from the three previous cases all of which involved homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for missense or splice site mutations [10–12]. In this case one allele was deleted and the other disrupted by a 91 amino acid insertion followed by a premature stop codon occurring within the catalytic domain. While some residual PCSK1 enzymatic activity could conceivably have persisted in the three previously reported cases it seems highly likely that this patient represents the null phenotype of PCSK1.

The development of central diabetes insipidus in our patient suggests that PCSK1 may be involved in the full functioning or central sensing of osmolality in humans. Whether this is due to the failure of provasopressin processing or to some other malfunction of osmoreception or vasopressin production or release is unknown. Vasopressin is synthesized in hypothalamic neurons expressing both PCSK1 and PCSK2 [5]. In mice, both PCSK1 and PCSK2 are involved in the processing of pro-vasopressin to vasopressin, suggesting that a degree of redundancy may exist in vivo [6,14,15]. In summary we report the fourth patient with PCSK1 deficiency. The finding of diabetes insipidus in this patient, and clinical features suggestive of this diagnosis in one patient previously reported by us [12], suggest that this potentially clinically significant and treatable abnormality should be sought in future patients presenting with this syndrome.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

ISF and SOR were supported by the Wellcome Trust, the MRC Centre for Obesity and Related Disorders and the UK NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Seidah N.G. The proprotein convertases, 20 years later. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;768:23–57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-204-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaner P., Todd R.B., Seidah N.G., Nillni E.A. Processing of prothyrotropin-releasing hormone by the family of prohormone convertases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19958–19968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barge-Schaapveld D.Q., Maas S.M., Polstra A., Knegt L.C., Hennekam R.C. The atypical 16p11.2 deletion: a not so atypical microdeletion syndrome? Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155A:1066–1072. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjannet S., Rondeau N., Day R., Chretien M., Seidah N.G. PC1 and PC2 are proprotein convertases capable of cleaving proopiomelanocortin at distinct pairs of basic residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:3564–3568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong W., Seidel B., Marcinkiewicz M., Chretien M., Seidah N.G., Day R. Cellular localization of the prohormone convertases in the hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei: selective regulation of PC1 in corticotrophin-releasing hormone parvocellular neurons mediated by glucocorticoids. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:563–575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00563.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabreels B.A., Swaab D.F., de Kleijn D.P., Seidah N.G., Van de Loo J.W., Van de Ven W.J., Martens G.J., van Leeuwen F.W. Attenuation of the polypeptide 7B2, prohormone convertase PC2, and vasopressin in the hypothalamus of some Prader–Willi patients: indications for a processing defect. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:591–599. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.2.4542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangaraju N.S., Harris R.B. GAP-releasing enzyme is a member of the pro-hormone convertase family of precursor protein processing enzymes. Life Sci. 1993;52:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90134-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rouille Y., Martin S., Steiner D.F. Differential processing of proglucagon by the subtilisin-like prohormone convertases PC2 and PC3 to generate either glucagon or glucagon-like peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26488–26496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smeekens S.P., Montag A.G., Thomas G., Albiges-Rizo C., Carroll R., Benig M., Phillips L.A., Martin S., Ohagi S., Gardner P. Proinsulin processing by the subtilisin-related proprotein convertases furin, PC2, and PC3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:8822–8826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson R.S., Creemers J.W., Ohagi S., Raffin-Sanson M.L., Sanders L., Montague C.T., Hutton J.C., O'Rahilly S. Obesity and impaired prohormone processing associated with mutations in the human prohormone convertase 1 gene [see comments] Nat. Genet. 1997;16:303–306. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson R.S., Creemers J.W., Farooqi I.S., Raffin-Sanson M.L., Varro A., Dockray G.J., Holst J.J., Brubaker P.L., Corvol P., Polonsky K.S. Small-intestinal dysfunction accompanies the complex endocrinopathy of human proprotein convertase 1 deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1550–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI18784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farooqi I.S., Volders K., Stanhope R., Heuschkel R., White A., Lank E., Keogh J., O'Rahilly S., Creemers J.W. Hyperphagia and early-onset obesity due to a novel homozygous missense mutation in prohormone convertase 1/3. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:3369–3373. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benzinou M., Creemers J.W., Choquet H., Lobbens S., Dina C., Durand E., Guerardel A., Boutin P., Jouret B., Heude B. Common nonsynonymous variants in PCSK1 confer risk of obesity. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:943–945. doi: 10.1038/ng.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardiman A., Friedman T.C., Grunwald W.C., Jr., Furuta M., Zhu Z., Steiner D.F., Cool D.R. Endocrinomic profile of neurointermediate lobe pituitary prohormone processing in PC1/3- and PC2-Null mice using SELDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;34:739–751. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wardman J.H., Zhang X., Gagnon S., Castro L.M., Zhu X., Steiner D.F., Day R., Fricker L.D. Analysis of peptides in prohormone convertase 1/3 null mouse brain using quantitative peptidomics. J. Neurochem. 2010;114:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]