Abstract

Purpose

Sexual health refers a state of lifespan well-being related to sexuality. Among young people, sexual health has multiple dimensions, including the positive developmental contributions of sexuality, as well as the acquisition of skills pertinent to avoiding adverse sexual outcomes such as unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Existing efforts to understand sexual health, however, have yet to empirically operationalize a multi-dimensional model of sexual health and to evaluate its association to different sexual/prevention behaviors.

Methods

Sexual health dimensions and sexual/prevention behaviors were drawn from a larger longitudinal cohort study of sexual relationships among adolescent women (N =387, 14–17 years). Second order latent variable modeling (AMOS/19.0) evaluated the relationship between sexual health and dimensions and analyzed the effect of sexual health to sexual/prevention outcomes.

Results

All first order latent variables were significant indicators of sexual health (β: 0.192 – 0.874, all p < .001). Greater sexual health was significantly associated with sexual abstinence, as well as with more frequent non-coital and vaginal sex, condom use at last sex, a higher proportion of condom-protected events, use of hormonal or other methods of pregnancy control and absence of STI. All models showed good fit.

Conclusions

Sexual health is an empirically coherent structure, in which the totality of its dimensions is significantly linked to a wide range of outcomes, including sexual abstinence, condom use and absence of STI. This means that, regardless of a young person’s experiences, sexual health is an important construct for promoting positive sexual development and for primary prevention.

Keywords: Sexual health, Structural equation modeling, Sexual and prevention behavior, Adolescent women

Sexual health refers to a state of optimal well-being related to sexuality through the lifespan [1,2]. Among young people, a sexual health perspective differs from traditionally risk-focused perspectives by emphasizing the positive developmental contributions that sexuality provides to adolescent well-being within the context of romantic, family, and social relationships [3–5]. Moreover, a sexual health perspective addresses adverse out-comes, such as sexually transmitted infections (STI) and unintended pregnancy, by focusing on the developmental integration of important skills, such as personal autonomy, self-awareness, and sexual experiences [1–7].

An important challenge to research on adolescent sexual health is lack of models that both integrate aspects of healthy sexual development and maintain attention on primary prevention of adverse sexual outcomes. Two widely cited definitions of sexual health are quoted in this issue: the World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as “…a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual responses, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.” [2]. A somewhat different definition of adolescent sexual health, endorsed by more than 50 national medical and policy organizations, is offered in the Consensus Statement of the National Commission on Adolescent Sexual Health (NCASH) [3]: “Sexual health encompasses sexual development and reproductive health, as well as such characteristics as the ability to develop and maintain meaningful interpersonal relationships; appreciate one’s own body; interact with both genders in respectful and appropriate ways; and express affection, love, and intimacy in ways consistent with one’s own values.” The Consensus Statement additionally notes that “responsible adolescent intimate relationships” should be “consensual, non-exploitative, honest, pleasurable, and protected against unintended pregnancy and STDs if any type of intercourse occurs.”

These definitions offer three important ideas to understanding how sexual health is organized in adolescents. The first of these ideas is that sexual health arises from a spectrum of different physical, social, emotional, and relationship experiences that occur as normative aspects of healthy sexual development [8,9]. For example, being in a romantic/sexual relationship during adolescence can afford a young person the opportunity to develop different skills, such as learning effective communication about one’s needs [10], negotiating conflict management [11], or successfully ending an unwanted relationship [12], which become necessary pieces in the management of adult sexuality. The second of these ideas, grounded in theories of growth and development, is that these normative experiences work collectively, rather than in isolation, to impact sexually related decisions [3,4,13]. In other words, this means that sexual health is greater than the sum of its individual parts, with each element contributing the influence of the whole. For example, relationship quality is positively linked to better communication about sex and contraception [14], and desiring a partner is positively associated with relationship satisfaction and commitment to partner [15]. Finally, the last of these ideas is that sexual health helps adolescents organize behavioral expressions of sexuality in ways that can include, as well as exclude, specific behavior choices. For example, although some studies describe how many adolescent relationships progress from “lighter” behaviors, such as hugging, kissing, hand holding, and oral sex [16,17], to more involved behaviors (e.g., vaginal sex) [18], other research suggests that some adolescents perceive sexual abstinence as an important expression of their sexuality [19].

To be truly useful from a clinical and public health perspective, scientific efforts to understand sexual health must operationalize concepts embedded in the definitions of sexual health using a range of dimensions related to healthy sexual development, and invoke an analytical method that permits an evaluation of the cumulative effect of these dimensions on a range of sexuality outcomes. However, to date, research has neither assessed the empirical coherence of sexual health as a multidimensional construct nor sought to understand its association to choices about different sexual behaviors, including abstinence. Therefore, using a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, the objectives of the current project were to (1) assess the empirical relationship of underlying dimensions to a larger construct of sexual health; (2) evaluate the overall stability and structural quality of this larger construct; (3) understand the influence of sexual health on sexual abstinence, noncoital and coital sexual behaviors, contraceptive use, condom use, and STI in adolescent women.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data were collected as part of a larger longitudinal cohort study of sexual relationships, sexual behaviors, and STIs among young women in middle to late adolescence (for a review of recruitment methods see [20]). Participants (N = 387; 90% Afri-can American) were adolescent women receiving health care as part of the patient population in one of three primary care adolescent health clinics in Indianapolis, IN. These clinics serve primarily lower- and middle-income families residing in areas with high rates of early childbearing and STI. The average maternal education level was 12th grade. Participants were eligible if they were 14–17 years of age, spoke English, and were not pregnant at enrollment. However, adolescent girls who became pregnant during the course of the study were permitted to continue. Sexual experience was not a criterion for entry.

As part of the larger study (initiated in 1999 and completed in 2009), young women participated in quarterly study visits for collection of interview and physical data related to the larger project. At enrollment and at each interview, participants identified up to five partners, including friends, dating partners, boyfriends, and sexual partners. As a means of examining various types and stages of relationships, partners were not limited to those with whom sexual behavior had happened. In each quarterly interview, young women provided partner-specific information related to relationship—emotional, behavioral, and sexual content. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University/ Purdue University at Indianapolis–Clarian, IN. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and permission was obtained from a parent or legal guardian.

For the current study, we used a subset of young women (N = 242; 62.5% of sample in larger study) who reported only one partner in their enrollment interview, who were not pregnant at enrollment, and whose complete sexual experience history data were available. Young women in this subset did not differ from those not selected on the basis of age (t = 1.876, p = .061), baseline STI status (t = −2.593, p = .591), having vaginal sexual experience (t = 1.511, p = .131), being a hormonal contraceptive user (t = .912, p = .364), and having oral sexual experience (fellatio: t = .109, p = .914; cunnilingus: t = .253, p = .800).

Model development

Analysis was initiated with the generation of a conceptual model based on definitions of sexual health as a means of specifying the relationships among the underlying dimensions of sexual health, the sexual health construct itself, and the relevant outcomes. We began by identifying four different areas—emotional, physical, mental/attitudinal, and social—emerging from the WHO [7] and NCASH [3] definitions of sexual health. As described earlier, for adolescents, these areas represent a range of normative developmental experiences working together to promote positive sexuality, which, in turn, is important for the expression of different sexually related behaviors. In this way, these experiences can be argued to underpin, or anchor, sexual health, which subsequently drives the organization of different outcomes.

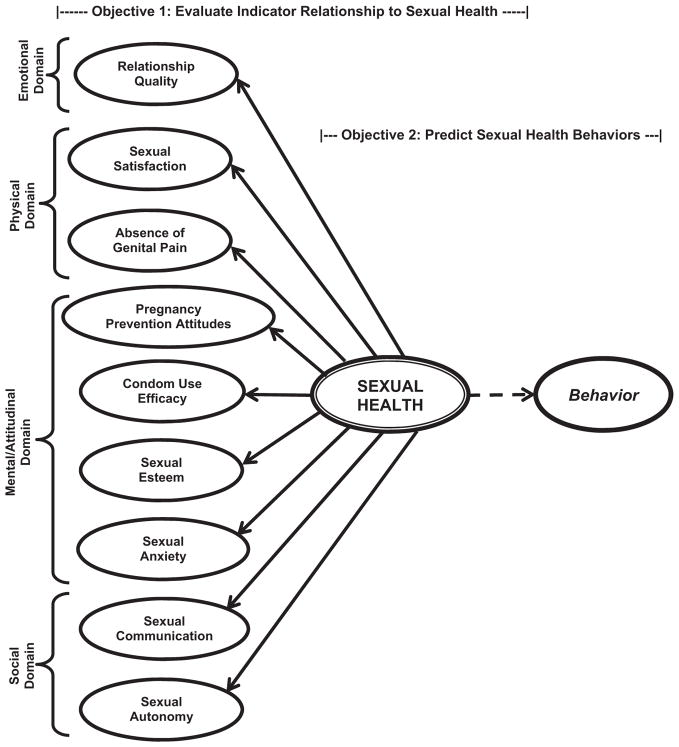

We then selected interview items that mapped onto these well-being—emotional, physical, mental/attitudinal, and social—areas, and which aligned with the substantive foci of the WHO and NCASH definitions. Next, we specified a working model, hypothesizing that these measures coalesce on sexual health to influence the outcomes of interest. Figure 1 illustrates these relationships. Domain-specific measures, their substantive foci, and descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 1; their measurement is described in more detail later in the text. The evaluation of alternative models is detailed in the Results section.

Figure 1.

Conceptual relationship: first-order latent variable sexual health indicators, second-order latent sexual health variable, and sexual behavior among adolescent women.

Note: Ovals represent latent variables (single line: first order; double line: second order); solid arrows represent the empirical relationship between sexual health indicators and sexual health (single model), and the dotted arrow represents the empirical relationship between sexual health and each outcome (separate models).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and measurement model indicator loadings for observed variables

| Sexual health variables | WHO definition domain/ substantive focus | Mean (SD) | Measurement model loadings (standardized) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship quality (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .92) | Emotional; PS | ||

| “I think I understand him/her as a person” | 3.15 (.81) | .802* | |

| “We have a strong emotional relationship” | 3.22 (.75) | .893* | |

| “We enjoy spending time together” | 3.30 (.66) | .896* | |

| “He/she is a very important person in my life” | 3.31 (.77) | .868* | |

| “I think I am in love with him/her” | 3.11 (.91) | .746* | |

| “I feel happy when we are together” | 3.26 (.71) | .895* | |

| Sexual communication (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .85) | Emotional; PR, PS | ||

| “It is easy to talk to him/her about sex” | 3.42 (.65) | .761* | |

| “It is easy to talk to him/her about condoms” | 3.44 (.62) | .843* | |

| “It is easy to talk to him/her about birth control” | 3.45 (.62) | .922* | |

| Sexual satisfaction (all 7 point: semantic differential; α = .93) | Physical; PR, PS | ||

| “Worthless to valuable” | 5.65 (1.75) | .831* | |

| “Very bad to very good” | 5.84 (1.53) | .911* | |

| “Very unpleasant to very pleasant” | 5.90 (1.49) | .937* | |

| “Very negative to very positive” | 5.72 (1.69) | .826* | |

| “Very unsatisfying to very satisfying” | 5.89 (1.56) | .926* | |

| Sexual autonomy (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .86) | Physical; FC | ||

| “It’s easy for me to say no if I don’t want to have sex” | 2.47 (.61) | .725* | |

| “Sometimes things just get out of control with him/her” (reverse coded for model) | 1.50 (.62) | .628* | |

| “It’s easy for him/her to take advantage of me” (reverse coded for model) | 1.48 (.58) | .915* | |

| Genital pain (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .83) | Physical; PS | ||

| “I almost always feel some pain after sexual intercourse” | 2.31 (.98) | .901* | |

| “It is painful if my partner touches my genital area” | 1.82 (.79) | .862* | |

| “I almost always feel some pain during sexual intercourse” | 2.36 (.99) | .762* | |

| “It is painful to use tampons” | .791* | ||

| “I experience pain during everyday activities” | .566* | ||

| Condom use efficacy (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .83) | Mental/attitudinal; PS | ||

| “It will be easy to use a condom/dental dam if we have sex” | 3.42 (.63) | .684* | |

| “He/she thinks condoms/dental dams are good for protection” | 3.85 (.71) | .805* | |

| “He/she thinks condoms/dental dams are easy to use” | 3.11 (.69) | .883* | |

| “He/she will have a condom/dental dam if we have sex” | 2.69 (.91) | .419* | |

| Fertility control (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .60) | Mental/attitudinal; PR, PS | ||

| “My partner wants me to get pregnant” (reverse coded) | 2.77 (.56) | .593* | |

| “I want to get pregnant” (reverse coded) | 2.90 (.37) | .938* | |

| “I am committed to not getting pregnant at this time” | 3.44 (.78) | .537* | |

| Sexual esteem (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .70) | Mental/attitudinal; PS | ||

| “My feelings about sexuality are an important part of who I am” | 2.51 (.85) | .999* | |

| “I really like my body” | 3.04 (.76) | .758* | |

| “I like the ways in which I express my sexuality” | 3.11 (.67) | .664* | |

| Sexual anxiety (all 4 point: strongly disagree to strongly agree; α = .85) | Mental/attitudinal; PS | ||

| “Sometimes in sexual situations I worry that things will get out of hand” | 1.77 (.76) | .827* | |

| “When I am in a sexual situation, I feel confused about what I want to happen” | 1.77 (.74) | .843* | |

| “I worry about being taken advantage of sexually” | 1.76 (.78) | .895* | |

| “In sexual situations, I am comfortable and sure about what to do” (reverse coded) | 2.07 (.75) | .782* | |

| “Sometimes it is difficult for me to relax in sexual situations” | 1.95 (.79) | .885* | |

| Sexual health outcomes | |||

| Sexual abstinence (yes) | — | .21 (.16) | |

| Used condom at last sex (yes) | — | .38 (.48) | — |

| Ratio of condom-protected events | — | .48 (.43) | — |

| Other fertility control method (withdrawal or rhythm: yes) | — | .23 (.43) | — |

| Current hormonal contraceptive user (yes) | — | .14 (.34) | — |

| Vaginal sex frequency (log) | — | 18.17 (30.13) | — |

| Noncoital sex frequency | — | 3.87 (1.95) | — |

PR = Positive and respectful approach to sexuality and relationships; PS = Pleasurable and safe sexual experiences; FC = Free from coercion, discrimination, and violence.

p < .001.

Measures

Sexual health domains

Emotional domain

Relationship quality included six, 4-point Likert-type items (strongly disagree [SD] to strongly agree [SA]; α = .94; e.g., “We have a strong emotional relationship”; used in previous research, e.g., [21]).

Physical domain

Sexual satisfaction was five, 7-point semantic differential items (α = .95) assessing a participant’s feelings about the sexual relationship with that partner (e.g., “very bad to very good”) [22]. Genital pain was assessed using five, 4-point items (SD to SA; α = .83; e.g., “it is painful if my partner touches my genital area”; developed for the larger study by the investigators).

Mental/attitudinal domain

Condom use efficacy was 4-point Likert items (SD to SA; α = .81; e.g., “it will be easy to use a condom/dental dam if we have sex). Pregnancy prevention attitudes (α = .81) was one individual 4-point item (SD to SA), “I am committed to not getting pregnant at this time in my life,” and two partner-specific items assessing reasons for sex (both 3-point: not at all important to very important [reverse recoded]), “I am trying to get pregnant” and “My partner wants me to get pregnant.” Sexual esteem was three, 4-point Likert items (SD to SA; α = .79; e.g., “My feelings about sexuality are an important part of who I am”). Sexual anxiety included five, 4-point Likert items (SA to SD; α = .85; e.g., “When I am in a sexual situation, I feel confused about what I want to happen”). Both sexual esteem and sexual anxiety have been used in previous research [23].

Social domain

Sexual communication was three, 4-point Likert items (SD to SA; α = .90; e.g., “It will be easy to talk to him/her about sex”). Sexual autonomy was three, 4-point items (SD to SA; α= .82; e.g., “It’s easy for me to say no if I don’t want to have sex”).

Sexual and prevention behaviors

Behavioral outcomes included sexual abstinence (absence of any vaginal and any anal intercourse: no/yes). Among those with any sexual experience, we also examined vaginal sex frequency, condom use at last sex (no/yes), ratio of condom-protected events, any hormonal pregnancy prevention method (no/yes), other pregnancy prevention method (withdrawal or the rhythm method: yes), noncoital sex frequency (additive index, all no/ yes: fellatio, cunnilingus, touching partner’s genitals, having one’s genitals touched, kissing). Finally, we also explored incidence of STI (past 3 months, any diagnosis of Chlamydia, gonor-rhea, or trichomoniasis).

Data analysis

SEM was the methodology used to evaluate the proposed model. SEM is a flexible methodology that allows researchers to examine several empirical relationships simultaneously while also assessing the factor structure of the items. In doing so, the analyses account for measurement error while estimating the significance of the paths between variables [24].

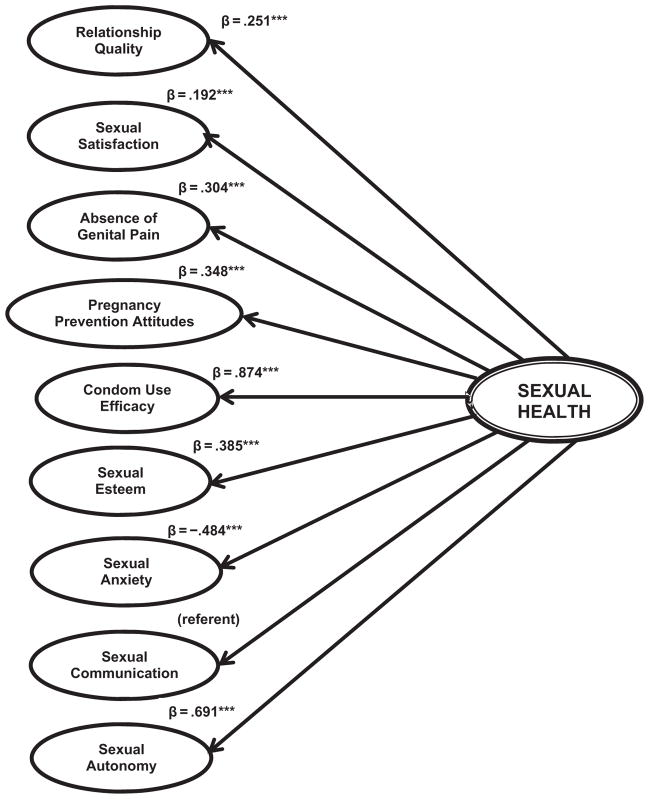

Objective 1 focused on assessing the empirical relationship between sexual health and its underlying dimensions. As suggested in the model development description, we hypothesized that different types of emotional, physical, social, and mental/ attitudinal experiences coalesce through sexual health to influ-ence behavior. In the language of SEM, this means that the observed (or measured) interview data become the empirical indicators, or structure, of the latent variable (or unobserved) experiences they are believed to represent. In turn, these latent variables become the empirical indicators of a secondary latent sexual health variable. After individually confirming the factor structure of each first-order latent variable and its observed data (Table 1), we linked all first-order latent variables to the secondary latent sexual health variable, evaluating the value and significance of each path using critical ratios (t > 1.96; p < .05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model estimates (standardized) relationship between first-order latent sexual health indicators and second-order sexual health variable among adolescent women (Objective 1). ***p < .001.

Note: Ovals represent latent variables [single line: first order; double line: second order]; solid arrows represent the empirical relationship between sexual health indicators and sexual health (single model).

Model fit indices: χ2 (df) = 1,212.66 (615)***; comparative fit index (CFI) = .907; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (90% confidence interval [CI]) = .068 (.058–.069).

Objective 2 centered on evaluating the structural integrity of sexual health as a multidimensional construct. After confirming the significance of each underlying dimension, we evaluated the overall fit of the model to the data as a means of gauging structural soundness. Overall goodness of fit was assessed using the chi-square statistic [25]; in general, nonsignificant values suggest that the model fits as well as the specified model. We also measured local goodness of fit with the comparative fit index (CFI), for which ideal values range between .90 and 1.0, as well as the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [26], for which values of .08 or below indicate reasonable fit of the model to the data.

Objective 3 centered on evaluating the association of sexual health to specific behavior outcomes, including sexual abstinence, noncoital and coital sexual behaviors, contraceptive use, condom use, and STI. To evaluate these relationships, we retained the model from the previous step, adding a path from sexual health to behavior [24]. Each outcome was assessed in a separate model to better isolate the influence of sexual health on each behavior, as well as to avoid biased estimates in the case where one outcome was mathematically related to another (e.g., condom use ratio was calculated using vaginal sex frequency in its denominator). We also assessed model fit using the aforementioned methods. All analyses were conducted in AMOS 17.0 (IBM Software, Inc., Armonk, NY), using full information maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Objectives 1 and 2. Assess the empirical relationship of underlying dimensions to sexual health, and evaluate the structural quality of sexual health as a larger construct

Preliminary versions of this model did not fit the data well; based on model modification indices, we added error term covariance between two error term pairs of sexual esteem measures, between three error term pairs of condom use efficacy measures, and between the error terms of the relationship quality and sexual satisfaction, as well as between the error terms of sexual esteem and sexual anxiety (not shown). No significant alternations to loading values occurred as a result of these modifications (Figure 2).

All first-order latent variables significantly loaded onto the second-order variable, suggesting that sexual health has signifi-cant underlying components. Specifically, higher sexual health was associated with higher relationship satisfaction (β = .251), higher sexual satisfaction (β = .192), greater absence of genital pain (β = .304), greater commitment to pregnancy prevention (β = .348), greater condom use efficacy (β = .874), higher sexual esteem (β = .385), lower sexual anxiety (β = −.484), and higher sexual autonomy (β = .691). No estimate was generated for sexual communication, as it was used as the referent in this model. In supplementary analyses, we also explored the predictive influence of age and race/ethnicity (African American/other) on sexual health; neither was significant (age: B = −.126, p = .067; race/ethnicity: B = .231, p = .127). Model fit indices (χ2 [df] = 1,212.66 [615]; p < .001; CFI = .907; RMSEA [90% confidence interval] = .068 [.058–.069]) demonstrated good fit of the model to the data, suggesting stable structure of sexual health as a larger construct.

Two different types of alternative models were also explored within this objective. First, to examine the possibility that other sexual health indicators not directly related to either sexual health definition were excluded, we compared the retained model with one including three additional latent factors on general preferred partner characteristics (physical traits, e.g., “cute face”; emotional traits, e.g., “treats me with respect”; social traits, e.g., “popular”), as well as one including two factors related to reasons for sex (extrinsic reasons, e.g., “for the thrill of it” and emotional reasons, e.g., “it makes me feel loved”). In both instances, global and local model fit indices declined, and none of the added factors was significant. Second, we examine the parsimony of smaller versions of the retained model, removing in turn all measures associated with a given domain (e.g., as part of the “physical” domain, we removed measures related to sexual satisfaction and sexual autonomy). In all comparisons, either no significant differences were noted in fit indices or the model failed to converge. In light of both alternatives, we retained the proposed model.

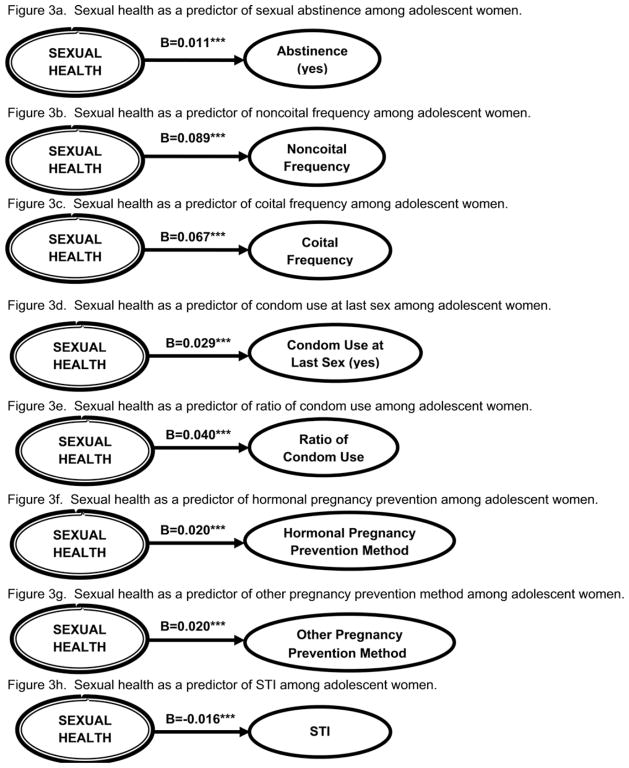

Objective 3: Understand the influence of sexual health on behavior

Retaining the model from the previous step, we tested sexual health as a predictor of behaviors. As shown in Figure 3, all outcomes were evaluated in separate models, with significant path values and good fit of the model to the data in each (Figure 3). Specifically, higher sexual health was associated with a greater likelihood of sexual abstinence (β = .011), more frequent noncoital sex (β = .089), more frequent vaginal sex (β = .067), condom use at last sex (β = .029), a higher condom use ratio (β = .04), use of hormonal pregnancy prevention methods (β = .020), use of other pregnancy prevention methods (β = .020), and absence of STI (β = −.016). All findings suggested good fit of the data to the models.

Figure 3.

Model estimates (standardized) relationship of second-order sexual health variable with sexual behaviors among adolescent women (Objective 3). ***p < .001.

Note: Ovals represent latent variables [double line: second order; solid line: outcomes]; solid arrows represent the empirical relationship between sexual health and behaviors.

Model fit indices (abstinence): χ2 (df) = 1,212.66 (615)***; CFI = .907; RMSEA (90% CI) = .068 (.058–.069).

Model fit indices (noncoital sex frequency): χ2 (df) = 1,125.19 (615)***; CFI = .901; RMSEA (90% CI) = .059 (.053–.064).

Model fit indices (vaginal sex frequency): χ2 (df) = 1,176.43 (615)***; CFI = .899; RMSEA (90% CI) = .061 (.055–.066).

Model fit indices (condom use at last sex): χ2 (df) = 1,090.45 (615)***; CFI = .902; RMSEA (90% CI) = .057 (.053–.062).

Model fit indices (ratio of condom use): χ2 (df) = 1,120 (615)***; CFI = .920; RMSEA (90% CI) = .058 (.053–.064).

Model fit indices (hormonal pregnancy prevention method): χ2 (df) = 1,072.83 (615)***; CFI = .904; RMSEA (90% CI) = .056 (.050–.061).

Model fit indices (other pregnancy prevention method): χ2 (df) = 1,382.71 (615)***; CFI = .880; RMSEA (90% CI) = .064 (.059–.068).

Model fit indices (sexually transmitted infections): χ2 (df) = 1,068.96 (615)***; CFI = .907; RMSEA (90% CI) = .058 (.054–.068).

Discussion

Sexual health has emerged as an important guiding paradigm in the developmental [27] and public health [1] literature as a means of promoting both positive sexual development and prevention of adverse health outcomes. Guided by two existing definitions [3,7], we used SEM to operationalize a multidimensional model of adolescent women’s sexual health. Our data demonstrate that sexual health is an empirically coherent structure, in which the totality of sexual-developmental dimensions is significantly linked to a wide range of behaviors, including sexual abstinence, frequency of non-coital and vaginal sex, condom use, hormonal methods of pregnancy prevention, and absence of STI.

From a developmental perspective, these data join an expanding understanding of how experiences during adolescence contribute to sexual development [28–30]. Parallel to past work [8,31], our results confirm that separate attitudes, beliefs, and evaluations all contribute to a core of sexual well-being during this time frame [32], with this core influencing sexual expression in different ways for different people. For example, separate studies have shown the importance of sexual health elements in explaining the inclusion of type, frequency, and function of sexual behaviors in sexually active adolescent relationships [11,18,33,34], as well as the exclusion of sexual behavior in sexually abstinent adolescent relationships [19,35]. However, a recent review [27] of positive sexual development challenges future research to move beyond this “either/or” dichotomy, and to better consider the influence of sexual health across a spectrum of sexual outcomes. Our findings answer this call, extending existing research to demonstrate that sexual health is jointly associated with sexual abstinence and sexual and prevention behaviors. This suggests that the collection of experiences and attitudes underlying sexual health is relevant in different ways across development, likely changing in meaning as young women’s sexual health is a relevant concept across different stages of development, even for sexual behaviors such as abstinence and penile–vaginal sex, which are often thought to be mutually exclusive.

The salience of sexual health across a number of behaviors is also relevant from a public health perspective. The recent implementation of sexual health as a framework for STI prevention in adolescents is a radical reorientation of public health perspective and effort. Our data provide empirical support for this reorientation by suggesting that at least two key STI-related indicators—sexual abstinence and condom use—can be accounted for by an underlying construct of sexual health. This means that a primary public health function—sentinel surveillance—could be implemented using measures that are reasonably easy to collect from diverse populations.

Finally, these data also support a greater emphasis on research strategies that systematically track developmentally relevant indicators of sexual health and associated behaviors [36,37]. Efforts to realign public health prevention and control efforts away from risk-based perspectives to a sexual health perspective have been hampered by a general lack of data [36]. The findings presented here provide insight as to what type of future work will guide the development and provision of sexual and reproductive services, professional training, and resource allocation [37]. For example, we suggested that satisfaction with sexual relationship is a meaningful element of sexual health and, by extension, is therefore a significant aspect of STI prevention through its association with sexual abstinence and condom use. Yet, the idea that young women can evaluate the sexual qualities of a relationship, and that evaluation affects STI risk, although plentiful in the developmental literature, is virtually unaddressed in the adolescent STI literature. Adolescent STI prevention that emphasizes elements of sexual health, such as sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and relationships, would possibly open a new era in public health approaches to prevention [38].

Several limitations should be considered. Other data are required to extend these analyses to more racially and geographically balanced samples of young women, and to samples of young men. Additionally, knowledge is lacking about the application of sexual health to adolescents with same-sex partners or those choosing both same- and different-sex partners. However, a public health infrastructure for obtaining diverse measures of sexual health from diverse adolescent samples does not currently exist. Substantial changes to nationally deployed surveys, such as the Youth Risk Behavior Survey or the National Survey of Family Growth, would be required to fully operationalize measures of sexual health, such as the survey we presented. Finally, models are cross-sectional and do not take into account what, if any, developmental changes occur in sexual health and what implications these changes have on sexual and prevention behaviors.

However, even within the context of these limitations, our analyses provide a strong hint that such data would profitably contribute to a new public health perspective on adolescents and STI. The technical capacity to incorporate a sexual health perspective into prevention of adolescent STI is also obvious. The necessary social and political will to adopt such a perspective seems much more problematic.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Sexual health generally refers to a state of well-being related to sexuality. Our results illustrate that young women’s sexual health positively influences a range of behaviors, including sexual abstinence. Regardless of a young person’s experiences, sexual health is an important construct for promoting positive sexual development and for primary prevention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NICHD grant R01 HD044387. The authors thank the staff of the Young Women’s Project, as well as the anonymous reviewers of this work.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this research was presented at the 2011 Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine Annual Meeting.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A public health approach for advancing sexual health in the United States: Rationale and options for implementation, meeting report of an external consultation. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. Cited March 28, 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/sexualhealth/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haffner DW. Facing facts: Sexual health for America’s adolescents. New York, NY: National Commission on Adolescent Sexual Health, Sexuality Information and Educational Council of the United States; 1995. p. 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan American Health Organization. Promotion of sexual health: Recommendations for action. Antigua Guatemala, Guatemala: Pan American Health Organization; 2000. Available at: http://www.paho.org/english/hcp/hca/promotionsexualhealth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The second decade: Improving adolescent health and development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Reproductive health strategy to accelerate progress towards the attainment of international development goals and targets. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. What constitutes sexual health? Progress in reproductive health research No 67. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolman DL, Striepe MI, Harmon T. Gender matters: Constructing a model of adolescent sexual health. J Sex Res. 2003;40:4–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teitelman AM, Bohinski JM, Boente A. The social context of sexual health and sexual risk for urban adolescent girls in the United States. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30:460–9. doi: 10.1080/01612840802641735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone N, Ingham R. Factors affecting British teenagers’ contraceptive use at first intercourse: The importance of partner communication. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. Affairs of the heart: Qualities of adolescent romantic relationships and sexual behavior. J Res Adolesc. 2010;20:983–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA, Flanigan CM. Developmental shifts in the character of romantic and sexual relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. In: Booth A, Brown SL, Landale NS, et al., editors. Early Adulthood in a Family Context. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 133–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Measuring sexual health: Conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widman L, Welsh DP, McNulty JK, Little KC. Sexual communication and contraceptive use in adolescent dating couples. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:893–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welsh DP, Haugen PT, Widman L, et al. Kissing is good: A developmental investigation of sexuality in adolescent romantic couples. Sex Res Social Policy. 2005;2:32–41. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2005.2.4.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein M, Calzo JP, Smiler AP, Ward LM. “Anything from making out to having sex”: Men’s negotiations of hooking up and friends with benefits scripts. J Sex Res. 2009;46:414–24. doi: 10.1080/00224490902775801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bay-Cheng LY, Robinson AD, Zucker AN. Behavioral and relational contexts of adolescent desire, wanting, and pleasure: Undergraduate women’s retrospective accounts. J Sex Res. 2009;46:511–24. doi: 10.1080/00224490902867871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Sullivan LF, Cheng MM, Harris KM, Brooks-Gunn J. I wanna hold your hand: The progression of social, romantic and sexual events in adolescent relationships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:100–7. doi: 10.1363/3910007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buhi ER, Goodson P, Neilands TB, Blunt H. Adolescent sexual abstinence: A test of an integrative theoretical framework. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38:63–79. doi: 10.1177/1090198110375036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fortenberry JD, Temkit MH, Tu W, et al. Daily mood, partner support, sexual interest, and sexual activity among adolescent women. Health Psychol. 2005;24:252–7. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayegh MA, Fortenberry JD, Anderson JG, Orr DP. Effects of relationship quality on chlamydia infection among adolescent women. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:163e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrance K-A, Byers ES. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relat. 1995;2:267–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD, O’Sullivan LF, Orr DP. The developmental association of sexual self-concept with sexual behavior among adolescent women. J Adolesc. 2011;34:675–84. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis/Routledge Academic; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 136–62. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21:242–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00726.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Impett EA, Tolman DL. Late adolescent girls’ sexual experiences and sexual satisfaction. J Adolesc Res. 2006;21:628–46. doi: 10.1177/0743558406293964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diamond LM. Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Sullivan LF, Majerovich J. Difficulties with sexual functioning in a sample of male and female late adolescent and young adult university students. Can J Hum Sex. 2008;17:109–21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Sullivan LF. The social and relationship contexts and cognitions associated with romantic and sexual experiences of early-adolescent girls. Sex Res Social Policy. 2005;2:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Ducat WH, Boislard-Pepin MA. A prospective study of young females’ sexual subjectivity: Associations with age, sexual behavior, and dating. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:927–38. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning WD, Flanigan CM, Giordano PC, Longmore MA. Relationship dynamics and consistency of condom use among adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41:181–90. doi: 10.1363/4118109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manning WD, Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Hocevar A. Romantic relationships and academic/career trajectories in emerging adulthood. In: Fincham FD, Cui M, editors. Romantic Relationships in Emerging Adulthood. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011. pp. 317–33. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbott DA, Dalla RL. “It’s a choice, simple as that”: Youth reasoning for sexual abstinence or activity. J Youth Stud. 2008;11:629–49. doi: 10.1080/13676260802225751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halpern CT. Reframing research on adolescent sexuality: Healthy sexual development as part of the life course. (Sexual and reproductive health: Priorities for the next decade) (report) Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42(2):6–7. doi: 10.1363/4200610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fenton KA. Time for change: Rethinking and reframing sexual health in the United States. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):250–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philpott A, Knerr W, Maher D. Promoting protection and pleasure: Amplifying the effectiveness of barriers against sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy. Lancet. 2006;368:2028–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]