SUMMARY

Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction requires direct binding of β-catenin to Tcf/Lef proteins, an event that is classically associated with stimulating transcription by recruiting coactivators. This molecular cascade plays critical roles throughout embryonic development and normal postnatal life by affecting stem cell characteristics and tumor formation. Here, we show that this pathway utilizes a fundamentally different mechanism to regulate Tcf7l1 (formerly named Tcf3) activity. β-catenin inactivates Tcf7l1 without a switch to a coactivator complex by removing it from DNA, which leads to Tcf7l1 protein degradation. Mouse genetic experiments demonstrate that Tcf7l1 inactivation is the only required effect of the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction. Given the expression of Tcf7l1 in pluripotent embryonic and adult stem cells, as well as in poorly differentiated breast cancer, these findings provide mechanistic insights into the regulation of pluripotency and the role of Wnt/β-catenin in breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling impacts a wide range of biological activities, including stem cell self-renewal, organ morphogenesis, and tumor formation (Clevers and Nusse, 2012; Nusse, 2012). Regulation of the pathway centers on the stability of β-catenin, which is targeted for proteasome-mediated degradation by a complex containing adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Axin structural proteins, and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) (Stamos and Weis, 2013). Phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3 stimulates degradation dependent upon APC, Axin, and the β-TrCP E3 ligase (Aberle et al., 1997; Hart et al., 1999; Yost et al., 1996). Wnt signaling inhibits degradation of β-catenin by blocking its ubiquitination (Li et al., 2012). Pharmacological GSK3 inhibitors similarly inhibit β-catenin degradation by blocking β-catenin phosphorylation.

An important downstream mechanism of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway occurs as β-catenin binds to the amino terminal of Tcf/Lef proteins, thereby displacing corepressor proteins bound to the Tcf/Lef (Cavallo et al., 1998; Daniels and Weis, 2005; Roose et al., 1998). Tcf-β-catenin binding subsequently recruits transactivator proteins to the genomic sites that were previously occupied by corepressors (Brannon et al., 1997; Molenaar et al., 1996; van de Wetering et al., 1997). This accepted model of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is consistent with observed effects of Tcf/Lef proteins in many contexts (Cadigan and Waterman, 2012); however, it is not consistent with recent observations for mammalian Tcf7l1 (formerly Tcf3). In cells where Lef1 and Tcf7 (formerly Tcf1) act as β-catenin-dependent transactivators, only transcriptional repressor activity for Tcf7l1 was detected (Merrill et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2012a). Here, we show that β-catenin binding to Tcf7l1 does not form a transactivation complex, but instead initiates a fundamentally distinct mechanism. β-catenin binding inactivates Tcf7l1 by reducing its chromatin occupancy and secondarily stimulates its protein degradation. Mouse genetic experiments demonstrate that this inactivation is the only necessary function of the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction. These molecular and genetic findings provide insights into the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cells where Tcf7l1 expression is prominent, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and poorly differentiated breast cancer.

RESULTS

β-Catenin Reduces Tcf7l1 Protein Levels by Stimulating Protein Degradation

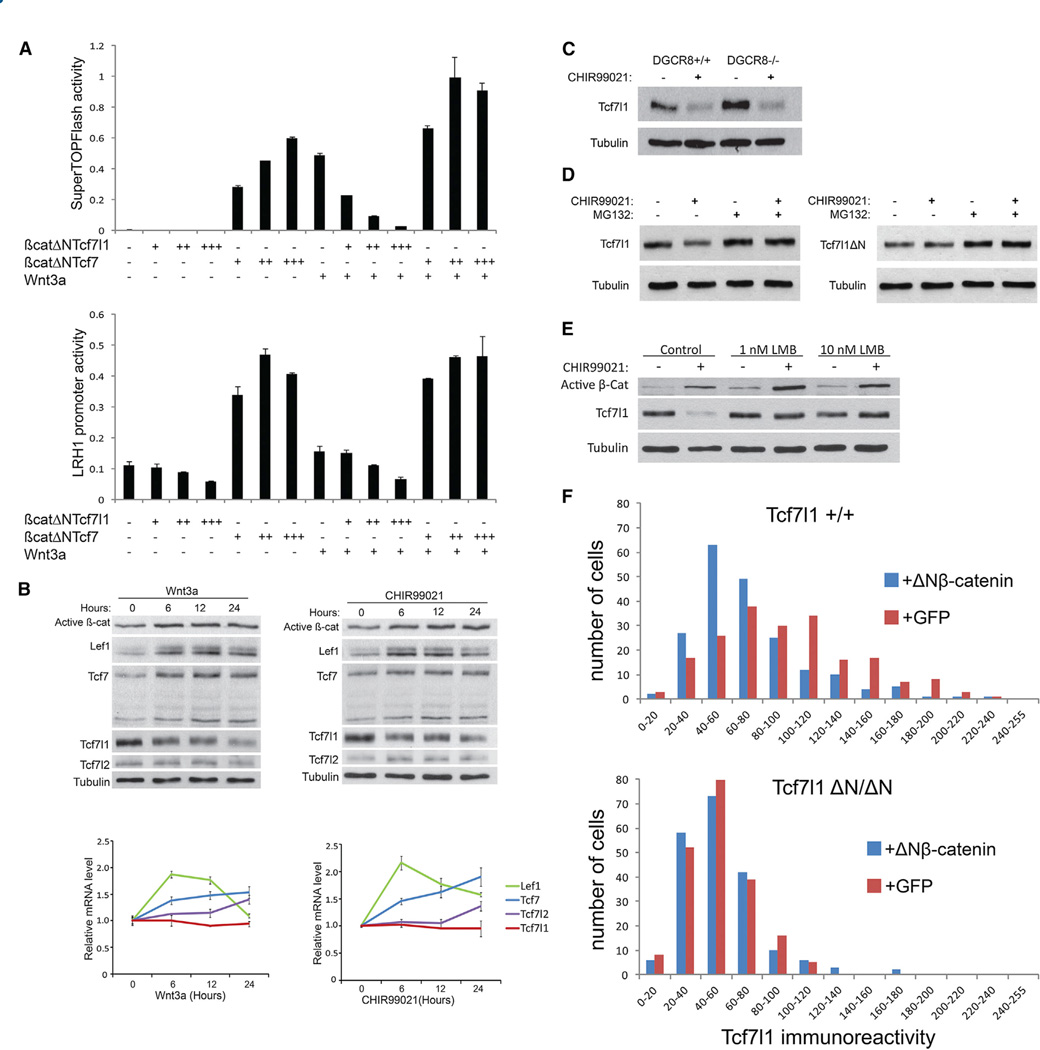

Molecular support for a conversion into transactivators by β-catenin includes the ability of a β-catenin-Tcf7 fusion protein to activate target genes without Wnt pathway stimulation (Staal et al., 1999). If Tcf7l1 were switched to a transactivator by β-catenin, one would expect a β-catenin-Tcf7l1 fusion protein to similarly activate target genes. In ESCs, the β-catenin-Tcf7l1 fusion was unable to activate TOPFlash and LRH-1 reporters, and instead repressed Wnt3a-stimulation of reporter genes (Figure 1A). Rather than converting Tcf7l1 to a transactivator, Wnt/β-catenin stimulation notably decreased Tcf7l1 protein in ESCs treated with recombinant Wnt3a or the GSK3 inhibitor, Chiron99021 (CHIR; Figure 1B). These results indicate a significant difference in the downstream effects of Tcf7-β-catenin and Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction.

Figure 1. Wnt/β-Catenin Stimulates Tcf7l1 Protein Degradation.

(A) Transient transfection of Tcf7l1−/− ESCs with β-catenin-Tcf fusion plasmids and SuperTOPFlash (top) or LRH1 promoter (bottom) luciferase reporter plasmids. Values represent mean ± SD for triplicate transfections.

(B) Western blot (top) and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR, bottom) analyses of ESCs treated with 50 ng/ml recombinant Wnt3a (left) or 3 µM CHIR (right). Values represent mean ± SD for biological triplicates.

(C–E) Western blot analysis of ESCs treated with 3 µM CHIR for 24 hr in Dgcr8 mutant cells (C), for 6 hr with MG-132 (5 µM) in Tcf7l1+/+ and Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN cells (D), and for 12 hr with leptomycin B (E).

(F) Distribution of nuclear Tcf7l1 immunoreactivity levels in Tcf7l1+/+ (top) and Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN (bottom) cells expressing either GFP (red bars) or ΔNβ-catenin (blue bars). A total of 200 nuclei were counted for each condition. Data are representative of three separate experiments.

See also Figure S1.

To elucidate the transactivation-independent effects of β-catenin on Tcf7l1, we investigated how Tcf7l1 protein levels were reduced. Wnt3a- and CHIR-treated ESCs displayed increased Lef1 and Tcf7 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels that correlated with increased protein levels (Figure 1B), consistent with Lef1 and Tcf7 being Wnt/β-catenin target genes (Filali et al., 2002; Hovanes et al., 2000; Roose et al., 1999; Waterman, 2004). In contrast, decreased Tcf7l1 protein was not paralleled by a significant change in mRNA levels (Figure 1B), indicating that β-cate-nin regulation of Tcf7l1 does not occur transcriptionally. Because Dgcr8 is a required component of the microprocessor complex, which is necessary for biogenesis of microRNAs (Wang et al., 2007), the CHIR-stimulated reduction of Tcf7l1 in Dgcr8−/− ESCs showed that reduction of Tcf7l1 protein was also not microRNA mediated (Figure 1C). Treatments with the proteasome inhibitors MG-132 and MG-115 effectively blocked the CHIR-stimulated reduction of Tcf7l1 protein (Figures 1D and S1A), demonstrating that reduction of Tcf7l1 required protein degradation. Finally, reduction of Tcf7l1 was blocked by leptomycin B, indicating that it required Exportin1-mediated nuclear transport (Figure 1E).

To determine the role of β-catenin binding to Tcf7l1, we used Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN knockin ESCs. In contrast to wild-type Tcf7l1, Tcf7l1ΔN was not degraded in response to CHIR or Wnt3a (Figures 1D and S1B), indicating that the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction was necessary for degradation. To determine whether the interaction was sufficient for degradation, we expressed ΔNβ-catenin in ESCs and measured the Tcf7l1 levels by quantitative immunofluorescence. ΔNβ-catenin expression was sufficient to reduce nuclear Tcf7l1 levels in Tcf7l1+/+ but not in Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN cells (Figures 1F and S1C). Interestingly, several recent studies showed that a mutant form of β-catenin (β-cateninΔC) supported self-renewal of mouse ESCs and complemented defects caused by ablation of β-catenin despite the lack of the C-terminal transactivation domain in the β-cateninΔC mutant (Kelly et al., 2011; Lyashenko et al., 2011; Wray et al., 2011). Therefore, it is notable that expression of ΔNβ-cateninΔC was also sufficient to reduce nuclear Tcf7l1 protein levels ESCs (Figure S1D). Given the substantial effects of altering Tcf7l1 levels in ESCs, the reduction of Tcf7l1 protein provides a mechanism for the poorly understood pro-self-renewal effects of β-cateninΔC in ESCs.

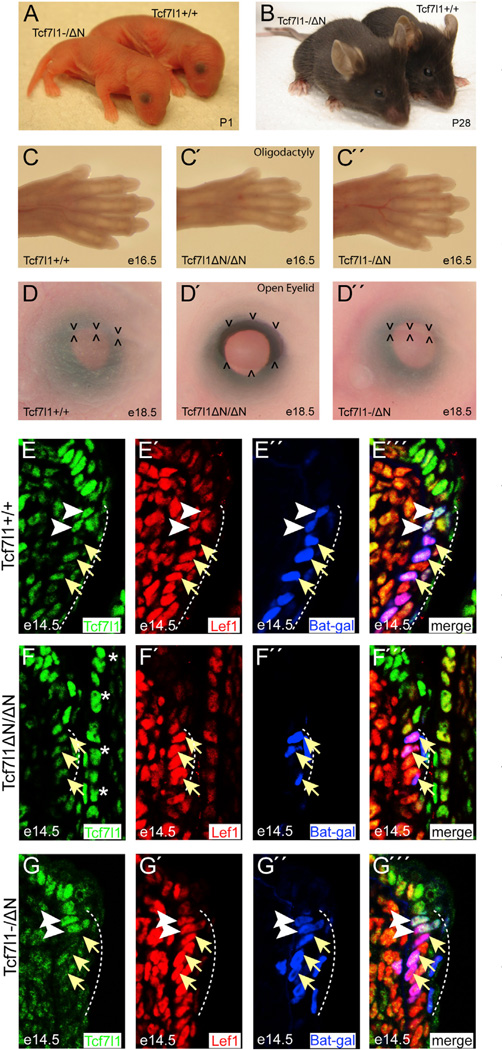

Reduction of Tcf7l1 Is Sufficient to Replace the Tcf7l1-β-Catenin Interaction

If a principal mechanism of Wnt/β-catenin signaling functions through inactivation of Tcf7l1, and not conversion to a Tcf7l1-β-catenin transactivator complex, reducing the level of Tcf7l1 should be sufficient to replace the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction. We first tested this hypothesis in ESCs, where reducing the amount of Tcf7l1ΔN by small interfering RNA(siRNA) stimulated the reporter gene response to Wnt3a (Figures S2A and S2B). To examine the broader effects of reducing Tcf7l1 in mice, we reduced the level of Tcf7l1 by breeding for hemizygous mice (i.e., Tcf7l1+/− or Tcf7l1−/ΔN; Figure S2C). It is important to note that Tcf7l1−/− mice die shortly after gastrulation (Merrill et al., 2004). Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN embryos progress normally through gastrulation, but later develop a constellation of morphogenetic defects that result in death for all Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN mice at or before birth (Hoffman et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2012a). Mating Tcf7l1+/− with Tcf7l1+/ΔN mice produced the Mendelian-expected ratio of Tcf7l1−/ΔN offspring, despite the genetic absence of a Tcf7l1 protein capable of interacting with β-catenin (Figures 2A and S2D). Moreover, Tcf7l1−/ΔN mice did not display any of the morphogenetic defects observed in Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN mice, including poor vascular integrity, edema, oligodactyly, and opened eyelids (Figures 2C–2D”, S2E, and S2F). Indeed, Tcf7l1−/ΔN mice advanced to adulthood and appeared indistinguishable from Tcf7l1+/+ littermates throughout their ostensibly normal lifetimes (Figure 2B). Thus, removing one copy of Tcf7l1ΔN genetically rescued the defects caused by ablating the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction. These results demonstrate that inactivation of Tcf7l1 by β-catenin is the necessary effect downstream of Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction for mouse embryogenesis and postnatal viability.

Figure 2. Reducing Tcf7l1 Levels Replaces the Requirement for β-Catenin Interaction in Mice.

(A-D″) Tcf7l1—/ΔN mice appear normal at birth (A) and through adult stages (B; see also Figure S2D). Tcf7l1—/ΔN embryos do not develop the phenotypes observed in Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN embryos (i.e., oligodactyly [C–C″] and opened eyelids at birth [D–D″]; see also Figures S2E and S2F).

(E–G″′) Tcf/Lef-β-catenin activation of BAT-Gal reporter is restored in the Tcf7l1—/ΔN eyelid. Immunofluorescent staining for Tcf7l1 (green), Lef1 (red), and β-galactosidase(blue) in e14.5 eyelids from BAT-Gal transgenics with the indicated Tcf7l1 genotype. Arrows point to Lef1-high and Tcf7l1-low nuclei.

Arrowheads point to Lef1-high and Tcf7l1-positive nuclei. The dotted line denotes the BAT-Gal-positive region. Asterisks mark Tcf7l1-positive cells in the nearby cornea.

To determine the effects of reducing Tcf7l1 at the target gene level in mice, tissues that were previously shown to be affected in Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN embryos were examined in Tcf7l1−/ΔN embryos harboring the BAT-Gal reporter. Compared with Tcf7l1+/+ embryonic day 14.5 (e14.5) eyelids (Figures 2E–E″′), Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN displayed a restricted domain of BAT-Gal activity and decreased expression of Lef1, a Wnt/β-catenin target, in the mucocutaneous junction of the eyelid (Figures 2F–2F″′; Wu et al., 2012a). The domain of Lef1 expression and BAT-Gal activity was increased in Tcf7l1−/ΔN relative to Tcf7l1ΔN/ΔN, and BAT-Gal activity was detected only in cells expressing Lef1 (Figures 2F–2G″′, S2G, and S2H). Given the inability of Tcf7l1ΔN to respond to β-catenin, the rescue of BAT-Gal activity in Tcf7l1−/ΔN embryos shows that activation is mediated by Lef1, and attenuation of this activation depends on the level of Tcf7l1 repressor.

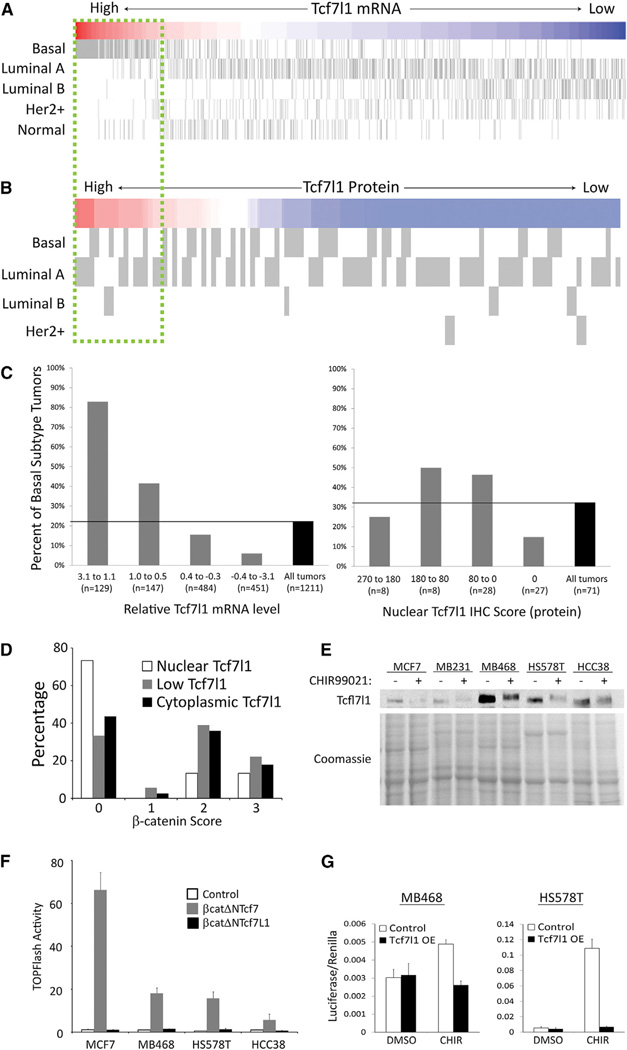

β-Catenin Stimulates TCF7L1 Inactivation in Human Breast Cancer

In addition to pluripotent cells in the early mammalian embryo, and ESCs in vitro, TCF7L1 mRNA expression has been noted in several types of adult stem cells and in poorly differentiated cancers (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Ivanova et al., 2002; Tumbar et al., 2004). We reasoned that the aspects of the Tcf7l1-destabilization mechanism could provide insights into the effects of Wnt/β-catenin in these important contexts. Breast cancer was chosen for further analysis because (1) Wnt/β-catenin has been known to affect mammary tumors since it was first discovered by Nusse et al. (1984), (2) despite its long history, the underlying mechanisms of Wnt/β-catenin’s effects in this disease remain poorly understood (Alexander et al., 2012), (3) poorly differentiated mammary tumors express high levels of TCF7L1 mRNA (0.81 mean TCF7L1 mRNA ± 0.91 SD for 270 basal tumors, −0.32 ± 0.67 for 941 nonbasal tumors; p < 0.0001; Figure 3A; Ben-Porath et al., 2008), and (4) altering the level of Tcf7l1 caused significant effects in xenograft tumor-formation experiments (Slyper et al., 2012).

Figure 3. Wnt/β-Catenin Inactivates TCF7L1 Protein in Poorly Differentiated Breast Cancer.

(A) Heatmap showing relative TCF7L1 mRNA levels and tumor subtype status from a compendium of 1,211 mammary tumors. Subtypes are displayed according to previous designations (Ben-Porath et al., 2008).

(B) Heatmap showing relative TCF7L1 protein nuclear immunoreactivity for all invasive tumors in an array of samples from 71 individual patients. Subtypes are displayed as determined previously (Khramtsov et al., 2010).

(C) Graphs show the distribution of basal subtype with respect to the level of TCF7L1 mRNA (left) or nuclear TCF7L1 protein (right).

(D) Distribution of tumors with nuclear TCF7L1 (n = 15, white), diffuse TCF7L1 (n = 38, black), or low TCF7L1 (n = 18, gray) classification relative to the IHC score for cytoplasmic β-catenin for each individual tumor. Values represent the percentage of tumors for each TCF7L1 classification displaying the indicated cytoplasmic β-catenin IHC score.

(E) TCF7L1 protein (western) and total protein (Coomassie) for human breast cancer cell lines treated with vehicle (DMSO) or CHIR (3 µM) for 12 hr.

(F and G) SuperTOPFlash luciferase reporter activity for breast cancer cell lines transiently transfected with the indicated β-catenin-Tcf fusion plasmid, wild-type Tcf7l1 plasmid, or empty vector. Values represent mean ± SD of technical duplicates of biological duplicates.

See also Figure S3.

Consistent with previous analyses, we noted a very high frequency of the basal molecular subtype among invasive mammary tumors expressing the highest levels of TCF7L1 mRNA (83% of tumors with TCF7L1mRNA > 1.1 were basal, and 22% of all tumors assessed were basal; Figure 3A; Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Slyper et al., 2012). To examine patterns of TCF7L1 protein expression, we used a TCF7L1-specific antibody for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of an array of breast cancer tissue samples (Figure S3A; Khramtsov et al., 2010). In contrast to TCF7L1 mRNA, nuclear TCF7L1 protein was not significantly higher in basal subtype tumors (55 ± 60, n = 23) relative to nonbasal tumors (44 ± 74, n = 47; Figures 3B and S3A), and the frequency of basal tumors displaying strong nuclear TCF7L1 (i.e., nuclear IHC score > 180) was lower than the overall frequency of basal tumors on the array (25% with high nuclear TCF7L1 versus 32% of all tumors; Figures 3C, S3B, and S3C). Thus, although TCF7L1 mRNA is highly elevated in basal subtype tumors, TCF7L1 protein is not.

Previous analyses of β-catenin protein in patient samples demonstrated that nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin was strongly associated with basal subtype tumors and poor prognosis (Geyer et al., 2011; Khramtsov et al., 2010; Lόpez-Knowles et al., 2010). To determine whether the disparity between TCF7L1 mRNA and protein levels could be caused by elevated β-catenin, we compared the TCF7L1 IHC results with the β-catenin IHC results among identical patient samples. Remarkably, tumors with strong nuclear TCF7L1 had predominantly no nuclear or cytoplasmic β-catenin (β-catenin IHC score of 0; Figure 3D), and tumors with cytoplasmic and/or nuclear β-catenin (β-catenin IHC score of 2 or 3) displayed predominantly diffuse or low levels of TCF7L1 protein (Figure 3D). These data indicate that in human mammary tumors, stimulation of Wnt/β-catenin is strongly correlated with decreased nuclear TCF7L1.

To test for a causal relationship between β-catenin and TCF7L1 levels in breast cancer, we used several cancer cell lines. Endogenous TCF7L1 protein was reduced by CHIR in all cells examined (MCF7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, HS578T, and HCC38; Figure 3E). As in the ESCs, TCF7L1 mRNA was not significantly diminished (Figure S3E), and the reduction of TCF7L1protein was blocked by the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Figure S3F). Treating cells with CHIR or CHIR + MG-132 increased the cytoplasmic levels of TCF7L1 detected by immunofluorescence (Figure S3G). As in the ESCs, Tcf7 was endogenously expressed and stimulated TOPFlash activity (Figures 3F and S3H), whereas overexpression of Tcf7l1 or β-catenin-Tcf7l1 fusion repressed TOPFlash activity (Figures 3F and 3G). Repression by Tcf7l1ΔN and Tcf7l1 HMG* mutants indicated that inhibition of TOPFlash was caused by a combination of β-catenin-binding- and DNA-binding-dependent activities of Tcf7l1 (Figure S3I). These results suggest that the mechanism of β-catenin-mediated inactivation of Tcf7l1 that was previously observed in ESCs and mouse embryos also occurs in human breast cancer.

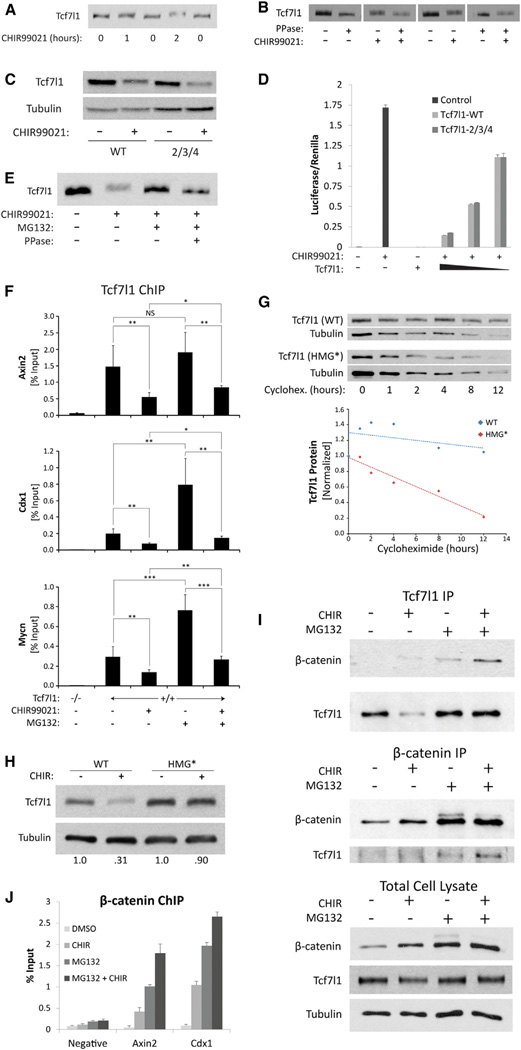

Tcf7l1 Inactivation Occurs Independently of Phosphorylation by HIPK2 or NLK

Treating human breast cancer cells with CHIR caused a substantial shift in the mobility of TCF7L1 as analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 3E). Although it is more difficult to detect in mouse ESCs, likely because of the multiple Tcf7l1 isoforms expressed in ESCs (Salomonis et al., 2010), this shift also affected endogenous Tcf7l1 in mouse ESCs treated with CHIR or Wnt3a (Figures 4A, 4B, and S4). Interestingly, work in other systems demonstrated mobility shifts caused by β-catenin-dependent phosphorylation of Tcf7l1/Tcf3 proteins by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HipK2) (Hikasa et al., 2010; Hikasa and Sokol, 2011) and nemo-like kinase (NLK) (Ishitani et al., 1999, 2003). In particular, HipK2 has been proposed to serve as a primary mediator of Tcf7l1 regulation by reducing chromatin binding after phosphorylation at conserved residues (Hikasa et al., 2010; Hikasa and Sokol, 2011). We previously showed that Tcf7l1 chromatin occupancy is reduced in ESCs by Wnt3a, and the reduction required the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction (Wu et al., 2012a). Therefore, we tested whether phosphorylation of Tcf7l1 at conserved residues was needed for inactivation by using the Tcf7l1-P2/3/4 mutant, which harbors mutations at the residues phosphorylated by HipK2 and NLK (Hikasa et al., 2010). Surprisingly, the Tcf7l1-P2/3/4 mutation did not affect CHIR-induced degradation of Tcf7l1 or Tcf7l1 repression of target gene expression in ESCs (Figures 4C and 4D). Thus, it is unlikely that Wnt/β-catenin inactivation of Tcf7l1 in ESC requires phosphorylation by HipK2 or NLK. In addition, although Tcf7l1 was indeed phosphorylated, we detected no change in phosphorylation in the absence or presence of CHIR stimulation. The CHIR-induced mobility shift of Tcf7l1 was not phosphatase sensitive, suggesting that it was not mediated by increased phosphorylation (Figure 4B). The nature of this posttranslational modification is not known; however, it was blocked by MG-132 (Figure 4E), indicating that it required an active proteasome.

Figure 4. Inhibition of Chromatin Occupancy Is Upstream of Tcf7l1 Protein Degradation.

(A and B) Western blot analysis of Tcf7l1 protein from ESCs.

(A) Cells were treated with 15 µM CHIR for 0–2 hr.

(B) Cells were treated with 3 µM CHIR for 12 hr and lysates were treated with 15 U/µL lambda phosphatase.

(C) Tcf7l1 protein from Tcf7l1−/− ESC stably expressing either Tcf7l1-wild-type (Tcf7l1-WT) or Tcf7l1-2/3/4. Cells were treated with 6 µM CHIR for 18 hr.

(D) SuperTOPFlash assay using Tcf7l1−/− ESC transiently transfected with either Tcf7l1-WT or Tcf7l1-2/3/4. Cells were treated with 3 µM CHIR for 12 hr. Values represent mean ± SD of technical duplicates of biological duplicates.

(E) Tcf7l1 protein from lysates of Tcf7l1−/− ESC stably expressing wild-type Tcf7l1. Cells were treated with 3 µM CHIR and 5 µM MG-132 for 12 hr. Lysates were treated with 15 U/µL lambda phosphatase.

(F) Quantitative ChIP using anti-Tcf7l1 antibody. Mouse ESCs were treated for 12 hr with 3 µM CHIR and/or 5 µM MG-132. qPCR measurements of Tcf7l1-bound DNA are shown for regions near Axin2, Cdx1, and Mycn genes. Values represent the mean + SD of percent of precipitated DNA relative to input for duplicate technical measurements of five biological replicates.**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; NS, p > 0.05.

(G) Top: Tcf7l1 and Tubulin proteins from lysates of Tcf7l1−/− ESC stably expressing either wild-type Tcf7l1 (WT) or the mutant Tcf7l1 HMG* (HMG*) protein. Cells were treated with 30 µg/ml cycloheximide. Bottom: quantitation of western blot and normalization of Tcf7l1 protein levels was calculated for WT (blue) and HMG* (red) proteins. Each data point represents the mean of biological triplicates.

(H) Western blot analysis comparing the CHIR-mediated reduction WT and HMG* Tcf7l1 proteins using the same ESCs as in (G).

(I) CoIP experiments using anti-Tcf7l1 (top) or anti-β-catenin (middle). Protein was immunoprecipitated from lysates of cells treated with 3 µM CHIR and 5µM MG-132 (bottom).

(J) Quantitative ChIP using anti-β-catenin antibody. Chromatin was isolated from ESCs treated for 12 hr with 3 µM CHIR and 5 µM MG-132. qPCR measurements of β-catenin-bound DNA are shown for regions near Axin2 and Cdx1 genes. Values represent the mean + SD of percent of precipitated DNA relative to input for duplicate technical measurements of three biological replicates.

See also Figure S4.

Reduction of Chromatin Occupancy Provides the Critical Upstream Point of Tcf7l1 Regulation

To elucidate how the reduction of chromatin occupancy is causally linked to protein degradation, we conducted quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments to measure Tcf7l1 chromatin occupancy following the combined CHIR + MG-132 treatment. As expected from the changes in Tcf7l1 protein levels (Figure 1B), CHIR reduced Tcf7l1 occupancy on target genes (Axin2, Cdx1, and Mycn), and MG-132 increased occupancy (Figure 4F). Importantly, CHIR treatment reduced chromatin occupancy even when destabilization of Tcf7l1 was blocked by MG-132 (Figure 4F), indicating the reduction in DNA binding was upstream of degradation. Interestingly, since MG-132 prevented the mobility shift of Tcf7l1 (Figure 4E), this result also indicates that the reduction of chromatin binding does not require the posttranslational modification. Combined with the increased cytoplasmic Tcf7l1 staining after CHIR + MG-132 treatment (Figure S3G), these data indicate that Tcf7l1 is likely degraded after export from the nucleus.

To examine the role of chromatin occupancy in regulating Tcf7l1 stability, we used the Tcf7l1 HMG* mutation, which affects the DNA-binding HMG domain and disrupts DNA binding (Merrill et al., 2001). The HMG* mutation was sufficient to reduce Tcf7l1 protein stability in the absence of CHIR (Figure 4G). Moreover, stability of the mutant Tcf7l1 HMG* protein was not substantially decreased by CHIR (Figure 4H), indicating that destabilization of Tcf7l1 requires a change in chromatin occupancy. In support of the model focused on reduction of chromatin occupancy, coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) experiments showed that Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction was stimulated by CHIR + MG-132 (Figure 4I), and β-catenin chromatin occupancy increased (Figure 4J) while Tcf7l1 occupancy decreased (Figure 4F). Together, these data are most consistent with the notion that the primary effect of the Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction is to inhibit chromatin occupancy. The secondary effect of Tcf7l1 degradation provides an additional mechanism by lowering Tcf7l1 levels, which further reduces the amount of Tcf7l1 available to bind to chromatin. Thus, the combination of reduced DNA binding and Tcf7l1 degradation leads to an additive reduction of Tcf7l1 repression in response to Wnt/β-catenin activity.

DISCUSSION

The molecular effects of Wnt/β-catenin and Gsk3 inhibition on Tcf7l1 described here indicate that Tcf7l1 primarily functions outside of the classic model of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In ESCs, inactivation of Tcf7l1 did not require phosphorylation of Tcf7l1 at conserved sites, and β-catenin was sufficient to reduce Tcf7l1 levels without exogenous pathway stimulation. These results are consistent with a mechanism of inactivation wherein β-catenin binding inhibits Tcf7l1-repression by reducing chromatin occupancy, consequently stimulating its degradation. This mechanism provides a simple explanation for the controversial pro-self-renewal effects of the β-cateninΔC mutant in ESCs (Kelly et al., 2011; Lyashenko et al., 2011; Wray et al., 2011): the critical effect of inactivating Tcf7l1 is stimulated by the β-cateninΔC form, thus making β-catenin’s C-terminal transactivation domain dispensable in ESCs.

Together, the results from experiments using human breast cancer tumors, breast cancer cell lines, and mouse genetics indicate that inactivation of Tcf7l1 is the predominant mechanism whereby Wnt/β-catenin signaling interacts with this mammalian Tcf/Lef protein. The viability of Tcf7l1−/ΔN mice genetically demonstrates that inactivation of Tcf7l1 is the only effect of Tcf7l1-β-catenin binding that is required for normal mouse development and life. That said, additional activities downstream of Tcf7l1-β-catenin interaction likely exist. Indeed, reporter gene assays support rare Tcf7l1-β-catenin transactivator activity in some cell types (e.g., 293T, COS7, and human keratinocytes; Merrill et al., 2001; Slyper et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012a); however, the biological significance of this effect remains to be determined.

Human breast cancer is one important context in which Tcf7l1-based activation has been suggested (Slyper et al., 2012). Basal subtype tumors are particularly relevant because they have been noted to share a gene-expression signature with ESCs (Ben-Porath et al., 2008) and fetal mammary stem cells (Spike et al., 2012). These tumors, which express high levels of Tcf7l1 mRNA, have been suggested to arise following reprogramming to an earlier embryonic stage (Mizuno et al., 2010), and thus it is important to understand how Wnt/β-catenin and Tcf7l1 function. Previous direct experiments showed that ectopic Tcf7l1 expression and Wnt3a both stimulate xenograft tumor formation, mammosphere formation, and colony formation in Matrigel from breast cancer cell lines (Slyper et al., 2012). Although it is formally possible that Tcf7l1-β-catenin complexes may act as transactivators for a set of target genes critical for breast cancer cells, the data presented here do not support this possibility. Tcf7l1 displayed only repressor activity in reporter assay experiments, and Tcf7l1 was degraded following CHIR treatments. We propose two non-mutually-exclusive possibilities: (1) Tcf7l1 and Wnt/β-catenin signals mediate parallel effects, each stimulating tumor cells, and (2) Tcf7l1-β-catenin complexes have a biochemical activity that is distinct from the classical transactivator activity. The former possibility is supported by the recent demonstration of a Wnt/Gsk3/Slug/Snail signaling axis affecting triple-negative breast cancers (Wu et al., 2012b).

The effects of β-catenin on Tcf7l1 are most parsimoniously explained by a mechanism of β-catenin directly inhibiting Tcf7l1 binding to chromatin. Experiments examining the effects of β-catenin on the Tcf/Lef interaction with naked DNA showed little or no effect on binding in vitro, whereas β-catenin interaction significantly affected binding to chromatin by Lef1 (Tutter et al., 2001). Interestingly, mutational analysis of Lef1 indicated that an amino terminal region provides intramolecular inhibition of chromatin binding. β-catenin binding blocks the intramolecular inhibition, thereby stimulating Lef1 binding to chromatin (Tutter et al., 2001). Although the effect of β-catenin on Lef1 is different from that predicted for Tcf7l1, these previous findings demonstrate both positive and negative regulation of chromatin binding via the β-catenin interaction region of Tcf/Lef proteins. Further research is necessary to elucidate the biophysical and biochemical nature of β-catenin’s effects on the chromatinbinding properties of Tcf7l1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

IHC Staining and Scoring of Mammary Tumor Microarray

Quantitative analysis (i.e., scoring)of IHC was performed without knowledge of specimen identification. Scoring was based on a combination of the intensity of stained cells and the percentage of tissue. Separate values for nuclear and cytoplasmic Tcf7l1 immunoreactivity were determined for each sample. Total Tcf7l1 IHC scores were calculated using a modified Reiner scoring system (Reiner et al., 1990) by multiplying the intensity of staining (0–3 value) by the percentage of positive cells. Ranking and scores for β-catenin levels and localization were previously described in Khramtsov et al. (2010).

Statistical Analyses of Tumor RNA and Protein Expression Data

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the overall effects of stage on nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total Tcf7l1. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction was used to conduct pairwise comparisons among four stages. A two-sample t test was used to compare Tcf7l1 mRNA between basal and nonbasal groups. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare Tc7l1 nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total IHC scores between basal and nonbasal groups and between luminal A and nonluminal A groups. Spearman correlations determined the relationships between nuclear Tcf7l1 and cytoplasmic β-catenin; p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jackson Hoffman, Yuka Shimizu, and Alan Tseng for helpful discussions and work associated with the manuscript, Weihua Gao at the UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) for assistance with biostatistical services, Liza Benevolenskaya for assistance with tumor microarray studies, Sergei Sokol for providing the Tcf3-P2/3/4 mutant DNA, and Rudolf Grosschedl for providing the β-cateninΔC plasmid DNA. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1-CA128571 to B.J.M. and UL1TR000050 to the UIC CCTS) and the American Cancer Society Illinois Division (215889 to K.H.G.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures and four figures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.001.

REFERENCES

- Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CM, Goel S, Fakhraldeen SA, Kim S. Wnt signaling in mammary glands: plastic cell fates and combinatorial signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, Moon RT, Kimelman D. A beta-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2359–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Waterman ML. TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo RA, Cox RT, Moline MM, Roose J, Polevoy GA, Clevers H, Peifer M, Bejsovec A. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature. 1998;395:604–608. doi: 10.1038/26982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels DL, Weis WI. Beta-catenin directly displaces Groucho/ TLE repressors from Tcf/Lef in Wnt-mediated transcription activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:364–371. doi: 10.1038/nsmb912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filali M, Cheng N, Abbott D, Leontiev V, Engelhardt JF. Wnt-3A/beta-catenin signaling induces transcription from the LEF-1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33398–33410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer FC, Lacroix-Triki M, Savage K, Arnedos M, Lambros MB, MacKay A, Natrajan R, Reis-Filho JS. β-Catenin pathway activation in breast cancer is associated with triple-negative phenotype but not with CTNNB1 mutation. Mod. Pathol. 2011;24:209–231. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart M, Concordet JP, Lassot I, Albert I, del los Santos R, Durand H, Perret C, Rubinfeld B, Margottin F, Benarous R, Polakis P. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikasa H, Sokol SY. Phosphorylation of TCF proteins by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:12093–12100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikasa H, Ezan J, Itoh K, Li X, Klymkowsky MW, Sokol SY. Regulation of TCF3 by Wnt-dependent phosphorylation during vertebrate axis specification. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JA, Wu CI, Merrill BJ. Tcf7l1 prepares epiblast cells in the gastrulating mouse embryo for lineage specification. Development. 2013;140:1665–1675. doi: 10.1242/dev.087387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovanes K, Li TW, Waterman ML. The human LEF-1 gene contains a promoter preferentially active in lymphocytes and encodes multiple isoforms derived from alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1994–2003. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Nagai S, Nishita M, Meneghini M, Barker N, Waterman M, Bowerman B, Clevers H, Shibuya H, et al. The TAK1-NLK-MAPK-related pathway antagonizes signalling between betacatenin and transcription factor TCF. Nature. 1999;399:798–802. doi: 10.1038/21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K. Regulation of lymphoid enhancer factor 1/T-cell factor by mitogen-activated protein kinase-related Nemo-like kinase-dependent phosphorylation in Wnt/betacatenin signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:1379–1389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1379-1389.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova NB, Dimos JT, Schaniel C, Hackney JA, Moore KA, Lemischka IR. A stem cell molecular signature. Science. 2002;298:601–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KF, Ng DY, Jayakumaran G, Wood GA, Koide H, Doble BW. β-catenin enhances Oct-4 activity and reinforces pluripotency through a TCF-independent mechanism. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khramtsov AI, Khramtsova GF, Tretiakova M, Huo D, Olopade OI, Goss KH. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation is enriched in basallike breast cancers and predicts poor outcome. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;176:2911–2920. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li VS, Ng SS, Boersema PJ, Low TY, Karthaus WR, Gerlach JP, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Maurice MM, Mahmoudi T, et al. Wnt signaling through inhibition of beta-catenin degradation in an intact Axin1 complex. Cell. 2012;149:1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lόpez-Knowles E, Zardawi SJ, McNeil CM, Millar EK, Crea P, Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL, O’Toole SA. Cytoplasmic localization of beta-catenin is a marker of poor outcome in breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:301–309. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyashenko N, Winter M, Migliorini D, Biechele T, Moon RT, Hart-mann C. Differential requirement for the dual functions of β-catenin in embryonic stem cell self-renewal and germ layer formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:753–761. doi: 10.1038/ncb2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill BJ, Gat U, DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Tcf3 and Lef1 regulate lineage differentiation of multipotent stem cells in skin. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1688–1705. doi: 10.1101/gad.891401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill BJ, Pasolli HA, Polak L, Rendl M, Garcίa-Garcίa MJ, Anderson KV, Fuchs E. Tcf3: a transcriptional regulator of axis induction in the early embryo. Development. 2004;131:263–274. doi: 10.1242/dev.00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H, Spike BT, Wahl GM, Levine AJ. Inactivation of p53 in breast cancers correlates with stem cell transcriptional signatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:22745–22750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destrée O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R. Wnt signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, van Ooyen A, Cox D, Fung YK, Varmus H. Mode of proviral activation of a putative mammary oncogene (int-1) on mouse chromosome 15. Nature. 1984;307:131–136. doi: 10.1038/307131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Neumeister B, Spona J, Reiner G, Schemper M, Jakesz R. Immunocytochemical localization of estrogen and progesterone receptor and prognosis in human primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7057–7061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose J, Molenaar M, Peterson J, Hurenkamp J, Brantjes H, Moerer P, van de Wetering M, Destre´e O, Clevers H. The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf-3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature. 1998;395:608–612. doi: 10.1038/26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose J, Huls G, van Beest M, Moerer P, van der Horn K, Goldschmeding R, Logtenberg T, Clevers H. Synergy between tumor suppressor APC and the beta-catenin-Tcf4 target Tcf1. Science. 1999;285:1923–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomonis N, Schlieve CR, Pereira L, Wahlquist C, Colas A, Zambon AC, Vranizan K, Spindler MJ, Pico AR, Cline MS, et al. Alternative splicing regulates mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10514–10519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912260107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slyper M, Shahar A, Bar-Ziv A, Granit RZ, Hamburger T, Maly B, Peretz T, Ben-Porath I. Control of breast cancer growth and initiation by the stem cell-associated transcription factor TCF3. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5613–5624. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike BT, Engle DD, Lin JC, Cheung SK, La J, Wahl GM. A mammary stem cell population identified and characterized in late embryogenesis reveals similarities to human breast cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal FJ, Burgering BM, van de Wetering M, Clevers HC. Tcf-1-mediated transcription in T lymphocytes: differential role for glycogen synthase kinase-3 in fibroblasts and T cells. Int. Immunol. 1999;11:317–323. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamos JL, Weis WI. The β-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a007898. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Rendl M, Fuchs E. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 2004;303:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutter AV, Fryer CJ, Jones KA. Chromatin-specific regulation of LEF-1-beta-catenin transcription activation and inhibition in vitro. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3342–3354. doi: 10.1101/gad.946501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, et al. Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman ML. Lymphoid enhancer factor/T cell factor expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:41–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1025858928620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J, Kalkan T, Gomez-Lopez S, Eckardt D, Cook A, Kemler R, Smith A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 alleviates Tcf3 repression of the pluripotency network and increases embryonic stem cell resistance to differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:838–845. doi: 10.1038/ncb2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CI, Hoffman JA, Shy BR, Ford EM, Fuchs E, Nguyen H, Merrill BJ. Function of Wnt/β-catenin in counteracting Tcf3 repression through the Tcf3-β-catenin interaction. Development. 2012a;139:2118–2129. doi: 10.1242/dev.076067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZQ, Li XY, Hu CY, Ford M, Kleer CG, Weiss SJ. Canonical Wnt signaling regulates Slug activity and links epithelial-mesenchymal transition with epigenetic Breast Cancer 1, Early Onset (BRCA1) repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012b;109:16654–16659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205822109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost C, Torres M, Miller JR, Huang E, Kimelman D, Moon RT. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1443–1454. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.