Abstract

Purpose

“Physicians-recruiting-physicians” is the preferred recruitment approach for practice-based research. However, yields are variable; and the approach can be costly and lead to biased, unrepresentative samples. We sought to explore the potential efficiency of alternative methods.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the yield and cost of 10 recruitment strategies used to recruit primary care practices to a randomized trial to improve cardiovascular disease risk factor management. We measured response and recruitment yields and the resources used to estimate the value of each strategy. Providers at recruited practices were surveyed about motivation for participation.

Results

Response to 6 opt-in marketing strategies was 0.40% (53/13290), ranging from 0% to 2.86% by strategy; 33.96% (18/53) of responders were recruited to the study. Of those recruited from opt-out strategies, 8.68% joined the study, ranging from 5.35% to 41.67% per strategy. A strategy that combined both opt-in and opt-out approaches resulted in a 51.14% (90/176) response and a 10.80% (19/90) recruitment rate. Cost of recruitment was $613 per recruited practice. Recruitment approaches based on in-person meetings (41.67%), previous relationships (33.33%), and borrowing an Area Health Education Center’s established networks (10.80%), yielded the most recruited practices per effort and were most cost efficient. Individual providers who chose to participate were motivated by interest in improving their clinical practice (80.5%); contributing to CVD primary prevention (54.4%); and invigorating their practice with new ideas (42.1%).

Conclusions

This analysis provides suggestions for future recruitment efforts and research. Translational studies with limited funds could consider multi-modal recruitment approaches including in-person presentations to practice groups and exploitation of previous relationships, which require the providers to opt-out, and interactive opt-in approaches which rely on borrowed networks. These approaches can be supplemented with non-relationship-based opt-out strategies such as cold calls strategically targeted to underrepresented provider groups.

INTRODUCTION

Randomized trials in which the primary care practice is the unit of randomization are important tools with which to determine the best ways to improve the quality of medical care [1] and to accelerate the translation of research into practice. However, the methodological underpinnings of translational research of this type are only recently garnering attention and little work has been done to understand how to design these resource-intensive studies in the most cost-effective and efficient way. While recruitment of healthcare practices to such research has been studied, relatively little is known about which strategies for recruiting primary care practices for such studies are both effective and economical [2–10].

Research to date has focused on recruiting individual providers either to single studies or to practice-based research networks [11] using either convenience samples or via random selection through larger sampling frames [5, 7]. The methodological limitations of convenience and volunteer samples of practices have been acknowledged [2, 7, 12–14] and strategies to assess representativeness and to reduce bias have been employed [7]. Yet, the time frames and funding limitations of most translational research pose challenges for achieving these standards. Still other research has sought to identify the most effective strategies. Accordingly, recruitment strategies have been studied in a number of ways to describe the most effective methods. For example, the degree of personal relationship of the recruiter and recruit have been compared, as well as the method of communication (phone or in person) [15–16]. Personal contact with providers and exploitation of existing relationships, have been reported to be effective [2]. The “physicians-recruiting-physicians” method, in which local physician leaders are utilized to recruit practices, is highly regarded, producing response rates ranging from 39–91% [2–7]. The strategies which appear to be successful also seem to be subject to the greatest potential for bias, and moreover, could potentially be the most resource intensive [8]. Physician time is expensive; and even a personal contact strategy utilizing less expensive personnel would be potentially more costly than a mail-based approach.

Incentives are thought to be important in provider recruitment, but little research confirms assumptions regarding why healthcare providers might be motivated to participate in research. Resource limitations further constrain the types of incentives which can be offered and continuing education credits are sometimes assumed to be an acceptable incentive to motivate providers to participate in research, in contrast to cash payments and other economic incentives such as reductions in malpractice premiums for participation [5].

In a retrospective analysis of 10 passive and active recruitment strategies used in a campaign to recruit a diverse sample of primary care providers to a randomized trial of cardiovascular disease management tools, we assessed the relative success and cost of each strategy and elicited participating providers’ reasons for joining the study. We hypothesized that recruitment through an existing educational network of healthcare providers would be efficient and produce a diverse sample of practices and that the technological tools used in the study, coupled with continuing education credit opportunities would be sufficient incentive for providers to participate.

METHODS

In an effort to minimize physician burden during recruitment, reduce costs, and maximize representation of minority providers, we utilized the established relationships of the local Northwest Area Health Education Center (AHEC) network of primary care practices to recruit primary care providers, but ultimately augmented this strategy with additional approaches to reach recruitment targets. After recruiting 68 primary care practices in central North Carolina, we conducted a retrospective analysis of the relative effectiveness and costs of practice recruitment strategies to determine the value of each strategy. In addition, we surveyed recruited providers about their reasons for participating in the study and explored differences in their responses by gender, race/ethnicity, and years since residency.

Setting

Guideline Adherence for Heart Health (GLAD Heart) is a practice-based, randomized controlled trial designed to test technology-based interventions on adherence to two cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines: the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel (ATP3) [17] and the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) [18]. Providers in practices randomized to the ATP3 arm received a personal digital assistant with an ATP3 guideline-based cholesterol management software program. Practices in the JNC7 arm received automated blood pressure devices. All practices received performance feedback, continuing medical education opportunities, and semi-annual group academic detailing sessions. The Wake Forest University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Practice Recruitment

Recruitment strategies were targeted at both individual providers and healthcare practices, either through a practice manager or through a practice network, and were offered in both opt-in and opt-out format. In this paper, a response refers to the initial step required by an individual healthcare provider in an opt-in recruitment strategy: responding to study recruitment material by contacting the GLAD Heart study office to express interest or gain more information. This initial contact does not necessarily mean the provider’s practice has been recruited. Only when the provider takes the action to respond and actually qualifies for and joins the study, is this considered a recruit. Because some of the practice-based recruitment strategies utilized in GLAD HEART consisted of study staff initiated contacts (thus requiring the practice to opt-out), describing response for these attempts is not appropriate. Recruitment is defined as having occurred when an eligible practice returned the letter of agreement to enroll in the study, regardless of whether the practice or its providers opted in or opted out.

Providers and practices may have received multiple opportunities to participate. Participation opportunities were not offered in a predetermined sequential order. In addition, more than one provider from a single practice may have responded to recruitment materials. Responding providers may or may not have met eligibility criteria; and, responding providers may or may not have decided to participate.

Recruitment Material

The main recruitment material was a professionally designed, one-page color flyer describing the research study, participation benefits and practice responsibilities. Multiple contact mechanisms, including a toll-free telephone number, fax number, mailing address, and e-mail address were provided. Depending on the recruitment strategy used, the flyer was accompanied by a cover letter, cover fax, or stood alone. Cover letters for the AHEC survey were on AHEC letterhead, signed by the director of AHEC. Cover letters for the minority provider direct mail were on the study institution’s letterhead and signed by the physician principal investigator. For the mass fax effort, the cover fax listed physician investigators and was signed by the physician principal investigator. For cold calls, follow-up fax cover sheets were personalized by the research staff member communicating with the practice.

Recruitment Strategies

Ten different recruitment strategies were used in GLAD Heart, six opt-in strategies and three opt-out strategies, and one strategy which combined opt-in and opt-out methods. The opt-in strategies were targeted to individual healthcare providers in a wide catchment area. We used three mass dissemination approaches. Strategy 1 consisted of mass advertising. Advertisements were placed in three county and one regional medical society newsletter. These advertisements briefly described the study and invited interested providers to call for additional information. In addition to the newsletters, study staff wrote and submitted an editorial to a regional magazine for physicians describing the current state of guideline compliance and describing the study as one experimental method of improving compliance. Strategy 2 consisted of mass distribution. We distributed recruitment materials at three healthcare provider events: a Family Medicine CME conference, a state-wide quality of care conference, and a regional PA association meeting. Materials briefly described the study and invited interested providers to call for additional information. Strategy 3: We purchased fax numbers for 3,881 primary care providers holding American Medical Association memberships in a 150-mile radius of Winston-Salem (including physicians in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia). Physicians on this list were faxed a personally addressed cover page and recruitment flier, inviting participation in the study.

Strategy 4: To boost participation by minority providers, we acquired a mailing list from a state-wide organization of minority physicians, and mailed non-personalized letters and recruitment materials to members. Strategy 5: Another opt-in strategy used was the opinion leader e-mail. This strategy used the influence of potential opinion leaders at physician and insurance organizations to recruit practices. We asked quality improvement colleagues at the state Primary Care Association and a health insurance company to send recruitment materials by email with their personal endorsement of the study. Strategy 6: We also made in-person presentations to provider professional meetings. The principal investigator attended a regional Physician Assistant organization meeting and made a presentation regarding the study.

Three strategies targeted primary care practices (not captured by the AHEC survey, below) directly and required them to opt-out of participation. Strategy 7: Cold calls were made to practices not captured by providers from the AHEC survey to determine interest in the project. Primary care practices within a 2-hour radius of Winston-Salem were identified using local telephone books of surrounding communities, a medical society’s membership list, and health maintenance organization provider directories. Calls were made to practice managers and information was sent for distribution to the health care providers in the practice. Follow-up calls were repeated until the practice made a decision regarding participation. Strategy 8: Presentations about the study were made to physician practice groups in three local communities after obtaining permission from medical directors. Strategy 9: Study investigators contacted practices which had previously enrolled in their other practice-based research studies, thereby, exploiting professional relationships.

The primary strategy, which combined an opt-in and opt-out approach, was the use of an interest survey obtained from primary care physicians participating in NW AHEC activities (Strategy 10). This strategy drew upon the existing infrastructure of the NW AHEC. AHEC consortiums serve as a partnership between the university health science centers in state and local communities and are designed to provide health professionals with education and training opportunities. In addition to providing continuing education opportunities, electronic medical information and library services to healthcare providers in its network, NW AHEC places medical, physician assistant, nursing, and other allied health students with practicing providers who agree to serve as preceptors. Of the 670 community-based physicians in the NW AHEC database at the start of the study, more than 394 providers in 207 different practices served as preceptors, and thus had an established relationship with NW AHEC. We incorporated 11 brief survey items into the NW AHEC’s annual survey of primary care providers in the region. Data collected from this survey gauged providers’ interest in participating in a study using hand held computer technology and their practices’ information technology infrastructure. We contacted the practice manager of each physician in our catchment area who indicated interest to share information regarding the GLAD Heart study with the providers in that practice.

Measurements

The marketing strategy to which a provider was responding was documented. Records of circulation rates for periodicals and e-mail, as well as membership numbers for each organization to which we mailed recruitment materials were maintained. For cold calls, records of the number of practices with which we were able to communicate our recruitment message were documented.

To estimate costs, the following were recorded: the proportion of study staff and faculty time devoted to each strategy, including travel time for strategies requiring in-person meetings; communication costs (postage, long distance, and fax charges) proportionate to staff effort; materials development time and printing costs for each strategy; and list purchase and advertising expenses. Total costs per strategy were divided by the number of practices for which the strategy was the primary recruitment approach. Where two strategies were combined, costs of the secondary strategy are not included. To test whether strategies based on prior relationships produced significantly greater results, the Chi-squared test was used to assess differences in the proportions of recruited practices in two categories.

Finally, in a survey of healthcare providers in practices which ultimately enrolled in the study, providers indicated reasons for participating in the study from a list of 10 possible reasons. Provider characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, specialty and years since residence were also collected.

Analysis

We conducted a retrospective, secondary analysis of monitoring and cost data to assess the maximum possible effectiveness of each strategy and to provide a conservative estimate of the costs of each strategy. Descriptive statistics and graphing techniques were used to estimate the relative value of the recruitment strategies. Chi-square tests were used to assess the association between survey responses and provider characteristics. In the case of sparse data, Fisher’s exact tests were used instead.

RESULTS

Ultimately we recruited 68 practices. The majority of practices were Family Medicine (74%) The mean number of providers per practice was 4, ranging from 1 to 14. Nineteen percent of the practices had a solo provider. For 15% of the recruited practices, the majority of the providers in the practice were minorities. In 34% of the practices the majority of the providers were female. Table 1 summarizes practice characteristics.

Table 1.

Practice Characteristics for Recruited Practices

| Practice Characteristics | N=68 |

|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 17 (25%) |

| Family Medicine | 50 (74%) |

| Predominantly Minority Practice | 10 (15%) |

| Predominantly Female Practice | 23 (34%) |

| Physician providers (mean and range) | 3 (1,9) |

| Total Providers (mean and range) | 4 (1,14) |

| Solo provider practice | 13 (19%) |

Opt-In Response

Response to the six opt-in marketing tactics (Strategies 1 through 6 above) was 0.40% (53 responses from 13,290 placements), but response to the opt-in portion of the combined strategy (Strategy 10 above) was 51% (90 responses from 176 surveys sent to adult primary care providers). Approximately one-third of responders to the marketing strategies (strategies 1–6) were recruited to the study [34% (18/53)], while 21% (19/90) of survey responders (Strategy 10) were recruited to the study. The mass fax effort (Strategy 3)yielded a high absolute response (44 calls), compared to other strategies. The least successful strategy in terms of response was the editorial published in a local medical magazine (Strategy 1). Although the target readership was 3,500, no physicians responded to the article. Table 2 shows the response rates for each strategy for which this could be calculated.

Table 2.

Response Rates and Recruitment Rates by Recruitment Strategy

| Strategy | N | Response | Recruits |

Cost per Recruit |

Extra Cost |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opt-In Strategies | ||||||

| 1 | Mass Advertising | $3,958 | ||||

| Medical Society Inserts | 5350 | 2 (0.04%) | 1 (0.02%) | |||

| Published Article | 3500 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 2 | Conference | 106 | 1 (0.94%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Distribution | $627 | |||||

| 3 | Mass Fax | 3882 | 44 (1.13%) | 13 (0.33%) | $1,138 | |

| 4 | Minority Provider | 319 | 4 (1.25%) | 3 (0.94%) | ||

| Direct Mail | $401 | |||||

| 5 | Opinion Leader | 98 | 1 (1.02%) | 1 (1.02%) | ||

| $101 | ||||||

| 6 | In-Person Provider | 35 | 1 (2.86%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Presentation | $323 | |||||

| Response | 13290 | 53 (0.40%) | 18 (0.14%)** | $1,167 | ||

| Opt-Out Strategies | ||||||

| 7 | Cold Calls | 318 | --* | 17 (5.35%) | $331 | |

| 8 | In-Person Practice | 12 | --* | 5 (41.67%) | ||

| Presentation | $217 | |||||

| 9 | Previous | 27 | --* | 9 (33.33%) | ||

| Relationship | $383 | |||||

| Recruitment | 357 | 31 (8.68%) | $328 | |||

| Combination Opt-In and Opt-Out | ||||||

| 10 | AHEC Survey | 176 | 90 (51.14%) | 19 (10.80%) | $553 | |

| Total Recruitment | 13823 | 68 (0.49%) | $613¥ | |||

Providers/practices were contacted directly by study staff. Response rate cannot be calculated.

Proportion of recruits from total responses

Average cost per recruit, including expenditures for strategies which resulted in no recruit

Recruitment

For the outcome of interest, the actual recruitment of practices, the average rate was 0.49% (68 practices recruited from 13,823 placements), ranging from 0 to 42%. The practice-based approaches based on in-person meetings (Strategy 8) (42%) and previous relationships (Strategy 9) (33%) yielded the most recruited practices per attempt, followed by the AHEC strategy (Strategy 10) (11%), and the cold calls (Strategy 7) (5%). The mass advertising (published article and medical society inserts), opinion leader email, and medical conference distribution (Strategies 1, 2 and 5) were the least effective strategies in producing recruited practices. Minority provider direct mail (Strategy 4) resulted in only a 1% recruitment rate, but produced three practices.

Overall recruitment expenses were estimated at $41,340, for an average of $613 per recruited practice. The cost per recruit by strategy is listed in Table 2. Less expensive approaches included opinion leader e-mail, in-person group practice presentations, cold calls, and exploitation of previous relationships. Direct fax was one of the more costly strategies.

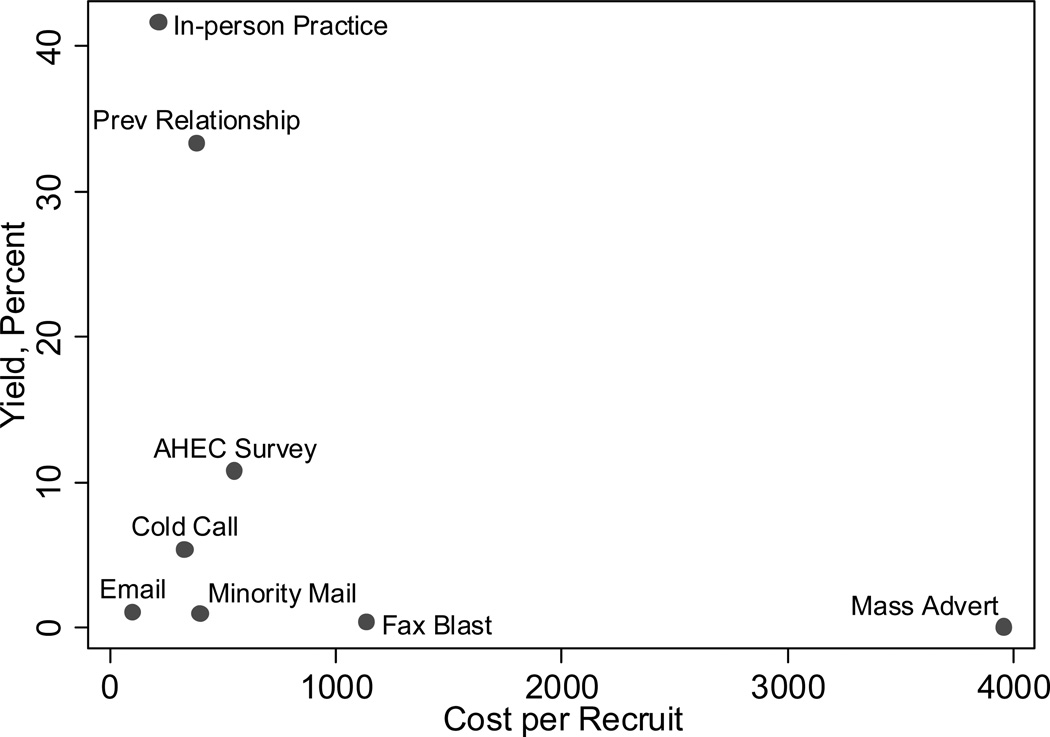

Costs per Practice

For each of the successful strategies, we graphed the recruitment yield by cost per recruited practice in a scatter plot (Figure 1) to identify the most cost efficient recruitment strategies, that is, those which maximized recruitment yield with the least costs. The three most efficient strategies were 1) in-person presentations; 2) contacting previous relationships; and 3) surveying AHEC providers.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of Cost Per Recruit by Percent Recruitment Yield

Reasons for Participation

Finally, for those healthcare providers who ultimately joined the study, 84% completed the baseline survey. Table 3 shows the frequency of each reason cited for participation. “Interest in improving clinical practice,” “interest in contributing to primary prevention for CVD,” and desire to “invigorate practice with new ideas” were the most frequently cited reasons for wanting to participate in the study. A marginal gender difference was found in the third ranked response “invigorate my practice with new ideas” (p-value = 0.04) with male providers more likely than female providers to select this as a motivation to participate in the study. There were no other differences in the top ranked responses by provider race/ethnicity, gender, medical specialty (internal medicine vs. family medicine), or years since residency completed (data not shown).

Table 3.

Reasons for participating in GLAD Heart

| Participation Reason* | N 184 |

Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Interested in improving my clinical practice | 157 | 81% |

|

Interested in contributing to primary prevention for Coronary Vascular Disease |

106 | 54% |

| Invigorate my practice with new ideas | 82 | 42% |

| Like to remain involved in research initiatives | 61 | 31% |

| Ability to earn convenient CME credit | 37 | 19% |

|

Affiliation with Wake Forest University School of Medicine is good for my practice |

32 | 16% |

| Wanted to receive hand held computer (personal digital assistant—PDA) | 30 | 15% |

| Desire to help my colleagues | 27 | 14% |

| Wanted to receive automated blood pressure device | 18 | 9% |

| Other | 14 | 7% |

Providers could select more than one reason for participation

DISCUSSION

Although we hypothesized that opt-in recruitment strategies would be a more efficient use of study resources, requiring less staff time and effort, we found that the greatest yield was in those strategies that required the practice to opt-out. These strategies appear to be resource intensive, and often require the practice manager to act as a intermediary on behalf of the study. However, by putting the onus on healthcare providers to actively respond to recruitment materials through the opt-in strategies, we had to target a greater number of providers and spend more for materials and delivery, which made these strategies less efficient, confirming the findings of McBride et al [8]. The opt-out strategies did require detailed record keeping, vigilance and reminder systems to adequately follow-up with practices until their final decision was made. Still, our research suggests that this more intensive effort applied to a smaller pool of providers may be more efficient.

Contrary to other findings [2], a high degree of personal relationship was not always necessary for success. We did confirm that those strategies that relied on established relationships were successful approaches; however, other strategies that did not utilize pre-existing relationships such as in-person presentations to groups, cold calls, and mass fax were relatively effective and potentially affordable, deserving additional evaluation.

Cold calls were suprisingly robust in their absolute contribution to our sample and deserve further, cautious investigation. Published literature suggests that attempts to recruit practices with no previous relationship is least effective [2], but this strategy accounted for 25% (n=17) of our total recruited sample. Elsewhere, recruitment gains have been reported as the degree of personal relationship between the recruiter and recruit intensified, ranging from 26% when the recruiter did not know the recruit to 59% when the recruiter did know the recruit [19]. Another study showed participation rates of 77% when the recruiter was an acquaintance, 79% when there was no relationship, and 95% when the recruiter was a friend [15]. It should be noted that the cost efficiency of this strategy may be due to the relatively modest level of resources which were invested in this approach. Further, we were able to broadcast more cold calls than other more targeted strategies because we invested so little in the development of relationships. The main benefit of the cold call strategy is that it did not require expensive physician time. From our experience, we would recommend evaluating this approach when used strategically after exhausting more effective strategies, and applied only to targeted geographic areas or provider group types in which recruitment yields need to be increased.

Conduct of in-person presentations to practice groups, even though there were no prior established relationships, was the least costly per recruitment yield. Other research has shown that significant gains in recruitment were seen from a face-to-face contact compared to letter [4] and telephone contact [2]. Perhaps the in-person contact and the multiple contacts necessary to garner approval to conduct the in-person presentation serve as a form of relationship building on which the other cost effective strategies rely.

While the mass fax effort was costly and did not have a high ratio of recruits to recipients, it did provide 19% (n=13) of our recruited sample. Fax costs could have been reduced and yield improved, had we better targeted our initial provider selection to geographic areas that were closer by travel distance instead of using an absolute 150-mile radius of our institution. Several interested practices were deemed ineligible because travel distance to their practice was too far. Because of the absolute large response and the absolute numbers of recruits it generated, it is worth refining and repeating this strategy to study its effectiveness and efficiency.

Mass advertising methods do not seem to be useful efforts for practice-based recruitment. However, marketing theory suggests that multiple messages increase receptivity to the message, and it is unknown whether the advertisements were seen by eventual recruits and whether their presence primed the recruits’ receptivity to the strategy to which they eventually responded. Only one provider responding to our efforts mentioned seeing any of our placements. Even if mass advertising were a boost to other efforts, it was a costly adjunct. Before using this strategy in subsequent recruitment efforts, more research would be necessary to understand the proportion of medical society members who actually read their organization’s publication and respond to the advertising within it. The same market research would be needed for regional physician publications.

As demonstrated in other studies, strategies which exploited previous relationships were quite effective, and we learned, cost efficient. Relying on investigators’ previous relationships is relatively low cost and provides a high yield of recruited practices. However, borrowed relationships, such as that of an AHEC network is an acceptable strategy to further recruitment efforts. This strategy provided a moderate yield at a moderate cost and has the added benefit of extending the recruitment network beyond investigators’ personal networks, and, potentially, providing a more diverse sample of practice participants. Networks such as the AHEC network may be a cost-efficient alternative to practice-based research networks. Costs for developing and maintaining research networks are not typically reported, so it is unknown if the infrastructure investment leads to efficiencies in recruitment costs. Piggybacking research efforts onto educational network efforts could potentially spread infrastructure investment across more funding resources. Even as an opt-in strategy, the AHEC survey was more successful than the other opt-in approaches. Perhaps AHEC providers are more likely to volunteer than other providers—they have already volunteered to serve as preceptors.

Finally, providers who voluntarily participated in our study reported being motivated by the same reasons, regardless of individual provider characteristics. Other studies [2,3,5] have shown that those who choose to participate in practice-based research are more likely to be non-Hispanic white, male, younger, and be from rural areas than those who decline to participate. We did not collect information on those who refused, but our results do show that for those ultimately participating, interest in improving quality and preventing CVD was key, regardless of race/ethnicity, gender, and years since residency. Consistent with other studies on practice recruitment [2], incentives, continuing education credit, and affiliation with the academic institution were motivating factors for relatively few. Altruism did not seem to be a significant reason for participation, contrary to research on patient participation [20–27]. Other research is needed to better understand how to motivate providers who are not open to self-improvement, especially since the generalizability of trial findings would be limited due to selection bias.

The main strength of this study is that we provide precise quantification of contacts and estimation of direct costs, which is not generally reported. These estimations offer a good basis for researchers planning similar studies, although not all strategies described can be applied in all health care settings and their actual costs may differ.

Limitations

Our main limitation is that we did not randomize providers or practices to recruitment strategies. The time constraints of initiating the main study did not allow for controlled rollout of these strategies, limiting us to retrospective anlaysis of the data collected. In addition, due to the lack of information regarding which providers were employed by each practice at the time cold calls were placed and to the restrictions on contact information placed by list vendors, we did not have enough information for full post hoc assessment of the amount of overlap of the various strategies. It is quite likely that healthcare providers may have received more than one recruitment offer. In addition, costs calculated are direct costs. We do not have data to obtain indirect costs. For the establishment of the AHEC network and those relationships built in previous studies, these costs could be substantial. Therefore, our analysis offers an optimistic estimate of the effects and costs of each of these strategies. While we cannot infer that the yields and resource expenditures for the top strategies can be replicated with similar magnitude, we can surmise that the strategies shown to be ineffective and to be of low value, truly are.

The generalizability of these results are further limited to practice communities with an existing AHEC network with similar resources; investigators with previous relationships with other practices; and other professional organizations we drew upon. It should be noted that the NW AHEC program is provided $5.2 million annually from the North Carolina General Assembly as part of one of the oldest higher education systems in the country. Thus these results are most generalizable to other NC AHEC programs as they have identical funding. Although the total amount of funding for AHEC programs in NC is among the highest per capita across the 44 states with AHEC programs, many of the other state AHECs have similar community preceptor relationships for training medical students in community settings. In addition, similar profesional organizations and networks of practices exist where AHEC networks do not exist, as most health professional schools have established networks of practices which assist in the training of their students.

In addition, we did not assess sytematically why some providers who responded did not ultimately participate in the study. While a portion of these did not meet study eligibility criteria, others responded with the ambiguous reason “not enough time,” and some could not convince other providers in their practice to participate. A better understanding of the motivational differences between intial responders and recruited responders could be used to craft effective strategies to transform these initial respondents into study participants.

Conclusions

Recruiting healthcare practices to research studies is an arduous process and little is known about how best to apply limited resources. Our study supports the use of physician networks and face-to-face strategies, as has been previously reported, but also suggests the need for further research on other opt-out strategies such as cold calling and supplemental approaches to target ethnically and geographically diverse participants. With all of these strategies, careful collection and analysis of response, recruitment and cost data, especially in the later phases of recruitment, should occur to provide additional guidance regarding which kinds of research recruitment strategies for practice-based trials are most productive and cost efficient. Relatively few research dollars currently are devoted to translational research, so practice based research studies must be done economically to build the evidence base for quality of care interventions. Without information on the expense of practice recruitment strategies, identifying the optimal approach to recruiting a sufficiently large, representative sample at the lowest cost is not possible and may further delay the translation of evidence-based care into practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the GLAD Heart Research staff, Virginia Burnette and Vanessa Duren-Winfield, for their recruitment efforts. Results from these efforts have been presented at the AHA 5th Scientific Forum on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research in Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke, May 17–19, 2004; the 5th International Heart Health Conference, July 13–16, 2004; and the North Carolina AHEC Statewide Meeting, October 6–8, 2004. The study was funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute R01 HL70742.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Sources of Support:

The study was funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute R01 HL70742.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors Shellie Ellis, Alain Bertoni, Denise Bonds, Aarthi Balasubramanyam, Caroline Blackwell, Haiying Chen, C. Randall Clinch, and David Goff, Jr. have no conflicts of interest. Michael Lischke oversees the Northwest Area Health Education Center of Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

Reference List

- 1.Nutting PA, Beasley JW, Werner JJ. Practice-based research networks answer primary care questions. JAMA. 1999:686–688. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.8.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asch S, Connor SE, Hamilton EG, Fox SA. Problems in recruiting community-based physicians for health services research. J Gen Intern Med. 2000:591–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park ER, MacDonald Gross NA, Goldstein MG, DePue JD, Hecht JP, Eaton CA, Niaura R, Dube CE. Physician recruitment for a community-based smoking cessation intervention. J Fam. Pract. 2002:70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid CM, Ryan P, Nelson M, Beckinsale P, McMurchie M, Gleave D, DeLoozef F, Wing LM. General practitioner participation in the second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2001:663–667. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shelton BJ, Wofford JL, Gosselink CA, McClatchey MW, Brekke K, Conry C, Wolfe P, Cohen SJ. Recruitment and retention of physicians for primary care research. J Community Health. 2002:79–89. doi: 10.1023/a:1014598332211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker AE, Campbell MK, Grimshaw JM. A recruitment strategy for cluster randomized trials in secondary care settings. J Eval. Clin. Pract. 2000:185–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West JC, Zarin DA, Peterson BD, Pincus HA. Assessing the feasibility of recruiting a randomly selected sample of psychiatrists to participate in a national practice-based research network. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1998:620–623. doi: 10.1007/s001270050102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride PE, Massoth KM, Underbakke G, Solberg LI, Beasley JW, Plane MB. Recruitment of private practices for primary care research: experience in a preventive services clinical trial. J Fam Pract. 1996:389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearl A, Wright S, Gamble G, Doughty R, Sharpe N. Randomised trials in general practice--a New Zealand experience in recruitment. N Z Med J. 2003:U681–U687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wetzel D, Himmel W, Heidenreich R, Hummers-Pradier E, Kochen MM, Rogausch A, Sigle J, Boeckmann H, Kuehnel S, Niebling W, Scheidt-Nave C. Participation in a quality of care study and consequences for generalizability of general practice research. J Fam Pract. 2005:458–464. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green LA, Miller RS, Reed FM, Iverson DC, Barley GE. How representative of typical practice are practice-based research networks? A report from the Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network Inc (ASPN) Arch Fam Med. 1993:939–949. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.9.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amthauer H, Gaglio B, Glasgow RE, Dortch W, King DK. Lessons learned patient recruitment strategies for a type 2 diabetes intervention in a primary care setting [corrected] Diabetes Educ. 2003:673–681. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey TS, Kinsinger L, Keyserling T, Harris R. Research in the community: recruiting and retaining practices. J Community Health. 1996:315–327. doi: 10.1007/BF01702785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heywood A, Mudge P, Ring I, Sanson-Fisher R. Reducing systematic bias in studies of general practitioners: the use of a medical peer in the[recruitment of general practitioners in research. J Fam Pract. 1995:227–231. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgiel AE, Dunn EV, Lamont CT, MacDonald PJ, Evensen MK, Bass MJ, Spasoff RA, Williams JI. Recruiting family physicians as participants in research. Fam. Pract. 1989:168–172. doi: 10.1093/fampra/6.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kottke TE, Solberg LI, Conn S, Maxwell P, Thomasberg M, Brekke ML, Brekke MJ. A comparison of two methods to recruit physicians to deliver smoking cessation interventions. Arch Intern Med. 1990:1477–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr., Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr., Roccella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosecoff J, Chassin MR, Fink A, Flynn MF, McCloskey L, Genovese BJ, Oken C, Solomon DH, Brook RH. Obtaining clinical data on the appropriateness of medical care in community practice. JAMA. 1987:2538–2542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabbay M, Thomas J. When free condoms and spermicide are not enough: barriers and solutions to participant recruitment to community-based trials. Control Clin. Trials. 2004:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolmie EP, Mungall MM, Louden G, Lindsay GM, Gaw A. Understanding why older people participate in clinical trials: the experience of the Scottish PROSPER participants. Age Ageing. 2004:374–378. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halpern SD, Karlawish JH, Casarett D, Berlin JA, Townsend RR, Asch DA. Hypertensive patients’ willingness to participate in placebo-controlled trials: implications for recruitment efficiency. Am Heart J. 2003:985–992. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanford PD, Monte DA, Briggs FM, Flynn PM, Tanney M, Ellenberg JH, Clingan KL, Rogers AS. Recruitment and retention of adolescent participants in HIV research: findings from the REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) Project. J Adolesc. Health. 2003:192–203. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fry C, Dwyer R. For love or money? An exploratory study of why injecting drug users participate in research. Addiction. 2001:1319–1325. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.969131911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sengupta S, Strauss RP, DeVellis R, Quinn SC, DeVellis B, Ware WB. Factors affecting African-American participation in AIDS research. J Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2000:275–284. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200007010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welton AJ, Vickers MR, Cooper JA, Meade TW, Marteau TM. Is recruitment more difficult with a placebo arm in randomised controlled trials? A quasirandomised, interview based study. BMJ. 1999:1114–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7191.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geller G, Doksum T, Bernhardt BA, Metz SA. Participation in breast cancer susceptibility testing protocols: influence of recruitment source, altruism, and family involvement on women’s decisions. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1999:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]