Abstract

Tyrosine kinases have significant roles in cell growth, apoptosis, development, and disease. To explore the use of zebrafish as a vertebrate model for tyrosine kinase signaling and to better understand their roles, we have identified all of the tyrosine kinases encoded in the zebrafish genome and quantified RNA expression of selected tyrosine kinases during early development. Using profile hidden Markov model analysis, we identified 122 zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes and proposed unambiguous gene names where needed. We found them to be organized into 39 nonreceptor and 83 receptor type, and 30 families consistent with human tyrosine kinase family assignments. We found five human tyrosine kinase genes (epha1, bmx, fgr, srm, and insrr) with no identifiable zebrafish ortholog, and one zebrafish gene (yrk) with no identifiable human ortholog. We also found that receptor tyrosine kinase genes were duplicated more often than nonreceptor tyrosine kinase genes in zebrafish. We profiled expression levels of 30 tyrosine kinases representing all families using direct digital detection at different stages during the first 24 hours of development. The profiling experiments clearly indicate regulated expression of tyrosine kinases in the zebrafish, suggesting their role during early embryonic development. In summary, our study has resulted in the first comprehensive description of the zebrafish tyrosine kinome.

Introduction

Tyrosine kinases

Phosphorylation of the amino acid tyrosine was discovered 33 years ago in mouse cells infected with the polyoma virus.1,2 The viral enzyme v-SRC was shown to phosphorylate tyrosine3,4 and to be essential for Rous sarcoma virus-mediated transformation of cells.5,6 Several other cellular tyrosine kinases were discovered subsequently and were found to act by catalytically transferring the γ-phosphate of ATP to tyrosine residues on proteins. The significance of tyrosine phosphorylation in signaling pathways and physiology has been the subject of several studies, and tyrosine kinases are well-validated targets for cancer therapy.7–9 Tyrosine kinases are also being studied in the context of a growing number of pathological conditions, including neurodegeneration, autoimmunity, inflammation, and infectious diseases. Research during the last 30 years has helped illuminate crucial features of tyrosine kinase protein sequences and structure–function relationships.10–14 Current tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) function by interfering with ATP and/or substrate binding.15,16 Toxicity, nonselectivity, resistance, redundancy, and idiosyncratic clinical response are some issues facing TKI development. There have been few studies on in vivo mechanisms and physiological effects of tyrosine kinase dysregulation, and several tyrosine kinases are yet uninvestigated. The evolution of tyrosine kinase activity and its regulation in metazoans and premetozoans, and its relation to the evolution of multicellularity has been the subject of intriguing recent studies,17, 18 and such research is facilitated by the availability of suitable animal models. Further, studies on tyrosine kinase biology and development of the next generation of small molecule modulators will be significantly strengthened by in vivo studies. In such contexts, the zebrafish has significant potential to be an accessible in vivo model to study tyrosine kinases.

Tyrosine kinases in zebrafish

Developmental roles of some tyrosine kinases in zebrafish have been investigated by studying genetic mutants, gene expression patterns, and the effects of experimentally altering gene expression.

Owing to their significant cellular functions, it is not surprising that past studies show essential roles of both receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinase families in several aspects of embryonic development in zebrafish. They include a wide spectrum beginning from very early events in fertilization and gastrulation to later events in organogenesis and tissue regeneration. The EGFR receptor tyrosine kinase family influences neural crest development, cardiovascular development, and regeneration after injury.19–21 The EPHR family is crucial for gastrulation, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, retinotectal system patterning, and extracellular matrix assembly.22–25 The nonreceptor tyrosine kinase SRC is involved in egg activation during fertilization,26 and FAK has a role in cell adhesion and exhibits noncanonical regulatory phosphorylation.27,28 The MET receptor tyrosine kinase regulates liver and cerebellum development;29–31 the TEC tyrosine kinase is expressed in the zebrafish kidney;32 the TRKB receptor tyrosine kinase is expressed throughout embryonic development and lacks a kinase domain until neurogenesis;33 MuSK functions in neuromuscular synapse formation;34 and PTK7 knockdown results in convergent extension defects.35 The zebrafish cardiovascular system is profoundly influenced by tyrosine kinases. PDGFRβ36 and VEGFR have striking effects on zebrafish angiogenesis37 and analogues of Vadimezan, a multi-kinase inhibitor with effects on VEGFR disrupt angiogenesis in zebrafish.38 The tyrosine kinase TIE1 regulates endothelial cell contact junctions,39 while TIE2 mediates vessel stability and may be the target for statin-induced haemorrhage.40 The cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase JAK2 is encoded by duplicate genes which have distinct expression patterns and functions in hematopoesis,41 and SYK and ZAP70 function redundantly in angioblast migration.42 Development of unique skin features of zebrafish are also influenced by tyrosine kinases. The tyrosine kinases KIT and FMS play essential roles in melanocyte and xanthophore generation in zebrafish stripes,43 and the tyrosine kinase LTK functions in iridophore specification.44 As with TIE and JAK2, duplicate IGF1R tyrosine kinases have overlapping but distinct functional roles in development and physiology,45 highlighting the effects of zebrafish genome duplication events on tyrosine kinase evolution in teleosts. Finally, the use of proteomics has revealed the prevalence and importance of tyrosine phosphorylation pathways in zebrafish and the possibility of studying phosphotyrosine signaling in vivo.46,47

The above studies on zebrafish tyrosine kinases provide insights in the context of a whole organism, and can potentially address important questions regarding physiological roles of tyrosine kinases and tyrosine phosphorylation pathways. While correlating results from the above studies with those in humans, we found that the available literature was not informative with respect to the number of zebrafish tyrosine kinases, their nomenclature, and orthology. We found that sequence databases and other resources were also incomplete in the above respect. An accurate understanding of the developmental and physiological roles of zebrafish tyrosine kinases will ultimately require the comprehensive identification, nomenclature, and orthology analysis of all the tyrosine kinases encoded in the zebrafish genome. Such knowledge will also provide impetus to the use of zebrafish to model human diseases related to tyrosine kinase dysfunction.

Availability of the complete genome sequence of zebrafish allows detailed computational sequence analysis. We created profile hidden Markov models48 of known human and other known tyrosine kinase domain protein sequences, and used the models to search zebrafish protein databases to identify all zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes. We used sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis with human tyrosine kinases to confirm our findings and perform unambiguous orthology assignments. In order to experimentally validate our computational results, we detected the expression of a set of unreported tyrosine kinases representative of all zebrafish tyrosine kinase families during the first 24 h of development using nCounter direct digital detection technology. Our findings and their implications are presented here. The goal of this article is to provide the first comprehensive resource of the zebrafish tyrosine kinome. We anticipate that this information will be useful both for research communities using zebrafish as a developmental and genetic model organism, and for those interested in zebrafish as an in vivo model for tyrosine kinase biology.

Methods

Profile hidden Markov models

The curated RefSeq49 full release collection of zebrafish protein sequences in FASTA format was obtained via ftp from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/refseq/D_rerio/mRNA_Prot/zebrafish.protein.faa.gz. This database is updated regularly and contains all the protein sequences encoded in the zebrafish genome. The latest version of the freely distributable implementation of the profile hidden Markov model (HMM) software HMMER350 was obtained as source code via ftp from the HMMER website ftp://selab.janelia.org/pub/software/hmmer3/3.0/hmmer-3.0-linux-intel-ia32.tar.gz. The HMMER3 source code was compiled on a system equipped with a dual core Intel(R) Pentium(R) 4 3.06 Ghz CPU and 1.0 Ghz RAM, running Ubuntu Linux 9.04 kernel version i686. The documentation and instructions on the website http://hmmer.janelia.org/ were followed for use of the software. A collection of one hundred most diverse tyrosine kinase domain sequences in FASTA format was obtained from the conserved domain database (CDD) of the NCBI.51 The protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) domain family is curated as a conserved domain family cd00192, belonging to the protein kinase superfamily cI09925. The top 148 tyrosine kinase domain sequences (rated according to their similarity to the tyrosine kinase domain consensus) were also obtained similarly. These sequence sets are available on the conserved domain database as multiple sequence alignments in several formats. The tyrosine kinase domain boundary is defined on the basis of three-dimensional structures of the proteins and multiple sequence alignment of the various sequences. The tyrosine kinase domain sequences were aligned and refined using the program MUSCLE52 and reformatted to the ‘Stockholm’ format using the sreformat command of the package Biosquid http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/lucid/man1/sreformat.1.html. Using HMMER3, profile HMMs were built from the multiple sequence alignments of tyrosine kinase domain sequences.

Identification and orthology of zebrafish tyrosine kinases

Tyrosine kinase domain profile HMMs constructed as described above, were used to search the RefSeq zebrafish protein sequence collection. All the protein sequence entries generated by HMMER3 were exported to a spreadsheet and the corresponding cDNA and protein sequences extracted from the ENSEMBL, NCBI, and ZFIN sequence databases. The final protein sequences used in the rest of the study were from ENSEMBL, since this database appeared to have the most complete information. All the entries containing valid tyrosine kinase domain sequences as per the CDD were selected and further verification of their identity and orthology to human tyrosine kinases was done as follows. The gene orthology database of ENSEMBL and the ‘homologene’ database of NCBI provided a starting point for initial assignment. A combination of local and global sequence alignment-based database searches and pairwise alignments were done using the EBI web-based software FASTA, NCBI BLAST, EMBOSS WATER, and EMBOSS NEEDLE. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using CLUSTALW and dendrograms were constructed as described below. Final orthology assignment was based on all the analyses performed.

Multiple sequence alignments and dendrograms

Full-length protein sequences of zebrafish tyrosine kinases identified as described above were subject to multiple sequence alignment, along with available tyrosine kinase domain sequence alignments from the Conserved Domain Database at NCBI. The final alignments were visually examined to identify zebrafish tyrosine kinase domain boundaries. Tyrosine kinase domain sequences of all zebrafish tyrosine kinases were manually extracted from the full-length sequences and assembled into FASTA format files. Pairwise sequence comparison of full-length and tyrosine kinase domain sequences of zebrafish and humans was performed using BLAST to reveal sequence identity. Multiple sequence alignments were performed and dendrograms constructed using full-length tyrosine kinases from zebrafish and humans with the software CLUSTALW. Dendrograms were edited using the program Dendroscope39 for improving appearance of fonts and colors, replotting as circular cladograms, and exporting as images.

Genomic and expression features

Chromosomal number, location, strand orientation, and RNASeq information was inferred from ENSEMBL database entries and manual BLAST/BLAT searches as needed. Wherever applicable, multiple RNASeq IDs corresponding to single ENSEMBL IDs are reported together. Known mutations of zebrafish tyrosine kinases were compiled from the ZFIN database.

Zebrafish maintenance and embryo collection

Embryos from the AB/LF strain were used for RNA extractions, and were maintained between 25.5° and 28.5°C. The staging series described previously53 was used to collect embryos into six different pools (maternal/early cleavage stage, shield stage, 70%–100% epiboly, 3–12 somites, 16–19 hours post-fertilization (h) and 22–26 h; maternal stage embryos were between 2–8 cells).

RNA extraction and NanoString nCounter assay and data analysis

TRI Reagent (Sigma) was used to extract total RNA from frozen embryos at specific developmental stages using the method described by the manufacturer. Gene expression analysis using the nCounter system (NanoString Technologies) was done as described previously.54 The nCounter system uses molecular (fluorescent) barcodes for direct digital detection of individual target mRNA molecules. In brief, sequence-specific biotinylated (3’) capture probe and fluorescent (5’) reporter probe pairs for each of the representative tyrosine kinase genes (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/zeb) were constructed first. These probe pairs were mixed with 100 ng of total RNA extracted from selected zebrafish developmental stages and the solution was incubated at 65°C for 20 h. After the hybridization of the target mRNA and probe pairs, the excess probes were washed away and the target mRNA-probe pair hybrids purified using the nCounter™ Prep Station followed by detection. Simultaneous detection of all the gene transcripts and controls was performed in multiplexed reactions.54 The raw data were normalized first to the spike controls provided by the manufacturer, and then to two housekeeping genes (hypoxanthine phosphor ribosyl transferase 1, HPRT1 and ribosomal protein L19, RPL19). Two additional housekeeping genes (β-actin, ACTB, and β-glucuronidase, GUSB) were used in the experiment but their values were excluded due to very low counts at certain stages. The spike controls account for variations in hybridizations and purification efficiency. The experiment was done in duplicate and the average of the expression counts were used to infer trends in levels of gene expression. The data were represented as a heat map generated using GENE-E software version 2.0.32 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/index.html).

Results

Based on a combination of profile HMM searches, sequence database searches, pairwise sequence alignments, multiple sequence alignments, and dendrogram construction, we identified the complete set of tyrosine kinase genes encoded by the zebrafish genome and assigned their orthology to human counterparts. Our initial profile HMM searches of the zebrafish RefSeq protein database yielded over 150 hits using default HMMER search parameters. We then proceeded to verify the hits individually using the ENSEMBL, NCBI, and ZFIN databases. We sought to identify gene names and IDs, chromosomal locations and orientations, existing RNASeq data, known mutants, orthology to human genes, and protein sequence similarity. Approximately half of the hits had consistent and accurate information across the three databases above. Information for the other half was missing, incorrect, or inconsistent in one or more of the databases. We chose to use tyrosine kinase sequences we identified in the ENSEMBL database as reference, and used BLAST searches of the ZFIN database to identify existing tyrosine kinase entries or the lack thereof. Our computational analyses led to the identification of 122 distinct tyrosine kinase genes in the zebrafish, with 83 receptor-type organized into 20 families, and 39 nonreceptor type organized into 10 families. In communication with the Sanger Institute and the ZFIN Gene Nomenclature Committee to seek clarification and confirmation of our results, we have suggested modifications to the ENSEMBL and ZFIN databases based on our findings. In naming zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes, we have aimed to ensure consistency with existing human and mouse gene nomenclature, while avoiding conflicts with zebrafish gene nomenclature conventions.

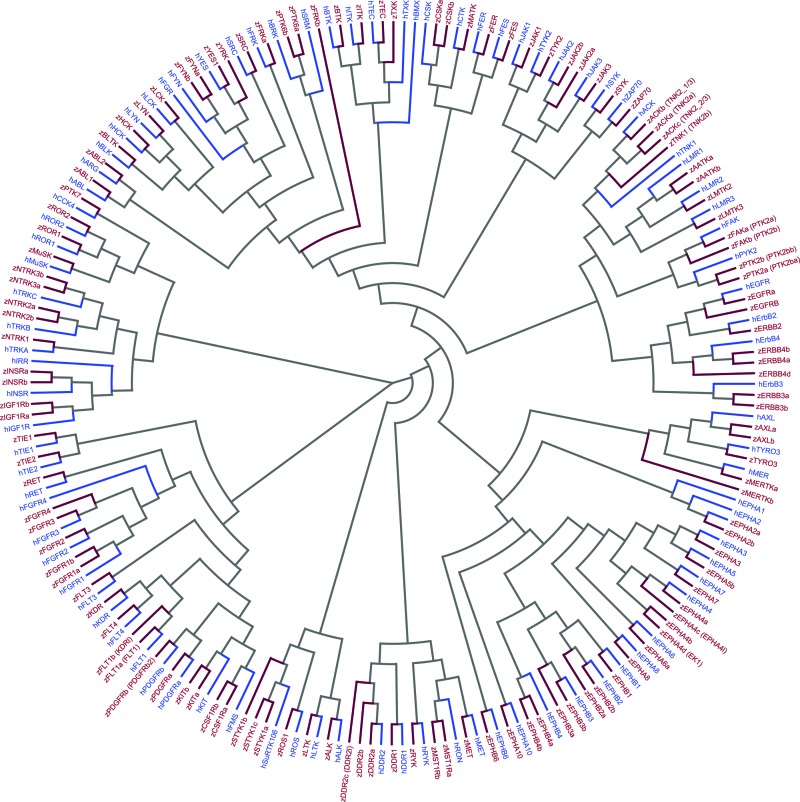

Our results are graphically summarized in a dendrogram (Fig. 1), which is constructed using full-length zebrafish and human tyrosine kinase protein sequences. The dendrogram provides a basis and confirmation of our orthology assignments and shows the clear clustering of zebrafish and tyrosine kinases into identical families. Zebrafish tyrosine kinases can be categorized into 10 nonreceptor tyrosine kinase families and 20 receptor tyrosine kinase families, identical to those in humans. The dendrogram also reveals the fact that each human tyrosine kinase, with the exception of five, has a corresponding zebrafish ortholog. Zebrafish genes yrk and frkb do not have human orthologs, and the human genes bmx, fgr, srm, insrr, and epha1 do not have zebrafish orthologs. While the current version of ENSEMBL shows that the zebrafish gene CH73-340M8.2 (ENSDARG00000040258) is orthologous to the human srm gene (36.3% sequence identity), we suggest that it is related to the human frk gene showing a slightly higher sequence identity score (39.3%) (Supplementary Table S2).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram representing orthologous relationships between the human and zebrafish protein tyrosine kinases. The human genes are prefixed with “h” and the zebrafish genes are prefixed with “z.” Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/zeb

A list of zebrafish tyrosine kinases, their orthologies, and percentage identities to human counterparts is shown in Table 1. The table is classified according to the presence or absence of duplicate zebrafish orthologs. We found that, of the 90 human tyrosine kinases, 55 have an unambiguous zebrafish ortholog, 30 have multiple (66) zebrafish orthologs, and the remaining 5 do not have a zebrafish ortholog. Our study did not find distinct zebrafish orthologs for the human receptor tyrosine kinases EPHA1 and INSRR, and the nonreceptor tyrosine kinases BMX, FGR, and SRM. We also found that the zebrafish tyrosine kinase zYRK which has distinct orthologs in chick and stickleback does not have a human ortholog (Table 1).

Table 1.

Orthology of Zebrafish and Human Tyrosine Kinases with Names, Protein Accession Numbers, and Percentage Sequence Identity of Full-Length Sequences and Kinase Domains

|

Unambiguous Orthology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish gene name | Zebrafish protein accession | Human gene name | Human protein accession | % Sequence identity (full length sequences) | % Sequence identity (kinase domain) |

| erbb2 | ENSDARP00000010252 | erbb2 | ENSP00000269571 | 54.0 | 56.0 |

| pdgfra | ENSDARP00000124752 | pdgfra | ENSP00000257290 | 61.0 | 80.0 |

| pdgfrb (pdgfrb2) | ENSDARP00000028652 | pdgfrb | ENSP00000261799 | 50.0 | 71.0 |

| flt3 | ENSDARP00000075800 | flt3 | ENSP00000241453 | 42.0 | 58.0 |

| fgfr2 | ENSDARP00000124761 | fgfr2 | ENSP00000351276 | 77.0 | 91.0 |

| fgfr3 | ENSDARP00000011898 | fgfr3 | ENSP00000260795 | 77.0 | 88.0 |

| fgfr4 | ENSDARP00000091059 | fgfr4 | ENSP00000292408 | 65.0 | 75.8 |

| flt4 | ENSDARP00000112456 | flt4 | ENSP00000261937 | 54.0 | 64.0 |

| kdr | ENSDARP00000049203 | kdr | ENSP00000263923 | 50.0 | 62.0 |

| met | ENSDARP00000123904 | met | ENSP00000317272 | 51.0 | 81.0 |

| ntrk1 | ENSDARP00000106635 | ntrk1 | ENSP00000357179 | 54.0 | 79.0 |

| epha3 (epha3l) | ENSDARP00000021706 | epha3 | ENSP00000337451 | 80.0 | 87.0 |

| epha5 | ENSDARP00000075583 | epha5 | ENSP00000273854 | 79.0 | 83.0 |

| epha6 | ENSDARP00000121462 | epha6 | ENSP00000374323 | 74.0 | 77.0 |

| epha7 | ENSDARP00000093563 | epha7 | ENSP00000358309 | 86.0 | 94.0 |

| epha8 | ENSDARP00000041799 | epha8 | ENSP00000166244 | 69.0 | 71.0 |

| epha10 | ENSDARP00000064387 | epha10 | ENSP00000362139 | 57.0 | 57.0 |

| ephb1 | ENSDARP00000111570 | ephb1 | ENSP00000381097 | 85.0 | 90.0 |

| ephb6 | ENSDARP00000074926 | ephb6 | ENSP00000410789 | 48.0 | 50.4 |

| tyro3 | ENSDARP00000116623 | tyro3 | ENSP00000263798 | 51.0 | 61.0 |

| alk | ENSDARP00000124055 | alk | ENSP00000373700 | 54.0 | 60.0 |

| ltk | ENSDARP00000062906 | ltk | ENSP00000263800 | 55.0 | 62.0 |

| tie1 | ENSDARP00000124224 | tie1 | ENSP00000361554 | 57.0 | 90.0 |

| tie2 | ENSDARP00000055680 | tie2 | ENSP00000369375 | 51.0 | 90.0 |

| ror1 | ENSDARP00000118145 | ror1 | ENSP00000360120 | 74.0 | 77.0 |

| ror2 | ENSDARP00000101065 | ror2 | ENSP00000364860 | 73.0 | 77.0 |

| ddr1 | ENSDARP00000102505 | ddr1 | ENSP00000427552 | 57.0 | 73.0 |

| ret | ENSDARP00000072093 | ret | ENSP00000347942 | 59.0 | 85.0 |

| ryk | ENSDARP00000106622 | ryk | ENSP00000296084 | 79.0 | 92.0 |

| musk | ENSDARP00000064921 | musk | ENSP00000189978 | 58.0 | 85.0 |

| ros1 | ENSDARP00000118327 | ros1 | ENSP00000357494 | 54.0 | 57.0 |

| lmtk2 | ENSDARP00000098121 | lmtk2 | ENSP00000297293 | 44.0 | 43.0 |

| lmtk3 | ENSDARP00000116726 | lmtk3 | ENSP00000270238 | 56.0 | 57.0 |

| ptk7 | ENSDARP00000089232 | ptk7 | ENSP00000230419 | 64.0 | 72.0 |

| jak1 | ENSDARP00000114784 | jak1 | ENSP00000343204 | 63.0 | 72.0 |

| jak3 | ENSDARP00000049468 | jak3 | ENSP00000432511 | 50.0 | 56.0 |

| tyk2 | ENSDARP00000055123 | tyk2 | ENSP00000431885 | 50.0 | 62.0 |

| abl1 | ENSDARP00000017269 | abl1 | ENSP00000361423 | 69.0 | 62.0 |

| abl2 | ENSDARP00000041696 | abl2 | ENSP00000427562 | 69.0 | 63.0 |

| fer | ENSDARP00000124066 | fer | ENSP00000281092 | 77.0 | 84.0 |

| fes | ENSDARP00000006235 | fes | ENSP00000331504 | 58.0 | 68.0 |

| bltk | ENSDARP00000120039 | blk | ENSP00000406620 | 68.0 | 77.0 |

| lck | ENSDARP00000124901 | lck | ENSP00000328213 | 69.0 | 81.0 |

| lyn | ENSDARP00000040554 | lyn | ENSP00000428924 | 75.0 | 83.0 |

| src | ENSDARP00000093618 | src | ENSP00000362659 | 82.0 | 94.0 |

| yes1 | ENSDARP00000009659 | yes1 | ENSP00000352892 | 85.0 | 95.0 |

| hck | ENSDARP00000115909 | hck | ENSP00000365012 | 75.0 | 86.0 |

| matk | ENSDARP00000104189 | matk | ENSP00000378485 | 63.0 | 67.6 |

| btk | ENSDARP00000124430 | btk | ENSP00000308176 | 63.0 | 72.0 |

| itk | ENSDARP00000022015 | itk | ENSP00000398655 | 59.0 | 65.0 |

| tec | ENSDARP00000106254 | tec | ENSP00000370912 | 68.0 | 77.0 |

| txk | ENSDARP00000092779 | txk | ENSP00000264316 | 55.0 | 66.0 |

| syk | ENSDARP00000122788 | syk | ENSP00000364907 | 65.0 | 76.0 |

| zap70 | ENSDARP00000006727 | zap70 | ENSP00000264972 | 65.0 | 68.0 |

| tnk1 (tnk2b) | ENSDARP00000118604 | tnk1 | ENSP00000312309 | 38.0 | 38.0 |

| egfra | ENSDARP00000121251 | 63.0 | 67.0 | ||

| egfrb | ENSDARP00000110107 | egfr | ENSP00000275493 | 46.0 | 46.0 |

| erbb3a | ENSDARP00000124007 | 49.0 | 47.0 | ||

| erbb3b | ENSDARP00000116216 | erbb3 | ENSP00000267101 | 54.0 | 53.0 |

| erbb4 (5/5) | ENSDARP00000106313 | 71.0 | 71.0 | ||

| erbb4a | ENSDARP00000086551 | 73.0 | 69.0 | ||

| erbb4b | ENSDARP00000116813 | erbb4 | ENSP00000342235 | 83.0 | 79.0 |

| igf1ra | ENSDARP00000017066 | 65.0 | 77.0 | ||

| igf1rb | ENSDARP00000046541 | igf1r | ENSP00000268035 | 63.0 | 79.0 |

| insra | ENSDARP00000023951 | 68.0 | 82.0 | ||

| insrb | ENSDARP00000096601 | insr | ENSP00000303830 | 65.0 | 84.0 |

| csf1ra | ENSDARP00000089365 | 45.0 | 63.0 | ||

| csf1rb | ENSDARP00000121694 | csf1r | ENSP00000286301 | 38.0 | 56.0 |

| kita | ENSDARP00000099069 | 48.0 | 68.0 | ||

| kitb | ENSDARP00000044029 | kit | ENSP00000288135 | 45.0 | 63.0 |

| fgfr1a | ENSDARP00000116533 | 73.0 | 89.0 | ||

| fgfr1b | ENSDARP00000067688 | fgfr1 | ENSP00000380280 | 78.0 | 84.0 |

| flt1a (flt1) | ENSDARP00000002466 | 51.0 | 61.0 | ||

| flt1b (kdrl) | ENSDARP00000007209 | flt1 | ENSP00000282397 | 44.0 | 57.0 |

| mst1ra | ENSDARP00000123874 | 40.0 | 64.0 | ||

| mst1rb | ENSDARP00000124745 | mst1r | ENSP00000296474 | 41.0 | 67.0 |

| ntrk2a | ENSDARP00000078225 | 63.0 | 91.0 | ||

| ntrk2b | ENSDARP00000116694 | ntrk2 | ENSP00000314586 | 60.0 | 86.0 |

| ntrk3a | ENSDARP00000124017 | 73.0 | 89.0 | ||

| ntrk3b | ENSDARP00000086161 | ntrk3 | ENSP00000377990 | 87.0 | 87.0 |

| epha2a | ENSDARP00000011069 | 55.0 | 72.0 | ||

| epha2b | ENSDARP00000044917 | epha2 | ENSP00000351209 | 60.0 | 77.0 |

| epha4a | ENSDARP00000123962 | 82.0 | 88.0 | ||

| epha4b | ENSDARP00000030606 | 66.0 | 77.0 | ||

| epha4c (epha4l) | ENSDARP00000003161 | 74.0 | 77.0 | ||

| epha4d (ek1) | ENSDARP00000096552 | epha4 | ENSP00000386829 | 64.0 | 73.0 |

| mertkb (CU570987.1-201) | ENSDARP00000110210 | 45.0 | 57.0 | ||

| mertka | ENSDARP00000101815 | mer | ENSP00000295408 | 45.0 | 64.0 |

| ephb2a (ephb2) | ENSDARP00000112928 | 86.0 | 90.0 | ||

| ephb2b (ephb2) | ENSDARP00000043755 | ephb2 | ENSP00000383053 | 88.0 | 92.0 |

| ephb3a | ENSDARP00000040208 | 69.0 | 70.0 | ||

| ephb3b | ENSDARP00000050394 | ephb3 | ENSP00000332118 | 81.0 | 91.0 |

| ephb4a | ENSDARP00000111946 | 63.0 | 82.0 | ||

| ephb4b | ENSDARP00000088414 | ephb4 | ENSP00000350896 | 60.0 | 82.0 |

| axla | ENSDARP00000087680 | 53.0 | 54.0 | ||

| axlb | ENSDARP00000087681 | axl | ENSP00000301178 | 59.0 | 59.0 |

| ddr2a | ENSDARP00000124159 | 78.0 | 85.0 | ||

| ddr2b | ENSDARP00000123523 | 66.0 | 73.0 | ||

| ddr2c (ddr2l) | ENSDARP00000124904 | ddr2 | ENSP00000356899 | 58.0 | 69.0 |

| aatka | ENSDARP00000103704 | 60.0 | 58.0 | ||

| aatkb | ENSDARP00000125077 | aatk | ENSP00000324196 | 59.0 | 55.0 |

| styk1a | ENSDARP00000095367 | 44.0 | 44.0 | ||

| styk1b | ENSDARP00000115394 | 32.0 | 35.0 | ||

| styk1c | ENSDARP00000112925 | styk1 | ENSP00000075503 | 36.0 | 41.0 |

| jak2a | ENSDARP00000107572 | 65.0 | 78.0 | ||

| jak2b | ENSDARP00000105218 | jak2 | ENSP00000371067 | 68.0 | 82.0 |

| fyna | ENSDARP00000123888 | 89.0 | 89.0 | ||

| fynb | ENSDARP00000037198 | fyn | ENSP00000346671 | 90.0 | 94.0 |

| cska | ENSDARP00000095046 | 85.0 | 85.0 | ||

| cskb | ENSDARP00000088849 | csk | ENSP00000220003 | 86.0 | 85.0 |

| acka (tnk2a) | ENSDARP00000115160 | 56.0 | 55.0 | ||

| ackb (tnk2(1/3)) | ENSDARP00000109337 | 59.0 | 59.0 | ||

| ackc (tnk2(2/3) | ENSDARP00000084221 | tnk2 | ENSP00000329425 | 56.0 | 55.0 |

| faka (ptk2a) | ENSDARP00000042715 | 81.0 | 84.0 | ||

| fakb (ptk2b) | ENSDARP00000124099 | ptk2 | ENSP00000429911 | 79.0 | 82.0 |

| ptk2a (ptk2ba) | ENSDARP00000036466 | 60.0 | 61.0 | ||

| ptk2b (ptk2bb) | ENSDARP00000057818 | ptk2b | ENSP00000332816 | 60.0 | 63.0 |

| ptk6a | ENSDARP00000063046 | 47.0 | 53.0 | ||

| ptk6b | ENSDARP00000078382 | ptk6 | ENSP00000217185 | 48.0 | 51.0 |

| frka (frk) | ENSDARP00000124324 | 64.0 | 70.0 | ||

| frkb (CH73-340M8.3) | ENSDARP00000058893 | frk | ENSP00000357615 | 39.0 | 45.0 |

|

Unique to Zebrafish | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish gene name | Zebrafish protein accession | Ortholog gene name | Ortholog protein accession | % Sequence identity (full length sequences) | % Sequence identity (kinase domain) |

| yrk | ENSDARP00000121344 | yrk (chicken) | NP_001103257.1 | 77.0 | 89.0 |

|

Unique to Humans | ||

|---|---|---|

| Human Gene Name | Human Protein Accession | |

| epha1 | ENSP00000275815 | |

| srm | ENSP00000217188 | |

| fgr | ENSP00000363117 | |

| bmx | ENSP00000340082 | |

| insrr | ENSP00000357178 | |

Classification according to the presence or absence of duplicate zebrafish orthologs. Names proposed by us are shown with current names in parentheses.

Sequence identities between zebrafish and human tyrosine kinase domains ranged between 95% (yes1) and 35% (styk1b) with an average of 71.5%. Sequence identities for full-length sequences ranged between 90% (fynb) and 32% (styk1b) with an average of 62.6%. A detailed list showing current zebrafish tyrosine kinase gene names and those proposed by us, their ENSEMBL, ZFIN, and VEGA gene IDs, genomic locations (chromosome number and orientation), and mutant alleles is shown in Supplementary Table S3.

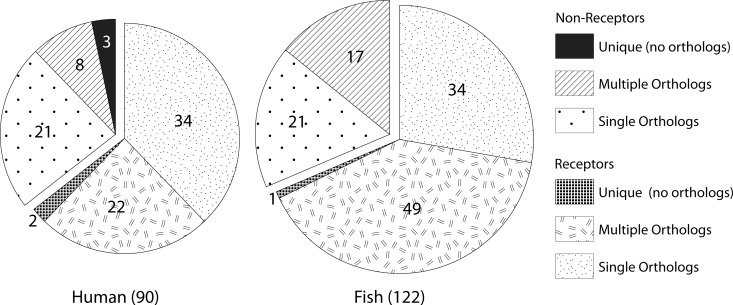

In total, the zebrafish genome encodes 122 tyrosine kinases (containing kinase domains), of which 39 are nonreceptor type and 83 are receptor type. In comparison, the human genome encodes 90 tyrosine kinases with 32 nonreceptor tyrosine kinases and 58 receptor tyrosine kinases. Of the 55 human tyrosine kinases that have single zebrafish orthologs, 21 are nonreceptor and 34 are receptor type, whereas of the 30 human tyrosine kinases with multiple zebrafish orthologs, only 8 are nonreceptor and 22 are receptor tyrosine kinases (Fig. 2). The 8 human nonreceptor tyrosine kinases are represented by 17 zebrafish orthologs, whereas the 22 human receptor tyrosine kinases are represented by 49 zebrafish orthologs. Such gene duplication is in accordance with genome duplication during teleost radiation, but intriguingly, almost three times more duplicate genes appear to be present in receptor tyrosine kinases compared to nonreceptor tyrosine kinases (22 vs. 8 and 49 vs. 17, Fig. 2) in zebrafish.

FIG. 2.

Pie charts showing the numbers of receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases in humans and zebrafish with single and multiple orthologs.

Despite the difference in the actual number of genes, we found further that every human tyrosine kinase family is represented in the zebrafish, suggesting conserved tyrosine kinase evolution in vertebrates. Of all the zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes, only 15 have reported genetic (mutant) alleles (Supplementary Table S2). Thirteen genes do not currently have assigned ZFIN IDs, whereas 16 genes do not currently have assigned VEGA IDs. RNASeq information based on models generated using data from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute zebrafish transcriptome sequencing project (http://www.ensembl.org/info/docs/genebuild/ rnaseq_annotation.html) predicts that almost all zebrafish tyrosine kinases are expressed as early as 1–5 days post-fertilization.

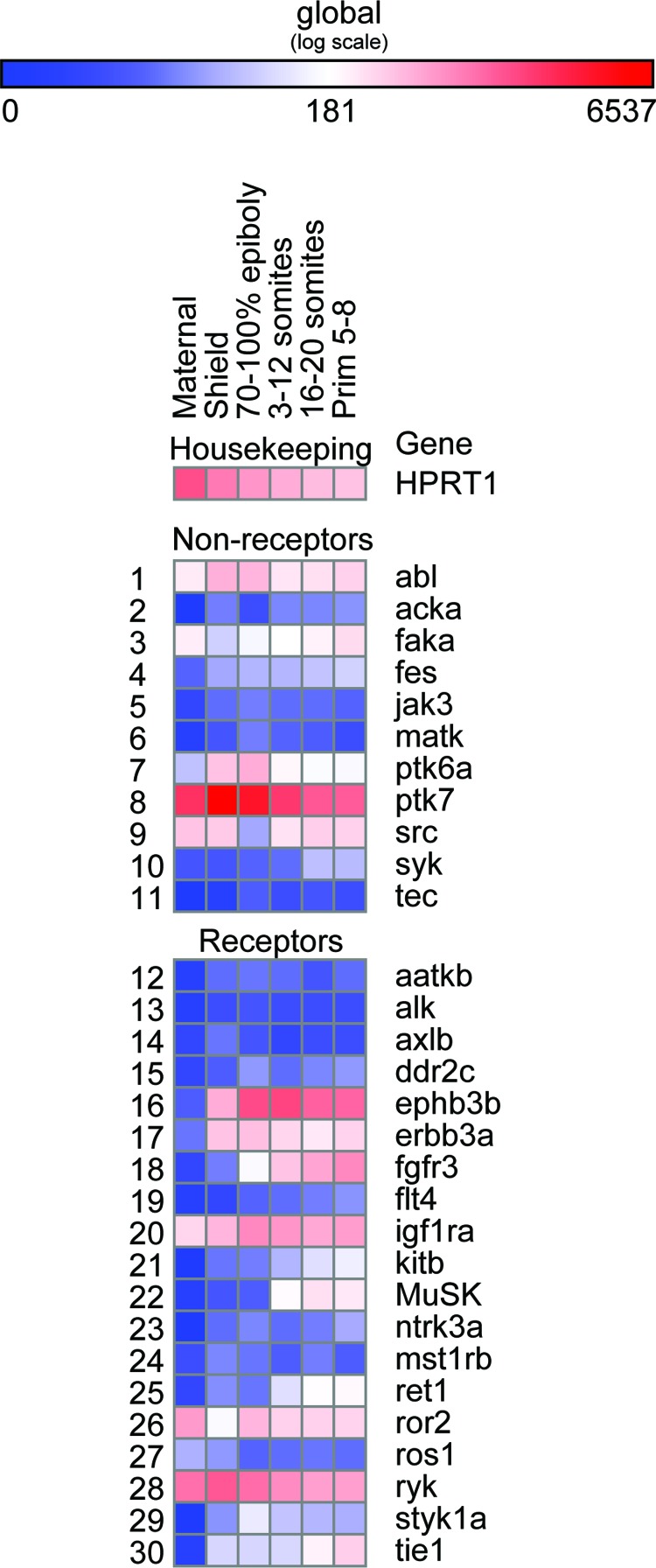

Early expression of zebrafish tyrosine kinases

With the exception of two genes (csf1rb and erbb3a), all other zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes are predicted to be expressed based on the available RNASeq data. In order to generate experimental data to support our computational analysis, we selected a set of 30 tyrosine kinase genes from our list that were either previously unannotated or not reported during the first 24 h of zebrafish development. Direct digital detection using specific probes with the nCounter technology platform allowed us to measure the expression of the selected 30 zebrafish tyrosine kinases representing all families, normalized to that of three housekeeping genes. We found that at specific time points within the first 24 h (24 hpf, hours post fertilization) of development (post-fertilization), 22 (of the 30) tyrosine kinase genes we selected were expressed above the baseline. While 8 genes show minimal expression, PTK7 (CCK4) shows the highest level of expression (Fig. 3). Considering our study and available RNASeq and EST data, csf1rb happens to emerge as the only gene whose expression is not currently reported in zebrafish, and these data are likely to be generated in due course. Our results, in conjuction with Sanger's RNASeq data, strongly suggest that all zebrafish tyrosine kinase families are dynamically expressed and have roles in early embryonic development. Sequences of the specific probes used and normalized expression measurements are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S4, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Gene expression levels of selected tyrosine kinase genes. Nanostring digital readouts for expression levels of nonreceptor and receptor genes are represented by heat map. (HPRT gene is a reference housekeeping gene). The numbered columns represent distinct time windows during the first 24 hours of embryonic development (1=2-cell stage/maternal; 2=shield stage; 3=70% epiboly– bud stage; 4=3–12 somites; 5=16–20 somites; 6=26 somites–Prim 8 stage). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/zeb

Discussion

This study was conducted with the intention of creating an unambiguous resource providing detailed information on zebrafish tyrosine kinases and their relationship to human tyrosine kinases. The information we report is crucial for developmental and genetic studies involving zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes, and for in vivo studies of tyrosine kinase biology using zebrafish. Because of the fact that no such reported study can be found, and that the zebrafish genome annotation is ongoing, our study generated useful annotation data for most of the zebrafish tyrosine kinase genes.

Every human tyrosine kinase family is represented in the zebrafish genome, and mRNA detected in 24 hpf embryos shows that tyrosine kinases from all families are indeed expressed and appear to be regulated. Our analysis further shows that gene duplication, which is known to be common in zebrafish due to whole genome duplication in the teleost lineage, is seen more in receptor tyrosine kinase genes than nonreceptor tyrosine kinase genes. This is consistent with the theory that following genome duplication, gene duplicates which acquired novel functions and contributed to diversity were retained more frequently than others.55 Receptor tyrosine kinases are longer and contain more domains with greater variation than nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that contain fewer and less variant domains. This suggests a greater probability of evolution of novel combinations and functions and therefore greater duplicate gene retention in receptor tyrosine kinases. This explanation is also consistent with the recent discovery of higher divergence among receptor tyrosine kinases during metazoan evolution, which may have facilitated cell-to-cell communication and allowed responses to a variety of extracellular cues during the evolution of multicellularity.56 The same rationale would help explain the retention of a larger tyrosine kinase repertoire compared to that of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases in zebrafish. Future studies to assess these features in other vertebrate lineages will provide a more conclusive explanation of our observation.

A detailed understanding of in vivo effects of tyrosine kinase modulation is needed to achieve a complete mechanistic comprehension of tyrosine kinase biology, and to address current and future issues in tyrosine kinase inhibitor development. Such understanding has been difficult to achieve with the sole use of in vitro biochemical studies, cell culture models, human tissue/clinical studies, or mammalian animal models. It is likely that the probability of success in cancer therapy (or indeed that in any disease) may be enhanced by the use of simpler vertebrate model organisms such as zebrafish57 to model and study disease. For example, understanding the consequences of altered tyrosine kinase activity (by gene overexpression, knockdown/disruption, or small molecule treatment) in the context of a cancer model58,59 in zebrafish will contribute effectively to research in cancer and tyrosine kinase biology.

A major issue with tyrosine kinase inhibitor development is the assessment of their toxicity and safety. The data generated from our study (and such future ones) may facilitate decision-making in toxicity and safety assessment of tyrosine kinase inhibitors by employing zebrafish animal models. We envision that future studies exploring the biochemistry and signaling of zebrafish tyrosine kinases will provide a basis to apply existing or novel kinase assay platforms in zebrafish. The use of zebrafish cancer disease models using strategies of nonspecific tumor generation, tumor xenograft, tumor suppressor knockdown, or oncogene overexpression are likely to lead to in vivo pharmacology models.

Our results also highlight the need to understand individual roles of the tyrosine kinase orthologs in zebrafish development and physiology. The likelihood of multiple active orthologs should be taken into account while designing studies involving tyrosine kinase gene knockdown and disruption, ectopic expression, or small molecule treatment. It should further be noted that the currently annotated version of the zebrafish genome sequence contains unmapped and partial scaffolds. As the zebrafish genome project continues, the quality of sequence information will be greater and gene annotation will be richer. While we believe that our study includes all of the protein tyrosine kinases, new and refined sequence information may result in modifications to our computational findings, with functionally relevant annotations. Revisiting a complete genome sequence of the zebrafish will help to determine if the five exceptions in the list of human and zebrafish tyrosine kinase orthologs we report will remain.

In summary, our findings represent the first comprehensive identification of all zebrafish tyrosine kinases, in which we found remarkably high sequence identity to human tyrosine kinases, identical family classification, and evidence of early developmental expression. Apart from highlighting the need to investigate mechanistic aspects of zebrafish tyrosine kinase biochemistry and physiology, we believe that our study provides strong rational evidence in support of utilizing the zebrafish as an in vivo model organism for future studies on tyrosine kinase biology and pharmacology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Christine Beattie (Department of Neuroscience, The Ohio State University) for access to the zebrafish facility; Dr. Amanda Simcox (Department of Molecular Genetics, The Ohio State University) for making the nCounter gene expression studies possible; Dr. Hansjuerg Alder (OSUCCC-James Nucleic Acid Shared Resource) for the technical support in doing the nCounter experiments; (ZFIN Nomenclature Committee); and Dr. Emma Kenyon (Wellcome Trust Sanger Center) for help with the gene annotation; Dr. Kerstin Howe (Wellcome Trust Sanger Center) for providing valuable information on using the zebrafish genome resources at the Sanger Institute; Yvonne Bradford and Amy Singer (Zebrafish Information Network, University of Oregon) for helping with zebrafish gene nomenclature and modifications to the database based on our recommendations. This work was supported by grant BT/PR13201/Med/30/246/2009 (to K.C. and the Institute of Life Sciences) from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Eckhart W. Hutchinson MA. Hunter T. An activity phosphorylating tyrosine in polyoma T antigen immunoprecipitates. Cell. 1979;18:925–933. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter T. Eckhart W. The discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation: It's all in the buffer! Cell. 2004;116:S35–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00049-2. 1 p following S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sefton BM. Hunter T. Beemon K. Product of in vitro translation of the Rous sarcoma virus src gene has protein kinase activity. J Virol. 1979;30:311–318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.30.1.311-318.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collett MS. Purchio AF. Erikson RL. Avian sarcoma virus-transforming protein, pp60src shows protein kinase activity specific for tyrosine. Nature. 1980;285:167–169. doi: 10.1038/285167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levinson AD. Oppermann H. Varmus HE. Bishop JM. The purified product of the transforming gene of avian sarcoma virus phosphorylates tyrosine. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11973–11980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sefton BM. Hunter T. Beemon K. Eckhart W. Evidence that the phosphorylation of tyrosine is essential for cellular transformation by Rous sarcoma virus. Cell. 1980;20:807–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90327-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Bassat H. Biological activity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Novel agents for psoriasis therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;2:1539–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong WS. Leong KP. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A new approach for asthma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tibes R. Trent J. Kurzrock R. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and the dawn of molecular cancer therapeutics. Ann Rev Pharmacol Therap. 2005;45:357–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.100124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter T. Tyrosine phosphorylation: Thirty years and counting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubbard SR. Crystal structure of the activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in complex with peptide substrate and ATP analog. EMBO J. 1997;16:5572–5581. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sicheri F. Moarefi I. Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature. 1997;385:602–609. doi: 10.1038/385602a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Futterer K. Wong J. Grucza RA. Chan AC. Waksman G. Structural basis for Syk tyrosine kinase ubiquity in signal transduction pathways revealed by the crystal structure of its regulatory SH2 domains bound to a dually phosphorylated ITAM peptide. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:523–537. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brdicka T. Kadlecek TA. Roose JP. Pastuszak AW. Weiss A. Intramolecular regulatory switch in ZAP-70: Analogy with receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4924–4933. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4924-4933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartmann JT. Haap M. Kopp HG. Lipp HP. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. A review on pharmacology, metabolism and side effects. Curr Drug Metab. 2009;10:470–481. doi: 10.2174/138920009788897975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verkhivker GM. Exploring sequence-structure relationships in the tyrosine kinome space: Functional classification of the binding specificity mechanisms for cancer therapeutics. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1919–1926. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li W. Young SL. King N. Miller WT. Signaling properties of a non-metazoan Src kinase and the evolutionary history of Src negative regulation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15491–15501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800002200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manning G. Young SL. Miller WT. Zhai Y. The protist, Monosiga brevicollis, has a tyrosine kinase signaling network more elaborate and diverse than found in any known metazoan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9674–9679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801314105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budi EH. Patterson LB. Parichy DM. Embryonic requirements for ErbB signaling in neural crest development and adult pigment pattern formation. Development. 2008;135:2603–2614. doi: 10.1242/dev.019299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goishi K. Lee P. Davidson AJ. Nishi E. Zon LI. Klagsbrun M. Inhibition of zebrafish epidermal growth factor receptor activity results in cardiovascular defects. Mech Dev. 2003;120:811–822. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojas-Munoz A. Rajadhyksha S. Gilmour D. van Bebber F. Antos C. Rodriguez Esteban C, et al. ErbB2 and ErbB3 regulate amputation-induced proliferation and migration during vertebrate regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009;327:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrios A. Poole RJ. Durbin L. Brennan C. Holder N. Wilson SW. Eph/Ephrin signaling regulates the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition of the paraxial mesoderm during somite morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1571–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julich D. Mould AP. Koper E. Holley SA. Control of extracellular matrix assembly along tissue boundaries via Integrin and Eph/Ephrin signaling. Development. 2009;136:2913–2921. doi: 10.1242/dev.038935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oates AC. Lackmann M. Power MA. Brennan C. Down LM. Do C, et al. An early developmental role for eph-ephrin interaction during vertebrate gastrulation. Mech Dev. 1999;83:77–94. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagle M. Grunewald B. Subburaju S. Barzaghi C. Le Guyader S. Chan J, et al. EphrinB2a in the zebrafish retinotectal system. J Neurobiol. 2004;59:57–65. doi: 10.1002/neu.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma D. Kinsey WH. Fertilization triggers localized activation of Src-family protein kinases in the zebrafish egg. Dev Biol. 2006;295:604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford BD. Henry CA. Clason TA. Becker AL. Hille MB. Activity and distribution of paxillin, focal adhesion kinase, and cadherin indicate cooperative roles during zebrafish morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3065–3081. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry CA. Crawford BD. Yan YL. Postlethwait J. Cooper MS. Hille MB. Roles for zebrafish focal adhesion kinase in notochord and somite morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;240:474–487. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elsen GE. Choi LY. Prince VE. Ho RK. The autism susceptibility gene met regulates zebrafish cerebellar development and facial motor neuron migration. Dev Biol. 2009;335:78–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latimer AJ. Jessen JR. Hgf/c-met expression and functional analysis during zebrafish embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3904–3915. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tallafuss A. Eisen JS. The Met receptor tyrosine kinase prevents zebrafish primary motoneurons from expressing an incorrect neurotransmitter. Neural Dev. 2008;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haire RN. Strong SJ. Litman GW. Tec-family non-receptor tyrosine kinase expressed in zebrafish kidney. Immunogenetics. 1998;47:336–337. doi: 10.1007/s002510050367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lum T. Huynh G. Heinrich G. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and TrkB tyrosine kinase receptor gene expression in zebrafish embryo and larva. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2001;19:569–587. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(01)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jing L. Gordon LR. Shtibin E. Granato M. Temporal and spatial requirements of unplugged/MuSK function during zebrafish neuromuscular development. PLoS One. 5:e8843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golubkov VS. Chekanov AV. Cieplak P. Aleshin AE. Chernov AV. Zhu W, et al. The Wnt/planar cell polarity protein-tyrosine kinase-7 (PTK7) is a highly efficient proteolytic target of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase: Implications in cancer and embryogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35740–35749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.165159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiens KM. Lee HL. Shimada H. Metcalf AE. Chao MY. Lien CL. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta is critical for zebrafish intersegmental vessel formation. PLoS One. 5:e11324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan J. Bayliss PE. Wood JM. Roberts TM. Dissection of angiogenic signaling in zebrafish using a chemical genetic approach. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buchanan CM. Shih JH. Astin JW. Rewcastle GW. Flanagan JU. Crosier PS, et al. DMXAA (Vadimezan, ASA404) is a multi-kinase inhibitor targetting VEGF-R2 in particular. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:449–457. doi: 10.1042/CS20110412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huson DH. Richter DC. Rausch C. Dezulian T. Franz M. Rupp R. Dendroscope: An interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformat. 2007;8:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gjini E. Hekking LH. Kuchler A. Saharinen P. Wienholds E. Post JA, et al. Zebrafish Tie-2 shares a redundant role with Tie-1 in heart development and regulates vessel integrity. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:57–66. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oates AC. Brownlie A. Pratt SJ. Irvine DV. Liao EC. Paw BH, et al. Gene duplication of zebrafish JAK2 homologs is accompanied by divergent embryonic expression patterns: Only jak2a is expressed during erythropoiesis. Blood. 1999;94:2622–2636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christie TL. Carter A. Rollins EL. Childs SJ. Syk and Zap-70 function redundantly to promote angioblast migration. Dev Biol. 2010;340:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mellgren EM. Johnson SL. The evolution of morphological complexity in zebrafish stripes. Trends Genet. 2002;18:128–134. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopes SS. Yang X. Muller J. Carney TJ. McAdow AR. Rauch GJ, et al. Leukocyte tyrosine kinase functions in pigment cell development. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:1000026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlueter PJ. Royer T. Farah MH. Laser B. Chan SJ. Steiner DF, et al. Gene duplication and functional divergence of the zebrafish insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors. FASEB J. 2006;20:1230–1232. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3882fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lemeer S. Jopling C. Naji F. Ruijtenbeek R. Slijper M. Heck AJ, et al. Protein-tyrosine kinase activity profiling in knock down zebrafish embryos. PLoS One. 2007;2:e581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lemeer S. Pinkse MW. Mohammed S. van Breukelen B. den Hertog J. Slijper M, et al. Online automated in vivo zebrafish phosphoproteomics: From large-scale analysis down to a single embryo. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1555–1564. doi: 10.1021/pr700667w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pruitt KD. Tatusova T. Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): A curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D61–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eddy SR. A new generation of homology search tools based on probabilistic inference. Genome Inform. 2009;23:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marchler-Bauer A. Anderson JB. Chitsaz F. Derbyshire MK. DeWeese-Scott C. Fong JH, et al. CDD: Specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D205–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimmel CB. Ballard WW. Kimmel SR. Ullmann B. Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geiss GK. Bumgarner RE. Birditt B. Dahl T. Dowidar N. Dunaway DL, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato Y. Hashiguchi Y. Nishida M. Temporal pattern of loss/persistence of duplicate genes involved in signal transduction and metabolic pathways after teleost-specific genome duplication. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suga H. Dacre M. de Mendoza A. Shalchian-Tabrizi K. Manning G. Ruiz-Trillo I. Genomic survey of premetazoans shows deep conservation of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases and multiple radiations of receptor tyrosine kinases. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra35. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alberts B. Redefining cancer research. Science. 2009;325:1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1181224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Etchin J. Kanki JP. Look AT. Zebrafish as a model for the study of human cancer. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;105:309–337. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao C. Wang X. Zhao Y. Li Z. Lin S. Wei Y, et al. A novel xenograft model in zebrafish for high-resolution investigating dynamics of neovascularization in tumors. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.