Abstract

The Mississippi Delta region is one of the communities most heavily impacted by HIV/AIDS in the United States. To understand local provider attitudes and practices regarding HIV testing and care, we conducted 25 in-depth qualitative interviews with local primary care providers and infectious disease specialists. Interviews explored attitudes and practices regarding HIV testing and linkage to care. Most providers did not routinely offer HIV testing, noting financial barriers, financial disincentives to offer routine screening, misperceptions about local informed consent laws, perceived stigma among patients, and belief that HIV testing was the responsibility of the health department. Barriers to enhancing treatment and care included stigma, long distances, lack of transportation, and paucity of local infectious disease specialists. Opportunities for enhancing HIV testing and care included provider education programs regarding billing, local HIV testing guidelines, and informed consent, as well as telemedicine services for underserved counties. Although most health care providers in our study did not currently offer routine HIV testing, all were willing to provide more testing and care services if they were able to bill for routine testing. Increasing financial reimbursement and access to care, including through the Affordable Care Act, may provide an opportunity to enhance HIV/AIDS services in the Mississippi Delta.

Introduction

An estimated 1.1 million individuals live with HIV in the United States.1 New HIV infections are increasingly concentrated in non-metropolitan communities, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), using the Office of Management and Budget's criteria of having a population less than 50,000.2,3 African Americans represent 45% of new AIDS diagnoses, and 48% of new HIV infections in nonmetropolitan areas nationwide.4 Non-metropolitan regions in the Northeast, West, and Midwest have new AIDS cases diagnosed at rates of 4.6, 3.4, and 2.5 per 100,000 people, respectively. By contrast, the non-metropolitan South has an AIDS diagnosis rate of 8.2 per 100,000 people.4

African Americans are disproportionately impacted by HIV; they have seven times the rates of White Americans.1 Although African Americans represent 14% of the total US population, they account for 44% of new HIV infections in the United States.5 Behavioral risk factors commonly associated with HIV transmission including condom use, drug use, and number of lifetime sexual partners, do not fully explain disparities in HIV infection rates between African Americans and Whites.6 Additionally, African Americans are significantly more likely to present for testing and care late in the course of their HIV infection.7

Mississippi has among the widest racial disparities in HIV infection of any state in the country; while African Americans represent only 37% of the state population, they comprised 77% of new AIDS cases in 2009.4 Moreover, while new HIV cases in Mississippi increased only 6% overall from 2005 to 2009, new HIV cases among African Americans rose by 32%.8 In 2010, Mississippi ranked 9th in the nation in new HIV diagnosis rates, with an estimated rate of 19.1 per 100,000.3 A recent CDC report lists Jackson, Mississippi as the metropolitan area with the third highest rate of people living with an AIDS diagnosis in the US.7 Notably, 47% of Mississippians diagnosed with HIV in 2010 reported no identifiable transmission risk.2 Over 50% of HIV-positive individuals in Mississippi are not in care.9 Moreover, in a study among HIV-positive individuals recently linked to care in Mississippi, average CD4 counts were low, suggesting that many people test HIV positive late in the course of their disease; many are concurrently diagnosed with AIDS.10 These findings suggest there is unmet need for HIV testing and treatment in Mississippi.

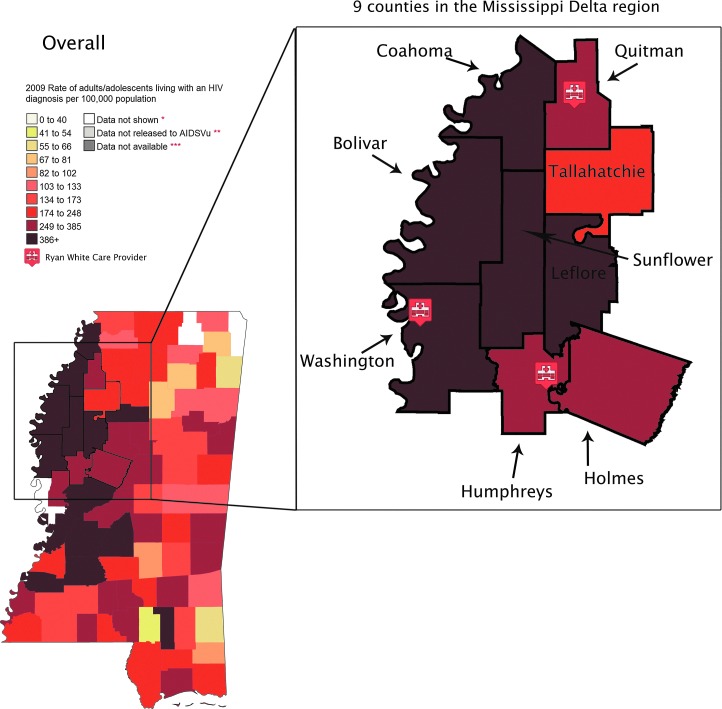

The Mississippi Delta constitutes the northwest section Mississippi that lies between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. The region is one the most economically disadvantaged and medically underserved regions of the country11 and also has among the nation's widest racial disparities in HIV infection.12 The rate of HIV diagnosis in the Mississippi Delta region is 17.3 per 100,000; this is the highest diagnosis rate of any non-metropolitan area outside of the US/Mexican border region12 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

2009 Rate of individuals living with HIV by county in the Mississippi Delta area. (Color image can be found at www.liebertonline.com/apc).

Since 2006, the CDC has recommended routine annual HIV testing for all Americans ages 13–65 years;13 these guidelines have been endorsed by the American College of Physicians, the Infectious Disease Society of America, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.14,15 Despite these recommendations, most health care providers do not routinely offer HIV testing to their patients.16 Recent research highlights provider17,18 and patient19–21 barriers to HIV testing in the United States. However, little is known about providers' perspectives and practices related to routine HIV testing and linkage to care in the rural South, and in the Mississippi Delta in particular. To better understand provider attitudes and practices about routine HIV testing and linkage to HIV/AIDS care, we conducted a qualitative study among 25 primary care providers and infectious disease specialists in the Mississippi Delta.

Methods

We conducted qualitative interviews with 25 healthcare providers from the Mississippi Delta during 2012. Providers included nurse practitioners and physicians practicing in primary care and infectious disease specialty clinics in nine Mississippi Delta counties, including Bolivar, Coahoma, Holmes, Humphreys, Leflore, Sunflower, Tallahatchie, Quitman, and Washington counties. We recruited participants using several methods. First, we called individuals from the Mississippi Primary Healthcare Association website directory. We also recruited contacts from the Mississippi Center for Justice network, a local nonprofit organization. We used snowball sampling to recruit the remainder of participants.

Study inclusion criteria included being a primary or infectious disease healthcare provider serving patients in the Delta, ability to provide informed consent, and ability to speak English. Participants had to be willing to participate in one or two qualitative interviews concerning their attitudes and practices about routine HIV testing, perceived barriers, and opportunities for enhancing HIV testing and HIV/AIDS treatment and linkage to care.

Interviews were 1–2 h in length and included questions regarding attitudes about the local HIV/AIDS epidemic, current HIV testing practices, personal beliefs about routine HIV testing, beliefs about the impact of testing on the staff and patient population, racial disparities in HIV infection rates, and recommendations for enhancing linkage to care for individuals who tested positive. Interviews were loosely structured and included as many open-ended questions as possible to allow for flexibility in response and for introduction of topics by both the interviewer and participants.22,23 We conducted interviews until we reached saturation, or when no new data were emerging.

All interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. Identifying information was removed from transcripts, which were coded by patterns and themes emerging from the data. An open coding process allowed researchers to group themes according to topics that arose during the interviews.22,24 Rather than code individual ideas independently of context, we adopted a “contextualizing strategy” in coding and analyzing the interviews.25,26 To help ensure the reliability and validity of the study findings, all interviews were coded by more than one data analyst, and codes were checked for concordance. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved among the research team. Analytic memos were drafted to summarize key findings of each interview and to systematically link important ideas and themes between respondents; these memos informed study findings.

Results

We interviewed four Ryan White Care providers, five providers from federally qualified health centers, and 16 primary care providers in private practice, for a total of 25 providers from 18 distinct medical institutions. To our knowledge, this included all Ryan White care providers in the region. Only two of the providers whom we contacted refused an interview; four others did not respond to interview requests. Seventeen of the providers were medical doctors, and eight were nurse practitioners. Nine counties in the Mississippi Delta region were represented. Fifteen providers were Caucasian, six were African American, one was Asian American, and three were from overseas. Table 1 summarizes our primary findings.

Table 1.

Barriers and Opportunities to Routine HIV Testing and Linkage to Care in the Mississippi Delta

| Theme | Major findings |

|---|---|

| Provider and patient knowledge about HIV/AIDS in the Delta region | Most providers understood the gravity of local epidemic and racial disparities in HIV infection; a few were unaware of local HIV infection rates. |

| Providers perceived that their patients may underestimate their own HIV risks. | |

| Current HIV testing practices | Most primary care providers do not routinely offer HIV testing to patients. |

| All Ryan White care providers offered routine HIV testing. | |

| Barriers to routine HIV testing | Lack of knowledge about appropriate reimbursement procedures inhibits routine HIV testing offer. |

| Lack of knowledge about Mississippi laws governing informed consent for HIV testing inhibits routine HIV testing offer. | |

| Providers believe most of their patients had low self-perceived HIV risk that could inhibit HIV testing. | |

| Opportunities for enhancing routine HIV testing | Most providers were receptive to routine HIV testing. Providers requested training on appropriate billing in context of Affordable Care Act and USPSTF recommendations. |

| Social marketing could increase demand for and destigmatize HIV testing and treatment. | |

| Barriers to linkage to treatment and care | Stigma inhibits uptake of existing treatment and care services. |

| The Mississippi Delta is a medically underserved community with few HIV care providers. | |

| Patients must travel great distances for treatment and care services. | |

| Opportunities for enhancing HIV treatment and care | Infectious disease specialists could provide care through telemedicine services from Jackson, MS |

| More HIV/AIDS care services at public clinics and federally qualified health centers in the region. |

Knowledge about the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Mississippi Delta

The majority of providers acknowledged the gravity of the local epidemic. Many noted the overwhelming stigma associated with HIV/AIDS in Mississippi, and general lack of public awareness about the epidemic, particularly among the most heavily impacted populations. Most providers understood the region's wide racial disparities in HIV infection.

Just from what I read, it says African Americans are more affected. Of course our population is seventy-five percent African American anyway…So they're going to be the majority of anything we have…Whether it's high blood pressure, or diabetes, or heart trouble, kidney failure. They're the majority of everything we have, because they're the majority of the people.

On the other hand, a few providers were unaware of the high rates of infection in the Delta region. Several commented:

It's amazing that we've controlled the epidemic…

I have not seen a lot of HIV here.

Even though we're seeing a good bit of syphilis, we rarely see an HIV case. We don't understand that. You know, 10 years ago, we predicted that the Mississippi Delta would be the AIDS capital of the world because of our high level of sexually transmitted diseases, but it hasn't turned out that way. I don't understand and I don't think any of us understand why, in a place with so many sexually transmitted diseases, the HIV rates are relatively low in the Delta.

Current practices

Other than Ryan White Care providers, none of the providers (n=21) participating in the study routinely offered HIV testing to their patients; rather, most providers reported offering HIV testing based on behavioral risk profiles, and only offered HIV testing to patients they perceived to be at high-risk. A provider explained this common practice:

You wouldn't want to do it on everybody that walks in for their annual. You wouldn't necessarily say let's go get an HIV test if they've been married for 30 years and no history of anything else.

We talk about high-risk sexual behavior. And we talk about screening tests and HIV is one of those screening tests. And we do have on our bulletin boards information on HIV that alert people that they can have an HIV test done.

However, all of the four Ryan White care providers offered HIV testing routinely to all patients. One Ryan White care provider explained:

I offer it to my primary care patients. At least once a year. We truly believe that when it's empowering that you leave here knowing your status. We encourage them to bring partners in. We encourage them to get regular testing or if they have questionable incidents in their lives, to come back and be tested again. It works for us. So regardless of age, gender, sexual preference, we offer testing.

Barriers to routine testing

Providers noted several barriers to offering routine HIV testing. These included inability to bill for HIV testing, confusion about local laws governing informed consent, and low perceived risk of acquiring HIV among their patients.

Reimbursement

Insufficient reimbursement for HIV screening was the most commonly cited barrier to routine HIV testing. Two physicians noted:

The barrier is as follows: if I'm insured, insurance won't pay for it. Medicaid won't pay for it. And our clinic can't eat that cost. I mean it's not financially responsible to do that.

This is one of the ten poorest counties in the nation. This isn't Minneapolis. And the government will make a lot of recommendations. But then they don't fund those recommendations!

A few other providers mentioned they did not routinely test because they didn't understand whether and how they'd be reimbursed:

And see, that's why I haven't tested often, because I don't know what the reimbursement rate is.

Understanding local informed consent laws

Although Mississippi law no longer requires separate written informed consent for HIV testing, many providers misunderstood local laws about informed consent, and noted they would welcome further guidance from the Mississippi State Department of Health about Mississippi laws governing HIV testing consent. One nurse practitioner noted that her clinic still requires written consent for HIV testing:

When we do an HIV test, we get the patients to sign a consent form that says that they're consenting to the test. Why do we do that if it's not the current standard of care? Years ago, you had to get their permission to do it. Is that still the standard of care? Don't you have to get their written consent?

Another provider commented:

Prior to the test, they sign a consent. I don't even think the written consent is needed anymore, but we still ask them to sign it. I think the Mississippi Health Department still recommends it.

Low perceived risk among patients

Many providers reported that despite very high local infection rates, most of their patients, including those at highest risk, perceived their own risk for acquiring HIV as low; this was an important barrier to routine testing. This problem was particularly challenging among providers with many middle-aged and elderly patients:

I couldn't sit in here with my regular patients and say I think I'll check you for HIV too. They would just freak out, because you know, they're not going to think they have it. I wouldn't even bring it up to my patients!

Additionally, there was a common misperception that the health department was responsible for conducting all HIV testing in the region. One physician explained:

We talk about routine testing, but I'm going to let the health department do that. I defer a lot to them now because they're so good at it. And they do it very economically. We have a very good health department, believe it or not.

Opportunities for enhancing routine HIV testing and linkage to care

In spite of the aforementioned barriers to implementing routine testing in the Delta, nearly all the providers explained they would be willing to offer routine HIV testing if they were able to bill for the service. Two physicians explained this common sentiment:

If I can break even and nothing's going to come out of the patient's pocket, I'd do HIV tests all day! Because any screening and preventive medicine we can practice– by exam or lab test– I'm all for it.

In addition, several providers requested more information on how to appropriately bill for HIV testing.

Linkage to care

Most providers reported seeing few HIV/AIDS patients. Most believed that enhancing linkage to care among people living with HIV in the Mississippi Delta depended on addressing the overwhelming stigma associated with HIV/AIDS. A provider explained this nearly universal sentiment:

…still in this day, and time, and this age, there's still a lot of stigma associated with the diagnosis of HIV disease. And still today with all of the technology, all of the information, it's [HIV] very, very poorly understood particularly by the people who are affected by it and by far now, the people who are most affected by it are the people who know the least about healthcare or who seek healthcare the least.

Providers also offered suggestions for how to enhance linkage and retention in HIV/AIDS care. Several providers noted the need for integrating more HIV/AIDS care services into local community health centers or federally qualified health centers rather than relying exclusively on Ryan White care clinics:

At one point we really had a chance to get on top of HIV/AIDS, but the funding basically dried up and then when there was available funding…I think it was put in a lot of the wrong places, like very few community health centers got the Ryan White type money to do HIV and AIDS care. A lot of the patients just didn't want to go to those providers, because everyone's believes this is the AIDS clinic and if I'm there, they must know that I'm here for that. The same thing with the health department, you know, if you went to the health department, you know, it was either treated for STDs or HIV/AIDS. And the places where those patients were already patients were able to assume their care and integrate it with whatever else they were coming to the health center for. They were kind of shut out and left out of that picture. So consequently, they lost a lot of those patients who could have been in care.

A commonly cited barrier to enhancing linkage to care in the Mississippi Delta was a perception among providers that it would be very difficult to attract and retain primary care or infectious disease physicians willing able to provide HIV/AIDS care. One physician commented:

There are not many people willing to move to the Delta and work in a low paying primary care position at a community health center. I think in theory it's a great idea, but I don't think in practice it would ever happen. You might get one here and one there, it will be very patchy. I think you're going to do better identifying primary care physicians in the area that are interested in that kind of care and then linking them with someone in a center or having an internal medicine infectious disease specialist visit those areas.

Citing the great distances many patients must travel in the Delta region and the paucity of infectious disease specialists in the area, several providers also mentioned that telemedicine might reduce patient travel burden and enhance linkage to care.

Telemedicine has a role. That might be the linkage. You see the patient, you maybe get specialized training to do some of the care and then you have access to telemedicine too and an infectious disease specialist who has cutting edge recommendations. That might be an easier way to encompass the total care under one roof.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies among medical providers about HIV testing and care practices in the Mississippi Delta, one of the most heavily impacted, medically underserved communities of the United States.12 Many providers were aware of high HIV infection rates in the Mississippi Delta and noted several social and structural factors that contribute to high infection rates, including low perceived risk, stigma that inhibits testing and treatment, poverty, and limited access to health services. On the other hand, some providers were unaware of the gravity of the local epidemic and racial disparities in HIV infection and care in particular. Most providers believed their patients were unaware of the high rates of HIV infection in the Mississippi Delta. These findings suggest a need for interventions such as education and social marketing campaigns to destigmatize and increase demand for local testing and treatment services.

With the exception of local Ryan White clinicians, none of the providers in our sample routinely tested their patients for HIV. In primary care clinics, most providers offered HIV tests based on patients' self-perceived risk or their own perception of patients' HIV risk. Because patients and providers often underestimate or miscalculate patient risk for HIV acquisition, risk based screening is an insensitive criterion for diagnosing the nearly 20% of HIV-positive Americans who do not know their status.27–29 Routinizing HIV testing in primary care clinics could also help destigmatize HIV testing in this heavily impacted community with limited access to health services. Additionally, these findings suggest that there is great opportunity for targeted education and support to healthcare providers to enhance implementation of routine HIV screening and effective linkage to care. A comprehensive program to train providers should include professional organizations, health care associations and the Mississippi State Department of Health.

Notably, most providers stated they would be willing to offer routine HIV testing if they were able to bill for it. In April 2013, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released new guidelines that recommend routine HIV testing for all adults aged 15–65 years.30 This new recommendation and “A” grade for testing will allow health care providers to bill Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers for routine HIV testing more readily. Previously, in spite of CDC guidelines recommending routine HIV testing,31 most major insurance agencies and governmental programs only reimbursed providers for HIV testing if they or their clients believed they were at high-risk for contracting HIV.32 Previously, USPSTF “B” rankings for HIV testing created strong financial incentives for risk-based rather than routine HIV screening. Our findings suggest that this important policy change will provide opportunities for increased testing in the Mississippi Delta, where most of the providers we interviewed noted they would be willing to provide testing if they were able to bill for it. Many of the providers in our sample also requested technical assistance with billing practices related to HIV testing.

Additionally, many providers mistakenly believed that Mississippi law still requires separate informed consent for HIV testing, and cited this as a barrier to implementing routine testing. Current Mississippi law does not require separate written informed consent for HIV testing. This, coupled with our findings that providers are willing to provide routine testing, suggests it may be important to educate local providers about the USPSTF policy change, how to bill major payers for HIV testing, and local laws governing informed consent related to HIV testing. Providing health care providers with training on local informed consent guidelines and appropriate billing practices in the context of the Affordable Care Act presents an important public health opportunity for reducing racial disparities in HIV/AIDS testing and treatment services in the Mississippi Delta region.

The most commonly cited impediments to linking patients to HIV treatment and care services were insufficient treatment and care services in the area, along with the overwhelming stigma associated with HIV/AIDS in the Mississippi Delta. Providers believed that more treatment and care services should be integrated into primary care practices to reduce patient travel burden. There may also be opportunity to integrate HIV testing into Emergency Department intake programs, as Mississippi has a primary health care provider shortage and high Emergency Department use.33 HIV testing programs in Emergency Departments have been used successfully to identify new HIV cases in other southern settings.34 Emergency Department testing might also be an important means to expand HIV testing services in the Mississippi Delta; other studies find emergency rooms may provide opportunities to link patients to treatment and care services who otherwise would not have been tested because they lack health insurance or primary care providers.35–37

Additionally, telemedicine has been used successfully in other settings for HIV/AIDS care,38–40 and for primary care in the Delta region; those programs may offer important lessons for enhancing treatment and care in the Delta. Formal partnerships for referrals and other technical assistance with experienced HIV care providers in other parts of Mississippi could also enhance HIV testing and care practices in the Mississippi Delta region.

HIV testing, treatment, and retention-in-care are critical components for reducing racial disparities in HIV infection. Individuals who test HIV-positive reduce their risk taking behaviors.27 HIV-positive individuals who adhere to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) have lower HIV viral loads, slower HIV disease progression,41 and dramatically lower odds of transmitting HIV to uninfected sexual partners.42 The HIV care cascade commences with HIV screening that can enhance early diagnosis, entry, and retention-in-care, with an end goal of long-term suppression of HIV viremia. Although HIV treatment reduces the probability of HIV transmission to others, less than 30% of HIV-infected individuals have suppressed viral RNA.43 African Americans have poorer outcomes at every stage of the continuum of HIV/AIDS care; only 21% of African Americans living with HIV have suppressed viral RNA, compared to 30% of Whites.44 Improving these disparities will require intervening at every point in the cascade, which starts with HIV diagnosis; focusing intense efforts on enhancing testing and treatment in the most heavily impacted communities in the country is important for addressing disproportionately high rates of HIV infection in Mississippi.

There are several limitations to this study. This study is based on a sample of providers in the Mississippi Delta and the findings may not be generalizable to other settings. However, there may be important lessons for other similar Southern settings with wide disparities in HIV/AIDS outcomes and limited health infrastructure. While a 1–2 hour interview may have deterred some providers from participating, overall we had very high participation rates and reached a large number of all primary care providers in the region.

Our findings suggest that in spite of current limited HIV testing practices in the Mississippi Delta, providers are overwhelmingly willing to offer HIV testing routinely if they are able to be reimbursed. The Affordable Care Act and new USPSTF guidelines that will facilitate provider reimbursement for testing32 provide an opportunity to increase HIV testing dramatically in one of the most heavily impacted and medically underserved areas of the country. Expanding routine HIV testing and linkage to care is critical for reducing racial disparities in HIV infection and care in Mississippi.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported with NIH Grants K01020228-01A1, K23AI096923, P01AA019072, and P30-AI-42853, a Brown University Alpert Medical School Summer Assistantship, and a grant from the MAC AIDS Fund.

Map Source: AIDSVu (www.aidsvu.org). Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health. May 7, 2013.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Amy Nunn, Dr. Philip Chan, and Dr. Leandro Mena receive grant support from Gilead Science, Inc. HIV Focus Program. Amy Nunn receives consulting fees from Mylan, Inc.

References

- 1.Hall HI. Song R. Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MSDH. Jackson; Mississippi: 2008. Mississippi State Department of Health HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Centers for Disease Control; 2010. iagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.HIV Disease 2011 Fact Sheet for Mississippi. Jackson, MS: Mississippi Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman SR. Cooper HL. Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallfors DD. Iritani BJ. Miller WC. Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: The need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. Centers for Disease Control; 2011 2010.

- 8.MSDH. In: Health MSDo. Jackson; Mississippi: 2009. Mississippi State Department of Health HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amy Rosenberg EB. Rachel Mehlsak SC. Robert Greenwald., editor. Mississippi State Report. State Healthcare Access Resarch Project. 2010.

- 10.Arti Barnes LM, et al. Mississippi 2010 MMP Fact Sheet; 4/6/2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poverty in Rural America. Housing Assistance Council; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall HI. Li J. McKenna MT. HIV in predominantly rural areas of the United States. J Rural Health. 2005;21:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC. Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das M. Volberding P. Bringing the end in sight: Consensus regarding HIV screening strategies. Ann Int Med. 2013;159:63–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moyer VA. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;51:301–303. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartlett JG. Branson BM. Fenton K. Hauschild BC. Miller V. Mayer KH. Opt-out testing for human immunodeficiency virus in the United States: Progress and challenges. JAMA. 2008;300:945–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirreffs A. Lee DP. Henry J. Golden MR. Stekler JD. Understanding barriers to routine HIV screening: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare providers in King County, Washington. PLoS One. 2012;7:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korthuis PT. Berkenblit GV. Sullivan LE, et al. General internists' beliefs, behaviors, and perceived barriers to routine HIV screening in primary care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:70–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arya M. Kallen MA. Williams LT. Street RL. Viswanath K. Giordano TP. Beliefs about who should be tested for HIV among African American individuals attending a family practice clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:1–4. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arya M. Patuwo B. Lalani N, et al. Are primary care providers offering HIV testing to patients in a predominantly Hispanic community health center? An exploratory study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:256–258. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarcz S. Richards TA. Frank H, et al. Identifying barriers to HIV testing: Personal and contextual factors associated with late HIV testing. AIDS Care. 2011;23:892–900. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.534436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merriam SB. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pranee Liamputtong Rice DE. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss RS. Learning from Strangers: The Art of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. London: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks G. Crepaz N. Senterfitt JW. Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinhardt LS. Carey MP. Johnson BT. Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunn A. Zaller N. Cornwall A, et al. Low perceived risk and high HIV prevalence among a predominantly African American population participating in Philadelphia's Rapid HIV testing program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:229–235. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Force UPT. Screening for HIV. 2013.

- 31.CDC. Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. 2006. [PubMed]

- 32.Martin EG. Schackman BR. Updating the HIV-testing guidelines—A modest change with major consequences. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:884–886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1214630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman IB. Clark S. Sullivan AF. Camargo CA., Jr. National study of the relation of primary care shortages to emergency department utilization. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:279–282. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheatley MA. Copeland B. Shah B. Heilpern K. Del Rio C. Houry D. Efficacy of an emergency department-based HIV screening program in the Deep South. J Urban Health. 2011;88:1015–1019. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bamford L. Ellenberg JH. Hines J. Vinnard C. Jasani A. Gross R. Factors associated with a willingness to accept rapid HIV testing in an urban Emergency Department. AIDS Behav. 2013;28:28. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0452-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankoff J. Hopkins E. Sasson C. Al-Tayyib A. Bender B. Haukoos JS. Payer status, race/ethnicity, and acceptance of free routine opt-out rapid HIV screening among emergency department patients. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:877–883. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reichmann WM. Walensky RP. Case A, et al. Estimation of the prevalence of undiagnosed and diagnosed HIV in an urban emergency department. PLoS One. 2011;6:16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caceres C. Gomez EJ. Garcia F. Gatell JM. del Pozo F. An integral care telemedicine system for HIV/AIDS patients. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75:638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saifu HN. Asch SM. Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldura JF. Neff S. Dehlendorf C. Goldschmidt RH. Teleconsultation improves primary care clinicians' confidence about caring for HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;1:1. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinn TC. Wawer MJ. Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen MS. Chen YQ. McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardner EM. McLees MP. Steiner JF. Del Rio C. Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall HI. Continuum of HIV care: Differences in care and treatment by sex and race/ethnicity in the United States. Paper presented at: International AIDS Conference 2012; Washington DC. [Google Scholar]