Abstract

Prostate cancer represents approximately 10 percent of all cancer cases in men and accounts for more than a quarter of all cancer types. Advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of prostate cancer progression, however, have not translated well to the clinic. Patients with metastatic and hormone-refractory disease have only palliative options for treatment, as chemotherapy seldom produces durable or complete responses, highlighting the need for novel therapeutic approaches. T-oligo, a single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid with partial sequence homology to human telomeric DNA, has elicited cytostatic and/or cytotoxic effects in multiple cancer cell types. In contrast, normal primary cells of varying tissue types are resistant to cytotoxic actions of T-oligo, underscoring its potential utility as a novel targeted cancer therapeutic. Mechanistically, T-oligo is hypothesized to interfere with normal telomeric structure and form G-quadruplex structures, thereby inducing genomic stress in addition to aberrant upregulation of DNA damageresponse pathways. Here, we present data demonstrating the enhanced effectiveness of a deoxyguanosine-enriched sequence of T-oligo, termed (GGTT)4, which elicits robust cytotoxic effects in prostate cancer cells at lower concentrations than the most recent T-oligo sequence (5′-pGGT TAG GTG TAG GTT T 3′) described to date and used for comparison in this study, while exerting no cytotoxic actions on nontransformed human prostate epithelial cells. Additionally, we provide evidence supporting the T-oligo induced activation of cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling in prostate cancer cells consistent with G-quadruplex formation, thereby significantly advancing the understanding of the T-oligo mechanism of action.

Introduction

Prostate cancer represents approximately 10 percent of all cancer cases in men; second only to cancers of the lung and bronchus. The estimated number of new cases in the past year in the United States is 240,890, representing more than a quarter of all cancer types. (Siegel et al., 2011) Treatment modalities are largely limited to surgical resection of malignant tissue, radiotherapy, and androgen ablation. Between 10% and 20% of patients present with advanced metastatic disease. In nearly all cases, treatment via androgen ablation results in androgen-independent disease between 18 and 24 months after starting treatment. Despite advancing knowledge regarding the molecular mechanisms of prostate cancer progression, patients with metastatic and hormone-refractory disease have only palliative options for treatment, and chemotherapy seldom produces durable or complete responses (Garcia et al., 2011; George et al., 2012). Recent clinical trials testing treatment regimens combining novel taxane cytotoxic agents with hormone therapy increased median survival by only months (Petrylak et al., 2004; Tannock et al., 2004). Advanced disease is ultimately fatal in patients within ten to eighteen months, (Petrylak et al., 2004; Tannock et al., 2004), underscoring the need for novel therapeutic approaches (Garcia et al., 2011; George et al., 2012).

T-oligo, a single-strand DNA oligonucleotide with partial sequence homology to human telomeric DNA, has demonstrated cytostatic and/or cytotoxic effects in multiple cancer cell types (Eller et al., 2002; Li et al., 2003; Aoki et al., 2007; Longe et al., 2007; Yaar et al., 2007; Longe et al., 2009; Rankin et al., 2011), at concentrations of 40 μM or less, while failing to elicit toxic effects in normal primary cells, including mammary epithelial cells (Yaar et al., 2007), astrocytes (Aoki et al., 2007), and B-cell lymphocytes (Longe et al., 2009). Cellular responses elicited by exposure to T-oligo include the up-regulation of a DNA-damage-like response characterized by phosphorylation and activation of the DNA damage response proteins γ-H2A.X, ATM, and chk2. (Eller et al., 2006; Rankin et al., 2012) In cancer cells containing wild-type p53, this signaling cascade results in p53 stabilization and the transcriptional upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21waf1/cip1, followed by cell death (Li et al., 2004). Interestingly, certain cancer cell lines with mutated p53 have also demonstrated significant cytotoxic responses following exposure to T-oligo (Longe et al., 2009; Rankin et al., 2012), although the underlying molecular mechanism in this case is not yet elucidated. The prevailing hypothesis regarding T-oligo mechanism of action suggests the oligo interferes with functional telomeric structure (Eller et al., 2003), normally characterized by sequestration of 3′ single stranded telomeric DNA from the nuclear environment, which if exposed, serves as a physiological indicator of genomic stress and/or instability (Griffith et al., 1999; Karlseder et al., 1999). Varying T-oligo length and sequence has demonstrated a direct relationship between the percentage of guanine nitrogenous bases and effectiveness in inducing cytostatic and/or cytotoxic responses in cancer cells (Ohashi et al., 2007). In this report, we present data demonstrating the enhanced effectiveness of a deoxyguanosine-enriched sequence of T-oligo, termed (GGTT)4, which elicits robust cytotoxic effects in prostate cancer cells at lower concentrations than the most recent T-oligo sequence (5′ pGGT TAG GTG TAG GTT T 3′) studied to date.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

DU145, LNCaP, and PC-3 prostate cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. LN-4 is a subline of LNCaP that is no longer androgen dependent or adrogen-responsive. The pZ-HPV-7 prostate epithelium cell line, transformed by the human papillomavirus 18 (HPV-18), was obtained from Dr. Tai C. Chen, Boston University School of Medicine. DU145, PC-3, and LN-4 cells were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum purchased from Hyclone; Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) from Mediatech; 2 mM l-Glutamine from Gibco; 200 U/mL penicillin; 200 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). The LNCaP cell line was maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone); RPMI1640 medium (Gibco); 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco); 200 U penicillin/mL; 200 μg streptomycin/mL (Gibco). pZ-HPV-7 cells were maintained in MCDB-153 medium supplemented with 0.05 mg/mL l-histidine, 0.099 mg/mL l-isoleucine, 0.014 mg/mL l-methionine, 0.010 mg/mL l-tryptophan, 0.014 mg/mL l-tyrosine, 0.015 mg/mL l-phenylalanine, 5 μg/mL bovine insulin, and 50 ng/mL prostaglandin E1 all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Additional supplements were 30 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, 25 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 U/mL penicillin, and 200 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). All cell lines were propagated at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide (CO2).

Reagents

(GGTT)4 oligonucleotide 16-mer; 5′ GGT TGG TTG GTT GGT T 3′; telomere-specific oligonucleotide (T-oligo) 16-mer; 5′ pGGT TAG GTG TAG GTT T 3′; control oligonucleotide (C-oligo) 16-mer; and 5′ pAAA CCT ACA CCT AAC C 3′ sequences were provided by Dr. Mark S. Eller, Boston University School of Medicine. All oligonucleotides were synthesized by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) purification and purchased from Midland Certified Reagents. Propidium iodide, RNAse A, and trypan blue were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor SP600125 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences.

Cell enumeration assay

Cells were seeded in 60-mm tissue culture dishes. Cells were exposed to either T-oligo, (GGTT)4, C-oligo, or diluent for indicated time points, trypsinized, washed, and enumerated via trypan blue exclusion using disposable hemocytometers from Fisher Scientific.

Cell cycle analysis

Fixing and propidium iodide staining for flow cytometric analysis was performed as described previously (Vaziri et al., 1995). Linear and logarithmic cell cycle profiles were generated from 15,000 events/sample on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter using CellQuest Pro software, both purchased from Becton Dickinson.

Annexin 5–fluorescein assay

Cells were exposed to T-oligo, (GGTT)4, C-oligo, or diluent for indicated time points, trypsinized, fixed, and stained with Annexin 5–fluorescein (FITC) using the Annexin 5–FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I purchased from BD Biosciences according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Immunoblot analyses

Cells were lysed in 1% nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP)-40 lysis buffer containing sodium orthovanadate, okadaic acid, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sarkar et al., 2011). For specific protein detection, equal amounts of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with either 5% bovine serum albumin in tris-buffered saline/tween (TBST) for phospho-protein detection, or 3% nonfat milk also dissolved in TBST. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described (Sarkar et al., 2011). Antibodies against phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK)1 (T183) or p-JNK2 (Y185) were purchased from AbCam, against total JNK 1, 2, or 3 or total cJun from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and against p-cJun (S63) from Cell Signaling Technology.

Results

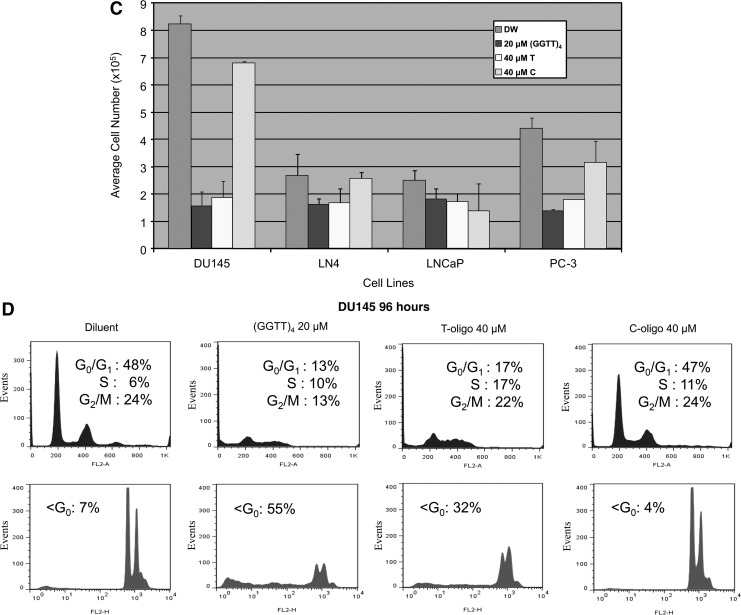

A 16-mer, single-stranded oligonucleotide with sequence homology to human telomeric DNA (T-oligo) was tested for its activity on three human prostate cancer cell lines: DU145, PC-3, and LNCaP. Each line was derived from advanced human prostate cancers, with only the LNCaP line remaining responsive to androgens or androgen antagonists (Dai et al., 2007). Exposure of the DU145 and PC-3 cell lines to T-oligo at cytotoxic concentrations resulted in accumulation of cells bearing DNA levels characteristic of S-phase by 48 hours (Fig. 1A, B). These findings are consistent with the S-phase arrest described previously in human fibroblasts exposed to an 11-mer of similar sequence (Eller et al., 2002). By 96 hours of exposure, normal cell cycle profiles were disrupted. Cell cycle profiles of these cells following exposure to identical concentrations of C-oligo were not altered when compared to diluent controls. In contrast, the cell cycle profile of the LNCaP cell line was not affected by exposure to either the T-oligo or C-oligo when compared to diluent control (Fig. 1C). Previous studies have cited the lack of toxicity of 11-mer T-oligo on nontransformed cells (Aoki et al., 2007; Yaar et al., 2007; Longe et al., 2009). To explore the effects of the 16-mer T-oligo on nontransformed human prostate epithelial cells, the immortalized line pZ-HPV-7 was studied. Exposure to T-oligo or C-oligo control for 48 or 96 hours had no effect on cell cycle profiles of the prostate epithelial cells (Fig. 2). Quantitation of the cell population fraction with subdiploid DNA content (apoptotic fraction) at 96 hours did not differ among the cultures exposed to either of the oligonucleotides or the diluent. Viable cell enumeration at 48 and 96 hours showed no effect by either oligo on cell number at either time point (data not shown). To determine whether induction of apoptosis by the T-oligo may have contributed to the reductions in cell number of the DU145 cells, an Annexin 5 assay was performed to quantify apoptotic cells. DU145 prostate cancer cells exposed for 96 hours to T-oligo displayed a population in early apoptosis [Annexin 5 positive (+), propidium iodide [PI] negative (−)] and late apoptosis (Annexin 5+, PI+). In parallel analyses, exposure to the T-oligo altered cell cycle profiles in the DU145 cells and increased the hypodiploid cell fraction, as expected (Fig. 3). Enumeration of viable cells demonstrated a significant (73%) decrease in viable cells at this timepoint compared to cultures exposed to C-oligo or diluent controls (P<0.01, data not shown). The duration of exposure required to generate cytotoxic effects on prostate cancer cell lines was explored using washout studies. DU145 cells were exposed for 120 hours to either 40 μM T-oligo or 40 μM C-oligo, or diluent. A parallel cohort was exposed for 72 hours to identical conditions, followed by replacing the media with oligo-free growth media, and continuation of culture for an additional 48 hours. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for cell cycle profiles and apoptosis, and viable cells were enumerated. In the cultures continuously exposed to T-oligo, suppression of cell number was evident by 48 hours, and a decrease of 82% in viable cell count was observed at 96 hours, compared with treatment with control oligonucleotide (Fig. 4A, top panel). When the cells which remained viable at 72 hours of exposure to T-oligo were cultured in the absence of T-oligo (in either diluent or C-oligo), regrowth was observed 24 and 48 hours thereafter, although viable cell numbers remained significantly less than C-oligo control at both time points after washout (Fig. 4A: bottom panel). Parallel analyses of DNA profiles in these studies demonstrated a decrease in the hypodiploid cell population fraction (from 37% to 18%) and the establishment of a population of cells with normal DNA profiles at 24 hours following washout, compared with those cultures exposed continuously to T-oligo (Fig. 4B). Re-exposure of these viable cells, after washout, to T-oligo resulted in cytotoxicity comparable to exposure of naïve cell cultures (data not shown). Studies to optimize the sequence of T-oligo for induction of cytotoxic responses suggested that increases in the deoxyguanosine content resulted in increased anti-tumor activity. An optimized 16-mer, designated (GGTT)4, was tested against the human prostate cancer cell lines in comparison with T-oligo, C-oligo, or diluent. Dose-ranging studies in multiple tumor cell lines demonstrated that a concentration of 20 μM (GGTT)4 produced maximal cytotoxicity (data not shown). Exposure to (GGTT)4 resulted in significant growth inhibition of DU145 prostate cancer cells (Fig. 5A), at least equivalent to the effects of T-oligo at twice the concentration, at 72 and 96 hours, compared to diluent or C-oligo control cultures. As with T-oligo, exposure to (GGTT)4 for as little as 24 hours, followed by washout of the oligo, was sufficient to produce significant inhibition of cell proliferation at later time points (Fig. 5B). (GGTT)4 at 20 μM was as effective as T-oligo at 40 μM in inhibiting the growth of other human prostate cancer cell lines, including PC-3 and LN4. LNCaP cells remained relatively insensitive to (GGTT)4, as was observed with the T-oligo studies (above) (Fig. 5C). Examination of cellular DNA content by flow cytometry demonstrated disruption of the normal cell cycle profiles in DU145 cells exposed to (GGTT)4 or T-oligo, with accumulation of a major subdiploid population at 96 h, indicative of apoptosis (Fig. 5D). Other reports have suggested the anti-proliferative activity of telomeric G-tail oligodeoxynucleotides (TG-ODNs) and nontelomeric G-quadruplex ODNs (GQ-ODN) against tumor cells is dependent upon their G-quadruplex conformation which elicited activation of the JNK pathway, as evidenced by elevated phosphorylation of the cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and cJun (Qi et al., 2006). We found that (GGTT)4 induced activation of JNK in prostate cancer cells at concentrations which induced cytotoxicity, as was observed with T-oligo with less potency (Fig. 6A). SP600125, a cell-permeable, selective, and reversible inhibitor of JNK (Bennett et al., 2001), when exposed to DU145 cells at concentrations sufficient to inhibit cJun phosphorylation, (Fig. 6B), partially rescued the anti-proliferative effects of both T-oligo (data not shown) and (GGTT)4 (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 1.

Effects of T-oligo on cell cycle profiles in human prostate cancer cells. DU145 (A), PC-3 (B), and LNCaP (C) prostate cancer cell lines were exposed to T-oligo or C-oligo (each at 40 μM) or diluent for 48 or 96 hours. DNA content was analyzed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry.

FIG. 2.

Effects of T-oligo on cell cycle profiles of human prostate epithelial cells. The pZ-HPV-7 immortalized human prostate epithelial cell line was exposed to either diluent, T-oligo, or C-oligo (each at 40 μM) for 48 or 96 hours. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for DNA content profiles and for hypodiploid cell populations (bottom panels). In this panel, the population identified as M1 represents the hypodiploid fraction (<2N DNA content).

FIG. 3.

T-oligo-induced apoptosis of human prostate cancer cell lines. DU145 prostate cancer cells were treated for 96 hours with either diluent or T-oligo (40 μM). Cells were harvested and stained with annexin 5-fluorescein (FITC) and propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry for apoptosis and DNA content.

FIG. 4.

Duration of exposure to T‐oligo required to generate cytotoxic effects. (A) Top panel: DU145 cells were continuously exposed to T‐oligo (T), C‐oligo (C), or diluent (DW), and harvested at the indicated time points and viable cells were enumerated. Bottom panel: DU145 cells were exposed to T‐oligo (T), C‐oligo (C), or diluent (DW) for 72 hours, then medium was washed out and replaced with growth medium free of oligonucleotide and culture was continued. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points, including 24 and 48 hours after washout and viable cells were enumerated. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM); p values were determined using Student's t‐test (*p<0.05 for 24‐hour timepoint; †p<0.05 for 48‐hour timepoint). (B) Cell cycle profiles following washout of oligonucleotides. DU145 prostate cancer cells were exposed continuously for 96 hours to either diluent, T‐oligo, or C‐oligo (each at 40 μM) (continuous treatment). In parallel, a different cohort of DU145 were exposed in an identical fashion for 72 hours, followed by washout of the oligonucleotides and continuation of culture for 24 hours (washout post 24‐hour treatment). Cells were harvested, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of effects of T‐oligo and (GGTT)4 on prostate cancer cell proliferation and cell cycle profiles. (A) DU145 cells were exposed to either diluent (DW), (GGTT)4 at 20 μM, T‐oligo at 40 μM (T), or C‐oligo at 40 μM (C). Viable cells were enumerated after 72 and 96 hours of exposure. Error bars represent SEM; p values were determined by Student's t‐test (*p<0.005). (B) DU145 cells were exposed to either diluent (DW), (GGTT)4 at 20 μM, or T‐oligo at 20 μM (T) for 24 hours. The medium on all cultures was then changed and replaced with fresh growth medium. Viable cells were enumerated 96 hours later. Error bars represent SEM. Cell numbers in the cultures exposed to T‐oligo compared to those exposed to (GGTT)4 were significantly different at day 5 (*p<0.02; determined by Student's t‐test). (C) DU145, LN4, LNCaP, or PC‐3 cells were exposed to either diluent (DW), (GGTT)4 at 20 μM, T‐oligo at 40 μM (T), or C‐oligo at 40 μM (C). Viable cells were enumerated 96 hours later. Error bars represent SEM. Values for the (GGTT)4‐ or T‐oligo‐treated cultures compared to the vehicle‐ or C‐oligo‐treated cultures were significant for the DU145, LN4, and PC3 cell lines ( p<0.01; determined by Student's t‐test). (D) Cells were exposed to either diluent, (GGTT)4 at 20 μM, T‐oligo at 40 μM, or C‐oligo at 40 μM. Cells were collected at 72 and 96 hours, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

FIG. 6.

Effect of (GGTT)4 exposure on cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling. (A) Top panel: DU145 cells were exposed to either diluent, (GGTT)4, or T-oligo at the concentrations indicated for 12 hours, then harvested for isolation of proteins. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with antibodies against total JNK and phospho-JNK (p-JNK). Bottom panel: normalized quantification of p-JNK band intensity from top panel of Figure 6A. (B) Top panel: DU145 cells were exposed to either (GGTT)4 at 20 μM or to JNK inhibitor SP600125 at 10 μM, or both simultaneously for 12 hours, then harvested for isolation of proteins. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with antibodies against p-cJun or total cJun. Bottom panel: normalized quantification of p-JNK band intensity from top panel of Fig. 6B. (C) DU145 cells were cultured in the presence of diluent (control), (GGTT)4 at 20 μM, or JNK inhibitor SP600125 at 10 μM, or to both (GGTT)4 and SP600125 simultaneously [(GGTT)4+SP]. Viable cells were enumerated 96 hours later. Error bars represent SEM. Differences between cultures exposed to (GGTT)4 versus (GGTT)4 plus SP600125 were significant (*p<0.01; determined by Student's t-test).

Discussion

Prostate cancer is estimated to account for a quarter of all cancers diagnosed in 2011 (Siegel et al., 2011). Although there have been inroads to successfully treating localized disease with either radiotherapy or prostatectomy, patients presenting with advanced disease have little therapeutic recourse (Violette et al., 2012), thus underscoring the need for novel treatment modalities. T-oligo, single-stranded deoxyguanosine-rich oligonucleotides, have produced cytostatic and/or cytotoxic effects in diverse cancer cell lines of various species and tissues, including breast cancer (Yaar et al., 2007), melanoma (Puri et al., 2004), prostate (Gnanasekar et al., 2009), glioma (Aoki et al., 2007), B- and T-cell lymphoma (Longe et al., 2009), osteosarcoma (Eller et al., 2003), pancreatic (Rankin et al., 2012), and ovarian cancers (Sarkar et al., 2011). In this report, we demonstrate the cytostatic and cytotoxic effects on prostate cancer cell lines resulting from exposure to T-oligo. With 48 hours of exposure to T-oligo, but not at earlier time points, DU145 and PC-3 prostate cancer cells demonstrated disruption of cell cycle profiles, characterized by an increase in the proportion of cells with S-phase levels of DNA, an observation consistent with previous reports on T-oligo effects in cancer cells. Interestingly, LNCaP prostate cancer cells failed to demonstrate equitable cytostatic or cytotoxic effects compared with DU145 or PC3 cells. This observation is intriguing as LNCaP cells are androgen sensitive, whereas DU145 or PC3 are not. Further studies are being conducted to assess whether androgen sensitivity in prostate cancer cells can serve as a predictive biomarker for response to T-oligo exposure.

Significantly, these oligonucleotides do not produce cytotoxicity in normal cell types in vitro, including mammary epithelial cells (Puri et al., 2004), astrocytes (Aoki et al., 2007), and B-cell lymphocytes (Longe et al., 2009). We show here that they do not generate cytotoxicity in pZ-HPV-7 cells, a human prostate epithelial cell line. Even within 96 hours of exposure to cytotoxic levels of T-oligo, no evidence of apoptosis or cell cycle disruption was observed. In vitro studies have not shown toxicity in animal models, suggesting the tumor specificity and potential of these oligonucleotides as targeted therapeutic agents (Yaar et al., 2007; Longe et al., 2009).

Previous reports have demonstrated the rapid nuclear accumulation of T-oligo within 30 minutes of exposure to melanoma or breast cancer cells (Ohashi et al., 2007), suggesting a very rapid cellular uptake, although exposure times necessary for induction of apoptosis were not determined in any cell type. To assess the effect of modulating duration of T-oligo exposure on prostate cancer cells, washout studies were performed in this report. Notably, cells exposed continuously to T-oligo for 72 hours demonstrated greater cytotoxic effect compared with cells exposed for only 48 hours followed by exposure to T-oligo-free complete media for an additional 24 hours. Additionally, reexposure of tumor cells which escaped apoptosis during initial exposure to T-oligo again produced cytotoxic effects, thus mitigating concerns over potential resistance in heterogeneous cancer cell populations.

Recently, studies have sought to develop and understand correlations between T-oligo sequence and observed cytostatic and/or cytotoxic effects upon exposure to cancer cells. For instance, T-oligos of identical length, but with higher relative deoxyguanosine content, have demonstrated more robust cytotoxic effects in cancer cells compared with those with low deoxyguanosine (Ohashi et al., 2007). This phenomena was also observed in prostate cancer cells when T-oligos bearing differential deoxyguanosine content were compared directly in this report. Specifically, a T-oligo bearing four tandem repeats of GGTT, identified in this report as (GGTT)4, demonstrated equitable cytotoxic effects at half the concentration observed from exposure of cells to a sequence with identical length, but containing a sequence largely homologous with human telomeric DNA. This striking observation questions the currently accepted model for T-oligo function; namely, that T-oligo elicits its cytotoxic effects by interfering in an unknown manner with telomeric structure, or possibly serving as a destabilized telomere mimic (Li et al., 2003; Li et al., 2004; Eller et al., 2006). It is quite possible, though untested to date, that the deoxyguanosine-rich T-oligo may share mechanistic similarities to other cytotoxic and G-rich oligonucleotides developed independently of T-oligo (Saijo et al., 1997). Recent reports have posited that the cytostatic activity of telomeric TG-ODNs and nontelomeric GQ-ODNs against tumor cells correlates with their ability to form higher order nucleic acid structure; i.e. G-quadruplexes which activate signaling through the JNK pathway, as evidenced by elevated phosphorylation of JNK and cJun. (Qi et al., 2006) Similarly, agents that coordinate and stabilize DNA G-quadruplexes activated JNK, suggesting a common signaling mechanism (Mikami-Terao et al., 2008). TG- and GQ-ODN-induced apoptosis was inhibited by the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Qi et al., 2006). We show here that (GGTT)4, and to a lesser extent T-oligo, at concentrations which retard cell proliferation, induce activation of JNK as indicated by its activating phosphorylation. JNK inhibition by a selective agent provided substantial protection from the cytostatic actions of (GGTT)4, suggesting that JNK mediates all or a substantial part of this cytostasis. These findings are consistent with (GGTT)4 acting through G-quadruplex formation through interaction with telomeric sequences.

Together the data in this report support T-oligo as a potential therapeutic for advanced androgen-independent prostate cancers. Recent reports have supported T-oligo as a potential adjuvant to the current standard of care in a non-Hodgkin's-like lymphoma mouse model (Longe et al., 2009). As such, current efforts in our lab at examining T-oligo as a therapeutic oligonucleotide in vivo will address questions regarding its utility as a single agent or adjuvant to the current standard of care in reducing or eliminating tumor burden in prostate xenograft mouse models.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work has been provided by United States Department of Defense, contract grant numbers W81XWH-07-1-0577 and W81XWH-06-1-0408; The National Cancer Institute, contract grant number CA133654; and Karin Grunebaum Cancer Research Foundation (DVF).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- AOKI H. IWADO E. ELLER M.S. KONDO Y. FUJIWARA K. LI G.Z. HESS K.R. SIWAK D.R. SAWAYA R. MILLS G.B., et al. Telomere 3′ overhang-specific DNA oligonucleotides induce autophagy in malignant glioma cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:2918–2930. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6941com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENNETT B. SASAKI D.T. MURRAY B.W. O'LEARY E.C. SAKATA S.T. XU W. LEISTEN J.C. MOTIWALA A. PIERCE S. SATOH Y., et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI Y. NGO D. FORMAN L.W. QIN D.C. JACOB J. FALLER D.V. Sirtuin 1 is required for antagonist-induced transcriptional repression of androgen-responsive genes by the androgen receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;21:1807–1821. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLER M.S. PURI N. HADSHIEW I.M. VENNA S.S. GILCHREST B.A. Induction of apoptosis by telomere 3′ overhang specific DNA. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;276:185–193. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLER M.S. LI G.Z. FIROOZABADI R. PURI N. GILCHREST B.A. Induction of a p95/Nbs-1- mediated S phase checkpoint by telomere 3′ overhang specific DNA. FASEB J. 2003;2:152–162. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0197com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLER M.S. LIAO X. LIU S. HANNA K. BÄCKVALL H. OPRESKO P.L. BOHR V.A. GILCHREST B.A. A role for WRN in telomere-based DNA damage responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:15073–15078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607332103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GNANASEKAR M. THIRUGNANAM S. ZHENG G. CHEN A. RAMASWAMY K. T-oligo induces apoptosis in advanced prostate cancer cells. Oligonucleotides. 2009;3:287–292. doi: 10.1089/oli.2009.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA J.A. RINI B.I. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: many treatments, many options, many challenges ahead. Cancer. 2011;118:2583–2593. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEORGE D. MOUL J.W. Emerging treatment options for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 2012;72:338–349. doi: 10.1002/pros.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITH J.D. COMEAU L. ROSENFELD S. STANSEL R.M. BIANCHI A. MOSS H. DE LANGE T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARLSEDER J. BROCCOLI D. DAI Y. HARDY S. DE LANGE T. p53- and ATM-dependent apoptosis induced by telomeres lacking TRF2. Science. 1999;283:1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI G.Z. ELLER M.S. FIROOZABADI R. GILCHREST B.A. Evidence that exposure of the telomere 3′ overhang sequence induces senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:527–531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235444100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI G.Z. ELLER M.S. HANNA K. GILCHREST B.A. Signaling pathway requirements for induction of senescence by telomere homolog oligonucleotides. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;301:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LONGE H.O. ROMESSER P.B. FALLER D.V. ELLER M.S. GILCHREST B.A. SINHA A. DENIS G.V. Telomere DNA-based adjunctive therapy is effective for lymphoid malignancy. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2007;2007:1216. [Google Scholar]

- LONGE H.O. ROMESSER P.B. RANKIN A.M. FALLER D.V. ELLER M.S. GILCHREST B.A. DENIS G.V. Telomere homolog oligonucleotides induce apoptosis in malignant but not in normal lymphoid cells: mechanism and therapeutic potential. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;2:473–482. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIKAMI-TERAO Y. AKIYAMA M. YUZA Y. YANAGISAWA T. YAMADA O. YAMADA H. Antitumor activity of G-quadruplex-interactive agent TMPyP4 in K562 leukemic cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;261:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHASHI N. YAAR M. ELLER M.S. TRUZZI F. GILCHREST B.A. Features that determine telomere homolog oligonucleotide-induced therapeutic DNA damage-like responses in cancer cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2007;210:582–595. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETRYLAK D.P. TANGEN C.M. HUSSAIN M.H.A. LARA P.N. JONES J.A. TAPLIN M.E. BURCH P.A. BERRY D. MOINPOUR C. KOHLI M., et al. Docetaxel and stramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PURI N. ELLER M.S. BYERS H.R. DYKSTRA S. KUBERA J. GILCHREST B.A. Telomere-based DNA damage responses: a new approach to melanoma. FASEB J. 2004;18:1373–1381. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1774com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QI H. LIN C.P. FU X. WOOD L.M. LIU A.A. TSAI Y.C. CHEN Y. BARBIERI C.M. PILCH D.S. LIU L.F. G-quadruplexes induce apoptosis in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11808–11816. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANKIN A.M. SARKAR S. FALLER D.V. Mechanism of T-oligo-induced cell cycle arrest in Mia-Paca pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2586–2594. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAIJO Y. UCHIYAMA B. ABE T. SATOH K. NUKIWA T. Contiguous four-guanosine sequence in c-myc antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides inhibits cell growth on human lung cancer cells: possible involvement of cell adhesion inhibition. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1997;88:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARKAR S. ABUJAMRA A.L. LOEW J.E. FORMAN L.W. PERRINE S.P. FALLER D.V. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reverse CpG methylation by regulating DNMT1 through ERK signaling. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2723–2732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEGEL R. WARD E. BRAWLEY O. JEMAL A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer. J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANNOCK I.F. DE WIT R. BERRY W.R. HORTI J. PLUZANSKA A. CHI K.N. OUDARD S. THEODORE C. JAMES N.D. TURESSON I., et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAZIRI C. FALLER D.V. Repression of platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor expression by mitogenic growth factors and transforming oncogenes in murine 3T3 fibroblasts. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:1244–1253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIOLETTE P.D. SAAD F. Chemoprevention of prostate cancer: myths and realities. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2012;25:111–119. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAAR M. ELLER M.S. PANOVA I. KUBERA J. WEE L.H. COWAN K.H. GILCHREST B.A. Telomeric DNA induces differentiation, apoptosis, and senescence of human breast carcinoma cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R13. doi: 10.1186/bcr1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]