Abstract

The amplitudes of many circadian rhythms, at the behavioral, physiological, cellular, and biochemical levels, decrease with advanced age. Previous studies suggest that the amplitude of the central circadian pacemaker is decreased in old animals. Recently, it has been reported that expression of several circadian clock genes, including Clock, is lower in the master circadian pacemaker of old rodents. To test the hypothesis that decreased activity of a circadian clock gene renders animals more susceptible to the effects of aging, we analyzed the circadian rhythm of locomotor activity in young and old wild-type and heterozygous Clock mutant mice. We found that the effects of age and the Clock mutation were additive. These results indicate that age-related changes in circadian rhythmicity occur equally in wild-type and heterozygous Clock mutants, suggesting that the Clock mutation does not render mice more susceptible to the effects of age on the circadian pacemaker.

Keywords: Aging, Circadian rhythm, Clock, Clock mutation

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with changes in the mammalian circadian timing system. These changes include decreases in the amplitude of many overt rhythms, including the rhythms of locomotor activity, drinking, body temperature, and the sleep–wake cycle [19,24,28,29,34], as well as corresponding decreases in the amplitudes of at least two rhythms of suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN, site of the master mammalian circadian pacemaker) physiology: the rhythms of neural firing rate and of glucose uptake [25,31,35]. Additionally, species-specific changes in the free-running period in constant darkness (τ) are often observed [15,21,27,28] Aging does not alter the size of the SCN or the number of neurons it contains [14,36], suggesting that the effects of age are due to changes in the pacemaking capabilities of the neurons or the connections between them.

Current models of the mammalian circadian clock suggest that individual neurons are capable of generating circa 24-h rhythms [33]. These rhythms are produced by interlocking molecular feedback loops of transcription, translation, and repression of transcription [22]. Recently, we [11] and others [1] reported that aging is correlated with decreased expression of several of the genes that make up these feedback loops, including both Clock and its binding partner, Bmal1. These results led us to hypothesize that animals which carry a mutation in a clock gene clock might be more susceptible to the effects of age on the circadian rhythms.

The Clock mutant mouse presents a model to test this hypothesis, as both old rodents and Clock mutant mice exhibit dampened circadian rhythms at the behavioral [20,30] and electrophysiological levels [7,17,31], as well as altered expression of circadian clock genes. Clock mutant mice carry a point mutation in the Clock sequence, which leads to the skipping of exon 19 in the mature mRNA, thereby producing a shorter protein [10]. The mutant form of the protein is able to dimerize with BMAL1, its binding partner, but cannot activate transcription of E-box-containing sequences. This leads to decreased accumulation of downstream protein products (including, but not limited to, the PER homologs) within the cell [8]. At the behavioral level, heterozygous Clock mutant mice have a circadian period approximately 25 h; homozygotes show 28-h rhythmicity for several cycles, followed by arrhythmicity in the circadian range [30].

Given the important role of Clock in generating circadian rhythms in young mice [30], and the fact that old rodents show decreased expression of several circadian genes, we hypothesized that animals with a defective circadian clock would be more susceptible to the effects of age on the circadian timing system. In the present set of experiments, we examined the circadian rhythm of locomotor activity in wild-type and heterozygous Clock mutant mice at 3 and 18 months of age. We found that the effects of age on the circadian timing system are essentially independent of Clock genotype. These results suggest that the age-related changes in circadian rhythms cannot be explained by changes in Clock activity alone.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

All animals were bred and born at the Center for Experimental Animal Resources at Northwestern University. Wild-type (C57BL/6J) and heterozygous Clock mutant mice (on a coisogenic C57BL/6J background [30]) were used. Animals were designated as either young (approximately 3 months old at the start of the experiment) or old (at least 18 months old at the start of the experiment). Some of the old animals had previously been exposed to varying light–dark (LD) cycles and running wheels when they were young.

2.2. Procedure

Animals were individually housed in cages equipped with a running wheel; a microcomputer running Chronobiology Kit software (Stanford Software Systems, Stanford, CA) recorded each revolution of the running wheel. The cages were kept in light-tight boxes equipped with a 40 W fluorescent lamp. Food and water were available ad libitum throughout the experiment. Animals were maintained in a 12 h/12 h LD cycle for at least 3 weeks. They were transferred to constant darkness (DD) by extension of the dark phase. Three weeks later, they were given a 6-h light pulse (40 W fluorescent lamp, 300–400 lx) beginning at circadian time CT 17; young Clock heterozygotes show significantly larger phase shifts to such light pulses [13]. They were returned to DD and after 10 days were sacrificed at CT 6. Brains were rapidly extracted, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C until in situ hybridization.

2.3. Probe template preparation

Total RNA was extracted from mouse brains with Trizol (Life Technologies, Bethesda, MD) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Approximately 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed (RT) with MMLV-RT (Promega, Madison, WI, 200 U final concentration) in the presence of dNTP (Promega, 500 μ/M), random hexamer primers (Promega, 2.5 ng/μl), RNAse inhibitor (Promega, 20 U), and RT reaction buffer (Promega, 1X). The RNA and primers were heated to 70 °C for 10 min and quenched on ice for 2 min. The remaining reaction components were added, incubated 10 min at room temperature, then for 60 min at 37 °C, and heat-inactivated for 5 min at 70 °C. An aliquot (1 μl) of this reaction product served as the template for PCR reactions. The following primer pairs, purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), were used to PCR-amplify cDNAs with a T7 RNA polymerase recognition site immediately 5′ of the antisense sequence: mPer1:5′-CCG GAA TTC AGC TCT GCT GGA GAC CAC TGA-3′ and 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GAG TGT ATT CGG ATG TGA TAT GCT CC-3′; mPer2:5′-ACG AGA ACT GCT CCA CGG-3′ and 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GAA CAG CCA CAG CAA ACA TAT CC-3′. The amplification conditions were: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final incubation at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR was carried out with AmpliTaq (Perkin-Elmer) in the presence of primers (250 nM each), dNTP (200 μM), and PCR buffer (1X). PCR products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels and the bands of the expected size were excised and gel-purified with QiaEX II (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

2.4. In situ hybridization

The brains were sectioned on a cryostat at 20 μm through the SCN. Alternate sections were collected on separate slides for hybridization with either mPer1 or mPer2 antisense riboprobes. Sections were thaw-mounted onto gelatin coated slides and frozen at 80 °C until ready for hybridization. All reagents were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) except as indicated. Slides were thawed under cool air, fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). They were treated with 2X SSC for 5 min, dipped in DEPC-treated water, dipped in 0.1 M triethanolamine (TEA, pH 8.0), and acetylated for 10 min in 0.25% acetic anhydride in TEA. They were dipped briefly in 2X SSC, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and stored under vacuum until completely dry. 33P-labeled riboprobes were transcribed from PCR templates (see above) with Ambion’s MaxiScript kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). Probe was diluted in hybridization solution (50% formamide (v/v), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1X Denhardt’s solution, 10% dextran sulfate (w/v), 750 μg/ml yeast RNA (Sigma R7125)) to a final concentration of approximately 5 × 107 cpm/ml. Sections were hybridized overnight at 48 °C in a humid chamber. The next day, coverslips were removed, and the sections were soaked in 4X SSC for 10 min twice. They were treated with RNAse A (20 μg/ml in 2X SSC) for 30 min at 37 °C, washed in 2X SSC for 30 min at 37 °C, and stringently washed for 30 min in 0.1X SSC at 60 °C. The sections recovered for 10 min in 1X SSC, were dehydrated through an ethanol series, vacuum dried, and exposed to Kodak Bio-Max MR film.

2.5. Data analysis and statistics

All activity data were recorded in 1-min bins using The Chronobiology Kit (Stanford Software Systems, Stanford, CA). The free-running period was calculated with a chi-squared periodogram (Chronobiology Kit) over the last 10 days in DD before the light pulse. The relative power of the circadian component of the fast-Fourier transformation (FFT) of the same data was calculated by ClockLab (Actimetrics, Inc., Evanston, IL). Average total activity per day (Chronobiology Kit) and the number of bouts of activity per day [20] were also computed over the same interval. Phase shifts were calculated by eye-fitting lines through the onsets of activity before and after administration of the light pulse.

In situ hybridization autoradiograms were scanned into a Power Macintosh at 2700 dpi with a Sprint Scanner (Polaroid, Inc., Cambridge, MA). The intensity of the signal in the SCN was quantified with NIH Image 1.6.1 and was calibrated to 14C microscales (Amersham) included in each cassette. To allow for comparison of data from multiple in situ hybridization experiments, data from each animal was normalized to the mean signal intensity for young wild-type animals in that experiment.

The data were analyzed with ANOVAs (Statview, Abacus Systems, Berkeley, CA; NCSS 97, Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, Kaysville, UT). Phase shifts were transformed into degrees and compared with F tests modified for use on circular statistics, although this method allows for only one independent variable (i.e. one can measure the effect of either age or genotype but not age x genotype interactions) [4]. Effects were considered significant at P<0.05. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M.

3. Results

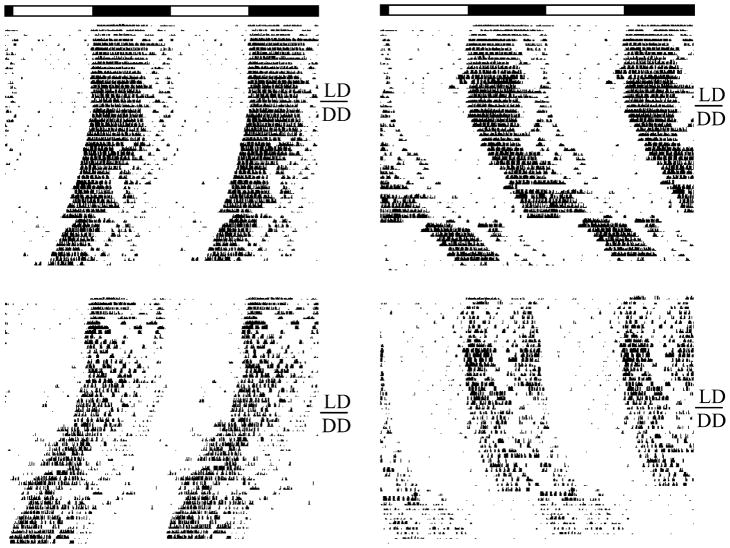

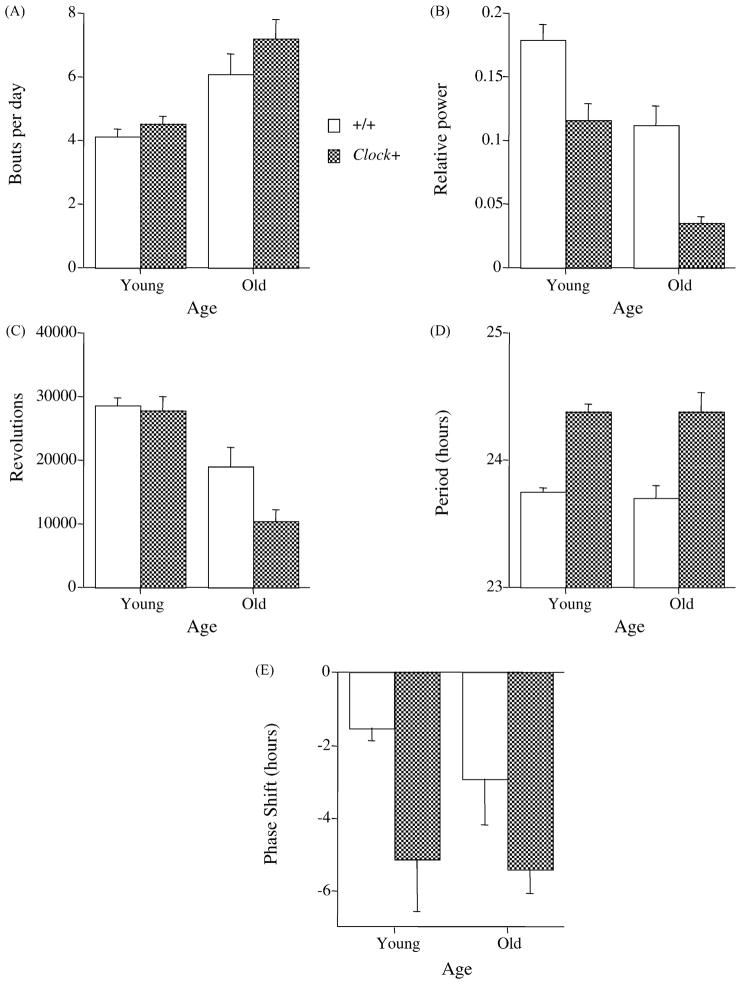

We found effects of age on several parameters of circadian rhythmicity. Representative actograms from young and old wild-type and Clock/+ mice are depicted in Fig. 1. The effect of the Clock mutation on τ is clearly visible, as is the effect of age on rhythm consolidation. Quantitative analysis of locomotor activity data revealed that old mice had significantly more bouts of locomotor activity per day than young mice (P<0.0001; see Fig. 2A). Aging also significantly reduced the relative power of the fast-Fourier transformation of the activity data in the circadian range (FFT; P< 0.0001; see Fig. 2B) and the number of wheel revolutions per day (P<0.0001; see Fig. 2C). There was no effect of age on either the free-running period in constant darkness (see Fig. 2D), or the magnitude of phase shifts induced by a 6-h light pulse at CT 17 (see Fig. 2E).

Figure 1.

Representative activity records from young (top) and old (bottom) wild-type and Clock mutant mice. Data from wild-type mice are on the left, and data from age-matched Clock/+ mice are on the right. The phase shifts near the bottom of each record are the result of a 6-h light pulse delivered at CT 17.

Figure 2.

Effects of age on various parameters of the circadian timing systems of wild-type and Clock mutant mice. Compared to young mice, old mice had significantly more bouts of activity per day (A), lower relative FFT power in the circadian range (B), fewer wheel revolutions per day (C). Age did not affect free-running period in constant darkness (D) or the magnitude of the light-induced phase shift (E). Clock mutant mice had significantly lower relative FFT power (B) and running wheel activity (C). The Clock mutation also led to a significantly longer free-running period (D) and larger phase shifts to a 6-h light pulse delivered at CT 17 (E). Open bars: wild-type mice. Dark bars: Clock heterozygotes.

Consistent with previously reported results [30], Clock mutant mice had significantly longer τ and lower relative FFT power in the circadian range than wild-type mice (P’s <0.0001; see Fig. 2D and B). Clock mutant mice also ran in their wheels significantly less than wild-type mice (P< 0.05; see Fig. 2C). There was a significant effect of genotype (P<0.001), but not age (P>0.50), on the magnitude of the phase shifts induced by a 6-h light pulse at CT 17 (see Fig. 2E). In an attempt to detect age x genotype interactions, the phase-shifting data were also subjected to a two-way ANOVA, which revealed that Clock mutant mice had larger phase shifts than +/+ mice, although there was no age x genotype interaction (P = 0.87). In fact, there were no significant age x genotype interaction effects for any of the circadian parameters measured.

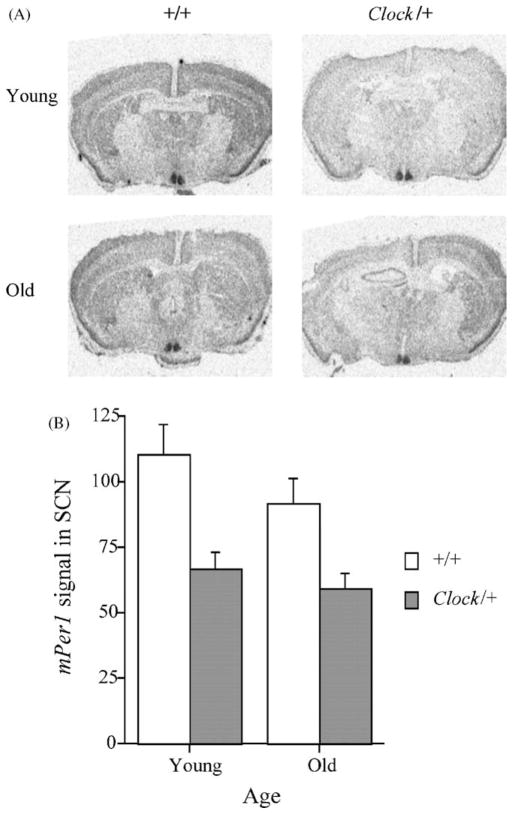

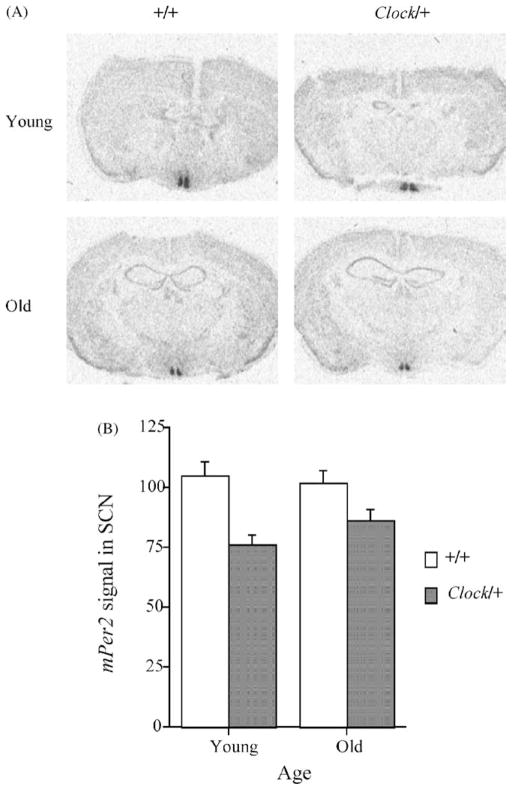

In situ hybridization experiments revealed that at CT 6, Clock mutant mice expressed less mPer1 (P<0.01; see Fig. 3) and mPer2 (P<0.05; see Fig. 4) mRNA in the SCN than wild-type mice. The expression of these two genes was not influenced by age, nor were there age x genotype interactions (P’s >0.22).

Figure 3.

The expression of mPer1 was significantly lower in the SCN of Clock mutant mice at CT 6. (A) Autoradiograms of hypothalami from representative young and old wild-type and Clock mutant mice. (B) mPer1 signal in the SCN of animals from each group. Age did not significantly affect mPer1 expression.

Figure 4.

The Clock mutation significantly decreased expression of mPer2 in the SCN at CT 6. (A) Autoradiograms of hypothalami from representative young and old wild-type and Clock mutant mice. (B) mPer2 signal in the SCN of animals from each group. There was no effect of age on the mPer2 expression.

4. Discussion

The results of these experiments suggest that the effects of aging and Clock genotype on the circadian timing system are additive, not interactive. That is, Clock mutant mice are as susceptible as wild-type mice to the effects of age on the circadian clock. While they clearly have altered circadian rhythms as young adult animals, and these disruptions are exacerbated by age, the age-related changes in the rhythms of mutant mice are similar to those of wild-type mice.

The present data confirm some of the previously reported effects of age on the mouse circadian clock. Valentinuzzi et al. [28] found that in wild-type C57BL/6J mice (the same strain as the +/+ mice used here), age increases the number of bouts of locomotor activity per day and decreases the total amount of wheel-running activity; we found the same effects of age on these parameters independent of Clock genotype (see Fig. 2A and C). We also found that the relative power of the FFT of activity data decreased in old age (see Fig. 2B). Together with the increase in the number of bouts of activity per day, this suggests that the amplitude of, coupling within, or output from the master circadian pacemaker is decreased by age, and is consistent with both in vitro and in vivo data collected from aging rodents [12,23–25,35]. Recently, Aujard et al. [2] reported that aging decreased the amplitude of the rhythm of firing rate in individual SCN neurons, suggesting that the effects of age on the circadian pacemaker are at the level of individual cells, although this does not necessarily preclude the possibility that coupling strength, either between individual pacemaking neurons or between the pacemaker and its outputs, is influenced by age.

It has previously been reported that τ lengthens in aging C57BL/6J mice [15,28], although we found no change in τ here (see Fig. 2D). Data from the literature on the age-related change in τ are ambiguous; at least one other study of the effects of aging on the circadian rhythms of C57BL/6J mice failed to find a change in τ [32]. Experiments on the effects of age on τ in other species are also conflicting: for example, there are several reports of a shortening of τ in old golden hamsters [16,18,21,23], although one recent report found no significant age-related change in τ in the same species [6]. Similarly, in humans, there are recent reports of both changes [9] and lack of changes [5] in τ with advancing age. The effect of age on τ appears to be subtle at best; when it has been found the magnitude of the change in τ is often on the order of 0.5 h or less.

Although we did not observe an age-related change in τ in either wild-type or Clock/+ mice, we did find evidence of decreased amplitude of the circadian pacemaker in old animals. Relative FFT power, which reflects how much of the variability in the activity rhythm is due to circa 24-h components, decreased as both wild-type and Clock mutant mice aged. Relative FFT power may be a better indicator of the state of the circadian pacemaker than τ, as it reflects rhythm amplitude. The age-related changes in τ are relatively subtle (see above), and the direction of the change, when it is observed, tends to be species-dependent (e.g. aging shortens τ in hamsters but lengthens it in mice). Given that age-related changes in τ have been found by some researchers and not others, we are reluctant to draw strong conclusions as to whether or not this is a hallmark of aging of the circadian timing system. Together the data from the present experiment suggest that a mutation that has pronounced effects on the circadian timing system of young adult animals (i.e. being heterozygous for the Clock mutation) does not have a major effect on the way the circadian rhythm of locomotor activity changes with age.

Aging did not alter the expression of either mPer1 or mPer2 in the SCN at CT 6. Given the importance, these genes have in the generation of circadian rhythms [3,26,38,39], one might expect that expression of either or both of these per homologs would be decreased in the SCN of old mice. While we found no support for this hypothesis, the data are consistent with those recently obtained from both hamsters and rats [1,11,37]. We recently reported that across the circadian cycle, there are no differences between young and old hamsters in the expression of either Per1 or Per2, although light induced less Per1 in the SCN of old hamsters [11]. Asai et al. [1] found similar results in rats, while Yamazaki et al. [37] found that advanced age does not dampen rhythmic expression of a Per1-driven luciferase in the SCN of rats. It appears that while induction of the per homologs by light is altered in old age, the daily rhythm of expression of these genes is similar in the SCN of young and old rodents.

We sought to determine if Clock plays a causal role in the severity of age-related changes in the circadian timing system. Evidence for such a role would be indicated by effects of age on Clock mutant mice that are different from those typically seen in wild-type mice. As we found that the effects of age were on the circadian timing system were similar in wild-type and mutant mice, we conclude that Clock is not the primary causative agent of the age-related changes in circadian rhythmicity. It is possible that the effects of age on the circadian timing system may be due to changes in the expression or activity of one or more of the other circadian clock genes. However, since the expression of Per homologs in the SCN is not altered by age [1,11], it is also possible that age-related changes in the expression of circadian rhythmicity are due to alterations in the efficacy of communication between the thousands of individual pacemakers that comprise the mammalian SCN, or to a decrease in the strength of coupling between the oscillating mechanism and the output signal. Old rodents show a lower peak firing rate of SCN neurons [25], which could lead to decreased synchrony amongst the various oscillators.

A limitation of this experiment was that Clock mutant mice were only compared to wild-type mice at two ages. Thus a difference in the rate of age-related changes in circadian rhythmicity without a change in their severity would not be detected by the method used here. It is possible that the Clock mutation makes mice susceptible to the effects of age on the circadian timing system at an earlier age. Differences of this sort could be revealed either by studying more groups of wild-type and Clock mutant mice at intermediate ages, or by repeatedly examining a cohort of animals at multiple ages through a longitudinal study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants R01-AG-18200 (to F.W.T.) and P01-AG-11412 (to F.W.T. and J.S.T.) from the National Institutes of Health. J.S.T. is an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Asai M, Yoshinobu Y, Kaneko S, Mori A, Nikaido T, Moriya T, et al. Circadian expression of Per gene mRNA expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, paraventricular nucleus, and pineal body of aged rats. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:1133–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aujard F, Herzog ED, Block GD. Circadian rhythms in firing rate of individual suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons from adult and middle-aged mice. Neuroscience. 2001;106:255–61. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae K, Jin X, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Differential functions of mPer1, mPer2, and mPer3 in the SCN circadian clock. Neuron. 2001;30:525–36. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batschelet E. Statistical methods for the analysis of problems in animal orientation and certain biological rhythms. Washington: American Institute of Biological Sciences; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, et al. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999;284:2177–81. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis FC, Viswanathan N. Stability of circadian timing with age in Syrian hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R960–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzog ED, Takahashi JS, Block GD. Clock controls circadian period in isolated suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:708–13. doi: 10.1038/3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin X, Shearman LP, Weaver DR, Zylka MJ, De Vries GJ, Reppert SM. A molecular mechanism regulating rhythmic output from the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Cell. 1999;96:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendall AR, Lewy AJ, Sack RL. Effects of aging on the intrinsic circadian period of totally blind humans. J Biol Rhythms. 2001;16:87– 95. doi: 10.1177/074873040101600110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Wilsbacher LD, Tanaka M, Antoch M, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian Clock gene. Cell. 1997;89:641–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolker DE, Fukuyama H, Huang DS, Takahashi JS, Horton TH, Turek FW. Aging alters circadian and light-induced expression of clock genes in golden hamsters. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18:159–69. doi: 10.1177/0748730403251802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolker DE, Turek FW. Circadian rhythms and sleep in aging rodents. In: Hof C, Mobbs P, editors. Functional neurobiology of aging. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low-Zeddies SS, Takahashi JS. Chimera analysis of the Clock mutation in mice shows that complex cellular integration determines circadian behavior. Cell. 2001;105:25–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madeira MD, Sousa N, Santer RM, Paula-Barbosa MM, Gundersen HJ. Age and sex do not affect the volume, cell numbers, or cell size of the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the rat: an unbiased stereological study. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:585–601. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayeda AR, Hofstetter JR, Possidente B. Aging lengthens TauDD in C57BL/6J, DBA/2J, and outbred SWR male mice (Mus musculus) Chronobiol Int. 1997;14:19–23. doi: 10.3109/07420529709040538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morin LP. Age but not pineal status, modulates circadian periodicity of golden hamsters. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8:189–97. doi: 10.1177/074873049300800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura W, Honma S, Shirakawa T, Honma K. Clock mutation lengthens the circadian period without damping rhythms in individual SCN neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:399–400. doi: 10.1038/nn843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penev PD, Turek FW, Wallen EP, Zee PC. Aging alters the serotonergic modulation of light-induced phase advances in golden hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R509–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penev PD, Zee PC, Turek FW. Monoamine depletion blocks triazolam-induced phase advances of the circadian clock in hamsters. Brain Res. 1994;637:255–61. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penev PD, Zee PC, Turek FW. Quantitative analysis of age-related fragmentation of hamster 24-h activity rhythms. Am J Physiol. 1998;273:R2132–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.6.R2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pittendrigh CS, Daan S. Circadian oscillations in rodents: a systematic increase of their frequency with age. Science. 1974;186:548–51. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4163.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–41. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg RS, Zee PC, Turek FW. Phase response curves to light in young and old hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R491–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.2.R491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satinoff E. Patterns of circadian body temperature rhythms in aged rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25:135–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satinoff E, Li H, Tcheng TK, Liu C, McArthur AJ, Medanic M, et al. Do the suprachiasmatic nuclei oscillate in old rats as they do in young ones? Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R1216–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.5.R1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shearman LP, Sriram S, Weaver DR, Maywood ES, Chaves I, Zheng B, et al. Interacting molecular loops in the mammalian circadian clock. Science. 2000;288:1013–9. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turek FW, Penev P, Zhang Y, Van Reeth O, Zee P. Effects of age on the circadian system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995;19:53–8. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valentinuzzi VS, Scarbrough K, Takahashi JS, Turek FW. Effects of aging on the circadian rhythm of wheel-running activity in C57BL/6 mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1957–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.6.R1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Gool WA, Mirmiran M. Age-related changes in the sleep pattern of male adult rats. Brain Res. 1983;279:394–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang A-M, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, McDonald JD, et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene Clock essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719– 25. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe A, Shibata S, Watanabe S. Circadian rhythm of spontaneous neuronal activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of old hamster in vitro. Brain Res. 1995;695:237–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00713-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wax TM. Runwheel activity patterns of mature-young and senscent mice: the effect of constant lighting conditions. J Gerontol. 1975;30:22–7. doi: 10.1093/geronj/30.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welsh DK, Logothetis DE, Meister M, Reppert SM. Individual neurons dissociated from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus express independently phased circadian firing rhythms. Neuron. 1995;14:697– 706. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whealin JM, Burwell RD, Gallagher M. The effects of aging on diurnal water intake and melatonin binding in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neurosci Lett. 1993;154:149–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90193-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise PM, Cohen IR, Weiland NG, London ED. Aging alters the circadian rhythm of glucose utilization in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5305–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods WH, Powell EW, Andrews A, Ford CW. Light and electron microscopic analysis of two divisions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the young and aged rat. Anat Rec. 1993;237:71–88. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092370108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki S, Straume M, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Block GD. Effects of aging on central and peripheral mammalian clocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10801–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152318499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng B, Albrecht U, Kaasik K, Sage M, Lu W, Vaishnav S, et al. Nonredundant roles of the mPer1 and mPer2 genes in the mammalian circadian clock. Cell. 2001;105:683–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng B, Larkin DW, Albrecht U, Sun ZS, Sage M, Eichele G, et al. The mPer2 gene encodes a functional component of the circadian clock. Nature. 1999;400:169–73. doi: 10.1038/22118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]