Abstract

Orofacial clefts (OFCs)—primarily cleft lip and cleft palate—are among the most common birth defects in all populations worldwide, and have notable population, ethnicity, and gender differences in birth prevalence. Interest in these birth defects goes back centuries, as does formal scientific interest; scientists often used OFCs as examples or evidence during paradigm shifts in human genetics, and have also used virtually every new method of human genetic analysis to deepen our understanding of OFC. This review traces the evolution of human genetic investigations of OFC, highlights the specific insights gained about OFC through the years, and culminates in a review of recent key OFC genetic findings resulting from the powerful tools of the genomics era. Notably, OFC represents a major success for genome-wide approaches, and the field is poised for further breakthroughs in the near future.

Keywords: genetics, paradigm, history, phenomics, phenotypes

1. INTRODUCTION

Orofacial clefts (OFCs)—primarily cleft lip (CL) and cleft palate (CP)—are among the most common birth defects in all populations worldwide (99, 100), and have notable population, ethnicity, and gender differences in birth prevalence. Interest in these birth defects goes back centuries (see sidebar Orofacial Clefts in Literature), as does formal scientific interest; scientists often used OFCs as examples or evidence during paradigm shifts in human genetics, and have also used virtually every new method of human genetic analysis to deepen our understanding of OFC.

In this review, I trace the evolution of etiologic investigations of OFC (with an emphasis on human genetics) and the role that OFCs played in that evolution. I also highlight the specific insights gained about OFCs at each stage of methods development/application. Valuable knowledge has been gained at each stage, culminating in a variety of key results in recent years that have brought us closer to an integrated understanding of the causes of these common birth defects.

OROFACIAL CLEFTS IN LITERATURE.

Because OFC is a common birth defect with a chance of survival even in presurgical eras, there are references to it in myths, legends, art, and literature worldwide. OFC has been used for comic effect; e.g., Camille, a major character in the 1907 play A Flea in Her Ear (42), has CP and repeatedly loses his silver obturator (an intraoral appliance, usually removable, to close the gap of a cleft palate and facilitate speaking and eating), resulting in many comic misunderstandings. OFC is also used as shorthand for either a saintly character [e.g., Hassan in The Kite Runner (59, pp. 3, 10)] or undesirable qualities, as in the works of Shakespeare. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream (122, act 5, scene 1, lines 2260–65), Oberon predicts all good things for the three couples (“hare lip” is an outmoded designation for CL):

And the blots of Nature’s hand

Shall not in their issue stand;

Never mole, hare lip, nor scar,

Nor mark prodigious, such as are

Despised in nativity,

Shall upon their children be.

In King Lear (123, act 3, scene 4, lines 1911–13), Edgar describes the actions of a troublesome sprite:

He gives the web and the pin,

squints the eye, and makes the harelip; mildews the white wheat,

and hurts the poor creature of earth.

2. BACKGROUND

OFCs comprise any cleft (i.e., a break or gap) in orofacial structures. Owing to disruptions in various developmental processes, clefts can occur in the eyes, ears, nose, cheeks, and forehead as well as in the lips and palate. In total, approximately 15 different types of facial clefts have been observed and annotated [e.g., with the Tessier classification system (133)], but aside from CL and CP, most such clefts are extremely rare.

Most OFC research has focused primarily on CL and/or CP, and these are also the focus of this review. The majority of OFC—approximately 70% of CL with or without CP (CL/P) and 50% of CP (64)—is considered nonsyndromic, i.e., consisting of isolated anomalies with no other apparent cognitive or structural abnormalities. The nonsyndromic designation is therefore arbitrary and to some extent reflects our current lack of certainty about OFC etiologies (65). Since the advent of the many molecular tools available in our current era of genomics, many of the genetic variants or mutations causing syndromic forms of OFC have been identified (for further details, see box 1 in Reference 38 and the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim). Although there has also been much recent progress in identifying putative causal associations with nonsyndromic OFC, because of its etiologic complexity, less definitive progress has been made in nonsyndromic than syndromic anomalies. Therefore, this review focuses on the state of knowledge regarding the genetics of isolated/nonsyndromic OFC. Owing to space constraints, it includes few references to the voluminous literature on teratogens and other environmental etiologies in OFC; for more information on these topics, readers are referred to reviews such as those of Murray (101) and Dixon et al. (38).

Lip and palate development occurs very early in embryogenesis, with the lip forming first (complete by week 6), followed by the palate (complete around week 13) (134). In normal development, a variety of tissues are in place by week 4: The frontonasal prominence, paired maxillary processes, and paired mandibular processes surround the oral cavity. By week 5, the nasal pits have fused to form the paired medial and lateral nasal processes. The lip has formed by the end of week 6—i.e., the medial nasal processes have merged with the maxillary processes to form the upper lip and primary palate. During week 6, bilateral outgrowths from the maxillary processes grow down on either side of the tongue to become the palatal shelves. The tongue then drops down and the palatal shelves elevate to above the tongue and fuse to form the palate, which is complete by week 12.

Because normal lip and palate development requires growth and fusion of the relevant structures, all human embryos have clefts of the lip and palate that must fuse to result in the normal structures. Disruptions at any stage of the developmental process can prevent the necessary fusions and result in OFCs at birth: These problems can include defects in the many steps required for fusion, or disruption of the timing and/or positioning of the processes and/or palatal shelves (e.g., in Pierre Robin sequence, in which micrognathia prevents the tongue from dropping).

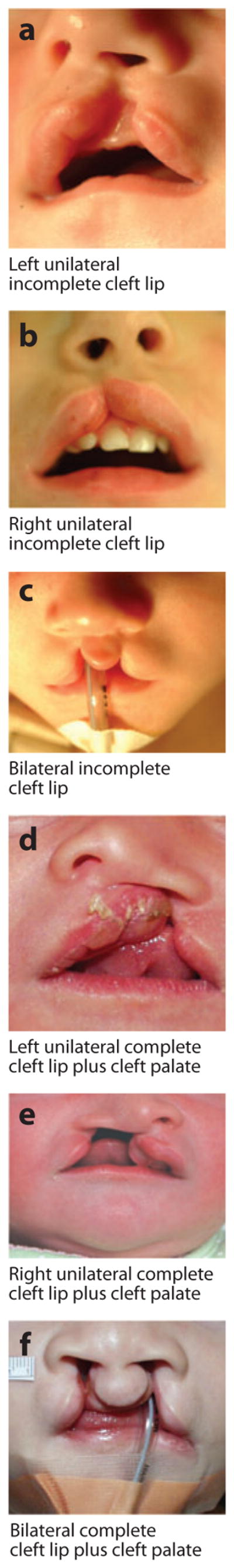

OFC has a wide range of expression and severity, from CL alone (e.g., Figure 1a–c) to CL plus CP (CLP) (Figure 1d–f) to CP alone (Figure 1g–j). This wide range represents a particular challenge, and, as reviewed in Section 3.4.4 below, there is also evidence that minor defects (either microforms or subclinical physical features within the range of normal development—see, e.g., Figure 2) are also part of the spectrum of OFC. CL/P and CP alone have historically been considered separate etiologic entities owing to the developmental origins of the structures as well as the epidemiology and family patterns of the two groups (45, 46). CP is more likely to be syndromic than CL/P; note that most etiologic studies have focused on CL/P.

Figure 1.

Examples of overt types of orofacial clefts. Photographs courtesy of M. Ford, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Cleft-Craniofacial Center, through FaceBase (http://www.facebase.org).

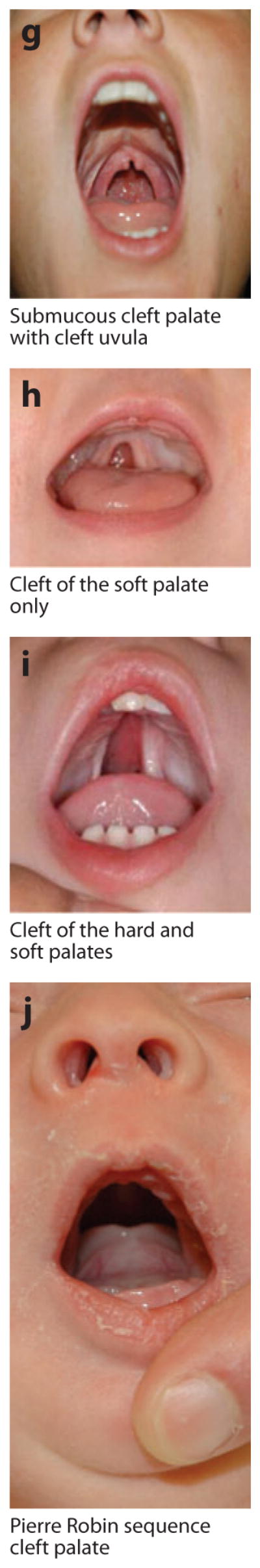

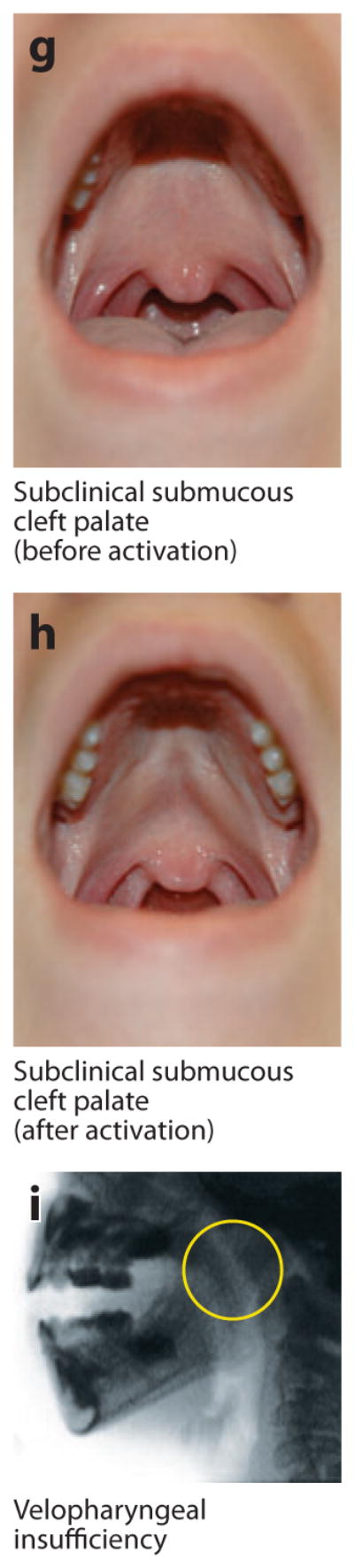

Figure 2.

Examples of microform and subclinical phenotypes. (a) Normal orbicularis oris muscle visualized via high-resolution ultrasound in a cross section through the upper lip. Note the wide, uniform appearance of the muscle and contrast with the breaks seen in panel b. (b) Orbicularis oris muscle with subclinical (i.e., not externally visible) defects that appear as breaks in the muscle. This image shows bilateral breaks (circled), which, notably, are located where overt clefts of the lip would be. (c–f) Microform lip defects. (g–h) Subclinical submucous cleft palate (i.e., not obvious unless activated by appropriate speech sounds; these panels show the same individual before and after activation). (i) Velopharyngeal insufficiency visualized with videofluoroscopy. Note the wide velopharyngeal gap (circled). Photographs in panels c–i courtesy of M. Ford, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Cleft-Craniofacial Center, through FaceBase (http://www.facebase.org).

The epidemiology of OFC has a number of striking features. Notably, there are both ethnic and gender differences in the birth prevalence of CL/P. Native Americans and Asians have the highest rates (close to 2 per 1,000 live births), Caucasians an intermediate rate (approximately 1 per 1,000), and African-derived populations the lowest rates (approximately 1 per 2,500) (28, 32, 99, 100). There is a 2:1 male:female ratio for CL/P, but an approximately 1:1 male:female ratio for CP. OFC can be unilateral or bilateral; notably, the majority of unilateral clefts (approximately two-thirds) are on the left side (see Figure 1a,d).

In developed countries, routine surgical treatment with ongoing orthodontia, speech, and other therapies is very successful in ameliorating these anomalies (see sidebar History of Orofacial Cleft Surgery), but there is still a significant financial burden for individuals with OFC, their families, and society (12, 150). In addition, individuals with OFC are subject to difficulties with eating, speaking, hearing, and social engagement and increased risk of certain adult medical conditions, such as specific types of cancer (29, 37, 94). Given the high birth prevalence of OFC compared with other facial birth defects and the resulting personal and public issues, the causes of OFC have been a target of research investigation for centuries.

HISTORY OF OROFACIAL CLEFT SURGERY.

Today, surgical repair of CL is performed around 2–3 months of age, with CP closure performed at 6–12 months (for details, see http://www.acpa-cpf.org/team_care). The earliest written account of a cleft surgery is from ancient China; the annals of the Chin dynasty from 390 AD recount the repair of CL in an 18-year-old man (18). Some of the features of the surgery (e.g., cutting and stitching the cleft edges) are essentially the same today, although various refinements now give more functional and aesthetic results. Surgical treatment of CP was first described in 1817 (143) and was followed by many years of refinement of surgical techniques. Given the dates of these early surgical methods, for many years OFC repair was done without the benefit of anesthesia, usually by binding the child tightly to a board for the ordeal. Today, there are many models for palate closure, but most still follow variations of the layered closure of the hard and soft palate as described by von Langenbeck in 1861 (144) and Veau in 1931 (139).

In the following sections, I (a) review the evolution of the approaches applied to OFC (from the pregenetics era through the genomics era) along with the insights gained from those approaches, (b) summarize the current state of knowledge, and (c) provide a perspective on challenges and future directions for research.

3. EVOLUTION OF HUMAN GENETIC STUDIES OF OROFACIAL CLEFTS

3.1. Pregenetics Era

Interest in the causes of OFC goes back thousands of years and continues to the present. For the purposes of this review, the pregenetics era comprises the years leading up to approximately 1900, when Mendel’s research (93) was rediscovered, translated, and championed by Bateson (6, 7, 91).

3.1.1. Folklore explanations

There is no way to know when facial birth defects such as OFC first arose, although it certainly predated the written word. From very early in human history there was interest in OFC birth defects and speculation about the causes of such anomalies. This speculation resulted in a number of folklore explanations of how OFC arises and how to prevent occurrence during pregnancy, some of which survive to the present day (34). Notable examples come from two populations with a high birth prevalence of OFC: native South Americans and Asians.

The Aztecs believed that eclipses occurred because a bite had been taken out of the moon, and so exposure to an eclipse during pregnancy could lead to OFC (a bite out of the infant’s mouth). This folklore extends to modern Mexico, with the addition of exposure to a full moon. To prevent OFC, the Aztecs placed an obsidian knife on the pregnant woman’s abdomen before going out at night; today, in Mexico, a metal key or safety pin is used for protection.

In China there was a common belief that eating rabbit during pregnancy could lead to a “hare lip” (an outmoded term for CL), an idea still held by some modern Chinese Americans (24). Other traditional explanations in China arose from Buddhist teachings that fate or bad karma leads to deformities, or that deformities are retributions for wrongdoings (24). When Daack-Hirsch and colleagues (34) surveyed modern-day Filipinos, the most frequent cause mentioned for OFC was “force to the fetal face” due to force applied to the pregnant abdomen during a fall or other maternal injury when the fetus had fingers or a thumb in the oral cavity, thus causing the cleft.

In addition to such folkloric explanations, which have since been discounted by modern scientists, it is notable that many cultures felt that OFC is familial—e.g., “in the blood” (24, 34)—which we still agree with today.

3.1.2. Descriptive family studies

The notion that OFC is familial eventually led to published descriptive or observational family studies; the first publication came in 1757 (136) and concerned a family with several affected members. More than a century later, Darwin (36) cited a paper by Sproule (128) and mentioned “the transmission during a century of hare-lip with a cleft-palate” in his discussion of variation in plants and animals. Notably, as was also the case during other paradigm shifts in human genetics, OFC was a prominent example brought forth by Darwin and others. Additional pre-1900 publications and OFC pedigrees were summarized by Rischbieth (91, 117).

3.2. Dawn of Genetics

The dawn of genetics as a scientific discipline began in the early 1900s, with the debates of Mendel proponents such as Bateson against Pearson and the other members of the Galton laboratory (for detailed commentary on the role OFC played in this debate, see 91). Of note is that OFC was used as an example by both sides of the debate, a pattern that continued at other times of paradigm shift in human genetics (see below). The anti-Mendelian view of the Galton laboratory was expressed by Rischbieth’s conclusion that OFC was an expression of general “physical and racial degeneracy” traced to poor protoplasm (91, 117), which would now be considered essentially a polygenic or multifactorial model for OFC. On the Mendelian side of the debate, Bateson included “hare-lip” as one of a group of “dominant hereditary diseases and malformations” (7, 91).

The early years of the twentieth century settled part of the debate in favor of Mendel’s principle of unit inheritance, with the units now known as genes. However, both partners in this debate were partially correct in that today we consider OFC to be heterogeneous, with single genes of major effect (as in Darwin’s and Bateson’s conclusions) potentially modified by polygenic background and environmental/behavioral factors (as in the Galton laboratory’s viewpoint). Rischbieth (91, 117) also set the stage for many subsequent family studies of OFC:

The cause of these defects [OFCs] lies in the family tendency, but it is only when the family is considered as a whole, in all its branches and when normal as well as deformed individuals are included in the records, that we shall begin to understand the mode of working of the hereditary influence. … [I]n the case of harelip and cleft palate inquiry has usually gone no further than to ask how many relatives (usually in the direct line) showed this defect (117).

3.3. Genetics Era (Pregenomics)

The genetics era (pregenomics) began in approximately 1910 with the development of a wide range of statistical tools for genetic analysis in families (segregation analysis and linkage analysis), included the development of cytogenetic methods and the beginnings of molecular genetics in the 1980s and 1990s, and ended around 2000 with the success of the Human Genome Project (HGP).

3.3.1. Early applications of statistics to OFC

A particular model termed the multi-factorial threshold (MFT) model was said to explain the unique epidemiological features of OFC, and early statistical tests of OFC involved descriptive studies that either concluded that the family data were consistent with MFT without performing statistical tests (e.g., 22, 159) or tested MFT predictions (e.g., 92, 127); however, testing the predictions of a model does not constitute a formal statistical test of that model. In this case, although predictions under the MFT model can explain some of the epidemiological features of OFC, other models can have similar predictions. The development of segregation analysis methods allowed statistical model testing.

3.3.2. Segregation analysis

Some of the most important statisticians utilized examples from genetics in the early development of statistics and probability. For example, Weinberg (of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium fame) developed methods to remove the ascertainment bias in the estimation of segregation ratios in siblings—the Weinberg proband method (157)—with standard error formulas derived by Fisher (43) and the addition of likelihood methods to estimate parameters by Haldane (53). By the 1970s, segregation analysis had evolved to allow hypothesis tests of a larger variety of models, and the early 1970s through the early 1990s saw a large number of segregation analyses of OFC in a variety of ethnicities, including US and European Caucasians (e.g., 57, 88), Asians and mixed Asians (e.g., 31, 85), and others. A 2002 review of published segregation analyses of OFC (83) concluded that in most populations the results were consistent with genes of major effect operating in the etiology of OFC, sometimes with evidence of multifactorial background effects (see also sidebar Segregation Analysis and Orofacial Clefts). This conclusion provided critical impetus to the subsequent successful gene-finding efforts for OFC. Also consistent with these results were analyses based on evaluations of recurrence risk in OFC families, which in the aggregate estimated that from 2 to 15 genes of major effect are likely involved in OFC (30, 120).

3.3.3. Systematic development of family data sets

Applying any statistical genetic method requires large numbers of families or large numbers of cases and controls for sufficient statistical power. Compared with other similarly complex human traits, OFC is more amenable to the assemblage of large data sets of families for a number of reasons: The trait is evident at birth, approximately 20%–30% of probands have additional family history (50) (useful for approaches such as linkage analysis), and families of individuals with craniofacial anomalies tend to be motivated to assist research efforts. The pioneer in recruiting and characterizing families through OFC probands was Fogh-Andersen, who accumulated a large cadre of Danish families in 1942 (44) and paved the way for the important role that other Danish and Scandinavian researchers would later play in studies of OFC and other complex human disorders. During the latter part of the twentieth century, many research groups, separately and in collaboration, recruited large numbers of families that were extraordinarily useful for the methods of the genetics era (1, 9, 28, 57, 87) and, fortuitously, were similarly rich resources for the methods of the genomics era (9, 10, 14, 79).

3.3.4. Candidate genes (association and linkage studies)

The elucidation of DNA as the genetic molecule (147) midway through the twentieth century led to the field of molecular genetics and eventually genomics. Early molecular genetics advances were important for OFC because of the development of improved genetic markers (such as restriction fragment length polymorphisms and microsatellites) for family studies of candidate genes and for genome scans. Initial studies of candidate genes for OFC and other traits were done by utilizing non-DNA-based genetic markers such as the ABO blood group and HLA (assessed serologically) and employed statistical methods such as association analysis in case/control series or linkage analysis in multiplex families or affected relative pairs.

The first published association studies for OFC evaluated association with HLA alleles (16, 146), which were examined because susceptibility to cortisone-induced CP in some mouse strains was associated primarily with genotypes at the H2 locus (17). Although several studies were done in Caucasian and Asian populations, no overall positive associations were found between HLA and CL/P or CP. The first published positive association for OFCs was a population-based association between CL/P and a TaqI restriction site polymorphism in the transforming growth factor alpha locus (TGFA) (1). Linkage approaches were also applied in tests for candidate genes, again first evaluating HLA, with no positive results for either CP or CL/P (138). The first positive linkage with OFC was with F13A on chromosome 6p (39), in a study utilizing a subset of the multiplex Danish families first documented by Fogh-Andersen (44).

There were many other candidate gene studies throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s (for recent reviews of those studies, see 67, 101). Although many genes/regions had positive results in one or more of the early studies, few of those findings were consistently positive across all studies, primarily owing to a lack of adequate sample size. In addition to the previously mentioned TGFA and F13A, the following had at least one positive linkage or association result with OFC during this time period: interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6; chromosome 1q32.3-q41), homeobox 7 (MSX1; 4p16), anonymous markers on 4q31, transforming growth factor beta-3 (TGFB3; 14q24), retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA; 17q21), and proto-oncogene BCL3 plus nearby anonymous markers (19q13).

In the late 1990s, highly polymorphic microsatellite genetic markers (alleles defined by differing numbers of short tandem repeats of DNA sequence) were identified across the genome and allowed the first genome-wide scans via linkage analyses of affected relative pairs or multiplex families. OFC researchers immediately began applying those methods.

3.3.5. Genome-wide linkage studies

Eleven years after the first positive linkage and association results for individual candidate genes and OFC, the twenty-first century was ushered in with the first genome-wide linkage scan for loci involved in CL/P in affected English sibling pairs (113), which was followed by a scan in extended multiplex Chinese kindreds (84). Multiple other genome-wide linkage scans were performed for CL/P, each of which noted a number of positive signals; however, owing to limited sample size, few individual study results reached the standard levels of genome-wide significance [LOD scores ≥ 3.2 (73) for the typical 400-microsatellite-marker panel] until a consortium of research groups pooled their studies and achieved the first genome-wide significant results for CL/P in regions 1q32, 2p, 3q27-28, 9q21, 14q21-24, and 16q24 (86, 87). Follow-up fine mapping of these regions showed significant results for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in IRF6, which had been previously associated in candidate gene studies (114) and was later also identified by genome-wide association studies (9, 13, 79), and in FOXE1, which was later confirmed and strengthened with the results in other populations and from expression studies (78, 96, 107, 140).

3.3.6. The human genome project begins

Following the explosion of molecular genetics tools during this time, a grand concept took shape to determine the full sequence of the human genome. The planning stages for what became the HGP were laid by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during the late 1980s and 1990s, and the project officially began on October 1, 1990. Human genetic sequencing had begun by April 1996, was finished in 2000, and was documented in a series of papers in the February 15, 2001, issue of Nature (vol. 409, issue 6822; see, e.g., 5, 74), thus ushering in the genomics era.

3.4. Genomics Era

Following the successful completion of the HGP in 2000, the twenty-first century has clearly been the genomics era—distinguished from the genetics era by the concentration on research tools made possible by the HGP and/or required for maximal utilization of the HGP information. Some of the key tools now available include databases such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information databases, the UCSC Genome Browser, and the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE); genetic markers with high throughput such as SNPs and copy number variants (CNVs); improved high-throughput sequencing such as whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing; subprojects such as the International HapMap Project and the 1000 Genomes Project; and tailored statistical approaches such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which generally utilize SNPs along with imputation to infer genotypes at nongenotyped base pairs in a study population. The availability of these tools has led to a key paradigm shift in human genetics: Before such tools were developed, the greatest attention and success in human gene searches were in identifying rare variants causing Mendelian (single-gene) traits. The new genomics tools are ideal for dissecting common, complex (non-single-gene) traits such as OFC, and OFC researchers have embraced these tools. Here I summarize the major findings for OFC across the first decade of the genomics era.

SEGREGATION ANALYSIS AND OROFACIAL CLEFTS.

One of the first genetic methods applied to human family data was segregation analysis—the statistical methods used to determine the mode of inheritance of a trait. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/174893?redirectedFrom=segregation#eid), the first use of the term segregation in a genetics context was by Weldon in 1902 (158) in a paper describing Mendel’s laws regarding the segregation of alleles in gamete formation. Thus, segregation analysis was originally a technique to test Mendelian patterns, but it later grew to encompass tests of a variety of transmission modes in human family data (40, 71, 72, 75, 97, 98). Importantly for OFC, the advent of mixed model analyses (72) in the 1970s provided an integrated framework with both major gene and multifactorial components, thus allowing explicit nested contrasts between the prevailing notion of the MFT model for OFC and models including major gene inheritance. The consensus from a large number of OFC segregation analyses (83) was that in most populations the family data were consistent with major genes for OFC operating on a multifactorial background. The segregation analysis results have since been convincingly supported by the current success in identifying multiple genetic loci for OFC.

3.4.1. Genome-wide association studies

GWAS have now been used to study a large number of common, complex disorders, most of which are adult onset and have a complicated etiology. OFC is one of the few birth-onset disorders to have been studied with the GWAS method. So far there have been a number of GWAS for CL/P (9, 14, 47, 79) and one for CP (10). These studies have been extremely successful in that they identified multiple genome-wide significant associations with CL/P and identified potential gene-environment interactions for CP.

The first successful OFC GWAS (14) used a Caucasian CL/P case/control sample, confirmed IRF6 [1q32.3-q41, which had prior positive candidate gene (13, 66, 114) and linkage analysis (86) results] as associated, and, notably, identified a novel region on chromosome 8q24 with extremely strong evidence of association. An expanded study increased the sample size and added replication populations (79). The results confirmed 8q24 and IRF6 as associated and also identified two additional loci: 17q22 near NOG and 10q25.3 near VAX1. The overall population-attributable risk was estimated as approximately 54.6% for the four best-supported loci (IRF6, 8q24, 17q22, and 10q25.3)—i.e., unlike many other common, complex human traits that are under study (82), the results from CL/P GWAS have yielded loci potentially capable of explaining a substantial portion of the variation in CL/P.

The 8q24 region was confirmed by a subsequent Caucasian case/control GWAS (47) as well as a nuclear-trio-based GWAS of Caucasians and Asians (9) that was part of the trans-NIH Gene-Environment Association Studies (GENEVA) study (33). In the latter study, there were interesting differences between the strength of association seen in the two ethnicities, apparently due to lower minor allele frequencies in Asians compared with Caucasians. Notably, the statistical evidence for IRF6 variants was strongest in the Asians, whereas the evidence for 8q24 was strongest in the Caucasians. The GENEVA study also identified at least two novel loci (near MAFB and ABCA4) that reached genome-wide significance, with stronger signals in the Asians than in the Caucasians.

As with other etiologic investigations of OFC, there has been a dearth of CP GWAS. In the European CL/P GWAS (14, 79), the replication panel of SNPs for the four best-supported loci was also tested in CP trios and showed no statistically significant results, implying little or no overlap in the findings for CL/P versus CP. The first CP GWAS was recently performed (10) and found no genome-wide significant signals until gene-environment interaction models were applied (incorporating three common exposures during pregnancy: maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and multivitamin supplementation). Significant gene-environment interaction results included MLLT3 and SMC2 on chromosome 9 with alcohol consumption, TBK1 on chromosome 12 and ZNF236 on chromosome 18 with maternal smoking, and BAALC on chromosome 8 with multivitamin supplementation (10).

3.4.2. Comparison of GWAS and genome-wide linkage results

Interestingly, with the notable exception of IRF6, the significant signals to date from GWAS of CL/P are different than the significant signals from genome-wide linkage analyses. This fact emphasizes that the two approaches have different strengths: Association studies are more sensitive than linkage studies in detecting common variants of small effect size, but linkage studies are more robust in detecting etiologic genes that exhibit allelic heterogeneity—if multiple different variants (especially rare variants) within a gene can lead to OFC, linkage is much more likely to detect such genes (116). Further, it is important to remember that the study samples differ for the two approaches. For linkage approaches, multiplex families are necessary (either extended kindreds or affected relative pairs); for association approaches, the most common study samples are either case/control series or nuclear trios. Thus, the linkage studies were enriched in familial cases, which make up approximately 20%–30% of CL/P samples, and the association studies were enriched in sporadic cases. GWAS have now identified multiple loci that may represent as much as 55% of the variation in CL/P; the mostly nonoverlapping genome-wide linkage results imply that some of the remaining variation may be due to rare variants, CNVs, or other types of variation in the etiologic genes or regulatory regions of the risk genes.

3.4.3. Sequencing and -omics in OFC

There have been multiple targeted sequencing studies of candidate genes for CL/P that have identified potentially etiologic variants (62, 141). With the recent successes from genome-wide linkage and association studies (see Table 1), researchers are currently applying both whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing under the significant peaks, and in the next year or two they should begin to identify new variants for OFC. Because of the costs, to date these approaches have been applied only to Mendelian traits, including some syndromes that can include OFC [e.g., Miller syndrome (105) and Kabuki syndrome (104)]. Now that the costs have become more reasonable, though, whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing studies of common, complex traits, including OFC, have begun.

Table 1.

Summary of genomic regions with genomic-wide significant results and the genes in those regions that are best supported by additional evidence

| Genomic region | Reference(s) for genome-wide significance | Selected recent reference(s) supporting candidate gene | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide linkage | Genome-wide association | Candidate gene in region | Replicationa or prior candidate gene analysisb | Expression or functional analysis | Syndromes with orofacial cleft as a feature that are caused by mutations in the candidate genec | |

| 1p22.1-31 | 81 | 9 | ABCA4 | 9 | ||

| 1q32 | 86 | 9, 14, 79 | IRF6 | 9, 13, 15, 23, 60, 66, 86, 112, 114 | 14, 41, 61, 114, 145 | Van der Woude, popliteal pterygium |

| 2p13 | 86 | TGFA | 1, 8, 23, 25, 95, 131 | |||

| 3q27-28 | 86 | TP63 | 69, 76 | 11, 135, 137 | Ankyloblepharon–ectodermal dysplasia–clefting, ectrodactyly–ectodermal dysplasia–clefting, Hay-Wells | |

| 8q24 | 9, 14, 47, 79 | Gene desert | 9, 106, 119 | |||

| 9q21 | 86 | FOXE1 | 78, 81, 96 | 96 | Bamforth-Lazarus | |

| 10q25.3 | 9, 79 | VAX1 | 54, 126 | |||

| 14q21-24 | 86 | BMP4 | 81, 121, 130, 132 | 3, 4, 56, 63, 68, 160 | ||

| 16q24 | 86 | CRISPLD2 | 26, 27, 77, 124, 125 | 26, 77 | ||

| 17q22 | 79 | NOG | 2, 56 | |||

| 20q12 | 9 | MAFB | 9, 81 | 9, 129 | ||

Positive replication of marker results in additional populations, sometimes using the same markers found in the genome-wide studies and sometimes using additional markers in the genome-wide significant region.

Association or sequencing.

For further details about these syndromes, see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim.

There are also other “-omics” approaches that have yet to be applied to OFC on the large scale now possible, including epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, but given the history of the application of pertinent new methods to OFC, it is likely to be only a matter of time until they are. Researchers are already actively applying the principles of phenomics (i.e., expanded phenotyping) in OFC, as is reviewed in the next section.

3.4.4. Phenotyping/phenomics

It has long been appreciated that accurate phenotyping is essential for successful human genetic studies, as exemplified in the debates between “lumpers” and “splitters” from the 1960s and 1970s (90). There has been an explosion of bioinformatic tools and resources related to phenotyping, in part motivated by the HGP (74). Examples include PhenomicDB (51, 52), GEN2PHEN (150), the PhenX Toolkit (55), and FaceBase (specific to OFC and other craniofacial anomalies) (58).

There is clearly a need to further examine the genetic findings in OFC to determine whether the various overt clinical phenotypes (Figure 1) are due to the same or different genetic etiologies. Some studies have begun to examine specific clinical phenotypes; e.g., genome-wide linkage results have differed depending on the types of phenotypes seen in multiplex families (86), and a specific putatively etiologic variant in IRF6 shows greater statistical significance in CL alone than in CLP (114). Further, as reviewed above, most variants identified as associated with CL/P do not also associate with CP (lending some strength to the historical division of OFC into CL/P versus CP, although note that CP studies to date have had relatively small sample sizes).

In addition to the overt clinical phenotypic spectrum, there are also visible microforms observed for the lip (Figure 2c–f) and palate (Figure 2g,h). Notably, there has been an increasing amount of research on subclinical phenotypic features—i.e., features within the range of normal variability that are seen at increased frequency in individuals with OFC or their relatives, as opposed to controls with no family history of OFC (155). The earliest studies were on features related to laterality, such as handedness (115, 155), whereas more recent studies have implicated a range of subclinical phenotypes, such as orbicularis oris muscle defects (Figure 2a,b) (35, 89, 103, 118), dental anomalies (142), lip dermatoglyphics (102), facial measurements (152–154, 156), brain variants on MRI (108–111), bifid uvula and submucous CP (Figure 2g,h), and velopharyngeal insufficiency (Figure 2i). Such features could represent the mildest physical expression of OFC risk genes (e.g., orbicularis oris or velopharyngeal insufficiency) and/or pleiotropic effects of the risk genes (e.g., lip dermatoglyphics).

Subclinical features that are increased in unaffected relatives may clarify the lack of typical Mendelian patterns seen in OFC families as well as the OFC discordance in monozygotic twins. Interestingly, a recent study of Danish twins found essentially identical recurrence risks for offspring of both the affected and the unaffected twin in discordant monozygotic pairs (48, 49). Furthermore, examination of such phenotypes is beginning to blur the historical distinction between CL/P and CP in some cases; e.g., in a small study, there was a significant proportion of CP cases with orbicularis oris defects (151).

4. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Given that OFC has been under formal scientific scrutiny since 1757, it is remarkable that a major conclusion from the pregenetics era has remained consistent throughout the years: that OFCs are familial and inherited. Other conclusions from the dawn of genetics through the genomics era have been more fluid—e.g., MFT as an explanatory model for OFC and the multiple positive candidate gene results that were not consistent across studies. OFC is certainly multifactorial in that there are multiple factors involved in OFC etiology, but the specific MFT statistical model that had been invoked does not fit the data well. The genetics and genomics eras provided the tools necessary to address OFC in a genome-wide fashion, leading to extraordinary progress in the past decade in identifying genes likely to prove etiologic for OFC (particularly for CL/P; fewer studies have been done to date for CP).

Table 1 summarizes those regions for which genome-wide significant results exist from either linkage or association genome scans. Also listed are candidate genes for each region, whether each has been confirmed (by replication, sequencing, functional, and/or expression studies), and whether mutations in the candidate gene lead to a Mendelian syndrome with OFC as a feature. Note that there are two regions not listed (4p21-26 and 12p11) that were implicated by genome-wide linkage analyses but do not yet have any confirmatory studies.

The best-supported candidate gene, with positive results from each listed criterion, is IRF6 (1q32.3-q41), which had been first identified as the etiologic gene in Van der Woude syndrome (70). Association with specific IRF6 variants has been seen in many diverse populations, and at least one etiologic variant has been documented. Animal models have started to provide insights into the molecular pathogenesis of IRF6 in OFC (for references, see Table 1). The 8q24 region highlights the potential for GWAS to identify a previously unknown relationship to CL/P; this region achieved the highest levels of statistical significance in multiple GWAS, with the strongest signals in Caucasians (as opposed to less significance in Asians, although this may be due to the markers being less informative in Asians). Despite initial forays (14), the etiologic variant(s) within the 8q24 region remain unknown, and thus the functional mechanism also remains to be elucidated. Intriguingly, given that OFC families appear to have higher rates of cancers (37, 94), SNPs in 8q24 are also strongly associated with familial cancers, notably colorectal and prostate cancer.

The other regions and candidate genes listed in Table 1 have less confirmatory evidence than IRF6 and 8q24, and multiple lines of research are currently under way to accumulate support. Note that for the 1p22 region, ABCA4 was evaluated as a possible candidate, but neither sequencing of the exons nor expression in mouse embryos supported ABCA4(9). Thus it is less likely to be the etiologic gene; there are multiple possible candidates in this region, so attention is now turning to other possibilities, such as ARHGAP29 (80). Another interesting feature that can be seen in Table 1 is that, with the exception of IRF6, no region was detected by both association and linkage methods—not surprising, given the different strengths of the two approaches. Further, there are many other genes that were implicated by early association and linkage studies and/or animal models that are not yet confirmed. Therefore, there is clearly additional variation to be found in OFC as researchers move to identify rare variants of different types.

Other important results to date include that there may be different genetic factors for different overt cleft phenotypes (Figure 1) and that subclinical features may also be important in understanding the function of the etiologic variants identified, or indeed in increasing our power to identify etiologic variants. The significant concentration of subclinical features in OFC families versus controls can explain why a deleterious congenital anomaly has survived in the population and why OFC families show reduced penetrance (including reduced monozygotic twin concordance), and may allow us to determine factors that prevent full expression of OFC risk genes.

5. FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CHALLENGES

The major challenge and main future direction for OFC genetic investigations are to move from the significant genome-wide results to identification of causative variants, both common and rare. Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing projects are now under way, and additional methods will be applied as they become available. Investigators also hope to understand the role that subtle CNVs (detectable only via molecular methods) play in OFC. Given that multiple larger CNVs lead to phenotypes that include OFC (see, e.g., 19, 20), it is to be expected that subtle defects may do the same. It is becoming clearer that the OFC risk genes do not work in a vacuum but rather interact with other risk genes and environmental factors, so the importance of applying new pathway analysis and identification methods cannot be overstated. Finally, animal models will continue to be key in expression and functional studies following statistically successful human studies; genomic resources such as FaceBase (58) hope to provide improved integration of animal model and human genetic results for OFC.

In this search for causative variants, both overt and subclinical phenotyping should be employed. There has been substantial investment in CL/P genetics, and similar effort should be applied to CP. It is hypothesized that for many OFC risk genes there will be certain phenotypic features that characterize that gene, and the first step in determining those features is careful phenotyping. Animal models should assist with this phenotyping effort as well, given that the phenotypes associated with sophisticated genetic manipulations can be recorded across a very large number of constructed individuals, pointing out new phenotypes to examine and/or new genes to investigate for particular phenotypes.

The successful completion of variant identifications is likely to lead to new ways to designate phenotypic patterns in terms of the responsible risk gene. Taking IRF6 as an example: Mutations in this gene cause Van der Woude syndrome, common polymorphic variants are associated with nonsyndromic CL/P (particularly CL alone), and rare variants are currently under scrutiny. Perhaps lip pits and subclinical lip pits (i.e., lip dermatoglyphic patterns) will become the defining feature of the presence of IRF6 risk variants in a family and will greatly enhance our ability to estimate specific recurrence risks. Further, understanding variants can also lead to treatment implications.

Much progress has been made in Caucasian OFC genetics and some has been made in Asians and Central and South Americans, but there is a need to broaden the ethnicities investigated given the differing birth prevalences by ethnicity. In particular, few studies have been done in African-derived populations; given their low birth prevalence, results from such populations could provide particular insights into OFC. Two studies have tested the loci significant in Caucasians and Asians, with no significant findings to date (21, 148). Other questions come from OFC epidemiology features, such as, is there a difference in risk variants for multiplex versus sporadic cases? And is there a genetic difference leading to the observed laterality and gender differences?

From the very earliest years of human scientific research, OFC has been a topic of investigation and an example of successful applications of human genetics methods. That is certainly the case today, given the latest results that have come from applying genomics-era tools to this common, etiologically complex congenital anomaly, leading to multiple genome-wide significant results. Although we now know that eclipses are not in the etiologic pathways of OFC, we are still teasing out the exact functional mechanisms; continuing to apply the tools resulting from the HGP will eventually lead to a fuller understanding of OFC and improved information and clinical applications for affected individuals and their families.

SUMMARY POINTS.

OFC has been of formal scientific interest since at least the 1700s, and even that long ago was hypothesized to be familial and inherited.

OFC is now felt to be multifactorial in some sense, owing to its multiple genetic and nongenetic causes, but the specific MFT statistical model does not fit the data well.

OFC has been a major success in the application of genome-wide approaches to a common, complex disorder, given that there are multiple genome-wide significant regions identified (Table 1).

Of the significant regions, four (IRF6 on 1q32-41, 8q24, 17q22, and 10q25.3) have been estimated to account for almost 55% of the variation in CL/P, representing one of the highest proportions achieved for any common, complex disorder.

With the exception of IRF6, genome-wide association and linkage approaches have identified nonoverlapping regions, owing to the different strengths of each approach. This implies that additional variation should be identifiable through sequencing and other approaches to detect rare variants.

Given the wide range of overt and subclinical phenotypes that are now known to aggregate in OFC families, phenotyping is predicted to be key in future approaches to understand the expression of OFC risk genes.

FUTURE ISSUES.

The primary future issue is to continue to move from statistical genome-wide results to identification of the functional variants (both common and rare) in OFC risk genes and/or their regulatory regions.

Sequencing projects are now under way to begin to identify additional variants in the genome-wide significant regions.

With the wealth of data that the sequencing and genotyping projects will bring, it will be imperative to maximize the analysis of the data by pathway analyses and other methods to detect interactions (gene-gene and gene-environment) and more complex interplay between etiologic variants, the environment, and phenotypes.

Enhanced inclusion of phenotyping will be important in understanding the functions of identified risk variants and pathways.

There has been substantial progress in identifying risk genes for CL/P; similar approaches should be extended to CP as well, requiring a concerted effort to identify substantial numbers of nonsyndromic CP individuals and families.

Progress to date has been concentrated in studies of Caucasian and Asian OFC families; it will be important to broaden studies to other ethnicities (especially to African-derived populations) to better understand the notable ethnic differences in birth prevalence.

As additional progress is made, OFC categorizations should be revisited to develop a gene- and/or phenotype-centric classification system that would be less arbitrary than nonsyndromic versus syndromic.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank many colleagues for productive collaborations and inspired brainstorming sessions throughout the genetics and genomics eras. Much gratitude to Michael Melnick and Anne Spence, who first interested me in orofacial clefting as a research topic, and to Jeff Murray, who has been an exceptional collaborator. Thanks are also due to my many other mentors, collaborators, and staff in the United States and worldwide. This work is supported in part by NIH grants DE-016148 and U01-DE020057.

Glossary

- OFCs

orofacial clefts, comprising clefts of the lip and/or palate

- CL

cleft lip (see Figure 1a–c); note that “harelip” is an outmoded term for cleft lip

- CP

cleft palate, i.e., cleft of the hard palate, soft palate, or both (see Figure 1g–j)

- CL/P

cleft lip with or without cleft palate (see Figure 1a–f)

- Micrognathia

unusual smallness of the jaws, especially the lower jaw; it can lead to Pierre Robin sequence, which results in a characteristically wide, U-shaped cleft of the palate (see Figure 1j)

- CLP

cleft lip plus cleft palate (see Figure 1d–f)

- Multifactorial threshold (MFT) model

statistical model for the etiology of traits that assumes the presence of a large number of factors (each of equal and additive effect) before an organism is affected

- Recurrence risk

the probability that a relative of an affected person will also be affected

- Genetic markers

molecules with a known chromosomal/genomic location that can be measured in study subjects and used to map the location of a trait of interest through association or linkage analyses

- Candidate genes

genes or sometimes genetic regions that are implicated a priori (from animal models or other evidence) as potential candidates for involvement in causing a trait of interest

- Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

biallelic genetic marker with a known base pair location

- CNVs

copy number variants, such as deletions, insertions, or duplications

- Velopharyngeal insufficiency

insufficient or incomplete closure of the soft palate muscle (velopharyngeal sphincter) during speech (see Figure 2i)

Footnotes

RELATED RESOURCES

1000 Genomes Project: http://www.1000genomes.org

American Cleft Palate–Craniofacial Association: http://www.acpa-cpf.org

Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium: http://www.encodeproject.org

FaceBase Consortium: http://www.facebase.org

GEN2PHEN: http://www.gen2phen.org

International HapMap Project: http://www.hapmap.org

National Center for Biotechnology Information: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim

PhenomicDB: http://www.phenomicdb.de

UCSC Genome Browser: http://www.genome.ucsc.edu

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The author is not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Ardinger HH, Buetow KH, Bell GI, Bardach J, VanDemark DR, Murray JC. Association of genetic variation of the transforming growth factor-alpha gene with cleft lip and palate. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;45:348–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashique AM, Fu K, Richman JM. Endogenous bone morphogenetic proteins regulate outgrowth and epithelial survival during avian lip fusion. Development. 2002;129:4647–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baek JA, Lan Y, Liu H, Maltby KM, Mishina Y, Jiang R. Bmpr1a signaling plays critical roles in palatal shelf growth and palatal bone formation. Dev Biol. 2011;350:520–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakrania P, Efthymiou M, Klein JC, Salt A, Bunyan DJ, et al. Mutations in BMP4 cause eye, brain, and digit developmental anomalies: overlap between the BMP4 and hedgehog signaling pathways. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:304–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltimore D. Our genome unveiled. Nature. 2001;409:814–16. doi: 10.1038/35057267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateson W. Mendel’s Principles of Heredity: A Defense. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateson W. Mendel’s Principles of Heredity. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaty TH, Hetmanski JB, Fallin MD, Park JW, Sull JW, et al. Analysis of candidate genes on chromosome 2 in oral cleft case-parent trios from three populations. Hum Genet. 2006;120:501–18. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaty TH, Murray JC, Marazita ML, Munger RG, Ruczinski I, et al. A genome-wide association study of cleft lip with and without cleft palate identifies risk variants near MAFB and ABCA4. Nat Genet. 2010;42:525–29. doi: 10.1038/ng.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaty TH, Ruczinski I, Murray JC, Marazita ML, Munger RG, et al. Evidence for gene-environment interaction in a genome wide study of nonsyndromic cleft palate. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:469–78. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaudry VG, Pathak N, Koster MI, Attardi LD. Differential PERP regulation by TP63 mutants provides insight into AEC pathogenesis. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1952–57. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berk NW, Marazita ML. Costs of cleft lip and palate: personal and societal implications. In: Wysznyski DF, editor. Cleft Lip and Palate: From Origin to Treatment. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press; 2002. pp. 458–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birnbaum S, Ludwig KU, Reutter H, Herms S, de Assis NA, et al. IRF6 gene variants in Central European patients with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:766–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birnbaum S, Ludwig KU, Reutter H, Herms S, Steffens M, et al. Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24. Nat Genet. 2009;41:473–77. doi: 10.1038/ng.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanton SH, Burt A, Garcia E, Mulliken JB, Stal S, Hecht JT. Ethnic heterogeneity of IRF6 AP-2a binding site promoter SNP association with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010;47:574–77. doi: 10.1597/09-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonner JJ, Terasaki PI, Thompson P, Holve LM, Wilson L, et al. HLA phenotype frequencies in individuals with cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Tissue Antigens. 1978;12:228–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1978.tb01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonner JJ, Tyan ML. Backcross test demonstrates the linkage of glucocorticoid-induced cleft palate susceptibility to H-2. Teratology. 1982;26:213–16. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420260214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boo-Chai K. An ancient Chinese text on a cleft lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;38:89–91. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brewer C, Holloway S, Zawalnyski P, Schinzel A, FitzPatrick D. A chromosomal deletion map of human malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1153–59. doi: 10.1086/302041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewer C, Holloway S, Zawalnyski P, Schinzel A, FitzPatrick D. A chromosomal duplication map of malformations: regions of suspected haplo- and triplolethality—and tolerance of segmental aneuploidy—in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1702–8. doi: 10.1086/302410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butali A, Mossey PA, Adeyemo WL, Jezewski PA, Onwuamah CK, et al. Genetic studies in the Nigerian population implicate an MSX1 mutation in complex oral facial clefting disorders. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48:646–53. doi: 10.1597/10-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter CO, Evans K, Coffey R, Roberts JA, Buck A, Roberts MF. A three generation family study of cleft lip with or without cleft palate. J Med Genet. 1982;19:246–61. doi: 10.1136/jmg.19.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter TC, Molloy AM, Pangilinan F, Troendle JF, Kirke PN, et al. Testing reported associations of genetic risk factors for oral clefts in a large Irish study population. Birth Defects Res A. 2010;88:84–93. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng LR. Asian-American cultural perspectives on birth defects: focus on cleft palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1990;27:294–300. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569(1990)027<0294:aacpob>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chevrier C, Bahuau M, Perret C, Iovannisci DM, Nelva A, et al. Genetic susceptibilities in the association between maternal exposure to tobacco smoke and the risk of nonsyndromic oral cleft. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2396–406. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiquet BT, Henry R, Burt A, Mulliken JB, Stal S, et al. Nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate: CRISPLD genes and the folate gene pathway connection. Birth Defects Res A. 2011;91:44–49. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiquet BT, Lidral AC, Stal S, Mulliken JB, Moreno LM, et al. CRISPLD2: a novel NSCLP candidate gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2241–48. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen K. The 20th century Danish facial cleft population—epidemiological and genetic-epidemiological studies. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1999;36:96–104. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1999_036_0096_tcdfcp_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen K, Juel K, Herskind AM, Murray JC. Long term follow up study of survival associated with cleft lip and palate at birth. Br Med J. 2004;328:1405. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38106.559120.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen K, Mitchell LE. Familial recurrence-pattern analysis of nonsyndromic isolated cleft palate—a Danish Registry study. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:182–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung CS, Ching GH, Morton NE. A genetic study of cleft lip and palate in Hawaii. II Complex segregation analysis and genetic risks. Am J Hum Genet. 1974;26:177–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper ME, Ratay JS, Marazita ML. Asian oral-facial cleft birth prevalence. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:580–89. doi: 10.1597/05-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornelis MC, Agrawal A, Cole JW, Hansel NN, Barnes KC, et al. The Gene, Environment Association Studies consortium (GENEVA): maximizing the knowledge obtained from GWAS by collaboration across studies of multiple conditions. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:364–72. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daack-Hirsch S. Filipino explanatory models of cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010;47:122–33. doi: 10.1597/08-139_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dado DV, Kernahan DA. Anatomy of the orbicularis oris muscle in incomplete unilateral cleft lip based on histological examination. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;15:90–98. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198508000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darwin C. The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. Vol. 1. London: Murray; 1875. p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dietz A, Pedersen DA, Jacobsen R, Wehby GL, Murray JC, Christensen K. Risk of breast cancer in families with cleft lip and palate. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:167–78. doi: 10.1038/nrg2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eiberg H, Bixler D, Nielsen LS, Conneally PM, Mohr J. Suggestion of linkage of a major locus for nonsyndromic orofacial cleft with F13A and tentative assignment to chromosome 6. Clin Genet. 1987;32:129–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1987.tb03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elston RC, Stewart BW. A general model for the genetic analysis of pedigree data. Hum Hered. 1971;21:523–42. doi: 10.1159/000152448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fakhouri WD, Rhea L, Du T, Sweezer E, Morrison H, et al. MCS9.7 enhancer activity is highly, but not completely, associated with expression of Irf6 and p63. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:340–49. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feydeau G. La Puce á l’oreille [A flea in her ear] London: Herns; 1907. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisher RA. The effect ofmethods of ascertainment upon the estimation of frequencies. Ann Eugen. 1934;6:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fogh-Andersen P. Inheritance of Harelip and Cleft Palate. Copenhagen: NytNordisk Forlag/Arnold Busck; 1942. p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fogh-Andersen P. Epidemiology and etiology of clefts. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1971;7:50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraser FC. Thoughts on the etiology of clefts of the palate and lip. Acta Genet Stat Med. 1955;5:358–69. doi: 10.1159/000150783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant SF, Wang K, Zhang H, Glaberson W, Annaiah K, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on 8q24. J Pediatr. 2009;155:909–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grosen D, Bille C, Pedersen JK, Skytthe A, Murray JC, Christensen K. Recurrence risk for offspring of twins discordant for oral cleft: a population-based cohort study of the Danish 1936–2004 cleft twin cohort. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2468–74. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grosen D, Bille C, Petersen I, Skytthe A, Hjelmborg JB, et al. Risk of oral clefts in twins. Epidemiology. 2011;22:313–19. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182125f9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grosen D, Chevrier C, Skytthe A, Bille C, Molsted K, et al. A cohort study of recurrence patterns among more than 54,000 relatives of oral cleft cases in Denmark: support for the multifactorial threshold model of inheritance. J Med Genet. 2010;47:162–68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groth P, Leser U, Weiss B. Phenotype mining for functional genomics and gene discovery. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;760:159–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-176-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Groth P, Pavlova N, Kalev I, Tonov S, Georgiev G, et al. PhenomicDB: a new cross-species genotype/phenotype resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Suppl 1):D696–99. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haldane JBS. The estimation of the frequencies of recessive conditions in man. Ann Eugen. 1938;8:255–62. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hallonet M, Hollemann T, Pieler T, Gruss P. Vax1, a novel homeobox-containing gene, directs development of the basal forebrain and visual system. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3106–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:253–60. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He F, Xiong W, Wang Y, Matsui M, Yu X, et al. Modulation of BMP signaling by Noggin is required for the maintenance of palatal epithelial integrity during palatogenesis. Dev Biol. 2010;347:109–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hecht JT, Yang P, Michels VV, Buetow KH. Complex segregation analysis of nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49:674–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hochheiser H, Aronow BJ, Artinger K, Beaty TH, Brinkley JF, et al. The FaceBase Consortium: a comprehensive program to facilitate craniofacial research. Dev Biol. 2011;355:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hosseini K. The Kite Runner. New York: Berkeley Publ. Group; 2003. p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang Y, Wu J, Ma J, Beaty TH, Sull JW, et al. Association between IRF6 SNPs and oral clefts in West China. J Dent Res. 2009;88:715–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034509341040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ingraham CR, Kinoshita A, Kondo S, Yang B, Sajan S, et al. Abnormal skin, limb and craniofacial morphogenesis in mice deficient for interferon regulatory factor 6 (Irf6) Nat Genet. 2006;38:1335–40. doi: 10.1083/ng1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jezewski PA, Vieira AR, Nishimura C, Ludwig B, Johnson M, et al. Complete sequencing shows a role for MSX1 in non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. J Med Genet. 2003;40:399–407. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang R, Bush JO, Lidral AC. Development of the upper lip: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1152–66. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones MC. Etiology of facial clefts: prospective evaluation of 428 patients. Cleft Palate J. 1988;25:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones MC. Facial clefting. Etiology and developmental pathogenesis. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:599–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jugessur A, Rahimov F, Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, Gjessing HK, et al. Genetic variants in IRF6 and the risk of facial clefts: single-marker and haplotype-based analyses in a population-based case-control study of facial clefts in Norway. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:413–24. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jugessur A, Shi M, Gjessing HK, Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, et al. Genetic determinants of facial clefting: analysis of 357 candidate genes using two national cleft studies from Scandinavia. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ. Mouse genetic models of cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Birth Defects Res A. 2008;82:63–77. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kantaputra PN, Malaivijitnond S, Vieira AR, Heering J, Dotsch V, et al. Mutation in SAM domain of TP63 is associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate and cleft palate. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1432–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, Bjork BC, Knight AS, et al. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet. 2002;32:285–99. doi: 10.1038/ng985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lalouel JM, Morton NE. Complex segregation analysis with pointers. Hum Hered. 1981;31:312–21. doi: 10.1159/000153231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lalouel JM, Rao DC, Morton NE, Elston RC. A unified model for complex segregation analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35:816–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lander ES, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–47. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lange K, Westlake J, Spence MA. Extensions to pedigree analysis. II Recurrence risk calculation under the polygenic threshold model. Hum Hered. 1976;26:337–48. doi: 10.1159/000152825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leoyklang P, Siriwan P, Shotelersuk V. A mutation of the p63 gene in non-syndromic cleft lip. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e28. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Letra A, Menezes R, Cooper ME, Fonseca RF, Tropp S, et al. CRISPLD2 variants including a C471T silent mutation may contribute to nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48:363–70. doi: 10.1597/09-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Letra A, Menezes R, Govil M, Fonseca RF, McHenry T, et al. Follow-up association studies of chromosome region 9q and nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:1701–10. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mangold E, Ludwig KU, Birnbaum S, Baluardo C, Ferrian M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Nat Genet. 2010;42:24–26. doi: 10.1038/ng.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mangold E, Ludwig KU, Nothen MM. Breakthroughs in the genetics of orofacial clefting. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:725–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mangold E, Reutter H, Birnbaum S, Walier M, Mattheisen M, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan of nonsyndromic orofacial clefting in 91 families of central European origin. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2680–94. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marazita ML. Segregation analyses. In: Wyszynski DF, editor. Cleft Lip and Palate: From Origin to Treatment. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press; 2002. pp. 222–33. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marazita ML, Field LL, Cooper ME, Tobias R, Maher BS, et al. Genome scan for loci involved in cleft lip with or without cleft palate, in Chinese multiplex families. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:349–64. doi: 10.1086/341944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marazita ML, Hu DN, Spence MA, Liu YE, Melnick M. Cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Shanghai, China: evidence for an autosomal major locus. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:648–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marazita ML, Lidral AC, Murray JC, Field LL, Maher BS, et al. Genome scan, fine-mapping, and candidate gene analysis of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate reveals phenotype-specific differences in linkage and association results. Hum Hered. 2009;68:151–70. doi: 10.1159/000224636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marazita ML, Murray JC, Lidral AC, Arcos-Burgos M, Cooper ME, et al. Meta-analysis of 13 genome scans reveals multiple cleft lip/palate genes with novel loci on 9q21 and 2q32-35. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:161–73. doi: 10.1086/422475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marazita ML, Spence MA, Melnick M. Genetic analysis of cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Danish kindreds. Am J Med Genet. 1984;19:9–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320190104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martin RA, Hunter V, Neufeld-Kaiser W, Flodman P, Spence MA, et al. Ultrasonographic detection of orbicularis oris defects in first degree relatives of isolated cleft lip patients. Am J Med Genet. 2000;90:155–61. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000117)90:2<155::aid-ajmg13>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McKusick VA. On lumpers and splitters, or the nosology of genetic disease. Perspect Biol Med. 1969;12:298–312. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1969.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Melnick M. Cleft lip and palate etiology and its meaning in early 20th century England: Galton/Pearson versus Bateson; polygenically poor protoplasm versus Mendelism. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1997;17:65–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Melnick M, Bixler D, Fogh-Andersen P, Conneally PM. Cleft lip±cleft palate: an overview of the literature and an analysis of Danish cases born between 1941 and 1968. Am J Med Genet. 1980;6:83–97. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320060108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mendel G. Versuche uber pflanzenhybriden. Verhandenlungen Naturforschenden Vereines Brunn. 1866;4:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Menezes R, Marazita ML, McHenry TG, Cooper ME, Bardi K, et al. AXIS inhibition protein 2, orofacial clefts and a family history of cancer. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:80–84. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mitchell LE. Transforming growth factor alpha locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate: a reappraisal. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14:231–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1997)14:3<231::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moreno LM, Mansilla MA, Bullard SA, Cooper ME, Busch TD, et al. FOXE1 association with both isolated cleft lip with or without cleft palate, and isolated cleft palate. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4879–96. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morton NE. Genetic tests under incomplete ascertainment. Am J Hum Genet. 1959;11:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morton NE, MacLean CJ. Analysis of family resemblance. 3 Complex segregation of quantitative traits. Am J Hum Genet. 1974;26:489–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mossey PA. Epidemiology underpinning research in the aetiology of orofacial clefts. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2007;10:114–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mossey PA, Little J, Munger RG, Dixon MJ, Shaw WC. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. 2009;374:1773–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Murray JC. Gene/environment causes of cleft lip and/or palate. Clin Genet. 2002;61:248–56. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Neiswanger K, Chirigos KW, Klotz CM, Cooper ME, Bardi KM, et al. Whorl patterns on the lower lip are associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2673–79. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Neiswanger K, Weinberg SM, Rogers CR, Brandon CA, Cooper ME, et al. Orbicularis oris muscle defects as an expanded phenotypic feature in nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Am J Med Genet. 2007;143:1143–49. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, Hannibal MC, McMillin MJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42:790–93. doi: 10.1038/ng.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ng SB, Buckingham KJ, Lee C, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, et al. Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:30–35. doi: 10.1038/ng.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nikopensius T, Ambrozaityte L, Ludwig KU, Birnbaum S, Jagomagi T, et al. Replication of novel susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24 in Estonian and Lithuanian patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2551–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nikopensius T, Kempa I, Ambrozaityte L, Jagomagi T, Saag M, et al. Variation in FGF1, FOXE1, and TIMP2 genes is associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Birth Defects Res A. 2011;91:218–25. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nopoulos P, Berg S, Canady J, Richman L, Van Demark D, Andreasen NC. Abnormal brain morphology in patients with isolated cleft lip, cleft palate, or both: a preliminary analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000;37:441–46. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2000_037_0441_abmipw_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nopoulos P, Berg S, Canady J, Richman L, Van Demark D, Andreasen NC. Structural brain abnormalities in adult males with clefts of the lip and/or palate. Genet Med. 2002;4:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nopoulos P, Berg S, VanDemark D, Richman L, Canady J, Andreasen NC. Increased incidence of a midline brain anomaly in patients with nonsyndromic clefts of the lip and/or palate. J Neuroimaging. 2001;11:418–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2001.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nopoulos P, Langbehn DR, Canady J, Magnotta V, Richman L. Abnormal brain structure in children with isolated clefts of the lip or palate. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:753–58. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pan Y, Ma J, Zhang W, Du Y, Niu Y, et al. IRF6 polymorphisms are associated with nonsyndromic orofacial clefts in a Chinese Han population. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2505–11. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Prescott NJ, Lees MM, Winter RM, Malcolm S. Identification of susceptibility loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in a two stage genome scan of affected sib-pairs. Hum Genet. 2000;106:345–50. doi: 10.1007/s004390051048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rahimov F, Marazita ML, Visel A, Cooper ME, Hitchler MJ, et al. Disruption of an AP-2α binding site in an IRF6 enhancer is associated with cleft lip. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1341–47. doi: 10.1038/ng.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]