Abstract

In order to measure the intermolecular binding forces between two halves (or partners) of naturally split protein splicing elements called inteins, a novel thiol-hydrazide linker was designed and used to orient immobilized antibodies specific for each partner. Activation of the surfaces was achieved in one step allowing direct force measurements of the formation of a peptide bond catalyzed by the binding of the two partners of the split intein (called protein trans-splicing). Through this binding process, a whole functional intein is formed resulting in subsequent splicing. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to directly measure the split intein partner binding at 1µm/s between native (wild-type) and mixed pairs of C- and N-terminal partners of naturally occurring split inteins from three cyanobacteria. Native and mixed pairs exhibit similar binding forces within the error of the measurement technique (~52 pN). Bioinformatic sequence analysis and computational structural analysis discovered a zipper-like contact between the two partners with electrostatic and non-polar attraction between multiple aligned ion pairs and hydrophobic residues. Also, we tested the Jarzynski’s equality and demonstrated, as expected, that non-equilibrium dissipative measurements obtained here gave larger energies of interaction as compared with those for equilibrium. Hence, AFM coupled with our immobilization strategy and computational studies provides a useful analytical tool for the direct measurement of intermolecular association of split inteins and could be extended to any interacting protein pair.

Keywords: Hydrazide, MBP, CBD, Split-inteins, Binding forces, Protein Association

INTRODUCTION

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has been extensively used to investigate structure and function of biological molecules1. AFM is well known for its high resolution imaging capability and it is also a powerful technique for intermolecular force measurements2. Furthermore, the possibility to coat the cantilever tips and substrates with different materials, allows one to study the interaction between different combinations of bound and oriented molecules. Here we have used AFM in force-mode to analyze the interaction between the two binding partners of three naturally split inteins, which are autocatalytic protein splicing elements from diverse cyanobacteria3. Inteins are of both fundamental and biotechnology importance. Some occur in nature in split form and the halves need to associate to function (i.e splice). Here we express three split-intein partners with fused extein tags, which facilitate the immobilization of the different constructs using monoclonal antibodies.

Three main strategies for oriented antibody immobilization were developed over the past 30 years4: (i) Antibodies were bound to Fc receptors on solid supports (e.g. protein A, protein G); (ii) Chemical or enzymatic oxidation of the IgG carbohydrate moiety (mainly in the Fc fragment) into aldehyde groups were reacted with hydrazide activated supports to form covalent hydrazone bonds; (iii) Native thiol-groups, after chemical reduction of the disulfide bonds, were attached to gold or maleimide functionalized surfaces5. The first strategy, while highly specific6, is characterized by non-covalent attachment of the antibody; the third approach, does involve a covalent bound, but could result in inactive antibody fragments due to unintentional reduction of the disulfide bonds7. The second method was selected here, since it also results in covalent antibody attachment but without redox chemistry and it has previously been successfully applied4b, 8. Depending on the substrate, this approach could require several steps in order to activate the surface with hydrazide groups9. Using gold-coated substrates is convenient since the activation can be implemented in one step10. To accomplish this and to orient the molecules correctly, we synthesized a novel thiol-linker with a protected hydrazide moiety.

Since their discovery in 1990, more than 600 inteins have been identified in all three domains of life3b. Splicing (and self-cleaving) of protein elements occurs when an intein catalyzes its self-excision from 2 segments of a protein (exteins) located at its N- and C-termini and simultaneously ligates or reunites the remaining host protein components or exteins. The splicing mechanism has been reviewed11 and extensive engineering of inteins has resulted in many new technologies12. Recent strategies for protein engineering include protein trans-splicing, which is performed by split inteins. Split inteins have not yet been found in eukaryotes but have been identified in diverse cyanobacteria (e.g. C-type DNA polymerase III α subunits, DnaE proteins) and archaea3a, 13. To date, there are around 50 unique sequences of split inteins reported, and the number is rapidly growing as more microbial genomes are sequenced14. Split-intein partners (intein fragment plus the neighboring extein sequence) are generally inactive until they associate and initiate splicing activity15. The association between two split-intein partners is not a ligand-protein interaction but the reconstruction of a protein fold, which restores intein splicing activity. Here we study three split inteins from diverse cyanobacteria: Oscillatoria limnetica (Oli), Thermosynechococcus vulcanus (Tvu) and Nostoc species PCC7120 (Nsp).

Despite the many applications and studies on splicing kinetics11h, 15a, 16, very little is known about the molecular recognition events preceding the protein trans-splicing process. Contreras Martinez and co-workers17 identified the hydrophobic core amino acids between the two protein fragments that were crucial for split-protein reassembly. Shi and Muir18 presented the first thermodynamic and kinetic analysis of only the binding event between split-intein partners, independently of the splicing reaction. Using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), they showed that the naturally split intein, Synechocytis sp. (Ssp) DnaE partners bound with low nanomolar affinity (Kd = 43±10 nM), resulting from very fast association rates (kon = 2.8±0.5 107 M−1 s−1) and moderately slow dissociation rates (koff = 1.2±0.2 s−1). Also, the kinetic constants depended on ionic strength of the buffer, suggesting a contribution by electrostatic interactions between split-intein partners. Later Ludwig and co-workers monitored the association of artificially split-intein partners from a mutant Ssp DnaB intein, which blocked protein splicing, by native PAGE and fluorescence anisotropy19. The kinetic parameters for intein complex formation were Kd = 1.1 µM, kon = 16.8 M−1 s−1, and koff = 1.8*10−5 s−1. The authors suggest that the very low kon value for this artificial intein fragment association likely reflects required major structural changes (the split fragments are largely unfolded), compared with the Ssp DnaE fragments which have undergone natural evolution for efficient protein trans-splicing. Consideration of association of split inteins would clearly benefit from direct experimental measurements.

For direct measurement of the interactions (forces and energies) between split intein partners, a novel thiol-hydrazide linker was designed and used to orient immobilized antibodies specific for each intein partner. The binding force measurements performed here shows that native (from same species) and mixed (from different species) split-intein pairs exhibit similar binding energies within the error of the measurement technique. This finding is in concert with Dassa and co-workers results3a, which showed that all nine combinations of the same split-intein partners can induce protein-splicing and have suggested that split inteins, sharing 50–70% of sequence identity, derive from a common progenitor13a. Molecular details from our bioinformatic sequence analysis of the binding surface demonstrate interdigitated electrostatic and non-polar attraction of aligned ionic and hydrophobic amino acid pairs, explaining how the intein binding partners are guided toward each other for subsequent binding. Thus, our novel immobilization procedure, AFM-force spectroscopy and bioinformatic sequence analysis with computational structural prediction provide a direct analytical tool to investigate the association of split splicing-proteins. These approaches give a fundamental understanding of molecular recognition in trans-splicing, while they will facilitate the design of artificial split inteins for practical uses, and they offer a direct way of measuring binding between any proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Linker

A linker was synthesized for direct and oriented immobilization of antibodies on gold surfaces. The linker had two reactive end groups: thiol and hydrazide. Thiol groups react directly with gold; the hydrazide group can be covalently coupled to carbohydrate residues in glycoproteins and other glycoconjugates after oxidation to produce aldehydes20. The disulfide structure and protective hydrazide were important for the synthesis of the linker, rather than the immobilization strategy. Details of the linker synthesis are presented in Supporting Information (Figure S1).

Antibodies

Anti-MBP and anti-CBD monoclonal antibodies were used for protein immobilization (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) and HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA) were utilized in an ELISA assay, as coating and secondary antibody, respectively. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies were used for luminol-based detection in Western blots (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Proteins

Three naturally occurring split inteins were chosen from diverse cyanobacteria: Oscillaria limnetica, Thermosynechococcus vulcanus and Nostoc species PCC7120. Each N-terminal intein domain (IN) was cloned downstream to a maltose-binding domain (MBP) and each C-terminal intein domain (IC) was cloned between an upstream MBP to enhance its solubility, and a downstream chitin-binding domain (CBD). The fusion proteins were identical to those studied by Dassa et al.3a. MBP-CBD protein was also expressed as a negative control. IN, IC and MBP-CBD were purified using their affinity MBP tags. Details are in Supplementary Information (Figures S2, S3 and S4). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was certified ACS reagent grade (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Chemicals and solutions

The oxidant used to obtain aldehydes groups in anti-MBP and anti-CBD antibodies before immobilization was NaIO4 (98–100%) (Thermo Scientific - Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). NaCl was certified ACS (FisherScientific, Pittsburgh, PA). All the other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO: EDTA (≥ 98.5%, cell culture tested), Na azide (99.5%), NaH2PO4 (Reagent plus, ≥ 99%), Na2HPO4 (Reagent plus, ≥ 99%), TFA (99% solution), tetrahydrofuran (THF) (99.9% solution), Tris-HCl (minimum 99% titration, performance certified), HCl (37% solution) and ethanol (99.5% solution) were ACS reagent grade. Buffers were filtered prior to use through a 0.22 µm poly(ether sulfone) membrane filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA).

Chemical modification of the substrates

The immobilization of split-intein partners onto gold-coated cover slips and AFM cantilevers (Novascan, Ames, IA) followed a 4-step protocol, which exploited the high affinity of the antibodies for the proteins fused domains (Scheme 1).

Preparation and cleaning of the substrates. Gold-coated surfaces were prepared by deposition onto glass cover slips of a first layer of 15 nm of titanium (99.999% International Advanced Materials) and a second layer of 50 nm of gold (99.999% International Advanced Materials), using an electron beam evaporator21. The gold coated surfaces and the AFM probes (tips), supplied with an immobilized 10 µm diameter gold-coated borosilicate glass sphere, were washed with ethanol before chemical modification.

Linker immobilization. Cover slips and AFM probes were immersed in a 2 mM protected disulfide-hydrazide linker solution in ethanol, at 20°C for 24 h, and then thoroughly washed with THF. Before the antibody immobilization, the linker had to be de-protected. To do that, the cover-slips were immersed in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), at 20°C for 1 h, and then thoroughly washed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) pH 7.0.

Anti-MBP and anti-CBD antibodies immobilization. In order to functionalize the antibodies with the linker, the glycosylated groups at the Fc region of the antibodies were oxidized, so that the resultant cis-diols were transformed into reactive aldehyde moieties. These aldehydes then were combined with the exposed hydrazide groups of the linker to form stable, leak-resistant hydrazone linkages, so both the antigen-binding sites were free to interact with the antigen in the final step. The oxidation was performed in an amber vial, as the reaction was light sensitive, dissolving 1.5 mg NaIO4 with 400 µl of phosphate buffer (PB). Then 2 µl of anti-MBP or anti-CBD were added, gently mixed and incubated for 30 min at 20°C. Purification was unnecessary, as only oxidized antibodies could bind and any non-oxidized antibodies were washed away during the binding to the substrates. The oxidized antibodies were then directly added to the reactive substrates in order to bind the available primary amine groups, and incubated at 20°C for 1 h. Afterwards, the substrates were thoroughly washed with 20 mM Tris HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na azide, pH 7.4 (intein buffer, IB).

Split-intein immobilization. The reactive substrates were finally incubated with a split-intein solution, obtained from the purification step, at 20°C for 1 h. The samples were then thoroughly washed with IB.

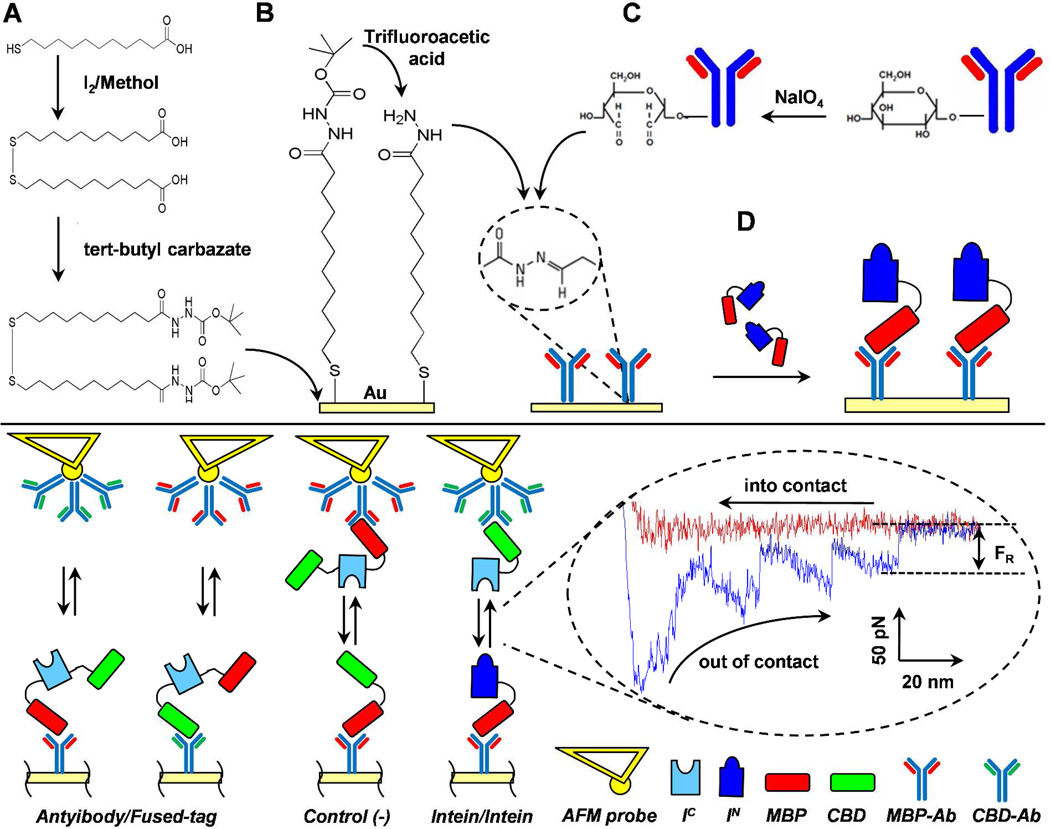

Scheme 1.

Experimental design. (Top) Chemistry cartoon of the immobilization of split inteins on gold-coated substrates: (A) linker synthesis; (B) immobilization of the disulfide hydrazide linker and its deprotection using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA); (C) immobilization of the antibodies, after oxidation of glycosylated groups at the Fc region; (D) immobilization of split-intein partners. (Bottom) Cartoon of the AFM experimental set up: Control (antibody/fused-tag) experiments, for measuring the interaction between the antibodies and the tagged domains of the split-intein partners, CBD and MBP; negative control, using a non-interacting protein, MBP-CBD in this case; and intein/intein interaction measurement, for measuring the association between the two split proteins. In the dashed circle, a typical AFM force-distance curve between split-intein partners, where the approach (into contact) and the separation (out of contact) curves are shown. The rupture force FR is shown as the last force during separation. IC and IN are the C- and N-terminal intein domain, respectively; MBP, maltose-binding domain; CBD, chitin-binding domain; anti-MBP and anti-CBD monoclonal antibodies against the fused domains MBP and CBD, respectively.

Detection of immobilized antibodies

An ELISA assay was designed to check the anti-MBP and anti-CBD antibodies on gold coated substrates, before intein partner immobilization. The ELISA assay was first optimized to detect the antibodies in solution. Details are given in the Supporting Information (Figure S5). The assay was then adjusted to detect the antibodies immobilized on the gold-coated surfaces. The modified substrate was placed into an empty well of a 96-well plate and the ELISA assay was performed on the samples adding the HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG, the substrate 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine and finally the stop reagent. The solution was then transferred into a new well for absorbance reading at 450 nm.

Force measurements

Atomic force microscopy in force mode was used to measure the interactions between native and mixed pairs of split inteins. The adhesion force (Fad) was defined as the maximum adhesive force observed on retraction of the sample away from the tip21. Technically, Fad measures an “unbinding” event. Binding between split-intein partners and subsequent splicing (unbinding) of the whole intein are the two steps of biological interest. We focus here on the first step and thus we refer to Fad as a “binding force” rather than an “unbinding force” which would be misleading due to the second step. The average Fad was calculated from a set of 400 data-points for each run. All measurements were taken at an approach speed of 0.6 µm/s and with a dwell time toward the surface of 0.99 s. For imaging with AFM, high resolution topographic images are usually achieved using sharp tips, but for force measurements the mechanical properties of the AFM probe or tip become critical. Also tips with spherical (used here) or paraboloid shapes generate conditions of lowest stresses and strains compared with other profiles, including the pyramidal profile of the most common AFM silicon nitride tips22. For each experiment the spring constant was estimated using a standard 3-steps procedure: (i) determine the virtual deflection in optical path; (ii) determine the slope of the contact region from a deflection-distance curve to determine the “inverse optical lever sensitivity” of the cantilever (in nm/V); (iii) withdraw tip and perform a thermal tune to determine the cantilever’s resonant frequency. The spring constants were 65.88, 51.38 and 38.67 pN/nm for Nsp, Oli and Tvu modified tips, respectively (the cantilever spring constant supplied by the manufacturer was 60 pN/nm). A typical force-distance curve between split-intein partners is shown in Scheme 1. The presence of multiple-peaks during retraction is a fingerprint of the interaction between multiple domains, while the first peak on the left is due to nonspecific interaction between tip and substrate and the farthest peak to the right is the rupture force between the last single molecule interacting across the gap23.

Equipment

An electron beam evaporator was used to deposit gold onto the substrate (Temescal BJD-1800, BOC Edwards, UK). The force measurements were performed using an atomic force microscope (MFP-3DTM system, Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA). The data were collected and analyzed using commercial software (IGOR Pro 5, WaveMetrics, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR).

THEORETICAL SECTION

Analysis of non-equilibrium and equilibrium binding energies

In order to explicitly compare our non-equilibrium measured binding energies to the equilibrium binding energies of the natural Ssp DnaE intein partners (Kd = 43±10 nM) of Shi and Muir18, we invoke and use the Jarzynski equality relating irreversible work, Δwi, to the equilibrium free energy difference, ΔG24. Repeating each force (binding) measurement, Fi(x), i = N times, we obtain the mean work needed to pull the force from position, x1, to position x2, as:

| (1) |

In general ΔG ≤ Δwi, and their difference is the dissipative work. The Jarzynski equality states that when the average taken over an infinite number of trials (far from the equilibrium) is Boltzmann (KB) and temperature (T) - weighted according to the work required for each repetition, the result will always be the free energy difference, ΔG:

| (2) |

Here, we compare equilibrium free energy difference measurements, ΔG, estimated from the literature with our dissipative work, Δwi, from direct force measurements.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

First, evidence is provided that the antibodies are oriented and immobilized covalently on the gold surface correctly. Next, results of direct force measurements between (i) antibodies with fused tags (70–90 pN), (ii) split-intein partners (50–52 pN) and (iii) negative controls (< 30 pN) are presented below. Then, analyses of a comparison of non-equilibrium with equilibrium binding energies and of the molecular structures and sequences at the binding interfaces of the split inteins are presented. Finally, we provide a molecular rationale for similar binding forces among split-intein partners with a bioinformatic analysis that points to a zipper-like interface involving charged and apolar residues.

Evidence of covalent immobilization of antibody via ELISA

The AFM sample preparation requires the covalent immobilization of antibodies on gold coated substrates. In order to verify this arrangement, these surfaces were placed in a 96-well plate for an ELISA assay that was designed for this task. Two controls were included: (i) an empty well, and (ii) a gold coated substrate, after linker immobilization. The empty well was necessary to estimate the nonspecific binding of the HRP-linked antibody, while the gold-coated substrate gave the interaction between the HRP-linked antibody with the substrate (gold and linker) before anti-MBP or anti-CBD antibody immobilization. Results, confirming the detection of immobilized antibodies, are summarized in Table 1. As expected, the background signals, both from the empty well and the substrate (controls), were small compared with those for the modified substrates. Using the calibration curves established for antibodies in solution (Figure S5), it was possible to estimate “equivalent concentrations” of bound antibodies of ~30 ng/ml and ~20 ng/ml from the A450 values of 1.222 and 0.633 for anti-MBP and ant-CBD, respectively. Although we could not translate these values to a surface density, the aim here was to confirm the presence of antibodies on the gold coated substrates (cover slip and AFM cantilever) and, hence, validate part of the modification protocol.

Table 1.

ELISA assay of substrates: A450a of controls and samples after antibody immobilization.

| Sample | A450a |

|---|---|

| Empty wellb (control) | 0.062 |

| Gold + linkerc (control) | 0.061 |

| Gold + linker + anti-MBP antibody | 1.222 |

| Gold + linker + anti-CBD antibody | 0.633 |

Absorbance reading at 450 nm.

Polysterene microtiter plate.

Disulfide hydrazide.

Direct Force measurements

Antibody-fused tag interactions

In order to measure the molecular interactions between native and mixed pairs of split-intein partners, we first confirmed that the molecular constructs for each surface were present and that the weakest link among these connecting supports was between the pairs of split inteins and not elsewhere (Scheme 1). The disulfide organic links, attached to gold, and the hydrazide links, attached to the oxidized carbohydrate groups on the Fc region of the antibodies, were covalent in nature and therefore could not have released prior to the non-covalent pair interactions of the split inteins25. The only other possible weak link was between the variable region of the monoclonal antibodies and the tagged domains (MBP and CBD) attached as pendants to the split-intein pairs. To test these interactions, we measured their binding energies directly using intein C-domain, IC, from all three species, which were cloned with both MBP and CBD. Hence, to measure the interaction between CBD and the anti-CBD antibody, we immobilized the anti-CBD antibody on the cantilever probe and the IC construct on a substrate using MBP and anti-MBP antibody; we swapped the antibodies to measure the interaction between MBP and anti-MBP (Scheme 1). The analysis of the multiple peaks is summarized in Figure 1, where the distribution of the interaction forces is reported for the three inteins and the two antibodies. The resulting distributions exhibited lognormal behavior and were very similar among the three proteins, for the same antibody. Hence, it was possible to stack each of the three distributions for the different proteins and the same antibody, resulting in a “global” distribution with an expected value of 70 [4.39±0.38]** pN and 90 [4.59±0.29] pN for anti-MBP and anti-CBD antibodies, respectively. These values were in good agreement with those reported in the literature for similar experiments between antigens and IgG antibodies, ranging from 60 to 244 pN26. While ELISA only proved the covalent attachment of the antibodies, but not their orientation (e.g. some antibodies may lie down on the surface), the reproducibility of these results with force values in the expected range confirms the covalent and oriented immobilization of antibodies. This clearly would not be observed with non-specific binding. This confirms that the antibody variable regions are exposed and interact with their antigens, i.e. MBP and CBD which are attached as pendants to the split-inteins pairs and hence guarantee their immobilization in the last step of the modification protocol.

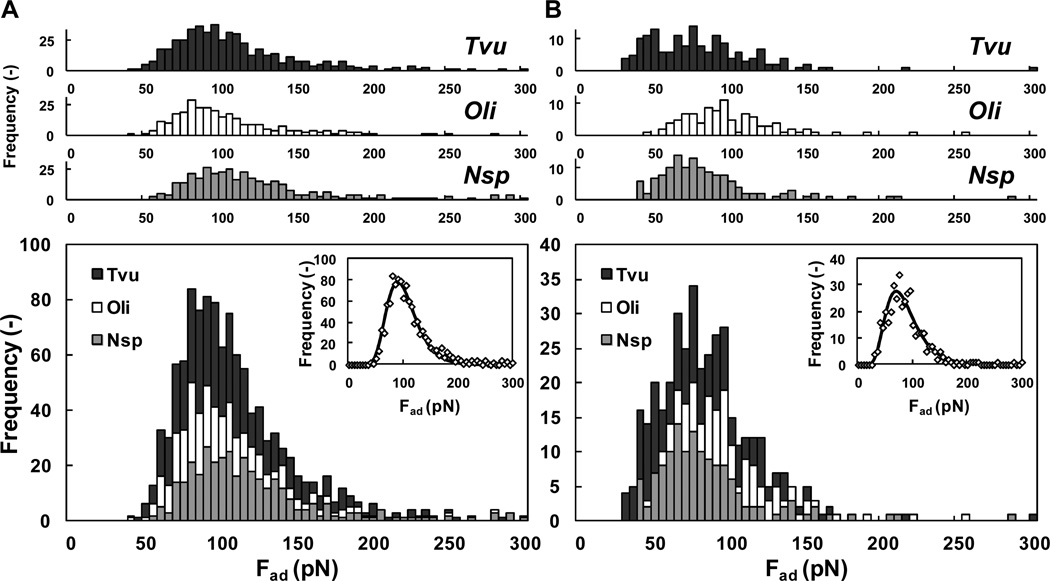

Figure 1.

Antibody/fused-tag experiments. Measurements of AFM binding forces for: (A) CBD versus anti-CBD antibody and (B) MBP versus anti-MBP antibody. These experiments were performed using IC (with both fused domains CBD and MBP, according to Scheme 1) with all 3 species: Nsp, Oli and Tvu (top histograms). The results are stacked together (bottom histogram) and fitted with a lognormal distribution (insert): For CBD µ = 4.59 and σ = 0.29, while for MBP µ = 4.39 and σ = 0.38. Each run was repeated 400 times for all combinations.

Split-inteins interactions

The substrates and cantilever tips were modified with the IC and IN partners, respectively (Scheme 1). In particular, the MBP domain that was originally in the IC fragment together with a CBD tag, was removed during protein purification to avoid cross-interaction between the MBP tag and the anti-MBP antibody immobilized on the substrate and holding the IN fragment. The cleaved CBD-IC (11 kDa) was immobilized on the cantilever tip, while the MBP-IN (55 kDa) was immobilized on the substrate (gold-coated cover slips and AFM cantilevers). Split inteins from three cyanobacteria, Tvu, Nsp and Oli gave 9 possible combinations: 3 native (partners from the same species) and 6 mixed (partners from different species). Single force-distance curves were similar in profile to the antibody/fused tag experiments, showing multiple peaks for each run (Figure 2 including Table 2). Statistical analysis for all the data showed an indistinguishable difference in intermolecular forces between native and mixed pairs. A force of ~52 [4.17±0.47] pN was measured for all 9 combinations. The lognormal profiles, for both the antibody/fused tag and the split-intein experiments, could be interpreted as the result of multiple pair interactions. Thus, the data can be fitted with multiple Gaussian curves, with multiple mean values: 1 μ, 2 μ, 3 μ and so on. A similar force value (50.8±15.8 pN, for the first peak) to the lognormal analysis (~52 pN) was obtained by fitting the data with three Gaussian curves, i.e. deconvoluting larger interaction forces into components that represent multiple simultaneously interacting split-intein pairs. Details of this alternative analysis are also presented in Figure 2.

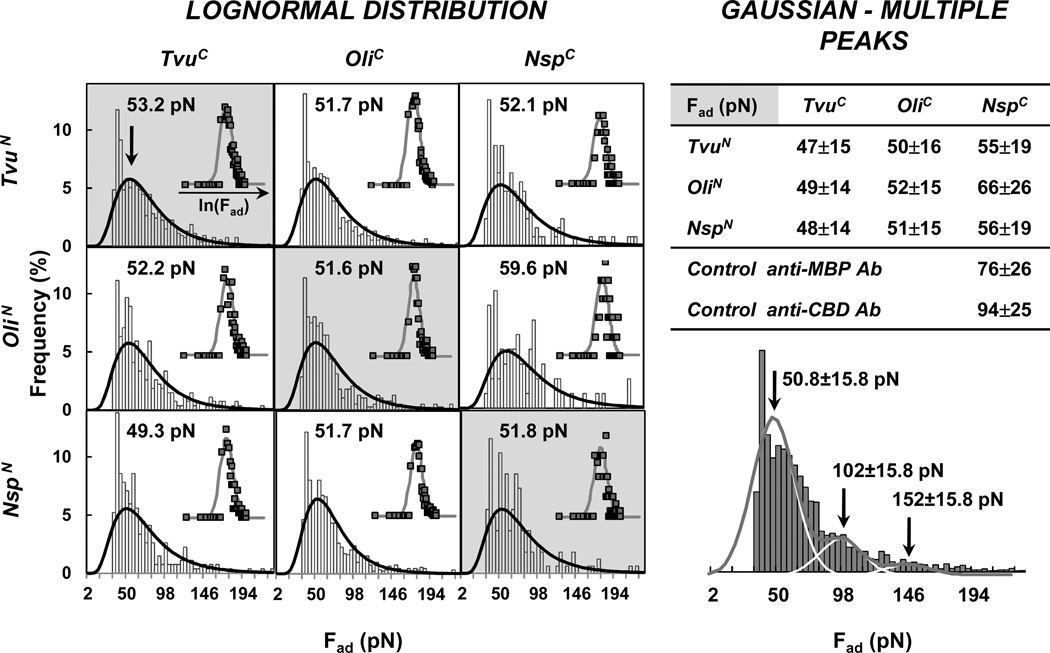

Figure 2.

Intein/intein experiments. Measurements of AFM binding forces for all 9 combinations of split-intein pairs: IN from all 3 split inteins Tvu, Oli and Nsp were combined with all IC according to Scheme 1. (Left) Lognormal analysis for the 3 native (grey background, diagonal) and 6 mixed (white background, off diagonal) pairs. The inserts represent the normal distributions of the variable’s natural logarithm (blue square) and their fitting (red line). (Right) Multiple Gaussian peaks analysis. The table summarizes the interaction forces for the individual pair in terms of mean, µ, ± the standard deviation, σ. The histogram represents the combined AFM intermolecular forces for all 9 split-intein pairs, fitted (red line) using multiple (3) Gaussian curves (white lines). Each run was repeated 400 times for all combinations.

Table 2.

Interaction forces between immobilized split-intein partners.

| Fad (pN) |

TvuC | OliC | NspC |

|---|---|---|---|

| TvuN | 53 [4.19±0.47] |

52 [4.17±0.48] |

52 [4.22±0.51] |

| OliN | 52 [4.18±0.48] |

52 [4.17±0.48] |

60 [4.33±0.49] |

| NspN | 49 [4.16±0.51] |

52 [4.14±0.44] |

52 [4.19±0.50] |

Tvu, Oli and Nsp denote the 3 cyanobacteria, O. limnetica, T. vulcanus and Nostoc species PCC7120, respectively. C- and N- denote the IC and IN components.

The antibody-fused tag interaction forces of 70 pN for MBP and 90 pN for CBD, were statistically higher (35 and 73%, respectively) than 50–52 pN, measured for split-intein partners. Thus, the possibility of rupturing the antibody-fused tag bond, which was the same for all experiments, was eliminated. Other forces in the constructs were covalent in nature.

The hypothesis that the splicing reaction occurred during the force measurements was also rejected. Previous studies of DnaE trans-splicing suggest that association of the split-intein fragments is rapid relative to the subsequent splicing reaction, which occurs in minutes to hours16c, 18. In particular, for Oli, Tvu and Nsp, 30 min is the minimal time at room temperature to clearly observe splicing products on SDS-PAGE3a, while each single AFM run was performed over a few seconds with a dwell time of 1 s. Also, if splicing and extein ligation had taken place during the force measurements, forces of the order of 70 pN and 90 pN for antibody-fused tag interactions or forces <50–52 pN between antibodies would have been observed. Neither of these forces was recorded. Thus, splicing was not likely during the AFM measurements based on time scales or force observations.

Negative control

To validate the results and the specific interactions between split-intein partners, the MBP-CBD construct was expressed, purified and used as a negative control. Since it is lacking a split-intein domain, the construct is expected to be non-interacting toward both MBP-IC-CBD and MBP-IN. MBP-CBD and MBP-IC-CBD were immobilized on the substrate and on the cantilever tip, respectively, and the AFM force experiment was repeated for all three IC proteins, Tvu, Nsp and Oli (Scheme 1). Results are summarized in Figure S6A and they show that a majority of interactions (over 90%, for Nsp and Oli, and 73%, for Tvu) was well below 50 pN. In addition, the histogram plots (Figure S6A) highlight events that showed either no interaction at all or forces below 30 pN, which was chosen as the minimum value of measurable force. An example of raw data is also reported in Supporting Information (Figure S6B).

Comparison of non-equilibrium with equilibrium binding energies

We wish to compare equilibrium with non-equilibrium binding energies (Figure S7). The dissociation constant Kd = 43±10 nM calculated by Shi and Muir18 was used to estimate the free energy, ΔG = −RTln(Kd) = 21.4 KBT. The distribution of Δwi measurements was used to estimate the average non-equilibrium work, <Δw> = 197±97 KBT (Figure S7). The results indicate that ΔG<<Δw> and ΔG and <Δw> are of the same order of magnitude (21.4 KBT and 197±97 KBT, respectively). Since only a finite number of work trajectories were measured here (N~113) this result is expected27. These results validate their similar binding energies and hence the reasonableness of their values.

Molecular structures and sequences at the binding interfaces

To probe a molecular rationale for similar binding forces among the different interacting split-intein partners, a bioinformatic sequence analysis was performed. A sequence Logo alignment of Oli, Tvu and Nsp (Figure 3) was examined in relationship to opposing residues in the two halves of the split inteins as modeled using the Phyre2 program28. This analysis shows how many of the highly conserved charged amino acids are found to be (i) clustered in the two long strands comprising most of the contact area between the IN and IC split-intein parts and (ii) participating in intermolecular ion pairs (e.g. Glu85-Arg123) and ion triads (e.g. His48-Asp133-His72 and Glu93-Lys119-Glu61). These two long “contact strands” display three additional non-polar patches comprising hydrophobic residues interspersed between each ion pair previously listed: Pro43/Ile44/Ala45/Trp47-Ile134/Leu136, Val55-Val126/Trp128/Val131 and Leu60-Ile120/Val121. The conservation of these interdigitated electrostatic and non-polar interactions provides a molecular explanation for the similar forces measured among the different split-intein pairs described above.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the molecular interfaces of the split-inteins pairs. (Top) Sequence Logo based on the segment alignment of Nsp, Oli and Tvu, for both IN (above) and IC (below), highlighting the highly conserved charged (left, basic in blue and acidic in red) and non-polar (right, black) residues. (Bottom) The structure of the complete molecule Tvu (middle) was determined using Phyre228: IN, residues 1–118 (orange), and IC, residues 119–152 (green). Selected portions of the molecule highlight the intermolecular electrostatic (left) and non-polar (right) interactions between IN, residues 43–62 (orange) and IC, residues 119–136 (green). The red and blue outlines (left) identify acidic and basic patches, respectively. Interacting residues are shown in the different boxes.

Shi and Muir18 and Dassa and co-workers3a have postulated the role of ionic interactions in split-intein assembly. In their work, Dassa et al.3a showed that all 9 combinations of the same split-intein partners studied here can induce protein-splicing despite a 30–50% sequence variation between native split inteins, whether the split-intein halves had opposite charges or when both halves were negative. Similar results were found here in terms of binding forces between, for example, OliN (−10.0) with NspC (+2.8) (opposite charges; ΔCharge ~ |12.8|) or with OliC (−0.2) (both negative; ΔCharge ~ |9.8|). While previously postulated, Shah et al.11f have recently investigated the role of specific ionic interactions for fragment assembly and splicing for the Nostoc punctiforme split intein, both in vivo and in vitro. The authors found that charge complementation or repulsion could bias relative split-intein binding affinities, which in turn could affect relative splicing kinetics. However, the magnitude of these energetic effects did not fully explain the splicing selectivity observed in vivo. Knowing the importance of electrostatic29 and non-polar30 attractions in binding, the multiple interdigitated highly conserved ion and non-polar pairs seem to form a complementary components of a zipper which could explain the indistinguishable intermolecular forces between native and mixed pairs measured with AFM. We have repeated the same bioinformatics (sequence Logo) analysis described above with the 13 naturally occurring split inteins (including the original three: Tvu, Nsp and Oli) reported by Dassa et al.3a. Both the analysis of the three split inteins and the 13 inteins (ours plus 10 more inteins) for the C- and N-termini are included in the Supporting Information (Figure S8). It is impressive to see how the same conserved amino acids are present in all 13 split inteins for both the charged amino acids and the non-polar amino acids. These results strongly support and generalize our findings ("zipper-like interface") and are in concert with the splicing results of Dassa and co-workers3a, suggesting that not only splicing activity, but also fragment association could be the result of local (rather than global) charge distributions between split-intein halves. Given similar interactions between split-intein partners, we speculate that, in spite of 30–50% sequence variation between the constructs, they originated from the same progenitor and diverged while maintaining key electrostatic and non-polar interactions required for association.

One could potentially use this same assay to explore additional fundamental questions on split intein recognition, e.g. one could mutate the highly conserved amino acids along the zipper-like interface, and investigate the importance of both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions., This immobilization method could also be adopted to intein technologies. For example one could design immobilized split inteins arrays and use them to screen for binding partners by AFM.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the molecular details of binding between split-intein partners before trans-splicing are lacking, the goal of this research was to directly measure the intermolecular interactions between the various partners of three split intein species, Oli, Tvu and Nsp, using AFM in force mode. To accomplish this, we synthesized a novel thiol-hydrazide-linker that permitted single-step covalent and oriented immobilization of fusion-tag antibodies (anti-MBP and anti-CBD) onto opposing gold surfaces. The split-intein fragments, IN and IC, were then immobilized via their fusion tags (MBP and CBD), leaving them free to interact with their partner. All 9 pairs – native and mixed – exhibited similar binding forces (~50–52 pN), which were statistically higher than the negative controls of 30 pN, and below 70–90 pN, for the antibody-fused tag interactions.

The main conclusions are that: (i) Split inteins from different species of Cyanobacter had similar binding energies, (ii) both electrostatic and non-polar attraction of aligned ionic and hydrophobic pairs guided partner binding between native and mixed split-intein pairs for all three inteins in a zipper-like fashion (10 other split inteins exhibit the same zipper-like structure at their binding surface), (iii) a new linker was synthesized that is generally useful for oriented covalent immobilization of antibodies on gold for measuring intermolecular forces between proteins or other molecular pairs, and (iv) as required, non-equilibrium dissipative measurements gave larger energies of interaction as compared with those for equilibrium but values of similar order.

Although previous researchers3a, 11f, 18 have proposed that electrostatic interactions play a role in split-intein binding, none have suggested that both electrostatic and hydrophobic amino acids are important in such binding and that these interactions are interspersed and aligned along a zipper-like binding interface. That these interspersed polar and non-polar amino acids on both strands have very high homology across the three species of Cyanobacteria provides a molecular explanation why split inteins from different species have similar binding energy. The similar avidity is evolutionarily important and relevant to biotechnology and biomedicine.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John T Dansereau, (Wadsworth Center, Albany, NY) Carol L Piazza, Dorie Smith, Brian P Callahan and Natalia I Topilina (SUNY, Albany, NY) for help with cell growth, polyacrylamide gels, Western blots and bioinformatic sequence analysis; Bob Linhardt (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY) for suggesting the use of antibodies for the oriented immobilization of the split inteins; Gil Amitai (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) for discussions on split-intein results; Amish Patel and Shekhar Garde (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY) for discussion on the Jarzynski equality; and Ryan Fuierer (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) for help in analyzing the AFM force runs.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, via DOE grants DE-FG02-90ER14114 and DE-FG02-05ER46249 to GB, the US National Science Foundation via NSF-NIRT grants CTS-0304055 and CBET-1122780 to GB, and the National Institutes of Health via NIH grant GM44844 to MB.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Oli

Oscillatoria limnetica

- Tvu

Thermosynechococcus vulcanus

- Nsp

Nostoc species PCC7120

- MBP

maltose binding domain

- CBD

chitin binding domain

- IN

N-terminal intein domain

- IC

C-terminal intein domain

- TFA

trifluoracetic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- PB

phosphate buffer

- IB

intein buffer

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- Fad

adhesion force

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Additional information as noted in text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MS, MB and GB. Performed all experiments and analyzed the data: MS. Provided IC and IN clones: BD and SP. Synthesized the linker: HL. Helped setting up AFM runs: GA and AKD. Wrote the paper: MS, MB and GB.

We report the mode, point of global maximum of the probability density function of log-normal distributed values, defined as exp(µ – σ2), and in parenthesis the mean, µ, ± the standard deviation, σ, of the variable’s natural logarithm.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.(a) Bowen WR, Lovitt RW, Wright CJ. Biotechnol Lett. 2000;22:893–903. [Google Scholar]; (b) Horber JK, Miles MJ. Science. 2003;302:1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1067410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hugel T, Seitz M. Macromol Rapid Comm. 2001;22:989–1016. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang J. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2004;41:435–449. doi: 10.1385/CBB:41:3:435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butt HJ, Cappella B, Kappl M. Surf Sci Rep. 2005;59:1–152. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Dassa B, Amitai G, Caspi J, Schueler-Furman O, Pietrokovski S. Biochemistry. 2007;46:322–330. doi: 10.1021/bi0611762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perler FB. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:383–384. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Gersten DM, Marchalonis JJ. J Immunol Methods. 1978;24:305–309. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(78)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoffman WL, Oshannessy DJ. J Immunol Methods. 1988;112:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) O'Shannessy DJ, Hoffman WL. Biotechnology and applied biochemistry. 1987;9:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-8744.1987.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) O'Shannessy DJ, Quarles RH. Journal of applied biochemistry. 1985;7:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Werner S, Machleidt W. Eur J Biochem. 1978;90:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu B, Smyth MR, O'Kennedy R. The Analyst. 1996;121:29R–32R. doi: 10.1039/an996210029r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song HY, Zhou X, Hobley J, Su X. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2012;28:997–1004. doi: 10.1021/la202734f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alves NJ, Kiziltepe T, Bilgicer B. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2012;28:9640–9648. doi: 10.1021/la301887s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Brne P, Lim YP, Podgornik A, Barut M, Pihlar B, Strancar A. Journal of chromatography. A. 2009;1216:2658–2663. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Han HJ, Kannan RM, Wang SX, Mao GZ, Kusanovic JP, Romero R. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:409–421. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200901293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hong SR, Choi SJ, Jeong HD, Hong S. Biosensors & bioelectronics. 2009;24:1635–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Qian WP, Xu B, Wu L, Wang CX, Yao DF, Yu F, Yuan CW, Wei Y. Journal of colloid and interface science. 1999;214:16–19. [Google Scholar]; (e) Shmanai VV, Nikolayeva TA, Vinokurova LG, Litoshka AA. BMC biotechnology. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zara JJ, Wood RD, Boon P, Kim CH, Pomato N, Bredehorst R, Vogel CW. Analytical biochemistry. 1991;194:156–162. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90163-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gering JP, Quaroni L, Chumanov G. Journal of colloid and interface science. 2002;252:50–56. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2002.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Kang JH, Choi HJ, Hwang SY, Han SH, Jeon JY, Lee EK. Journal of chromatography. A. 2007;1161:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mallidi S, Yantsen E, Larson T, Sokolov K, Emelianov S. P Soc Photo-Opt Ins. 2008;6856:85616–85616. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Amitai G, Callahan BP, Stanger MJ, Belfort G, Belfort M. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11005–11010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904366106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans TC, Jr, Xu MQ, Pradhan S. Annual review of plant biology. 2005;56:375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Noren CJ, Wang JM, Perler FB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2000;39:450–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Paulus H. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:447–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pereira B, Shemella PT, Amitai G, Belfort G, Nayak SK, Belfort M. Journal of molecular biology. 2011;406:430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Shah NH, Vila-Perello M, Muir TW. Angewandte Chemie. 2011;50:6511–6515. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Shemella PT, Topilina NI, Soga I, Pereira B, Belfort G, Belfort M, Nayak SK. Biophys J. 2011;100:2217–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Xu MQ, Perler FB. Embo J. 1996;15:5146–5153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Cheriyan M, Perler FB. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2009;61:899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chong SR, Mersha FB, Comb DG, Scott ME, Landry D, Vence LM, Perler FB, Benner J, Kucera RB, Hirvonen CA, Pelletier JJ, Paulus H, Xu MQ. Gene. 1997;192:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mootz HD. Chembiochem: a European journal of chemical biology. 2009;10:2579–2589. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Caspi J, Amitai G, Belenkiy O, Pietrokovski S. Molecular Microbiology. 2003;50:1569–1577. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Choi JJ, Nam KH, Min B, Kim SJ, Soll D, Kwon ST. Journal of molecular biology. 2006;356:1093–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Iwai H, Zuger S, Jin J, Tam PH. FEBS letters. 2006;580:1853–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu XQ, Yang J. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:26315–26318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wu H, Hu ZM, Liu XQ. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah NH, Muir TW. Israel Journal of Chemistry. 2011;51:854–861. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201100094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Brenzel S, Kurpiers T, Mootz HD. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1571–1578. doi: 10.1021/bi051697+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mills KV, Lew BM, Jiang SQ, Paulus H. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3543–3548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Volkmann G, Sun WC, Liu XQ. Protein Sci. 2009;18:2393–2402. doi: 10.1002/pro.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wu H, Xu MQ, Liu XQ. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1998;1387:422–432. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Al-Ali H, Ragan TJ, Gao XX, Harris TK. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1294–1302. doi: 10.1021/bc070055r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lew BM, Mills KV, Paulus H. Biopolymers. 1999;51:355–362. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1999)51:5<355::AID-BIP5>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martin DD, Xu MQ, Evans TC. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1393–1402. doi: 10.1021/bi001786g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mills KV, Manning JS, Garcia AM, Wuerdeman LA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:20685–20691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Nichols NM, Benner JS, Martin DD, Evans TC. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5301–5311. doi: 10.1021/bi020679e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zettler J, Schutz V, Mootz HD. FEBS letters. 2009;583:909–914. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez LMC, Quintana EEB, Escobedo FA, DeLisa MP. Biophys J. 2008;94:1575–1588. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi J, Muir TW. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6198–6206. doi: 10.1021/ja042287w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig C, Schwarzer D, Mootz HD. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:25264–25272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Shannessy DJ, Wilchek M. Analytical biochemistry. 1990;191:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90377-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sethuraman A, Han M, Kane RS, Belfort G. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2004;20:7779–7788. doi: 10.1021/la049454q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimitriadis EK, Horkay F, Maresca J, Kachar B, Chadwick RS. Biophys J. 2002;82:2798–2810. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Fisher TE, Marszalek PE, Fernandez JM. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:719–724. doi: 10.1038/78936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee G, Abdi K, Jiang Y, Michaely P, Bennett V, Marszalek PE. Nature. 2006;440:246–249. doi: 10.1038/nature04437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Crooks GE. J Stat Phys. 1998;90:1481–1487. [Google Scholar]; (b) Crooks GE. Phys Rev E. 1999;60:2721–2726. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jarzynski C. Phys Rev E. 1997;56:5018–5035. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jarzynski C. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;78:2690–2693. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandbois M, Beyer M, Rief M, Clausen-Schaumann H, Gaub HE. Science. 1999;283:1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Dammer U, Hegner M, Anselmetti D, Wagner P, Dreier M, Huber W, Guntherodt HJ. Biophys J. 1996;70:2437–2441. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79814-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hinterdorfer P, Baumgartner W, Gruber HJ, Schilcher K, Schindler H. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3477–3481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stuart JK, Hlady V. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 1995;11:1368–1374. doi: 10.1021/la00004a051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liphardt J, Dumont S, Smith SB, Tinoco I, Bustamante C. Science. 2002;296:1832–1835. doi: 10.1126/science.1071152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE. Nature protocols. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Schreiber G, Fersht AR. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Selzer T, Albeck S, Schreiber G. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:537–541. doi: 10.1038/76744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sigalov AB. Prog Biophys Mol Bio. 2011;106:525–536. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.