Abstract

Aortoesophageal fistulae (AEF) are rare and are associated with very high mortality. Foreign body ingestions remain the commonest cause of AEF seen in children. However in a clinical setting of tuberculosis and massive upper GI bleed, an AEF secondary to tuberculosis should be kept in mind. An early strong clinical suspicion with good quality imaging and endoscopic evaluation and timely aggressive surgical intervention helps offer the best possible management for this life threatening disorder. Our case is a 10-year-old boy who presented to the pediatric emergency with massive bouts of haemetemesis and was investigated and managed by multidisciplinary team effort in the emergency setting.

KEY WORDS: Aorto-esophageal fistula, children, tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Aortoesophageal fistula (AEF) in children is rare and results in very high mortality because of massive bleeding. Foreign body ingestions remain the commonest cause of AEF in children.[1–4] Tuberculosis as a cause of AEF has been reported in adults. It is usually difficult to control bleeding by any endoscopic measures or intraesopahgeal pressure application by Sengstaken Blakemore tube. Patients of AEF usually require extensive resuscitation efforts before definitive treatment. Surgical exploration of the thoracic esophagus and aorta and repair of the fistula remains the only hope for survival.

CASE REPORT

A 10-year-old boy presented to the pediatric emergency with bouts of massive hematemesis, passage of fresh blood per rectum, and melena for 2 h. There was a previous history of massive hematemesis 2 weeks back, which resolved spontaneously after 2 units of blood transfusion. He had a history of anorexia and weight loss over the last 1 month. There was no history of trauma, foreign body, or corrosive ingestion. On examination, the child was restless and irritable. He had marked pallor, a low volume pulse, and a pulse rate of 140 per minute and blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg. Systemic examination was unremarkable. The child was resuscitated with fluids and packed red blood cells (PRBCs). However, massive hematemesis and melena continued resulting in progressive worsening of hemodynamic status over the next few hours. Resuscitation was stepped up with transfusion of multiple PRBC units to make up for the ongoing blood loss, and the child was intubated for prevention of aspiration and put on support. The preliminary reports revealed hemoglobin of 2.5 g/dl, platelet count of 200,000/mm3, and a normal prothrombin time. Upper GI endoscopy showed active esophageal bleeding and a pale esophageal mucosa with an ulcerated lesion of around 1 cm in diameter with overturned margins and a clot over it, in mid-esophagus at 25 cm from the incisors. Rest of the esophagus was unremarkable. Hemostatic procedures in the form of sclerotherapy around the lesion were tried, but re-bleeding occurred during the procedure. Child was shifted to pediatric intensive care unit, where resuscitative measures were continued and ionotropes were started. Imaging with contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan thorax showed multifocal parenchymal consolidation and marked soft tissue thickening in mediastinal planes with esophageal mural and periesophageal thickening. The intravenously administered contrast was seen filling the esophageal lumen with a linear track extending from medial aortic border to the esophagus [Figure 1]. Based on clinical, endoscopic, and imaging findings, a diagnosis of AEF was made and the child was taken up for emergency thoracotomy. On exploration by left thoracotomy, mediastinum was studded with multiple necrotic nodes and inflammatory soft tissue. Mid esophagus and the aorta were encased in dense inflammatory tissue preventing separation of the esophagus from the aorta. Therefore, the aorta was transected between clamps to approach the AEF [Figure 2], which was then dissected off the posterior wall of the aorta. Damaged segment of the aorta was resected and continuity restored using Dacron graft within 20 minutes without cardiopulmonary bypass. A partial esophagectomy of the densely inflamed esophagus, closure of distal esophageal stump, and cervical esophagostomy was performed. A gastrostomy and feeding jejunostomy were also placed. In the post-operative period, the inotropes were gradually tapered and stopped, and the child was weaned of the ventilator over the next few days. The histopathological examination of lymph nodes, aortic wall, and esophagus showed presence of necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas compatible with tuberculosis [Figure 3]. The Mantoux test done in postoperative period was strongly positive (18-mm induration). There was global neurological impairment with poor recovery secondary to neurological injury as a result of massive preoperative blood loss and hypoxemia. However, the child could be discharged home on anti-tubercular drugs and enteral nutrition through the feeding jejunostomy, pending an esophageal replacement.

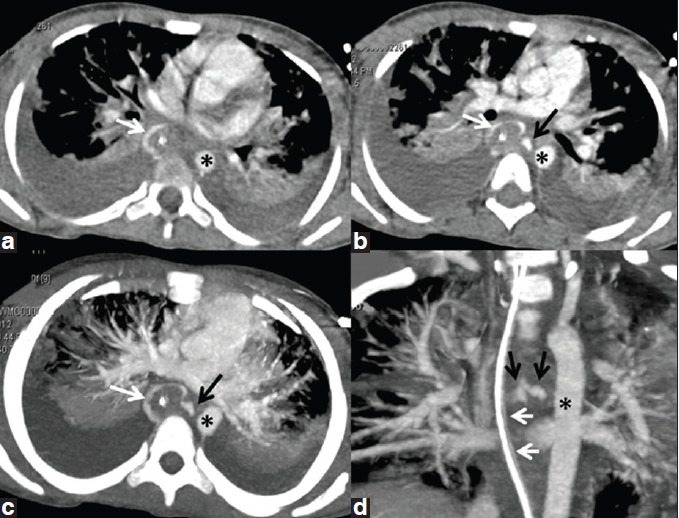

Figure 1.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT chest (a and b) showing linear track (black arrow, b-d) extending from medial side of thoracic aorta (*, a-d) to the esophagus (inferred from the position of nasogastric tube, white arrows, a-d) curvilinear density around it, due to intravenously administered contrast in the esophageal lumen. The fistulous track is better projected in axial (c) and oblique coronal (d) maximum intensity projections (MIP)

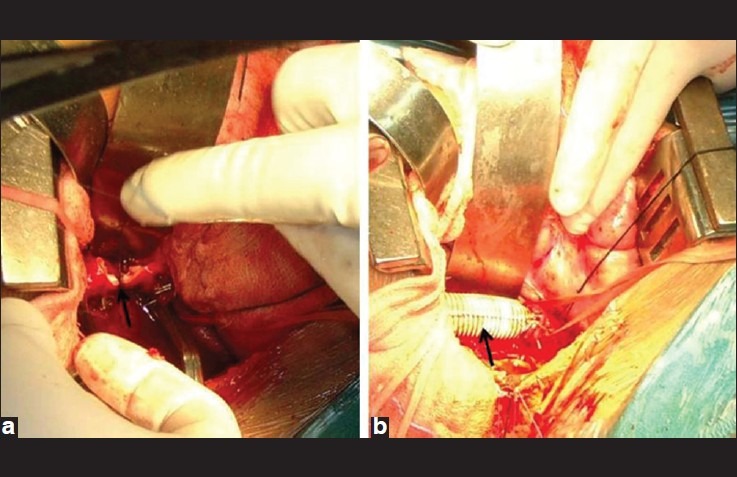

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photographs depicting (a) the transection of aorta (black arrow) between clamps and (b) the completion of aortic repair with dacron graft (black arrow)

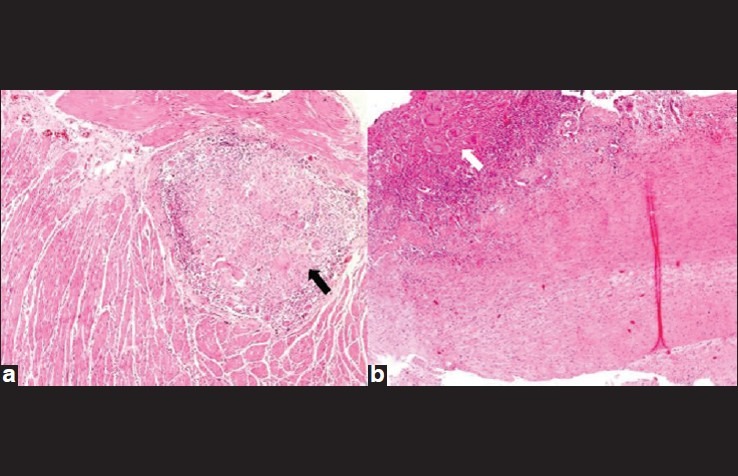

Figure 3.

(a) Esophageal wall 4×, H and E: Shows muscularis propria of esophagus with a large confluent necrotising granuloma (black arrow) with Langhans type of giant cells. (b) Aortic wall 4×, H and E: Shows a granuloma (white arrow) in the tunica adventitia of the vessel wall

DISCUSSION

In children, many etiologies for AEF have been described in various case reports. Most commonly, ingestion of sharp, penetrating, and hollow foreign bodies have been implicated.[1–4] Ingestion of button batteries that cause erosion of the esophageal and aortic wall once the contents are released is also a known cause.[5] Ingestion of foreign body may be forthcoming on history or it may be completely unknown.[2] Continuous nasogastric tube feeding, especially in children with neurological diseases or other reasons, may lead to the formation of AEF.[6] Continuous nasogastric tube insertion in children with known vascular ring has also been reported as a cause.[5] Two children with double aortic arches with prolonged tracheal intubation and/or nasogastric intubation, who subsequently developed AEF have been reported.[7] In another report, a child with right-sided aortic arch with prolonged salivary bypass tube in distal esophagus was reported to have developed an AEF.[8] An aortic aneurysm can sometimes erode the esophagus, leading to the formation of a communication between aorta and esopahagus.[9] One case of a child developing AEF due to severe esophagitis caused by ingestion of a Dieffenbachia leaf has been reported.[10]A case has been reported in a child, where AEF was found peri-operatively, but no cause could be ascertained.[11]

Tuberculosis as a cause of AEF has been reported in adults,[12–16] but not in children. Tuberculous AEF’s develop as a result of esophageal tuberculosis,[13–15] mediastinal tuberculosis,[12] or tubercular aortitis.[16] These fistulae usually develop in the mid-esopahagus around carina, as was the case with our patient. There may or may not be any evidence of associated pulmonary tuberculosis. The patient described is the first of its kind reported in pediatric population. This patient had active mediastinal tuberculosis involving mediastinal nodes, esophagus, and aorta leading to formation of AEF. Surgical treatment of tubercular AEF can be carried out through left thoracotomy approach by excision of damaged part of thoracic aorta and esophagus with aortic graft replacement and esophageal replacement with stomach simultaneously.[16]. Post-operatively anti-tuberculous medications should be started.[16]

AEF usually results in a very high mortality due to massive bleeding that ensues. Sometimes the bleeding is too massive to allow for any investigations or any surgical intervention. It is usually difficult to control bleeding by any endoscopic measures or intraesopahgeal pressure application by Sengstaken Blakemore tube. Patients of AEF usually require extensive resuscitation efforts before definitive treatment is instituted and some succumb to the bleed even before definitive management. Surgical exploration of the thoracic esophagus and aorta and repair of the fistula remains the only hope for survival. Even after surgery, mortality is high due to massive exsanguinations that has already taken place.[17] Neurological disability that occurs in these patients is because of massive blood loss, hypoxia, tubercular spinal arteritis, and spinal ischemia during repair of aortic defect. In our case, neurological impairment was global due to hypoxia as a result of repeated resuscitation and massive blood transfusion. In case of tubercular spinal arteritis and spinal ischemia, neurological disability is primarily localized to lower limbs and less likely to be global.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McComas BC, van Miles P, Katz BE. Successful salvage of an 8-month-old child with an aortoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:1394–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)91043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuth EA, Stucke AG, Cohen RD, Jaquiss RD, Kugathasan S, Litwin SB. Successful resuscitation of a child after exsanguination due to aortoesophageal fistula from undiagnosed foreign body. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1025–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200110000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiraki K. Aortoesophageal conduit due to a foreign body. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996;17:347–8. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199612000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigalet DL, Laberge JM, DiLorenzo M, Adolph V, Nguyen LT, Youssef S, et al. Aortoesophageal fistula: Congenital and acquired causes. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1212–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeza Herrera C, Cortes García R, Velasco Soria L, Velázquez Pino H. Aorto-esophageal fistula due to ingestion of button battery. Cir Pediatr. 2010;23:126–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maarouf Z, Kajo K, Plank L, L’auko L, Murgas D. Secondary aortoesophageal fistula as a lethal complication of continuous nasogastric sondage in a child with VATER syndrome. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21:213–5. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2001.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Othersen HB, Jr, Khalil B, Zellner J, Sade R, Handy J, Tagge EP, et al. Aortoesophageal fistula and double aortic arch: Two important points in management. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:594–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McWhorter V, Dunn JC, Teitell MA. Aortoesophageal fistula as a complication of Montgomery salivary bypass tube. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:742–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijhawan S, Patni T, Agrawal S, Vijayvergiya R, Rai RR. Primary aortoesophageal fistula: Presenting as massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Indian J Pediatr. 1996;63:696–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02730825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snajdauf J, Mixa V, Rygl M, Vyhnánek M, Morávek J, Kabelka Z. Aortoesophageal fistula -an unusual complication of esophagitis caused by Dieffenbachia ingestion. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:e29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coates LJ, McNally J, Caputo M, Cusick E. Survival in a 2-year-old boy with hemorrhage secondary to an aortoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:2394–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee OJ, Kim SH. Aortoesophageal fistula associated with tuberculous mediastinitis, mimicking esophageal Dieulafoy’s disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:266–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.2.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catinella FP, Kittle CF. Tuberculous esophagitis with aortic aneurysm fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:87–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwamoto I, Tomita Y, Takasaki M, Mine K, Koga Y, Nabeshima K, et al. Esophagoaortic fistula caused by esophageal tuberculosis: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:381–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00311266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chase RA, Haber MH, Pottage JC, Jr, Schaffner JA, Miller C, Levin S. Tuberculous esophagitis with erosion into aortic aneurysm. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:965–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee EB, Lee SC, Cho JY, Lee JT. Surgery for concomitant aortoesophageal and aortobronchial fistula in tuberculous aortitis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2003;2:234–6. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9293(03)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Liu J, Li J, Hu J, Yu F, Li S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of 32 cases with aortoesophageal fistula due to esophageal foreign body. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:267–72. doi: 10.1002/lary.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]