Abstract

Aim:

To report the results of an early series of patients who underwent modified Koyanagi repair for severe hypospadias.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 24 boys (age: 9 months to 11 years) with proximal hypospadias, chordee, and poor urethral plate underwent modified Koyanagi repair between September 2008 and January 2012. Nine boys had associated penoscrotal transposition that was corrected simultaneously. Vascularized parameatal based foreskin flap was used to correct the hypospadias in a single stage. The follow-up ranged from 6 months to 3.5 years.

Results:

A total of 13 of the 24 children had a good outcome and were voiding normally, while 11 boys developed complications, 3 of which were major and 8 minor. The major complications were complete breakdown (n = 1), meatal and distal neourethral stenosis requiring laying open of distal urethra (n = 1), and glans breakdown (n = 1). The minor complications included fistulae (n = 5), meatal stenosis amenable to dilatation (n = 1), and lateral chordee (n = 1). Majority of the complications were in the initial patients, with successful outcomes in the last 1 year. Most of these complications were successfully managed by minor second procedures.

Conclusion:

Modified Koyanagi repair not only corrects severe hypospadias with chordee but also corrects the associated penoscrotal transposition in a single stage. The results are good once the learning curve is crossed.

KEY WORDS: Chordee, modified Koyanagi, proximal hypospadias, parameatal foreskin flap

INTRODUCTION

Proximal hypospadias with chordee is a complex problem accounting for 10% to 20% of all hypospadias.[1] A few of these are associated with penoscrotal transposition. Since no single technique has given consistently good results, various procedures have evolved, ranging from single stage “tubes” to staged repairs. Modified Koyanagi repair is a one-stage procedure for severe hypospadias with the added benefit of correcting the associated transposition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

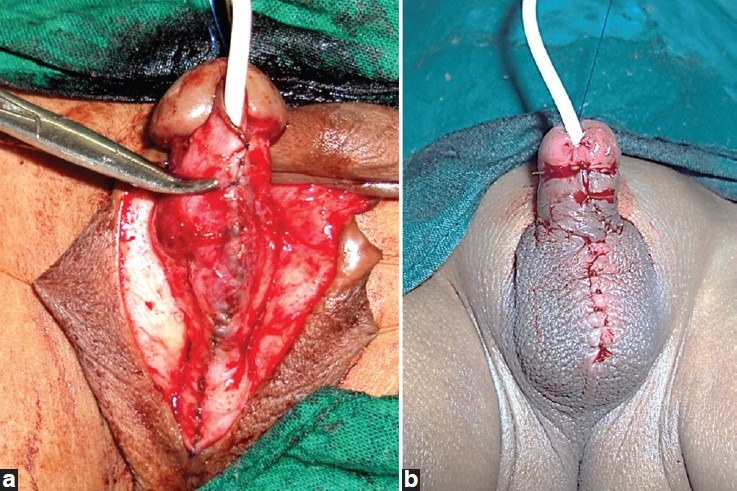

From 2008 to 2011, boys with proximal penile or penoscrotal hypospadias with chordee and poor urethral plate requiring its transection were selected to undergo a modified Koyanagi repair. All these patients were operated by the senior author at either of the two institutions. No patient received preoperative hormone therapy. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia and caudal analgesia. A vertical stay suture was taken with polyprolene on the glans. Skin flaps were marked. For patients requiring simultaneous transposition correction, the parameatal incision was bilaterally extended circumscribing the scrotum [Figure 1]. Urethral plate was divided at the corona. Parameatal based and circumferentially extended foreskin flap was raised. The width of the lateral flaps was 7-8 mm. The urethral plate was mobilized down into perineum to correct chordee. The flap was transposed ventrally by buttonholing the fascia containing the vascular pedicle [Figure 2]. Medial edges of the lateral limbs of the flap were sutured together in the midline to create a wide neourethral plate [Figure 2]. Also, 7/0 or 6/0 (depending on the age) long-term absorbable monofilament sutures (MaxonTm or PDSTm in centres 1 and 2 respectively) were used. The neourethral plate was then tubularised over a silastic 8F catheter using the same suture [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Marking of skin flaps

Figure 2.

Parameatal flap transposed ventrally and their medial edges sutured to form wide urethral plate

Figure 3.

Tubularization of flap and completed repair

Subsequently, glans wings were raised and meatoplasty and glansplasty completed. Finally, a tunica vaginalis flap was used as reinforcement for the repair. The Byar’s flap created from the dorsal hood was brought around ventrally to complete the skin cover [Figure 3]. In patients with transposition, the scrotal flaps were rotated medially and downward and sutured at the base of the penis ventrally. A standard pressure dressing was applied. Only a single dose of preoperative antibiotic was used (cefotaxime 50 mg/kg in centre 1 and cefazolin 50 mg/kg in centre 2). Postoperatively, all patients received oral analgesics, laxative (lactulose), and anticholinergic (oxybutinin) until the catheter was removed. In centre 2, all children were discharged as day care and called back on postoperative day 7 for dressing and catheter removal, while, in centre 2, the dressings were removed after 48 h and the patients were discharged following catheter removal on postoperative day 7. All patients underwent a single calibration 1 week after catheter removal and subsequently if necessary.

The patients were assessed at follow-up for urinary stream, glans configuration, straightness of shaft, and completeness of transposition correction. Absence of any complications, normal good caliber, and uninterrupted stream qualified for a good functional outcome. Conical glans, straight shaft, and absence of penoscrotal transposition were considered a good cosmetic result.

RESULTS

A total of 24 boys (age: 9 months to 11 years) underwent the repair. Of which, 9 boys had associated transposition. The follow-up period ranged from 6 months to 3.5 years. The overall complication rate was 45.8% (n = 11), of which 12.5% (n = 3) were major, 20.8% (n = 5) fistulas, and 12.5% (n = 3) minor. Major complications included one each of complete breakdown, glans breakdown (that was subsequently repaired), and urethral stenosis (that needed laying open of distal neourethra). The remaining were minor complications; 5 boys developed a fistula, of whom, 3 underwent fistula closure, 1 closed spontaneously and 1 is awaiting fistula closure [Table 1]. Also, 2 boys had meatal stenosis that was amenable to dilatation and 1 boy developed lateral chordee due to scarring of the transposition correction suture line. The child with complete failed repair and the one with lateral chordee are awaiting further surgery. All the other patients had good cosmetic and functional results.

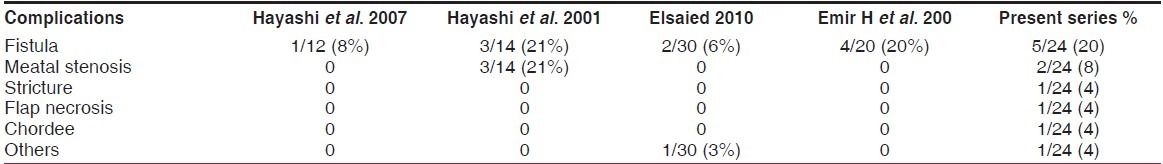

Table 1.

Clinical data with complications

DISCUSSION

Koyanagi repair uses a vascularized parameatal based foreskin flap to provide the necessary long urethroplasty. The original Koyanagi repair used a Y-shaped flap[2] that was later modified to a “lasso” shaped one. Although it was first reported more than 25 years ago, it did not become popular due to high complication rates (47%).[2] This was attributed to the fact that no specific care was taken to preserve blood supply of the flap.[3] This deficit was later corrected in the modified Koyanagi repair put forth by Koff et al.,[4] and Hayashi et al.,[3] Hayashi also modified the Koyanagi repair by preserving a wide vascular pedicle for the distal skin flaps and by utilizing the distal urethral plate as the base for the distal neourethra. He reported that this lowered the incidence of complications (8% in his series).[5] Recent publications report success rate of the modified Koyanagi repair varying from 70% to 82%[6] [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparative analyses of complications in different series

Modified Koyanagi repair is based on a vascularized flap, and blood supply to that must be well preserved. In this series, complications were seen initially when broad-tip bipolar cautery was used. Non-availability of fine-tip bipolar may have hampered the fragile blood supply of the pedicle and the resulting ischemia, which is the cause of complications. This is one reason some authors recommend suture ligation of only significant bleeders instead of using bipolar cautery.[7] In addition, the major complications occurred during the early period of the study and are attributed to the learning curve. It is important to ensure that a flap width of 7-8 mm is maintained throughout. Flap can be accidentally narrowed at the site of native meatus and at the junction between ventral and dorsal skin. This results in stricture and/or fistula formation. Hence, marking skin incision with indelible ink prior to incision is mandatory.

Some authors recommend preoperative HCG (250 IU intramuscular twice weekly for 5 weeks[7] or 80 IU/kg once a week for 3 weeks[6] ). This is said to increase vascularity and may improve the end result.

The results of the modified Koyanagi are comparable to those of other single-stage repairs.[6]

Although it appears that the complication rate with this technique is significantly high, our data reveals that most complications are self-limiting ones or amenable to minor second-stage procedures. The advantages of this procedure outweigh the possible complications. First of all, this procedure eliminates anastomosis between neourethra and native urethra. There is no torsion or bulking of the penile shaft as is apparent in other repairs.[3] Finally, the major dissection and tubularization is performed on a virgin tissue plane without underlying scar affecting vascularity.[7] This repair also allows simultaneous repair of associated penoscrotal transposition with a good cosmetic and functional outcome.

CONCLUSION

Modified Koyanagi repair in a select group of severe hypospadias with chordee gives a good cosmetic and functional result. Complications rate is low once the learning curve is crossed as it allows simultaneous correction of associated transposition with a good cosmetic outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Horton CE, Sadove RC, Devine CJ. Reconstruction of the male genital defects: Congenital. In: McCarthy JG, editor. Plastic Surgery. Vol. 6. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990. pp. 4153–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koyanagi T, Matsuno T, Nonomura K, Sakakibara N. Complete repair of severe penoscrotal hypospadias in 1 stage: Experience with urethral mobilization, wing flap-flipping urethroplasty and glanulomeatoplasty. J Urol. 1983;130:1150–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Nakane A, Kohri K. The modified Koyanagi repair for severe proximal hypospadias. BJU Int. 2001;87:235–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emir H, Jayanthi Vr, Nitahara K, Danismend N, Koff SA. Modification of the Koyanagi technique for the single stage repair of proximal hypospadias. J Urol. 2000;164(3 Pt 2):973–6. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Nakane A, Kurokawa S, Maruyama T, et al. Neo-modified Koyanagi technique for the single-stage repair of proximal hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3:239–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elsaied A, Saied B, El-Ghazaly M. Modified Koyanagi technique in management of proximal hypospadias. Ann Pediatr Surg. 2010;6:22–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayanthi VR. The modified Koyanagi hypospadias repair for the one-stage repair of proximal hypospadias. Indian J Urol. 2008;24:206–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.40617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]