Abstract

Background:

Some of the highest exposures to air pollutants in developing countries occur inside homes where biofuels are used for daily cooking. Inhalation of these pollutants may cause deleterious effects on health.

Objectives:

To assess the respiratory and other morbidities associated with use of various types of cooking fuels in rural area of Nagpur and to study the relationship between the duration of exposure (exposure index [EI]) and various morbidities.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 760 non-smoking, non-pregnant women aged 15 years and above (mean age 32.51 14.90 years) exposed to domestic smoke from cooking fuels from an early age, working in poorly ventilated kitchen were selected and on examination presented with various health problems. Exposure was calculated as the average hours spent daily for cooking multiplied by the number of years. Symptoms were enquired by means of a standard questionnaire adopted from that of the British Medical Research Council. Lung function was assessed by the measurement of peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). PEFR less than 80% of the predicted was considered as abnormal pulmonary function.

Results and Conclusions:

Symptoms like eye irritation, headache, and diminution of vision were found to be significantly higher in biomass users (P < 0.05). Abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, and cataract in biomass users was significantly higher than other fuel users (P < 0.05). Moreover an increasing trend in prevalence of symptoms/morbid conditions was observed with increase in EI. The presence of respiratory symptoms/morbid conditions was associated with lower values of both observed and percent predicted PEFR (P < 0.05 to 0.001). Thus women exposed to biofuels smoke suffer more from health problems and respiratory illnesses when compared with other fuel users.

Keywords: Biomass, chronic bronchitis, cooking fuel, health effects, indoor air pollution

Introduction

It is not only the ambient air quality in the cities but also the indoor air quality in the rural areas that are causing great concern due to its ill effects on health. In fact in the developing world the highest air pollution exposures occur in the indoor environment. Air pollutants that are inhaled have serious impact on human health affecting particularly the lungs and the respiratory system; as they are released in close proximity to people; they are also taken up by the blood and circulated in the body. Strong association between bio-fuel exposure and increased incidences of respiratory problems like chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (e.g., chronic bronchitis), bronchial asthma, etc. have been documented. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has assessed the contribution of a range of risk factors to the burden of disease and revealed indoor air pollution as the eighth most important risk factor and responsible for 2.7% of the global burden of disease. It has been stated by WHO that a pollutant released indoors is 1000 times more likely to reach the lung than that released outdoors.(1,2)

The present study is an attempt to study the respiratory and other morbidities among rural women involved in household cooking with four different kinds of cooking fuels, i.e., biomass, kerosene stove, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and mixed (combination of two or more cooking fuels) and to study the relationship between the duration of exposure (exposure index [EI]) and various morbidities.

Materials and Methods

A house-to-house survey was carried out in five areas of Raipura village of district Nagpur which is a field practice area of rural health training center, under Preventive and Social Medicine Department, Indira Gandhi Government Medical College, Nagpur. As per the demographic data obtained from health survey register of primary health center, Hingna, the total population of Raipura was 7635. Out of these, rural health training center adopted 500 families covering approximately a population of 2,500. Eligible subjects were found to be 760 women.

Inclusion criteria

Women aged 15 years and above involved in cooking

Non-smokers and non-pregnant women.

Exclusion criteria

Women not involved in cooking

Smoking and pregnant women.

Before proceeding for the main study, the proforma was tested by conducting a pilot study in 100 women. The study was conducted over a period of 1 year. The study area was totally free from industrial and atmospheric pollution.

The study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Respiratory symptoms in detail were enquired by means of a standard questionnaire adopted from the British Medical Research Council (MRC), and chronic bronchitis was diagnosed from the presence of cough with expectoration for 3 months in a year for at least two consecutive years on the recommended criteria of MRC.(3) Bronchial asthma was diagnosed on the history of episodic cough with wheezing, presence of rhonchi and response to bronchodilators. Other respiratory symptoms noted were dry cough (falling short of the definition of chronic bronchitis); dyspnoea in the absence of any clinical cardiopulmonary disease; and nasal irritation. Various non-respiratory symptoms like eye irritation, diminution of vision, cataract, headache, giddiness and body ache were also noted. Hemoglobin estimation was done by Sahali’s hemoglobinometer method and women with hemoglobin less than 12 g % were considered as anemic according to WHO criteria.(4)

Any specific history of relationship of cooking to symptomatology was also inquired. In addition, the abnormal pulmonary function of the study subjects was assessed by the measurement of peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). PEFR was measured in liters/minute with a calibrated Mini Wright’s Peak Flow Meter with the subject comfortably seated. Instructions and method of carrying out the test was demonstrated to the subjects. Each subject made three PEFR maneuvers, and the highest value was recorded, since this parameter requires maximum effort.

Observed PEFR was calculated on the basis of age in years and height in centimeters. In this study the predicted values for PEFR in females were calculated by using the equation of PEFR = 3.310H - 1.865A - 81.0 where H = height in cm, A = age in years.

PEFR less than 80% of the predicted was considered as abnormal pulmonary function.(5)

Each woman was subjected to a detailed history including the history of smoking, location of the kitchen, adequacy of ventilation, type of cooking fuel used, and clinical examination. Exposure index (EI)(6) was calculated in each woman by multiplying the number of hours spent in a day for cooking and the number of years of cooking. In the study, mean time of exposure was 20.90 ± 15.48 years and mean EI was 62.57 ± 50.85. Height was measured in standing position and without shoes, and weight was recorded with minimal clothing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated. A control group of women with same socio-economic status who are not exposed to these cooking fuels could not be formed in this study.

Statistical analysis

Percentage, mean and standard deviation was calculated. The Chi-square test trend and analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Out of 760 women studied, 252 (33.2%) were using exclusively biomass fuels for cooking; 73 (9.6%) were using exclusively kerosene stove; 192 (25.3%) were using exclusively LPG and 243 (31.9%) were using mixed fuel (combination of two or more).

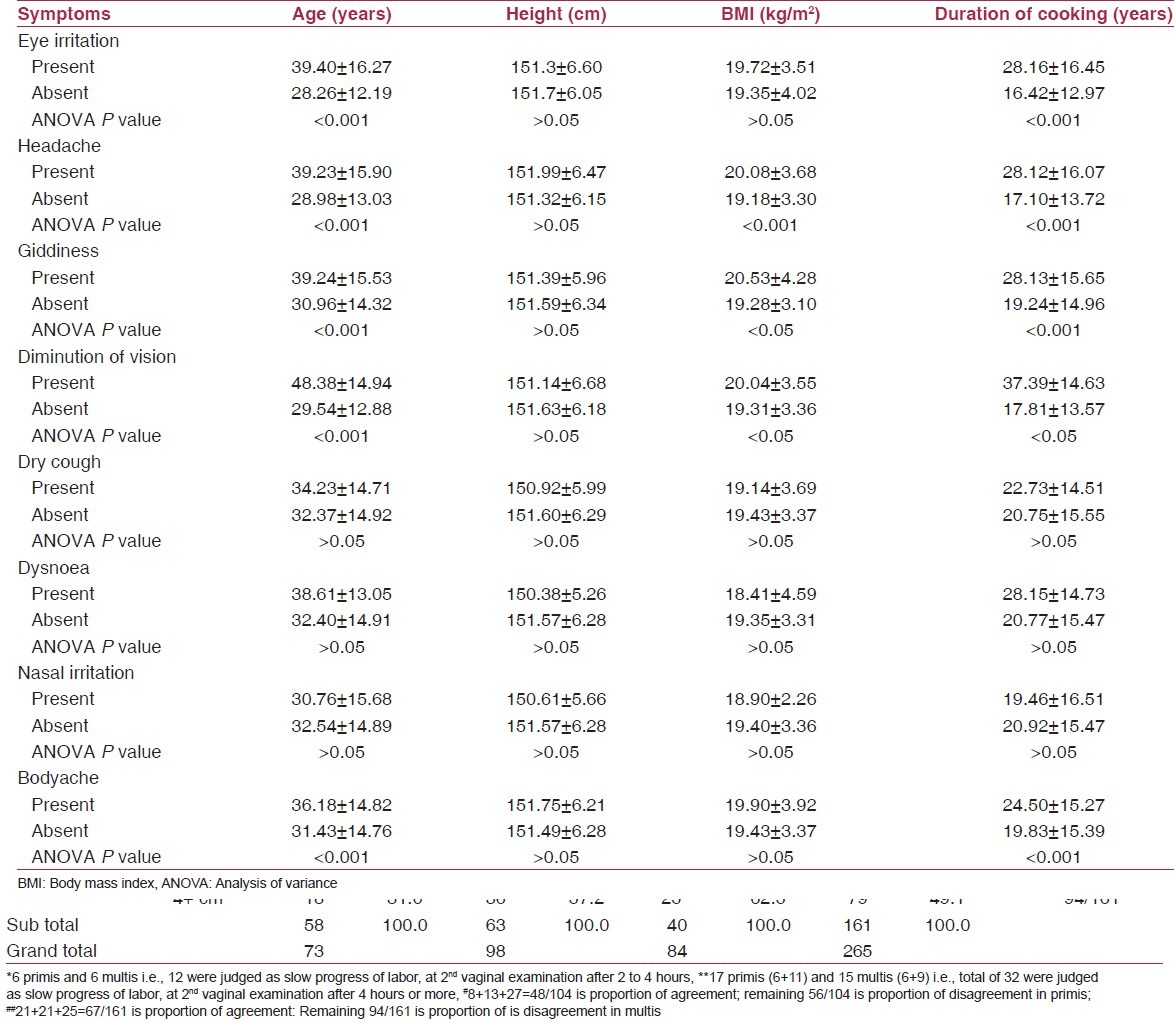

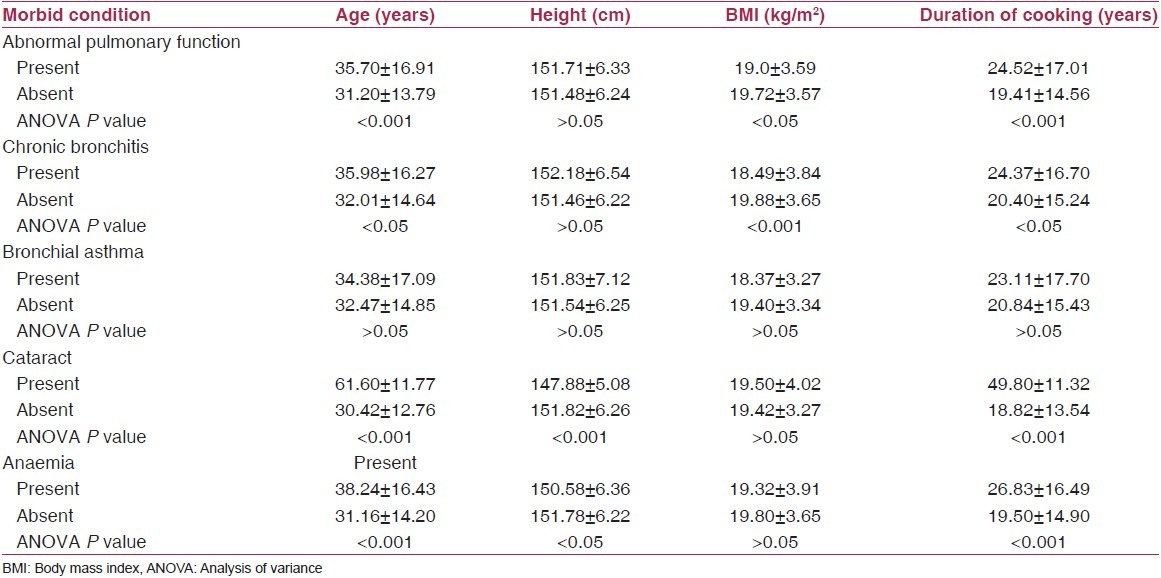

Table 1 shows the distribution of age, height, BMI, and duration of cooking according to different types of symptoms (eye irritation, headache, giddiness, diminution of vision, dry cough, dysnoea, nasal irritation, and body ache) encountered by study subjects. The symptomatic women had higher age (P < 0.05) and low BMI. Similarly the symptomatic women had higher duration of exposure (P < 0.05). The height was similar in all the groups irrespective of presence or absence of symptoms/morbid conditions. Women with morbid conditions (abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, bronchial asthma, cataract, and anemia) had significantly higher age and greater duration of exposure (P < 0.05) except for bronchial asthma where it did not reach statistical significance though the mean age and EI was higher [Table 2].

Table 1.

Distribution of age, height, body mass index and duration of cooking among subjects according to presence or absence of symptoms (mean±SD)

Table 2.

Distribution of age, height, body mass index and duration of cooking among subjects according to presence or absence of morbid conditions (mean±SD)

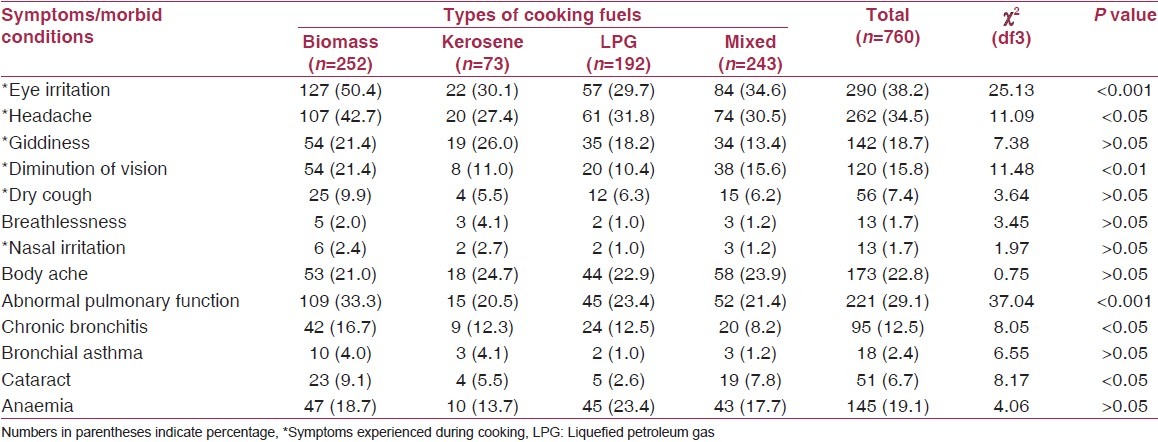

Table 3 shows the comparisons of symptoms/morbidities in different fuel users. Subjects experienced various symptoms like eye irritation, headache, giddiness, diminution of vision, dry cough, and nasal irritation during cooking. The prevalence of symptoms like eye irritation, headache, diminution of vision, and dry cough were found to be more among biomass users as compared with kerosene, LPG, and mixed fuel users. Chi-square test across all cooking device categories revealed statistically significant difference for eye irritation, headache, and giddiness (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the prevalence of morbid conditions was found to be more among biomass users (abnormal pulmonary function [33.3%], chronic bronchitis [16.7%], bronchial asthma [4%], cataract [9.1%], and anemia [18.7%]) when compared with other fuels. However, the difference was found to be statistically significant for abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, and cataract (P < 0.05). The overall prevalence of abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, and anemia was found to be 29.1%, 12.5% and 8.17%, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparison of symptoms/morbidities in different fuel users

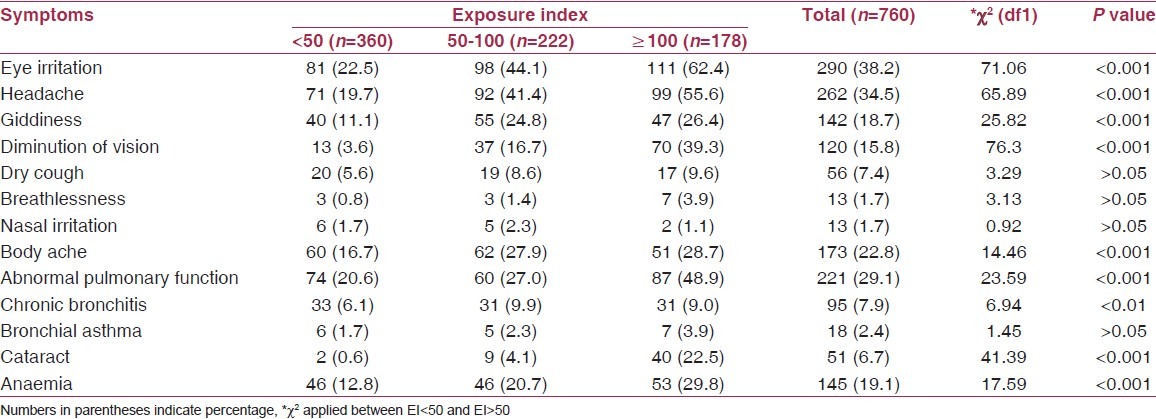

It can be seen from Table 4 that a significant increasing trend in the prevalence rate of symptoms (eye irritation, headache, giddiness, diminution of vision, and body ache) and morbid conditions (abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, cataract, and anemia) was found with increase in EI (P < 0.05). A statistically significant difference was found in various symptoms/morbid conditions when EI < 50 was compared with EI > 50.

Table 4.

Symptoms/morbid conditions according to exposure index

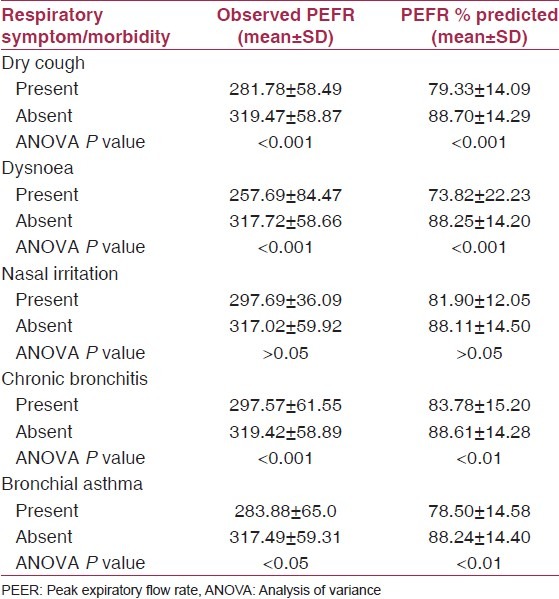

Table 5 shows the lung function parameter PEFR (observed and % predicted) among subjects with respiratory symptoms/morbidities. The presence of symptoms/morbid conditions (dry cough, dysnoea, abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, bronchial asthma) was associated with lower values of both observed and percent predicted PEFR (P < 0.05 to 0.001). The asymptomatic women had significantly higher values (observed and % predicted PEFR) as compared with symptomatic women (P < 0.05 to 0.001).

Table 5.

Peak expiratory flow rate among study subjects with respiratory symptom/morbidities

Discussion

The study evaluated the role of domestic smoke on health of 760 non-smoking rural women exposed to different types of cooking fuels. Women presenting with various symptoms/morbid conditions were older and had greater duration of cooking.

The symptoms like eye irritation, headache, and diminution of vision were found to be significantly higher in biomass users (P < 0.05). Abnormal pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, and cataract in biomass users was significantly higher than other fuel users (P < 0.05). Moreover, an increasing trend in prevalence of symptoms/morbid conditions was observed with increase in EI. Similar types of observations have been reported by other investigators. Study carried out at National Institute of Occupational Health, Ahmedabad,(7) reported higher incidence of cough, cough with expectoration, dysnoea, and lung function abnormalities among housewives cooking with smoky fuels who also complained of pain and watering in the eyes while cooking. Ellegard,(8) proposed eye irritation in the form of tears or smarting eyes during cooking time (tears while cooking [TWC]) to be a useful determinant of indoor air pollution from cooking related sources and also reported that persons with TWC had more respiratory symptoms. It may also lead to cataract. The mechanism is thought to involve absorption and accumulation of toxins that lead to oxidation.

Malik,(9) in his survey of 2180 women found an increased incidence of chronic bronchitis in chulla users (5%) compared with LPG (1.5%) and kerosene (1.3%). Pandey et al.,(10,11) from Nepal reported a high prevalence of chronic bronchitis in 18.9% cases of non-smoking, rural women and also noted a dose-response relationship between domestic smoke pollution and chronic bronchitis. This would not have been expected if cigarette smoking, being commoner in men, had been the main cause. In our study, 10.1% women of chronic bronchitis had moderate to heavy exposure (EI above 100). Another study conducted in North India on 3701 women using different types of cooking fuels found that women using mixed fuel experienced more respiratory symptoms (16.7%), followed by biomass (12.6%), stove (11.4%), and LPG (9.9%) users. However, chronic bronchitis in chulla users was significantly higher than that in kerosene, LPG, and mixed fuel users. Dysnoea and postnasal drip were higher in women using mixed fuels.(6)

Our study reported an overall high prevalence of chronic bronchitis of 12.5% and when analyzed for different cooking devices, it was 16.7% for biomass users. This could be attributed to smoke emissions from biomass fuels (wood, agricultural waste, and animal dung) containing important pollutants that adversely affect health such as suspended particulate matter, polyaromatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic organic matter which includes a number of known carcinogens called Benzo (a) Pyrene, as well as gaseous pollutants like carbon monoxide and formaldehyde. These pollutants cause irritant or inflammatory action on the conjunctiva and the mucous linings of the respiratory tract from the nose to the bronchi. Aldehydes, phenols, and toluene are among the important hydrocarbons that have an irritant action. These particles when breathed in, lodge in lung tissues and cause lung damage and respiratory problems.(12) Oxidative stress may be a component, as oxidizing radicals are present in biomass smoke and also released by inflammatory cells.(13)

Our demonstration of lowered values of observed and percent predicted PEFR is consistent with the findings of Behera et al.,(6) who found lowest values of [Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV 1 )], and PEFR among symptomatic women.

Thus in conclusion the present study showed that the women using biomass fuel for cooking suffered more from respiratory and other morbidities than the women using other types of cooking fuels. Also, the morbidities found to be increased with increase in duration of cooking and EI.

Switching to cleaner alternatives such as electricity, solar energy, improved stoves, or hoods that vent health damaging pollutants to the outside and behavioral changes may decrease the health effects of indoor air pollution.

There are number of health problems for which the available evidence is very limited or inconsistent. Efforts should also be made to strengthen emerging exposure-response relationships, particularly for common and serious health outcomes such as acute lower respiratory infections. Further research is required for improving information on dose-response relationships between indoor air pollution and various health effects (e.g., increased mortality and morbidity risks).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Balakrishnan K, Mehta S, Kumar S, Kumar P. Exposure to indoor air pollution: Evidence from Andhra Pradesh, India. Regional Health Forum. World Health Organisation. 2003;7:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Last accessed on 2011 Jun 20]. Available from: http://www.edugreen.teri.res.in/explore/air/health.htm .

- 3.Medical Research Council. Standardized questionnaires on respiratory symptoms. BMJ. 1960;2:1665. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. Nutritional anemia: Report of a WHO scientific group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1968. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranga Rao TV, Sinha VN, Lanjewar P. Specialized training programme on occupational and environmental Medicine. Industrial Medicine Division, Central Labour Institute Government of India, Ministry of Labour. 2002 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behera D, Jindal SK. Respiratory symptoms in Indian women using domestic cooking fuels. Chest. 1991;100:385–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Occupational Health, Ahmedabad. Annual Report. 1982. Domestic source of air pollution and its effects on the respiratory systems of housewives in Ahmedabad; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellegård A. Tears while cooking: An indicator of indoor air pollution and related health effects in developing countries. Environ Res. 1997;75:12–22. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1997.3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik SK. Exposure to domestic cooking fuels and chronic bronchitis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1985;27:171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey MR. Prevalence of chronic bronchitis in a rural community of the Hill Region of Nepal. Thorax. 1984;39:331–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.5.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandey MR. Domestic smoke pollution and chronic bronchitis in a rural community of the Hill Region of Nepal. Thorax. 1984;39:337–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.5.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Koning HW, Smith KR, Last JM. Biomass fuel combustion and health. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63:11–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Repine JE, Bast A, Lankhorst I. Oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oxidative stress study group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:341–57. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9611013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]