Abstract

The oral cavity harbors a diverse and abundant number of complex oral pathogens causing different oral diseases. The development of dental caries and periodontal diseases has been found to be closely associated with various gram positive and gram negative microrganisms. Miswak, a natural toothbrush, has been documented as a potent antibacterial aid and its use is encouraged in different countries because of its good taste, texture, availability, cost and beneficial effect on teeth and supporting tissues. Different researches have been carried out to evaluate the antimicrobial effects of Miswak. This review encompasses the efficacy of Miswak on suppression of oral pathogens with respect to conducted on fungi as well as cariogenic, periodontal and endodontic bacteria.

Keywords: Antimicrobial effects, Miswak, oral pathogens, salvadora persica

INTRODUCTION

Oral hygiene measures have been practiced by different populations globally since antiquity. The oral hygiene measures in certain population are adapted depending on factors, such as cultural background, religious norms, educational level, and socio-economic status.[1] The widely used methods for maintaining oral health are toothbrushes and dentifrices. The traditional toothbrush or chewing stick called “Miswak” has had been used widely by different civilizations for centuries. It was initially used by Babylonians around 7000 years ago[2] followed by Greek and Roman empires. Chewing sticks were also used by Jewish, Egyptian as well as by old Japanese-communities.[3] It is believed that the Europe was unfamiliar with such traditional hygienic methods of chewing stick until about 300 years ago. Today, chewing sticks are being widely used in Asia, Africa, South America, and throughout the Islamic countries.[2,4] It is known with different other names in different cultures as siwak or arak [Figure 1].[3]

Figure 1.

Miswak

Unlike other religious communities, which have been using chewing stick, Islam emphasized the use of Miswak for oral hygiene by incorporating it as a holy practice around 543 Anno Domini.[5] Miswak is used to attain ritual purity and higher spiritual status and also used to get white and shiny teeth. Muslims use Miswak for cleaning teeth 5 times a day during ablution before worship. Some Muslims use Miswak fewer than 5 times a day or use a conventional toothbrush instead.[5,6] Studies have demonstrated that Miswak has high efficacy compared to conventional toothbrush without toothpaste that makes us to understand why Islam emphasized the use of Miswak.[3] It is a strong belief of Muslims that the use of Miswak has the potential to increase disease resistance in humans.[6,7]

There are several shrubs and local tree being used as chewing stick in different parts of the world, which are selected due to good taste, texture like long bristle, availability and their beneficial effect on supporting tissues and teeth.[3] There are around 173 different types of trees, which can be used as chewing sticks, belonging to the families Acacia, Fabaceae, Terminalia, Combretaceae, Lasianthera, Icacinaceae, Gouania, and Rhamnaceae.[8,9] The most popular chewing stick or fibrous rolled sponges include Salvadora persica and Azadirachta indica[10,11] [Table 1]. A widely used Miswak stick, so called S. persica or Arak tree [Figure 2], is often known by the name of tooth brushing tree in European countries or tooth pick tree in Middle East. It belongs to the species of Salvadora from the family of Salvadoraceae.[9]

Table 1.

Different types of chewing sticks

Figure 2.

Salvadora persica (arak tree)

It is a small upright shrub, which is 3 m in height and 30 cm in diameter.[2] It has white branches, aromatic roots, as well as warm and pungent taste. Its fruits are small size and round shape.[12] It is used in many countries including Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Zaire, Uganda, Ethiopia, Ghana, Yemen, Senegal, India, Sudan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan.[13]

The stick is chewed or tapered at one end until it becomes frayed into a brush. Soaking it in water for few hours softens the natural fibers, helping them to separate.[14] The stick is held by one hand in a pen-like grip and the brush-end is used with an up-and-down or rolling motion. A two-finger and a five-finger grip technique are used [Figure 3].[15] When the brushy edge is shred after being frequently used, the stick gets ineffective and it is then cut and further chewed to form a fresh edge. In this way, it can be used for few more weeks.[2]

Figure 3.

Application of Miswak

The traditional Miswak with a modern toothbrush is used commonly in Muslim countries. In Saudi Arabia, many youngsters combine modern and traditional oral hygiene methods.[16] In Pakistan, the Miswak is more used among the rural than the urban population. Miswak appears to be more popular among older than the younger generation and for no clear reason appears to be much more common among men than women.[17]

S. persica is considered to be a medicinal herbal plant.[18] It contains salvadorine and trimethylamine, which are shown to exhibit anti-bacterial effects on cariogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans. It has been shown that these active principles support periodontal health,[19] reduces the accumulation of biofilm-like dental plaque formation and exhibits fungistatic activity against Candida albicans.[4]

The traces of tannins, which have anticoagulant properties, are also found in S. persica. The oil extracted from this plant is shown to exert biological activity and is used to cure gall bladder disease, piles, polio, intestinal worm, gonorrhea, and rheumatic joint pain. The oil has also been used for making candles, soaps and are used as a substitute of coconut oil.[20] The fresh root bark paste can be used against vesical catarrh, gonorrhea and as a tonic for low fever. The bark extract is used to relieve gastric and spleen pains because of its ascarifuge properties.[21] Its leaves are bitter in taste and it possesses liver tonic, diuretic, analgesic, astringent, and antiscorbutic properties, which are useful in treating piles, scabies, leucoderma, ozoena.[21,22] Decoction is used to alleviate symptoms of asthma and reduce the intensity of cough. It has been shown that phytochemical extract and essential oil can be used to both prevent and treat most common oral diseases.[23] The other chemical components and its uses are highlighted in Table 2.[16]

Table 2.

Chemical components of Miswak

ANTIMICROBIAL EFFECTS OF MISWAK

Different clinical studies have demonstrated the effects of microbial species in oral cavity. More than 750 bacterial species reside in oral cavity and a number of them have been identified to cause oral diseases.[24] According to several studies, Miswak has been reported to impart an essential antibacterial role, particularly on cariogenic bacteria and periodontal pathogens.[25,26,27] The following anti-microbial effects of Miswak has been reviewed [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial effects of Miswak

The major causative factor of gingivitis and periodontal disease is dental plaque. The process of periodontal disease can be arrested by effective removal of dental plaque. Different studies have identified Miswak as an effective measure for controlling gingivitis. Sofrata et al. demonstrated reduction in plaque and gingival index in Miswak users; however, no effective role was found in interproximal surfaces.[28] Another comparative study was carried out to assess plaque removal in Miswak and toothbrush users. It was clearly evident from the experimental and clinical trials that Miswak was equally effective as traditional method of tooth-brushing on plaque removal.[29]

The salivary pH is lowered to a very significant level after sucrose rinse. Thus, the role of Miswak in acidic oral environment after sucrose intake was studied. Miswak demonstrated elevated levels of plaque pH, indicating its potent role towards caries prevention.[30]

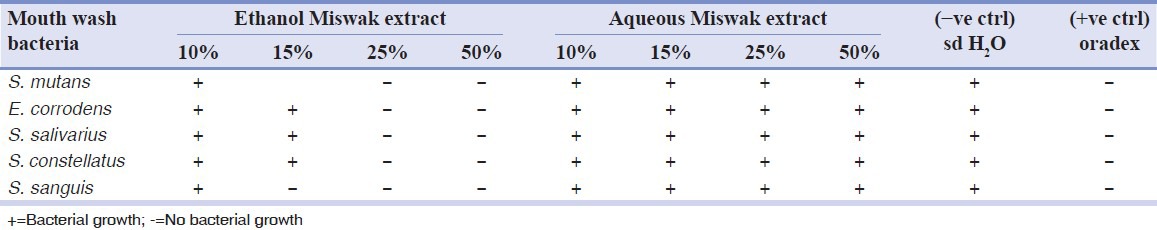

The oral microbes along with dental plaque play a vital role in development of periodontal diseases. An in vitro study was carried out to assess the levels of periodontal bacterial species when treated with aqueous and ethanol extracts of Miswak. The periodontal pathogens under the investigation were gram-positive bacteria including, Eikenella corrodens, as well as gram-negative bacteria including Streptococcus constellatus, Streptococcus sanguis and Streptococcus salivarius. The bacterial species were grown on Muller Hinton II agar and the inhibitory concentrations were observed. The results revealed that the ethanol extract of Miswak showed stronger anti-bacterial action than aqueous extract [Table 3].[31]

Table 3.

The bacterial growth seen with different Miswak extracts concentrations

The progression of gingivitis to more aggressive form of periodontitis has been reported due to predominance of gram-negative bacteria. Miswak demonstrated an assertive anti-microbial activity against gram-negative pathogens including, Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Haemophilus influenza, and Salmonella enteric.[32]

Furthermore, Otaibi et al. exclusively studied the effect of Miswak on A. actinomycetemcomitans by DNA checkboard method and found a significant reduction in the multiplicity of the pathogen[17] [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Digital photograph showing the inhibition of Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans on a blood glucose agar plate in an area around a piece of Miswak

S. mutans has been identified as the most significant microbe contributing to dental caries.[33] The efficacy of Miswak as an anti-dental caries herb was investigated by comparing its effects with the tooth-brush. The reduction in number of S. mutans was greater in Miswak users as compared to toothbrush users[2] [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Marked reduction in levels of Streptococcus mutans in Miswak as compared to toothbrush users

The susceptibility test performed on cariogenic micro-organism illustrated S. mutans being the most susceptible pathogen by Miswak; however, Lactobacillus acidophilus was the least susceptible.[34] A DNA-DNA hybridization method has been carried out revealing inhibitory effect of Miswak on S. mutans, a cariogenic pathogen.[35]

A comparative study between persica mouth-wash and chlorhexidine was carried out to characterize the effects of S. mutans in orthodontic patients. The results enlisted significant reduction in bacterial species but were not documented equivalent to chlorhexidine in potency. However, the complaints of tooth discoloration, unpleasant taste and burning mouth were minimal with persica relative to chlorhexidine mouthwash as illustrated in Table 4.[36] The fluoride releasing property of Miswak makes it an effective oral hygiene tool against caries.[37]

Table 4.

The percent of patients who complained of tooth discoloration and burning mouth in chlorhexidine and persica groups

Candida is responsible for multiple infections of oral cavity and occurs most commonly in immunocompromised patients.[38] Noumi, et al. has documented Miswak as an ant-ifungal agent. The study illustrated the effects of dry and fresh Miswak on candidal species by agar diffusion assay. The results showed enhance activity of dry S. persica against pathogens as compared to fresh extracts.[4]

Different aerobic and anaerobic bacteria reside in bacterial pulp. Miswak was reported as an effective root canal irrigant because it limits bacterial levels during endodontic treatment.[39,40]

The efficacy of Miswak as a root canal irrigant was studied by comparing its effects with other currently used root canal irrigants. 15% Miswak extract was found to be highly effective against all the aerobic and anaerobic microbes in necrotic pulp, which was nearly similar to anti-microbial efficacy of 0.2% chlorhexidine. In addition, sodium hypochlorite showed highest anti-microbial effect, which was nearly significantly similar to Miswak extract and chlorhexidine.[40]

Different extracts of Miswak were evaluated against other oral pathogens. The aqueous extract of S.persica was found to be most active against Staphylococcus aureus followed by L. acidophilus; whereas, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was determined as the least susceptible. On contrary, the methanol extract of S. persica demonstrated least activity against S. aureus.[41]

The anti-bacterial effect of Miswak was studied in vitro on five different microbes. P. gingivalis was found to be most susceptible followed by A. actinomycetemcomitans and H. influenza. However, S. mutans was identified less susceptible and L. acidophilus being least susceptible.[21]

A clinical study was performed on a patient of denture stomatitis. Several strains of microorganisms were isolated from his oral cavity including gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Micrococcus luteus), gram-negative bacteria (P. aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium), and fungi (C. albicans). The results obtained demonstrated inhibition zones around all the micro-organisms with gram-positive bacteria being more active than gram-negative bacteria.[42]

Inhibition zones of different bacterias by Miswak were assessed using blood agar ditch plate method. The results showed that Miswak was active against Streptococcus faecalis only at minimum concentration of 5%; however, S. mutans were inhibited at a higher concentration. On contrary, Miswak was found to be ineffective against S. aureus, S. epidermidis and C. albicans.[43]

Almas, et al. compared the anti-microbial activity of 50% Miswak extract and commercially available mouth-rinses against seven micro-organisms. The pathogens under study were S. faecalis, Streptococcus pyogens, S. mutans, C. albicans, S. aureus, and S. epidermidis. The inhibition zones indicated that all the mouth-rinses under study exhibited anti-microbial activity except Sensodyne mouth-rinse, which did not demonstrate any microbial inhibition. On contrary, 50% Miswak extract showed effective microbial inhibition only against S. faecalis and S. mutan.[44]

CONCLUSION

This review clearly enlightens the significant effect of Miswak as an anti-bacterial agent. The inhibitory role of Miswak on both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and fungi residing in oral cavity has been clearly demonstrated both clinically and experimentally. However, Miswak remains inactive in interproximal surfaces, suggesting its limiting action on micro-flora in these surfaces. The findings evidently support the view that Miswak can be used as a potent dental hygiene method acting against different oral diseases along with additional interproximal cleaning aides. The World Health Organization has also recommended and encouraged the use of these chewing sticks as an effective and alternate tool for oral hygiene (1984 and 2000 international consensus).

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

It is recommended that further research should be carried out to study the role of Miswak on oral infections including, oral ulcers and other lesions in oral cavity

Further work is needed to evaluate the effects of Miswak in tooth-paste

The effects of Miswak on restorative filling materials is yet to be identified

The role of Miswak in patients with periodontitis needs to be assessed

Clinical trials needed to improve evidence on beneficial effects of Miswak and oral health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Asadi SG, Asadi ZG. Chewing sticks and the oral hygiene habits of the adult Pakistani population. Int Dent J. 1997;47:275–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.1997.tb00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almas K, Al-Zeid Z. The immediate antimicrobial effect of a toothbrush and Miswak on cariogenic bacteria: A clinical study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004;5:105–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu CD, Darout IA, Skaug N. Chewing sticks: Timeless natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:275–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.360502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noumi E, Snoussi M, Hajlaoui H, Valentin E, Bakhrouf A. Antifungal properties of Salvadora persica and Juglans regia L. extracts against oral Candida strains. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:81–8. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Sadhan R, Almas K. Miswak (chewing stick): A cultural and scientific heritage. Saudi Dental Journal. 1999;11:80–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos G. The Miswãk, an aspect of dental care in Islam. Med Hist. 1993;37:68–79. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300057690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldini EZ, Ardakani F. Efficacy of Miswak (Salvadora persica) in prevention of dental caries. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci Hlth Serv Winter. 2007;14:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dogan AU, Chan DC, Wurster DE. Bassanite from Salvadora persica: A new evaporatic biomineral. Carbonates and Evaporites. 2005;20:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Njoroge GN, Kaibui IM, Njenga PK, Odhiambo PO. Utilisation of priority traditional medicinal plants and local people's knowledge on their conservation status in arid lands of Kenya (Mwingi District) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Teen RM, Said KN, Abu Alhaija ES. Siwak as a oral hygiene aid in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Int J Dent Hyg. 2006;4:189–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2006.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooda A, Rathee M, Singh J. Chewing sticks in the era of toothbrush: A review. The Internet Journal of Family Practice. 2010;9 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasim M, Daud M, Arif M, Islam R, Iqbal S, Anway Y. Characterisation of some exotic fruits (Morus nigra, Morus alba, Salvadora persica and Carissa opaca) used as herbal medicines by neutron activation analysis and estimation of their nutritional value. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2012;292:653–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Technical report series 713. Geneva: 1984. World Health Organization (WHO). Report. Preventive Methods and Programmes for Oral Diseases; pp. 1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neiburger EJ. The toothbrush plant. J Mass Dent Soc. 2009;58:30–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ronse De Craene L, Wanntorp L. Floral development and anatomy of Salvadoraceae. Ann Bot. 2009;104:913–23. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Otaibi M, Al-Harthy M, Gustafsson A, Johansson A, Claesson R, Angmar-Månsson B. Subgingival plaque microbiota in Saudi Arabians after use of Miswak chewing stick and toothbrush. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:1048–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tubaishat RS, Darby ML, Bauman DB, Box CE. Use of Miswak versus toothbrushes: Oral health beliefs and behaviours among a sample of Jordanian adults. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:126–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2005.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almas K, Skaug N, Ahmad I. An in vitro antimicrobial comparison of Miswak extract with commercially available non-alcohol mouthrinses. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Bayaty FH, AI-Koubaisi AH, Ali NAW, Abdulla MA. Effect of mouth wash extracted from Salvadora persica (Miswak) on dental plaque formation: A clinical trial. J Med Plant Res. 2010;4:1446–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariod AA, Matthaus B, Hussein IH. Chemical characterization of seed and antioxidant activity of various parts of Salvadora persica. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2009;86:857–65. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhtar J, Siddique KM, Bi S, Mujeeb M. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological investigations of Miswak (Salvadora persica Linn) J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:113–7. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.76488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khatak M, Khatak S, Siddqui AA, Vasudeva N, Aggarwal A, Aggarwal P. Salvadora persica. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:209–14. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palombo EA. Traditional medicinal plant extracts and natural products with activity against oral bacteria: Potential application in the prevention and treatment of oral diseases. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep067. 680354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkinson HF, Lamont RJ. Oral microbial communities in sickness and in health. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:589–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolinsky LE, Sote EO. Inhibiting effect of aqueous extracts of eight Nigerian chewing sticks on bacterial properties favouring plaque formation. Caries Res. 1983;17:253–7. doi: 10.1159/000260674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sote EO, Wilson M. In-vitro antibacterial effects of extracts of Nigerian tooth-cleaning sticks on periodontopathic bacteria. Afr Dent J. 1995;9:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al lafi T, Ababneh H. The effect of the extract of the Miswak (chewing sticks) used in Jordan and the Middle East on oral bacteria. Int Dent J. 1995;45:218–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sofrata A, Brito F, Al-Otaibi M, Gustafsson A. Short term clinical effect of active and inactive Salvadora persica Miswak on dental plaque and gingivitis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batwa M, Bergstorm J, Batwa S, Otaibi M. The effectiveness of chewing stick Miswak on plaque removal. Saudi Dental Journal. 2006;18:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sofrata A, Lingström P, Baljoon M, Gustafsson A. The effect of Miswak extract on plaque pH. An in vivo study. Caries Res. 2007;41:451–4. doi: 10.1159/000107931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayaty F, Abdulla M, Hassan M, Roslan S, Hussain S, Said H. Effect of mouthwash extracted from Miswak (Salvadora persica) on periodontal pathogenic bacteria an in vitro study. Science and Social Research. 2010;4:178–81. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sofrata A, Santangelo E, Azeem M, Karlson A, Gustafsson A, Putsep K. Benzyl isothiocyanata, a major component from the roots of Salvadora persica is highly active against gram: Negative bacteria. PLoS One. 2011;6:E23045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desiree S, Anni TD, Felicia S, Sutadi H, Mangundjaja S. University of Kebangsaan Malaysia Kuala Lumpur; 2006. Effect of Salvadora persica in dentifrice on Streptococcus mutans of schoolchildren. Presented at the 11th international pediatric dentistry conference. [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Rahman HF, Skaug N, Francis GW. In vitro antimicrobial effects of crude Miswak extracts on oral pathogens. Saudi Dental Journal. 2002;14:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darout IA, Albandar JM, Skaug N, Ali RW. Salivary microbiota levels in relation to periodontal status, experience of caries and Miswak use in Sudanese adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:411–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salehi P, Momeni Sh. Comparison of the antibacterial effects of persica mouthwash with chlorhexidine on Streptococcus mutans in orthodontic patients. DARU. 2006;14:178–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baeshen HA, Kjellberg H, Lingström P, Birkhed D. Uptake and release of fluoride from fluoride-impregnated chewing sticks (Miswaks) in vitro and in vivo. Caries Res. 2008;42:363–8. doi: 10.1159/000151588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:327–35. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Salman TH, Al-Shaekh Ali MG, Al-Nuaimy OM. The antimicrobial effect of water extraction of Salvadora persica (Miswak) as root canal irrigant. Al-Rafidain Dent J. 2005;5:33–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Sabawi NA, Al-Sheikh AK, Taha MY. The antimicrobial activity of Salvadora persica solution (Miswak-siwak) as root canal irrigant (a comparative study) Univ Sharjah J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2007;4:69–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sher H, Al-yemeni MN, Wijaya L. Ethnobotanical and antibacterial potential of Salvadora persica: A well known medicinal plant in Arab and Urani system of medicine. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5:1224–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noumi E, Snoussi M, Trabelsi N, Hajlaow H, Ksouri R, Valentin E, et al. Antibacterial, anticandidal and antioxidant activities of Salvadora persica and Juglans regia L extracts. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5:4138–46. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Almas K, Al-Bagieh NH. The antimicrobial effects of bark and pulp extracts of Miswak, Salvadora persica. Biomedical Letters. 1999;60:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almas K, Skaug N, Ahmad I. An in vitro antimicrobial comparison of Miswak extract with commercially available non-alcohol mouthrinses. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]