Abstract

Breast cancer is a burden for American Indian (AI) women who have younger age at diagnosis and higher stage of disease. Rural areas also have had less access to screening mammography. An Indian Health Service Mobile Women’s Health Unit (MWHU) was implemented to improve mammogram screening of AI women in the Northern Plains. Our purpose was to determine the past adherence to screening mammography at a woman’s first presentation to the MWHU for mammogram screening. Date of the most recent prior non-MWHU mammogram was obtained from mammography records. Adherence to screening guidelines was defined as the prior mammogram occurring 1–2 years before the first MWHU visit among women ≥41 years, and was the main outcome, whereas, age and clinic site were predictors. Adherence was compared with national data of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC). Among 1,771 women ≥41 years, adherence to screening mammography guidelines was 48.01 % among ≥65 years, 42.05 % among 50–64 years, 33.43 % among 41–49 years, and varied with clinic site (25.23–65.93 %). Age (p <0.0001) and clinic site (p <0.0001) were associated with adherence. Overall, adherence to screening mammography guidelines was found in 39.86 % (706/1771) of MWHU women versus 74.34 % (747,095/1,004,943) of BCSC women. The majority (60.14 %) of women at first presentation to the MWHU had not had mammograms in the previous 2 years, lower screening adherence than nationally (25.66 %). Adherence was lowest among women ages 41–49, and varied with clinic site. Findings suggest disparities in mammography screening among these women.

Keywords: Screening mammography, Health mobile, American Indians, Mammography adherence, Health disparities

Introduction

Breast cancer is a major health concern for women in the United States with 226,870 new cases and 39,510 attributable deaths estimated for 2012 [1]. Breast cancer mortality rates have declined in the last 20 years, but not all racial groups have equally benefitted from this change. American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) women have been more likely than non-Hispanic White (NHW) women to be diagnosed with later-stage breast tumors and experience a higher risk of mortality [2–5]. The mean age of diagnosis for AI/AN women is 10 years younger than NHW women (53.5 vs. 63.4 years, respectively), a difference that may reflect the younger age distributions of the AI/AN population compared to the older NHW population [4]. However, these trends are not fully understood [4–10].

Mammography allows for early detection of breast cancer, leading to lower mortality rates and reduced costs associated with treatment [11–13]. However, AI/AN women have had the lowest mammography screening rates in the United States [14, 15] and are less likely than NHW women to adhere to the follow-up guidelines [16]. Disparities exist in mammogram screening for rural women in the United States, many of whom are AI/AN [14, 17]. Lower screening rates in rural areas may relate to longer distance for access [18].

There is regional variability in breast cancer incidence among AI/ANs, and AI women of the Northern Plains region have a higher incidence of breast cancer than other regions. In these women, the proportion that is diagnosed with a breast cancer at<50 years is 1.5 times that of NHW women [4, 19]. In addition, the Northern Plains AI women have lower rates of mammography screening than NHW women in this area and among AIs nationally [19–21]. Mobile mammography units have been used since the 1980s to increase access to mammography screening, but no studies have reported data about AI women and mobile mammography.

In 2006, the Aberdeen Area Indian Health Service initiated a mobile mammography unit (Indian Health Service Mobile Women’s Health Unit—MWHU) equipped with digital mammography and satellite transmission http://www.ihs.gov/aberdeen/index.cfm?module=ab_ao_programs_mwhu. Up to that time, most Indian Health Service (IHS) clinics did not have fixed mammography units. Implementing the MWHU was aimed to improve access to screening mammography in this large Northern Plains region. Our purpose was to determine the past adherence to screening mammography at a woman’s first presentation to the MWHU for mammogram screening.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study was Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant, approved with waiver of patient consent and deemed minimal risk by the University of Michigan and the Aberdeen Area Indian Health Institutional Review Boards.

The MWHU visited 18 IHS rural and small-urban clinic sites up to 800 miles apart among reservations in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Iowa. Telemammography was performed by transmitting digital mammogram images via satellite and internet to the University of Michigan Breast Imaging Center. All IHS eligible women were candidates for screening at the MWHU and were referred by providers, with scheduled appointments. The schedule of the MWHU varied, with some clinics receiving more visits or more days than other sites, due to factors such as function of the truck, personnel, adequate patient scheduling, weather, and efficient travel. The MWHU was in service from 2006 to 2009.

We retrospectively reviewed the mammogram records of women who had screening mammography at the MWHU to determine dates of the prior outside mammogram, i.e., before the patient presented to the MWHU for mammography. The mammogram records from the first year of service, 2006, were limited, and did not have patient information forms for the majority of women, because only patients who had incomplete (BI-RADS-0) mammogram reports had had the patient information sheets retained in the mammogram record. Therefore, the women of 2006 with normal mammograms did not have the information about prior mammography. Consequently, we selected the women of 2007–2009 for full retrospective review because all of these women had patient information forms which had been retained in the mammogram record.

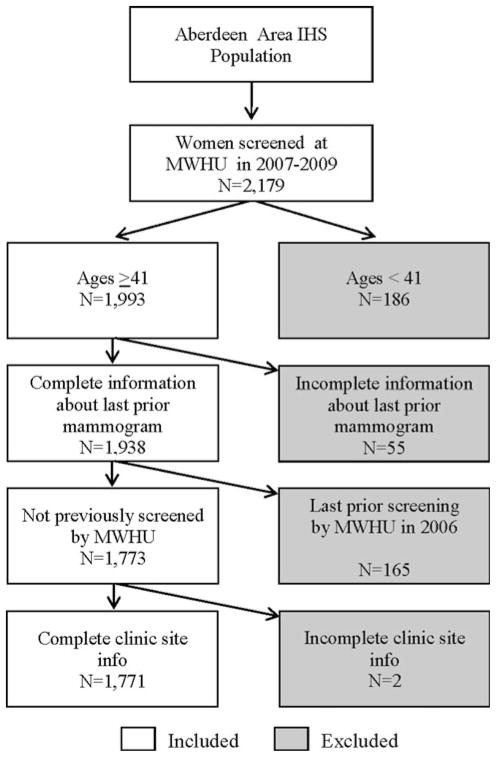

From these, the information about date of prior mammography and clinic locations of the MWHU were obtained from the mammogram records. Patient age at first MWHU visit, responses regarding prior mammography, and dates of visits to the MWHU were recorded into an EXCEL spreadsheet. Patient responses to prior mammograms or date of last prior mammogram that were ambiguous, including “1 year ago?”, “2 years ago?”, or “2–3 years ago”, or dates indicating a mammogram less than 1 year ago were categorized as “uncertain” and were excluded from final analysis. Of the women in 2007–2009, some had their last prior mammogram at the MWHU in 2006. These patients were excluded from analysis because our purpose was to evaluate the women whose last prior mammogram was “outside” the MWHU, i.e., mammogram screening adherence that existed before the patient’s first visit to the MWHU. To analyze past screening adherence, we selected women ages ≥41 years with complete prior non-MWHU mammogram information and MWHU clinic site location. Figure 1 outlines the exclusion and inclusion criteria applied. In total there were 2,179 women who presented to the Aberdeen area MWHU between 2007 and 2009. Those excluded were 186 women <age 41 (younger than screening age), 55 with incomplete mammogram information, and 165 whose last prior mammogram was not “outside” but was at the MWHU in 2006, and 2 that had incomplete clinic site information.

Fig. 1.

Patient inclusion criteria

Adherence to screening guidelines was defined as the prior mammogram occurring 1–2 years before the first MWHU visit. This time interval is consistent with the screening guidelines set forth by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which were in effect during the study time period [22]. Responses to date of prior mammogram, which were either “1 year ago”, “2 years ago”, “1–2 years ago” or a date that was within 1–2 years of their MWHU visit were categorized as adherent. Those who reported never having a previous mammogram or whose previous mammogram date was more than 2 years ago were categorized as “nonadherent.” Responses to date of last prior mammogram, which were blank or with only question marks were counted as nonadherent. These criteria are similar to those previously published and described as “on schedule repeat mammography” [23]. The variables used for final analysis were the patient age, previous mammogram status (yes, no, unknown), time since last prior non-MWHU mammogram, and first MWHU clinic site.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were generated for all women who presented at the MWHU in 2007–2009 (N = 2,179) and also only for those ages ≥41 with complete MWHU clinic site and prior mammogram information with no record of a 2006 MWHU visit as the final sample (N = 1,771). Adherence to mammogram guidelines was the main outcome variable whereas age group (41–49, 50–64, and 65+) and MWHU clinic site were the predictor variables. The χ2 test was applied to asses for statistically significant differences between women considered “adherent” and “nonadherent” among age groups and MWHU clinic sites. Logistic regression was used to assess the relationship among adherence status, age group, and MWHU clinic site adjusting for both predictors. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated. To calculate the AOR for first visit clinic site, the clinic site with the median percentage of women adherent was defined as the reference group. Although there were two clinic sites with median levels of adherence (Flandreau, SD and New Town, ND) due to the even number of clinic sites, New Town was arbitrarily chosen as the reference group. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and the database was compiled using Microsoft Excel 2010.

To benchmark our data, national mammogram data of the same years 2007–2009 for comparison was obtained from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) Research Resource, a national mammography registry supported by the National Cancer Institute which collects mammographic and demographic information from women undergoing mammography from seven registries of various community-based facilities. More information regarding this resource is available at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/[24].

We requested from this registry and they provided data of screening mammography among women ages ≥41 years who had prior screening 1–2 years previously. The BCSC excluded patients with missing data, those who had no information about prior mammography or a missing date since the prior mammogram. These adjustments all coincided with our methods, thereby making them comparable.

Results

Table 1 summarizes all 2,179 women who presented to the Aberdeen area MWHU for mammography between 2007 and 2009, ages 23–91 years (mean = 53.27 year). The largest subgroup by age was the 50–64 age group (42.59 %) and the fewest women were in the <41 age group (8.53 %). Nearly all women knew whether they had a previous mammogram or not (99.59 %). 84.49 % of women reported having had a prior mammogram.

Table 1.

All women having screening mammograms at the Aberdeen Area Women’s Mobile Health Unit (MWHU) during 2007–2009

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 53.27 (10.44) | 23–91 |

|

| ||

| N (number of women) | % | |

| Age group (years) | ||

| <41 | 186 | 8.53 |

| 41–49a | 723 | 36.39 |

| 50–64a | 928 | 42.59 |

| 65+a | 342 | 15.70 |

| Previous mammogram? | ||

| Yes | 1841 | 84.49 |

| No | 329 | 15.10 |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.41 |

| Previously adherent to mammography guidelines?b | ||

| Yes | 706 | 32.40 |

| No | 665 | 30.52 |

| Uncertain | 55 | 2.52 |

| Without evidence of adherence | 402 | 18.45 |

| Not applicable (age <41 years) | 186 | 8.53 |

| Not applicable (ages 41+ with last prior screening at MWHU 2006) | 165 | 7.57 |

| Clinic site (2007–2009) | ||

| Belcourt | 254 | 11.66 |

| Fort Yates | 184 | 8.44 |

| Fort Thompson | 166 | 7.62 |

| Wagner | 154 | 7.07 |

| Winnebago | 148 | 6.79 |

| Trenton | 133 | 6.10 |

| Eagle Butte | 128 | 5.87 |

| Macy | 120 | 5.51 |

| Wanblee | 117 | 5.37 |

| New Town | 117 | 5.37 |

| McLaughlin | 116 | 5.32 |

| Kyle | 108 | 4.96 |

| Pierre | 107 | 4.91 |

| Flandreau | 86 | 3.95 |

| Lower Brule | 83 | 3.81 |

| Tama | 76 | 3.49 |

| Aberdeen | 54 | 2.48 |

| Niobrara | 26 | 1.19 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.09 |

N = 2,179

Age group recommended for screening mammography

Adherence defined as reporting last previous mammogram 1–2 years prior for women ages 41+ years, based on U.S. Preventative Services Task Force Guidelines effective during study period years

Table 2 summarizes the final sample of 1,771 women of those eligible for screening at age ≥41 having prior mammogram information. Adherence to screening mammography guidelines was found in 39.86 % of patients, and 12.42 % had no prior mammograms. The number of women at each clinic site ranged from 254 women at Belcourt, ND (Turtle Mountain Reservation) to 26 at Niobrara, NE (Santee Sioux Nation).

Table 2.

Women having screening mammograms ages ≥41 years with prior mammogram and clinic site information (N = 1,771)

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 54.64 (9.90) | 41–91 |

|

| ||

| N (number of women) | % | |

| Age group | ||

| 41–49 | 658 | 37.15 |

| 50–64 | 811 | 45.79 |

| 65+ | 302 | 17.05 |

| Previous mammogram? | ||

| Yes | 1,551 | 87.58 |

| No | 220 | 12.42 |

| Evidence of adherence to mammography guidelinesa | ||

| Yes | 706 | 39.86 |

| No | 1,065 | 60.14 |

| First MWHU visit clinic site | ||

| Belcourt | 217 | 12.25 |

| Wagner | 137 | 7.74 |

| Winnebago | 136 | 7.68 |

| Ft. Yates | 108 | 6.10 |

| Ft. Thompson | 117 | 6.61 |

| Eagle Butte | 111 | 6.27 |

| Wanblee | 107 | 6.04 |

| Macy | 106 | 5.99 |

| Newtown | 98 | 5.53 |

| Kyle | 98 | 5.53 |

| Trenton | 91 | 5.14 |

| Pierre | 85 | 4.80 |

| McLaughlin | 76 | 4.29 |

| Flandreau | 75 | 4.23 |

| Lower Brule | 72 | 4.07 |

| Tama | 63 | 3.56 |

| Aberdeen | 49 | 2.77 |

| Niobrara | 25 | 1.41 |

Adherence defined as reporting last previous mammogram 1–2 years prior for women ages 41+ years, based on U.S. Preventative Services Task Force Guidelines effective during study period years

Table 3 compares adherent with nonadherent groups by age and clinic site. The bivariate analysis shows that both age (χ2 = 24.32, p <0.0001) and first MWHU clinic site (χ2 = 101.38, p <0.0001) were significantly associated with adherence status in χ2 analysis at the 0.05 level of significance. The proportion of women adherent to screening increased with older age groups, i.e., for ages 41–49, 33.43 % were adherent versus 48.01 % of those ages 65+. Adherence also varied by clinic site. Those sites with over 50 % adherence included Trenton, ND (65.93 %), Ft. Thompson, SD (53.85 %), Eagle Butte, SD (63.96 %) and Niobrara, NE (64 %). The remaining clinic sites had adherence that ranged from 42.86 % (Kyle, SD) to 25.23 % (Wanblee, SD).

Table 3.

Adherent versus nonadherent groups from Table 2, by age and clinic site

| Adherent

|

Nonadherent

|

χ2 | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Age (years) | 24.32 | <0.0001* | ||||

| 41–49 | 220 | 33.43 | 438 | 66.57 | ||

| 50–64 | 341 | 42.05 | 470 | 57.95 | ||

| 65+ | 145 | 48.01 | 157 | 51.99 | ||

| First MWHU visit clinic site | 101.3882 | <0.0001* | ||||

| Belcourt | 87 | 40.09 | 130 | 59.91 | ||

| Wagner | 58 | 42.34 | 79 | 57.66 | ||

| Winnebago | 41 | 30.15 | 95 | 69.85 | ||

| Ft. Yates | 34 | 31.48 | 74 | 68.52 | ||

| Ft. Thompson | 63 | 53.85 | 54 | 46.15 | ||

| Eagle Butte | 71 | 63.96 | 40 | 36.04 | ||

| Wanblee | 27 | 25.23 | 80 | 74.77 | ||

| Macy | 32 | 30.19 | 74 | 69.81 | ||

| Newtown | 37 | 37.76 | 61 | 62.24 | ||

| Kyle | 42 | 42.86 | 56 | 57.14 | ||

| Trenton | 60 | 65.93 | 31 | 34.07 | ||

| Pierre | 28 | 32.94 | 57 | 67.06 | ||

| McLaughlin | 22 | 28.95 | 54 | 71.05 | ||

| Flandreau | 26 | 34.67 | 49 | 65.33 | ||

| Tama | 20 | 31.75 | 43 | 68.25 | ||

| Lower Brule | 23 | 31.94 | 49 | 68.06 | ||

| Aberdeen | 19 | 38.78 | 30 | 61.22 | ||

| Niobrara | 16 | 64.00 | 9 | 36.00 | ||

N = 1,771

Statistically significant

Table 4 demonstrates the multivariate analysis, using logistic regression to test for a relationship between one predictor and adherence status while controlling for the other predictor. When adjusting for clinic site, those in the 41–49 age group had 35 % lower odds of previous mammogram guideline adherence as compared to women in the 65+ age group (AOR = 0.65, 95 % CI = 0.482, 0.874). The AOR for women ages 50–64 compared to women ages 65+ was not statistically significant. There were five clinics with significant AORs. Four sites had greater odds of adherence as compared to the median level including Ft. Thompson (AOR = 1.961, 95 % CI = 1.132, 3.397) Trenton (AOR = 3.193, 95 % CI = 1.755, 5.810), Niobrara (2.958, 95 % CI = (1.182, 7.402), and Eagle Butte (AOR = 2.727, 95 % CI = 1.538, 4.836). The Wanblee site (AOR = 0.546, 95 % CI = 0.299, 0.994) had lower odds of adherence.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratio and 95 % confidence interval from logistic regression of adherence to mammography guidelines among women ages 41+ years

| Model 1

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Adherent

|

||

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95 % confidence interval | |

| Age | ||

| 41–49 | 0.649 | (0.482, 0.874)* |

| 50–64 | 0.954 | (0.717, 1.270) |

| 65+ | Reference | Reference |

| First MWHU visit clinic site | ||

| Belcourt | 1.094 | (0.551, 2.279) |

| Ft. Yates | 0.785 | (0.440, 1.400) |

| Wagner | 1.199 | (0.704, 2.043) |

| Trenton | 3.193 | (1.755, 5.810)* |

| Newtown | Reference | Reference |

| Winnebago | 0.697 | (0.401, 1.209) |

| Ft. Thompson | 1.961 | (1.132, 3.397)* |

| McLaughlin | 0.684 | (0.358, 1.304) |

| Eagle Butte | 2.727 | (1.538, 4.836)* |

| Macy | 0.723 | (0.403, 1.297) |

| Wanblee | 0.546 | (0.299, 0.994)* |

| Pierre | 0.820 | (0.444, 1.512) |

| Kyle | 1.224 | (0.690, 2.174) |

| Flandreau | 0.896 | (0.477, 1.682) |

| Tama | 0.778 | (0.397, 1.524) |

| Lower Brule | 0.830 | (0.477, 1.682) |

| Aberdeen | 1.121 | (0.551, 2.279) |

| Niobrara | 2.958 | (1.182, 7.402)* |

Statistically significant at 0.05 level

Table 5 compares the mammogram adherence of the MWHU women to 1,004,943 total women in the BCSC of age ≥41 years during same time period. Of MWHU women, 39.86 % were adherent, which is lower than the AI/AN women in the BCSC data (59.83 %), and much lower than of the BCSC white women (77.65 %) or all BCSC women (74.34 %). No prior mammograms were reported among 12.42 % of MWHU women, lower than the AI/AN women in the BCSC data (17.23 %), but higher than that of BCSC white women (6.29 %).

Table 5.

Adherence to screening mammography guidelines, women ≥41 years: American Indian women of the MWHU compared to women of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium

| Adherence to mammography guidelines | MWHUb (n = 1,771) | BCSC

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI/AN (n = 3,122) | White (n = 732,719) | All ethnicities (n = 1,004,943) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Yesa | 706 | 39.86 | 1,868 | 59.83 | 568,976 | 77.65 | 747,095 | 74.34 |

| No prior mammogram | 220 | 12.42 | 538 | 17.23 | 46,100 | 6.29 | 83,031 | 8.26 |

Last prior mammogram 1–2 years ago

See Table 2

Discussion

We report the past screening mammogram adherence at the time AI women came to the MWHU for screening. Before presenting to the MWHU, the majority of these women had not had a prior mammogram in the previous 2 years, although most (~87 %) had some prior mammography. Adherence to screening varied by patient age and by clinic site. Adherence to screening increased with older age, with those in the 41–49 age group having lower odds of mammogram screening adherence than those in the 65+ age group. Overall, as compared with national data, AI women had a much lower rate of mammogram adherence (39.86 %) versus the BCSC white women subgroup (77.65 %), or the BCSC AI/AN subgroup (59.83 %). Of MWHU AI women, 12.42 % had no prior mammograms, somewhat similar but lower than the AI/AN subgroup of the BCSC (17.23 %), but twice as high as the BCSC white women subgroup (6.29 %). The reason for these disparities could be related to rural location and less access to mammogram screening.

National mammography screening estimates are commonly based on self-reported telephone surveys such as the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System [25]. However, women at the MWHU were self-selected, i.e., those who present for screening mammography, our data are not directly comparable to the BRFSS which can estimate prevalence of mammography in an entire population, nor the IHS Government Performance and Review Act data which are based on IHS medical records in one selected age group [20, 25]. The MWHU data are more comparable to data of the BCSC, a national mammography registry of the National Cancer Institute which collects mammographic and demographic information from women undergoing mammography from seven registries of various community based facilities [24].

Similar to other studies, we found that younger women were less likely to be adherent to mammography screening guidelines than older women [17, 26–28]. This also reflects national BRFSS data indicating that older woman are more likely to have had mammograms with the highest prevalence of mammography use within 2 years among those aged 60–69 years (81.3 %) and 70–74 years (82.4 %) [29]. Reasons for this difference may relate to patient and physician confusion about which age to start screening, since there has been much controversy over the years about the benefits of mammography for women ages 40–49 [30]. Multiple organizations recommend that routine mammography screening begin at age 40, although there are still differing opinions regarding the intervals, of 1 versus 2 years. Although previous studies report that a higher proportion of AI women are diagnosed with breast cancer at age <50 than white women, the AI women in the 41–49 age group had the lowest screening adherence of the three age groups [4].

Among clinic sites, adherence ranged from 65.93 to 25.23 %; four had a significantly greater proportion of women (54–66 %) that were adherent to screening guidelines than the median level of adherence, with one site showing the opposite. There did not appear to be any geographic pattern to adherence differences by clinic site. The four sites with higher than average adherence were in northwestern North Dakota, central South Dakota (two sites), and northern Nebraska. Three of the 18 clinic sites had screening adherence of ≥60 %, similar or higher than the BCSC AI/AN rate. Differences between clinics may reflect previous availability of mammography from fixed mammography facilities at some IHS clinics or intermittent screening programs from mobile units from regional non-IHS health centers.

Nationwide, AI/AN women have the lowest mammography screening rates in the United States [14, 15], and although IHS data shows an upward screening trend, IHS rates are lower than national rates. In 2011, the IHS reached their goal of at least biennial screening for 49.6 % of all AI/AN women ages 52–64, much lower than national screening rates [20, 31]. Region-specific studies are important for AI/AN populations due to the uniqueness of the culture and the variable regional incidence of breast cancer among AI/AN women [4]. Based on IHS data, the Aberdeen Area has slightly lower rates of mammography among women ages 52–64 than all IHS areas combined (43.3 vs. 49.8 % in 2011, unchanged since 2008) [20]. Based on BRFSS data, fewer AI/AN women receive mammograms in the prior 2 years than white women [26, 29]. A study of mammography adherence in AI women in Colorado found an odds of annual mammography 0.5 times that of NHW women [16]. Mammography screening varies greatly among IHS regions [17, 19], with AI women in the Eastern U.S. having higher screening mammography rates (72.7 %) compared to those in the Southwest (62.2 %). AI women in every IHS region had mammography rates lower than NHW women (76.2 %) [19].

Many factors affect mammography screening adherence in AI women. In the Northern Plains region, a recommendation for mammography from a healthcare provider was the only significant predictor for having received a mammogram [32], whereas another study in Colorado found annual household income and a family history of breast cancer to correspond with mammography adherence [16]. AI women from a specific reservation in the Northern Plains who had not had a mammogram in the previous year were less likely to know that older women had a higher breast cancer risk, less likely to have a mammogram even if recommended by a healthcare provider, and less willing to travel long distances to receive screening. These negative views might coincide with a chronic distrust in the healthcare system observed among many AI/AN populations [33]. No single solution to increase mammography screening exists for all AI/AN individuals, and differences among regions and tribes need to be considered [32].

Our study makes a contribution to the scarce literature about AI/AN women, screening adherence, and the significance of mobile mammography in rural areas. The patient sample group represents a large-geographic area. There were limitations to our study. The study group is small, and is a selected group because it is women who chose to come for screening mammography. Therefore these women are more likely to have been adherent to mammogram screening. For example, about 85 % of these women reported having ever had a mammogram, which is substantially higher than a cancer screening study reported by Pandhi, wherein only 51 % of a sample of women in the Northern Plains reported ever having had any kind of breast cancer screening (mammography or clinical examination) [32]. In addition, the mobile unit was only intermittently available, and not equally available to all clinics which may result in some selection bias among the clinic sites.

In conclusion, the majority (60.14 %) of women at first presentation to the MWHU had not had mammograms in the previous 2 years, which was lower adherence to screening than national rates (25.66 %). Adherence was lowest among women ages 41–49, and varied with clinic site. Findings suggest health disparities and importance of mobile mammography. Continued efforts to provide mobile mammography to these women and greater focus in certain IHS clinic locations that may help change these screening mammography disparities.

Acknowledgments

R25CA112383 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Data collection and sharing was supported by the National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA8602, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA70040, HHSN261201100031C). A list of the BCSC investigators and procedures for requesting BCSC data for research purposes are provided at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/. Spirit of Eagles U54-CA153605-01.

Abbreviations

- AAIHS

Aberdeen Area Indian Health Service

- AI

American Indian

- AI/AN

American Indian/Alaska Native

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- BCSC

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium

- BI-RADS

American College of Radiology Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System®

- BRFSS

Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System

- GPRA

Government Performance and Review Act

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- IHS

Indian Health Service

- MWHU

Indian Health Service Mobile Women’s Health Unit

- NHW

Non-Hispanic White

- USPSTF

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

- UMHS

University of Michigan Health System

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Drs. Roubidoux and Joe were part of nine radiologist group at the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) who interpreted the mammograms for the Mobile Women’s Health Unit, under a contract for mammography services between the UMHS and the Aberdeen Area Indian Health Service (AAIHS). Tina R. Russell was employed by AAIHS. Manuscript was approved by the AAIHS Internal Review Board on Jan 18, 2013.

Contributor Information

Emily L. Roen, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029, USA

Marilyn A. Roubidoux, Email: roubidou@umich.edu, Division of Breast Imaging, Department of Radiology, University of Michigan Medical School, 2910H Taubman Center, SPC 5326, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA

Annette I. Joe, Division of Breast Imaging, Department of Radiology, University of Michigan Medical School, 2910H Taubman Center, SPC 5326, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA

Tina R. Russell, Midwest Division, Community Partnerships of South Dakota, American Cancer Society, Inc., Sioux Falls, SD, USA

Amr S. Soliman, Department of Epidemiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute (NCI) SEER Cancer statistics review 1975–2009. [Accessed 2 Aug 2012];Estimated new cancer cases and deaths for 2012: all races, by sex. 2012 http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/results_single/sect_01_table.01.pdf.

- 2.Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman SC, Breen N, Davis WW, Reichman MC. Trends in area-socioeconomic and race-ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, screening, mortality, and survival among women ages 50 years and over (1987–2005) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):121–131. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR. Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wingo PA, King J, Swan J, Coughlin SS, Kaur JS, Erb-Alvarez JA, Jackson-Thompson J, Arambula Solomon TG. Breast cancer incidence among American Indian and Alaska Native women: US, 1999–2004. Cancer. 2008;113(5 Suppl):1191–1202. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, Chu K, Edwards BK. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (surveillance, epidemiology, and end results) Program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(17):1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amey CH, Miller MK, Albrecht SL. The role of race and residence in determining stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. J Rural Health. 1997;13(2):99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1997.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry J, Breen N. The importance of place of residence in predicting late-stage diagnosis of breast or cervical cancer. Health Place. 2005;11(1):15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee-Feldstein A, Feldstein PJ, Buchmueller T, Katterhagen G. The relationship of HMOs, health insurance, and delivery systems to breast cancer outcomes. Med Care. 2000;38(7):705–718. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menck HR, Mills PK. The influence of urbanization, age, ethnicity, and income on the early diagnosis of breast carcinoma: opportunity for screening improvement. Cancer. 2001;92(5):1299–1304. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1299::aid-cncr1451>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taplin SH, Ichikawa L, Yood MU, Manos MM, Geiger AM, Weinmann S, Gilbert J, Mouchawar J, Leyden WA, Altaras R, et al. Reason for late-stage breast cancer: absence of screening or detection, or breakdown in follow-up? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(20):1518–1527. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kauhava L, Immonen-Raiha P, Parvinen I, Holli K, Kronqvist P, Pylkkanen L, Helenius H, Kaljonen A, Rasanen O, Klemi PJ. Population-based mammography screening results in substantial savings in treatment costs for fatal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98(2):143–150. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopans DB. Screening for Breast Cancer. In: Williams L Wilkins., editor. Breast imaging. 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 121–190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickson C, Mason KE, English DR, Kavanagh AM. Mammographic Screening and breast cancer mortality: a case–control study and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(9):1479–1488. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peek ME, Han JH. Disparities in screening mammography. Current status, interventions and implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, Abraham L, Barbash RB, Strzelczyk J, Dignan M, Barlow WE, Beasley CM, Kerlikowske K. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):541–553. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wampler NS, Saba L, Rahman SM, Dignan M, Voeks JH, Strzelczyk J. Factors associated with adherence to recommendations for screening mammography among American Indian women in Colorado. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):808–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher MC, Slattery ML, Lanier AP, Ma KN, Edwards S, Ferucci ED, Tom-Orme L. Prevalence and predictors of cancer screening among American Indian and Alaska native people: the EARTH study. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(7):725–737. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan L, Mohile S, Zhang N, Fiscella K, Noyes K. Self-reported cancer screening among elderly Medicare beneficiaries: a rural–urban comparison. J Rural Health. 2012;28(3):312–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espey DK, Wu XC, Swan J, Wiggins C, Jim MA, Ward E, Wingo PA, Howe HL, Ries LA, Miller BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2119–2152. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Indian Health Service (IHS) Quality of IHS health care. [Accessed 2 Aug 2012];Performance measures: cancer screening—breast (mammography) 2012 http://www.ihs.gov/qualityofcare/index.cfm?module=chart&rpt_type=gpra&measure=16.

- 21.Watanabe-Galloway S, Flom N, Xu L, Duran T, Frerichs L, Kennedy F, Smith CB, Jaiyeola AO. Cancer-related disparities and opportunities for intervention in Northern Plains American Indian communities. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(3):318–329. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) [Accessed 2 Aug 2012];Screening for breast cancer 2002. 2002 http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsbrca2002.htm.

- 23.Rakowski W, Meissner H, Vernon SW, Breen N, Rimer B, Clark MA. Correlates of repeat and recent mammography for women ages 45 to 75 in the 2002 to 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2093–2101. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, Ernster VL, Rosenberg RD, Carney PA, Barlow WE, Geller BM, Kerlikowske K, Edwards BK, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: a national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(4):1001–1008. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cronin KA, Miglioretti DL, Krapcho M, Yu B, Geller BM, Carney PA, Onega T, Feuer EJ, Breen N, Ballard-Barbash R. Bias associated with self-report of prior screening mammography. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1699–1705. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: breast cancer screening among women aged 50–74 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(26):813–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanier AP, Kelly JJ, Holck P. Pap prevalence and cervical cancer prevention among Alaska Native women. Health Care Women Int. 1999;20(5):471–486. doi: 10.1080/073993399245566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vyas A, Madhavan S, LeMasters T, Atkins E, Gainor S, Kennedy S, Kelly K, Vona-Davis L, Remick S. Factors influencing adherence to mammography screening guidelines in Appalachian women participating in a mobile mammography program. J Community Health. 2012;37(3):632–646. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9494-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morbidity and mortality weekly report (MMWR): breast cancer screening among adult women. [Accessed 17 Oct 2012];Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS), United States, 2010. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6102a8.htm#tab1.

- 30.Roubidoux MA. Breast cancer and screening in American Indian and Alaska Native women. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(Suppl 1):S66–S72. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. [Accessed 2 Aug 2012];Healthy people 2020 summary of objectives: Cancer. 2012 http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/Cancer.pdf.

- 32.Pandhi N, Guadagnolo BA, Kanekar S, Petereit DG, Smith MA. Cancer screening in Native Americans from the Northern Plains. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wampler NS, Ryschon T, Manson SM, Buchwald D. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding breast cancer among American Indian women from the Northern Plains. J Appl Gerontol. 2006;25(1 Suppl):44S–59S. [Google Scholar]