Abstract

The centromere is the chromosomal locus that ensures fidelity in genome transmission at cell division. Centromere protein A (CENP-A) is a histone H3 variant that specifies centromere location independently of DNA sequence. Conflicting evidence has emerged regarding the histone composition and stoichiometry of CENP-A nucleosomes. Here we show that the predominant form of the CENP-A particle at human centromeres is an octameric nucleosome. CENP-A nucleosomes are very highly phased on α-satellite 171 bp monomers at normal centromeres, and also display strong positioning at neocentromeres. At either type of functional centromere, CENP-A nucleosomes exhibit similar DNA wrapping behavior as octameric CENP-A nucleosomes reconstituted with recombinant components, having looser DNA termini than those on their conventional counterparts containing canonical H3. Thus, the fundamental unit of the chromatin that epigenetically specifies centromere location in mammals is an octameric nucleosome with loose termini.

Faithful genome inheritance at cell division requires that each chromosome contain a single functional centromere1. The centromere is the site of assembly of the mitotic kinetochore—a massive complex of proteins that serves as the connection point to the microtubule-based spindle— and also serves as the site of final sister chromatid cohesion1. Strong evidence suggests that CENP-A can provide the key epigenetic information to mark centromere location2–4, distinguishing centromeres from the rest of the chromosome. Prime examples of the DNA sequence-independent nature of centromere inheritance are human neocentromeres that have been isolated out of the population, where centromere function is uncoupled from the repetitive α-satellite DNA that typically overlaps with CENP-A chromatin occupancy5–10. Fundamental questions remain regarding CENP-A nucleosomes, such as the histone composition and stoichiometry of the CENP-A particle and how much DNA it wraps.

There is now nearly a consensus on the point that recombinant, purified CENP-A readily assembles into octameric nucleosomes where two copies of CENP-A replace the two copies of canonical H311–15. Reconstituted octameric CENP-A nucleosomes are known to have loose terminal DNA contacts13,15,16. In addition to loose terminal DNA wrapping, the CENP-A targeting domain (CATD) confers structural changes14,15, as well as conformational rigidity14,17, to the folded core of reconstituted octameric nucleosomes. The relevance of all studies of recombinant nucleosomes to native centromeric chromatin is unclear, however, because the field remains deeply divided over key issues on the nature of the protein–DNA particle into which CENP-A assembles in vivo18. Experiments involving isolation of CENP-A particles from various eukaryotic species have led to radically different models for the fundamental unit of centromeric chromatin including non-octameric forms (e.g. tetrasomes19, hemisomes20–23, hexasomes24, etc.). Perhaps the two most intriguing and conflicting proposals for the major form of the CENP-A particles that specify centromere location in metazoans are for octameric nucleosomes and hemisomes. The two proposals suggest radically different modes for how centromere-specifying chromatin particles are distinguished from bulk nucleosomes. Clear examples of when such molecular recognition is important at the centromere include the direct binding of CENP-A-containing particles by constitutive non-histone centromere components, CENP-N4,25 and CENP-C4,26.

To test the proposed models for the major form of the fundamental repeating unit of centromeric chromatin, we used native chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-Seq) of CENP-A-containing particles from normal centromeres on α-satellite DNA and three naturally-occurring neocentromeres.

Results

CENP-A particles protect ~100–150 bp from MNase digestion

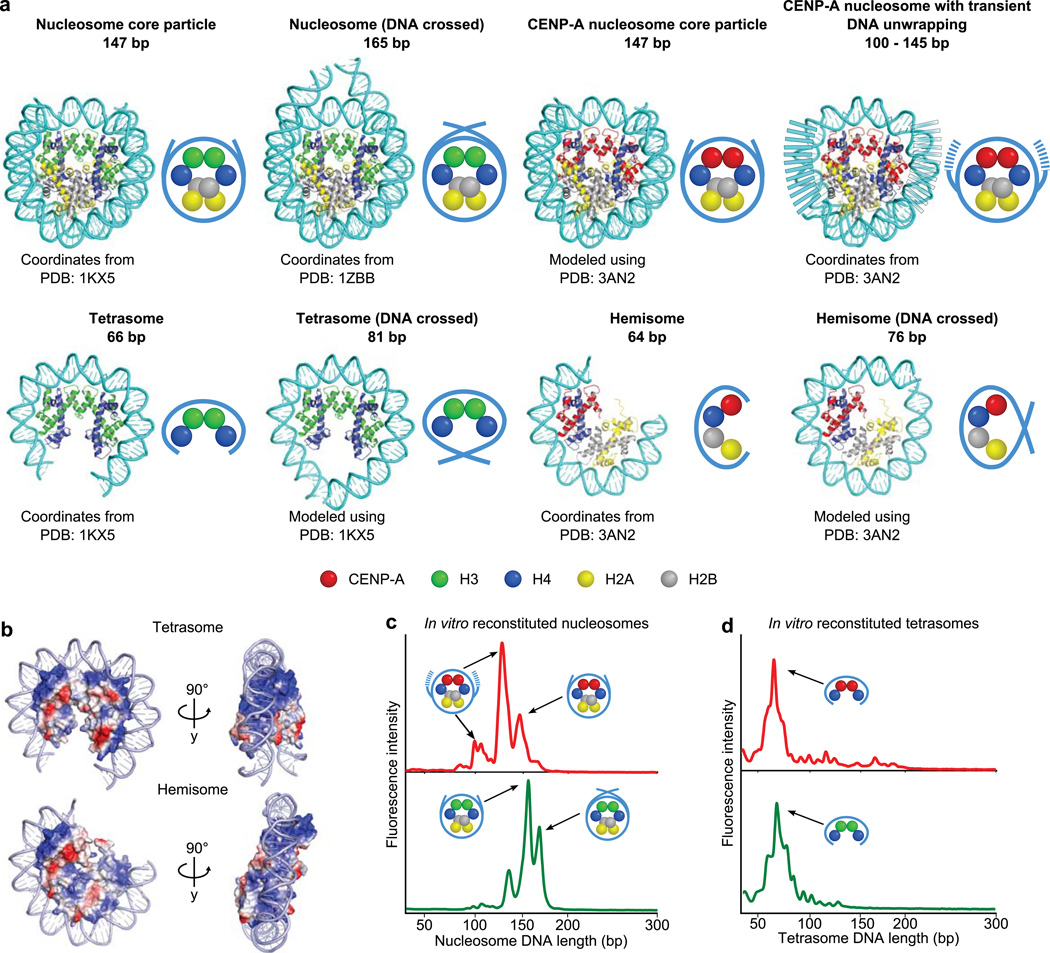

To investigate the nature of CENP-A-containing particles at functional human centromeres, we first considered the merits of a micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion approach coupled to ChIP-Seq. The MNase approach is attractive because it straightforwardly tests the specific predictions for how much DNA could be wrapped by octameric nucleosomes or hemisomes (Fig. 1a)15,27. Since early nucleosome studies, MNase protection has been a standard for defining canonical nucleosomes28,29. Crystallographic studies of canonical nucleosomes have defined how each histone dimer pair (H2A–H2B or H3–H4) has a single, basic DNA binding ridge that binds to ~25–30 bp of DNA27. The canonical histone octamer wraps ~100–120 bp of DNA in this way with the final ~two turns (~20 bp) of terminal DNA stabilized by contacts with the αN helix of histone H3. Thus, in total, the canonical nucleosome core particle stably protects ~147 bp from MNase digestion. Tetrameric histone complexes of any sort only have enough DNA wrapping surface to bind to ~65 bp of DNA (Fig. 1b)30–32. Before embarking on our ChIP-Seq studies of CENP-A nucleosomes isolated from functional centromeres, we examined reconstituted CENP-A-containing complexes using one of the same high-resolution, high-sensitivity detection methods with which we now employ with the native particles (see below). We found that recombinant CENP-A nucleosomes lack protection of crossed entry–exit DNA (i.e. they do not protect a fragment corresponding to the ~165 bp peak protected by canonical nucleosomes containing conventional H3) and digest to three discrete peaks, one the size of the nucleosome core particle (~145 bp) and two of smaller size (~110 and ~130 bp)(Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). All of the fragment lengths protected by recombinant octameric CENP-A nucleosomes are substantially larger than any fragment from reconstituted (H3–H4)2 and (CENP-A–H4)2 tetrasomes that protect ~65 bp (Fig. 1d). Thus, structural models and experiments with reconstituted particles encouraged us to pursue a similar MNase strategy with native CENP-A particles to distinguish between the radically different configurations that have been proposed for the fundamental unit of functional centromeric chromatin.

Figure 1. Structure-based predictions for MNase protection and experimental outcomes with CENP-A-containing particles assembled with recombinant components.

(a) Molecular models (cartoon representations, right) of the indicated, proposed DNA–protein particles demonstrating the expected length of DNA protected following MNase digestion. (b) Electrostatic surface potential maps depicting the predicted path of DNA wrapping a CENP-A-containing tetrasome or hemisome, where positively charged surfaces are colored in blue and negatively charged surfaces are colored in red. Note that 64–66 bp completely covers the DNA wrapping surface of either tetrameric configuration. (c,d) MNase digestion profiles of octameric CENP-A- or H3-containing mononucleosomes (c) or tetrasomes (d) reconstituted on a 200 bp template.

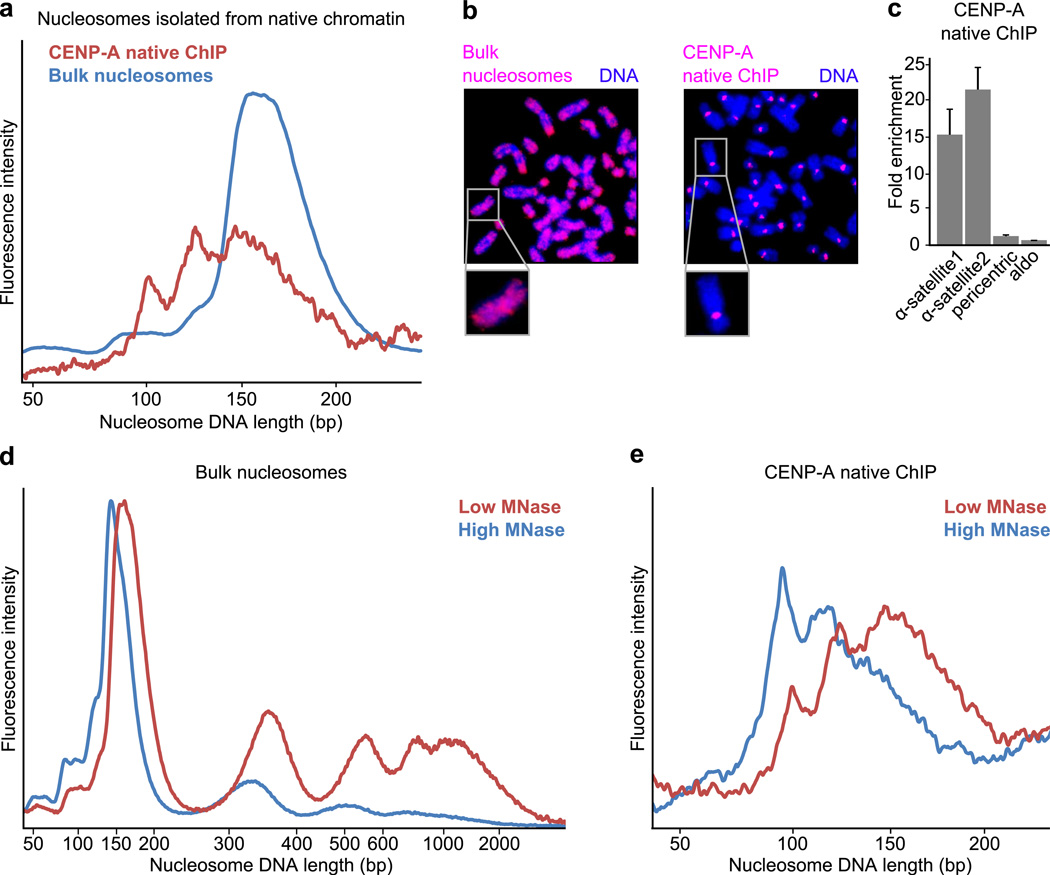

Native ChIP of CENP-A-containing particles from human cultured cells strongly enriched centromere DNA and yielded MNase-protected fragments in three major size classes (~110 bp, ~130 bp, ~150bp)(Fig. 2a–c). Native ChIP of canonical nucleosomes containing conventional H3 yielded a distribution of a single size class of MNase-protected fragments that expectedly matched the input bulk nucleosomes (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a), indicating that the smaller fragments observed for CENP-A-containing particles are not due to additional fragmentation during immunoprecipitation. If the smaller fragments (~110 bp) are derived from digestion of the nucleosome termini, as in our experiments with recombinant CENP-A octameric nucleosomes (Fig. 1c), then excessive digestion should remove the termini and leave a stable ~110 bp core fragment undigested. We tested this notion by repeating the isolation of CENP-A nucleosomes where we used a low or high concentration of MNase. Treatment with high concentration of MNase expectedly yields more heavily digested bulk chromatin with a higher mononucleosome:dinucleosome ratio and mononucleosomes that are trimmed down to core particles (Fig. 2d). High concentration MNase treatment diminishes the larger (130–160 bp fragments) and increases the smaller (100–120 bp fragments) MNase-protected DNA fragments from isolated CENP-A particles (Fig. 2e). These findings suggest that native CENP-A particles have a stable core with transiently unwrapping ends that are digested in a manner that is sensitive to the concentration of MNase.

Figure 2. Nuclease digestion of native CENP-A-containing particles resembles that of octameric nucleosomes with loose termini.

(a) DNA length distributions of MNase-digested CENP-A native ChIP and bulk nucleosomes from the same preparation. (b) Fluorescence in situ hybridization using DNA from bulk nucleosomes or CENP-A native ChIP as probes. Bulk nucleosome DNA labels the entire chromosome whereas CENP-A probe labels solely centromeric regions, as expected. (c) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis comparing enrichment of CENP-A native ChIP DNA relative to bulk nucleosome DNA. CENP-A ChIP sequences are enriched for α-satellite regions (α-satellite1, α-satellite2), but not at pericentric or promoter (aldo) regions, as expected. Error bars represent s.e.m. from three independent replicates. (d) Standard digestion (red) or overdigestion (blue, threefold higher concentration of MNase used) of chromatin. (e) DNA length distributions of CENP-A native ChIP following standard digestion (red) or overdigestion (blue) of chromatin.

Transient unwrapping of nucleosome terminal DNA predicts that chemical protein–DNA crosslinking would lock the DNA to the CENP-A-containing histone octamer. Indeed, standard formaldehyde crosslinking as is used in diverse chromatin studies33,34, yielded CENP-A-containing particles with a single distribution of MNase-protected fragments of ~150–170 bp, nearly identical to that of solubilized bulk nucleosomes (Supplementary Fig. 2b–e). These CENP-A particles were isolated out of nucleosome preparations that contained all detectable CENP-A protein (Supplementary Fig. 2b), and were specifically enriched for α-satellite DNA (Supplementary Fig. 2c) to a similar extent as were native preparations (Fig. 2c). Further, similar results were obtained for two independent cell types, one derived from healthy tissue (PD-NC4 cells) and one derived from a tumor (HeLa)(Supplementary Figs. 2d,e). Together, our findings strongly suggest that we are monitoring the DNA wrapping behavior of the major form of CENP-A nucleosomes, and that in doing so, our approach represents a highly sensitive means to probe centromere chromatin architecture.

CENP-A nucleosome positions on complex, neocentromeric DNA

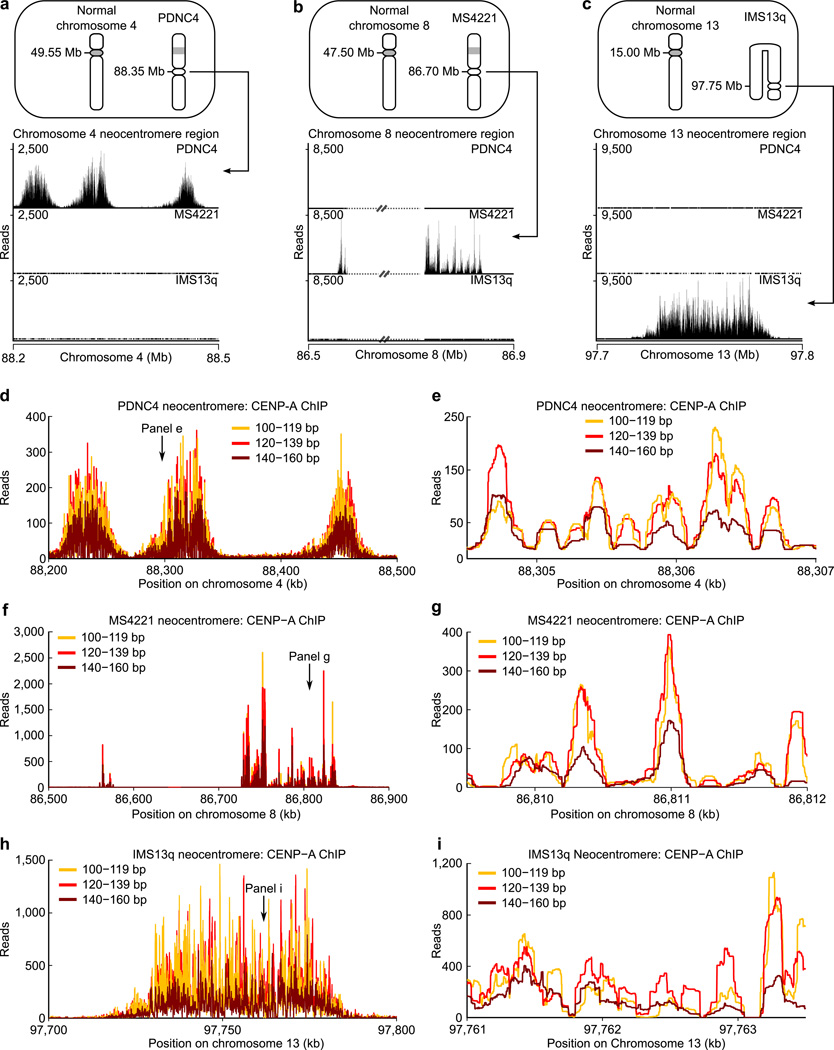

We considered that the sub-145 bp MNase-protected fragments on natively prepared CENP-A particles could be caused by 1) the physical properties conferred by the incorporation of CENP-A into nucleosomes that make the terminal DNA susceptible to MNase digestion or 2) the properties imposed by the sequence or higher-order structure of the α-satellite DNA (where the monomer repeat unit is 171 bp18,35) upon which CENP-A is assembled at normal human centromeres. Neocentromeres provide a prime tool to investigate functional CENP-A nucleosomes in the absence of any effects imposed by α-satellite DNA. We used patient-derived cell lines harboring one neocentromeric chromosome each (Fig. 3a–c) for ChIP-Seq studies. Two of the neocentromeres map to single copy, complex DNA sequences6,8 (Fig. 3a,c) while the other is present on a repeat sequence where the ~12 kb monomer sequence is completely unrelated to α-satellites10 (Fig. 3b). We mapped paired-end CENP-A nucleosome sequences and found strong enrichment at each of the neocentromeres we examined (Fig. 3a–c; Supplementary Table 1), in good agreement with earlier mapping efforts6,8,10. The vast majority of CENP-A nucleosomes at the neocentromere fall in the three CENP-A nucleosome size classes (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3c; three bins: 100–119bp, 120–139bp, 140–160bp), and we found that all three size classes map to the same positions (Fig. 3d–i and Supplementary Figs. 3–5; Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 3. The three size classes of CENP-A nucleosomes localize to the same prominent positions on neocentromeres.

(a–c) Bowtie-mapped paired-end CENP-A native ChIP-Seq reads in three different human neocentromere-containing cell lines (PDNC4, MS4221, IMS13q; ideograms, top) demonstrate the specificity of CENP-A native ChIP. The IMS13q neocentromere was formed on an aberrant chromosome with an inversion duplication. The MS4221 neocentromere contains repetitive DNA denoted by dashed lines with strikethrough. (d–i) Occupancy maps for the three different size classes of CENP-A nucleosomes along the length of the neocentromere for PDNC4 (d), MS4221 (f), and IMS13q (h) and within a subsection (2500 bp window) in (e, g, and i).

The finding that the small (~110 bp), medium (~130 bp), and large (~150 bp) fragments localize to the same genomic positions (as opposed to distinct ones) is consistent with the notion that CENP-A nucleosomes have DNA termini that transiently unwrap and are thus prone to variable terminal nuclease digestion. Indeed, co-localization of all three size classes is evident for both quantitative global analysis of the entire neocentromere regions (Fig. 3d,f,h and Supplementary Figs. 3d, 4a, 5a; Supplementary Table 2) and for local analysis of CENP-A nucleosome sites (Fig. 3e,g,i and Supplementary Figs. 3f–m, 4b–i, 5b–g; Supplementary Table 2). Initial removal of duplicate reads yielded similar results (Supplementary Fig. 3e,n), indicating that the DNA wrapping behavior we observe is entirely attributable to positioning of CENP-A-containing particles. Despite originating at diverse genomic locations on separate chromosomes, and with highly variable sizes and patterns of CENP-A nucleosome enrichment (Fig. 3a–c), the wrapping behavior of individual CENP-A nucleosomes is strikingly similar for all three of the neocentromeres we examined. In total, our analysis of neocentromeres strongly suggests that the DNA wrapping properties of CENP-A-containing particles are largely independent of DNA sequence variation in complex DNA and can be attributed to the physical properties conferred by the presence of CENP-A.

CENP-A nucleosomes on repetitive DNA of normal centromeres

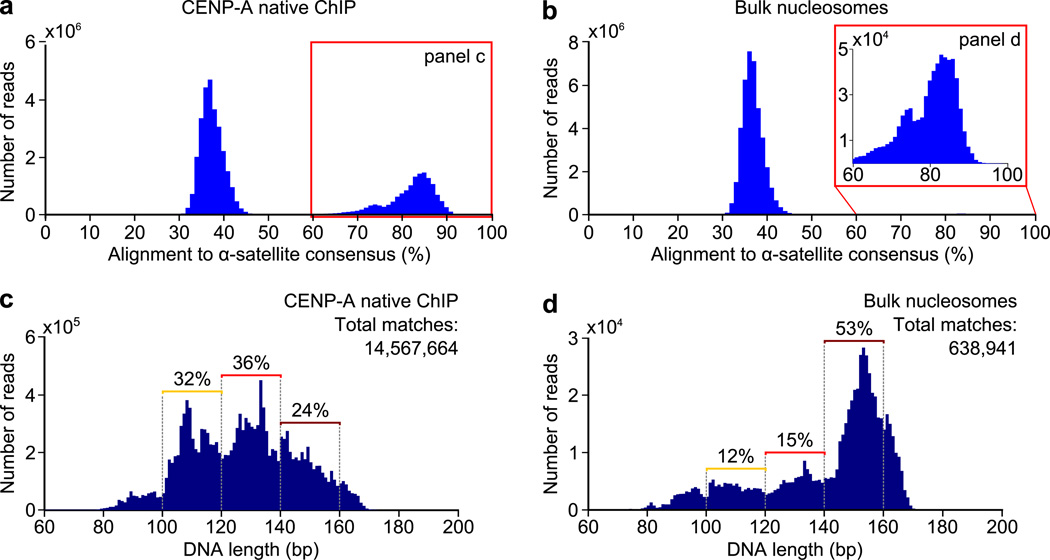

The highly repetitive nature of the DNA sequences found at normal centromere raises the possibility that nucleosome positioning and DNA wrapping is more ordered on α-satellite DNA. Indeed, there are preferred MNase digestion sites of CENP-A-containing chromatin within α-satellite monomers36. Centromeres remain largely unannotated, and standard genomic sequence filters discard these sequences. We developed a scheme that takes advantage of paired-end and long (100 bp) deep sequencing reads (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b) and the fact that α-satellite monomers share >60% sequence identity to one another35. Without both paired-end and long reads, it is impossible to identify the length or sequence of nucleosome protected MNase fragments within such highly repetitive DNA. Our scheme is to align nucleosome sequences to a dimer α-satellite consensus sequence (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b)35,36. In doing so, we include all sequences that map within a single 171 bp monomer or span two monomers. For all three of the cell lines that we examined, we observed a biphasic behavior of CENP-A nucleosome sequence alignments with a subset of sequences having an alignment value of 35–40% and another at ≥60% (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 6c,g). The former subset represents the alignment value of random sequences (i.e. sequences that do not originate from α-satellite DNA). The latter subset (≥60% identity shared with the α-satellite consensus) represents bona fide α-satellite sequences. CENP-A nucleosome ChIP preparations are strongly enriched for α-satellite DNA, representing 35–52% of the sequences for each of the three cell lines used in this study (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 6c,g). ~1.5% of bulk nucleosome sequences are from α-satellite DNA and align with ≥60% identity, and this equates to 4–7×105 bulk nucleosome sequences at centromeres (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6d,h) for us to compare to their counterparts containing CENP-A.

Figure 4. CENP-A nucleosomes on the repetitive α-satellite DNA of normal centromeres have a tripartite distribution of nuclease protected DNA fragments.

(a,b) Alignment of CENP-A (a) or bulk nucleosome (b) fragments to a dimer α-satellite consensus sequence. (c,d) Distribution of DNA lengths of all CENP-A (c) or bulk nucleosome (d) fragments aligning to the α-satellite consensus sequence with ≥ 60% identity.

The tripartite distribution of size classes of MNase digestion of CENP-A nucleosomes includes 17–24% of the large bin (140–160 bp), 36–42% for the middle bin (120–139 bp), and 32–38% for the small bin (100–119 bp), with small variation observed between experiments performed in the three cell lines used in this study (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 6e,i). The tripartite distribution is in stark contrast to bulk nucleosomes on α-satellite DNA, where MNase protection of 140–160 bp, or slightly larger, predominates (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 6f,j), consistent with fully wrapped nucleosomes with or without crossed linker DNA at the entry–exit positions (Fig. 1a). Therefore, even when wrapped with nearly identical sequences—the closely related α-satellite DNA of normal centromeres—CENP-A nucleosomes exhibit distinctly shorter lengths of MNase protection than their conventional counterparts with canonical H3.

Phasing of CENP-A nucleosomes on α-satellite DNA

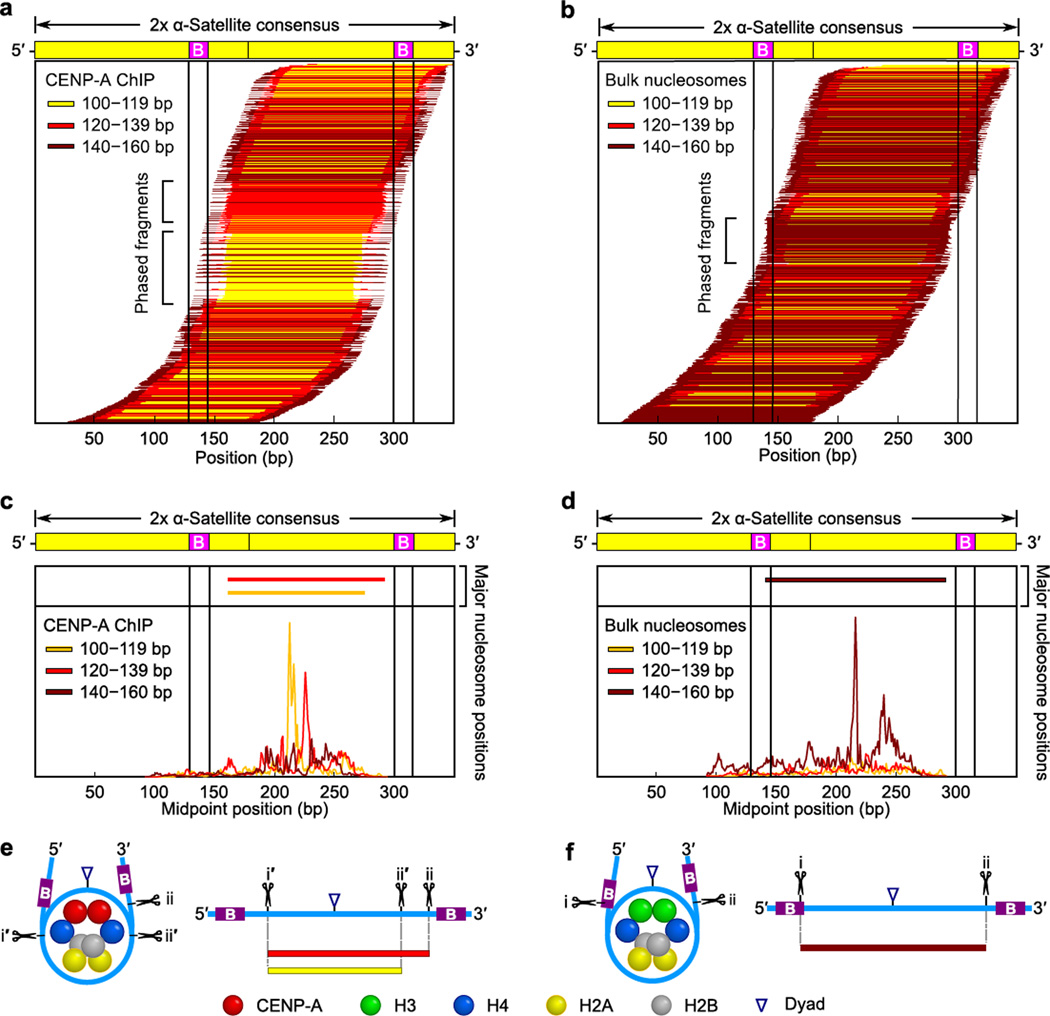

To measure the degree of phasing of CENP-A nucleosomes on α-satellite DNA and investigate the relationship between the three different size classes of DNA fragments protected from MNase digestion, we mapped our sequencing data back to the dimerized α-satellite sequence (Fig. 5). CENP-A nucleosomes are highly phased on α-satellite DNA, with the small (100–119 bp) and medium (120–139 bp) MNase protected fragments showing the highest level of phasing (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 7a,d). The small- and medium-sized MNase protected fragments share a 5’ digestion site ~15–20 bp 3’ of the position of the CENP-B box (a 17 bp binding site for the CENP-B protein37), with the smallest fragments digested ~20 bp shorter than the medium-sized fragments at their 3’ end (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 7a,d). Phasing of bulk nucleosomes on α-satellite DNA is less pronounced, but there is one clearly preferred site with MNase digestion near the 3’ end of the first CENP-B box and ~5–10 bp 5’ of the second CENP-B box (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 7b,e).

Figure 5. Terminally unwrapped CENP-A nucleosomes and their conventional counterparts with wrapped termini are similarly phased at normal centromeres.

(a,b) The position of each individual CENP-A (a) or bulk nucleosome (b) along a dimerized α-satellite consensus sequence is indicated by a horizontal line. Each fragment is color-coded based on length, as indicated. (c,d) The midpoint positions of CENP-A (c) or bulk nucleosome (d) fragments along the dimer α-satellite consensus sequence. Solid vertical lines indicate the location of the 17 bp CENP-B box (B) in (a–d). (e,f) Models of the preferred positioning and MNase cleavage sites on CENP-A (e) and bulk (f) nucleosomes at normal centromeres.

We predicted that CENP-A-containing and H3-containing octameric nucleosomes have similar preferred sites on α-satellite DNA since the basic residues that contact nucleosomal DNA are largely conserved on the surface of the (CENP-A–H4)2 heterotetramer relative to (H3–H4)2 (Fig. 1)14,15. Upon plotting the midpoints of all nucleosome sequences that map to α-satellite DNA, we found that the most prominent position of the small (100–119 bp) MNase fragments from CENP-A nucleosomes is identical to the most prominent bulk nucleosome position (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7c,f; compare yellow trace of the CENP-A ChIP to the maroon trace of the bulk nucleosomes). The midpoint of the middle-sized MNase fragments from CENP-A nucleosomes is shifted 10 bp 3’ of the midpoint of the small-sized CENP-A fragments and canonical nucleosomes (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7c,f; red trace of the CENP-A ChIP). Together, these data argue for a model for nucleosome positioning on α-satellite DNA wherein: 1) canonical nucleosomes prefer a site between CENP-B boxes and maintain strong terminal DNA wrapping with their dyad axis positioned at or very near the midpoint peak we observed (Fig. 5d,f; maroon tracing), 2) the small-sized CENP-A fragments (Fig. 5c,e; yellow) represent MNase digestion of 15–20 bp from each end of a nucleosome with identical dyad axis positioning, and 3) the medium-sized CENP-A fragments (Fig. 5c,e; red) represent asymmetrically digested MNase products that have been cleaved 15–20 bp at their 5’ end but not their 3’ end. Further, CENP-A nucleosomes at their most prominent position at centromeres do not strongly protect fragments >140 bp (Fig. 5). To the contrary, the >140 bp fragments protected by CENP-A nucleosomes are not well phased (Fig. 5a,c). Thus, in the context of their preferred biological context on the chromosome, CENP-A nucleosomes are strongly phased and their propensity to unwrap DNA at their termini is accentuated, especially at the 5’ nucleosome entry–exit site (Fig. 5e; for CENP-A nucleosomes, the i’ site is almost always the site of cleavage, and the i site is very rarely used).

The role of CENP-B boxes in CENP-A nucleosome phasing

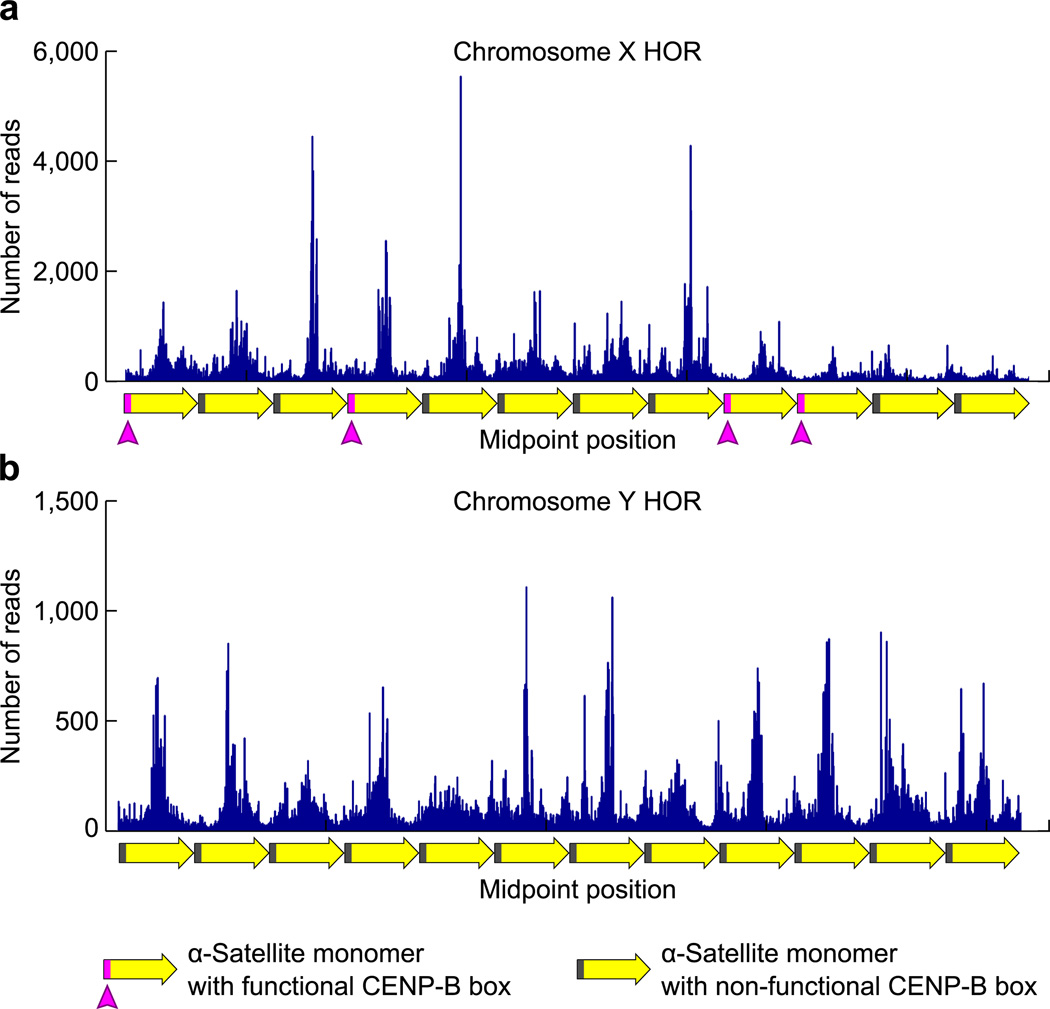

Since our initial analysis (Fig. 5) suggests a strong relationship between the positioning of CENP-B boxes and the CENP-A nucleosome, we next investigated the extent to which CENP-A nucleosome phasing is dependent upon functional CENP-B boxes. The mapping scheme we first employed to examine the phasing of CENP-A nucleosomes on α-satellite DNA revealed that the most prominent CENP-A nucleosome location in the genome yields MNase-digested fragments that exclude the location of the CENP-B box (Fig. 5a). Thus, such a mapping strategy based on consensus sequence does not allow us to directly assess the relationship of these nucleosome positions relative to functional CENP-B boxes that contain the key nucleotide sequence for recognition by the CENP-B protein37. Therefore, we further examined CENP-A nucleosome positions in chromosome-specific higher-order repeat (HOR) α-satellite DNA sequences that have been identified for almost all human chromosomes, although many are poorly annotated in the human genome38. Most of these HORs contain a functional CENP-B box in some fraction of their monomers. Here we chose to examine the well-characterized 2 kb HOR from the X chromosome which contains functional CENP-B boxes in 4 of its 12 monomers (Fig. 6a)38,39. We compared this to the α-satellite HOR found on the Y chromosome, which does not contain any functional CENP-B boxes, and in fact the Y chromosome is the only chromosome that does not show any binding of the CENP-B protein at its centromere40,41. Since we have contiguous end-to-end sequence reads for all of the CENP-A nucleosome derived DNA sequences, we can effectively align them to these HORs. For instance, two of the neocentromere cell lines we use are derived from females, and yield almost no CENP-A nucleosome-derived fragments that align with the chromosome Y HOR (Table 1). One cell line, MS4221, is derived from a male and yields >500,000 CENP-A nucleosome-derived fragments that align with the chromosome Y HOR (Table 1). Thus, our mapping strategy is extremely stringent and provides an attractive means to very faithfully and precisely assign CENP-A nucleosome-derived fragments to their location within annotated HORs.

Figure 6. Phasing of CENP-A nucleosomes at annotated regions of α-satellite DNA from the X and Y chromosomes.

(a,b) CENP-A nucleosome midpoint positions are shown along an annotated region of the 2 kb, 12 monomer HOR of α-satellite from the X chromosome (a) or a 12 monomer portion of the Y chromosome HOR (b).

Table 1.

CENP-A reads at HORs

| Number of Sequences at HORs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line | Gender | Chromosome X | Chromosome Y |

| PDNC4 | Female | 936,641 | 0 |

| MS4221 | Male | 493,734 | 551,277 |

| IMS13q | Female | 1,027,947 | 23 |

Pronounced phasing is apparent on each HOR with the midpoints of CENP-A nucleosome positions peaking at locations between the positions of functional CENP-B boxes (Fig. 6a; magenta boxes in monomer diagrams) or where they would be located on monomers lacking functional CENP-B boxes (Fig. 6a,b; grey boxes in monomer diagrams). Since the Y chromosome α-satellite HOR completely lacks a functional CENP-B box, such phasing on the Y HOR indicates that CENP-B box-independent phasing clearly occurs (Fig. 6b). An additional contribution to CENP-A nucleosome phasing by functional CENP-B boxes is suggested at the chromosome X HOR where the monomer sequences that are more than one full monomer away from a functional CENP-B box appear to contain a broader distributions of midpoints (Fig. 6a; dashed box). At these locations, many CENP-A nucleosome midpoint positions fall within the coordinates of the non-functional CENP-B boxes. Further, the difference between the prominent peaks of CENP-A position and valleys between them appears to be more pronounced on the X than on the Y. Thus, aligning CENP-A nucleosome positions on α-satellite DNA suggests a strong CENP-B-box-independent phasing component encoded within the α-satellite monomer and that additional ‘fine-tuning’ by CENP-B-box-dependent phasing may exist.

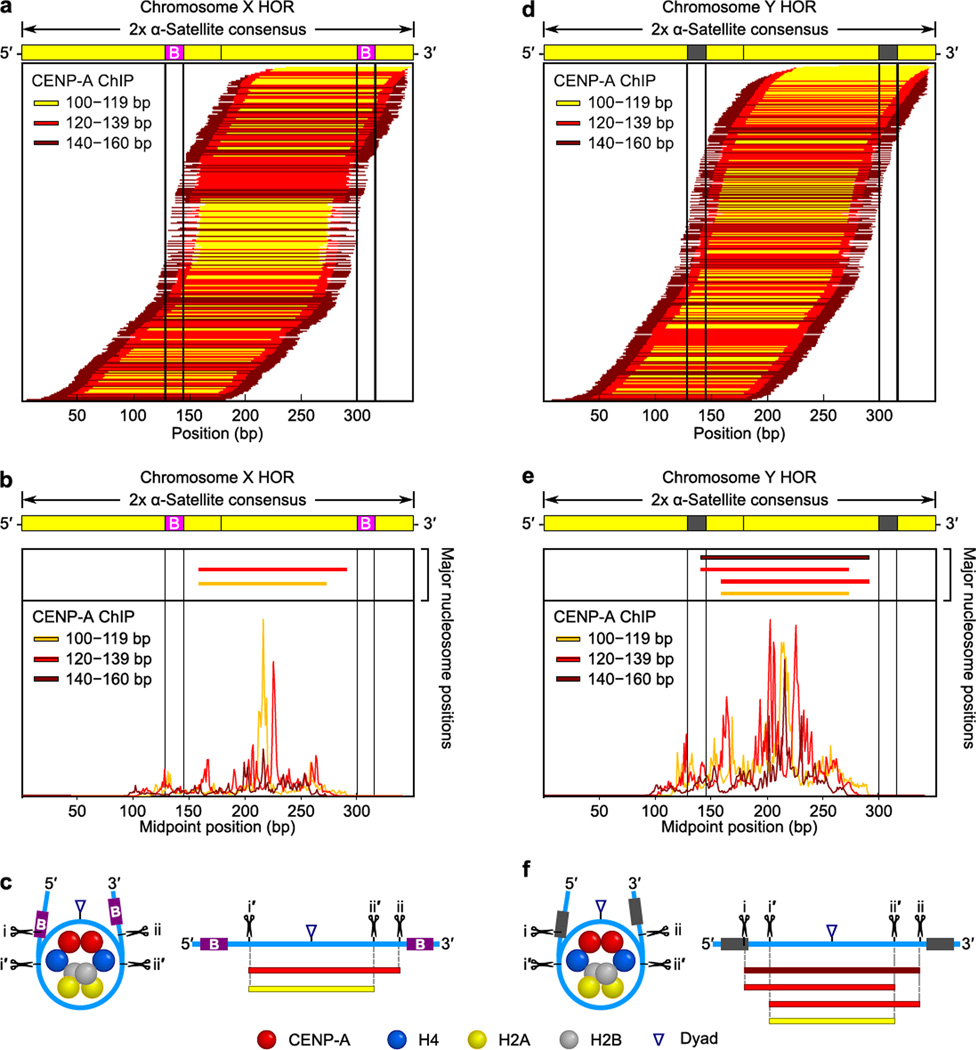

To examine the extent to which CENP-B-box-dependent phasing of CENP-A nucleosomes occurs, we mapped the chromosome X and Y HOR CENP-A nucleosome sequences to the dimer α-satellite consensus (Fig. 7). Strikingly, the phasing on the chromosome Y HOR is specifically diminished relative to the chromosome X HOR (note that the X HOR [Fig. 7a–c] is very similar to the phasing of CENP-A nucleosome sequences from all α-satellite sequences [Fig. 5a,c and Supplementary Fig. 7a,c,d,f]). The CENP-B box-independent phasing on the chromosome Y HOR (Fig. 7d,e) remains strong enough, however, to still clearly observe the most prominent position(s) for each small, medium, and large CENP-A nucleosome-derived fragments (Fig. 7e). These positions indicate that the central dyad of the preferred CENP-A nucleosome position on the chromosome Y HOR (Fig. 7f) is the same as deduced from our analysis on all α-satellite sequences (Fig. 5e). On the chromosome Y HOR, however, the i and ii MNase cleavage sites are used equally (Fig. 7f), as opposed to the sharp asymmetry observed on the X HOR (Fig. 7b,c) or globally on the CENP-A nucleosome-derived fragments on α-satellite DNA from all chomosomes (Fig. 5e).

Figure 7. CENP-A nucleosomes are less phased and gain symmetric MNase digestion on the Y chromosome centromere that lacks functional CENP-B boxes.

(a–c) Maps of chromosome X HOR-aligned CENP-A sequences. (d–f). Maps of chromosome Y HOR-aligned CENP-A sequences. Data and models are shown in the same manner as for the global analysis of CENP-A nucleosome-associated α-satellite sequences (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Regarding the fundamental unit of centromere specifying chromatin, we report nuclease digestion experiments that demonstrate a remarkable similarity in the behavior of octameric CENP-A-containing nucleosomes reconstituted with recombinant components and the form present at functional human centromeres. We conclude that the predominant form of CENP-A particles at functional centromeres is an octamer with loose terminal DNA based on several key findings: 1) the smallest CENP-A containing particle protects ~110 bp from MNase digestion, which is ~30–50 bp longer than what could be accommodated by tetrameric models, 2) three size classes of CENP-A particles all map to the same nucleosome positions on the complex DNA of neocentromeres, and 3) CENP-A nucleosomes at normal centromeres share the same apparent dyad axis positioning as their conventional counterparts containing H3 on the 171 bp α-satellite DNA repeat sequence.

Our findings do not exclude the possibility that a minor population of CENP-A-containing particles with special stoichiometry exists, nor do they exclude the possibility that other forms exist at particular steps during a cell cycle coupled program of CENP-A nucleosome maturation and propagation18. Mutation at the CENP-A–CENP-A interface abrogates CENP-A accumulation at centromeres42,43, suggesting a particle with two copies of CENP-A is required at least transiently in this program. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements of CENP-A-containing particles that were isolated from phases outside of S-phase are shorter than conventional nucleosomes, but are of similar height at S-phase22. These findings were interpreted as evidence for hemisomes as the predominant form through the majority of the cell cycle22. The use of AFM-based height measurements to differentiate between hemisomes and octameric nucleosomes from isolated CENP-A-containing particles may not be as straightforward as it originally seemed, since reconstituted, recombinant CENP-A-containing octameric nucleosomes are substantially shorter than their canonical counterparts containing conventional H344. Further, and to this point, in addition to the neocentromere-harboring cell lines derived from healthy tissue, our studies also include the same tumor-derived cell type as used in the AFM study22, HeLa (Supplementary Fig. 2e,f). Under our culturing conditions ~70% of the HeLa cell population is outside of S-phase (Supplementary Fig. 2f). We observe DNA fragment lengths consistent with an octameric CENP-A nucleosomes in HeLa (Supplementary Fig. 2e) with no evidence of the biphasic behavior predicted by a model where there are long periods of the cell cycle where CENP-A forms radically different particles (e.g. a hemisome and octameric nucleosome switching model22). Therefore, since sub-octameric forms are not highly populated in the genome, we conclude that such minor species would be present at very low levels or only very transiently during the cell cycle.

Our findings also uncovered remarkable coupling of the propensity of the CENP-A nucleosome to unwrap its terminal DNA with its strongly phased position within the 171 bp monomer unit of centromeric α-satellite DNA. We further conclude that CENP-B binding to the CENP-B box generates asymmetric unwrapping of CENP-A nucleosome terminal DNA. Nucleosomes, CENP-A-containing or bulk nucleosomes, are not positioned evenly between the sites of CENP-B boxes within α-satellite monomers. Rather, the site for the CENP-B box is immediately adjacent 5’ of the entry–exit site. Thus, this places the 3’ end of the CENP-B box very near to the nucleosome (Fig. 5e,f). CENP-B binding induces a ~60° bend in the DNA with the strongest kink induced 4 bp from the 3’ end of the CENP-B box45. We think it is very likely that this property of CENP-B contributes strongly to several chromatin features we observe on α-satellite DNA: 1) the general phasing observed for bulk nucleosomes, 2) the enhanced phasing we see for CENP-A nucleosomes, and 3) the asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosome terminal DNA that is exquisitely specific to CENP-A-containing nucleosomes that are bounded by CENP-B boxes. To the latter feature, it appears that CENP-A has evolved in a manner that is poised to have its nucleosomal termini unwrapped. It is enticing to speculate that the physical relationship between CENP-A, CENP-B, and α-satellite DNA is a product of co-evolution. Whether at established centromere locations of highly repetitive DNA or at new centromere locations lacking repeats, however, CENP-A marks centromere location as part of an octameric nucleosome with loose termini.

Methods

Nucleosome Reconstitution Experiments

Tetrasomes, nucleosomes, and nucleosomal arrays were reconstituted from purified components using salt dialysis46. Briefly, human histones H3, H4, H2A, H2B were purified as monomers14 and mixed to form (H3–H4)2 tetramer and (H2A–H2B) dimer complexes14,47 while human (CENP-A–H4)2 was purified from a bi-cistronic vector as a tetramer17. The ‘601’ 1× 200 bp and ‘601’ 12× 200 bp DNA templates48,49 were both purified by anion exchange chromatography. The indicated histone complexes were combined with the DNA in 2 M NaCl and dialyzed in steps: 1) TE (10 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 0.25 mM EDTA) supplemented with 1 M NaCl, followed by 2) TE supplemented with 0.75 M NaCl, and lastly 3) TE supplemented with 2.5 mM NaCl. Tetrasomes, nucleosomes, or nucleosomal arrays were digested with 2 U/µg MNase (Roche) in the presence of 3 mM CaCl2 for 0.5 to 2 min. Each comparison shown between CENP-A-containing and H3-containing particles was performed in parallel under identical reaction conditions for the same length of time. Each reaction was quenched by addition of 10 µl of 0.5 M EGTA and Buffer QG (Qiagen) and placed on ice. The DNA was purified using a DNA purification kit (Qiagen) and subsequently analyzed by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the DNA 1000 kit.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

For native ChIP, 2–5 × 107 cells were collected and resuspended in 2 ml of ice cold buffer I (0.32 M Sucrose, 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 15 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1:1000 protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma]). 2 ml of ice cold buffer I supplemented with 0.1% IGEPAL was added and placed on ice for 10 min. The resulting 4 ml of nuclei was gently layered on top of 8 ml of ice cold buffer III (1.2 M Sucrose, 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 15 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1:1000 protease inhibitor cocktail) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C with no brake. Pelleted nuclei were resuspended in buffer A (0.34 M sucrose, 15 mM Hepes [pH 7.4], 15 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1:1000 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)) to 400 ng/ul. MNase (Affymetrix) digestion reactions were carried out on 100 µg or more chromatin using 0.9–2.8 U/µg chromatin in buffer A supplemented with 3 mM CaCl2 for 10 min at 37°C. The reaction was quenched with 5 mM EGTA on ice and centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 min. The chromatin was resuspended in 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mM PMSF, 1:1000 protease inhibitor cocktail and rotated at 4°C for 2–4 h. The mixture was adjusted to 500 mM NaCl, allowed to rotate for another 45 min and then centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 min yielding nucleosomes in the supernatant. 100 µg or more of chromatin was diluted to 100 ng/µl with buffer B (20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20) and pre-cleared with 60 µl 50% protein G bead (GE Healthcare) slurry for 20 min at 4°C. 1–2 µg of the pre-cleared supernatant (bulk nucleosomes) was saved for further processing. To the remaining supernatant, antibody was added and rotated overnight at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were recovered by addition of 100 µl 50% protein G bead slurry followed by rotation at 4°C for 3 h. The beads were washed three times with buffer B, and once with buffer B without Tween. For the input fraction, an equal volume of input recovery buffer (0.6 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1% SDS) and 1 µl of RNAse A (10 mg/ml) was added followed by incubation for one hour at 37°C. 100µg/ml Proteinase K (Roche) was then added and was incubated for another 3 h at 37°C. For the ChIP fraction, 300 µl of ChIP recovery buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 20 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 500 µg/ml Proteinase K) was added directly to the beads and incubated for 3–4 hrs at 56°C. The resulting Proteinase K-treated samples were subjected to a phenol-chloroform extraction followed by purification using a Qiagen MinElute column. For crosslinked ChIP, 2–5 × 107 cells were processed with the SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling) using the manufacturer’s recommendations. Unamplified bulk nucleosomes or ChIP DNA was analyzed using Agilent 2100 Bionanalyzer High Sensitivity Kit. The Bioanalyzer determines the quantity of DNA based on fluorescence intensity. Antibodies used for ChIP: mouse α-CENP-A monoclonal (15 µg, ab13939 (Abcam)); rabbit α-H3K9me3 polyclonal (10 µg, ab8898 (Abcam)); rabbit α-H3.3 polyclonal (17 µg, 09–838 (Millipore)).

Next Generation Sequencing

Sequencing libraries were generated and barcoded for multiplexing according to Illumina recommendations with minor modifications. Briefly, 2–15 ng Input or ChIP DNA was end-repaired and A-tailed. Illumina Truseq adaptors were ligated, libraries were size-selected to exclude polynucleosomes, and the libraries were PCR-amplied using Phusion polymerase. All steps in library preparation were carried out using NEB enzymes. Resulting libraries were submitted for 100 bp, paired-end Illumina sequencing on a HiSeq 2000 instrument.

ChIP-Seq Data Processing

Paired-end ChIP-Seq reads were aligned to the human genome build hg19 with Bowtie2 version 2.0.0 using paired-end mode. Reads were aligned using a seed length of 50 bp and only the single best alignment per read with up to 2 mismatches was reported in the SAM file. The aligned mate pairs were joined in MATLAB using the ‘localalign’ function (to determine the overlapping region between the reads [requiring ≥95% overlap identity]) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Duplicate read removal was carried out using the ‘rmdup’ command in SAMtools. To create nucleosome occupancy maps at neocentromeres, all joined reads were aligned to the neocentromere and the number of reads that align with 100% identity are plotted for each particular base pair along the neocentromere coordinate (Supplementary Fig. 3b). For analysis of α-satellite DNA, all joined reads were aligned to the dimerized α-satellite consensus sequence and those reads aligning with ≥ 60% identity were chosen for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b).

Annotated α-satellite Analysis

Paired-end ChIP-Seq reads were aligned to the Chromosome X or Chromosome Y HOR with Bowtie2 version 2.0.0 using paired end mode. Reads were aligned using a seed length of 50 bp and only the single best alignment per read with 0 mismatches was reported in the SAM file. The 2.0 kb Chromosome X HOR was previously described elsewhere39. The 5.8 kb Chromosome Y HOR was determined by performing dot plot analysis on the annotated portion of the centromere on chromosome Y in the human genome build hg19.

Statistical Correlation Analysis

Pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients between nucleosome occupancy maps of various size classes (and between randomly generated datasets) at the neocentromeres were determined using MATLAB. p-values were determined using the Student’s T-test by transforming the correlations to a t-statistic having n-2 degrees of freedom.

Molecular Modeling

Molecular models were generated using PDB ID 1KX5 and 1ZBB for the H3-containing particles and 3AN2 for CENP-A-containing particles. Models of tetrasomes and hemisomes with crossed DNA were generated using linker DNA from 1ZBB and minimized using CNS50,51. The model of the CENP-A nucleosome core particle was generated using DNA from 1KX5. The point in space of DNA crossing was determined as the shortest distance along the projection angle of the DNA between entry and exit sites. All molecular structure figures were generated using PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

FISH and qPCR

ChIP DNA FISH probes were generated and used for metaphase FISH as previously described10. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed as previously described8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank O. Jabado (Mt. Sinai, New York, NY, USA) for help with Illumina sequencing, T. Patel (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA [UPenn]) and B. Cole (UPenn) for advice on data analysis, D. Rogers (UPenn) and B. Gregory (UPenn) for advice, E. Bernstein (Mt. Sinai, New York, NY, USA) for mentoring and advising D.H., M. Lampson (UPenn) for comments on the manuscript, K. Luger (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA), D. Cleveland (University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA), A. Straight (Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA), and D. Rhodes (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, United Kingdom) for plasmids, A. Choo (Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Victoria, Australia) for the cell line harboring the PD-NC4 chromosome, and R. Allshire (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK) for discussing unpublished results. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health research grant GM082989 (B.E.B.), a Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (B.E.B.), a Rita Allen Foundation Scholar Award (B.E.B.), a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (K.J.S.), and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Cancer Society (N.S.). T.P. acknowledges support from US National Institutes of Health grant GM08275 (UPenn Structural Biology Training Grant).

Footnotes

Accession Codes

The sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database with accession number GSE44724.

Author Contributions

D.H. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. K.J.S and T.P. designed and performed experiments, developed new analytical tools, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. M.U.S. developed new analytical tools. N.S. analyzed data and modeled nucleosomes. A.A. performed experiments and provided technical advice on ChIP experiments. P.E.W. directed the project, designed experiments, and analyzed data. B.E.B. directed the project, designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cleveland DW, Mao Y, Sullivan KF. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell. 2003;112:407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendiburo MJ, Padeken J, Fülöp S, Schepers A, Heun P. Drosophila CENH3 is sufficient for centromere formation. Science. 2011;334:686–690. doi: 10.1126/science.1206880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnhart MC, et al. HJURP is a CENP-A chromatin assembly factor sufficient to form a functional de novo kinetochore. J. Cell Biol. 2011;194:229–243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guse A, Carroll CW, Moree B, Fuller CJ, Straight AF. In vitro centromere and kinetochore assembly on defined chromatin templates. Nature. 2011;477:354–358. doi: 10.1038/nature10379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warburton PE. Chromosomal dynamics of human neocentromere formation. Chromosome Res. 2004;12:617–626. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000036585.44138.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amor DJ, et al. Human centromere repositioning ‘in progress’. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:6542–6547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308637101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassett EA, et al. Epigenetic centromere specification directs aurora B accumulation but is insufficient to efficiently correct mitotic errors. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:177–185. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso A, et al. Co-localization of CENP-C and CENP-H to discontinuous domains of CENP-A chromatin at human neocentromeres. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R148. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso A, et al. Genomic microarray analysis reveals distinct locations for the CENP-A binding domains in three human chromosome 13q32 neocentromeres. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2711–2721. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasson D, et al. Formation of novel CENP-A domains on tandem repetitive DNA and across chromosome breakpoints on human chromosome 8q21 neocentromeres. Chromosoma. 2011;120:621–632. doi: 10.1007/s00412-011-0337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dechassa ML, et al. Structure and Scm3-mediated assembly of budding yeast centromeric nucleosomes. Nat Commun. 2011;2:313. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingston IJ, Yung JSY, Singleton MR. Biophysical characterization of the centromere-specific nucleosome from budding yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:4021–4026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.189340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panchenko T, et al. Replacement of histone H3 with CENP-A directs global nucleosome array condensation and loosening of nucleosome superhelical termini. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:16588–16593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113621108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekulic N, Bassett EA, Rogers DJ, Black BE. The structure of (CENP-A-H4)2 reveals physical features that mark centromeres. Nature. 2010;467:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature09323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tachiwana H, et al. Crystal structure of the human centromeric nucleosome containing CENP-A. Nature. 2011;476:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conde e Silva N, et al. CENP-A-containing nucleosomes: easier disassembly versus exclusive centromeric localization. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;370:555–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black BE, et al. Structural determinants for generating centromeric chromatin. Nature. 2004;430:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature02766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black BE, Cleveland DW. Epigenetic centromere propagation and the nature of CENP-A nucleosomes. Cell. 2011;144:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JS, Hayashi T, Yanagida M, Russell P. Fission yeast Scm3 mediates stable assembly of Cnp1/CENP-A into centromeric chromatin. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalal Y, Wang H, Lindsay S, Henikoff S. Tetrameric structure of centromeric nucleosomes in interphase Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuyama T, Henikoff S. Centromeric nucleosomes induce positive DNA supercoils. Cell. 2009;138:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bui M, et al. Cell-cycle-dependent structural transitions in the human CENP-A nucleosome in vivo. Cell. 2012;150:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shivaraju M, et al. Cell-Cycle-Coupled Structural Oscillation of Centromeric Nucleosomes in Yeast. Cell. 2012;150:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizuguchi G, Xiao H, Wisniewski J, Smith MM, Wu C. Nonhistone Scm3 and histones CenH3–H4 assemble the core of centromere-specific nucleosomes. Cell. 2007;129:1153–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll CW, Silva MCC, Godek KM, Jansen LET, Straight AF. Centromere assembly requires the direct recognition of CENP-A nucleosomes by CENP-N. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:896–902. doi: 10.1038/ncb1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll CW, Milks KJ, Straight AF. Dual recognition of CENP-A nucleosomes is required for centromere assembly. J. Cell Biol. 2010;189:1143–1155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw BR, Herman TM, Kovacic RT, Beaudreau GS, Van Holde KE. Analysis of subunit organization in chicken erythrocyte chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1976;73:505–509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Axel R. Cleavage of DNA in nuclei and chromatin with staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2921–2925. doi: 10.1021/bi00684a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Decanniere K, Babu AM, Sandman K, Reeve JN, Heinemann U. Crystal structures of recombinant histones HMfA and HMfB from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanothermus fervidus. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;303:35–47. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong F, Van Holde KE. Nucleosome positioning is determined by the (H3–H4)2 tetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:10596–10600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Read CM, Baldwin JP, Crane-Robinson C. Structure of subnucleosomal particles. Tetrameric (H3/H4)2 146 base pair DNA and hexameric (H3/H4)2(H2A/H2B)1 146 base pair DNA complexes. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4435–4450. doi: 10.1021/bi00337a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Pugh BF. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of the primary structure of chromatin. Cell. 2011;144:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willard HF, Waye JS. Hierarchical order in chromosome-specific human alpha satellite DNA. Trends Genet. 1987;3:192–198. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vafa O, Sullivan KF. Chromatin containing CENP-A and alpha-satellite DNA is a major component of the inner kinetochore plate. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:897–900. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masumoto H, Masukata H, Muro Y, Nozaki N, Okazaki T. A human centromere antigen (CENP-B) interacts with a short specific sequence in alphoid DNA, a human centromeric satellite. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:1963–1973. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudd MK, Willard HF. Analysis of the centromeric regions of the human genome assembly. Trends Genet. 2004;20:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waye JS, Willard HF. Chromosome-specific alpha satellite DNA: nucleotide sequence analysis of the 2.0 kilobasepair repeat from the human X chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2731–2743. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.8.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warburton PE. Epigenetic analysis of kinetochore assembly on variant human centromeres. Trends Genet. 2001;17:243–247. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Earnshaw WC, et al. Molecular cloning of cDNA for CENP-B, the major human centromere autoantigen. J. Cell Biol. 1987;104:817–829. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang W, Colmenares SU, Karpen GH. Assembly of Drosophila centromeric nucleosomes requires CID dimerization. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bassett EA, et al. HJURP uses distinct CENP-A surfaces to recognize and to stabilize CENP-A/histone H4 for centromere assembly. Dev. Cell. 2012;22:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miell MD, Fuller CJ, Guse A, Barysz HM, Downes A, Owen-Hughes T, Rappsilber J, Straight AF, Allshire RC. CENP-A confers a reduction in height on octameric nucleosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:763–765. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka Y, et al. Crystal structure of the CENP-B protein-DNA complex: the DNA-binding domains of CENP-B induce kinks in the CENP-B box DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:6612–6618. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 46.Carruthers LM, Tse C, Walker KP, Hansen JC. Assembly of defined nucleosomal and chromatin arrays from pure components. Meth. Enzymol. 1999;304:19–35. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Richmond TJ. Preparation of nucleosome core particle from recombinant histones. Meth. Enzymol. 1999;304:3–19. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huynh VAT, Robinson PJJ, Rhodes D. A Method for the In Vitro Reconstitution of a Defined ‘30nm’ Chromatin Fibre Containing Stoichiometric Amounts of the Linker Histone. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.