Abstract

Genomes of animals as different as sponges and humans show conservation of global architecture. Here we show that multiple genomic features including transposon diversity, developmental gene repertoire, physical gene order, and intron-exon organization are shattered in the tunicate Oikopleura, belonging to the sister group of vertebrates and retaining chordate morphology. Ancestral architecture of animal genomes can be deeply modified and may therefore be largely nonadaptive. This rapidly evolving animal lineage thus offers unique perspectives on the level of genome plasticity. It also illuminates issues as fundamental as the mechanisms of intron gain.

Tunicates, viewed as the closest living relatives of vertebrates, were probably simplified from more complex chordate ancestors (1). Larvacean tunicates represent the second most abundant component of marine zooplankton and filter small particles by their gelatinous house. Oikopleura dioica is the most cosmopolitan larvacean, has a very short life cycle (4 days at 20°C), and can be reared in the laboratory for hundreds of generations (2). Unique among tunicates, it has separate sexes. We sequenced its genome with high-coverage shotgun reads (14X) using males resulting from 11 successive full-sib matings (figs. S1 and S2 and tables S1 to S3) (3). Two distinct haplotypes were retained, despite inbreeding. Their comparison yielded a high estimate of population mutation rate (θ = 4Neμ = 0.0220) that is consistent with a large effective population size (Ne) and/or a high mutation rate per generation (μ)(3). Sequence comparisons among populations from the eastern Pacific and eastern Atlantic and within the latter revealed low dN/dS values (dN, rate of substitutions at nonsilent sites; dS, rate of substitutions at silent sites) consistent with strong purifying selection, as expected for large populations (3). In 17 of 18 phylogenetic trees constructed with 26 metazoan genomes and nine independent data sets, Oikopleura shows the fastest protein evolution, and even higher evolutionary rates are observed for mitochondrial genes that are heavily modified by oligo- dT insertions (figs. S3 to S6 and tables S4 to S6) (3). Key components of DNA repair, especially in the nonhomologous end-joining pathway, were not detected in the genome (fig. S7 and table S7) (3). Coincident rapid evolution of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes may also reflect a highly mutagenic context at the ocean surface.

At 70 megabases with 18,020 predicted genes, the Oikopleura genome is unusually compact. Introns are very small (peak at 47 base pairs, 2.4% > 1 kb), as are intergenic spaces, partly because of numerous operons (fig. S8 and table S8) (3). Genes outside operons are also densely packed (53% of intergenic distances < 1 kb). Even compared with other compact genomes (4), the density of transposable elements (TEs) is low. Most pan-animal TE superfamilies are absent in Oikopleura, and only two species-specific clades of retrotransposons (5)have diversified. A massive purge of ancient TEs can be invoked, but TEs currently present in the genome show multiple signs of activity (figs. S9 to S16) (3). The low copy number of each element and the uneven genome distribution of the main TE clades suggest tight control of their proliferation (Fig. 1A) (3).

Fig. 1.

Genome compaction features. (A) Chromosome regions assembled with physical links and genetic markers. The location of TEs is indicated with horizontal lines (lines on the left sides, DNA transposons; lines on right sides, short lines for long terminal repeat–retrotransposons and long lines for long interspersed elements). (B) Distribution of gene models over 10% abundance classes of intron size and upstream intergenic distance for 8812 nonoperon genes (left) and for 189 developmentally regulated genes, mainly transcription factors (right). (C) Conserved elements revealed in genome alignments of Atlantic and Pacific ocean populations of O. dioica:density of conserved blocks (top), gene annotation (middle), and perfectly conserved elements >100 bp (bottom gray line) (blue, Norway versus northwest America; red, Norway versus Japan). (D) Giant Y genes and their testis expression revealed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization. hpf, hours post fertilization; ctrl, control. The arrowhead indicates the giant gene expression product.

Two exceptions to global compaction are particularly interesting, as they may illustrate where excessive reduction is harmful. First, a small population of Oikopleura genes has relatively large introns and intergenic spaces (Fig. 1B). It is enriched for developmentally regulated transcription factor genes that are long in other genomes because of an abundance of regulatory elements (6). Regulatory-element sequences can be highly conserved, though rarely across phyla, and Oikopleura homologs of vertebrate conserved elements were not detected (3). However, a comparison of genes encoding developmental transcription factors from Atlantic and Pacific O. dioica revealed short segments of higher sequence conservation in non-coding regions than in exons, suggestive of a rich regulatory content (Fig. 1C and fig. S17) (3). Interestingly, in a revolution of massive intron loss (see below), Oikopleura retained large introns more often than small ones, and the ratio of ancestral to newly acquired introns is highest in developmental transcription factor genes (figs. S18 and S19) (3). Second, Mendelian analysis showed that sex in Oikopleura is genetically determined (fig. S20 and table S10) (3), and we could reconstruct large X and Y chromosomes (Fig. 1A). Seven genes on the Y chromosome, all expressed in the testis during spermatogenesis, have giant introns (Fig. 1D). Their size probably grew with the nonrecombining Y chromosome region, flaunting global compaction.

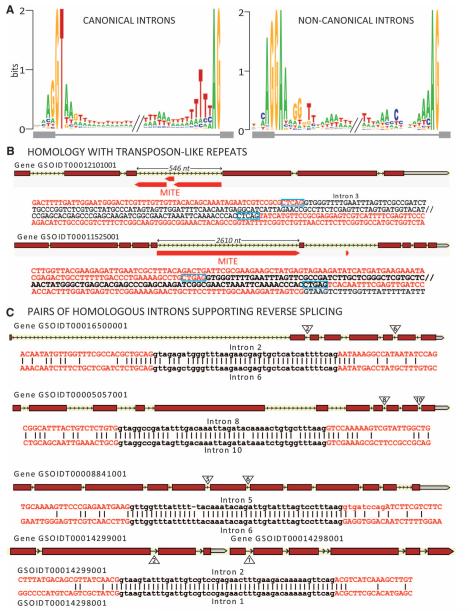

Oikopleura has a rather common number of introns per gene (4.1), but the turnover of its introns has been extraordinarily high: Of 5589 introns mapped by interspecies protein alignments, 76% had positions unique to Oikopleura (newly acquired introns), 17% were at ancestral positions (old introns), and 7% could not be classified (fig. S21) (3). Noncanonical introns, mostly GA-AG and with a very specific acceptor site, are unusually frequent (12%) (Fig. 2A and figs. S22 to S25) (3). They show several peculiarities (tables S11 and S12), including preferential insertion in phase 1, which is compatible with the current codon usage, as would be expected for the most recently gained introns (3, 7). The most distinctive feature of newly acquired introns (figs. S26 and S27 and tables S13 to S15) is that they are more often noncanonical than old introns (8.4 versus 2.6%) (3). Because Oikopleura lacks the minor spliceosome and has only one type of each spliceosomal component, we propose that a single and permissive major spliceosome is used, with U1snRNP (where snRNP is small nuclear ribonucleoprotein) and U2AF able to recognize donor and acceptor sites (3, 8, 9). cDNA sequence information suggests an efficient splicing for the vast majority of introns. A permissive spliceosome could favor intron gains by correctly splicing out newly acquired introns. The pattern of intron loss in Oikopleura is consistent with homologous recombination of reverse transcribed mRNA (table S16) (3, 10). Among hypothetical mechanisms of intron gain, we provide evidence for the insertion of transposon-like elements and, more remarkably for reverse splicing, a reaction in which spliced out introns can be ectopically reinserted into transcripts (11). We identified 32 compelling candidate introns for transposon insertion (Fig. 2B and table S17) (3), those matching repetitive elements containing terminal repeats at almost all nucleotides, with exons excluded. These introns were usually hemizygous in genotyped individuals, but one individual was homozygous and displayed spliced transcripts (figs. S28 to S30 and table S18) (3). We also identified four pairs of nearly identical introns (NIIs) with no or very weak similarity in flanking exons (Fig. 2C) (3), which, to the best of our knowledge, represent the first reported candidates for reverse splicing (12). All animals were homozygous for NIIs and had spliced transcripts (fig. S31 and table S19) (3). Notably, introns of each pair of NIIs were found within the same gene or the same operon, suggesting intron propagation within their pre-mRNA. Many newly acquired introns of Oikopleura might have been propagated like these four NIIs before their sequences diverged, because they tend to be adjacent in their host gene (table S20) (3). Competing mechanisms remain possible: First, introns could be reverse spliced into the genome itself, as can group II introns (13). Some, and possibly many, introns of Oikopleura could originate by repair of double strand breaks (DSBs), as proposed for newly acquired introns in Daphnia (14). However, for the four mentioned intron pairs, a repair after a DSB would not readily explain the systematic colocalization of homologous introns in the same transcription unit. No feature in the sequences of those introns in pairs and their surroundings brings particular support for this mechanism (3).

Fig. 2.

Introns and intron gain scenarios. (A) Main intron logos. (B) Transposon insertion: Duplicated insertion sites (framed in blue) allow miniature inverted repeat transposable element (MITE)–like insertions to be spliced out exactly (red, exons; black, introns). (C) Reverse splicing: four pairs of homologous introns (black) and their immediate exonic environments (red).

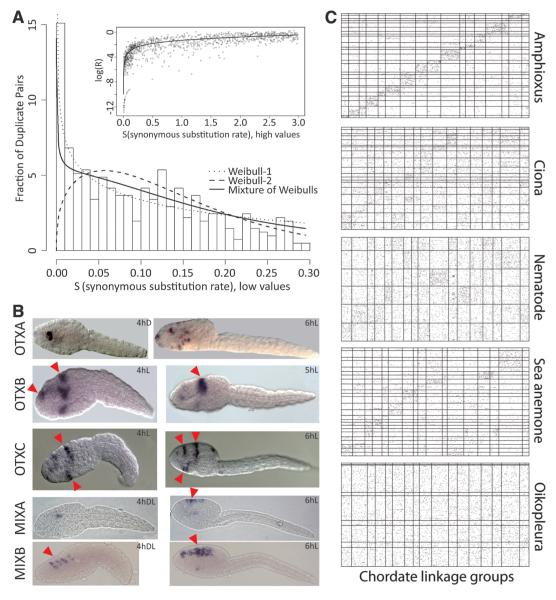

We explored the Oikopleura genome for genes involved in either development or immunity. Many conserved immunity genes failed detection, supporting a minimized immune system consistent with the short Oikopleura life history (Table 1 and table S21) (3). Although frequent gene losses may have affected families of developmental genes, we were most intrigued by an unusually large number of lineage-specific duplicates, thus far reported for homeobox genes only (15): 87 amplifications accounting for 266 current genes (table S22) (3), versus 40 amplifications in Ciona giving 106 current genes (16). A survival analysis of early duplicates in the genome showed that duplicates are initially lost very rapidly with less relaxed selection than in mammalian genomes (17). In contrast, those that survive beyond 0.02 dS units are relatively more likely to be retained (Fig. 3A, figs. S32 to S34, and table S23) (3). To understand how older developmental gene duplicates are used, we focused on homeobox genes. Notably, we detected broad expression signals in the larval trunk epithelium for genes of most amplified groups (16 in 20), but rarely for other groups (1 in 19) (Fig. 3B, fig. S35, and table S24), likely reflecting roles in patterning of the house-building epithelium (18), a crucial novelty of larvaceans. A preferential retention of duplicates for developmental genes has occurred in vertebrates after whole-genome duplications. Their massive retention in Oikopleura is exceptional among invertebrates. In addition to neofunctionalization for complex innovations like house production, another explanation may take into consideration the general reduction of gene size in Oikopleura. This may enhance the likelihood for developmental genes to escape truncation after the local rearrangements that cause duplications (19). Other mechanisms may facilitate duplications or preserve developmental gene duplicates in Oikopleura.

Table 1.

Minimal immune system predicted from the Oikopleura genome. Numbers of genes or domains in families encoding potential immunity factors. D.m., Drosophila melanogaster; S.p., Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; O.d., Oikopleura dioica; C.i., Ciona intestinalis; B.f., Branchiostoma floridae; P.m., Petromyzon marinus; H.s., Homo sapiens. TLR, Toll-like receptor; NLR, NOD-like receptor; SRCR, scavenger receptor cysteine-rich; PGRP, peptidoglycan recognition protein; RIG-I, retinoic acid–inducible gene–I; IgSF-ITIM, immunoglobulin superfamily domain with immunoreceptor tyrosine inhibitory motif; DEATH-TIR, DEATH superfamily members with Toll/interleukin-1–receptor domain; SARM1, SAM- and ARM-containing protein 1; TIRAP, Toll/interleukin-1–receptor domain-containing adapter protein; TICAM2, Toll/interleukin-1–receptor domain-containing adapter molecule; PLA2, phospholipase A2. ND, not determined.

| D.m. | S.p. | O.d. | C.i. | B.f. | P.m. | H.s. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensors | |||||||

| TLR | 9 | 222 | 1 | 3 | 48 | 21 | 10 |

| NLR | 0 | 203 | 0 | 20 | 92 | 140–220 | 20 |

| SRCR | 14 | 218 | 1 | 81 | 270 | 287 | 81 |

| PGRP | 15 | 5 | 4 | 6 | >20 | ND | 6 |

| RIG-I–like helicases | 0 | 12 | 0 | ND | 7 | ND | 3 |

| C-type lectins | 32 | 104 | 31 | 120 | 1215 | ND | 81 |

| IgSF-ITIM | >3 | ND | 5 | >6 | >5 | >3 | >50 |

| Adaptors | |||||||

| MyD88-like (DEATH-TIR) | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ND | 1 |

| SARM1-like, TIRAP-like, TICAM2-like |

1 | 15 | 0 | >2 | 12 | ND | 3 |

| Potential effector | |||||||

| PLA2 | 8 | 65 | 128 | 7 | >7 | ND | 11 |

Fig. 3.

Gene duplications and loss of ancestral syntenies. (A) Early gene duplicates. (Main panel) Histogram of binned recent duplicate pairs; a mixture model (discrete distribution plus truncated Weibull distributions) accommodating heterogeneous birth/death processes is fitted. (Inset) Non-synonymous substitution accumulation declines with ongoing synonymous substitution. (B) Expression of amplified homeobox gene groups in the trunk epithelium of larvae (red arrowheads). hD, hours dorsal view; hL, hours lateral view; hDL, hours dorsolateral view. (C) Loss of ancestral gene order. Positions of orthologous genes in a given metazoan genome (y axis) compared with ancestral chordate linkage groups [(CLGs), x axis]. The width of CLGs corresponds to the number of orthologs in a given species. Amphioxus and sea anemone genome segments represent the largest 25 assembled scaffolds, whereas Ciona, nematode, and Oikopleura segments are chromosomes.

Finally, we compared synteny relationships in Oikopleura and several invertebrates to ancestral chordate linkage groups (3, 20). Amphioxus, Ciona, Caenorhabditis, and sea anemone showed many cases of conserved chromosomal synteny (Fig. 3C, figs. S36 and S37, and table S25), but Oikopleura orthologs showed no such conservation. We also measured local synteny conservation between the same species and human (3). Amphioxus, Ciona, Caenorhabditis, and sea anemone (to a much lower degree) displayed significantly higher conservation of neighborhood than expected by chance. Oikopleura showed a local gene order that is indistinguishable from random for distances smaller than 30 genes and a modest level of conserved synteny at larger distances (fig. S38).

We show that multiple genome-organization features, conserved across metazoans including other tunicates and nonbilaterians, have dramatically changed in the Oikopleura lineage. Despite an unprecedented genome revolution, the Oikopleura lineage preserved essential morphological features, even maintaining the chordate body plan to the adult stage, unlike other tunicates. Evolution in this lineage was rapid and probably took place in a context favoring purifying selection against mildly deleterious features. Our results strengthen the view that global similarities of genome architecture from sponges to humans (20–23) are not essential for the preservation of ancestral morphologies, as is widely believed (24–26).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Sars Centre budget, the Functional Genomics (FUGE) Programme of the Norwegian Research Council, Genoscope, and NSF grants IOS-0719577 and DBI-0743374 supported the research. This is publication ISEM-2010-123 of the Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier. GENBANK/European Molecular Biology Laboratory sequence accession numbers are CABV01000001-CABV01005917, CABW01000001-CABW01006678, FN653015-FN654274, FN654275-FN658470, FP700189-FP710243, FP710258-FP791398, and FP791400-FP884219. The sequence data for Capitella teleta, Daphnia pulex, Helobdella robusta and Lottia gigantea were produced by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (www.jgi.doe.gov/) in collaboration with the community of users. We thank I.Ahel,B.Haubold,and oneanonymous reviewer for generous advice. This article is dedicated to Hans Prydz and Kåre Rommetveit for their pioneer roles in the Sars Centre establishment.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1194167/DC1 Methods SOM Text Figs. S1 to S38 Tables S1 to S26 References

References and Notes

- 1.Delsuc F, Brinkmann H, Chourrout D, Philippe H. Nature. 2006;439:965. doi: 10.1038/nature04336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouquet JM, et al. J. Plankton Res. 2009;31:359. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbn132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Supporting methods and results are available on Science Online.

- 4.Eickbush TH, Furano AV. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:669. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volff JN, Lehrach H, Reinhardt R, Chourrout D. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:2022. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolfe A, et al. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen HD, Yoshihama M, Kenmochi N. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marz M, Kirsten T, Stadler PF. J. Mol. Evol. 2008;67:594. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zorio DAR, Blumenthal T. Nature. 1999;402:835. doi: 10.1038/45597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mourier T, Jeffares DC. Science. 2003;300:1393. doi: 10.1126/science.1080559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy SW, Gilbert W. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:211. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy SW, Irimia M. Trends Genet. 2009;25:67. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cousineau B, et al. Cell. 1998;94:451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Tucker AE, Sung W, Thomas WK, Lynch M. Science. 2009;326:1260. doi: 10.1126/science.1179302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edvardsen RB, et al. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:R12. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satou Y, Satoh N. Dev. Genes Evol. 2003;213:211. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0330-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes T, Liberles DA. J. Mol. Evol. 2007;65:574. doi: 10.1007/s00239-007-9041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson EM, Kallesøe T, Spada F. Dev. Biol. 2001;238:260. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katju V, Lynch M. Genetics. 2003;165:1793. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putnam NH, et al. Nature. 2008;453:1064. doi: 10.1038/nature06967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putnam NH, et al. Science. 2007;317:86. doi: 10.1126/science.1139158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava M, et al. Nature. 2010;466:720. doi: 10.1038/nature09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srivastava M, et al. Nature. 2008;454:955. doi: 10.1038/nature07191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch M, Conery JS. Science. 2003;302:1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1089370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lynch M. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:450. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104(suppl. 1):8597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702207104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.