Abstract

We describe here the identification of non-peptidic vinylsulfones that inhibit parasite cysteine proteases in vitro and inhibit the growth of T. brucei brucei parasites in culture. A high resolution (1.75Å) co-crystal structure of 8a bound to cruzain reveals how the non-peptidic P2/P3 moiety in such analogs bind the S2 and S3 subsites of the protease, effectively recapitulating important binding interactions present in more traditional peptide-based protease inhibitors and natural substrates.

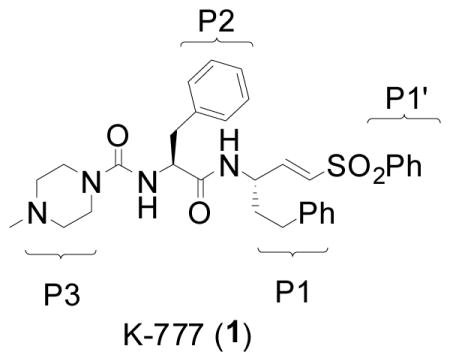

There is an urgent need for new safe and effective drugs to treat the trypanosomal diseases such as Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) and Chagas’ Disease. Existing drugs for these conditions are sub-optimal with regard to efficacy and/or safety, while the lone truly modern drug available for HAT, eflornithine, is difficult to administer in poor rural settings, and is effective only against T. brucei gambiense. Current efforts to address this unmet medical need range from the repurposing of azole antifungals1 in Chagas’ disease to the investigation of a variety of recently identified biochemical targets.2–3 Prominent among the latter are papain-like cysteine proteases such as cruzain in T. cruzi and rhodesain and TbCatB in T. brucei.4 There is now good precedent for targeting cysteine proteases in human disease seeing as inhibitors of related human proteases have progressed into late stage clinical trials (e.g., cathepsin K inhibitor odanacatinib5 for osteoporosis). Among parasite protease inhibitors being studied is the cruzain inhibitor K777 (1), currently in preclinical development as a potential treatment for Chagas’ disease.6

Classical cysteine protease inhibitors comprise a di- or tripeptide linked to an electrophilic warhead that engages the active-site cysteine thiol function reversibly or irreversibly. Such inhibitors readily recapitulate the binding interactions of endogenous substrate (primarily hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions), but as peptides also possess well recognized liabilities as potential drugs. These include susceptibility to enzymatic or chemical hydrolysis of peptide bonds and the metabolism of amino acid side chains, issues that can potentially be addressed through chemical modification of the amino acid backbone and/or side chain. We describe here our initial efforts to identify non-peptidic parasite cysteine protease inhibitors that recapitulate the binding interactions of substrate-like peptidic inhibitors but have a greater likelihood of possessing drug-like properties.

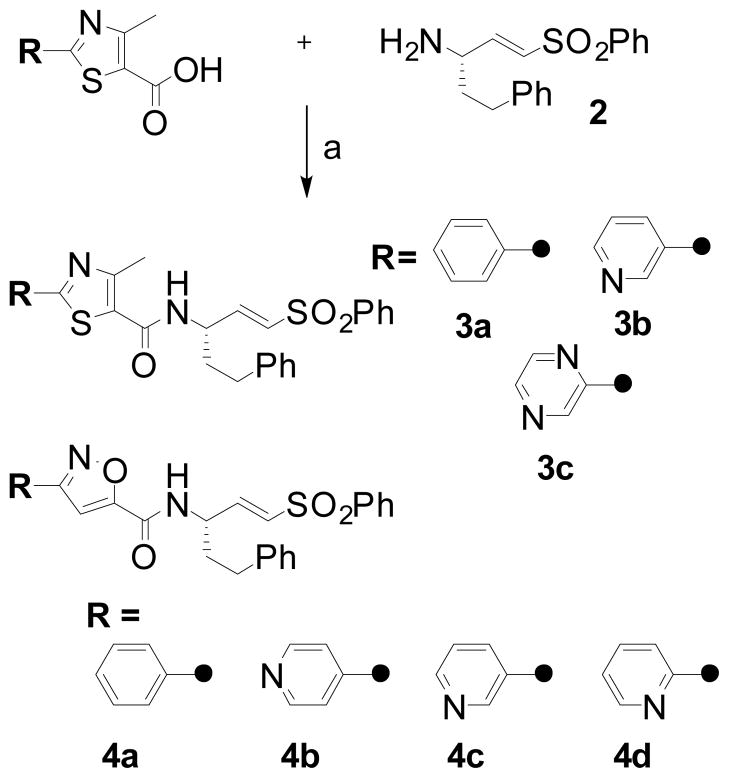

Recently, Ellman and co-workers described a non-peptidic class of cruzain inhibitors discovered via the “substrate activity screening” approach advanced by that lab.7 In the work described here, we similarly aimed to survey non-peptidic fragments as potential P2/P3 moieties, but proceeded by screening the inhibitors directly. While empirical in nature, this effort was guided by the availability of co-crystal structures of substrate-like inhibitors bound to cruzain.8,9 Inspection of these structures suggested to us that an aliphatic or heterocyclic ring might serve as a non-peptidic linkage to a second pendant hydrophobe that would bind in the enzyme’s S2 pocket, playing a role analogous to the phenylalanine side chain in inhibitors like 1. To explore this possibility, carboxylic acids meeting the above design criteria were acquired from commercial sources and coupled to the known vinylsulfone amine 2,10 as illustrated below for a representative series of (hetero)aryl thiazoles (3a–c, Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of non-peptidic vinylsulfones 3a–c from commercially available acids. Conditions: (a) 2-HCl, HATU, DIEA, DMF, rt. The preparation of isoxazoles 4a–d was accomplished from commercially available isoxazole acids (for 4a) or from pyridyl aldehydes as follows for the case of 4d. Conditions (a) 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde, NH2OH, NaOAc, 95% EtOH, reflux, 71% (b) NCS, DMF, 50°C, then methyl propiolate, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 69%; (c) 1.0M LiOH, MeOH-THF; (d) 2-HCl, HATU, DIEA, DMF, rt; 81% over two steps.

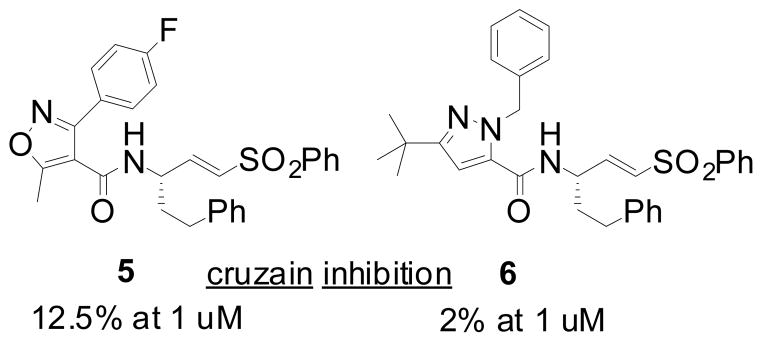

Around thirty non-peptidic vinylsulfones were prepared and IC50 values determined for cruzain, rhodesain, and TbCatB (five minute incubation with inhibitor). True rate constants of rhodesain inactivation were subsequently determined for the most potent analogs (Table 1).11,12 A broad range of potencies were observed for these analogs and some general SAR trends could be discerned. Analogs bearing a single heteroaromatic ring system at P2 were generally devoid of enzyme activity (<5% inhibition of cruzain at 1 uM, data not shown). Similarly ineffective were analogs with a heterocyclic ring linked to a hydrophobe at the ortho position (5 and 6, Figure 1). In contrast, analogs possessing more prolate geometries (e.g. 3a–c) were found to be effective inhibitors of cruzain and quite potent inhibitors of rhodesain. For example, analog 3a inhibited rhodesain with IC50 and Ki values superior to those of 1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Enzymatic and biological activities of vinylsulfone analogs.

| protease inhibition IC50 (uM) | rhodesain inhibition kinetics12 | parasite growth inhibition GI50 (uM) | cytotoxicity IC50 (uM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Cmpd | cruzain | rhodesain | TbCatB | kinact/Ki (M−1s−1) | Kiapp (uM) | kinact (s−1) | T.b.b parasites | Jurkat cells |

| K-777 (1) | 0.004 | 0.007 | 4 | 555,000 | 0.78 | 0.029 | 7 | 3% at 10 uM |

| 3a | 10 | <0.006 | >100 | 84,000 | 0.32 | 0.0018 | >100 | >100 |

| 3b | 2 | 0.03 | >100 | 20,100† | --- | --- | 20 | 98 |

| 3c | 1 | 0.01 | >100 | 25,200 | 4.77 | 0.0079 | 7 | >100 |

| 4a | 2 | 0.01 | 40 | 3,610 | 13.0 | 0.0031 | >100 | >100 |

| 4b | 5 | 0.05 | >100 | 8,590 | 16.2 | 0.0091 | 10 | >100 |

| 4c | 1 | 0.01 | >100 | 348,000† | --- | --- | >100 | >100 |

| 4d | 6 | 0.05 | >100 | 7,720 | 7.4 | 0.0038 | 10 | >100 |

| 7a | 0.05 | 0.1 | 16 | 9,750 | 0.80 | 0.00051 | 12‡ | >100‡ |

| 7b | >100 | 56 | >100 | 2,160 | 4.9 | 0.0007 | nd | nd |

| 8a/b | 0.1 | 0.1 | 45 | 5,740 | 38 | 0.014 | 8 | >100 |

TbCatB: cathepsin B-like protease in T. brucei;

value shown is kass.

tested as the mixture 7a/b.

nd = not determined.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of ineffective vinylsulfone analogs from the initial survey of non-peptidic P2/P3 moieties.

We next synthesized a series of similar analogs (4a–d) in which an isoxazole ring replaces the thiazole ring of 3a–d (Scheme 1). For these analogs, the requisite isoxazole carboxylic acid starting materials were prepared in three steps, employing the [3+2] dipolar cycloaddition of nitrile oxides (generated in situ from the hydroximinoyl chlorides13) with methyl propiolate as a key step (Scheme 1). The isoxazole analogs 4a–d exhibited a similar SAR profile as seen for 3a–c, inhibiting rhodesain more potently than cruzain and conferring no significant inhibition of TbCatB.

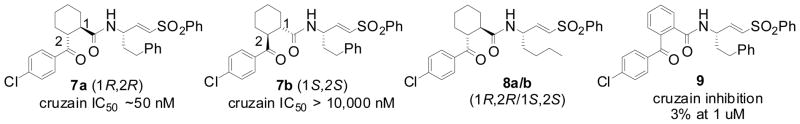

The analogs 7a/b and 8a/b represent a second and structurally distinct series of protease inhibitors that emerged from our survey of non-peptidic P2/P3 fragments (Figure 2). These analogs were prepared as diastereomeric mixtures from the coupling of (±) trans-2-(4-chlorobenzoyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid to vinylsulfone amines. We successfully separated the two diastereomers of 7 and found that one isomer was at least 100-fold more potent than the other, an encouraging result that implied specific binding interactions, presumably involving the S2 and/or S3 subsites of the protease active site.

Figure 2.

Structures of selected non-peptidic vinylsulfones.

To better understand the binding mode of analogs such as 7 and 8, we crystallized cruzain inhibited by 7 or 8 (as diastereomeric mixtures). Cruzain inhibited by 8 provided superior crystals and so we collected diffraction data for these at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), BL7-1 (Table 2). the Traditionally, recombinant cruzain has been expressed in Escherichia coli and purified from refolded inclusion bodies. However, in our experience the final yield of protein was typically in the low milligram range from a multi-liter culture. More recently, we transitioned to an expression system in the yeast Pichia pastoris that produces 10–20 mg of soluble cruzain from four liters of culture. The gene encoding cruzain was engineered to accommodate mutations at two predicted glycosylation sites, Ser49Ala and Ser172Gly (mature domain numbering), preventing the need for deglycosylation of the yeast-expressed protein.

Table 2.

X-ray diffraction data and structure refinement statistics

| Data Collection | |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 44.69, 72.49, 60.93 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 89.8, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.75 (1.84–1.75) |

| Rmerge 1 (%) | 5.7 (13.7) |

| I/σI | 25 (12) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.3 (90.0) |

| Redundancy | 7.4 (7.2) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 11.5 |

| Refinement | |

| Rfree/Rfactor (%) | 17.6/14.3 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 4.46 |

| Rms deviations | |

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.019 |

| bond angles (°) | 1.59 |

| Ramachandran plot 2 | |

| favored (%) | 97.2 |

| allowed (%) | 100 |

| outliers (%) | 0 |

| PDB ID | 3HD3 |

Rmerge = Σ ΣI (h)j − (I (h))/Σ ΣI (h)j, where I (h) is the measured diffraction intensity and the summation includes all observations.

as defined by Molprobity16

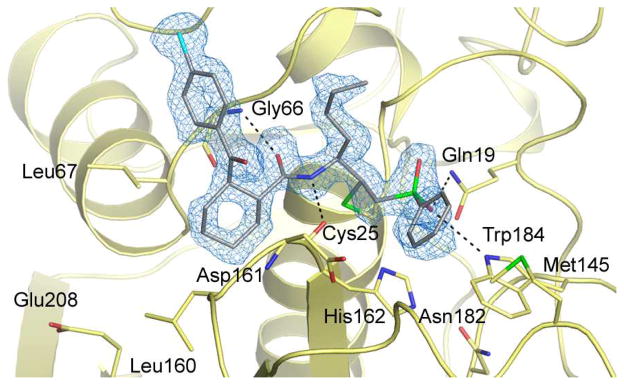

The covalently inhibited complex crystallized with two molecules of the mature domain in the asymmetric unit that superimpose 214 matching αcarbons with root mean square distances (rmsd) of 0.34Å. The high resolution of the diffraction data (1.75Å) allowed us to assign the absolute configuration of the active diastereomer 8a (and by extension 7a) as 1R,2R at the P2 cyclohexane ring (both diastereomers possess the S configuration at P1). Inspection of the cruzain•8a structure reveals that the cyclohexane ring in 8a is located in the S2 subsite of the cruzain active site while the chlorophenyl ring extends over to form hydrophobic contact with the S3 subsite (Figure 3). The importance of cyclohexane ring stereochemistry in 7/8 is further supported by the finding that the benzophenone congener 9 (Figure 2) does not significantly inhibit cruzain (3% inhibition at 1 uM). Apparently a flat aromatic P2 substituent as found in 9 is unable to form favorable contacts with the S2 pocket and/or cannot not properly direct the pendant chlorophenyl moiety towards the S3 subsite.

Figure 3.

The crystal structure of the cruzain•8a complex, solved to a resolution of 1.75 Å. The inhibitor is colored grey and the unbiased mFo-DFc electron density is shown in blue.

Superimposition of our coordinates for cruzain•8a with our earlier cruzain•(1) crystal structure (PDB ID 2OZ2) reveals a number of conserved interactions in the S1, S1′, and S2 subsites. These include the formation of two hydrogen bonds to the inhibitor backbone and another two with the sulfone moiety in the S1′ subsite of the enzyme. Conversely, the presence of a non-peptidic group at P2 in 8a results in the loss of a hydrogen bonding interaction to the inhibitor backbone that is present in the cruzain complex with 1. With respect to S3, the non-peptidic P3 moieties of 1 (N-methyl piperazine) and 8a (4-chlorophenyl) do not make any direct or water-mediated polar contacts with the enzyme (within a 3.5Å cut-off). However, a number of non-polar residues contribute to the binding of 1 and 8a at the S3-S1′ subsites, including Gly65 and Gly 66 at S3, Leu67, Ala138, and Leu160 at S2, Gly23 at S1, and Met145 at S1′. As observed in other structures of cruzain bound by inhibitors with non-polar P2 substituents, the “specificity” residue at the bottom of the S2 subsite (Glu208) points away from the S2 pocket. Only upon binding inhibitors with basic P2 groups (e.g. Arg) is Glu208 seen to point into the S2 subsite.8

Nonpeptidic inhibitors possessing reasonable enzymatic activity were subsequently tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of cultured T. brucei brucei parasites and for general cytotoxicity to mammalian cells (Jurkat). Gratifyingly, many of the non-peptidic vinylsulfones were nearly as effective as 1 against cultured parasites, while conferring no significant toxicity to Jurkat cells. With respect to the anti-parasite effects of 3 and 4, the presence of a nitrogen atom in the pendant aryl ring seems to be important. Hence phenyl substituted analogs 3a and 4a were ineffective against cultured parasites while pyridyl (3b, 4b, 4d) and pyridazyl (3c) analogs exhibited antiparasitic effects at low micromolar concentration. Interestingly, in our earlier study of non-basic analogs of 1, a P3 3-pyridyl analog was found to be more effective against culture T. cruzi parasites than non-pyridyl analogs with superior enzyme activity.14 Since none of these analogs are predicted to be significantly protonated at cytosolic or lysosomal pH, protonation state cannot explain the superior parasite activities of the heteroatom substituted analogs. The effect instead might reflect intrinsic membrane permeability and/or active transport into parasite. Adenosine transporters from T. brucei are implicated in the pharmacology of a number of antitrypanosomals, for example.15

Vinylsulfone analogs 7 and 8 were also examined in the cell-based assays and found to exhibit anti-parasite effects comparable to 1 against T. brucei brucei parasites, without significant cytotoxicity to Jurkat cells (Table 1). These analogs were tested as diastereomeric mixtures, and so one expects that the active diastereomers 7a and 8a should be as much as twice as potent against parasites. While siRNA studies have implicated TbCatB as an important target in T. brucei parasites, the analogs described herein exert a significant anti-parasitic effect in the absence of notable in vitro activity against this enzyme. As irreversible inhibitors however, one cannot rule out inhibition of TbCatB by 3, 4, 7, or 8 in the context of parasite culture where the time scale of exposure is much longer than in a biochemical assay.

In summary, two new classes of non-peptidic vinylsulfone-based cysteine protease inhibitors have been discovered using an empirical but structure-guided approach. Many of the non-peptidic analogs exhibit enzyme and parasite activities comparable to more traditional peptidic inhibitors and none of the non-peptidic species were significantly cytotoxic to Jurkat (mammalian) cells. A co-crystal structure of the non-peptidic vinylsulfone 8a (SMDC-256047) bound to cruzain has been solved to high resolution, demonstrating effective binding to S1′–S3 subsites of cruzain. To our knowledge, this is the first co-crystal structure of a non-peptidic inhibitor bound to cruzain and this structure should greatly facilitate the design of more drug-like parasite cysteine protease inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was generously supported by funding from the Sandler Foundation (to ARR and LSB), and the QB3-Malaysia Program (to KHHA). We thank Dr. P. Vedantham for re-synthesizing a sample of 7a. Part of this research was performed at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Benaim G, Sanders JM, Garcia-Marchan Y, Colina C, Lira R, Caldera AR, Payares G, Sanoja C, Burgos JM, Leon-Rossell A, Concepcion JL, Schijman AG, Levin M, Oldfield E, Urbina JA. J Med Chem. 2006;49(3):892–899. doi: 10.1021/jm050691f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frearson JA, Wyatt PG, Gilbert IH, Fairlamb AH. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23(12):589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renslo AR, McKerrow JH. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(12):701–10. doi: 10.1038/nchembio837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sajid M, McKerrow JH. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;120(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauthier JY, Chauret N, Cromlish W, Desmarais S, Duong le T, Falgueyret JP, Kimmel DB, Lamontagne S, Leger S, LeRiche T, Li CS, Masse F, McKay DJ, Nicoll-Griffith DA, Oballa RM, Palmer JT, Percival MD, Riendeau D, Robichaud J, Rodan GA, Rodan SB, Seto C, Therien M, Truong VL, Venuti MC, Wesolowski G, Young RN, Zamboni R, Black WC. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(3):923–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel JCDP, Hsieh I, McKerrow JH. J Exp Med. 1998;188(4):725–734. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brak K, Doyle PS, McKerrow JH, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(20):6404–6410. doi: 10.1021/ja710254m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillmor SA, Craik CS, Fletterick RJ. Protein Sci. 1997;6(8):1603–1611. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinen LS, Hansell E, Cheng J, Roush WR, McKerrow JH, Fletterick RJ. Structure. 2000;8(8):831–40. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somoza JR, Zhan H, Bowman KK, Yu L, Mortara KD, Palmer JT, Clark JM, McGrath ME. Biochemistry. 2000;39(41):12543–51. doi: 10.1021/bi000951p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian WX, Tsou CL. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1028. doi: 10.1021/bi00534a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodesain (4nM) in 100ul assay buffer was added to inhibitor dilutions in 100ul of 10uM Z-FR-AMC in the same buffer. Progress curves were determined for 360 sec at room temperature for inhibitor concentrations ranging from 100-0.003uM. Inhibitor dilutions that gave simple exponential progress curves over a wide range of kobs were used to determine kinetic parameters. The value of kobs, the rate constant for loss of enzymatic activity, was determined from an equation for pseudo first order dynamics using Prism 4 (GraphPad). When kobs varied linearly with inhibitor concentration, kass was determined by linear regression analysis. If the variation was hyperbolic, kinact and Ki were determined from an equation describing two-step irreversible inhibitor mechanism [kobs = kinact [I]o/([I]o + Ki* (1 + [S]o/Km))] and non-linear regression analysis.

- 13.Liu KC, Shelton BR, Howe RK. J Org Chem. 1980;45(19):3916–3918. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaishankar P, Hansell E, Zhao DM, Doyle PS, McKerrow JH, Renslo AR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(2):624–628. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Koning HP, Jarvis SM. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1162–1170. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, 3rd, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]