Abstract

Aspirin is key to the treatment of acute myocardial infarction, particularly if stent implantation is considered. In patients with a history of hypersensitivity to aspirin, the optimal management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction is unclear. We suggest a strategy for addressing this problem by performing percutaneous coronary intervention with antiplatelet therapy by intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockers and performing rapid oral desensitization in the ensuing hours, once the patient has stabilized.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, allergy, aspirin, desensitisation

Introduction

Aspirin has a class I indication in the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI),1 largely based on its survival benefit in the ISIS-2 trial.2 In addition, patients receiving coronary stents require protracted treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy, using a combination of aspirin and thienopyridines, particularly if percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed in the context of an acute coronary syndrome. Observational studies and randomized trials have established that such therapy is crucial to reducing the risk of acute, subacute, and late stent thrombosis. However, some patients presenting with ACS also report a history of hypersensitivity to aspirin, which creates a conundrum in the treatment decisions. Rapid oral desensitization to aspirin has been proposed but can only be performed on stabilized patients and requires several hours.3 We report here a case of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in a patient with such history, who underwent delayed desensitization to aspirin immediately after emergency rescue PCI.

Observation

A 35-year-old patient with a history of smoking and family history of coronary artery disease was treated with thrombolytic therapy for ST-segment elevation acute inferior myocardial infarction (Figure 1) and admitted less than 2 hours after symptom onset in a hospital without PCI facilities. Because of a history of hypersensitivity to aspirin, the patient received clopidogrel 600 mg and enoxaparin 7000 IU, but no aspirin.

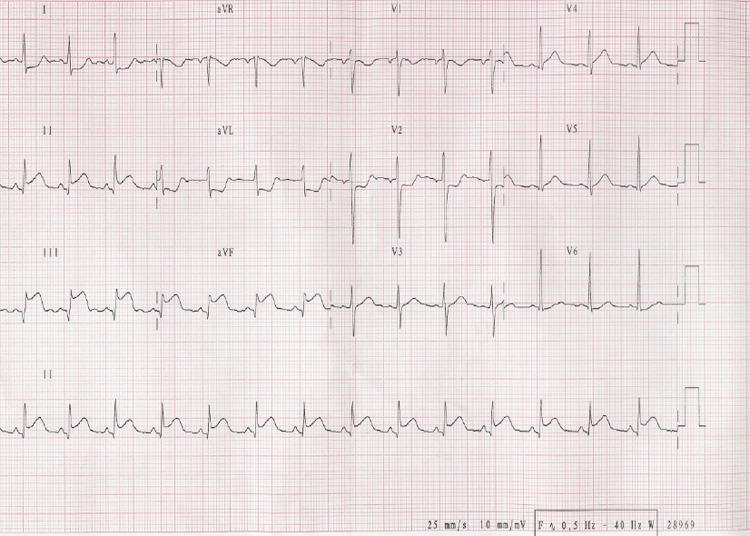

Figure 1.

ECG at admission with persistent ST-segment elevation in the inferior’s leads

Hypersensitivity to aspirin was first documented at the age of 4 with diffuse urticaria and angiooedema immediately following aspirin administration for fever. At the age of 15, the patient presented with giant urticaria following intake of tiaprofenic acid. Allergological testing confirmed hypersensitivity to aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. There was no history of asthma, nasal polyposis, or chronic urticaria.

Following administration of thrombolytic therapy, the patient was transferred to our hospital for emergency coronary angiography due to the lack of clinical and electrocardiographic signs of reperfusion (persistent pain and ST-segment elevation). Coronary angiography, performed via the radial approach, confirmed persistent occlusion (TIMI 1 flow) of the posterior descending artery with a proximal stenosis of the right coronary artery (Figure 2). There was also a stenosis of a lateral branch.

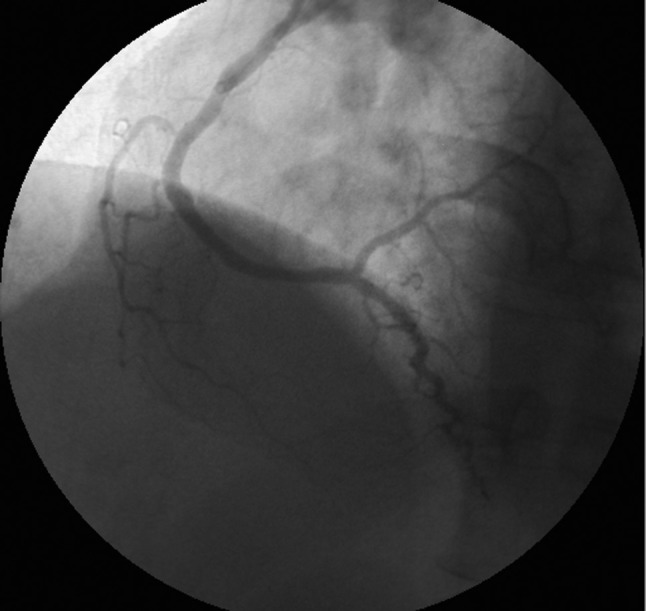

Figure 2.

Posterior descending artery occlusion and right coronary stenosis (segment II)

We were faced with the decision to perform emergency rescue PCI, but with the prospect of having to implant a stent in a patient unable to take aspirin. We elected to provide protracted and complete inhibition of platelet aggregation using a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist, abciximab, to perform rescue PCI, and to plan to subsequently perform rapid desensitization to aspirin in the hours following stent implantation while the patient was still under abciximab therapy.

Rescue PCI was performed uneventfully using two bare-metal stents on the posterior descending artery and the right coronary artery (Tsunami Gold®, 2.5×10 mm and 3.5×18 mm, Terumo, Japan), with a satisfactory final angiographic result (Figure 3). Full-dose abciximab was given, using the standard protocol (bolus 9 ml and infusion 3 ml/h) but we decided to continue the infusion until aspirin desensitization was completed, 16 hours after PCI.

Figure 3.

Post-PCI, with final TIMI flow 3 in the right coronary artery

Desensitization was performed on the next morning, once the patient had stabilized, using a previously described rapid oral desensitization using incremental low doses of aspirin of 5, 10, 20, and 40 mg given at 30 min intervals under strict medical supervision in the coronary care unit, up to a cumulative dose of 75 mg, which is then continued daily using a standard aspirin regimen of 75 q.d. The rest of the hospital course was uneventful, without any hypersensitivity manifestation, bleeding, or other complication. The peak creatine kinase and troponin I values were 2190 UI/l and 49.84 µg/l, respectively. The patient was discharged at day 5 on aspirin 75 mg q.d. and clopidogrel 75 mg q.d. and has had no hypersensitivity manifestation or cardiovascular complication up to a follow up of 4 months.

Discussion

The decision to perform PCI and implant a stent is difficult in patients with a prior history of aspirin hypersensitivity, as the clinical manifestations of the latter may be life threatening. The decision is even more difficult in an emergency setting with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction, when careful assessment of the hypersensitivy and potential desensitization cannot be performed prior to PCI. This case report illustrates a strategy to handle patients presenting with an indication for primary or rescue PCI for STEMI and with a history of aspirin hypersensitivity.

In the present case, the patient received (appropriately) thrombolytic therapy, but aspirin was initially withheld, on the basis of the prior medical history of aspirin hypersensitivity. It is possible that incomplete platelet inhibition due to the lack of aspirin may have contributed to the failure of lytic therapy to recanalize the infarct artery. Rescue PCI was thus clearly indicated4 but performing rescue PCI without potent inhibition of platelet function is also problematic. On the other hand, combination of full -dose lytic therapy and abicixmab incurs an increased risk of major bleeding.5 We elected to take that risk, which we felt was minimized by the young age of our patient and the choice of a radial arterial access route over a femoral one,6 rather than embark on rescue PCI following failed lytic therapy without aspirin or GpIIb/IIIa antagonist.

Aspirin hypersensitivity is present in 0.3–0.9% of the general population,7 but is often overestimated by patients who may tend to ascribe to hypersensitivity a host of unrelated and unspecific symptoms. In the present case, the medical history is compatible with a type-III aspirin hypersensitivity, the mechanism of which involves inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 1 and which is accessible to oral desensitization.8 Several protocols have been described, allowing rapid desensitization in less than 3 hours, using very low initial doses.9 We have adapted this protocol to coronary artery disease3 and have now accrued 54 patients with an acute success rate of 98.1 % and no hypersensitivity complication up to a maximum follow up of 4 years. Once the patient is desensitized, it is important to continue aspirin on a daily low -dose basis and to repeat the desensitization procedure if the treatment is withheld for more than 5 days (as is frequent during noncardiac surgery). In this particular case, PCI coud not be delayed for the several hours required for desensitization, yet intensive antiplatelet therapy was required to avoid acute stent thrombosis. Intravenous glycoprotein Iib/IIIa receptor blocker therapy allowed to safely perform PCI and delay desensitization by a few hours.

Conclusion

In patients with a need for emergency PCI for STEMI and a history of aspirin hypersensitivity, PCI may be performed on GpIIb/IIIa antagonists, with subsequent rapid oral desensitization to aspirin being performed in the following hours once the patient has stabilized. This provides a strategy for handling these difficult cases, while providing optimal platelet inhibition during the procedure.

More experience is needed to clarify the optimal timing of desensitization and whether platelet inhibition is as effective in these patients as it is in patients without hypersensitivity.

Footnotes

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Van de Werf F, Ardissino D, Betriu A, et al. ; The Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 28–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2 ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet 1988; 332: 349–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silberman S, Neukirch-Stoop C, Steg PG. Rapid desensitization procedure for patients with aspirin hypersensitivity undergoing coronary stenting. Am J Cardiol 2005; 95: 509–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel TN, Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of rescue percutaneous coronary intervention after failed fibrinolysis. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97: 1685–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jong P, Cohen EA, Batchelor W, et al. Bleeding risks with abciximab after full-dose thrombolysis in rescue or urgent angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2001; 141: 218–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lo TS, Hall IR, Jaumdally R, et al. Transradial rescue angioplasty for failed thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction: reperfusion with reduced vascular risk. Heart 2006; 92: 1153–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jenneck C, Juergens U, Buechler M, et al. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of aspirin intolerance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2007; 99: 13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gollapudi RR, Teirstein PS, Stevenson DD, et al. Aspirin sensitivity: implications for patients with coronary artery disease. JAMA 2004; 292: 3017–3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong JT, Nagy CS, Krinzman SJ, et al. Rapid oral challende-desensitization for patients with aspirin-related urticaria-angiooedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 105: 997–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]