Abstract

Background:

The cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) has evolved into a complex patient-care environment with escalating acuity and increasing utilization of advanced technologies. These changing demographics of care may require greater clinical expertise among physician providers. Despite these changes, little is known about present-day staffing practices in US CICUs.

Methods and Results:

We conducted a survey of 178 medical directors of ICUs caring for cardiac patients to assess unit structure and physician staffing practices. Data were obtained from 123 CICUs (69% response rate) that were mostly from academic medical centres. A majority of hospitals utilized a dedicated CICU (68%) and approximately half of those hospitals employed a ‘closed’ unit model. In 46% of CICUs, an intensivist consult was available, but not routinely involved in care of critically ill cardiovascular patients, while 11% did not have a board-certified intensivist available for consultation. Most CICU directors (87%) surveyed agreed that a closed ICU structure provided better care than an open ICU and 81% of respondents identified an unmet need for cardiologists with critical care training.

Conclusions:

We report contemporary structural models and staffing practices in a sample of US ICUs caring for critically ill cardiovascular patients. Although most hospitals surveyed had dedicated CICUs, a minority of CICUs employed a ‘closed’ CICU model and few had routine intensivist staffing. Most CICU directors agree that there is a need for cardiologists with intensivist training and expertise. These survey data reveal potential areas for continued improvement in US CICU organizational structure and physician staffing.

Keywords: Cardiac intensive care, cardiovascular medicine, critical care, staffing models

Introduction

The formation of the coronary care unit in the early 1960s transformed the care of patients with acute myocardial infarction by placing emerging diagnostic and therapeutic modalities in a specialized unit staffed by experienced nurses and physicians with focused training in cardiac resuscitation.1 Since then, the coronary care unit has evolved into an increasingly complex, multidisciplinary clinical environment with higher patient acuity and greater utilization of novel technologies.2 Interestingly, the organizational structure and staffing in US cardiac intensive care units (CICUs) appear to have changed very little in the 50 years since their inception.1 In contrast, the structure of general medical and surgical intensive care units have been modified significantly over the past decade.

In response to the radically changing CICU environment, the American Heart Association (AHA) sponsored a writing group to articulate steps toward meeting the changing needs of patients with cardiovascular critical illness.2 This effort revealed a lack of data regarding the operations and staffing of contemporary US CICUs on which to base specific recommendations or benchmark changes. For this reason, members of the AHA writing group2 initiated a survey-based analysis of the current organizational structure and staffing practices of US CICUs and the attitudes of their medical directors toward alterations of these models. This brief report provides the results of this first snapshot of CICU structure in the USA.

Methods

We surveyed medical directors of the ICUs caring for non-surgical cardiac patients in 178 US hospitals to assess the organizational structure and role of clinicians with specialized critical care expertise in these units. Between January 2012 and March 2012, directors from each CICU were contacted by phone and email and asked to complete a 16-question internet-based survey instrument (online appendix). Non-responders were contacted again by phone and email. Data were obtained for 123 CICUs (69% response rate). The survey instrument collected information about the hospital setting, staffing and operational structure, and additionally assessed physician attitudes regarding present and future staffing models. Statistical analyses were performed by the TIMI Data Coordinating Center at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Results

CICU structure

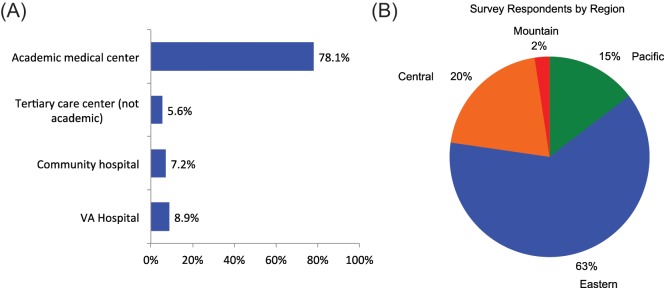

Of the 123 CICUs that responded to the survey, 78% were in academic medical centres, 9% were in Veteran’s Affairs hospitals, and 7% in community hospitals (Figure 1A), representing 35 states covering the eastern, central, mountain, and Pacific regions (Figure 1B). In 68% of hospitals, care for critically ill cardiac patients is provided in a dedicated CICU, with the remainder of respondent hospitals caring for such patients in a general medical ICU (Figure 2A). Of those with dedicated CICUs, 55% report a ‘closed’ unit model in which a CICU-based physician is the attending of record and responsible for all aspects of patient care during the ICU admission. In contrast, 45% of dedicated CICUs employ an ‘open’ unit model with multiple attending physicians caring for their own cardiac patients both within and outside of the ICU. A majority (70%) of respondents reported that they have more than 10 ICU beds available to cardiac patients.

Figure 1.

Clinical setting of CICUs (A); and survey respondents by region (B).

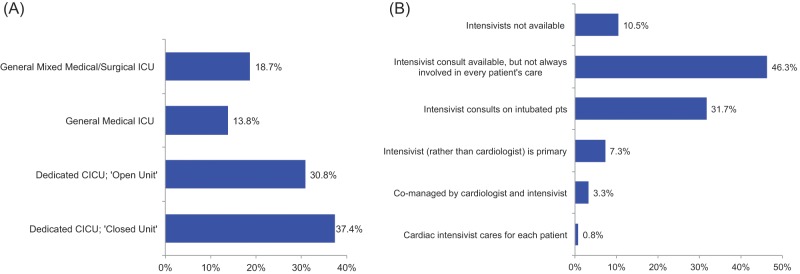

Figure 2.

CICU organizational structure (A) and intensivist availability in CICU care (B).

CICU staffing

Of the ICU directors surveyed, 91% were cardiologists. The majority reported that they spend <50% of their inpatient clinical time in an ICU. Four per cent of the cardiologists were also board-certified in critical care medicine. Nine per cent of respondents were non-cardiologists who were board-certified in critical care medicine.

When asked to describe whether a general intensivist plays a role in the care of critically ill cardiac patients, 46% of respondents reported that an intensivist is available for consultation, but is not involved in every patient’s care (Figure 2B). In 32% of CICUs, a general intensivist consults on every patient requiring mechanical ventilation. A board-certified intensivist was not available to 11% of CICUs surveyed. A majority of respondents (59%) reported that no admitting physicians in their CICU are board-certified in critical care medicine.

Attitudes regarding CICU structure and staffing

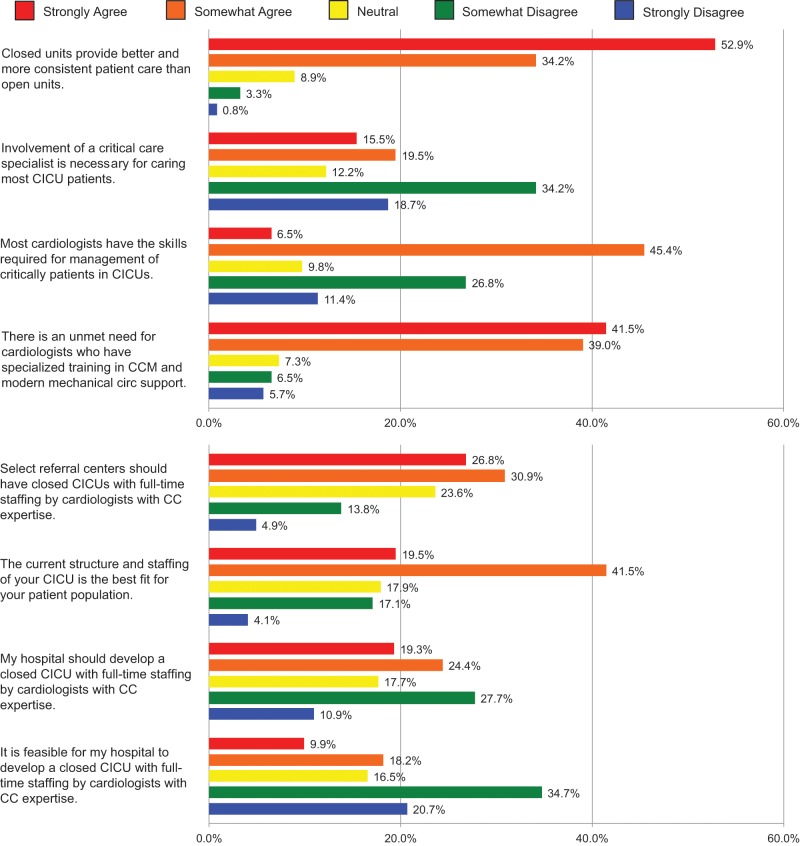

Most of the physicians surveyed (87%) agreed or strongly agreed that closed ICUs, in which a single ICU attending assumes care of all patients, provide higher quality and more consistent care than open units (Figure 3). Greater than 50% of respondents indicated that they believe that most cardiologists have the skills required to manage critically ill cardiac patients. Moreover, a majority of respondents (53%) disagreed with the supposition that involvement of a critical care specialist is necessary for caring for most patients in CICUs. However, a large majority (81%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that there is an unmet need for cardiologists with training in critical care medicine and modern mechanical circulatory support (Figure 3). In addition, 58% of the respondents thought that select referral centres should have closed CICUs with full-time staffing by cardiologists with specialized critical care expertise.

Figure 3.

Attitudes of CICU directors regarding CICU structure and staffing models.

Among the ICU directors surveyed, 61% reported that the current structure of their CICU was the most appropriate for the served patient population. Only 28% agreed or strongly agreed that it was feasible for their hospital to develop a closed ICU with full-time cardiac intensivist staffing. Those who thought that developing a closed CICU with cardiac intensivist staffing was not feasible cited reasons that included inadequate resources, an insufficient number of available cardiac intensivists, and lack of interest in critical care medicine as barriers to implementation. When asked about possibility of changing structure and staffing of CICUs, 44% of respondents thought that their hospital should pursue development of a closed CICU with full-time cardiac intensivist staffing.

Discussion

In this brief report, we describe the contemporary organizational models and staffing practices of 123 US CICUs. In this survey of mostly academically affiliated CICUs, we found that most critically ill cardiovascular patients are cared for in dedicated CICUs by non-intensivist cardiologists. Physician attitudes regarding CICU structure and staffing are varied with respect to the desirability and feasibility of implementing intensivist staffing models. Nevertheless, a large majority of ICU directors believe that there is a need for cardiologists with advanced skills in critical care. These data provide an important first evaluation of the organizational structure and staffing practices in US CICUs from which to identify possible targets for innovation and to benchmark any changes going forward.

Staffing and organization of general ICUs

Practice-based research has provided important insights into the optimal ICU structure and staffing models in general medical and surgical ICUs. Such studies have predominantly demonstrated superior clinical outcomes in ‘closed’ ICU models with ‘high-intensity’ staffing compared with ‘open’ models.3–6 A large meta-analysis of 27 observational studies compared high-intensity staffing (mandatory intensivist consultation or all care directed by intensivist) vs. low-intensity staffing (no intensivist or elective intensivist consultation) in medical and surgical ICUs, and found that high-intensity staffing was associated with lower ICU and in-hospital mortality and length of stay.6 More recently, a retrospective cohort study of more than 65,000 patients from 49 ICUs found that risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was decreased when nighttime intensivist staffing was added to low-intensity daytime staffing, but no advantage was seen in ICUs that employed high-intensity daytime staffing.7 Moreover, an observational study in an academic tertiary ICU comparing continuous in-house intensivist presence vs. daytime-only intensivist staffing demonstrated improved adherence to evidence-based critical care practices, decreased ICU complications, and improved patient satisfaction and staff perception of patient safety and care.8 Lastly, in an academic, mixed medical, surgical, and cardiac intensive care unit, significant cost-savings were shown after transitioning from an ‘open’ non-intensivist staffing model to a ‘high-intensity’ staffing model.9

New considerations in staffing for CICUs

Based on the evidence supporting better clinical outcomes in ICUs with routine intensivist staffing, the 2012 AHA scientific statement on critical care cardiology advocated ‘high intensity’ staffing as the optimal organizational structure for the advanced (level 1) CICU, favouring a closed ICU structure with management by either a cardiac intensivist (preferred), or cardiologists co-managing patients with a collaborating general intensivist.2 CICUs that care for mostly less complicated patients (level 3 CICU) are reasonably staffed predominantly by cardiologists with an intensivist available for consultation on selected complex patients. The AHA scientific statement articulated the importance of providing access to clinicians with specialized clinical expertise in critical care, acquired either by formal training or focused experience and provided by cardiac or general intensivists, for all hospitals that care for critically ill patients with cardiovascular disease.

Current organization and staffing in CICUs

The findings from our survey demonstrate a considerable diversity in the current organization of CICUs in the USA. In a third of hospitals surveyed, care for critically ill cardiovascular patients is provided in a general ICU. Among hospitals with dedicated CICUs, including many academic and tertiary centres where an advanced (level 1 CICU) would be common, there is a near even split of those that employ closed vs. open staffing models. In only 16% of CICUs was the attending of record a cardiologist with a critical care focus, and in less than half of CICUs was an intensivist routinely involved in care. Although prior assessments of ICU organization have been few and have been limited to studies in general medical and surgical ICUs, this finding is consistent with data from 2006 in which an estimated 25% of US general ICUs had an intensivist who managed most (>80%) of the patients, and 50% had no intensivist at all.10

If the roadmap provided by the AHA scientific statement were to be adopted, our survey reveals the need for substantial additional evolution in staffing and organizational models. In addition to the low availability of intensivists (cardiac or general) in US CICUs, only 45% of the CICU directors responding devoted the majority of their clinical experience to the CICU or were board certified in critical care medicine. Some potential barriers to changes in the structure of CICUs are revealed in the reported physician attitudes toward specific CICU staffing models. We found widespread agreement that ‘closed’ ICUs provide superior clinical patient care compared to ‘open’ units, and that there is an unmet need for cardiologists trained in critical care, particularly for staffing selected referral centres. However, most respondents agreed that their current CICU structure was appropriate for their patient population and felt that it would not be feasible for their hospital to develop a ‘closed’ CICU with full-time staffing by cardiologists with critical care expertise. In addition, attitudes varied significantly regarding a necessity for a clinician with intensivist experience to be involved in caring for all or most patients in the CICU. The apparent discordance between CICU directors’ recognition of the need for evolution in critical care cardiology and their self-assessment of their own CICU environment highlights the potential value and importance of quantifying processes, structure, and quality in cardiac critical care.

Limitations

Our study has limitations that should be considered. The survey instrument was not validated. Moreover, results may be affected by response bias and by the small sample of CICUs surveyed. Specifically, CICU respondents were largely from academic medical centres, therefore generalizability to community CICUs may be impacted.

Future directions

These findings regarding the diversity of practice in US CICUs highlight both the significant room for evolution of CICUs and the potential value of the AHA writing group’s proposal to categorize CICUs by level of resources and capabilities that are matched to the populations for whom they routinely provide care. Future surveys that probe the patient make-up as well as the resources of individual CICUs (level 1, 2, or 3) may provide greater insight into the potential needs for maturation of organization and staffing. Moreover, despite efforts to do so, recruitment of community-based CICUs in this survey was unsuccessful and should be a focus of future efforts to capture the full spectrum of cardiovascular critical care. It is plausible that our survey may have underestimated the diversity in practice among CICUs. Nevertheless, this survey takes an important step forward in defining the landscape of the modern CICU and opportunities for additional investigation and evidence-based improvement in care of critically ill cardiovascular patients. In addition to more granular characterization of CICU practice, further research is warranted to assess the effect of organizational models on clinical outcomes in CICUs.

Conclusion

This report provides an initial snapshot of contemporary structural models and staffing practices in a sample of US ICUs caring for critically ill cardiovascular patients. Although most hospitals surveyed had dedicated CICUs, a minority of CICUs have a closed organizational model and few have routine intensivist staffing. These patterns reveal room for growth to meet the evidence-based paradigms that have emerged from general medical and surgical ICUs.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Fye WB. Resuscitating a Circulation abstract to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the coronary care unit concept. Circulation 2011; 124: 1886–1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrow DA, Fang JC, Fintel DJ, et al. Evolution of critical care cardiology: transformation of the cardiovascular intensive care unit and the emerging need for new medical staffing and training models: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 126: 1408–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Sluis FJ, Slagt C, Liebman B, et al. The impact of open versus closed format ICU admission practices on the outcome of high risk surgical patients: a cohort analysis. BMC Surg 2011; 11: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carson SS, Stocking C, Podsadecki T, et al. Effects of organizational change in the medical intensive care unit of a teaching hospital. JAMA 1996; 276: 322–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Multz AS, Chalfin DB, Samson IM, et al. A ‘closed’ medical intensive care unit (MICU) improves resource utilization when compared with an ‘open’ MICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1468–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, et al. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. JAMA 2002; 288: 2151–2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Barnato AE, et al. Nighttime intensivist staffing and mortality among critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2093–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gajic O, Afessa B, Hanson AC, et al. Effect of 24-hour mandatory versus on-demand critical care specialist presence on quality of care and family and provider satisfaction in the intensive care unit of a teaching hospital. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: 36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parikh A, Huang SA, Murthy P, et al. Quality improvement and cost savings after implementation of the Leapfrog intensive care unit physician staffing standard at a community teaching hospital. Crit Care Med 2012; 40: 2754–2759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 1016–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]