Abstract

The balance between endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production determines endothelial-mediated vascular homeostasis. Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) has been linked to imbalance of the eNOS/ROS system, which leads to endothelial dysfunction. We previously found that selective inhibition of delta PKC (δPKC) or selective activation of epsilon PKC (εPKC) reduces oxidative damage in the heart following myocardial infarction. In this study we determined the effect of these PKC isozymes in the survival of coronary endothelial cells (CVEC). We demonstrate here that serum deprivation of CVEC increased eNOS-mediated ROS levels, activated caspase-3, reduced Akt phosphorylation and cell number. Treatment with either the δPKC inhibitor, δV1-1, or the εPKC activator, ψεRACK, inhibited these effects, restoring cell survival through inhibition of eNOS activity. The decrease in eNOS activity coincided with specific de-phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1179, and eNOS phosphorylation at Thr497 and Ser116. Furthermore, δV1-1 or ψεRACK induced physical association of eNOS with caveolin-1, an additional marker of eNOS inhibition, and restored Akt activation by inhibiting its nitration. Together our data demonstrate that 1) in endothelial dysfunction, ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) formation result from uncontrolled eNOS activity mediated by activation of δPKC or inhibition of εPKC 2) inhibition of δPKC or activation of εePKC correct the perturbed phosphorylation state of eNOS, thus increasing cell survival. Since endothelial health ensures better tissue perfusion and oxygenation, treatment with a δPKC inhibitor and/or an εPKC activator in diseases of endothelial dysfunction should be considered.

1. Introduction

Maintenance of endothelial health and function should reduce the risk of diseases associated with vascular dysfunction including cardiovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, atherosclerosis, chronic heart failure, diabetes and stroke. These pathological conditions are all associated with enhanced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced amounts of nitric oxide (NO) [1]. Decreased levels of NO are related to the impairment of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity. Under these conditions, the enzyme is uncoupled and produces O2−[2], which quenches NO leading to the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a potent oxidant affecting protein functions through nitration [3].

The activity of eNOS involves multiple post-translational regulation, numerous protein-protein interactions and tightly regulated multi-site phosphorylation [4]. Inactive eNOS is sequestered in the caveolae through a complex that involves caveolin-1 (Cav-1). Following activation, Cav-1-mediated inhibition of eNOS is reversed by the recruitment of several proteins including heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and is associated with specific phosphorylation of eNOS [4].

There are six different phosphorylation sites on eNOS, each of which has specific effects on the enzyme’s activity. The phosphorylation sites on eNOS are Tyr81, Ser114, Thr495, Ser633, Ser615 and Ser1177 in humans and these are equivalent to Tyr83, Ser116, Thr497, Ser635, Ser617 and Ser1179 in bovine eNOS [5]. Phosphorylation of Ser1179, induced by kinases such as Akt, protein kinase A (PKA) or 5’-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), leads to eNOS activation [6]. On the other hand, Thr497 phosphorylation, promoted by protein kinase C (PKC), is a negative regulatory site and is associated with eNOS inhibition [4, 5].

Oxidative stress leads to alteration in the activation state of PKCs in the vasculature [7]. Specifically, activation of δPKC, one of ten PKC isozymes, increases oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation [8]. Conversely, εPKC activation exerts protective effects, reducing stress and the apoptotic and necrotic cell death processes [9]. Activation of PKCs leads to their translocation from cytosolic soluble fraction to the cell particulate fraction and their binding to selective anchoring proteins, termed RACK (Receptors for Activated C Kinase) [10]. Studies of these protein-protein interactions lead to the rationale development of isozyme-selective translocation peptide inhibitors and activators [11]. Among these peptides, δV1-1, a δPKC-selective inhibitor, and ψεRACK, an εPKC-selective activator, have been found to have a favourable profile of cardio-protection from ischemia/reperfusion damage in preclinical and clinical conditions [12, 13].

Recently, δV1-1 was also found to restore brain blood flow in models of either global or regional ischemia, implying an amelioration of endothelial dysfunction [14]. However, the molecular effect of these selective PKC regulators on endothelial cell functions, directly, has not been determined. Here we postulate that the peptides might affect the survival program of endothelial cells by controlling eNOS activity. We used coronary venular endothelial cells of bovine origin (CVEC) cultured in low serum as a model to produce endothelial dysfunction. We evaluated the action of δPKC inhibition and εPKC activation on Akt and eNOS activity focusing on eNOS phosphorylation status and its interaction with Cav-1 and Hsp90.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines

Coronary post-capillary venular endothelial cells (CVEC) were obtained from bovine heart and cultured as described [15, 16].

2.2. Plasmids and siRNA construct

Asp or Ala mutants of eNOS phosphorylation sites were a kind gift of Prof. Fleming (University of Frankfurt, Germany). Plasmids were named S114A (Ala de-phospho-mimetic eNOS Ser114 phosphorylation), S114D (Asp phospho-mimetic eNOS Ser114 phosphorylation), T495A (Ala de-phospho-mimetic eNOS T495 phosphorylation), and T495D (Asp phospho-mimetic eNOS Thr495 phosphorylation).

The siRNA sequence targeting bovine eNOS(5’-GGAAAGGGAGCGCGACCAA-3’) corresponding to region 1502–1520, was synthetized by Dharmacon (Lafayette, USA). Control siRNA is a random siRNA provided by Qiagen (Valencia, USA) and vector alone used as control (Vector) is pcDNA-3 (Qiagen, Valencia, USA). For annealing of siRNAs, 20 µM of single strands were incubated in annealing buffer (100 mM potassium acetate, 30 mM HEPES-KOH at pH 7.4, and 2 mM magnesium acetate) for 1min at 90°C followed by 1 h at 37°C.

2.3. Cell co-transfection

1.5 × 105 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. 24 h after adhesion, co-transfection (Asp or Ala mutants of human eNOS-Ser114 or -Thr495 phosphorylation sites and siRNA constructs for bovine eNOS) was carried out using Hiperfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, USA). Briefly, 500 ng of plasmid DNA and 1 µg of siRNA were incubated in Hiperfect transfection reagent and medium with antibiotics and without serum, for 10 min at room temperature. During the 10 min incubation, cell medium was removed and cells were washed with PBS. Fresh medium with 1% BCS was replaced with transfection complex and cells were cultured for 24 h, then new fresh media was replaced and cells were deprived of serum for 24 h prior to the start of experiments.

2.4. Cell survival

1.5 × 103 cells were seeded in each well of 96 multi-well plates. After adherence, cells were serum deprived (0.1% bovine calf serum; BCS) for 24 h, treated with the test substances for 24 h, fixed in 100% methanol and stained with Diff-Quick (Mertz-Dade, Italy). Cells were counted at 200 × magnification and data are reported as cells counted/well.

2.5. cGMP assay

Measurement of cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels in cell extracts from confluent CVEC were carried out using an enzyme-immunoassay kit (Cayman, Italy). Cells were pretreated with 1 mM 3-isobutyl-5-methyl-xanthine (IBMX) for 30 min then stimulated with 200 µM L-NG-Nitroarginine methyl ester (hydrochloride) (L-NAME) for 30 min and then stimulated with 1 µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK for 15 min or 6 h as indicated. cGMP levels were assayed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and protein levels were measured by the Bradford procedure.

2.6. Detection of ROS

Intracellular superoxide anion (O2−) were assessed by the dyhydroethidine (DHE) fluorescence/HPLC assay with minor modifications [17]. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were seeded and after 24 h of serum starvation were pretreated with DHE (1 µM, 30 min) and stimulated with test substances for 15 min or 6 h. Cells were scraped with ice-cold PBS and centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 × g, 4°C. 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS together with insulin syringe were used to lyse the cells which were then isobutanol-extracted. HPLC was used to identify the fluorescent product of DHE and O2−, 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+), with a C-18 column (mobile phase: H2O/CH3CN). Fluorescence detection at 480 nm (excitation) and 580 nm (emission) was used. Results are reported as peak area/ mg protein.

2.7. Western blotting

1 × 106 cells were plated in 100 mm diameter dishes, serum deprived (0.1% BCS) for 24 h and then exposed to the different experimental protocols. To assess the δ/ εPKC translocation, cells were treated with δV1-1 or ψεRACK peptides and then homogenized on ice in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell lysates were then separated by centrifugation (100.000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). The supernatant containing the cytosolic fraction and the activated PKC in the pellet were solubilized in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 followed by homogenization with a 25-gauge needle. An equal amount of proteins were loaded on SDS/8% PAGE and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blotting was performed as described [18]. δPKC or εPKC translocation was calculated as described [13].

To assess cleaved caspase-3, phospho-eNOS at Ser116, Thr497, Ser1179 or Ser635, δ/εPKC expression and phospho-Akt, 1 × 106 CVEC plated in 100 mm diameter dishes, were serum deprived for 24 h, and then exposed to the δV1-1 or ψεRACK peptides for 15 min or 6 h. Western blotting was performed as described [18].

2.8. Immunoprecipitation

To study the co-localization of eNOS, δPKC or εPKC with Cav-1 or Hsp90 and the nitration of Akt in response to δV1-1 or ψεRACK, 1 × 106 CVEC were plated in 100 mm diameter dishes, serum deprived (0.1% BCS) for 24 h, then exposed to stimuli and lysed. Anti-Cav-1, anti-Hsp90, anti-eNOS or anti-Akt antibody (4 µg/300 µg total protein) was then added to the pre-cleared lysates for 18 h at 4°C, followed by 2 h of incubation with G protein (100 µL, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Immunoprecipitates were separated in SDS/8% PAGE gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes as described [18].

2.9. Microcarrier cell culture

Cytodex 3 gelatin-coated microcarriers (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) were added to 3 × 105 cells/ml for 6 h and then embedded in a fibrin gel and exposed for 72 h to 1 µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK in the presence or absence of 10 µM LY294002. Micrographs were taken at 100 × magnification. The area occupied by capillary-like formations was quantified as previously reported [19].

2.10. Reagents

δV1-1, amino acids 8–17 [SFNSYELGSL], corresponds to the RACK-binding site in the δPKC C2/V1 domain [12]. ψεRACK, amino acids 85–92 [HDAPIGYD], corresponds to the RACK-binding site in the εPKC C2/V1 domain [12]. Both peptides are conjugated via a cysteine S-S (Cys S-S) bond to the membrane-permeable carrier peptide (TAT) derived from the TAT human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protein [20]. Bovine calf serum was from Hyclone (Celbio, Milan, Italy), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), trypsin, gelatin and analytical grade chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). L-NAME and LY294002 were from Calbiochem (Inalco, Milan, Italy); SIN-1 was from Cayman (Ann Arbor, USA). The polyclonal anti-δPKC and anti-εPKC antibody and the monoclonal anti-Cav-1 were from Santa-Cruz (Santa Cruz CA, USA); the polyclonal anti phospho-eNOS Ser116, anti-phospho-eNOS Ser1179 anti-eNOS Thr 497 were from Upstate (Millipore, Billerica, USA); the monoclonal antibody anti-eNOS and anti-Hsp90 were from BD Transduction (Franklin Lakes, USA); the monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine was from Calbiochem (Inalco, Milan, Italy); anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-phospho-Akt and anti-Akt were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, USA); anti-actin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA).

2.11. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA. A value of p<0.05 was considered to denote statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Serum starvation of cultured endothelial cells as a model of ROS-mediated microvascular dysfunction: effect on endothelial cell survival and apoptosis

Endothelial dysfunction represents the first indicator of vascular damage and it has been shown to be, at least in part, dependent on the production of ROS. To evaluate the role of δ and εPKC isozymes on the endothelium, we treated cultured cells with δV1-1, a δPKC-selective inhibitor [12], or ψεRACK, an εPKC-selective activator [12]. Previous in vivo studies demonstrated that these peptides reduce vascular injuries [7]. Here we set up a model of endothelial dysfunction using chronic nutrient deprivation in culture. To validate this model, we determined ROS production, and Akt and caspase-3 activity using bovine coronary microvascular endothelial cells (CVEC) cultured in low serum (0.1% BCS) for 24 h, and then further exposed to either 0.1% or 10% BCS for 15 min or 6 h.

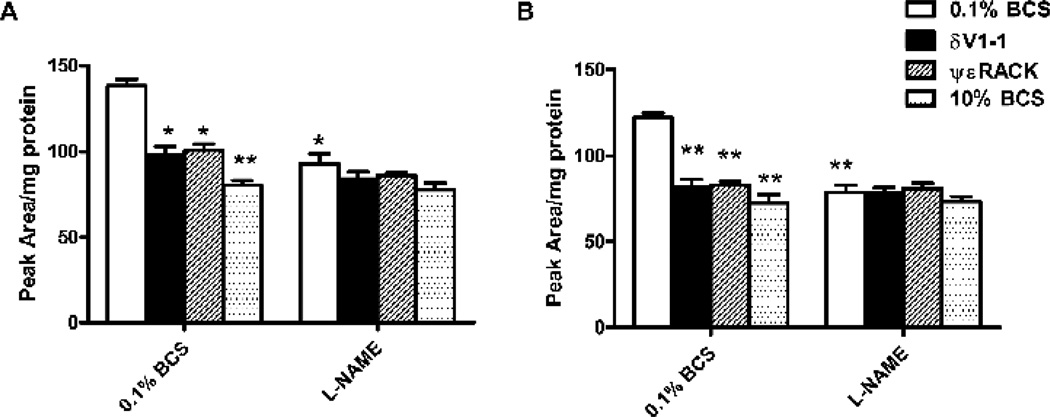

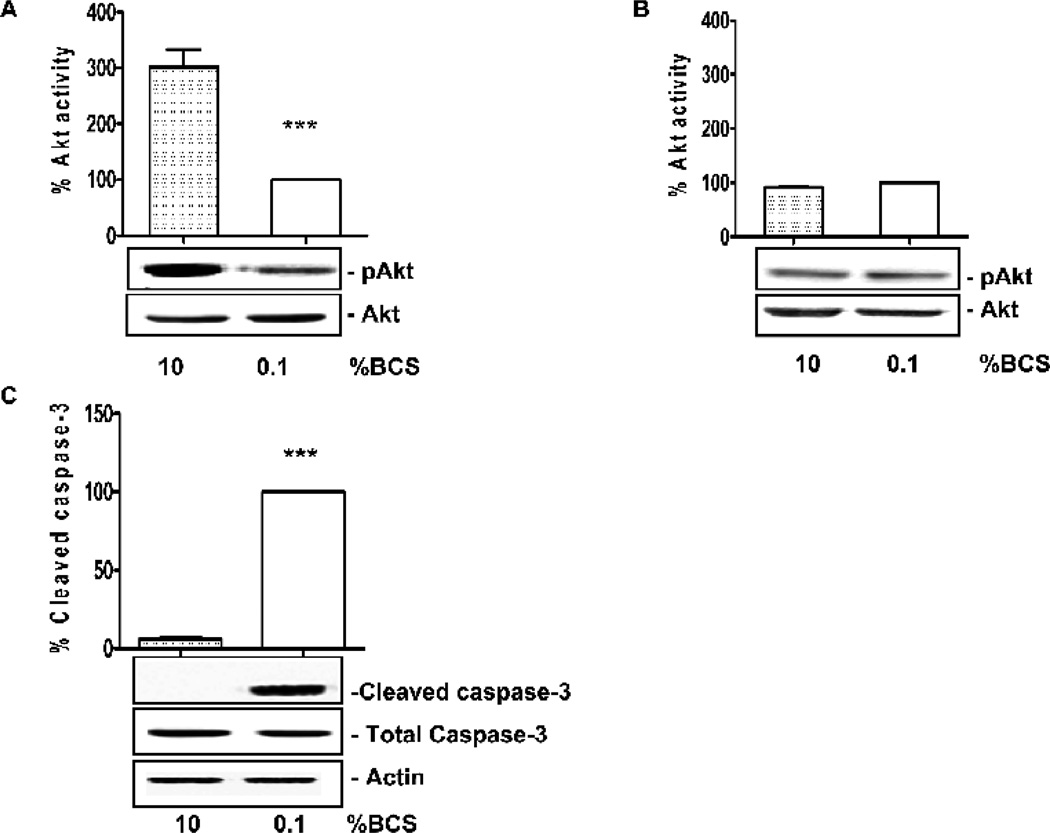

A substantial rise in ROS level was observed in cells exposed to 0.1% BCS at both 15 min and 6 h time points. This rise was significantly reduced by application of 10% BCS, by treating with the δPKC inhibitor or the εPKC activator or by L-NAME treatment (Fig. 1). Akt phosphorylation levels were high in cells treated with 10% BCS at 15 min, and declined substantially at 6 h (Fig. 2A and B). Conversely, Akt activity was markedly reduced in cells exposed to 0.1% BCS either for 15 min or 6 h (Fig. 2A and B) p<0.001 vs. 10% BCS). Activated caspase-3 levels, which were minimal in the 10% BCS group, were about 20 fold higher in cells maintained in 0.1% BCS for 6 h (Fig. 2C, p<0.001 vs. 10% BCS). Therefore, low serum conditions results in an impairment of CVEC as shown by the loss of the survival signal Akt and the enhanced levels of the early pro-apoptotic caspase-3.

Figure 1. δV1-1 or ψεRACK decrease ROS levels in CVEC.

ROS production in CVEC was measured by the DHE/HPLC assay. CVECs were treated with 1 µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK, or 10% BCS, in presence or absence of 200 µM L-NAME in 0.1% BCS, for 15 min (A) or 6 h (B). Results are expressed as peak area/mg protein ± S.D. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs. 0.1% BCS.

Figure 2. Serum deprivation promotes endothelial cell dysfunction.

Akt phosphorylation in serum-deprived CVEC exposed to 0.1% BCS for 15 min (A) or 6 h (B). Total Akt is used for normalization. The graphs represent quantification of gels. Akt activity is expressed as percent ± SD. ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. C. Cleaved caspase-3 in serum-deprived CVEC exposed to 0.1% BCS for 6 h. Actin is used for normalization. Total caspase-3 is shown as control of loading. The graph represents quantification of gels. Caspase-3 activity is expressed as percent vs. 0.1% BCS. ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. The gels shown in this and following figures are representative of three with similar results.

3.2. Serum deprivation modifies the state of δ and e PKC activation in endothelial cells

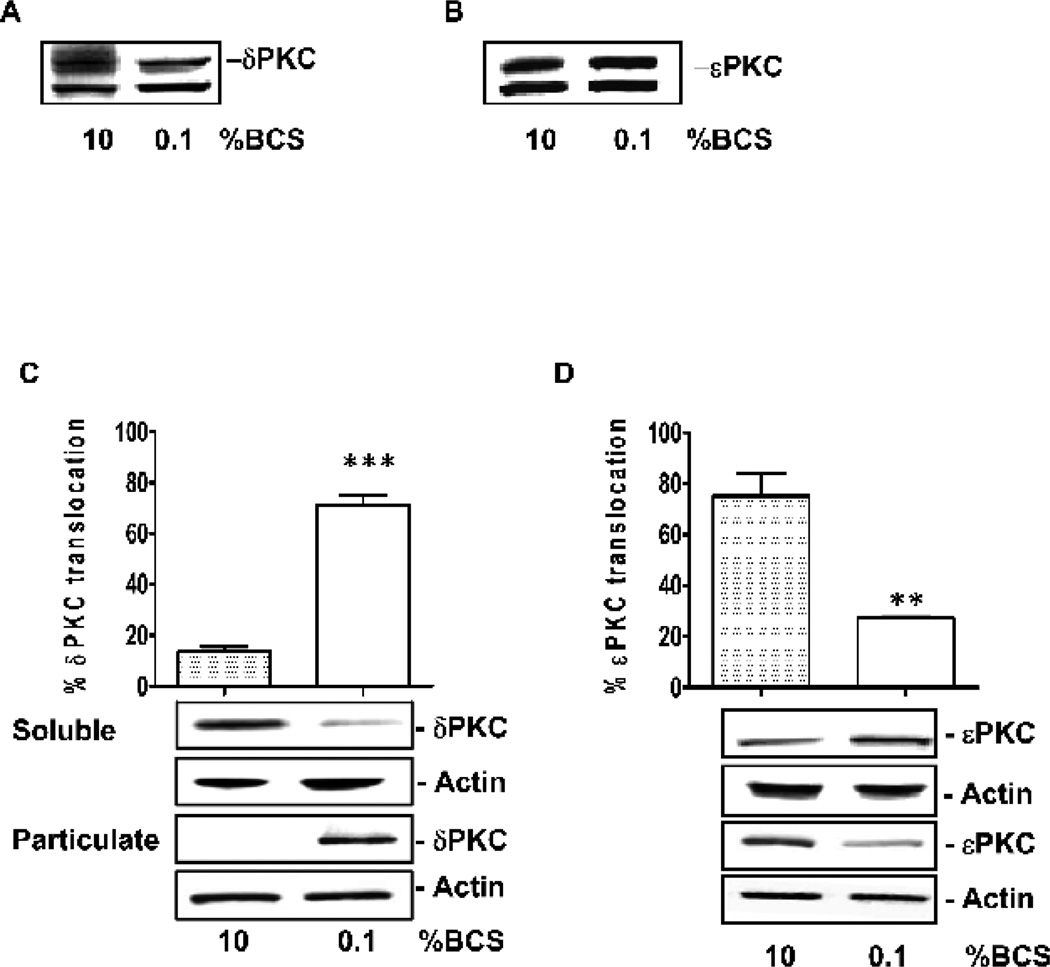

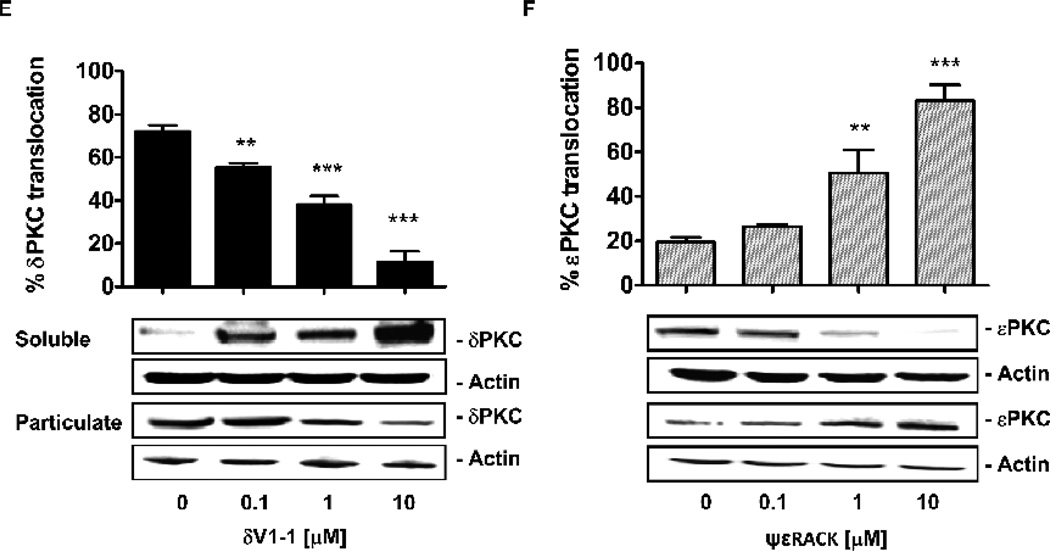

The levels of both PKC isozymes, δ and εPKC, were unaffected by serum concentration in coronary endothelial cells (Fig. 3A and B). However, the intracellular localization of these isozymes, i.e. their activation state [21], changed as a function following treatment with serum. There was a six fold increase in δPKC levels in the particulate fraction when the cells were transferred from high serum to low serum conditions, indicating δPKC activation by serum deprivation (Fig. 3C, p<0.001 vs. 10% BCS). In contrast, there was a ~60% decline in the levels of δPKC in the particulate fraction under the same conditions, consistent with εPKC inactivation by serum deprivation (Fig. 3D, p<0.01 vs. 10% BCS).

Figure 3. Effect of serum on δPKC and εPKC activation.

Expression of δPKC (A) and εPKC (B) in CVEC exposed to 0.1% or 10% BCS. Subcellular distribution of δPKC (C) and εPKC (D) in CVEC exposed to 0.1% or 10% BCS for 15 min. The graphs represent quantification of percent enzyme translocation, calculated as (particulate fraction / particulate fraction + soluble fraction) * 100 ± S.D. **p<0.001 or ***p<0.001 vs. 10% BCS. Translocation of δPKC (E) and εPKC (F) in CVEC exposed to δV1-1 or ψεRACK (0.1-10 µM, 15 min). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. In all blots, total actin is shown as loading control.

δV1-1 treatment inhibited δPKC translocation induced by low serum in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3E, 55 ± 2% at 0.1 µM, p<0.05; 38 ± 4% at 1 µ M, p<0.01 and 11 ± 5% at 10 µ M, p< 0.001 vs. 72 ± 3% at 0.1% BCS). Conversely, treatment with ψεRACK, in low serum, promoted the translocation of the corresponding isozyme from the cytosol to the membrane (Fig. 3F; 26 ± 1 % at 0.1 µM; 50 ± 11% at 1 µM, p<0.01 and 83 ± 7 % at 10 µM, p<0.001 vs. 20 ± 2% when cultured at 0.1% BCS). The effect of the peptides was selective for the corresponding isozyme and did not affect the translocation of other PKC isozymes [12]. Taken together, the data indicate that serum deprivation causes opposite effects on these two PKC isozymes: it promotes δPKC activation and εPKC inactivation; treatments with δV1-1 or ψεRACK reversed the enzyme functional state.

3.3. Inhibition of δPKC or activation of εPKC protects endothelial cells from damage mediated by serum deprivation

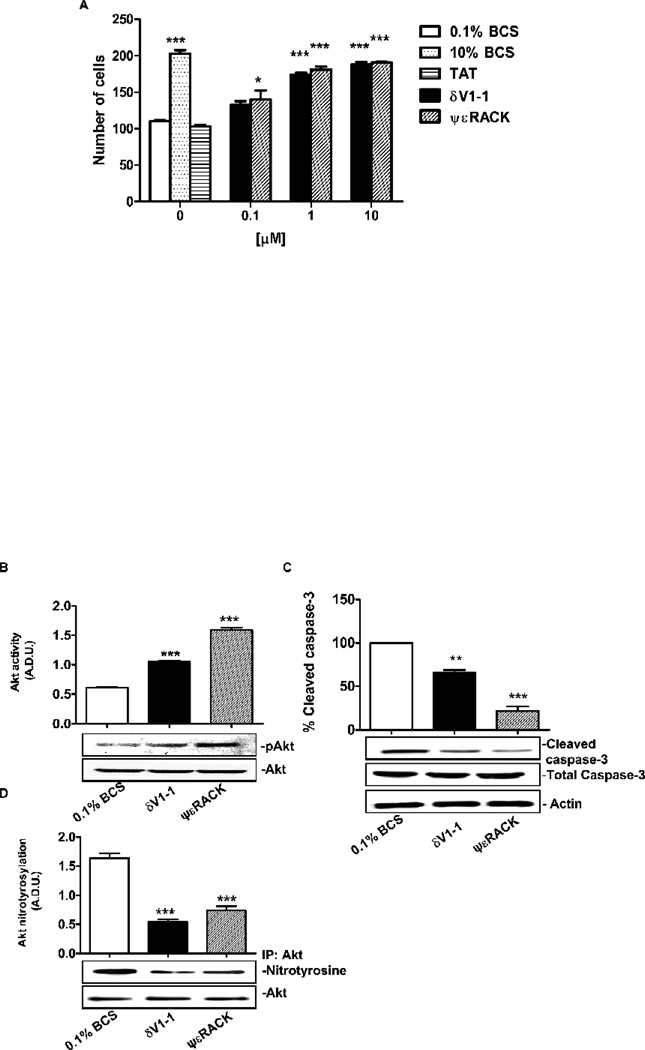

Concomitantly with the changes of δ and εPKC localization, 24 h treatment of CVEC with either δV1-1 or ψεRACK led to a dose-dependent increase in cell number, with maximal effect observed at 1 µM of either PKC regulating peptide (Fig. 4A). At this concentration, δV1-1 or ψεRACK produced an increase in cell number comparable to that induced by 10% BCS (Fig. 4A, p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS). Further, 1 µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK increased Akt phosphorylation by 2 and 3 fold, respectively (Fig. 4B; p<0.001 for δV1-1 and ψεRACK vs. 0.1% BCS), and correspondingly diminished caspase-3 levels (Fig. 4C; p<0.01 and 0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS, respectively). As reported above, these PKC peptide regulators also reduced ROS levels in a fashion comparable to that of L-NAME (Fig. 1), suggesting that eNOS activation correlates with the production of ROS/RNS (reactive nitrogen species) levels, and might be the molecular target of δ and εPKC. As a functional measure of eNOS-mediated ROS/RNS production, we evaluated Akt nitration in CVEC exposed to 0.1% BCS. Indeed, Akt nitrated species were markedly more abundant than the phosphorylated Akt at this time point (Fig. 4B and D). δV1-1 or ψεRACK (1 µM) significantly (p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS) reduced Akt nitration, indicating that δ and εPKC exert opposing effects on peroxynitrite (ONOO−) levels; δPKC activation increases the levels of peroxynitrite whereas εPKC activation decreases them. Consistently, in CVEC cultured with the ONOO− donor SIN-1 (200 µM), the PKC peptides fail to prevent Akt nitration, indicating that the peptides act by preventing ONOO− formation (Fig. 4E and F).

Figure 4. δV1-1 or ψεRACK promote Akt activation and cleaved caspase-3 inhibition.

A. CVEC were serum-deprived for 24 h and then exposed to 10 % BCS or δV1-1 or ψεRACK or TAT in 0.1% BCS for 24 h. Data are reported as number of cells ± S.D. *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. B. Akt activity in CVEC exposed to 1mM dV1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 15 min. The graph represents quantification of gels (Arbitrary Densitometric Units). ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. C. Cleaved caspase-3 in CVEC exposed to 1µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 6 h. The graph represents quantification of gels (percent ± S.D. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS). D. Nitrated-Akt in CVEC treated with 1µM dV1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 15 min. The graph represents quantification of gels (Arbitrary Densitometric Units). ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. Nitrated (E) and phosphorylated (F) Akt were measured after treatment of SIN-1 (200 µM, 15 min) in the presence or absence of both peptides. Results are reported as A.D.U. (Arbitrary Densiometric Unit). *p<0.05 and **<p0.01 vs. 10% BCS. G. Micro-carrier-coated CVEC exposed to 10% BCS, or 1mM dV1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS and in the presence or absence of 10 µM LY294002 for 3 days. Cell sprouting is expressed as the mean of grid units covering the entire surface occupied by sprouting. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs. 0.1% BCS; ##p<0.01 vs. δV1-1; §§p<0.01 vs. ψεRACK.

The relevance of the PKC modulation of ROS/RNS levels and Akt signaling, was further highlighted by the influence of the peptide regulators of δ and εPKC on endothelial cell sprouting, an assay which represents the angiogenic potential of the endothelium. CVEC were embedded on microcarrier beads and cultured in 0.1% BCS for 24 h. Addition of either δV1-1 or ψεRACK caused a striking increase of pseudo-capillary formation relative to control (Fig. 4G, p<0.01 and p<0.05 vs. 0.1% BCS, respectively). Treatment with the LY294002, an inhibitor of the PI3-kinase upstream to Akt, inhibited sprouting formation induced by δV1-1 or ψεRACK (Fig. 4G, p<0.01 vs. both peptides), further documenting the importance of Akt as a target of these two PKC isozymess. Therefore, δPKC and εPKC exert opposing effects; activation of δPKC inhibits and activation of εPKC increases serum starvation-induced pseudo-capillary formation.

3.4. δ and ε PKC regulate ONOO− levels through the modulation of eNOS activity

Given the pro-survival properties of these two PKC isozymes, and in particular their effect on Akt nitration, we examined their effect on eNOS activity. We focused on post-translational regulation of eNOS activity by assessing the main phosphorylation sites involved in regulation of NO production, i.e. Ser1179, Ser635, Thr497 and Ser116. Other studies indicated that NO generation depends on the simultaneous phosphorylation of Ser1179 or Ser635, and de-phosphorylation of Thr497 and Ser116 [5]. Ser635 is reported to be involved in maintaining increased eNOS activity after the initial activation by Ca2+ influx and/or Ser1179 phosphorylation, which, conversely, is rapidly phosphorylated by a variety of stimuli and controls both basal and stimulated NO synthesis [5].

In low serum, eNOS was weakly phosphorylated at Ser1179 (activator site), and at Thr497 and Ser116 (inhibitory sites), suggesting a partial activity of the enzyme. Brief exposure of serum deprived-CVEC to either δV1-1 or ψεRACK (1 µM, 15 min) resulted in a significant de-phosphorylation of Ser1179, and a marked phosphorylation of Thr497 and Ser116, the inhibitory sites (Fig. 5A, p<0.001 for δV1-1 or ψεRACK vs. 0.1% BCS), suggesting inactivation of eNOS by these treatments. Interestingly, at 10% BCS, at 10% BCS, a condition endowed with great antioxidant activity [22], the phosphorylation pattern of eNOS indicated enzyme activation; Ser1179 phosphorylation increased and Thr497 and Ser116 phosphorylation decreased. Phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser635 was unaffected under these conditions by either peptide as well by 10% BCS (data not shown).

Figure 5. δV1-1 and ψεRACK modulate eNOS phosphorylation and activity.

A. Phosphorylation of eNOS on Ser1179, Thr497, Ser116 or Ser635 in CVEC exposed to 10% BCS, or 1 µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 15 min. Total eNOS is used for normalization. The graph represents quantification of gels (Arbitrary densitometric units). ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. B. cGMP production in CVEC treated with 10% BCS, or 1 µM δ V1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 15 min. Data are expressed as (pg/ml)/mg protein. **p<0.01 vs. 0.1% BCS. or (C) eNOS phosphorylation (see above for phosphorylation sites) in CVEC exposed to 10% BCS, or 1 µM δV1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 6h. Total eNOS is used for normalization. The graph represents quantification of gels (Arbitrary densitometric units). **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. D. cGMP production in CVEC treated with 10% BCS, or 1 µM δ V1-1 or ψεRACK in 0.1% BCS for 6 h. Data are expressed as (pg/ml)/mg protein. #p<0.05 and ##p<0.01 vs. 0.1% BCS.

Six hours after serum deprivation, a different phosphorylation pattern was noted. At this time point, cells treated with δV1-1 or ψεRACK peptides or with 10% BCS exhibited a similar phosphorylation pattern. In fact, whereas the Ser1179 phosphorylation was unaffected by either peptides or by 10% BCS (data not shown), phosphorylation of Thr497 and Ser116 were significantly reduced relative to that observed in low serum (Fig. 5C, p<0.001 and p<0.01 vs. 0.1% BCS, respectively), and phosphorylation of eNOS Ser635 increased (Fig. 5C, p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS). Overall this phosphorylation pattern is indicative of eNOS activation.

Consistent with the eNOS phosphorylation state, 15 min after administration either PKC regulator reduced eNOS activity by 40%, as measured by cGMP production, whereas 10% BCS increased it (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained with L-NAME (Fig. 5B) In contrast, after 6 h treatment, either regulator elicited an increase in eNOS activity that was similar to that observed in the presence of 10% BCS (Fig. 5D, p<0.01 for δV1-1, and p<0.05 for ψεRACK vs. 0.1% BCS). cGMP production continued to decline in cells maintained in 0.1% BCS, as in L-NAME, for up to 6 h (Fig. 5B and D), indicative of progressive endothelial damage due to serum deprivation.

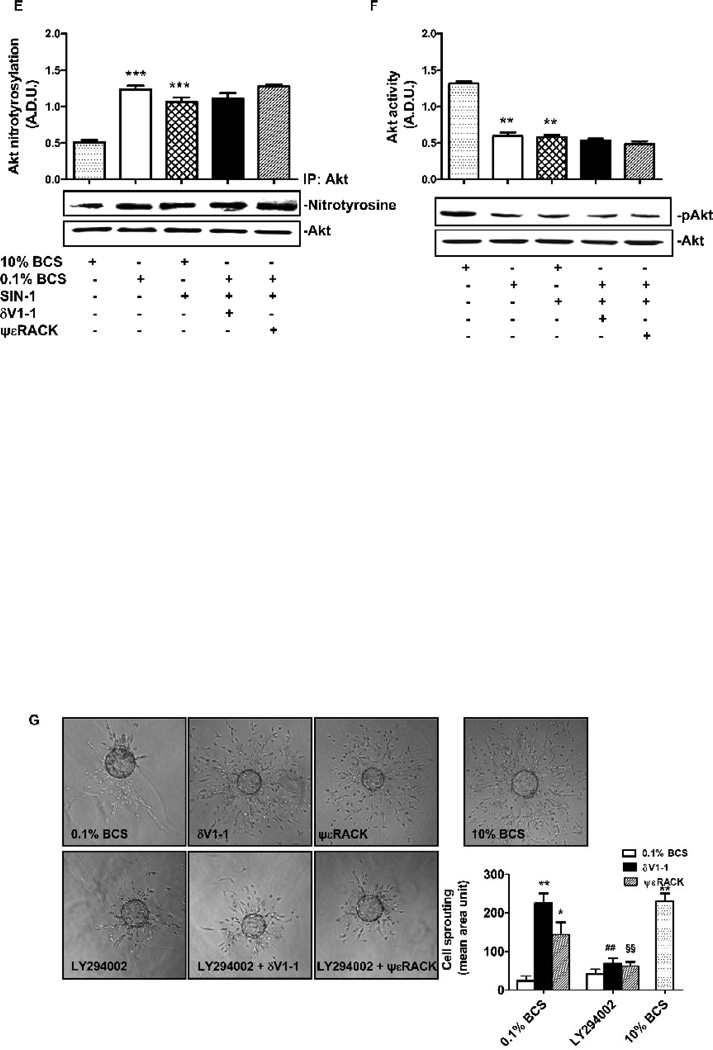

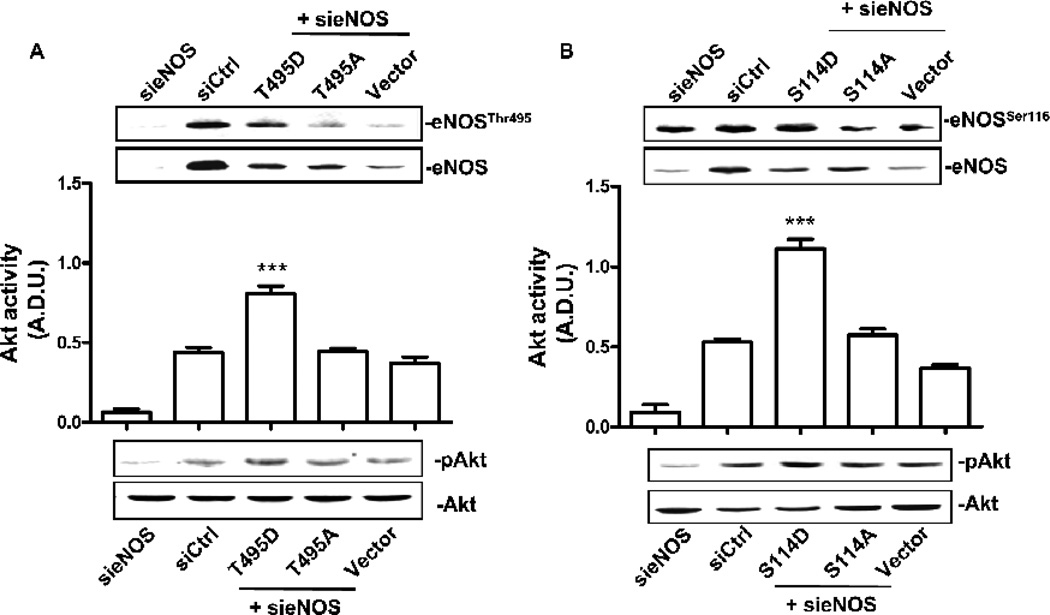

3.5. Transient inhibition of eNOS activity rescues endothelial cells from apoptosis induced by serum deprivation

To document the role of eNOS activity on Akt phosphorilation in serum deprivation, we produced transfectants in which eNOS was consitutively inhibited or activated. CVEC were silenced for bovine eNOS and transfected with plasmids mimicking the phosphorylated forms of human eNOS at Ser114- or Thr495-inhibitory sites (S114D and T495D, respectively) and the respective de-phosphorylated/active ones (S114A and T495A, respectively). CVEC bearing S114D and T495D eNOS mutants, produced low levels of cGMP and ROS/RNS (see data in Fig.6 legend), whereas S114A and T495A were not different from the control. Exposure of S114D and T495D eNOS mutants to 0.1% BCS for 24 h resulted in increased Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 6A and B), demonstrating the existence of a direct link between eNOS and Akt activity, i.e. eNOS inhibition correlates with Akt activation in serum deprived endothelial cells.

Figure 6. eNOS inhibition controls Akt activity.

CVEC were silenced for bovine eNOS and transfected with the phospho-mimetic or the dephospho-mimetic form of human eNOS in Thr495 (A) or Ser114 (B) (T495D and T495A or S114D and S114A, respectively). To verify cell transfection, western blot for eNOS Thr495 (A, upper panels) or Ser114 phosphorylation (B, upper panels) was carried out and normalized for total eNOS In these cells cGMP levels were: (pg/mg protein): 3.5 ± 0.4 for S114D and 3.3 ± 0.2 for T495D, p<0.01 vs. Vector 7.2 ± 0.3; 7.5 ± 0.2 for S114A and 6.9 ± 0.4 for T495A) of and ROS/RNS levels were (peak area/mg protein): 96 ± 4 for S114D and 98 ± 2 for T495D, p<0.01 vs. Vector 135 ± 3; 129 ± 4 for S114A and 132 ± 4 for T495A). The graphs represent quantification of phospho-Akt/total Akt gels (Arbitrary Densitometric Units); ***p<0.001 vs. Vector and ##p<0.01 vs. T495D or S114D respectively. C. Akt activity in CVEC exposed to L-NAME (15 min, 200 µM). The graph represents quantification of gels (Arbitrary Densitometric Units).**p<0.01 vs. 0.1% BCS D Cleaved caspase-3 in CVEC exposed to L-NAME (6 h, 200 µM) in 0.1% BCS. The graph represents quantification of gels (percent ± S.D.). ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. E Nitrated-Akt in CVEC treated with L-NAME (15 min, 200 µM) in 0.1% BCS. The graph represents quantification of gels (Arbitrary Densitometric Units). ***p<0.001 vs. 0.1% BCS. In the presence of L-NAME the number of cells was: 153 ± 6, 200 µM L-NAME, vs. 0.1% BCS 105 ± 4; p<0.01.

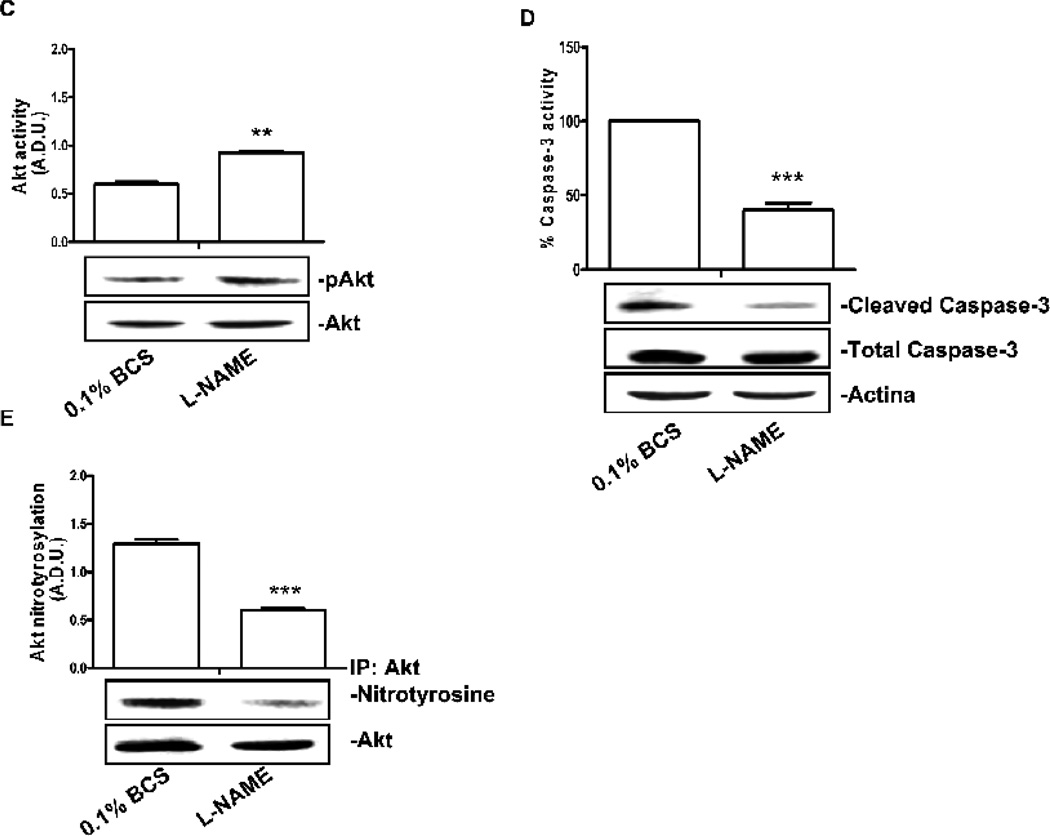

The above experiments further indicated that, during serum deprivation, uncontrolled eNOS activity negatively regulate Akt and cell survival. To conclusively demonstrate that the protective effect of the PKC peptide during serum deprivation was mediated by the transient inhibition of eNOS activity, in cells serum deprived for 24 h, we measured Akt and caspase-3 activation following a 15 min treatment with L-NAME (200 µM). L-NAME treatment doubled Akt phosphorylation, decreased Akt nitration and the activated-caspase-3 levels (Fig. 6C, D and E). Consistently, when L-NAME was given to CVEC during the 24 h starvation time, the number of cell significantly increased (see legend Fig. 6) with an effect comparable to that produced by PKC agonists (see Fig. 4A)

In summary, the data demonstrate that in oxidative stress condition uncontrolled eNOS activation negatively regulates Akt phosphorylation affecting cell survival. Conditions in which eNOS is constitutively inhibited or pharmacologically modulated, either as by L-NAME or PKC ligands, Akt nitration is prevented restoring Akt phosphorylation and cell survival.

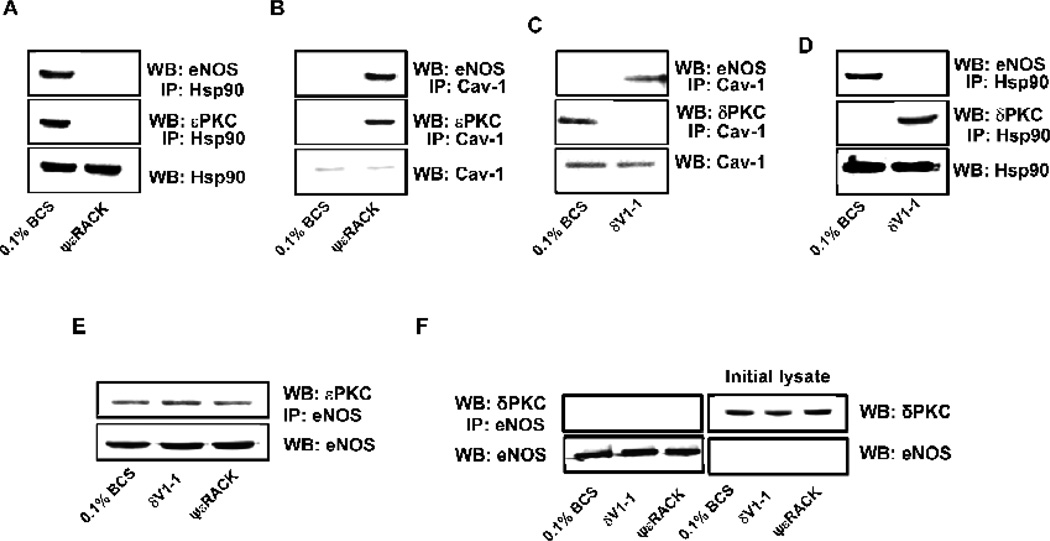

3.6. δPKC or εPKC control eNOS interaction with Cav-1 and Hsp90

Because eNOS activity is also regulated by interaction with membrane or cytoplasmic proteins, we also determined whether eNOS interaction with the inhibitory Cav-1 and the stimulatory Hsp90 proteins [4] is altered in response to regulation of d or ePKC. In low serum, at 15 min, eNOS was associated with Hsp90 and with εPKC (Fig. 7A), whereas δPKC was associated with Cav-1 (Fig. 7C). εPKC activation with ψεRACK (1 µM, 15 min) shifted the eNOS/εPKC complex to Cav-1 (Fig. 7B), as did δPKC inhibition with δV1-1 (Fig. 7C). These data indicate that either δPKC inhibition or εPKC activation promoted inactivation of eNOS by sequestering it on the caveolae.

Figure 7. δV1-1 and ψεRACK modulate eNOS protein-protein interaction.

CVEC were treated with ψεRACK (15 min, 1µM), then immunoprecipitated for anti-Hsp90 (A) or Cav-1 (B) and immunoblotted for eNOS or εPKC. CVEC were treated with δV1-1 (15 min, 1 µM), then immunoprecipitated with anti-Cav-1 (C) or Hsp90 (D) and immunoblotted for δPKC or eNOS. Cells were treated with δV1-1 or ψεRACK (15 min, 1µM) then immunoprecipitated for anti-eNOS and immunoblotted for εPKC (E) or δPKC (F). Also in panel F are levels of δPKC and eNOS in the respective initial lysate.

From the above results, eNOS appeared to be in complex with εPKC (Fig. 7A and E). To confirm this interaction, we carried out co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Either ψεRACK or δV1-1 treatment resulted in an increased association of eNOS with εPKC (Fig. 7E), but not with δPKC (Fig. 7F), suggesting a direct role of εPKC in controlling the eNOS phosphorylation status, possibly through phosphorylation on Thr497 and Ser116 (see Fig. 5A).

4. Discussion

The isozyme-specific peptide regulators δV1-1 and ψεRACK, which inhibit δPKC and activate εPKC, respectively, have been the focus of research interest for the protective properties they exert on cardiac and brain vascular ischemic diseases [7, 12–14]. Here, we describe their actions on endothelial dysfunction using coronary endothelial cells cultured in oxidative stress environment produced by nutrient deprivation. We show that these PKC isozyme-specific peptide regulators protect the endothelium from the severe damage induced by nutrient withdrawal in terms of function (cell growth, angiogenic potential), integrity of cell survival signals (eNOS, caspase-3 and Akt activities) and intracellular localization of these signaling enzymes. The main finding of this work relates to the involvement of eNOS in the endothelial protective mechanism. In the oxidative stress environment used in this study, eNOS was activated, leading to a high output of ROS and RNS, documented, in part, by increased nitration of the pro-survival enzyme, Akt. Akt nitration, in turn, caused arrest of cell growth, inhibition of capillary sprouting, as well as activation of the pro-apoptotic caspase-3.

Application of either the δPKC-selective inhibitor or the εPKC-selective activator to damaged endothelial cells sharply reduced the initial over-production of ROS and the increase in activated (cleaved) caspase-3, fully restoring the ability of the cells to grow and exhibit angiogenic phenotype. Of note is the magnitude (>100 fold), and the persistence (up to three days) of the effects exerted by δV1-1 or ψεRACK treatments on vessel formation. Also worth of note is the inhibition of ROS production by L-NAME, an inhibitor of eNOS.

eNOS activity, is regulated by a wide repertoire of post-translational modifications [4–5], including multiple phosphorylation at specific sites as the main determinant of enzyme activation state [4–5]. We focused on phosphorylation of the stimulatory Ser1179, Ser635 and on phosphorylation of the inhibitory Thr497, and Ser116 in response to either δPKC inhibition or εPKC activation. The largest changes occurred at the inhibitory sites Thr497 and Ser116, which, after exposure to the PKC regulating peptides, showed a transient increase in phosphorylation, followed by a significant de-phosphorylation. Conversely, among the stimulatory sites, Ser635 was the only site that was phosphorylated upon prolonged exposure of cells to δV1-1 or ψεRACK peptides, whereas Ser1179 was either de-phosphorylated or unchanged depending on the length of exposure resulting in transient eNOS inhibition then reverted in enzyme activation. NO/cGMP production paralleled the above described PKC peptide-mediated phosphorylation/de-phosphorylation state of eNOS. Following 24 h of serum deprivation, we observed a transient decline in NO/cGMP production in response to PKC peptide regulators, followed by robust enhancement (150% over control).

In coronary endothelium exposed to serum starvation, Akt signal is heavily affected. The nitrated Akt species prevailed over the phosphorylated ones, a trend promptly reversed by co-incubation with the PKC ligands, and are responsible for the reduced cell survival. The nitrated Akt results from uncontrolled eNOS activity and the ensuing output of ROS/RNS [23]. In fact, inhibiting NO/RNS output, as in Ser114 or Thr495 transfectants, or by L-NAME, Akt nitration is prevented and Akt can be activated. Consistent with the conclusion that the PKC ligands modulate the NO/ONOO− production by affecting eNOS activity, rather than scavenging ONOO− levels, the nitration of Akt induced by SIN-1, is not affected by either the δV1-1 or ψεRACK peptides [23]

The intricate relationship between eNOS and these two PKC enzymes is likely dependent on the cell type and on the pathophysiological conditions. In aortic endothelial cells, PKC activation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) exerts a negative control on eNOS [5] through Thr497 phosphorylation. We show here that the use of the εPKC inhibitor or εPKC activator reveals distinct and opposing actions of these two isozymes on eNOS activity in coronary microvascular endothelial cells (Fig. 9). In other studies, εPKC mediates eNOS Ser1177 phosphorylation and VEGF-induced Akt [24] in HUVEC endothelial cells, whereas δPKC inhibition enhances endothelial cell survival during hypoxia [25], and decreases eNOS expression through inhibition of Akt phosphorylation [26] in lung endothelial cells.

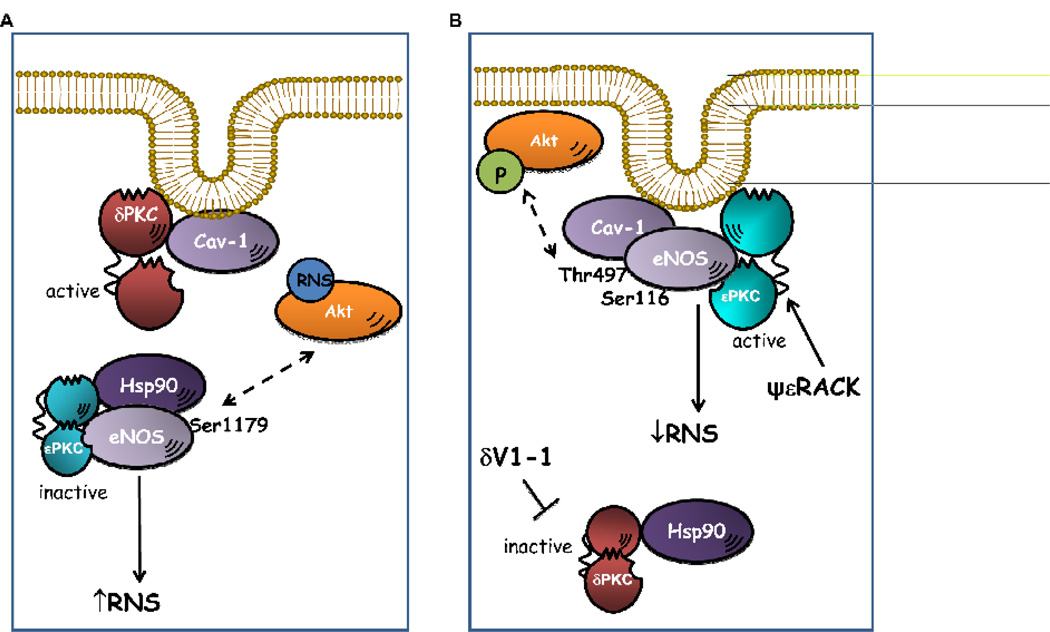

Although we found similar effect of δV1-1 and ψεRACK on endothelial function, differences emerged when studying the effects of these PKC regulators on eNOS localization and compartmentalization. Serum deprivation of endothelial cells induced a large translocation of δPKC to the cell particulate fraction leading to enzyme activation (Fig. 8, panel A) and its association with Cav-1, and a concomitant increase of eNOS activation and interaction with Hsp90. Inhibition of δPKC translocation with δV1-1 displaces it from Cav-1, which may become available for eNOS docking and inactivation, a process which restrains the unregulated toxic output of free radicals. Conversely, nutrient deprivation inactivates εPKC by shifting the enzyme to the soluble cell compartment in which it complexes with Hsp90 and eNOS. ψεRACK promotes the translocation of the εPKC/eNOS complex to Cav-1, inhibiting eNOS activity possibly through εPKC-mediated phosphorylation of Thr497 and Ser116 (Fig. 8, panel B). According to this mechanism, inhibition of δPKC by δV1-1 exerts a permissive, albeit important action, disclosing the inherent beneficial effect of εPKC. The proposed mechanism explains the temporal pattern of functional endothelial recovery promoted by these isozyme-specific PKC regulators, and may account for the beneficial effects noted in ischemic conditions by the combined delivery of the compounds [13, 27].

Figure 8. Schematic model of relationship between eNOS and PKC isoforms in low serum and after treatment with δV1-1 or ψεRACK.

A. In nutrient deprivation conditions δPKC is activated and associated with Cav-1, while inactive εPKC is localized in the cytoplasm and associated with eNOS and Hsp90. In this condition, eNOS is activated, high levels of ROS/RNS are produced, and Akt is nitrated. B. Treatment with δV1-1 or with ψεRACK shifted εPKC to the cytoplasm and εPKC translocates to the membrane, respectively. Active ePKC associates with eNOS and Cav-1, and promotes inhibition of eNOS by increasing eNOS phosphorylation at Thr497 and Ser116 sites. Inhibition of eNOS results in decreased ROS and RNS production and increased phosphorylation of Akt.

In conclusion, eNOS plays a major role in the rescuing action exerted by δV1-1 and ψεRACK on endothelial dysfunction. Under oxidative stress, eNOS activity appears uncontrolled, leading to production of high levels of NO and, consequently, contributing to ROS/RNS production and endothelial dysfunction. We demonstrate that the stimulation of εPKC causes eNOS phosphorylation at Thr497 and Ser116 inhibitory sites, thus restraining uncontrolled eNOS activity, and the ensuing ROS/RNS formation induced by nutrient withdrawal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Ingrid Fleming (Department of Cardiovascular Physiology, University of Frankfurt, Germany) for the eNOS mutant plasmids, Drs. Grant R. Budas and Marie-Helene Disatnik (Department of Chemical and Systems Biology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA) for technical assistance and synthesis of the δV1-1 and ψεRACK peptides. This work is supported by the Progetto Ordinario-Ministero della Salute, by Vigoni Program (Ateneo Italo Tedesco) and by EU project EICOSANOX FP6 funding (LSHM-CT-2004- 0050333). This publication reflects only the author’s views.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

DM-R is the founder and share-holder of KAI Pharmaceuticals. However, none of the work in her laboratory is in collaboration with or supported by the company. The other authors have no conflicts of interest pursuant to the current work.

References

- 1.Forstermann U. Janus-faced role of endothelial NO synthase in vascular disease: uncoupling of oxygen reduction from NO synthesis and its pharmacological reversal. Biol Chem. 2006;387(12):1521–1533. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griendling KK. Novel NAD(P)H oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Heart. 2004;90(5):491–493. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.029397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koppenol WH, Moreno JJ, Pryor WA, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite, a cloaked oxidant formed by nitric oxide and superoxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5(6):834–842. doi: 10.1021/tx00030a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudzinski DM, Michel T. Life history of eNOS: partners and pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(2):247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mount PF, Kemp BE, Power DA. Regulation of endothelial and myocardial NO synthesis by multi-site eNOS phosphorylation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42(2):271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming I, Schulz C, Fichtlscherer B, Kemp BE, Fisslthaler B, Busse R. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates the insulin-induced activation of the nitric oxide synthase in human platelets. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(5):863–871. doi: 10.1160/TH03-04-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bright R, Steinberg GK, Mochly-Rosen D. DeltaPKC mediates microcerebrovascular dysfunction in acute ischemia and in chronic hypertensive stress in vivo. Brain Res. 2007;1144:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakano A, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Ischemic preconditioning: from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;86(3):263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inagaki K, Churchill E, Mochly-Rosen D. Epsilon protein kinase C as a potential therapeutic target for the ischemic heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70(2):222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochly-Rosen D. Localization of protein kinases by anchoring proteins: a theme in signal transduction. Science. 1995;268(5208):247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.7716516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souroujon MC, Mochly-Rosen D. Peptide modulators of protein-protein interactions in intracellular signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16(10):919–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt1098-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Hahn H, Wu G, Chen CH, Liron T, Schechtman D, Cavallaro G, Banci L, Guo Y, Bolli R, Dorn GW, Mochly-Rosen D. Opposing cardioprotective actions and parallel hypertrophic effects of delta PKC and epsilon PKC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(20):11114–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191369098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inagaki K, Hahn HS, Dorn GW, Mochly-Rosen D. Additive protection of the ischemic heart ex vivo by combined treatment with delta-protein kinase C inhibitor and epsilon-protein kinase C activator. Circulation. 2003;108(7):869–875. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081943.93653.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeno F, Inagaki K, Rezaee M, Mochly-Rosen D. Impaired perfusion after myocardial infarction is due to reperfusion-induced deltaPKC-mediated myocardial damage. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73(4):699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schelling ME, Meininger CJ, Hawker JR, Jr., Granger HJ. Venular endothelial cells from bovine heart. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(6 Pt 2):H1211–H1217. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.6.H1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziche M, Parenti A, Ledda F, Dell’Era P, Granger HJ, Maggi CA, Presta M. Nitric oxide promotes proliferation and plasminogen activator production by coronary venular endothelium through endogenous bFGF. Circ Res. 1997;80(6):845–852. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zielonka J, Hardy M, Kalyanaraman B. HPLC study of oxidation products of hydroethidine in chemical and biological systems: ramifications in superoxide measurements. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(3):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donnini S, Solito R, Giachetti A, Granger HJ, Ziche M, Morbidelli L. Fibroblast growth factor-2 mediates Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angiogenesis in coronary endothelium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319(2):515–522. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.108803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnini S, Cantara S, Morbidelli L, Giachetti A, Ziche M. FGF-2 overexpression opposes the beta amyloid toxic injuries to the vascular endothelium. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(7):1088–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, Wright LR, Chen CH, Oliver SF, Wender PA, Mochly-Rosen D. Molecular transporters for peptides: delivery of a cardioprotective epsilonPKC agonist peptide into cells and intact ischemic heart using a transport system, R(7) Chem Biol. 2001;8(12):1123–1129. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraft AS, Anderson WB. Phorbol esters increase the amount of Ca2+, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase associated with plasma membrane. Nature. 1983;301(5901):621–623. doi: 10.1038/301621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roche M, Rondeau P, Singh NR, Tarnus E, Bourdon E. The antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FEBS Letters. 2008;582:1783–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou MH, Hou XY, Shi CM, Nagata D, Walsh K, Cohen RA. Modulation by peroxynitrite of Akt- and AMP-activated kinase-dependent Ser1179 phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):32552–32557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Differential regulation of VEGF signaling by PKC-alpha and PKC-epsilon in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(5):919–924. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shizukuda Y, Tang S, Yokota R, Ware JA. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell migration and proliferation depend on a nitric oxide-mediated decrease in protein kinase Cdelta activity. Circ Res. 1999;85(3):247–256. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sud N, Wedgwood S, Black SM. Protein kinase Cdelta regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression via Akt activation and nitric oxide generation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294(3):L582–L591. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00353.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Tanaka M, Terry RD, Mokhtari GK, Inagaki K, Koyanagi T, Kofidis T, Mochly-Rosen D, Robbins RC. Suppression of graft coronary artery disease by a brief treatment with a selective epsilonPKC activator and a deltaPKC inhibitor in murine cardiac allografts. Circulation. 2004;110(11 Suppl 1):II194–II199. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138389.22905.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]