Abstract

Approximately 15% to 20% of women have been victims of rape and close to a third report current rape-related PTSD or clinically significant depression or anxiety. Unfortunately, very few distressed rape victims seek formal help. This suggests a need to develop alternative ways to assist the many distressed victims of sexual violence. Online treatment programs represent a potentially important alternative strategy for reaching such individuals. The current paper describes a pilot evaluation of an online, therapist-facilitated, self-paced cognitive behavioral program for rape victims. Five college women with current rape-related PTSD were recruited to complete the From Survivor to Thriver (S to T) program in a lab setting over the course of 7 weeks. After completing the program, 4 participants reported clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms and no longer met criteria for PTSD. All participants reported clinically significant reductions in vulnerability fears and 4 reported significant reductions in negative trauma-related cognitions. Implications of the results for further development of the S to T program and how clinicians could utilize this program in treating rape-related PTSD are discussed.

Keywords: sexual assault, online treatment, cognitive-behavioral therapy, web-based therapy

The experience of rape, defined as unwanted sexual activity obtained by threat, force, or the assault of a victim incapable of consenting, remains a significant public health problem (Koss et al., 2007). Research consistently supports that between 13% and 20% of women have had at least one experience of rape in adolescence or adulthood (e.g., Cloutier, Martin, & Poole, 2002; Kilpatrick, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1998; Littleton, Grills-Taquechel, & Axsom, 2009; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004). The experience of rape is also often associated with significant and persistent psychological distress. For example, community studies have found that up to 49% of rape victims develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), up to 38% meet criteria for current major depression, and up to 34% meet criteria for another anxiety disorder (Boudreaux, Kilpatrick, Resnick, Best, & Saunders, 1998; Breslau et al., 1998; Frank & Anderson, 1987; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). Similarly, surveys of college women who have experienced rape find that approximately 25% have current rape-related PTSD (Clum, Calhoun, & Kimerling, 2000; Kahn, Jackson, Kully, Badger, & Halvorsen, 2003; Littleton & Henderson, 2009).

Cognitively focused interventions have strong empirical support with regard to reducing PTSD and distress among victims of rape and other forms of interpersonal trauma (e.g., Chard, 2005; Kubany, Hill, & Owens, 2003; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002; Resick & Schnicke, 1992). While these interventions may include an exposure component, they focus on cognitive restructuring of trauma-related cognitions, such as cognitions related to self-blame for the assault, thoughts of low self-worth, and cognitions regarding a lack of trust in others. These interventions have been shown to be as effective as exposure-based treatment for PTSD (Resick et al., 2002). In addition, a recent evaluation of cognitively based therapy for rape victims supported that inclusion of an exposure component was not necessary for effective treatment (Resick et al., 2008). Indeed, this study found that individuals who only received cognitively based treatment experienced greater improvements in PTSD symptoms than women whose treatment included a written trauma account component (Resick et al., 2008).

Although effective trauma treatments exist, many distressed victims unfortunately do not seek out mental health services or delay seeking services for many years, often due to feelings of shame or self-blame (e.g., Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991; Resick & Schnicke, 1992). Indeed, studies find that fewer than 25% of rape victims have disclosed their experience to some type of mental health professional (Beebe, Gulledge, Lee, & Replogle, 1994; Littleton, 2010). Victims’ frequent reluctance to seek out individual therapy suggests a need to find alternative ways to reach the many victims in need of mental health services. One potential way to reach these victims is through online-administered treatment. Indeed, several online-administered treatments for trauma have been developed in recent years, with promising evidence for their efficacy reported. Lange and colleagues conducted two evaluations of an email-based narrative exposure treatment. The first study was a pretest/posttest comparison among 20 college students experiencing bereavement or interpersonal violence (e.g., robbery), and found large changes in PTSD from pre- to posttesting (d=1.5; Lange et al., 2000). They then compared the treatment to wait-list in a community sample experiencing bereavement or family events (e.g., divorce; n=69 intervention, n=32 wait-list) and found that the online program was superior to wait-list (d=1.3) at reducing PTSD (Lange et al., 2003). A recent evaluation with a second research group examined the efficacy of this program compared to a wait-list in a community sample (n=96) who primarily experienced bereavement or sexual trauma, and similarly found large reductions in PTSD (ds = 1.0 − 1.4) and depression (d=1.2), which were maintained for 1.5 years (Knaevelsrud & Maercker, 2007, 2010). Hirai and Clum (2005) compared an online self-help cognitive-behavioral program to wait-list among 27 college students who had primarily experienced a car accident or interpersonal trauma. The program also included minimal therapist contact in the form of prompting to complete the program, as well as computer-generated feedback. Individuals in the program experienced greater reductions in anxiety (d=0.9), depression (d=1.2), and PTSD (d=0.8) than individuals in the wait-list condition. Finally, Litz, Engel, Bryant, and Papa (2007) developed an exposure-based, online, therapist-facilitated CBT program for PTSD. The program included two face-to-face counseling sessions and a phone session. A total of 24 Department of Defense employees with current PTSD in connection to 9/11 or military service completed the program and outcomes were compared to individuals completing a psychoeducational online program (n=21). The exposure program produced superior outcomes at reducing PTSD, d=0.95, and depression, d=1.03.

While these studies support that online interventions for traumatic experiences can be efficacious, they have a number of limitations that should be noted. First, several of these studies excluded individuals with clinically significant depressive symptoms (Knaevelsrud & Maercker, 2007; Lange et al., 2000; Lange et al., 2003), thus likely excluding many of the most distressed victims. Two studies also included individuals who did not meet criteria for PTSD, and thus did not only include individuals with clinically significant levels of distress (Hirai & Clum, 2005; Lange et al., 2000). The Lange and colleagues (2003) study also had a rather high dropout rate of 36% from the intervention; of note, individuals most often reported dropping out because of difficulties completing the intervention (providing written narratives of their stressful or traumatic experience) without in-person therapist support. In addition, two studies excluded individuals with histories of sexual abuse (Hirai & Clum, 2005; Lange et al., 2003), thus excluding many rape victims given that they also frequently have histories of childhood sexual abuse (Littleton et al., 2009). Finally, none of the content of the extant online interventions were tailored to the specific needs of rape victims.

In an attempt to address these limitations, the From Survivor to Thriver (S to T) program was created. This program is an online, cognitive behavioral, therapist-facilitated program with content tailored to address specific difficulties often reported by rape victims, including thoughts of self-blame, difficulties with trust and intimacy, and personal safety concerns. The S to T program includes a number of strategies previously utilized in successful in-person interventions for rape victims, such as cognitive restructuring techniques and relaxation exercises. The program also leverages many of the potential advantages of online interventions such as the inclusion of multiple media (e.g., video and audio clips) and integration of written feedback to interactive exercises by program therapists. Finally, the program includes written examples of women utilizing the skills presented in the program; these are drawn from the clinical experiences of the first and fourth authors, both of whom have worked with victims of sexual violence for over a decade.

Method

Participants

Five women enrolled as students at a large southeastern U.S. university participated in the pilot study. Participants were recruited through fliers posted around campus and through an announcement on a psychology department research management website. Participants all self-identified as European American and were between the ages of 18 and 20 years. All participants had experienced at least one rape since the age of 14. Additionally, all participants currently met criteria for rape-related PTSD, as determined via initial screening interview. It should be noted that two additional women were screened but were not eligible to participate. One woman was excluded due to significant suicidality and one was currently receiving therapy.

Procedures

After initial contact with the investigators via email or telephone, participants were screened for eligibility using structured interviews. The eligibility screening was conducted in person by the first author, a licensed psychologist, or the second author, a doctoral student in a clinical health psychology program, acting under supervision of the first author. Participants were screened regarding whether they had experienced a sexual assault since the age of 14 years and whether they met criteria for current rape-related PTSD. In addition, participants were screened for current substance dependence and suicidality. To be eligible, participants had to report at least one experience of rape since the age of 14, as well as meet criteria for rape-related PTSD. Women who reported significant current suicidal ideation or substance dependence were excluded, as were those currently receiving psychotherapy. After completing the screening interview, eligible women completed a number of online self-report questionnaires regarding the characteristics of their worst experience of sexual assault, rape-related cognitions, depressive symptoms, rape-related fears, anxious symptoms, and their history of other traumas. After completion of the interview and questionnaires, participants were compensated for their time with a $50 gift certificate and were given information about how to access the program online as well as a user name and password to log in.

Participation in the study involved coming into the lab on a weekly to twice weekly basis to complete the S to T online program modules. At each visit, participants were interviewed by the first or second author regarding their impressions of the last program module they completed utilizing open-ended questions (e.g., what aspects of the module was most helpful, suggestions for improving the program module). Participants were then given access to the next module. Between in-person sessions, participants were encouraged to work on the program at home by logging on to the program website via the Internet using their personal username and password. Participants were provided with online individualized line-by-line feedback regarding their responses to interactive program exercises by the first author within 24 hours of completing an exercise. Participants completed the intervention over the course of 6 to 7 weeks.

Several steps were taken to ensure that contact with investigators did not result in the provision of in-person therapy. First, interviewers used a set of standard questions to assess participants’ impressions of the most recently completed program module. In addition, if a participant began discussing any concerns with their responses to the program or other stressors in her life, she was encouraged to utilize the program to work on this concern and receive online feedback. Finally, participants completed program modules alone in the laboratory and only questions regarding technical issues were addressed with participants while they completed program modules.

After completion or termination of the study, participants completed the PTSD interview (administered by the first or second author) in person or over the telephone and completed the online questionnaires. After completion of these measures, participants were again compensated with a $50 gift certificate. All study procedures were approved by the university institutional review board. In addition, women were given a written list of area crisis resources prior to initiating the program and the online program itself contained information about these resources on the main page.

Interview Measures

Sexual Assault Screening Items

Three behaviorally specific items from the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss et al., 2007) were administered in the screening interview to assess experiences of rape or sexual assault since the age of 14. Items assessed unwanted sexual experiences (oral, anal, vaginal intercourse, or object penetration) perpetrated through the use or threat of force, or that occurred when the individual was incapacitated or intoxicated as a result of substance use.

PTSD Diagnostic Status

The PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview (Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbamun, 1993) was administered to evaluate current PTSD diagnostic status. The PSS-I is a semistructured interview designed to reflect the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD. For each item, individuals rated the frequency of PTSD symptoms in the preceding month on a 4-point Likert scale anchored by 0 (not at all) and 3 (5 or more times per week/very much). This measure demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in a sample of rape victims and was found to have a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 96% for a diagnosis of PTSD when compared with another structured clinical interview (Foa et al., 1993).

Substance Dependence

The Substance Use Disorders Module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P SUD) was administered to evaluate current substance dependence (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). The SCID-I SUD is a semistructured interview designed to assess whether individuals meet DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse or dependence. The SCID-I SUD has been shown to have excellent interrater reliability, κs = 0.82 − 1.0, as well as good test-retest reliability, κs =0.76 − 0.77 (Martin, Pollock, Bukstein, & Lynch, 2000; Zanarini et al., 2000).

Suicidality

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS) was administered in an interview format to assess current suicidality (Beck & Steer, 1993). The BSS is a 21-item measure of current suicidal attitudes, behaviors, and plans. Initially, five screening items are administered. If an individual endorses any of these items, the full measure is administered (Beck & Steer). The BSS has been shown to have good psychometric properties and to prospectively predict suicide risk (Brown, Beck, Steer, & Grisham, 2000).

Self-Report Measures

Assault Characteristics

Participants completed an online questionnaire regarding the circumstances of their worst sexual assault experience (Littleton, Axsom, Radecki Breitkopf, & Berenson, 2006). Participants completed items regarding their relationship with the assailant (stranger/just met, acquaintance/friend, steady date/romantic partner) and age at the assault. They also recorded the types of force the assailant used: nonverbal threats/intimidation, verbal threats, moderate physical force (using his superior body weight, twisting your arm or holding you down), and severe physical force (hitting or slapping you, choking or beating you, showing or using a weapon). Similarly, they recorded the types of resistance they utilized: nonverbal resistance (turned cold, cried), verbal resistance (reasoned or pleaded with him, told him “no,” screamed for help), and physical resistance (ran away, physically struggled). In addition, participants estimated the number of standard drinks consumed prior to the assault, coded as binge drinking or non–binge drinking (four standard drinks or more; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, 2006). Finally, participants indicated if multiple assailants were involved.

Traumatic Event Exposure

The Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (SLESQ) was administered to assess exposure to other interpersonal traumas (Goodman, Corcoran, Turner, Yuan, & Green, 1998). The SLESQ is a 13-item measure that assesses lifetime exposure to traumatic events. Test-retest reliability for the SLESQ has been shown to be good (Green et al., 2000).

Depressive Symptomatology

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was administered to assess depressive symptoms. For each of the 20 items, individuals indicated how often they have felt that way in the past week on a 4-point Likert scale bounded by 0 (rarely or none of the time/less than one day) and 3 (most or all of the time/5–7 days), with scores of 23 or above indicating probable depression (Myers & Weissman, 1980). Multiple studies support the measure's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (Radloff; Weissman, Sholomskas, Pottenger, Prusoff, & Locke, 1977).

Anxious Symptomatology

The 35-item Four Dimensional Anxiety Scale (FDAS) was administered to assess the emotional, physiological, cognitive, and behavioral components of anxiety (Bystritsky, Linn, & Ware, 1990). Individuals rated the extent to which they were bothered by each anxiety symptom in the past week on a 5-point Likert scale bounded by 0 (not at all) and 5 (extremely). Prior research supports the measure's internal consistency and convergent validity (Bystritsky et al., 1990; Stoessel, Bystritsky, & Pasnau, 1995).

Rape-Related Fears

Rape-related fears were assessed with the vulnerability fears (e.g., being alone, parking lots, sudden noises) and sexual fears (e.g., sexual intercourse, nude men, a man's penis) subscales of the Veronen-Kilpatrick Modified Fear Survey (Resick, Veronen, Kilpatrick, Calhoun, & Atkeson, 1986). Individuals rated the extent to which they found each item fear-provoking or disturbing on a 5-point Likert scale bounded by 1 (not at all) and 5 (very much). In a sample of college rape victims, the internal consistency of both of these subscales was acceptable, α = .89 and α = .78, respectively (Littleton, 2007). Supporting the validity of these subscales, scores on both were found to differentiate rape victims from nonvictims (Resick et al., 1986).

Trauma-Related Schemas

The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI; Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin, & Orsillo, 1999) was administered to assess trauma-related thoughts and beliefs. This 33-item measure assesses three types of negative posttraumatic cognitions: negative cognitions about the world (“The world is a dangerous place”), negative cognitions about the self (“I am inadequate”), and self-blame (“The event happened to me because of the sort of person that I am”). Individuals indicated how much they agreed with each statement with regard to their experience of unwanted sex on a 7-point Likert scale bounded by 1 (totally disagree) and 7 (totally agree). Prior research supports the measure's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (Foa et al., 1999).

Analysis Plan

Changes in participants’ scores on study measures were assessed using the reliable change index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991). The RCI is a measure of clinically significant improvement following treatment. To calculate the RCI, a participants’ pretest score is first subtracted from their posttest score. This value is then divided by the standard error of the difference. The standard error of the difference is derived from the standard error of the measurement utilizing the standard deviation of participants’ pretest scores as well as the measure's reliability. The resulting RCI value is a Z score, and thus scores above 1.96 represent significant change (Jacobson & Truax). Prior research supports that the RCI is a more conservative estimate of clinically significant change than other extant measures (Hays, Brodsky, Johnston, Spritzer, & Hui, 2005).

Description of the Intervention

The S to T program consists of nine program modules (see Appendix A). The first modules focus on psychoeducation and instruction in relaxation, grounding, and utilization of adaptive coping. These modules are included to reduce maladaptive coping and increase adaptive coping. This seems particularly important given that the program does not include in-person therapy support. The next modules introduce the cognitive model and cognitive restructuring. The final modules focus on using cognitive techniques to address specific concerns regarded as highly relevant to the experiences of rape victims (e.g., self-blame, safety concerns).

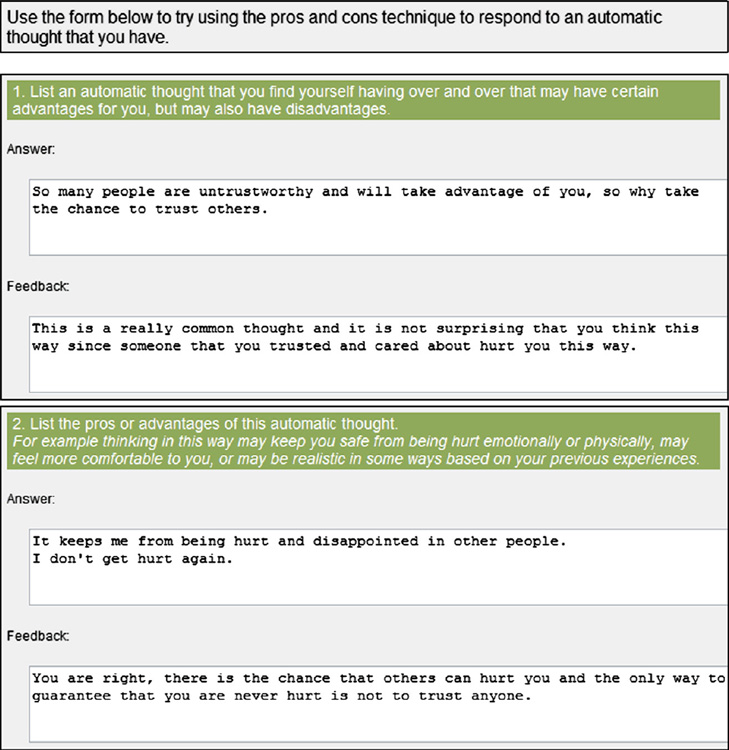

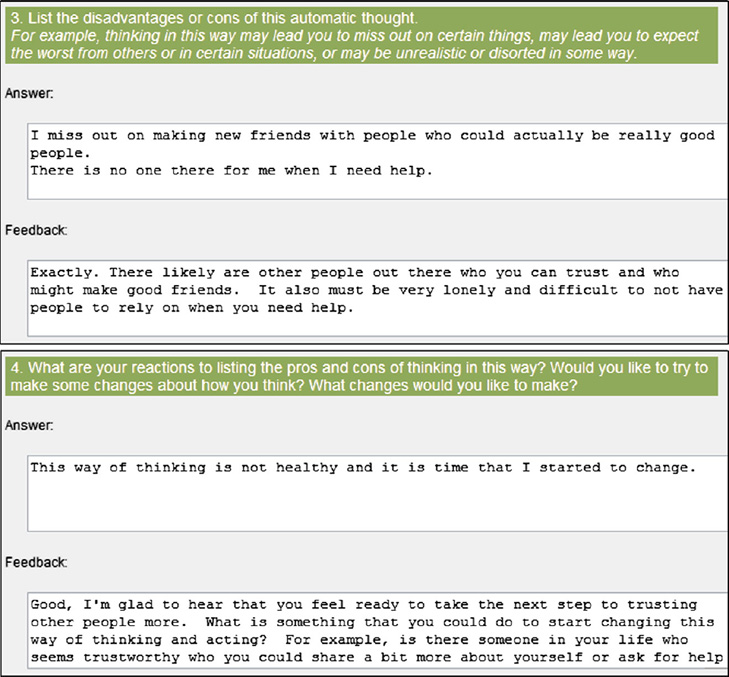

Women complete one module at a time, and are given access to each subsequent module by their therapist. Each module contains several components: a video clip discussing the topic covered in the module, a written description of the skills or techniques being introduced or utilized in the module, and written examples of women modeling the skills and techniques. The final program component is the interactive exercises. These interactive exercises either are designed to help women think about the extent to which the particular issue raised in the module (e.g., the extent to which they blame themselves for the sexual assault) is a concern for them or are designed to enable women to practice a described skill or technique and receive feedback on their practice. The interactive exercises are designed in a question-and-answer format (e.g., “What were your automatic thoughts in this situation?” “How do you know if you can trust someone?”). The therapist can then provide feedback to each answer provided in the interactive exercise. This feedback could take the form of encouraging and praising the client for their effort, expressing empathy, or providing assistance in challenging automatic thoughts, such as through use of Socratic questioning. Thus, the interactive exercises serve to both increase efficacy to use the skills and to assist individuals who are having any difficulty with the interactive exercises. Of note, this feedback is provided within the program, thus circumventing security issues with using email, which has been used in prior online interventions (Knaevelsrud & Maercker, 2007; Lange et al., 2000; Lange et al., 2003).

Finally, the interactive exercises provide valuable information to the therapist regarding the extent to which the issue in the module is a concern for the client. This information aids the clinician in determining how much time clients should spend on that particular module. For example, if a client indicated in the self-blame interactive exercise that she did not believe she was at all to blame for her experience with unwanted sex, then her therapist could immediately give her access to the next module as opposed to having her complete additional module content. A sample (fictional) interactive exercise from the program is provided in Appendix B.

Results

Trauma History

Participants reported that they were between 16 and 18 years old when their sexual assault occurred. One had just met her assailant, two reported he was an acquaintance, and two were romantically involved with him. Four had engaged in binge drinking prior to the assault. All reported that the assailant used moderate physical force (e.g., holding her down, using his body weight) and verbal threats. All reported using both verbal and physical resistance (e.g., saying no, physically struggling). Two participants’ assaults involved multiple assailants. Four also reported significant histories of other types of interpersonal trauma: three were sexually abused (involving fondling, attempted intercourse, and/or intercourse), two were physically abused as a child, one witnessed her mother being physically abused by a partner, and one had been in a physically violent romantic relationship. Participant characteristics, participants’ assault characteristics, and their prior trauma history are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Assault Characteristics and Prior Interpersonal Trauma History

| ID | Age | Age at assault |

Relationship with assailant |

Force by assailant | Resistance by victim | Binge drinking by victim |

Multiple assailants |

Prior interpersonal trauma history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 18 | Friend | Intimidation, Moderate force | Verbal, Physical | Yes | No | Sexually abused, Witnessed domestic violence |

| 2 | 19 | 17 | Romantic partner | Intimidation, Verbal threats, Moderate force | Nonverbal, Verbal, Physical | No | Yes | Sexually abused, Physically abused by romantic partner |

| 3 | 20 | 18 | Just met | Moderate force | Nonverbal, Verbal, Physical | Yes | No | None |

| 4 | 18 | 16 | Casual date | Moderate force | Verbal, Physical | Yes | No | Sexually abused, Physically abused as a child |

| 5 | 18 | 16 | Acquaintance | Intimidation, Moderate force | Nonverbal, Verbal, Physical | Yes | Yes | Physically abused as a child |

Scores on Symptom Measures

All participants met diagnostic criteria for rape-related PTSD prior to initiating the program. Their mean score on the PSS was well above the clinical cutoff of 14, M=25.6, SD=3.5 (Coffey, Gudmundsdottir, Beck, Palyo, & Miller, 2006). Their mean score was also similar to other treatment-seeking samples of rape victims (Ms =26 – 31; Foa et al., 2005; Foa, Riggs, Massie, & Yarczower, 1995; Ironson, Freund, Strauss, & Williams, 2002; Rothbaum, Astin, & Marsteller, 2005; Van Minnen & Foa, 2006; Zoellner, Feeny, Fitzgibbons, & Foa, 1999). On the self-report measures, participants reported elevated depressive and anxious symptoms, high levels of vulnerability fears, as well as elevated adherence to trauma-related schemas. Two participants also reported elevated sexual fears. Their scores on these measures are summarized in Table 2. It should be noted that due to a technical error, a pretreatment score on the anxiety measure was not available for Participant 2.

Table 2.

Pre- and Posttest Scores of Participants on Study Measures and Reliable Change Index Scores from Pre- to Posttesting

| ID | PTSD | CES-D | FDAS | Vulnerability fears |

Sexual fears | World cognitions | Self cognitions | Self-blame |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre 20 | Pre 30 | Pre 122 | Pre 57 | Pre 8 | Pre 29 | Pre 43 | Pre 17 |

| Post 4 | Post 36 | Post 48 | Post 23 | Post 5 | Post 31 | Post 27 | Post 11 | |

| RCI 8.3* | RCI −1.7 | RCI 10.2* | RCI 10.5* | RCI 0.6 | RCI −0.7 | RCI 3.3* | RCI 2.2* | |

| 2 | Pre 29 | Pre 33 | Pre —— | Pre 55 | Pre 7 | Pre 31 | Pre 84 | Pre 27 |

| Post 5 | Post 16 | Post 62 | Post 41 | Post 5 | Post 18 | Post 50 | Post 11 | |

| RCI 12.5* | RCI 4.8* | RCI —— | RCI 4.3* | RCI 0.4 | RCI 4.3* | RCI 7.1* | RCI 5.9* | |

| 3 | Pre 26 | Pre 17 | Pre 81 | Pre 44 | Pre 21 | Pre 31 | Pre 63 | Pre 22 |

| Post 9 | Post 26 | Post 95 | Post 30 | Post 12 | Post 35 | Post 57 | Post 25 | |

| RCI 8.8* | RCI − 2.6 | RCI −1.9 | RCI 4.3* | RCI 1.7 | RCI −1.3 | RCI 1.3 | RCI −1.1 | |

| 4 | Pre 25 | Pre 20 | Pre 81 | Pre 41 | Pre 22 | Pre 26 | Pre 36 | Pre 14 |

| Post 2 | Post 6 | Post 38 | Post 21 | Post 6 | Post 15 | Post 22 | Post 8 | |

| RCI 12.0* | RCI 4.0* | RCI 5.9* | RCI 6.2* | RCI 3.1* | RCI 3.7* | RCI 2.9* | RCI 2.2* | |

| 5 | Pre 28 | Pre 29 | Pre 95 | Pre 51 | Pre 7 | Pre 42 | Pre 69 | Pre 23 |

| Post 27 | Post 31 | Post 89 | Post 35 | Post 5 | Post 34 | Post 64 | Post 20 | |

| RCI 0.5 | RCI −0.6 | RCI 0.8 | RCI 4.9* | RCI 0.4 | RCI 2.7* | RCI 1.0 | RCI 1.1 |

Note. CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; FDAS=Four Dimensional Anxiety Scale.

p<.05.

Four participants completed the entire program and one completed through module seven (Participant 2) when posttest data were collected. At posttesting, four of the five participants no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Participants 1 through 4). The RCI for these four participants on the PTSD measure was significant as well. Looking at participants’ scores on the self-report measures, Participant 1 reported significant reductions in anxiety, vulnerability fears, negative self-cognitions, and self-blame. Participant 2 reported significant reductions in depression, vulnerability fears, and all three types of negative trauma-related cognitions. Participant 3 reported significant reductions in vulnerability fears. Participant 4 reported significant reductions on all the self-report measures. Finally, Participant 5 reported significant reductions in vulnerability fears and negative world cognitions. Participants’ pre- and posttest scores and RCI scores on each measure are summarized in Table 2.

Impressions of the Intervention

Interviews with participants regarding their overall impressions of the program supported that all found the intervention to be helpful and relevant to their personal experiences. With regard to specific aspects of the program content, all reported positive impressions of the video messages (although two reported difficulty with viewing the videos at some point in the program due to a software compatibility issue) and all reported positive impressions of the examples of women using the skills presented. Two participants reported difficulties with understanding the cognitive restructuring exercises at some point (including the participant who did not experience significant reductions in PTSD symptomatology). Because participants completed the program over a short time period, they had not always reviewed the feedback they received in the most recent module before they were interviewed about that particular module; however, when participants had reviewed this feedback, they uniformly described it as helpful. Similarly, in their interviews about the program overall, all participants reported positive impressions of the online feedback. Finally, three participants reported some difficulty with navigating through the overall program layout, including determining how many interactive exercises to complete in a particular module.

Discussion

Efficacy of the Intervention

Results of this pilot study supported that the S to T program is a potentially efficacious intervention for women with rape-related PTSD. Four women experienced clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptomatology, no longer meeting criteria for PTSD at posttesting. Participants’ responses to the self-report measures also supported the potential efficacy of the program, with all but one participant experiencing significant reductions in at least one of the types of negative trauma-related cognitions (negative world cognitions, negative self cognitions, and self-blame) and all reporting clinically significant reduction in their vulnerability fears. Some participants also experienced reductions in general distress with one participant reporting a significant reduction in general anxiety symptoms, one reporting a significant reduction in depression symptoms, and one reporting significant reductions in both types of symptoms. Finally, one of the two participants with sexual fears reported a significant reduction in these fears. Participants reported finding the program to be relevant to their personal experience and viewed participating in the program as helpful. No participants reported any adverse reactions to any elements of the program. It is also important to note that the program was efficacious among a group of women experiencing significant levels of rape-related distress. Indeed, unlike some previous online programs for trauma, all reported clinically significant distress, meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD at pretesting.

Limitations and Future Directions

Given the promising nature of the current results, future evaluations of the S to T program appear warranted. However, it is also important to note the limitations of the current evaluation. First, while women in the current study were not given face-to-face therapy, they completed the bulk of the program in a laboratory setting with a study therapist available to address any technical problems that occurred. Future investigations should therefore evaluate the efficacy of the program among women completing the program at home to identify potential barriers to home completion (e.g., lack of privacy, not being able to schedule blocks of time to work on the program) as well as to examine how long it takes women to complete the program in a more naturalistic setting. Future evaluations should also compare the efficacy of the program to another online program (e.g., a psychoeducational website) to examine the extent to which the presumed “active” elements of the program (e.g., instruction in cognitive restructuring, therapist interaction) result in improvements in symptoms above that of providing psychoeducation about trauma and PTSD. In addition, given that two of the participants did report some difficulty with completing the cognitive restructuring exercises, ways to revise this content to make it easier for participants to understand seems warranted, such as including more discussion of what types of thoughts are good candidates to evaluate using cognitive restructuring (e.g., thoughts that fit one of the types of common cognitive distortions such as labeling, fortune telling, black-and-white thinking) and what types of thoughts are not (e.g., facts about a situation or someone's behavior). Finally, some revisions to the program layout are clearly warranted to reduce confusion regarding which aspects of the program to complete, and inclusion of instructions for preventing compatibility issues is also necessary given that two participants had difficulty viewing the videos initially.1

It is also important to note that while the current program leveraged a number of advantages of online interventions, a number of potential advantages were not utilized. In particular, it was noted that there was not a mechanism in the program to respond to participants quickly when they had difficulties with the program. It also was unclear at times the exact nature of the difficulty a participant was experiencing with the program without speaking to her face-to-face. Thus, future evaluations of this program should integrate ways for participants to interact with their therapist if they have difficulties, such as setting aside times for participants to text or video chat with their therapist. In addition, it was sometimes difficult to fully convey empathy or to respond to highly distorted cognitions expressed by participants in the written interactive exercises. For example, one participant reported a strong belief that if she told others about her assault that they would judge her, and completing the challenging questions exercise did not result in any change in her belief that this would occur. Future evaluations may therefore wish to combine the written feedback with audio or video messages to participants regarding their responses to the interactive exercises.

In addition, although the current intervention had a clear positive impact on women's trauma-related symptoms, most participants did not report significant improvements in more general symptoms of distress (i.e., general anxiety and depression). This may reflect the fact that treatment was completed in only 6 or 7 weeks and women were assessed 7 to 8 weeks after beginning the program. It is possible that participants may have experienced greater improvements in general distress if they had been followed for a longer period of time or had more time to complete the program. Indeed, given that empirical research supports that anxiety and depression are frequently consequences of PTSD symptomatology (Wittmann, Moergeli, Martin-Soelch, Znoj, & Schnyder, 2008), it may be possible that an individual's PTSD symptoms need to remit before he or she experiences improvement in general symptoms of distress. Therefore, it is important for future evaluations of this program to follow-up participants for a longer time period to assess the extent to which the intervention has a positive impact on symptoms of general distress.

Finally, it is important to note that the current study involved a sample of college women. College women were chosen because they are in many ways an ideal population for this type of intervention. First, college women are frequent users of the Internet, reporting both frequent general use and use to obtain health information (Escoffery et al., 2005). College women are also unfortunately frequently victims of rape and often report PTSD in connection to this experience (Littleton & Henderson, 2009). Indeed, the level of distress reported in the current sample supports that college women can experience significant psychological distress in connection to this experience. However, it is clear that future evaluations should examine the program's efficacy in other populations as well, and should adapt program content as necessary (e.g., including less written content for populations with lower literacy rates).

Implications for Clinicians

The current study supports that the S to T program is a potentially useful tool in helping victims of sexual assault. There are several ways in which a program such as the current one could be utilized in clinical practice. First, the program could be administered completely online. This could be particularly helpful for clinicians who practice in remote areas or who serve large geographic areas where provision of face-to-face services may not be practical. Similarly, the program could be helpful in enabling individuals who live in areas where there are not clinicians with expertise in working with trauma victims to receive services from a clinician with this expertise. The S to T program could also be a useful supplemental tool for in-person therapy. For example, rather than having clients read a chapter or complete a worksheet between sessions, clients could instead complete online program modules. This could be a superior option in many cases as clients may find the online materials to be more engaging than a book or other reading. Importantly, this would also enable the therapist to check on between-session progress as well as provide support and feedback between sessions, which would also result in more efficient use of in-person session time. Finally, a program such as the S to T could be useful for working with clients who are unable to attend weekly in-person sessions either due to transportation or financial issues or for clinicians that work with clients in health settings (e.g., primary care psychologists) and thus may only see clients face-to-face when they attend their healthcare visits.

Regardless of the format in which an online program such as this is provided, clinicians utilizing this type of treatment may face a number of unique challenges. First, clinicians will need to identify how they could best incorporate a program such as this into their existing practice based on such factors as their location, clientele, and whether they want to supplement online treatment with in-person sessions or conduct treatment completely online. Even though online treatment may be more efficient with regard to the amount of clinician time necessary, clinicians will need to develop a system for billing for their time, particularly given that they likely would not receive insurance reimbursement. Some possibilities could be charging a flat fee to the client for using the program or having the client prepay for a certain number of online therapist hours. In addition, clinicians need to discuss with clients the time frame in which they will receive feedback from their therapist, particularly as clients may have the expectation that because the treatment is online,a therapist is available to them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It is also apparent that clinicians need to have a plan in place for handling crisis situations prior to initiating online treatment and need to convey this plan to their clients. Some examples would be establishing a relationship with a clinician in the client's local area who could provide crisis sessions if necessary, discussing with the client that crisis services cannot be provided and a specific plan if she experiences a crisis, and locating crisis service providers in the client's area. Finally, given the possibility that clients may experience technical difficulties or difficulties with completing aspects of an online program, clinicians need to develop a plan for how clients can contact their online therapists if they experience a problem. One possibility could be allowing clients to sign up for office hours with their clinician using technology such as text chatting, voice over Internet, web cam, or telephone. Another option would be having a staff member available to address technical or program problems. Overall, however, it is clear that online treatments represent a potential avenue to provide effective services to clients in need and can have a number of potential advantages, particularly if clinicians are mindful of the unique challenges presented by these treatments.

Appendix A

| Topic | Module components |

|---|---|

| Module 1: The impact of unwanted sex | -Video introduction and welcome to the program |

| -Video discussing the symptoms of PTSD | |

| -Written welcome and overview of the program | |

| -Written narrative of a woman describing the impact of her experience of unwanted sex | |

| -Interactive exercise to assist participants in identifying how they have been affected by their experiences of unwanted sex | |

| Module 2: Introduction to relaxation | -Written descriptions of the stress response and relaxation response |

| -Video discussion of tips for improving the effectiveness of relaxation practice | |

| -Audio recordings of relaxation exercises: diaphragmatic breathing, autogenic training, imagery | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to discuss their experience with relaxation practice | |

| Module 3: Introduction to increasing adaptive coping | -Written introduction to the coping module |

| -Video discussion of several types of adaptive and maladaptive coping | |

| -Descriptions of specific forms of adaptive coping with written narratives of women replacing previous maladaptive coping with these adaptive methods | |

| -Written description of grounding as a way to cope with dissociation or strong emotions | |

| -Video demonstration of several grounding exercises | |

| -Interactive exercise consisting of a checklist for participants to identify their current adaptive coping | |

| -Interactive exercises for participants to record their efforts to replace maladaptive coping with new adaptive coping strategies | |

| Module 4: Introduction to automatic thoughts | -Video discussion describing automatic thoughts and their impact on mood and behavior |

| -Written description of several common types of automatic thoughts | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to begin recording and becoming more aware of their automatic thoughts | |

| Module 5: Introduction to the challenging questions technique | -Video introduction to the challenging questions technique |

| -Written narratives of three women using the challenging questions technique in response to upsetting events | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to begin using the challenging questions technique to respond to automatic thoughts | |

| Module 6: Coping with feelings of stigma, low self-worth, and shame | -Video discussion of how unwanted sex can lead to low self-worth and shame as well as stigma concerns |

| -Written narratives of women using the challenging questions technique to respond to thoughts related to low worth, shame, or stigma concerns | |

| -Introduction to the pros and cons technique and written narrative of a woman using the technique | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to explore their stigma concerns and perception of their own worth | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the challenging questions technique in response to automatic thoughts related to stigma, low self-worth, or shame | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the pros and cons technique for thoughts related to stigma, low self-worth, or shame | |

| Module 7: Coping with feelings of self-blame | -Video discussion of common self-blaming thoughts after unwanted sex |

| -Written narratives of women using the challenging questions technique to respond to self-blaming thoughts | |

| -Introduction to the re-attribution technique and written narrative of a woman using the re-attribution technique to respond to self-blame | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to explore their self-blaming thoughts | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the challenging questions technique in response to self-blame | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the re-attribution technique to respond to self-blame | |

| Module 8: Coping with concerns about trust and intimacy | -Video discussion of common trust and intimacy concerns after unwanted sex |

| -Written narratives of women using the challenging questions technique to respond to trust and intimacy concerns | |

| -Introduction to graded exposure and written narrative of a woman using graded exposure to respond to an intimacy concern | |

| -Introduction to using behavioral experiments and written narrative of a woman using a behavioral experiment to respond to a trust concern | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to explore their trust or intimacy concerns | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the challenging questions technique in response to trust or intimacy concerns | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to record their use of graded exposure in connection to a trust or intimacy concern | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to record the results of a behavioral experiment related to a trust or intimacy concern | |

| Module 9: Safety concerns | -Video discussion of common safety concerns after unwanted sex |

| -Written narratives of women using the challenging questions technique to respond to safety concerns | |

| -A written narrative of a woman using graded exposure to respond to safety concerns | |

| -A written narrative of a woman using the pros and cons technique to respond to safety concerns | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to explore their safety concerns | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the challenging questions technique in response to safety concerns | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to record their use of graded exposure | |

| -Interactive exercise for participants to use the pros and cons technique in response to a safety concern |

Appendix B

Footnotes

A revised version of the S to T program is being developed by the authors incorporating all of these changes

Contributor Information

Heather Littleton, East Carolina University.

Katherine Buck, East Carolina University.

Lindsey Rosman, East Carolina University.

Amie Grills-Taquechel, University of Houston.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation Manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DK, Gulledge KM, Lee CM, Replogle W. Prevalence of sexual assault among women patients seen in family practice clinics. The Family Practice Research Journal. 1994;14:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux E, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Best CL, Saunders B. Criminal victimization, posttraumatic stress disorder, and comorbid psychopathology among a community sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:665–678. doi: 10.1023/A:1024437215004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G, Beck A, Steer R, Grisham J. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20 year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystritsky A, Linn LS, Ware JE. Development of a multidimensional scale of anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1990;4:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chard KM. An evaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:965–971. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier S, Martin SL, Poole C. Sexual assault among North Carolina women: Prevalence and health risk factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56:265–271. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.4.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum GA, Calhoun KS, Kimerling R. Associations among symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported health in sexually assaulted women. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188:671–678. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudmundsdottir B, Beck JG, Palyo SA, Miller L. Screening for PTSD in motor vehicle accident survivors using the PSS-SR and IES. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:119–128. doi: 10.1002/jts.20106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffery C, Miner KR, Adame DD, Butler S, McCormick L, Mendell E. Internet use for health information among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2005;53:183–188. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.4.183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. Patient Edition New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark DM, Tolin DF, Orsillo SM. The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SAM, Riggs DS, Feeny NC. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbamun BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Massie ED, Yarczower M. The impact of fear activationand anger on the efficacy of exposure treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:487–499. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, Murdock TB. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Anderson BP. Psychiatric disorders in rape victims: Past history and current symptomatology. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1987;28:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman L, Corcoran C, Turner K, Yuan N, Green B. Assessing traumatic event exposure: General issues and preliminary findings for the Stressful Life Events Questionnaire. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:521–542. doi: 10.1023/A:1024456713321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Goodman L, Krupnick J, Cocoran C, Petty M, Stockton P, et al. Outcomes of single versus multiple trauma exposure in a screening sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:271–286. doi: 10.1023/A:1007758711939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Brodsky R, Johnston MF, Spritzer KL, Hui K-K. Evaluating the statistical significance of health-related quality-of-life change in individual patients. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2005;28:160–171. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Clum GA. An internet-based self-change program for traumatic event related fear, distress, and maladaptive coping. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:631–636. doi: 10.1002/jts.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Freund B, Strauss JL, Williams J. Comparison of two treatments for traumatic stress: A community-based study of EMDR and prolonged exposure. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:113–128. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AS, Jackson J, Kully C, Badger K, Halvorsen J. Calling it rape: Differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders B, Best CL. Rape, other violence against women, and posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Dohrenwend BP, editor. Adversity, stress, and psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based treatment for PTSD reduces distress and facilitates the development of a strong therapeutic alliance: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:13–22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Long-term effects of an Internet-based treatment for posttraumatic stress. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2010;39:72–77. doi: 10.1080/16506070902999935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, et al. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Hill EE, Owens JA. Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD: Preliminary findings. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:81–91. doi: 10.1023/A:1022019629803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, Rietdijk D, Hudcovicova M, van de Ven JP, Schrieken B, Emmelkamp PMG. Interapy: A controlled randomized trial of the standardized treatment of posttraumatic stress through the Internet. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:901–909. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, Schrieken B, van de Ven JP, Bredeweg B, Emmelkamp PMG, van der Kolk J, et al. “Interapy”: The effects of a short protocolled treatment of posttraumatic stress and pathological grief through the Internet. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2000;28:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL. An evaluation of the coping patterns of rape victims: Integration with a schema-based information processing model. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:789–801. doi: 10.1177/1077801207304825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL. The impact of social support and negative disclosure reactions on sexual assault victims: A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2010;11:210–227. doi: 10.1080/15299730903502946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Axsom D, Radecki Breitkopf C, Berenson AB. Rape acknowledgment and post assault experiences: How acknowledgment status relates to disclosure, coping, worldview, and reactions received from others. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:765–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Grills-Taquechel AE, Axsom D. Impaired and incapacitated rape victims: Assault characteristics and post-assault experiences. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:439–457. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Henderson CE. If she is not a victim, does that mean she was not traumatized? Evaluation of predictors of PTSD symptomatology among college rape victims. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:148–167. doi: 10.1177/1077801208329386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Engel CC, Bryant RA, Papa A. A randomized, controlled proof-of-concept trial of an internet-based, therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1676–1683. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Pollock NK, Bukstein OG, Lynch KG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID alcohol and substance use disorders section among adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JK, Weissman MM. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:1081–1084. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking: Why do adolescents drink, what are the risks, and how can underage drinking be prevented? Alcohol Alert. 2006 Jan;67 Retrieved April 1, 2007, from. www.niaaa.nih.gov/Publications/AlcoholAlerts/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Galvoski TA, Uhlmansiek MO, Scher CD, Clum GA, Young-Xu Y. A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:243–258. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin M, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:748–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Veronen LJ, Kilpatrick DG, Calhoun KS, Atkeson BM. Assessment of fear reactions in sexual assault victims: A factor analytic study of the Veronen-Kilpatrick Modified Fear Survey. Behavior Assessment. 1986;8:271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Astin MC, Marsteller F. Prolonged exposure versus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:607–616. doi: 10.1002/jts.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoessel PW, Bystritsky A, Pasnau RO. Screening for anxiety disorders in the primary care setting. Family Practice. 1995;12:448–451. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women's experiences of sexual aggression using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Van Minnen A, Foa EB. The effect of imaginal exposure length on outcome of treatment for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:427–438. doi: 10.1002/jts.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1977;106:203–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann L, Moergeli H, Martin-Soelch C, Znoj H, Schnyder U. Comorbidity in posttraumatic stress disorder: A structural modelling approach. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of Axis I and II diagnosis. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Fitzgibbons LA, Foa EB. Response of African American and Caucasian women to cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. Behavior Therapy. 1999;30:581–595. [Google Scholar]