Abstract

Amyloid imaging may revolutionize Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research and clinical practice but is critically limited by an inadequate correlation between cerebral cortex amyloid plaques and dementia. Also, amyloid imaging does not indicate the extent of neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) spread throughout the brain. Currently, the presence of dementia as well as a minimal brain load of both plaques and NFTs is required for the diagnosis of AD. Autopsy studies suggest that striatal amyloid plaques may be mainly restricted to subjects in higher Braak NFT stages that meet clinicopathological diagnostic criteria for AD. Striatal plaques, which are readily identified by amyloid imaging, might therefore be used to predict the presence of a higher Braak NFT stage and clinicopathological AD in living subjects. This study determined the sensitivity and specificity of striatal plaques for predicting a higher Braak NFT stage and clinicopathological AD in a postmortem series of 211 elderly subjects. Subjects included 87 clinicopathologically classified as non-demented elderly controls and 124 with AD. A higher striatal plaque density score (moderate or frequent) had 95.8% sensitivity, 75.7% specificity for Braak NFT stage V or VI and 85.6% sensitivity, 86.2% specificity for the presence of dementia and clinicopathological AD (National Institute on Aging – Reagan Institute “intermediate” or “high”). Amyloid imaging of the striatum may be useful as a predictor, in living subjects, of Braak NFT stage and the presence or absence of dementia and clinicopathological AD. Validation of this hypothesis will require autopsy studies of subjects that had amyloid imaging during life.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid imaging, striatum, amyloid plaques, diagnosis, therapy, asymptomatic, preclinical, autopsy

Introduction

Amyloid imaging may revolutionize Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research and clinical practice but is critically limited by an inadequate correlation between cerebral cortex amyloid plaques and dementia. Recent amyloid imaging results [1–6] have confirmed longstanding neuropathological reports [7–19] that many non-demented elderly individuals have cortical amyloid plaques. Amyloid imaging does not indicate the extent of neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) spread throughout the brain and this is a major shortcoming as current diagnostic criteria require the presence of both dementia as well as a minimal brain load of both plaques and NFTs to make the clinicopathological diagnosis of AD [20].

Autopsy studies as well as amyloid imaging suggest that the presence of amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex alone is not an accurate predictor of clinicopathological AD but that the additional presence of amyloid plaques in the caudate nucleus and/or putamen (together termed the striatum) might make this distinction possible. Striatal amyloid plaques were first comprehensively reported by Rudelli, Ambler and Wisniewski in 1984 [21] and there was renewed interest after the development of Aβ immunohistochemistry [22]. While some investigators reported that striatal plaques were only of the diffuse type [23], several studies clearly showed that a wide range of plaque morphologies are present, including diffuse, neuritic and cored types [21–25]. Biochemical studies have suggested that striatal plaques are composed predominantly or entirely of Aβ 1–42 and 1–43, with some common posttranslational modifications [26, 27]. Some studies indicated that striatal plaques are largely restricted to individuals that had clinically-documented dementia [28, 29], although others have found them in small numbers of non-demented subjects [30]. Striatal plaques have also been reported to correlate with the presence of dementia in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies [31–33]. Additionally, striatal plaques have been reported to correlate with neuropsychological measures [30] and to predominantly occur at later histopathological stages of AD, corresponding to Braak neurofibrillary tangle stages V and VI [28].

These studies indicate that striatal amyloid plaques, which are readily identified by amyloid imaging, might therefore be used to predict the presence of clinicopathological AD in living subjects. Imaging reports of amyloid plaques have been primarily concerned with their presence in subjects with early-onset, autosomal dominant inheritance of AD, where they occur even at early-stage disease [34–37], but a few studies have documented striatal amyloid in late-onset sporadic AD [38,39] and one of these found the striatal amyloid signal in late-onset subjects to be equivalent to that in early-onset disease [40].

We therefore undertook to estimate, using a large subject number of autopsied and neuropathologically characterized subjects, the sensitivity and specificity of histopathologically-estimated striatal plaque load for predicting the presence of a higher Braak NFT stage and clinicopathological criteria for the diagnosis of AD.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

The study took place at Banner Sun Health Research Institute (BSHRI), located in the Sun Cities retirement communities of northwest metropolitan Phoenix, Arizona. The Institute is part of Banner Health, a regional not-for-profit health care provider centered in Arizona. Brain necropsies were performed on elderly subjects who had volunteered for the BSHRI Brain Donation Program, a longitudinal clinicopathological study of normal aging, dementia and parkinsonism [41]. The operations of the Brain Donation Program have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Banner Health.

Subjects were chosen by searching the Brain Donation Program database for non-demented elderly control and AD subjects that had had at least one standardized neurological assessment at our center during life. Subjects with conditions primarily considered to be movement disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration were excluded. Non-demented control subjects were defined as those that had not had a clinical diagnosis of dementia or parkinsonism. Subjects with AD were defined as those that had clinically-documented dementia and a neuropathological diagnosis of AD, meeting National Institute on Aging – Reagan Institute (NIA-Reagan) criteria of “intermediate” or “high” probability that dementia was due to AD; this included any combination of Braak NFT stages III-VI and moderate or frequent CERAD neuritic plaque density [20]. Subjects (see Table 1 for general subject characteristics) were clinically characterized by standardized periodic neurological and neuropsychological assessments, review of private medical records, self-report and telephone interviews with spouses and/or caregivers. As part of the Brain Donation Program’s standard protocol, two years of private medical records are obtained from the subjects’ private physicians, both at the time of enrollment and at the time of death. Subjects also fill out a medical history questionnaire in which they are asked to report any significant health conditions. Additionally, at the time of death, a telephone interview is conducted with the spouse and/or caregiver in which the presence of any major health conditions, symptoms or signs are again queried. All subjects in this study received at least one standardized assessment at BSHRI, which generally includes a physical examination, depression inventory, activities of daily living instrument, a neurological examination, a neuromotor assessment, a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Global Deterioration Scale (GDS), Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) and a neuropsychological test battery.

Table 1.

General characteristics of study subjects. Values for age and MMSE score are mean and standard deviation. For postmortem interval (PMI) the median is given. The groups differed as expected in their MMSE scores and in their percentages carrying the apoE-β4 allele. The groups did not significantly differ in PMI but the control group was significantly older than the AD group.

| Diagnosis (N) | Age | Gender | PMI (hrs) | ApoE-4 | MMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (87) | 87.0 (5.9) | 41F/46M | 3. 5 | 23.0% | 28.3 (1.8) |

| AD (124) | 81.4 (9.3) | 56 F/71M | 3.7 | 60.0% | 10.6 (16.5) |

Tissue processing and histological methods

The cerebrum was cut at the time of brain removal in the coronal plane into 1 cm thick slices and then divided into left and right halves. The brainstem was sliced axially while the cerebellum was sliced parasagitally. The slices from the right half were frozen between slabs of dry ice while the slices from the left half were fixed by immersion in buffered 4% formaldehyde for 48 hours at 4 degrees C. Following cryoprotection in ethylene glycol and glycerol, selected 3 × 4 cm cerebral, cerebellar and brainstem blocks were sectioned at 40 μm thickness on a sliding freezing microtome. Sections were stained with H & E, thioflavine S and enhanced silver methods for amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, using the Campbell-Switzer and Gallyas methods [42]. Thioflavine S is one of the methods recommended and validated for neuritic plaque density grading by the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) [43] while Braak neurofibrillary tangle staging was originally described using the Gallyas stain [44]. The validity and accuracy of this combination of stains for estimating the density of Aβ deposits has also been established in our own laboratory through strong correlations with autoradiographic binding of Florbetapir (R = 0.95), an amyloid imaging ligand, to postmortem human brain sections from AD subjects [45], and with biochemical measures (ELISA) of Aβ (R = 0.89) in human cerebral cortex extracts (unpublished data).

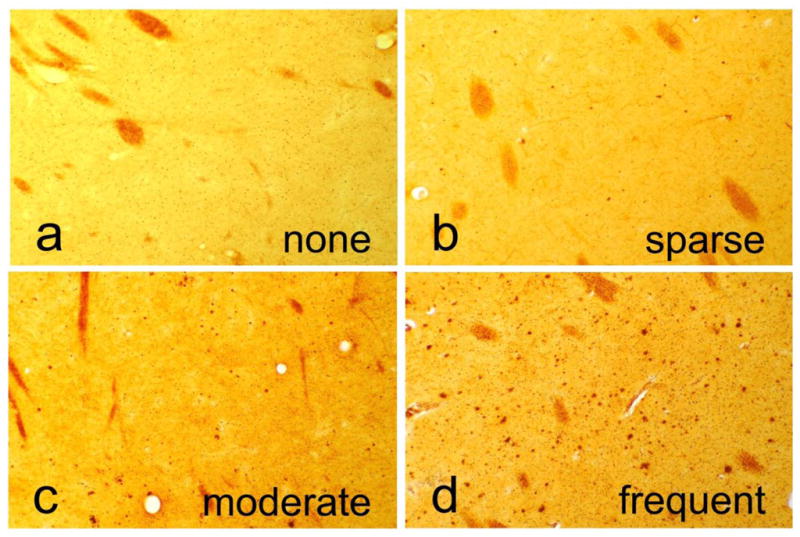

Histopathological scoring was performed blinded to clinical and neuropathological diagnosis. Amyloid plaque and NFT density were graded and staged at standard sites in frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortex as well as hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, based on the aggregate impression from the 40 μm sections stained with thioflavine S, Campbell-Switzer and Gallyas methods. The striatum was assessed within the putamen at the coronal level of the anterior thalamus. Scores for plaque density were derived by considering all types of plaques (cored, neuritic and diffuse) together, to obtain a “total” plaque score, while cored and neuritic plaques were also separately estimated. Plaque density scores were obtained by assigning values of none, sparse, moderate and frequent (see Figure 1), according to the published CERAD templates [43]. Conversion of the descriptive terms to numerical values resulted in scores of 0–3 for each area, with a maximum score of 15 for all five cortical areas combined (“total plaque score” and “total tangle score” in Table 2). Neurofibrillary tangle abundance and distribution was also graded in these thick sections, using the CERAD templates [43] for estimating tangle density, and the original Braak protocol [44] (“Braak Stage” in Table 2) for estimating topographical distribution. Diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia were adapted from those of Roman et al [46]. Diagnostic criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies were those of the third Dementia with Lewy Bodies Consortium [47]; the diagnosis was assigned when subjects met “intermediate” or “high” definitions. All subjects were genotyped for apolipoprotein E (ApoE) using a modification of a standard method [48].

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs depicting representative examples of striatum with no plaques and with sparse, moderate or frequent plaques. These are converted to numerical scores (0–3) for statistical purposes. The sections were stained with the Campbell-Switzer silver stain.

Table 2.

Striatal plaque scores compared to average cortical measures of Alzheimer’s disease-associated histopathology. All values are the median followed by mean and standard deviation. The AD group had significantly higher total striatal plaque score, striatal cored/neuritic plaque score, total cortical plaque score, total cortical tangle score, CERAD neuritic plaque density and Braak stage than the normal elderly control group.

| Diagnosis (N) | Striatal Total Plaque Score | Striatal Neuritic & Cored Plaque Score | Cortical Total Plaque Score | Cortical CERAD Neuritic Plaque Density | Cortical Total Tangle Score | Braak NFT Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (87) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4.2 | 3 |

| 0.5 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.3) | 5.7 (5.3) | 1.3 (1.1) | 4.5 (2.5) | 3.0 (0.9) | |

| AD (124) | 3 | 0.5 | 14.5 | 3 | 14.5 | 5 |

| 2.4 (0.9) | 0.75 (0.6) | 13.7 (2.0) | 2.9 (0.3) | 12.0 (3.8) | 5.0 (0.9) |

Statistical Analyses

The primary statistical analyses consisted of sensitivity and specificity calculations, performed using NCSS software. Group measures were compared using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test as appropriate. The significance level was considered to be 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

The basic characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. The 211 subjects were clinicopathologically classified as 87 non-demented elderly controls and 124 with AD. Of the AD cases, 18 also met clinicopathological criteria for vascular dementia (VaD), 18 met criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and 5 for hippocampal sclerosis (HS) while 2 met criteria for AD and DLB as well as VaD. Subjects with AD alone did not differ significantly in any demographic or AD-related neuropathological measures from those with AD/DLB, AD/VaD or AD/HS and therefore all were grouped together for further analysis. The AD and control groups differed as expected in their MMSE scores and in the percentages carrying the apolipoprotein E – E4 allele, with the AD group having significantly lower MMSE scores and significantly higher carrier rates than the control group. The groups did not significantly differ in terms of postmortem interval but the control group was significantly older (p < 0.001). Table 2 shows scores for AD histopathology. The groups differed as expected based on group definitions, with the AD group having significantly higher striatal plaque scores, total cortical plaque scores, total cortical tangle scores, cortical CERAD neuritic plaque density and Braak stage.

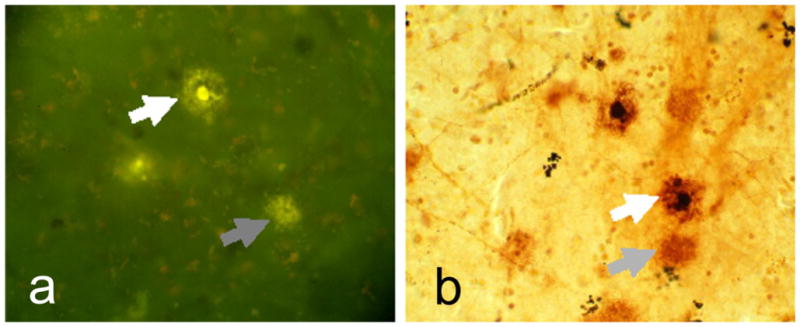

Striatal plaques (total, all types) were present in 118/124 AD subjects and in 27/87 elderly non-demented control subjects. Moderate or frequent striatal plaques (total, all types) occurred in 106/124 AD subjects but only 10/87 controls. Striatal plaques of the neuritic or cored type (Figure 2) were present in 100/124 AD subjects and in 17/87 control subjects. Total striatal plaque density scores correlated significantly with total cortical plaque score, total cortical tangle score, Braak neurofibrillary stage, CERAD neuritic plaque density, MMSE score and apolipoprotein E – E4 gene dosage (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Higher magnification photomicrographs depicting diffuse and cored/neuritic plaques in the putamen of a subject with a clinicopathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The section shown in A was stained with Thioflavine S while that in B was stained with the Campbell-Switzer silver stain. Gray arrows indicate diffuse plaques and white arrows indicate neuritic/cored plaques.

Table 3.

Correlations (Spearman) of striatal total plaque score with other measures of AD histopathology, cognitive function (MMSE) and apolipoprotein E – E4 gene dosage (0 = no E4 allele, 1 = 1 E4 allele, 2 = 2 E4 alleles). All correlations involved all subjects and were significant with p < 0.0001.

| Cortical Total Plaque Score | Cortical CERAD Neuritic Plaque Density | Cortical Total Tangle Score | Braak Neurofibrillary Stage | MMSE | ApoE–E4 Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.72 | − 0.63 | 0.40 |

A higher striatal total plaque density score (moderate or frequent) predicted a higher Braak NFT stage (Braak V or VI) with 95.8% sensitivity and 75.7% specificity (Table 4). A higher striatal total plaque density score (moderate or frequent) predicted the presence of dementia and clinicopathological AD (dementia with an intermediate or high NIA-Reagan rating) with 85.6% sensitivity and 86.2% sensitivity (Table 6). Making the criteria for striatal plaque density more permissive or more restrictive, or restricting criteria to the presence or absence of only the neuritic or cored plaque types (Tables 5 and 7), resulted in less overall predictive accuracy.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of a higher total striatal plaque score (moderate or frequent) for predicting a higher Braak neurofibrillary stage (V or VI). Values in each cell are the number of subjects. The sensitivity is 95.8% while the specificity is 75.7%.

| Braak Stage V or VI N = 91 |

Braak Stage 0 – IV N = 120 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Striatal Total Plaques Moderate or Frequent N = 116 |

89 | 27 |

|

Striatal Total Plaques Zero or Sparse N = 95 |

4 | 91 |

Table 6.

Sensitivity and specificity of a higher total striatal plaque score (moderate or frequent) for predicting clinicopathological AD (dementia with NIA-Reagan rating of intermediate or high). Values in each cell are the number of subjects. The sensitivity is 85.6% while the specificity is 86.2%.

| Clinicopathological AD N = 124 |

Not Clinicopathological AD N = 87 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Striatal Total Plaques Moderate or Frequent N =116 |

106 | 10 |

|

Striatal Total Plaques Zero or Sparse N = 95 |

18 | 77 |

Table 5.

Sensitivity and specificity of the presence or absence of neuritic/cored striatal plaques for predicting a higher Braak neurofibrillary stage (V or VI). Values in each cell are the number of subjects. The sensitivity is 90.1% while the specificity is 70.0%.

| Braak Stage V or VI N = 91 |

Braak Stage 0 – IV N = 120 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Striatal Neuritic/Cored Plaques Present N = 118 |

82 | 36 |

|

Striatal Neuritic/Cored Plaques Absent N = 93 |

9 | 84 |

Table 7.

Sensitivity and specificity of the presence or absence of striatal cored/neuritic plaques for predicting clinicopathological AD (dementia with NIA-Reagan rating of intermediate or high). Values in each cell are the number of subjects. The sensitivity is 80.6% while the specificity is 71.0%.

| Clinicopathological AD N = 124 |

Not Clinicopathological AD N = 87 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Striatal Cored/Neuritic Plaques Present N =118 |

100 | 18 |

|

Striatal Total Plaques Absent N = 93 |

24 | 69 |

Discussion

Recent amyloid imaging results [1–6] have confirmed longstanding neuropathological reports [7–19] that many non-demented elderly individuals have cortical amyloid plaques. It seems increasingly likely that non-demented subjects with cortical amyloid plaques represent a preclinical stage of AD, as cortical plaque density within these subjects correlates significantly with some measures of decreased cognition [1,3,49,50]. Additionally, non-demented subjects with plaques possess other characteristics of AD, including a cortical cholinergic deficit and a higher carriage rate of the apolipoprotein E – E4 allele [8,10]. Amyloid imaging therefore may provide a means to identify, for the purposes of recruitment for AD prevention clinical trials, non-demented subjects who are at increased risk for the development of dementia.

As a diagnostic method for AD, however, amyloid imaging is critically limited by a relatively poor correlation between cerebral cortex amyloid plaques and dementia. Currently, the clinical diagnosis of AD requires the presence of dementia [51]. Amyloid imaging does not indicate the extent of NFT spread throughout the brain and this also limits its usefulness, as the autopsy diagnosis of AD is based on the presence of dementia as well as a minimal brain load of both plaques and tangles [20].

Autopsy studies with limited clinical correlative data have suggested the amount of striatal amyloid deposition might be a useful marker of the presence of clinicopathological AD as striatal plaques occur only at later histopathological stages of AD, and largely after dementia onset [28,29]. In this study, we have confirmed this impression with a much larger sample size, as the results of our study of 211 subjects have shown a higher striatal total plaque density score (moderate or frequent) predicted a higher Braak NFT stage (Braak V or VI) with 95.8% sensitivity and 75.7% specificity. Additionally, a higher striatal total plaque density score (moderate or frequent) predicted the presence of clinicopathological AD with 85.6% sensitivity and 86.2% specificity. Restricting striatal plaque measures to include only neuritic and cored plaques did not increase the diagnostic accuracy. It is probable that amyloid imaging readily detects diffuse as well as cored and neuritic plaques [52,53] and therefore the diagnostic accuracy estimates presented here for total striatal plaques are probably more appropriate for extrapolation to the clinical situation.

In conclusion, amyloid imaging of the cerebral cortex and striatum together may allow for the clinical diagnosis of AD. Validation of this hypothesis will require large autopsy studies of subjects that had amyloid imaging during life.

Acknowledgments

The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

References

- 1.Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Darby D, Maruff P, Savage G, Ng S, Ackermann U, Cowie TF, Currie J, Chan SG, Jones G, Tochon-Danguy H, O’Keefe G, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Abeta deposits in older non-demented individuals with cognitive decline are indicative of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1688–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, Bandy D, Yu M, Lee W, Ayutyanont N, Keppler J, Reeder SA, Langbaum JB, Alexander GE, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Aizenstein HJ, DeKosky ST, Caselli RJ. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6820–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pike KE, Savage G, Villemagne VL, Ng S, Moss SA, Maruff P, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:2837–2844. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:446–452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mormino EC, Kluth JT, Madison CM, Rabinovici GD, Baker SL, Miller BL, Koeppe RA, Mathis CA, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Episodic memory loss is related to hippocampal-mediated beta-amyloid deposition in elderly subjects. Brain. 2009;132:1310–1323. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark CM, Schneider JA, Bedell BJ, Beach TG, Bilker WB, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Hefti F, Carpenter AP, Flitter ML, Krautkramer MJ, Kung HF, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Reiman EP, Zehntner SP, Skovronsky DM. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA. 2011;305:275–283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Buckles VD, Roe CM, Xiong C, Grundman M, Hansen LA, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Smith CD, Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Markesbery WR, Kaye J, Kurlan R, Hulette C, Kurland BF, Higdon R, Kukull W, Morris JC. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caselli RJ, Walker D, Sue L, Sabbagh M, Beach T. Amyloid load in nondemented brains correlates with APOE e4. Neurosci Lett. 2010;473:168–171. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beach TG, Kuo YM, Spiegel K, Emmerling MR, Sue LI, Kokjohn K, Roher AE. The cholinergic deficit coincides with Abeta deposition at the earliest histopathologic stages of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:308–313. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter PE, Rauschkolb PK, Pandya Y, Sue LI, Sabbagh MN, Walker DG, Beach TG. Pre-and post-synaptic cortical cholinergic deficits are proportional to amyloid plaque presence and density at preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0831-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beach TG, Honer WG, Hughes LH. Cholinergic fibre loss associated with diffuse plaques in the non- demented elderly: the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease? Acta Neuropathol(Berl) 1997;93:146–153. doi: 10.1007/s004010050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Sliwinski MJ, Lipton RB, Grober E, Marks-Nelson H, Antis P. Pathological markers associated with normal aging and dementia in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:566–573. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson DW, Crystal HA, Mattiace LA, Masur DM, Blau AD, Davies P, Yen SH, Aronson MK. Identification of normal and pathological aging in prospectively studied nondemented elderly humans. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:179–189. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90027-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouras C, Hof PR, Giannakopoulos P, Michel JP, Morrison JH. Regional distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in the cerebral cortex of elderly patients: a quantitative evaluation of a one-year autopsy population from a geriatric hospital. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:138–150. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitt FA, Davis DG, Wekstein DR, Smith CD, Ashford JW, Markesbery WR. “Preclinical” AD revisited: neuropathology of cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2000;55:370–376. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies L, Wolska B, Hilbich C, Multhaup G, Martins R, Simms G, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. A4 amyloid protein deposition and the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence in aged brains determined by immunocytochemistry compared with conventional neuropathologic techniques. Neurology. 1988;38:1688–1693. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.11.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Arnold SE. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:378–84. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudelli RD, Ambler MW, Wisniewski HM. Morphology and distribution of Alzheimer neuritic (senile) and amyloid plaques in striatum and diencephalon. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;64:273–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00690393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bugiani O, Giaccone G, Frangione B, Ghetti B, Tagliavini F. Alzheimer patients: preamyloid deposits are more widely distributed than senile plaques throughout the central nervous system. Neurosci Lett. 1989;103:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brilliant MJ, Elble RJ, Ghobrial M, Struble RG. The distribution of amyloid beta protein deposition in the corpus striatum of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1997;23:322–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suenaga T, Hirano A, Llena JF, Yen SH, Dickson DW. Modified Bielschowsky stain and immunohistochemical studies on striatal plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;80:280–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00294646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selden N, Mesulam MM, Geula C. Human striatum: the distribution of neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1994;648:327–331. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakabayashi J, Yoshimura M, Morishima-Kawashima M, Funato H, Miyakawa T, Yamazaki T, Ihara Y. Amyloid beta-protein (A beta) accumulation in the putamen and mammillary body during aging and in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:343–352. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwatsubo T, Saido TC, Mann DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Full-length amyloid-beta (1-42(43)) and amino-terminally modified and truncated amyloid-beta 42(43) deposit in diffuse plaques. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1823–1830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–1800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braak H, Braak E. Alzheimer’s disease: striatal amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1990;49:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf DS, Gearing M, Snowdon DA, Mori H, Markesbery WR, Mirra SS. Progression of regional neuropathology in Alzheimer disease and normal elderly: findings from the Nun study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:226–231. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuboi Y, Uchikado H, Dickson DW. Neuropathology of Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies with reference to striatal pathology. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl 3):S221–S224. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalaitzakis ME, Walls AJ, Pearce RK, Gentleman SM. Striatal Abeta peptide deposition mirrors dementia and differentiates DLB and PDD from other Parkinsonian syndromes. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalaitzakis ME, Graeber MB, Gentleman SM, Pearce RK. Striatal beta-amyloid deposition in Parkinson disease with dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:155–161. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31816362aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klunk WE, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko SK, Bi W, Hoge JA, Cohen AD, Ikonomovic MD, Saxton JA, Snitz BE, Pollen DA, Moonis M, Lippa CF, Swearer JM, Johnson KA, Rentz DM, Fischman AJ, Aizenstein HJ, DeKosky ST. Amyloid deposition begins in the striatum of presenilin-1 mutation carriers from two unrelated pedigrees. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6174–6184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koivunen J, Verkkoniemi A, Aalto S, Paetau A, Ahonen JP, Viitanen M, Nagren K, Rokka J, Haaparanta M, Kalimo H, Rinne JO. PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake shows predominantly striatal increase in variant Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:1845–1853. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villemagne VL, Ataka S, Mizuno T, Brooks WS, Wada Y, Kondo M, Jones G, Watanabe Y, Mulligan R, Nakagawa M, Miki T, Shimada H, O’Keefe GJ, Masters CL, Mori H, Rowe CC. High striatal amyloid beta-peptide deposition across different autosomal Alzheimer disease mutation types. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1537–1544. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ringman JM, Gylys KH, Medina LD, Fox M, Kepe V, Flores DL, Apostolova LG, Barrio JR, Small G, Silverman DH, Siu E, Cederbaum S, Hecimovic S, Malnar M, Chakraverty S, Goate AM, Bird TD. Biochemical, neuropathological, and neuroimaging characteristics of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease due to a novel PSEN1 mutation. Neurosci Lett. 2011;487:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raji CA, Becker JT, Tsopelas ND, Price JC, Mathis CA, Saxton JA, Lopresti BJ, Hoge JA, Ziolko SK, DeKosky ST, Klunk WE. Characterizing regional correlation, laterality and symmetry of amyloid deposition in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound B. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;172:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergstrom M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausen B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Langstrom B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, Alkalay A, Racine CA, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Baker SL, Agarwal N, Bonasera SJ, Mormino EC, Weiner MW, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ. Increased metabolic vulnerability in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is not related to amyloid burden. Brain. 2010;133:512–528. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Roher AE, Lue L, Vedders L, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Rogers J. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9:229–245. doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braak H, Braak E. Demonstration of amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary changes in whole brain sections. Brain Pathol. 1991;1:213–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1991.tb00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol(Berl) 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi SR, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Zehntner SP, Krautkramer M, Kung HF, Skovronsky DM, Hefti F, Clark CM. Correlation of amyloid PET ligand florbetapir F 18 (18F-AV-45) binding with β-amyloid aggregation and neuritic plaque deposition in postmortem brain tissue. 2011 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31821300bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, Amaducci L, Orgogozo JM, Brun A, Hofman A. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del ST, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beach TG, Sue L, Scott S, Layne K, Newell A, Walker D, Baker M, Sahara N, Yen SH, Hutton M, Caselli R, Adler C, Connor D, Sabbagh M. Hippocampal sclerosis dementia with tauopathy. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:263–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hatashita S, Yamasaki H. Clinically different stages of Alzheimer’s disease associated by amyloid deposition with [11C]-PIB PET imaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:995–1003. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson PW, Ye L, Morgenstern JL, Sue L, Beach TG, Judd DJ, Shipley NJ, Libri V, Lockhart A. Interaction of the amyloid imaging tracer FDDNP with hallmark Alzheimer’s disease pathologies. J Neurochem. 2009;109:623–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lockhart A, Lamb JR, Osredkar T, Sue LI, Joyce JN, Ye L, Libri V, Leppert D, Beach TG. PIB is a non-specific imaging marker of amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide-related cerebral amyloidosis. Brain. 2007;130:2607–15. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]